-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Genetic Engineering

p-ISSN: 2167-7239 e-ISSN: 2167-7220

2026; 14(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.ijge.20261401.01

Received: Nov. 30, 2025; Accepted: Dec. 19, 2025; Published: Jan. 5, 2026

Heritability, Genetic Advance, and Correlation of Agro-Morphological Traits in Interspecific Simple and Complex Cotton Hybrids

A. A. Iskandarov 1, M. K. Kudratova 2, O. A. Mukhammadiev 2, F. U. Rafieva 3, F. N. Kushanov 3, 4

1Senior Lecturer, Chirchik Branch of Tashkent State Medical University, Uzbekistan

2Assistant Teacher, Tashkent State Medical University, Uzbekistan

3DSc in Biological Sciences, Institute of Genetics and Plant Experimental Biology, Academy of Sciences, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

4Professor, National University of Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: A. A. Iskandarov , Senior Lecturer, Chirchik Branch of Tashkent State Medical University, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study evaluated phenotypic (PCV), genotypic (GCV), and environmental (ECV) coefficients of variation, broad-sense heritability (h²), and expected genetic gain (GG, GG%) for agro-morphological traits, as well as inter-trait correlations, in interspecific F1 complex and F4 simple cotton hybrid populations derived from designated parental forms. Field phenotyping was conducted in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications for the following traits: boll weight, staple length, lint percentage, 1000-seed weight, main-stem height, number of fruiting branches, number of bolls per plant, and number of open bolls per plant. In the F1 complex hybrids, GCV approximated PCV and h² was high for most traits; notably, the numbers of open bolls and total bolls per plant showed large GG%, confirming their capacity to deliver rapid, reliable selection responses at early generations. Boll weight in F1 also exhibited high h² with appreciable GG%, indicating expanded early-stage potential. Conversely, negative associations of fruiting-branch number with certain yield and quality components underscore the need to regulate plant architecture. Staple length and lint percentage displayed stable inheritance in F1 under low ECV. In F4 simple hybrids, boll weight was environmentally sensitive (large PCV–GCV, low h²) and thus required multi-location confirmation; however, positive linkages among open bolls, total bolls, and lint percentage remained strong.

Keywords: Cotton (Gossypium spp.), F1 complex hybrid, F4 simple hybrid, PCV–GCV–ECV, Heritability (h²), Genetic gain (GG, GG%), Number of open bolls per plant

Cite this paper: A. A. Iskandarov , M. K. Kudratova , O. A. Mukhammadiev , F. U. Rafieva , F. N. Kushanov , Heritability, Genetic Advance, and Correlation of Agro-Morphological Traits in Interspecific Simple and Complex Cotton Hybrids, International Journal of Genetic Engineering, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2026, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.ijge.20261401.01.

1. Introduction

- Cotton (Gossypium spp.) is one of the cornerstone crops of national agriculture and the textile industry; achieving sustained gains in yield and fiber quality remains a primary goal of breeding programs. Under conditions of increasing climate stress, water scarcity, and agronomic heterogeneity, it is essential to broaden genetic variation and to evaluate it rigorously using quantitative-genetic metrics in order to identify high-performing genotypes that are stable across environments [5]. In this context, the phenotypic (PCV), genotypic (GCV), and environmental (ECV) coefficients of variation, broad-sense heritability (h²), and expected genetic gain (GG, GG%) are key diagnostic parameters: the PCV–GCV gap reflects the enviromental share of variation, whereas h² indicates the potential genetic response to selection [2], [9], [1].Interspecific F1 complex and F4 simple hybrid populations derived from designated parents provide a convenient model for revealing genetic architecture and dispersion. At the F1 stage, GCV typically approximates PCV and h² is high, enabling rapid and reliable early-generation selection; at the F4 stage, recombinational dispersion broadens, transgressive segregants may emerge, and evaluating G×E effects becomes more important [1], [3]. In cotton, yield-proximal traits—bolls per plant and open bolls per plant—usually show high h² and large GG%, while lint percentage and staple length tend to inherit stably under low ECV, allowing early quality control [12], [21]. By contrast, mass-related traits such as single-boll seed-cotton weight are often environmentally sensitive and therefore require decisions based on multi-location, replicated testing [3]. Accordingly, the objective of this study is to perform a systematic assessment of PCV, GCV, ECV, h², and GG (GG%) for major agro-morphological traits in F1 (complex) and F4 (simple) hybrid populations, and to characterize the intertrait correlation structure with the aim of identifying genotypes suitable for effective selection.

2. Materials and Methods

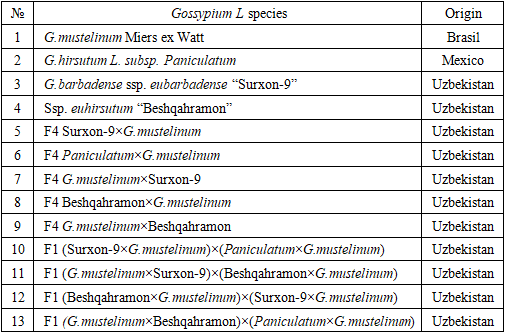

- Experimental site, period, and agronomic managementField experiments were conducted during 2021–2024 at the regional experimental field of the Institute of Genetics and Plant Experimental Biology, Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, located in Zangiota district, Tashkent region. The experimental site is situated approximately 0.5 km northeast of Tashkent city at 41°20′ N latitude, 69°18′ E longitude, along the upper terrace of the Chirchiq River, at an altitude of 398 m above sea level.The soil of the experimental field is classified as typical light gray soil, characterized by low humus content and a medium loamy texture. The terrain is slightly sloped, non-saline, with weak natural infestation by Verticillium wilt, and with deep groundwater levels (7–8 m). The climate of the region is sharply continental, featuring hot summers (June–August), cold winters (especially December–January), 175–185 sunny days, and a frost-free period of 200–210 days. Precipitation mainly occurs in autumn, winter, and spring, whereas summers are dry, necessitating supplementary irrigation for cotton cultivation.All agronomic practices were carried out according to the standard management protocols adopted at the Institute’s experimental farm. In autumn, fields were cleared of cotton residues and deep-plowed to a depth of 35 cm. In early spring, harrowing was performed to conserve soil moisture and suppress early weed emergence. Sowing was conducted in the third decade of April using a 90 × 20 × 1 cm planting scheme, with seeds placed at a depth of 4–5 cm. Inter-row cultivation, weed control, and irrigation were applied in an integrated manner throughout the growing season. Pest control included the application of GXSG against cotton bollworm and BI-58 against aphids at a rate of 2.0–2.5 kg per ton of water.

|

3. Results

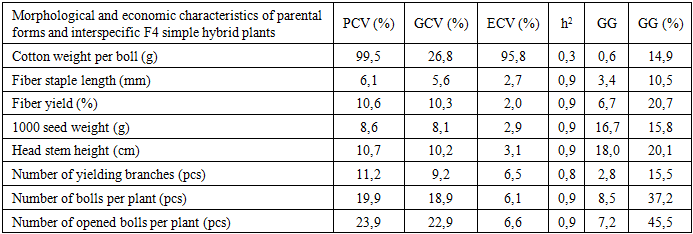

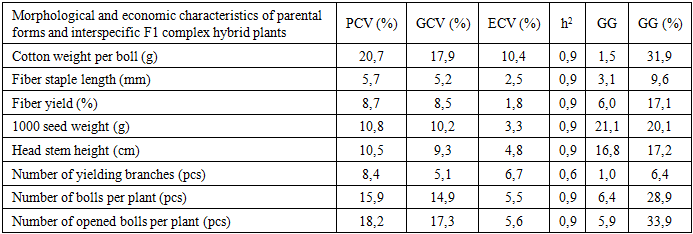

- The genotypic, phenotypic, and environmental coefficients of variation for the studied traits in the parental varieties and their F4 simple and F1 complex hybrids are presented in Tables 2–3. In the parental forms and interspecific F4 simple hybrids, the genotypic coefficient of variation (GCV) and the phenotypic coefficient of variation (PCV) ranged from 5.6% to 26.78% and from 6.15% to 99.49%, respectively.

|

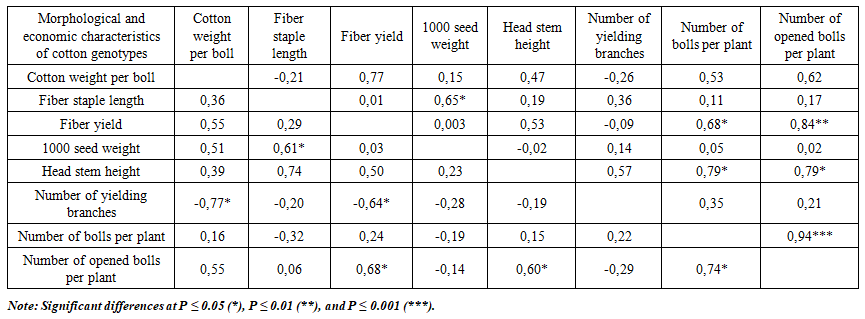

| Table 4. Correlations for agro-morphological characters in cotton: F4 simple hybrids (upper triangle) and F1 complex hybrids (lower triangle), both including parental forms |

4. Discussion

- This study compared variation and inheritance parameters for key agro-morphological traits in parental forms and interspecific F1 complex and F4 simple hybrid populations. At the F1 stage, most traits exhibited GCV ≈ PCV with low–moderate ECV and high h², indicating that a large share of phenotypic variance is genotypic and that early-generation selection can be both rapid and reliable. By contrast, in the F4 population single-boll seed-cotton weight showed very high ECV (≈95%) and low h², revealing strong environmental sensitivity and arguing for decisions based on later-stage, multi-location testing. In sharp contrast to boll mass, traits such as lint percentage, staple length, 1000-seed weight, main-stem height, bolls per plant, and especially open bolls per plant combined high h² with small PCV–GCV gaps and appreciable GG%, marking them as priorities for early selection.These patterns are consistent with classical quantitative-genetic principles: PCV reflects total (phenotypic) dispersion whereas GCV isolates the genotypic component; thus a small PCV–GCV gap implies a limited environmental share [5]. High h² accompanied by substantial GG% typically signals the predominance of additive gene action, predicting good response to straightforward mass selection [9], [1]. Conversely, low h² with a large PCV–GCV difference implicates stronger environmental and G×E effects, for which designs with more replications and sites are warranted [2]. Our F4 boll-mass example fits this latter scenario; although F1 showed a more favorable signal (h² = 0.86; GG% = 31.88), confirmation across environments remains prudent.Yield-proximal components—open bolls per plant and bolls per plant—consistently delivered the largest expected gains (F4: 45.49% and 37.22%; F1: 33.88% and 28.95%), providing a robust early-selection core for yield improvement. Among quality traits, lint percentage (F1 h² = 0.98; F4 h² = 0.97) and staple length (F1 h² = 0.90; F4 h² = 0.91) remained under stable genetic control against low ECV, allowing them to function as early filter criteria that safeguard a minimum quality threshold during yield-oriented selection. Correlation analysis further supported indirect selection: open bolls per plant correlated strongly and positively with lint percentage, plant height, and bolls per plant, simplifying simultaneous improvement of yield and fiber traits. At the same time, in F1 the number of fruiting branches showed negative associations with certain yield/quality components (e.g., boll mass and lint percentage), highlighting the need to regulate plant architecture rather than increase branching indiscriminately.Overall, the evidence suggests a staged strategy: leverage high-heritability, high-GG% traits (especially open bolls and total bolls per plant) for early-generation advancement, apply quality filters via lint percentage and staple length, and defer decisions on environment-sensitive traits such as boll mass to multi-environment, later-generation trials. This integrated approach aligns with quantitative-genetic expectations and maximizes the likelihood of achieving concurrent gains in yield and fiber quality under variable production environments.

5. Conclusions

- This study revealed differential expression of agronomic traits (phenotypic divergence) across combinations. Specifically, in F1 complex hybrids lint percentage reached up to 39%, 1000-seed weight up to 133.6 g, main-stem height 100–115 cm, and number of fruiting branches 14–16. In F4 simple hybrids, lint percentage ranged 22–38%, 1000-seed weight 78–122 g, main-stem height 70–120 cm, and fruiting branches 13–19. These contrasts confirm that hybrid genetic components and their heritable potential play a decisive role in shaping phenotypic differences.Overall, the results indicate that complex (F1) hybrids possess genetic advantages over simple (F4) hybrids for several key traits, supporting their preferential use in breeding programs. Leveraging these genetic gains—while validating environment-sensitive traits in multi-environment trials—should enhance breeding efficiency and deliver genotypes with improved yield and fiber quality.

References

| [1] | Allard, R. W. (1960). Principles of plant breeding. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. |

| [2] | Burton, G. W., & DeVane, E. H. (1953). Estimating heritability in tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea) from replicated clonal material. Agronomy Journal, 45, 478–481. |

| [3] | Eberhart, S. A., & Russell, W. A. (1966). Stability parameters for comparing varieties. Crop Science, 6, 36–40. |

| [4] | Eswari, K. B., Rekha, G., & Reddy, V. K. (2017). Studies on heritability and genetic advance in upland cotton. International Journal of Pure & Applied Bioscience, 5, pp. |

| [5] | Falconer, D. S., & Mackay, T. F. C. (1996). Introduction to quantitative genetics (4th ed.). Longman. |

| [6] | Ganesan K.N. and Raveendranm, T.S. (2007). Enhancing the breeding value of genotype through genetic selection in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Bulletin of the Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Kyushu University, 30, 1-10. |

| [7] | Guinn, G., & Mauney, J. R. (1984). Fruiting of cotton: I. Boll development and relationships to plant growth. Agronomy Journal, 76, pp. |

| [8] | Hazel, L. N. (1943). The genetic basis for constructing selection indexes. Genetics, 28, 476–490. |

| [9] | Johnson, H. W., Robinson, H. F., & Comstock, R. E. (1955). Estimates of genetic and environmental variability in soybeans. Agronomy Journal, 47, 314–318. |

| [10] | Kumari, S. R., & Chamundeshwari, N. (2005). Studies on genetic variability, heritability and genetic advance in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Research on Crops, 6(1), 98–99. |

| [11] | Mahalingam, A., Saraswathi, R., Ramalingam, J., & Jayaraj, T. (2013). Genetics of floral traits in cytoplasmic male sterile (CMS) and restorer lines of hybrid rice (Oryza sativa L.). Pakistan Journal of Botany, 45(6), 1897–1904. |

| [12] | Meredith, W. R., Jr., & Bridge, R. R. (1972). Heterosis and gene action in cotton. Crop Science, 12, 304–310. |

| [13] | Nizamani, F., Baloch, M. J., Baloch, A. W., Buriro, M., Nizamani, G. H., Nizamani, M. R., & Baloch, I. A. (2017). Genetic distance, heritability and correlation analysis for yield and fiber quality traits in upland cotton genotypes. Pakistan Journal of Biotechnology, 14(1), 29–36. |

| [14] | Panse, V. G. (1957). Genetics of quantitative characters in relation to plant breeding. Indian Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding, 17, 318–328. |

| [15] | Pujer, S., Siwach, S. S., Deshmukh, J., Sangwan, R. S., & Sangwan, O. (2014). Genetic variability, correlation and path analysis in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Electronic Journal of Plant Breeding, 5(2), 284–289. |

| [16] | Rao, P. J. M., & Reddy, V. N. (2001). Variability, heritability and genetic advance in yield and its components in cotton. Journal of Research ANGRAU, 29-35. |

| [17] | Rokadia, P., & Vaid, B. (2003). Variability parameters in American cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Annals of Arid Zone, 42(1), 105–106. |

| [18] | Rosenow, D., Quisenberry, J., Wendt, C., & Clark, L. (1983). Drought-tolerant sorghum and cotton germplasm. Agricultural Water Management, 7, 207–222. |

| [19] | Saleem, S., Kashif, M., Hussain, M., Khan, A., & Saleem, F. A. (2016). Genetic behavior of morpho-physiological traits and their role in breeding drought-tolerant wheat. Pakistan Journal of Botany, 48(3), 925–932.* |

| [20] | Smith, H. F. (1936). A discriminant function for plant selection. Annals of Eugenics, 7, 240–250. |

| [21] | Ulloa, M., Meredith, W. R., Jr., Shappley, Z. W., & Kahler, A. L. (2005). RFLP genetic linkage maps in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 110, 1153–1162. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML