-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Hydraulic Engineering

p-ISSN: 2169-9771 e-ISSN: 2169-9801

2025; 13(1): 17-30

doi:10.5923/j.ijhe.20251301.02

Received: Oct. 9, 2025; Accepted: Oct. 29, 2025; Published: Nov. 7, 2025

Adjusting DualSPHysics, a Smoothed Particles Hydrodynamics Model, to Match Laboratory Experiment Data of Non-Newtonian Carbopol Gel Solution

Andrei Chadanowicz1, Yuri Taglieri Sáo2, Tobias Bernward Bleninger3, Geraldo de Freitas Maciel4

1Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia Ambiental, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, R. XV de Novembro 1299, Brazil

2Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia Mecânica, Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, São Paulo, Rua dos Patriotas 315, Brazil

3Departmento de Engenharia Ambiental, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, R. XV de Novembro 1299, Brazil

4Departmento de Engenharia Civil, Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, São Paulo, Rua dos Patriotas 315, Brazil

Correspondence to: Andrei Chadanowicz, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia Ambiental, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, R. XV de Novembro 1299, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

DualSPHysics is a software that employs the Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) method to model fluids by discretizing the fluid domain into a finite number of particles. In this work, we attempt to calibrate the software's settings to simulate a non-Newtonian flow, a type of fluid that exhibits non-linear deformation behavior, while working with a three-dimensional simulation and boundary particles that simulate a steadily rising dam. By fitting a rheological model that describes the behavior of non-Newtonian fluids and systematically combining different settings, we aim to adjust the DualSPHysics model to match experimental data from a Carbopol gel dam-break scenario. Each setting is compared by calculating the relative error to the experimental data, and the best fit is determined based on the lowest relative error. The final simulation results partly diverge from the experimental data since the dam's boundary particles' influence is significant during the early stages of the dam-break simulation.

Keywords: Smoothed particles hydrodynamics, Non-Newtonian fluid, Dam break

Cite this paper: Andrei Chadanowicz, Yuri Taglieri Sáo, Tobias Bernward Bleninger, Geraldo de Freitas Maciel, Adjusting DualSPHysics, a Smoothed Particles Hydrodynamics Model, to Match Laboratory Experiment Data of Non-Newtonian Carbopol Gel Solution, International Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2025, pp. 17-30. doi: 10.5923/j.ijhe.20251301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- As the global population continues to grow, the demand for resources and living spaces escalates accordingly. One critical aspect of resource extraction involves mining facilities, which employ dams to contain the waste generated during the extraction process. This waste material, known as tailings, is composed primarily of fine grains, such as clay, silt and fine sand [1,2]. Tailings are generally transported in liquefied form to the tailing dams through pipeline systems [3]. However, the rheological nature of liquefied mining tailings deviates from the behavior of Newtonian fluids, such as water and oil, being considered a non-Newtonian fluid [4,5]. The study of rheological properties of tailings and their flow plays a vital role in establishing safety protocols and in determining flooded areas for mining waste dams through a tailings dambreak analysis [6]. This analysis is usually carried out with numerical models, which require rheological properties of the flowing material as input parameters. Thus, by investigating the rheological properties of these materials, researchers can establish effective measures to ensure the safety of people living around mining waste dams.Nevertheless, the study of non-Newtonian fluid flows is a non-trivial challenge, since non-Newtonian rheological models are often more complex than the standard Newtonian model. If the classical Newtonian fluid mechanics theory provides only a few analytical solutions, the non-Newtonian theory provides even less. With the advance of computational power, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) poses itself as a field that facilitates the study of non-Newtonian flows by simulating the behavior of fluids through computational means. By applying numerical methods and algorithms, CFD offers a powerful tool to model and analyze the intricate dynamics of fluids, including the non-Newtonian fluids.When simulating non-Newtonian fluids, computational dynamics software frequently relies on either the finite difference method or the finite volume method to solve the governing partial differential equations, that ensure a balance of flux, mass, and momentum across the boundaries of discretized control volumes. Noteworthy software used for non-Newtonian fluid simulation includes, for instance, FLO-2D/3D, HEC-RAS, Riverflow2D, DHI MIKE 21/3, FLOW3D, and DAN3D [7].Within the domain of CFD, Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) has emerged as a paradigm-shifting approach. In contrast to conventional grid-based methods, SPH employs a particle-based framework fit to simulate problems with a complex frontier dynamic. The fundamental principle of SPH revolves around discretising the fluid domain into discrete particles, each with properties like mass, position, and velocity. Interactions between pairs of particles inside smoothing kernels are calculated using hydrodynamics equations that dictate fluid behaviours.One of the key advantages of SPH lies in its ability to handle fluid flows with high deformability, complex boundaries and free surfaces [8], meanwhile, the treatment of boundary conditions is certainly one of the difficult technical points of the method. The particle-based nature of SPH allows for easier free surface fluid scenarios and handling of multiphase interactions [9], making it well-suited for simulating scenarios such as liquid sloshing [10], dam break simulations, and ocean waves [11]. It also works well with complex and moving boundaries, which are notably difficult to simulate using mesh-based simulations [12].DualSPHysics was already used to simulate classic dambreak scenarios of non-newtonian fluids and compared to experimental data. A work with non-Newtonian SPH and a real-life dam break scenario was done using an incompressible SPH formulation and achieved good agreement between numerical simulations and available experimental data [13]. Another work with non-Newtonian SPH simulations used a weakly-compressible formulation to achieve numerical results that closely agree with experimental data [14]. These studies exemplify the effectiveness of SPH in capturing the complexities of non-Newtonian fluid dynamics during dam-break events.However, both of the previously mentioned articles worked with two dimensional simulations of instantaneously released fluid. Studies are missing where three-dimensional unsteady flows are investigated, where the dam break event (breaching) occurs over a certain time period. We overcome that gap by working with a three dimensional simulation, and considering an experiment where a vertical plate represented the dam, which is removed at known speed. Thus, we are taking into account the speed at which the dam rises to mirror experimental conditions. Our hypothesis is that the moving dam boundary could prove to have big influences on the way the fluid behaves throughout the simulations.Furthermore, as with most numerical approaches, implementing an SPH model to simulate non-Newtonian fluids requires a calibration process to ensure that the simulated behavior accurately reproduces the physical phenomenon of interest. This process involves defining target data that represents the expected model outputs and identifying the parameters to be adjusted. In many cases, calibration is conducted manually through a trial-and-error procedure, where parameters are iteratively tuned until the model results achieve satisfactory agreement with the reference data.For computationally efficient models, this process can be automated through optimization algorithms such as DSS, which iteratively execute simulations and adjust parameters to minimize discrepancies between simulated and target outcomes. When dealing with more computationally demanding models, however, such approaches become less practical due to the high simulation cost. In these cases, calibration must be approached more strategically, prioritizing simulations that maximize information gain while minimizing computational expense. Such parameter tuning studies are a necessary preliminary step in any computational simulation. However, even though existing for non SPH-based approaches, like Eulerian RANS (Reynolds averaged Navier-Stokes) solvers, such parameter studies have not been undertaken and published so far for SPH models. This knowledge gap will be handled in the presented manuscript, by identifying and evaluating suitable parameters within an SPH-based code with specific emphasis on non-Newtonian fluids, and a dam-break type application case.

1.1. Objectives

- The primary objective of this work is to demonstrate the application of the DualSPHysics model to an idealized dam-break scenario involving a non-Newtonian fluid, specifically carbopol gel. We aim to bridge the gap between experimental observations and computational simulations by comparing three-dimensional, unsteady flow SPH-generated results with available experimental data. Secondly we were tuning the model parameters to achieve a closer correspondence between simulation and experiment. The findings presented here are intended to guide future simulations by illustrating how individual parameters influence the behavior of non-Newtonian fluid flows and by highlighting the settings that most effectively reproduce the observed experimental behavior.

2. Rheological Aspects

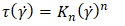

- Rheology can be understood as the science that studies the deformation and flow of materials. In order to characterize rheologically a material, a relationship between shear stress

and shear rate

and shear rate  is required, producing the flow curve. Several experimental techniques are used to determine the flow curve by exerting a known shear stress and measuring the shear rate, or vice-versa. Then, a rheological model is adjusted to the flow curve points and the corresponding rheological parameters are obtained. The simplest, one dimensional, model is the Newtonian model (equation 1), featuring a linear relationship between shear rate

is required, producing the flow curve. Several experimental techniques are used to determine the flow curve by exerting a known shear stress and measuring the shear rate, or vice-versa. Then, a rheological model is adjusted to the flow curve points and the corresponding rheological parameters are obtained. The simplest, one dimensional, model is the Newtonian model (equation 1), featuring a linear relationship between shear rate  and shear stress, usually denoted as the partial derivative of velocity with respect to a perpendicular direction

and shear stress, usually denoted as the partial derivative of velocity with respect to a perpendicular direction  , and connected by dynamic viscosity

, and connected by dynamic viscosity  .

. | (1) |

| (2) |

denotes the second-order shear rate tensor and

denotes the second-order shear rate tensor and  is the second-order strain rate tensor.Non-Newtonian fluids, however, exhibit a non-linear relationship between shear rate and shear stress. Consequently, a different approach is required compared to the treatment of absolute viscosity. This is where apparent viscosity

is the second-order strain rate tensor.Non-Newtonian fluids, however, exhibit a non-linear relationship between shear rate and shear stress. Consequently, a different approach is required compared to the treatment of absolute viscosity. This is where apparent viscosity  becomes useful. It is defined as the ratio of shear stress

becomes useful. It is defined as the ratio of shear stress  to shear rate

to shear rate  , as expressed in equation 3.

, as expressed in equation 3. | (3) |

is dependent on the strain rate tensor (D) in a non- linear manner, which implies that the viscosity is a function of the shear rate. The strain rate tensor, also referred to as the rate of deformation tensor, describes the rate at which fluid elements deform.

is dependent on the strain rate tensor (D) in a non- linear manner, which implies that the viscosity is a function of the shear rate. The strain rate tensor, also referred to as the rate of deformation tensor, describes the rate at which fluid elements deform. | (4) |

is a characteristic stress parameter that represents the stress contribution in the first term of the model. The term

is a characteristic stress parameter that represents the stress contribution in the first term of the model. The term  denotes the second invariant of the strain rate tensor.The power-law model, for example:

denotes the second invariant of the strain rate tensor.The power-law model, for example: | (5) |

| (6) |

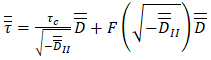

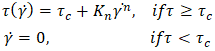

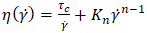

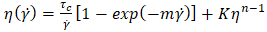

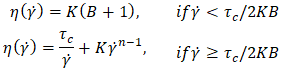

.In the context of liquefied mining tailings, these materials are commonly described as viscoplastic fluids, or yield stress fluids [15]. They require a certain amount of stress, known as the yield stress (τc), to start deforming. For an applied shear stress below the yield stress, the fluid behaves as a solid material, resisting deformation. Once the yield stress is overcome, flow starts, and the fluid exhibits liquid behavior. A more general rheological model, the Herschel-Bulkley model [16], captures both shear-thinning (or dilatancy) and viscoplasticity, as shown in Equation 7:

.In the context of liquefied mining tailings, these materials are commonly described as viscoplastic fluids, or yield stress fluids [15]. They require a certain amount of stress, known as the yield stress (τc), to start deforming. For an applied shear stress below the yield stress, the fluid behaves as a solid material, resisting deformation. Once the yield stress is overcome, flow starts, and the fluid exhibits liquid behavior. A more general rheological model, the Herschel-Bulkley model [16], captures both shear-thinning (or dilatancy) and viscoplasticity, as shown in Equation 7: | (7) |

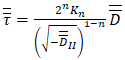

. If

. If  and

and the Bingham model is obtained, which is commonly employed to describe liquefied tailings [3]. As the DualSPHysics code utilizes rheological equations in a one-dimensional format, this and subsequent equations are exclusively expressed in a one-dimensional manner.The application of rheological models in CFD relies on including them at the viscous term of the governing momentum equations. Equation 8 shows the Herschel-Bulkley model in terms of apparent viscosity η, by dividing Equation 7 by

the Bingham model is obtained, which is commonly employed to describe liquefied tailings [3]. As the DualSPHysics code utilizes rheological equations in a one-dimensional format, this and subsequent equations are exclusively expressed in a one-dimensional manner.The application of rheological models in CFD relies on including them at the viscous term of the governing momentum equations. Equation 8 shows the Herschel-Bulkley model in terms of apparent viscosity η, by dividing Equation 7 by  .

. | (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

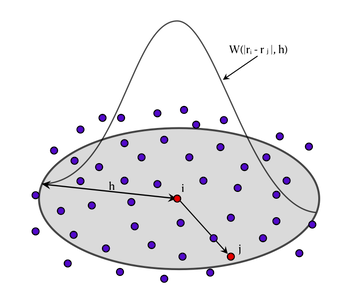

3. SPH Background and Formulation

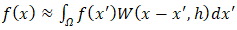

- The Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) method was originally introduced by Gingold & Monaghan in 1977 as a computational technique for simulating astronomical phenomena. It’s formulated (equation 11) as the convolution of a function

and a kernel function,

and a kernel function,  , with h being the smoothing length of the kernel function, on a point x over an

, with h being the smoothing length of the kernel function, on a point x over an  domain [19]. The kernel function plays a crucial role in SPH by approximating the behavior of a Dirac delta function, facilitating the smooth spread of properties and interactions between neighbouring particles.

domain [19]. The kernel function plays a crucial role in SPH by approximating the behavior of a Dirac delta function, facilitating the smooth spread of properties and interactions between neighbouring particles. | (11) |

| (12) |

| Figure 1. SPH particles and Smoothing Kernel Representation |

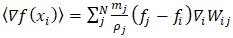

as

as  meaning the value of the kernel function between the two particles and considering the volume

meaning the value of the kernel function between the two particles and considering the volume  as the ratio between the mass

as the ratio between the mass  and the density

and the density  of the particle j, we can rewrite the SPH interpolation as:

of the particle j, we can rewrite the SPH interpolation as:  | (13) |

4. Methodology

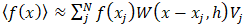

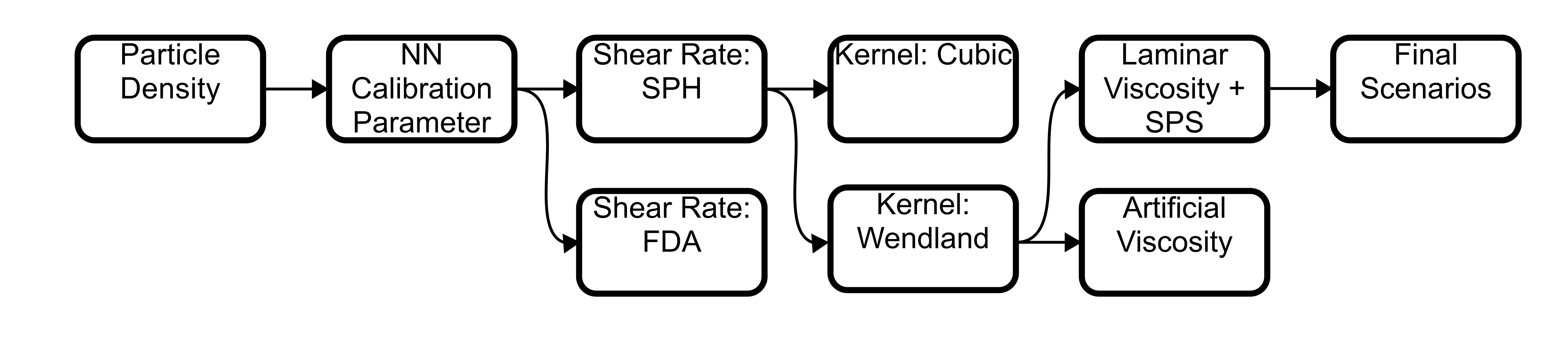

- The SPH DualSPHysics model was employed to simulate a scenario akin to experiments conducted on non-Newtonian Carbopol gel [22]. Various configurations of the DualSPHysics model were evaluated to determine the optimal setup for achieving improved accuracy in comparison to experimental data.While applying the DualSPHysics model, its effectiveness hinges not only on choosing the right parameters but also ensuring its fine-tuning through calibration. This relationship between parameter sensitivity and model fit determines the accuracy with which the simulation mirrors experimental data. In this study, we delve into the process of calibration, aiming to optimize parameters and elevate the model’s fidelity to real-world observations.However, not all settings prove equally effective. Through this work, we identify and separate configurations that do not yield satisfactory results. This preliminary step is crucial before comparing various combinations of settings that result in more subtle differences between each other, ensuring a more concise analysis. The configurations tested and compared in this work are shown in the flowchart (Figure 2). The ones that were shown to be worse are not taken through to the final scenarios tested.

| Figure 2. Flowchart of the Scenarios Simulated Throughout this work |

4.1. Experimental Scenario

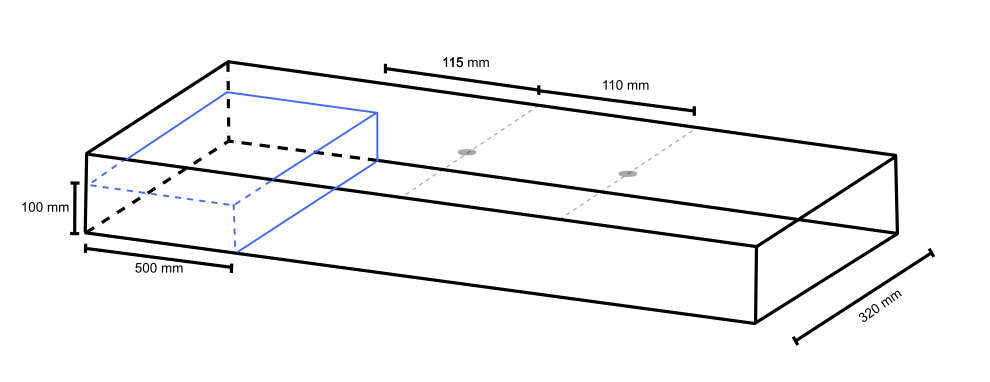

- A typical dambreak experiment was set up using Carbopol gel and a camera to record how the fluid flows [22] (figure 3). The dam was represented by a vertical plate. The dam break was simulated by rising the plate at a steady rate to keep the velocity constant. The fluid’s reach was taken from the images recorded with the camera and applying the Canny Edge Detector algorithm [23]. Data compared was from a scenario with rising dam speed of 0.17 m/s. Two sensor were also mounted on top of the experiment to measure the fluid depth by measuring the distance from the sensor to the fluid. One sensor 615 mm from the back of the tank and the second 725 mm from the back. Initial setup parameters scheme can be seen in figure 4.

| Figure 3. Experimental Tank Initial Setup for Data Recording from [22] |

| Figure 4. Experiment and Simulation Starting Configuration and Dimensions |

, consistency

, consistency  and flow index (n) [24]. A gel solution of Carbopol 996 polymer with 0.17% mass was used. Its adjusted properties are density of 1000kg/m3 and rheological properties: 57.12 Pa shear yield stress, 15.35

and flow index (n) [24]. A gel solution of Carbopol 996 polymer with 0.17% mass was used. Its adjusted properties are density of 1000kg/m3 and rheological properties: 57.12 Pa shear yield stress, 15.35  consistency and 0.420 flow index.The non-Newtonian characteristics and parameters were incorporated into the DualSPHysics model. Meanwhile, the experimental geometry served as the model’s initial condition, providing a foundation for attempting to replicate the observed results.

consistency and 0.420 flow index.The non-Newtonian characteristics and parameters were incorporated into the DualSPHysics model. Meanwhile, the experimental geometry served as the model’s initial condition, providing a foundation for attempting to replicate the observed results.4.2. DualSPHysics

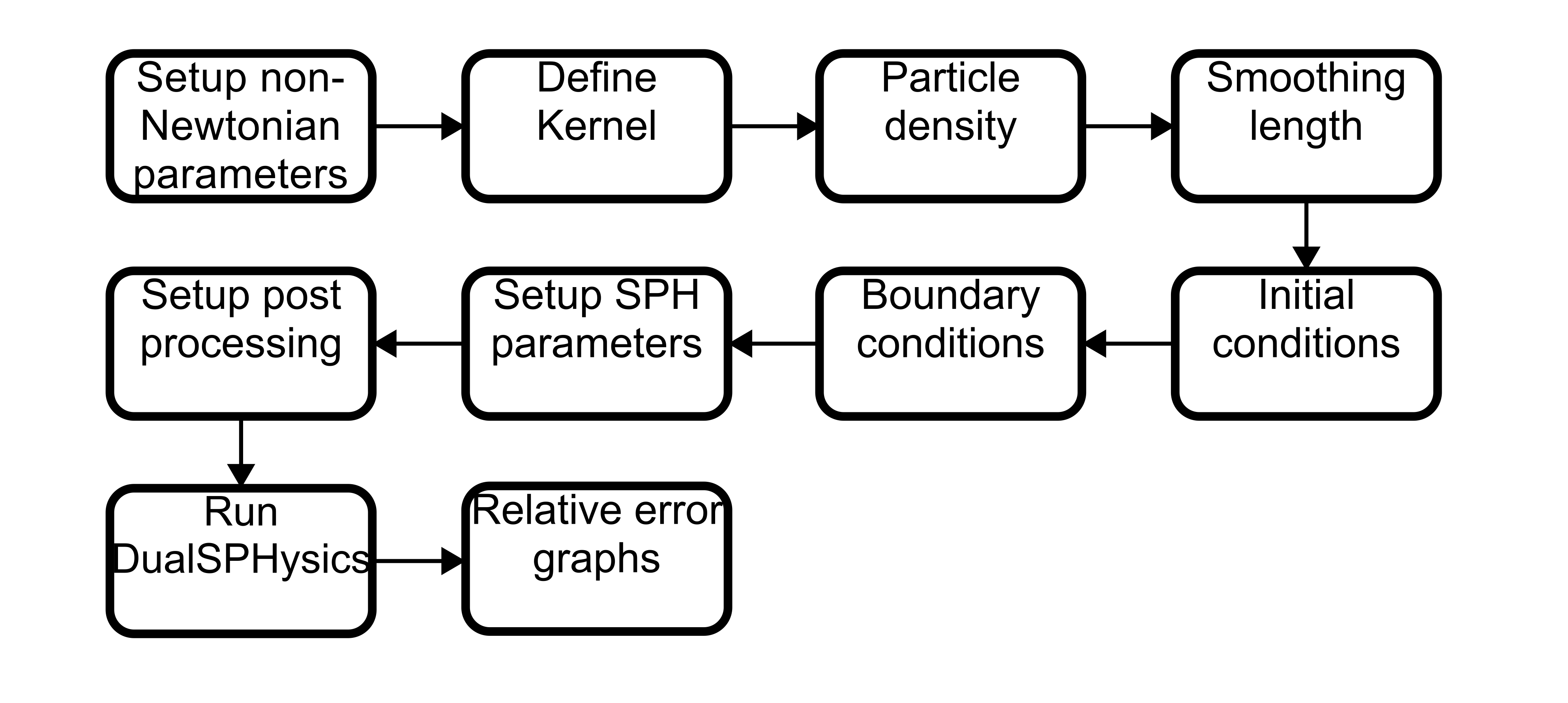

- This work was made using the open-source DualSPHysics model [25], which uses both the computer’s CPU and GPU for processing, making it more efficient and faster than a regular CPU implementation due to the architecture difference. The GPU implementation of SPH via CUDA benefits from the inherent centered and explicit nature of the formulation [26].CUDA serves as a powerful programming platform facilitating the utilization of a computer’s Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) for general-purpose computing. Harnessing the distinctive architecture of GPUs, it enables superior computing performance in tasks demanding a high level of parallelization. This stands in contrast to computations executed solely by the computer’s Central Processing Unit (CPU), as the GPU’s architecture excels in parallel processing [27].With this approach, the properties of each particle can be updated independently during each time step. This characteristic allows for efficient parallelization, enabling the simultaneous update of multiple particles as long as there is sufficient computational power available. By harnessing the capabilities of GPU processing, the SPH implementation becomes highly optimized, enhancing the speed and efficiency of the simulation [28].The model setup steps are outlined in the following flowchart (Figure 5). It’s important to note the sequence of setup steps, as the initial and boundary conditions depend on the smoothing length due to the potential gap formation between boundaries and fluid particles, which is further explained later. Post-processing is configured separately in DualSPHysics, as desired variables need to be calculated using the SPH summation formula (equation 12) for each desired position that isn’t occupied by a particle.

| Figure 5. Flowchart of the Setup Steps used for running DualSPHysics model |

4.3. Initial and Boundary Conditions

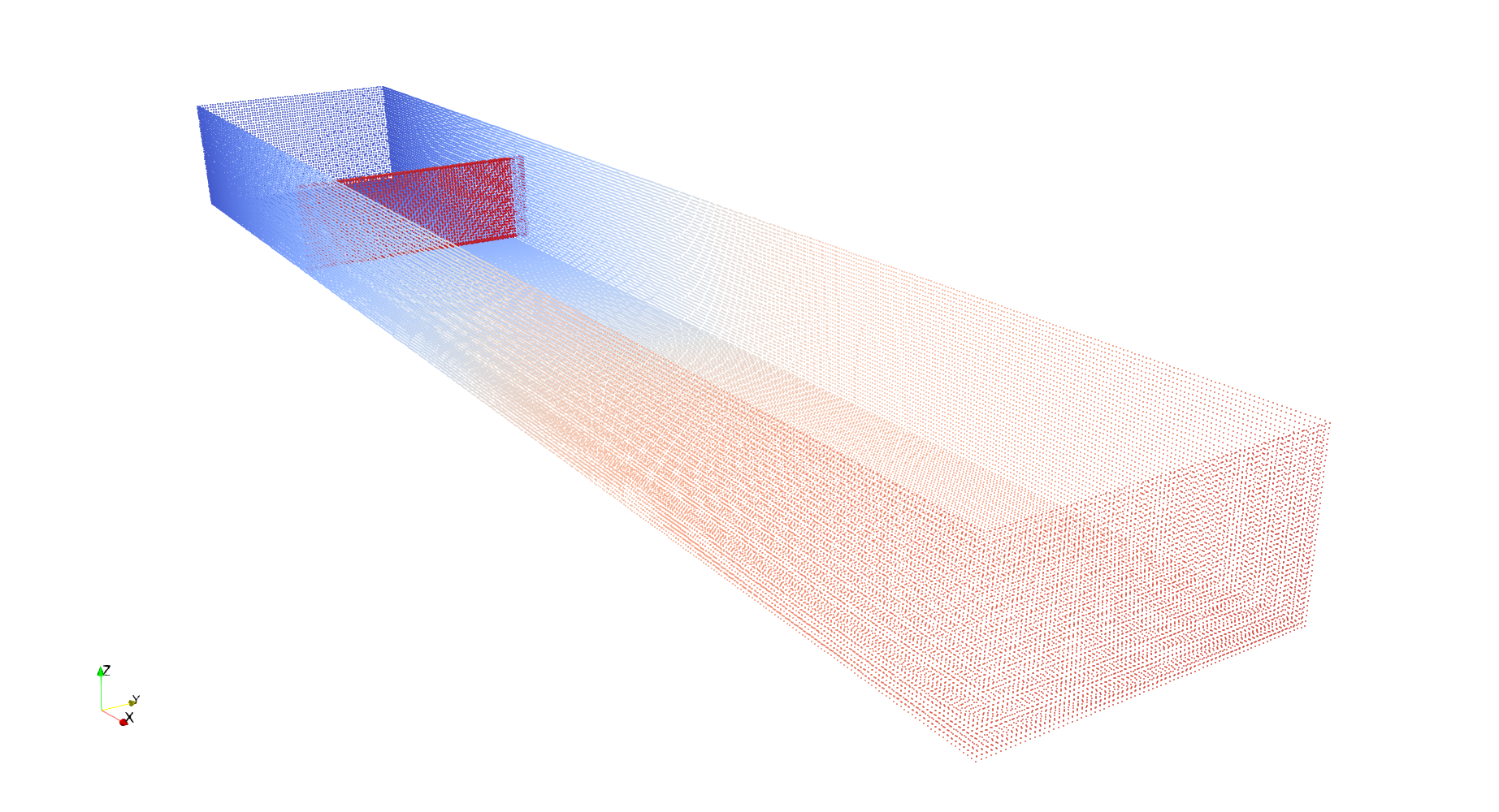

- As mentioned earlier, the initial conditions for the SPH model are configured based on the experiment’s geometry. The conversion of the experiment’s physical components, including walls and the fluid, into discrete particles is achieved by implementing SPH equations with an internal particle distance set at 0.004 m. The boundary particles and the rising dam can be seen in figure 6.

| Figure 6. Boundary Particles Used on the SPH Simulations |

4.4. Resolution and Particle Density

- When employing SPH, there’s no need for a grid that must be refined locally and tailored to the desired domain. Also, unlike traditional numerical methods like finite differences, SPH doesn’t follow the same convergence conditions. Therefore, determining the resolution must be approached differently.What is commonly employed to determine the particle density in SPH simulations is doubling the number of particles modelled until the results converge between two simulations [30,31]. This way ensures the particle number is no longer affecting the simulation by means of lack of particles or by a saturation of particles inside the smoothing length [32].The resolution employed in this work was of 0.004m between each particle, resulting in a total of 305,077 particles. While this resolution fits the previously mentioned criteria (half of this resolution wields the same results), it was chosen as to use all the computational power available, as our used machine couldn’t handle higher resolutions.The computer used for the simulations had an Intel i5 10th generation processor (model i5-10400F) with 16 gigabytes of available RAM and a NVIDIA GeForce GTX1650 with 4 gigabytes of dedicated GPU memory that was used for the simulations.

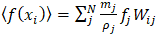

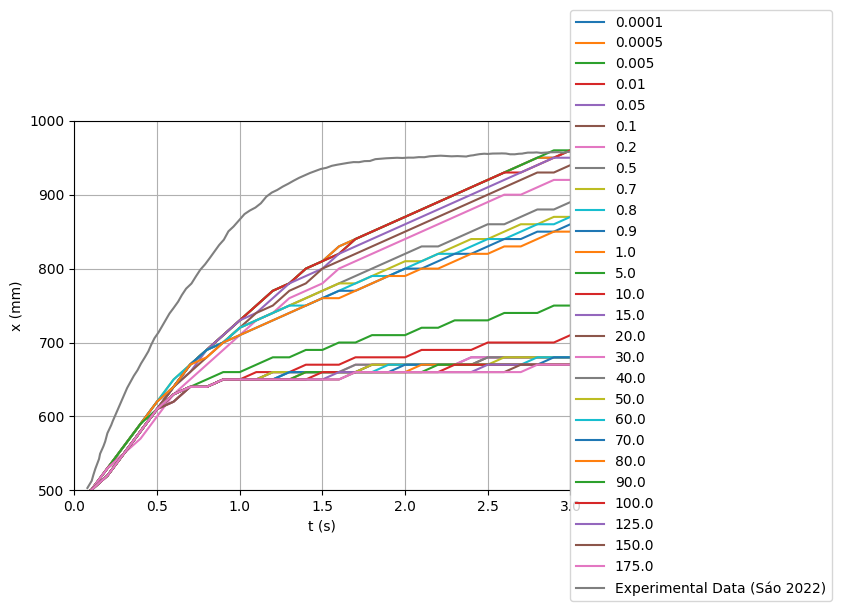

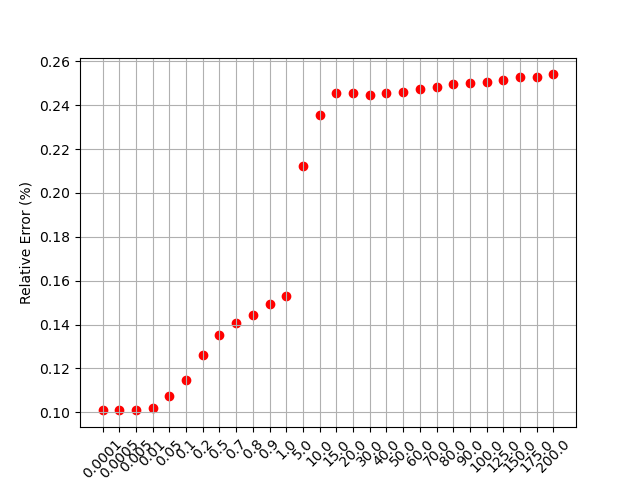

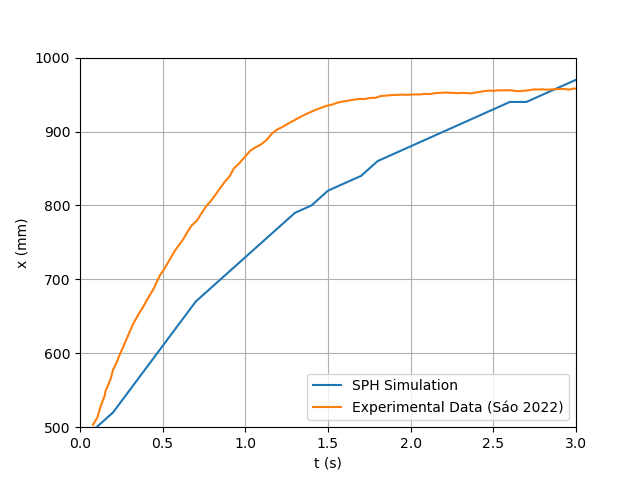

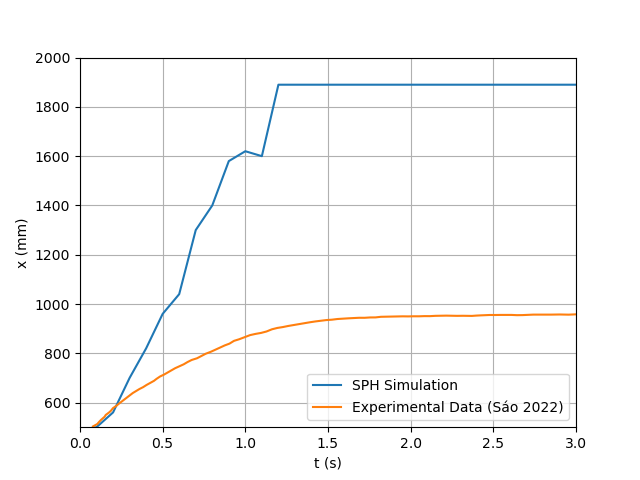

4.5. Bi-Viscous Calibration Parameter

- As mentioned earlier, the utilization of the bi-viscous formula involves a calibration parameter. To determine the optimal value for this parameter, a series of simulations were conducted, each employing different values for the calibration parameter. The average relative error was calculated for each calibration parameter simulation in order to find the lowest relative error. The objective was to discern which parameter value would most closely simulate the previous experimental outcomes.The outcomes of these simulations are visually represented in figure 7 showing the position of the head of the flood wave versus time. The best fit was chosen based on the lower average relative error in relation to the experimental data, the values for the average relative error are shown in figure 8. The value of B=0.005 exhibits a commendable level of agreement with the lowest average relative error of the other simulations of 10%. However, it is imperative to note that, particularly during the initial phases of the flow, the simulation does not entirely align with the experimental data.

| Figure 7. Simulation Results for the position of the head of the flood wave versus time for each tested non-Newtonian Calibration Parameter |

| Figure 8. Average Relative Error for Each Tested Calibration Parameter |

4.6. Shear Rate Calculation

- In DualSPHysics, shear rate can be calculated through two different ways. The first employs the conventional Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) formulation to obtain velocity derivatives. The second method involves an adaptation of Finite Differences (FDA), determined by the difference between the velocity of a particle and that of its neighboring particles.

4.6.1. SPH Calculation for Shear Rate

- A fundamental expression for calculating the derivative of a function within Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics [33], is given by:

| (14) |

| Figure 9. SPH Results for the Dambreak Wave front Reach Throughout the Simulation Using SPH Shear Rate Calculation |

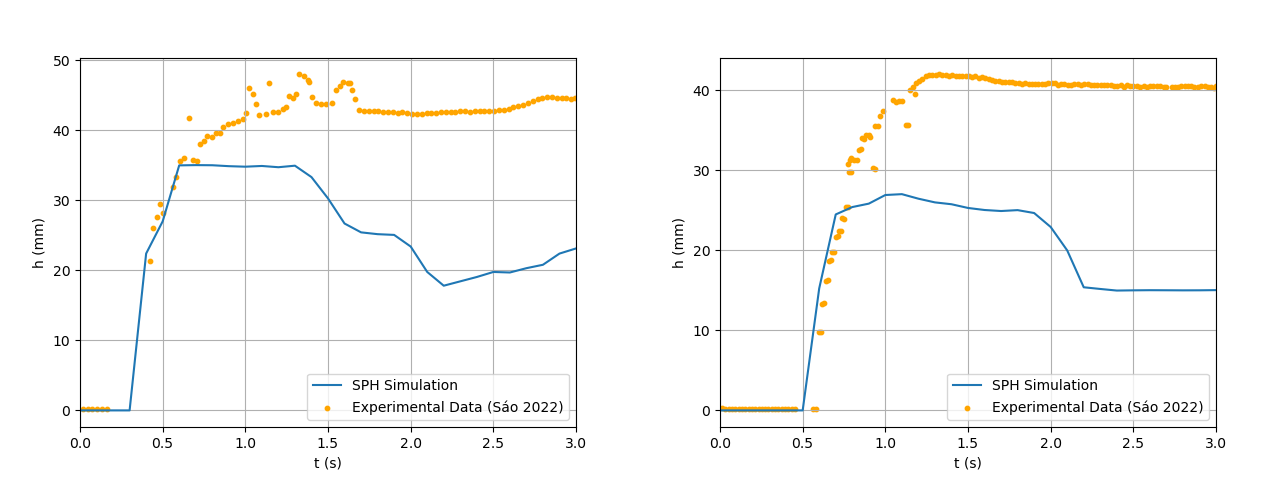

| Figure 10. Figure 10: SPH Results for Depth Below each Sensor (1 on the left and 2 on the right) Throughout the Simulation Using SPH ShearRate Calculation |

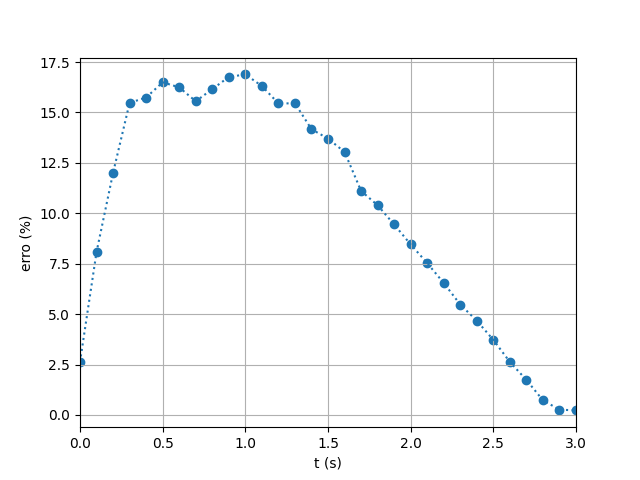

| Figure 11. Relative Error Throughout the Simulation for SPH Calculation of the Shear Rate |

4.6.2. SPH Calculation for Shear Rate

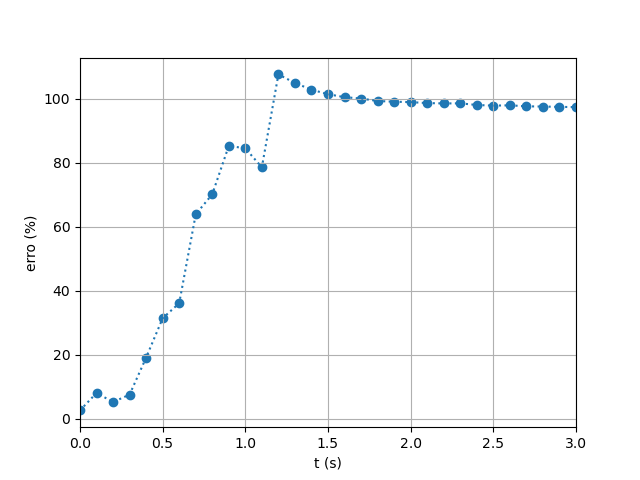

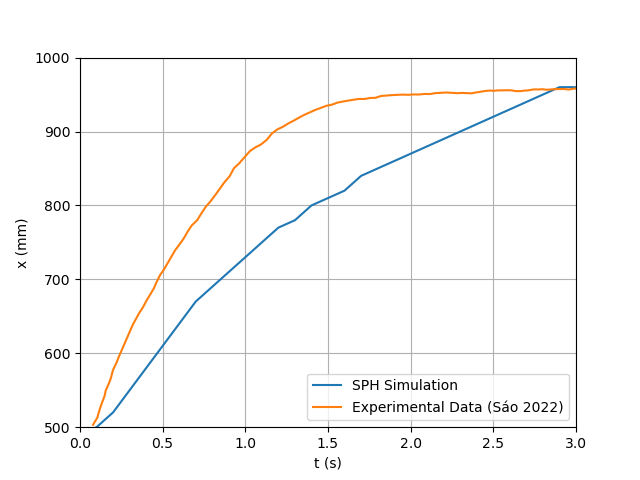

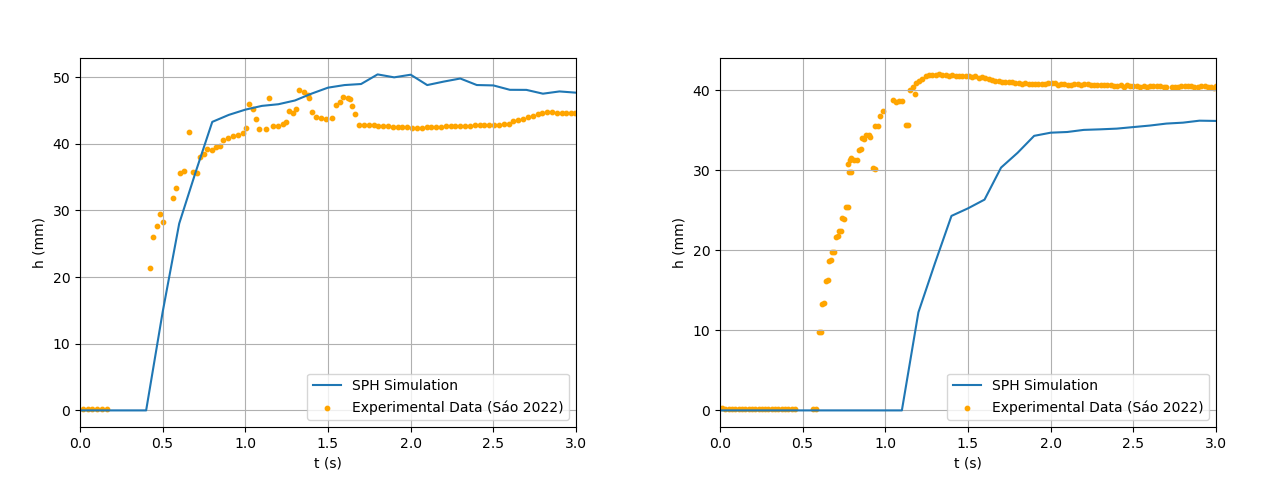

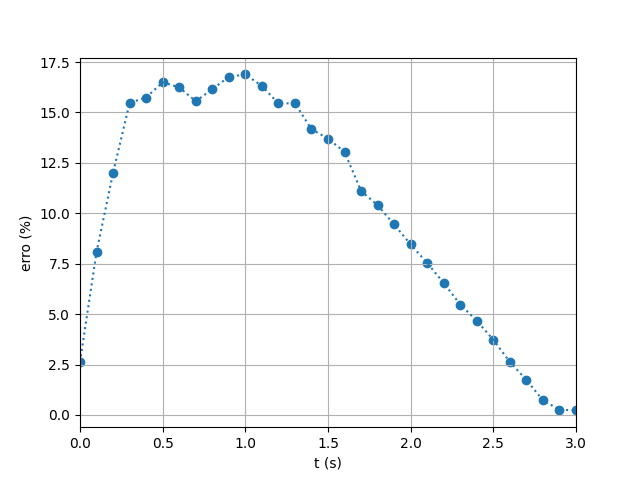

- In contrast to the SPH formulation, the FDA method employs finite differences between particles to compute shear rate. This approach is comparatively simpler to implement than the SPH method.Figures 12 and 13 show the simulated flow reach and depth beneath each sensor using the FDA approach. The corresponding relative errors (Figure 14) were considerably higher on average: 59% for the reach, and 36% and 44% for Sensors 1 and 2, respectively. These deviations suggest that the FDA method was unable to adequately reproduce the fluid’s rheological behavior, leading to poorer agreement with experimental data.

| Figure 12. SPH Results for the Dambreak Wave Reach Throughout the Simulation Using FDA Shear Rate Calculation |

| Figure 13. SPH Results for Depth Below each Sensor (1 on the left and 2 on the right) Throughout the Simulation Using FDA ShearRate Calculation |

| Figure 14. Relative Error Throughout the Simulation for FDA Calculation of the Shear Rate |

4.7. Kernel

- Selecting the most suitable kernel is crucial for an effective simulation. Polynomial expressions are often favored for their computational efficiency. In our comparison, we evaluate the performance of both cubic and quintic formulations, the former being developed by Monaghan & Lattanzio and the latter by Wendland.

4.7.1. Cubic Spline

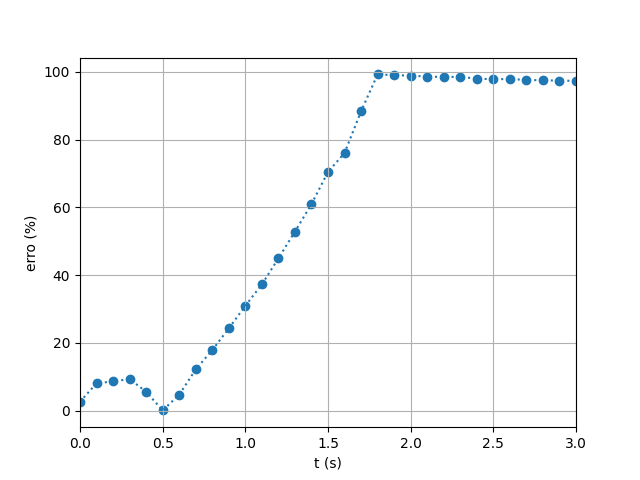

- The kernel cubic spline formulation [20] is expressed as:

| (15) |

denotes the distance between particles, and the coefficient

denotes the distance between particles, and the coefficient  is set to

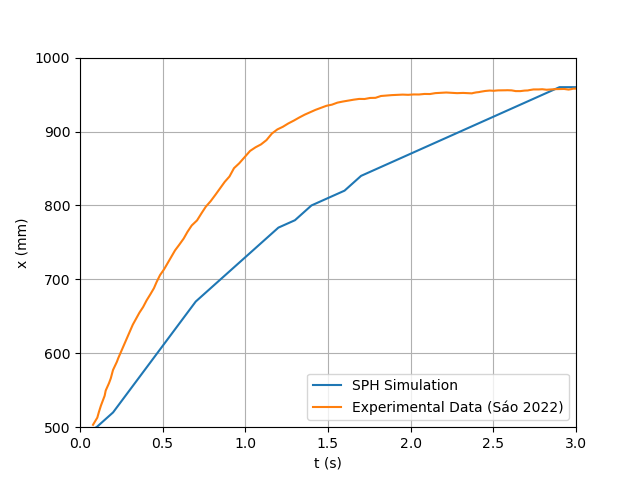

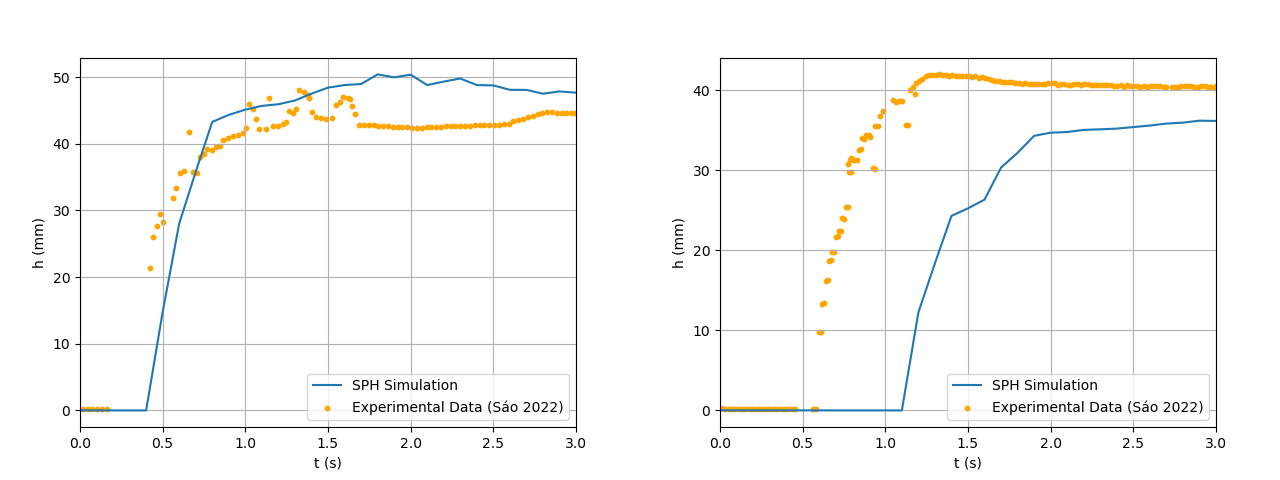

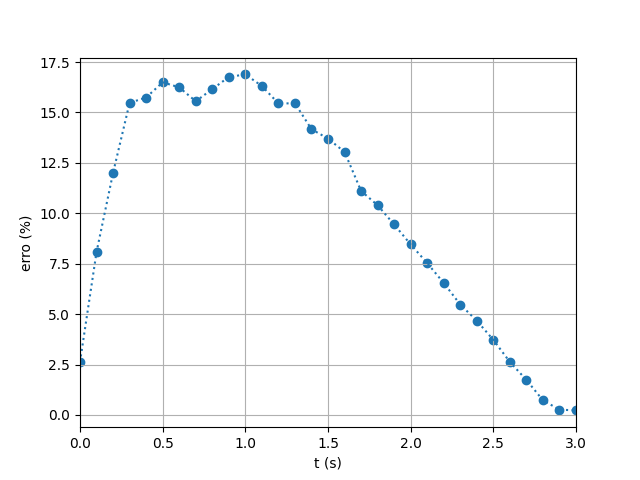

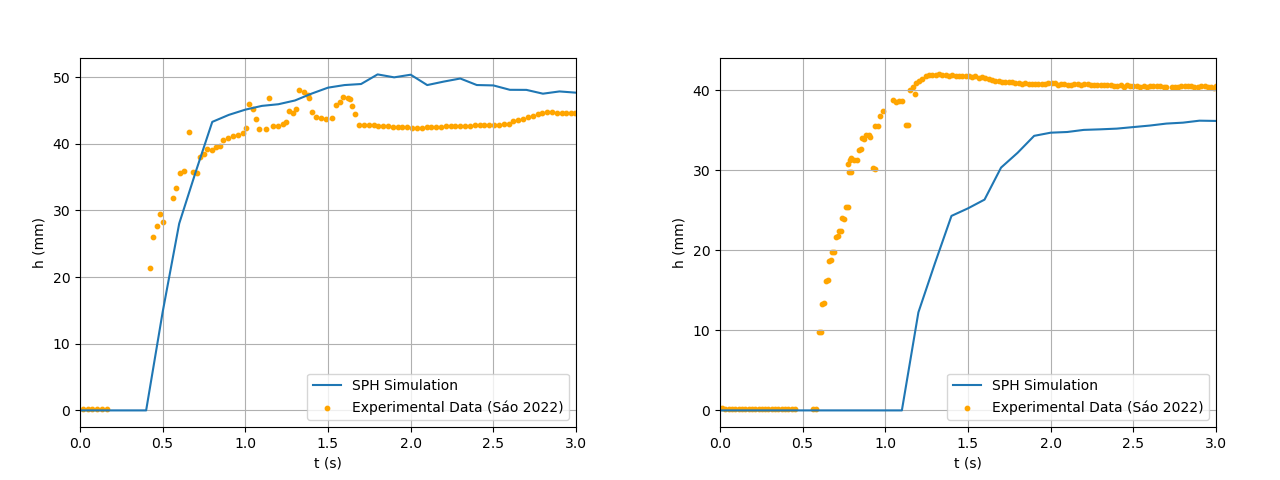

is set to  for the three-dimensional kernel. The simulation results are presented in Figures 15 and 16 and the error evolution is presented in figure 17. The average relative errors for this simulation’s flow reach were 10% and the sensors presented errors of 13% and 22%, respectively, which indicates a good level of agreement between simulated and experimental data.

for the three-dimensional kernel. The simulation results are presented in Figures 15 and 16 and the error evolution is presented in figure 17. The average relative errors for this simulation’s flow reach were 10% and the sensors presented errors of 13% and 22%, respectively, which indicates a good level of agreement between simulated and experimental data. | Figure 15. SPH Results for the Dambreak Wave Reach Throughout the Simulation Using Cubic Kernel |

| Figure 16. SPH Results for Depth Below each Sensor (1 on the left and 2 on the right) Throughout the Simulation Using Cubic Kernel |

| Figure 17. Relative Error Throughout the Simulation for Cubic Spline Kernel |

4.7.2. Wendland

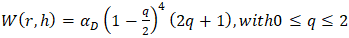

- In this case, the smoothing kernel employed is a quintic equation [34]:

| (16) |

is set to

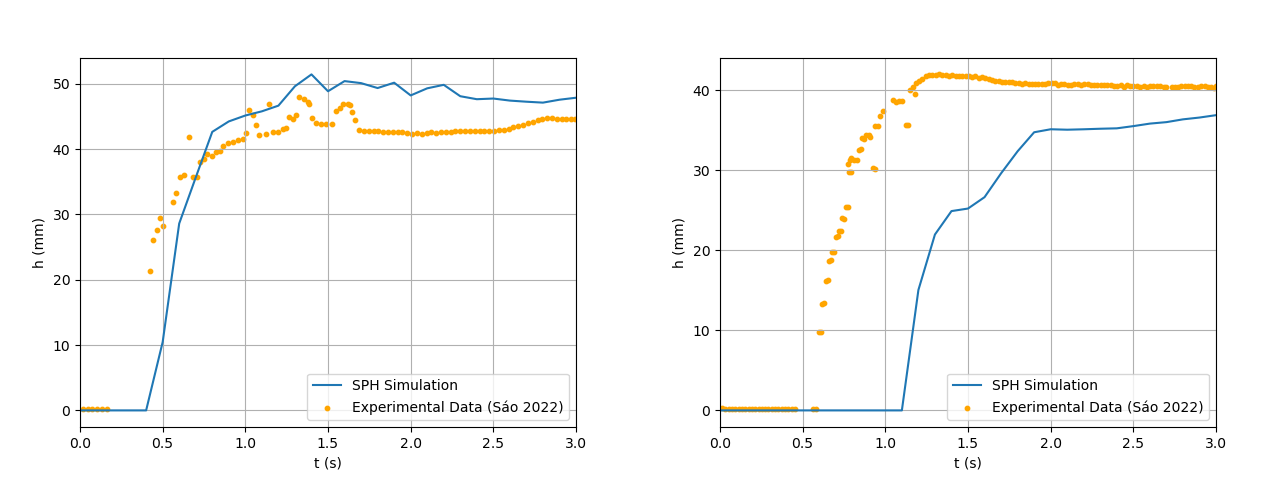

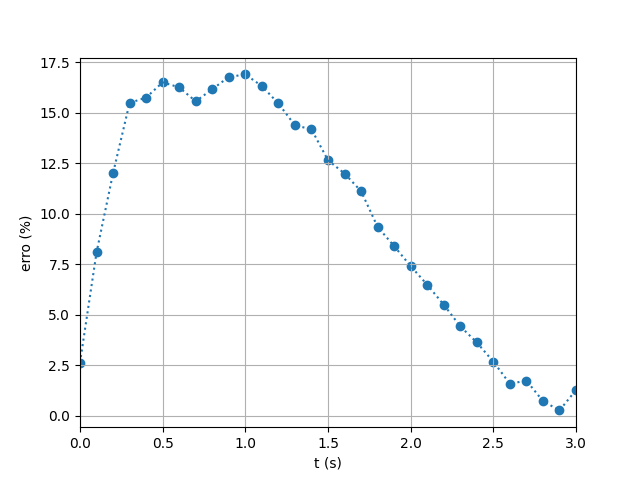

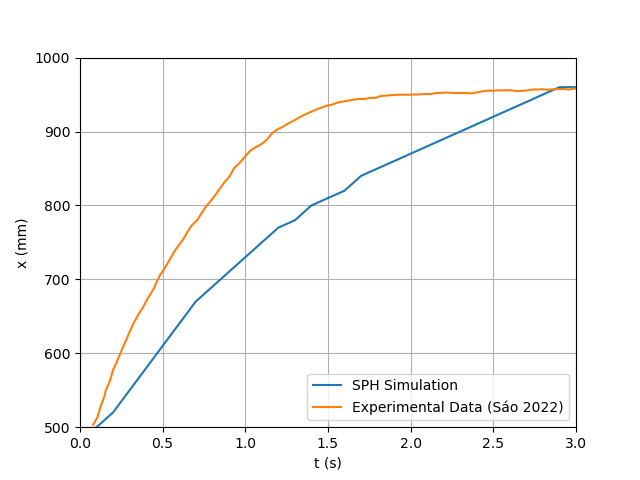

is set to  for the three-dimensional kernel. This also being a polynomial equation means it will also benefit from reduced run times.The simulation results and comparison to experimental data are shown in figures 18 and 19 and the The relative error calculated for the simulation results using the Wendland kernel are shown in Figure 20. The average relative error was 10% for the reach and 12% and 23% for each sensor, which shows a good level of agreement between simulated and experimental data, just as the cubic spline kernel.

for the three-dimensional kernel. This also being a polynomial equation means it will also benefit from reduced run times.The simulation results and comparison to experimental data are shown in figures 18 and 19 and the The relative error calculated for the simulation results using the Wendland kernel are shown in Figure 20. The average relative error was 10% for the reach and 12% and 23% for each sensor, which shows a good level of agreement between simulated and experimental data, just as the cubic spline kernel. | Figure 18. SPH Results for the Dambreak Wave Reach Throughout the Simulation Using Wendland Kernel |

| Figure 19. SPH Results for Depth Below each Sensor (1 on the left and 2 on the right) Throughout the Simulation Using Wendland Kernel |

| Figure 20. Relative Error Throughout the Simulation for Wendland Kernel |

4.8. Artificial Viscosity

- Artificial viscosity serves as a crucial technique in SPH formulations to mitigate shock discontinuities. Its primary function is to eliminate gaps between particles, thereby reducing inter-particle penetration and enhancing the simulation’s resemblance to a continuous domain of fluid [35]. In this study, we assessed the effectiveness of two viscosity schemes. The first is a widely adopted approach [35], while the second involves a more sophisticated combination of laminar viscosity and sub-particle turbulence introduced by [11].

4.8.1. Using Artificial Viscosity

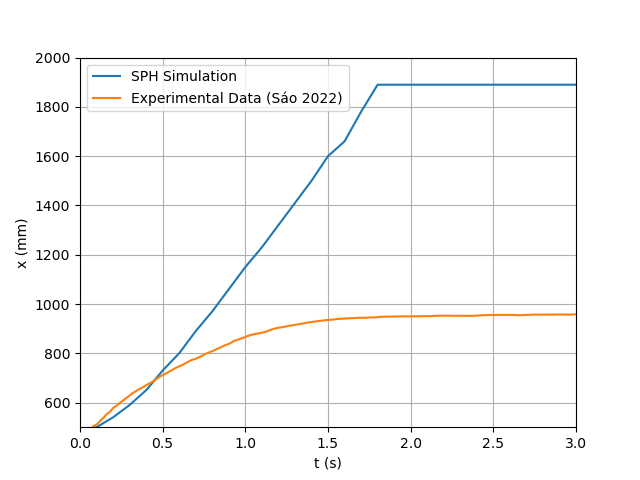

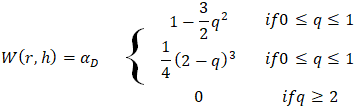

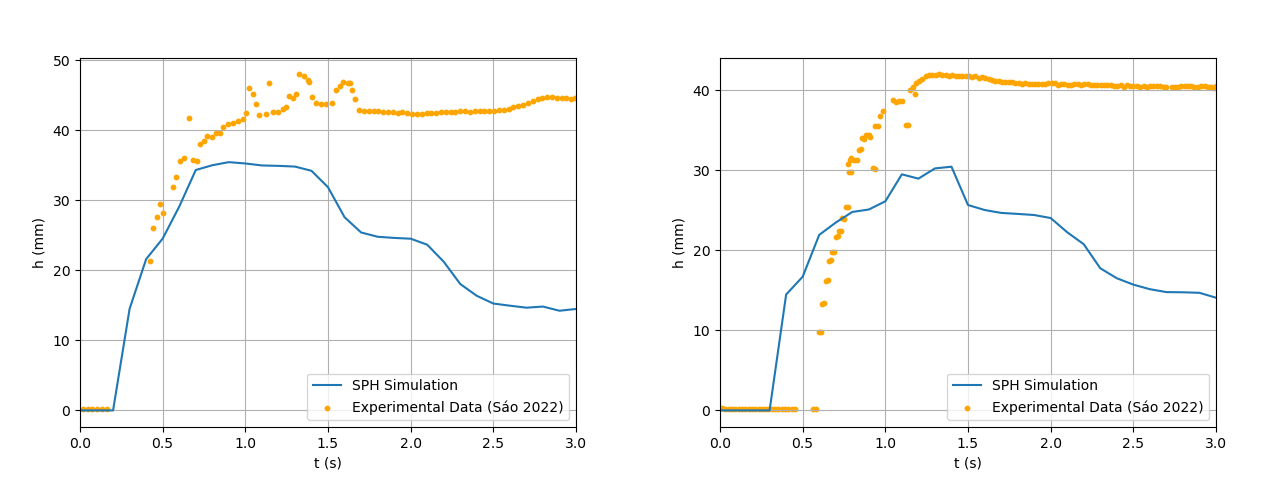

- The outcomes of employing standard artificial viscosity are depicted in Figures 21 and 22. This approach was originally designed for Newtonian flows and shock-dominated regimes, and it proved inadequate for representing the yield-stress behavior of the Carbopol gel used in the experiments. Notably, it fails to adequately produce the expected deacceleration as the fluid flows, resulting in a deviation from the experimental results.The artificial viscosity’s employment’s failure to capture the rheological properties is further enforced by the calculation of the relative errors, as shown in Figure 23 for the dambreak reach. The average relative error throughout the simulation was of 77% for the dambreak reach and of 39% and 64% for depth below the first and second sensors. Such high discrepancies reveal that the artificial viscosity formulation distorts the flow dynamics and cannot be relied upon for accurate representation of non-Newtonian fluids.

| Figure 21. SPH Results for the Dambreak Wave Reach Throughout the Simulation Using Artificial Viscosity |

| Figure 22. SPH Results for Depth Below each Sensor (1 on the left and 2 on the right) Throughout the Simulation Using Artificial Viscosity |

| Figure 23. Relative Error Throughout the Simulation Using Artificial Viscosity |

4.8.2. Laminar Viscosity and Sub-Particle Turbulence

- In contrast, the scheme employing laminar viscosity and sub-particle turbulence, showcased in Figures 24 and 25, more accurately reproduces the rheological properties of the fluid. The relative error calculated for the simulation results using the laminar and sub- particle turbulence artificial viscosity scheme are shown in Figure 26. The average relative error was 10% for the reach and 12% and 23% for sensor 1 and 2, respectively.This method introduces an explicit laminar term that captures the base viscous resistance of the fluid while the sub-particle turbulence component accounts for unresolved small-scale turbulence. Together, they allow a more realistic representation of the internal energy dissipation mechanisms in yield-stress materials.The corresponding relative errors (Figure 26) further support this conclusion. The average relative error for the wave reach was 10%, and 12% and 23% for sensors 1 and 2, respectively, a dramatic improvement over the standard formulation.

| Figure 24. SPH Results for the Dambreak Wave Reach Throughout the Simulation Using Laminar and Sub Particle Turbulence |

| Figure 25. SPH Results for Depth Below each Sensor (1 on the left and 2 on the right) Throughout the Simulation Using Laminar and Sub Particle Turbulence |

| Figure 26. Relative Error Throughout the Simulation Using Laminar and Sub Particle Turbulence |

4.9. Remaining Scenarios

- Three options for artificial density diffusion and two choices for time-stepping schemes were considered with the lack of a clear best choice among the individual options, we opted for a comparison of all six possible combinations. This approach allowed us to delve deeper than individual evaluations and look for subtle improvements visible due to the combination of these parameters.

4.9.1. Time-Stepping

- As with other computational fluid dynamics models, the time-stepping scheme plays a crucial role in maintaining stability and ensuring convergence of the Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics model. While explicit solvers are popular due to their computational efficiency, they can be susceptible to instabilities.As a first approach, we explored the Verlet time-stepping scheme introduced by [36]. Its popularity in particle dynamics stems from its computational efficiency, making it attractive for large SPH simulations. The Verlet scheme updates particle positions, velocities, and densities at each time step. However, due to the decoupling of the density equation in SPH, an intermediate time-step is necessary for updating density before advancing positions and velocities. This additional step slightly increases the computational cost compared to a fully Verlet-compatible density update, but it maintains stability and accuracy in SPH simulations.We also investigated a hybrid symplectic-Verlet time-stepping scheme. This approach combines the stability and energy-preserving properties of symplectic integration with the computational efficiency of the Verlet scheme for certain variables. This scheme follows the formulation proposed in Ref. [37], applying symplectic integration to update particle velocities and positions. Meanwhile, the formulation proposed for density calculations in Ref. [38] is also adopted.

4.9.2. Density Diffusion

- To mitigate density fluctuations and reduce noise caused by shocks and turbulent flows an artificial density diffusion scheme was introduced [39]. This approach evens out density values among neighboring particles, promoting a smoother density distribution throughout the computational domain.Beyond the original formulation [39], we test one other way to calculate the density diffusion and the model without density diffusion for comparison. The second formulation tested was proposed in Ref. [40], by Fourtakas et al., in a way to improve the behaviour of particle’s density values close to boundaries.

5. Results and Discussion

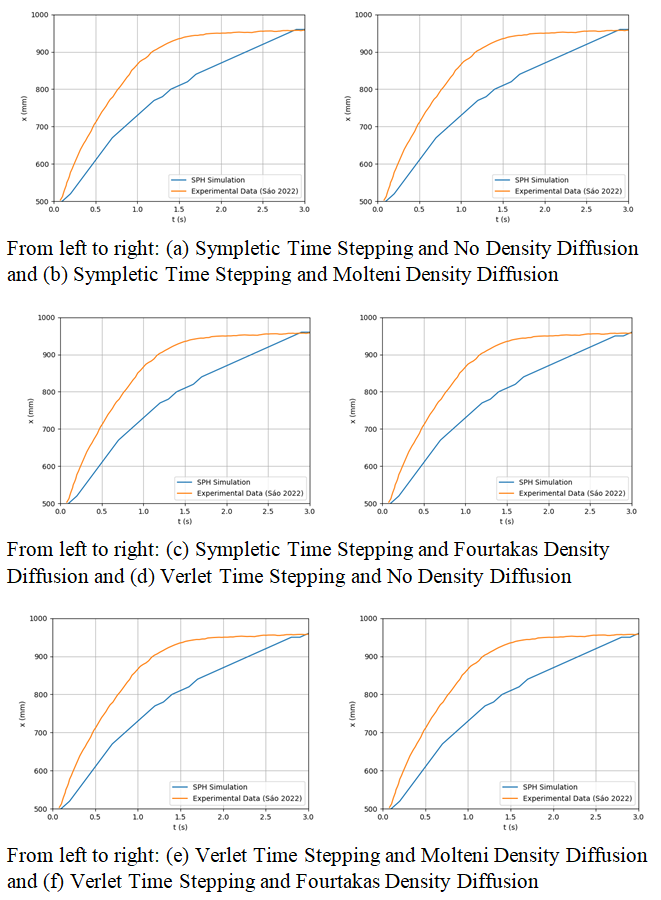

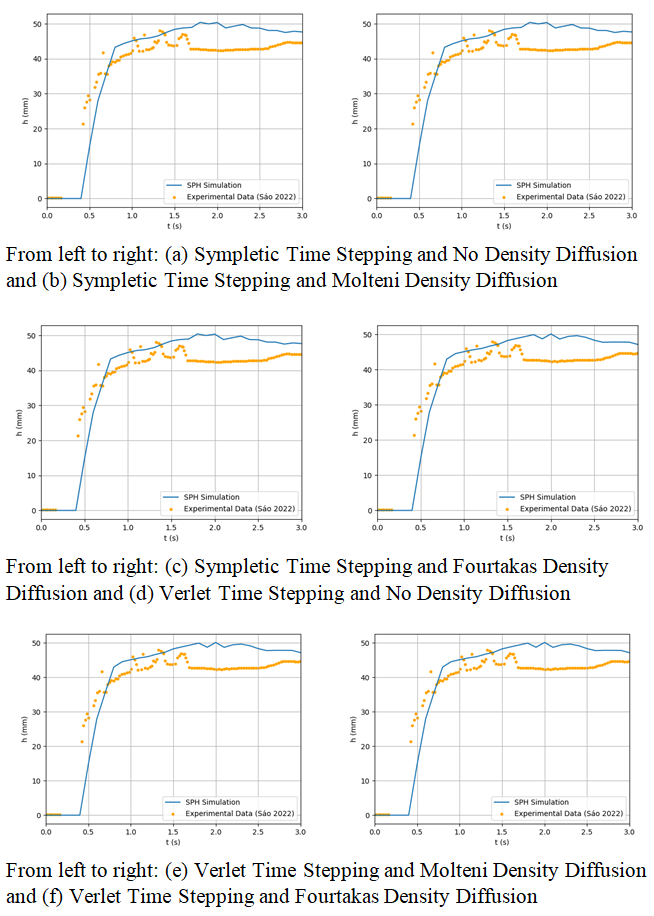

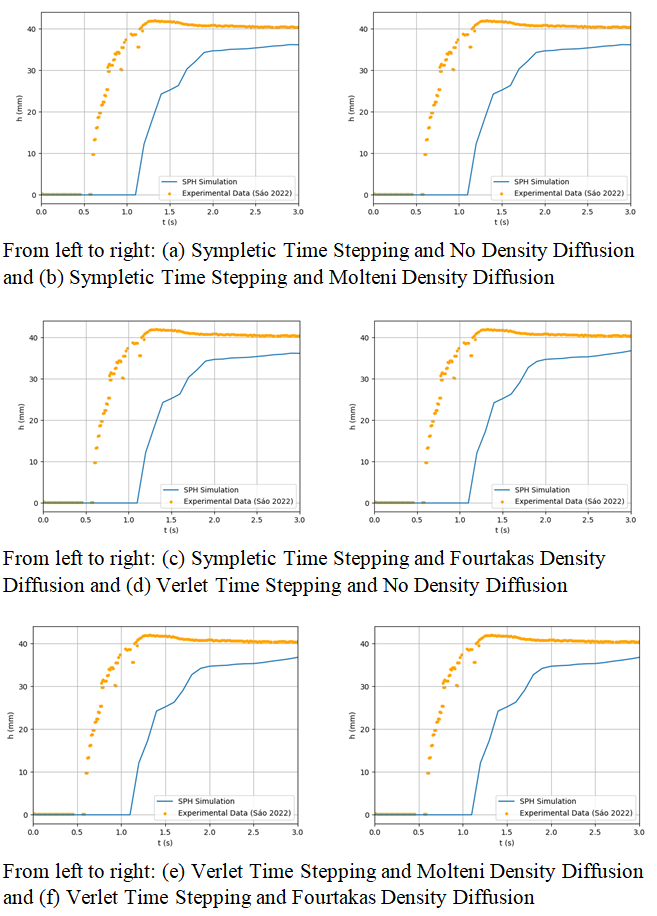

- The results for the dam break reach for combinations of the time stepping and density diffusion are shown in Figure 27 while the depth below the sensors are compared in Figure 28 for the first sensor, and in Figure 29 for the second one.

| Figure 27. From (a) to (f), SPH Results for the Dambreak Wave Reach Throughout the Simulation For the Remaining Scenarios |

| Figure 28. From (a) to (f), SPH Results for Depth Below the First Sensor Throughout the Simulation for The Remaining Scenarios |

| Figure 29. From (a) to (f), SPH Results for Depth Below the Second Sensor Throughout the Simulation for The Remaining Scenarios |

6. Conclusions

- The adjusted non-Newtonian formulation appeared to closely mimic the behavior of the original Herschhel-Bulkley model. Since the objective was to help the lower deformation stages of the flow not to deal with too high apparent viscosities, the formulation used was proven to be suitable for its use.Ultimately, we couldn’t properly adjust the model simulation to fit the experimental data. While certain aspects exhibited agreement between the simulated and the mea- sured, notably the middle section of the dam-break flow and the fluid depth measured below both sensors, it was not enough to fit the entire simulated results to experimental data.Since most of the disparity occurred in the early to middle parts of the simulation, the way the moving dam was implemented might be the source of the disparity. As previously mentioned, the boundary particles interact with the fluid particles by increasing density around them and preventing fluid particles from crossing. The gap they might form around that was accounted for during the boundary setup might not work properly around the moving dam, causing repulsion between boundary and fluid when there shouldn’t be, especially below the dam while it rises. This may prevent the fluid from flowing when it should flow, during the first time steps, and constrain flow in a way it shouldn’t, during the middle steps of the simulation. As the dam stops influencing the flow, it matches the experimental data better in the later stages of the simulation.Because of this, we assume that to accurately match the simulation results to the experimental data, it is necessary to fix the way the rising dam influences the flow. This could be done by changing the boundary properties and setting them up differently. One potential approach would be to implement the boundary conditions proposed in Ref. [41], which involves incorporating ghost particles outside the domain and updating them during SPH particle updates, as suggested in Ref. [42].

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML