-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Genetic Engineering

p-ISSN: 2167-7239 e-ISSN: 2167-7220

2025; 13(12): 316-321

doi:10.5923/j.ijge.20251312.08

Received: Nov. 28, 2025; Accepted: Dec. 21, 2025; Published: Dec. 26, 2025

Biological Risks of Insufficient Healthy Eating Culture Among Primary School Students and Improving Preventive Measures (In the Conditions of Namangan City)

Ulukhujaeva Nozima Narzullokhonovna

Independent Researcher, Namangan State University, Namangan, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Ulukhujaeva Nozima Narzullokhonovna, Independent Researcher, Namangan State University, Namangan, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This article presents a comprehensive analysis of the actual dietary patterns of primary school children aged 9-11 years in the city of Namangan, based on a survey of 194 families residing in both central and peripheral urban districts. The study aims to assess the degree to which children’s nutrition aligns with current recommendations issued by the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF and national guidelines for healthy school nutrition. The findings reveal significant deviations from the principles of balanced nutrition, including irregular meal schedules, frequent skipping of breakfast, and insufficient intake of dairy products, fish, vegetables and fruits. The analysis also shows that a considerable proportion of children consume sugar-sweetened beverages, fast food and confectionery on a daily basis, increasing the risk of overweight, metabolic disorders and micronutrient deficiencies. The results indicate that 70% of parents acknowledge that their children’s out-of-home nutrition is unhealthy, while more than half report difficulties in maintaining a regular eating routine. Substantial differences in the frequency of consuming healthy and unhealthy foods were observed across the three age groups. The identified dietary shortcomings may negatively affect children’s health through weakened immunity, increased risk of anemia and vitamin deficiencies (including vitamin D deficiency), impaired growth and reduced cognitive performance. The article proposes practical measures to improve the nutritional status of school-aged children, including the introduction of structured school breakfast programs, development of local menu standards, enhancement of parents’ nutritional literacy, restrictions on the sale of unhealthy foods in schools and implementation of regular monitoring of children’s micronutrient status. The findings highlight the necessity of a comprehensive, multisectoral approach to shaping healthy dietary habits both at home and in educational institutions.

Keywords: Child nutrition, Primary school age, Diet, Dairy products, Vegetables and fruits, Fast food, Prevention

Cite this paper: Ulukhujaeva Nozima Narzullokhonovna, Biological Risks of Insufficient Healthy Eating Culture Among Primary School Students and Improving Preventive Measures (In the Conditions of Namangan City), International Journal of Genetic Engineering, Vol. 13 No. 12, 2025, pp. 316-321. doi: 10.5923/j.ijge.20251312.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Nutrition for children of primary school age is a key factor in their physical, cognitive, and emotional development. The World Health Organization emphasizes that the diet of children aged 7-11 years should ensure adequate intake of energy, proteins, vitamins, and minerals, including calcium, iron, iodine, and vitamin D [1]. This age period is characterized by intensive body growth and active formation of attention, memory, and learning functions, which makes the quality of nutrition particularly important [2].According to international reports, in the countries of Central Asia, including Uzbekistan, there are still serious dietary structure disorders among children, associated with insufficient consumption of dairy products, fish, vegetables, and fruits [3]. One of the most relevant indicators is the “double burden of malnutrition” a condition in which children simultaneously experience micronutrient deficiencies (vitamin D, iron, calcium) and excessive intake of sugar, fast food, and high-fat products [4]. Such a combination leads to weakened immunity, risk of anemia, stunted growth, and an increased likelihood of obesity [5].UNICEF notes that irregular eating patterns and skipping breakfast are widespread nutritional problems among school-aged children in the region [3]. International studies confirm that children who do not receive a complete breakfast have lower indicators of concentration and academic performance [6].Nutrition of primary school-aged children is strongly influenced by the school environment, which plays an important role in shaping dietary habits. School breakfast programs developed by the WHO and the World Food Programme have proven effective in improving cognitive functions, reducing absenteeism, and normalizing children’s nutritional status [7]. The implementation of school nutrition standards in the European region has led to a 15–20% reduction in children’s intake of sugar and salt over several years [8]. Considering the combination of traditional and modern dietary trends in Uzbekistan, as well as the increasing availability of high-calorie foods, studying the actual nutrition of primary school children in the city of Namangan is a timely and important task. Such research will make it possible to identify the most common dietary disorders and develop recommendations based on international standards of healthy nutrition.Rational nutrition is a critical condition for healthy growth, cognitive development, and the prevention of chronic diseases among children. According to the Global Nutrition Report, the quality of children’s diets in low- and middle-income countries, including Uzbekistan, is characterized by reduced consumption of natural sources of proteins, vitamins, and minerals, while the proportion of ultra-processed foods is increasing [9]. The WHO emphasizes the necessity of daily consumption of dairy products, fish, vegetables, and fruits as key sources of calcium, vitamin D, iron, and dietary fiber [10]. Insufficient intake of these foods increases the risk of anemia, impaired bone development, and weakened immune resistance.UNICEF notes that irregular eating patterns, skipping breakfast, and low dietary diversity remain widespread among school-aged children in Central Asia, leading to micronutrient deficiencies among a significant proportion of them [11]. International studies show that complete school breakfasts have a positive impact on cognitive functions: children who regularly receive breakfast demonstrate higher attention, memory, and academic performance compared to those who skip the morning meal [12].The “double burden of malnutrition” the simultaneous presence of micronutrient deficiencies and excessive intake of sugar, salt, and fats is considered by FAO and WHO to be one of the most serious threats to children’s health today [13]. This condition is linked to the rapid spread of fast food, sugary beverages, and high-calorie snacks, especially in urban areas. Research published in the journal Nutrients indicates that consuming fast food more than twice a week increases the risk of obesity by 27-30% and negatively affects attention levels among schoolchildren [14]. Reports from WHO Europe highlight that the introduction of mandatory standards limiting the content of sugar, salt, and fats in school meals leads to improved dietary habits and a reduction in metabolic disorders among children [15].Moreover, systematic reviews confirm a direct relationship between parents’ nutritional knowledge and the quality of children’s diets. Higher parental nutritional literacy is associated with more regular eating habits and increased consumption of healthy foods among their children [16].

2. Materials and Methods

- The actual nutrition of children in “home” conditions was examined using a questionnaire survey. The developed questionnaire contained fixed questions regarding the dietary regimen and qualitative composition of the diet, with a set of possible answers for each question. A survey was conducted among 194 families residing in both central and peripheral districts of the city of Namangan. The respondents were divided into three groups based on the age of the children: the first group included parents of 11-year-old children from 70 families; the second group consisted of parents of 10-year-old children from 61 families; and the third group comprised parents of 9-year-old children from 63 families.

3. Results of the Study

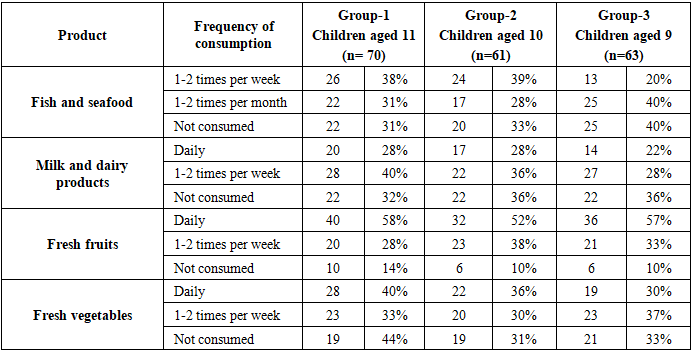

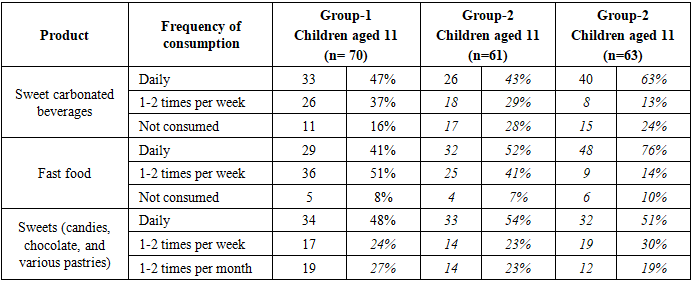

- During the survey, 136 parents (70%) of schoolchildren acknowledged that their child eats irrationally outside the home and does not follow a proper dietary regimen, while 58 parents (30%) were convinced that their children’s nutrition is appropriate. Most parents do not have a clear understanding of such a crucial criterion in the organization of healthy nutrition as a dietary regimen. Only 103 respondents (53%) reported that they follow a meal schedule during weekends, whereas 91 parents (47%) feed their children irregularly whenever the child wants to eat or when they are in a good mood.The parental survey also revealed that many children - 52 (27%) - do not like breakfast. A total of 91 schoolchildren (47%) consume sandwiches, sweets, sausages, biscuits, jam, and similar foods for breakfast. Meanwhile, 51 students (26%) have a varied and rational breakfast that includes milk porridges, dairy products, different types of nuts, omelets, pancakes, dried fruits, and other nutritious foods.The analysis of the diet of primary school-aged children regarding the availability of fish, dairy products, fresh fruits, and vegetables is presented in the following table.

|

|

4. Discussion

- The obtained data clearly demonstrate pronounced disturbances in the dietary structure of primary school-aged children in Namangan. The dominant factors include a deficiency of fish and dairy products, insufficient consumption of vegetables, and moderate intake of fruits, while sweet carbonated beverages, fast food, and confectionery products are frequently present in the diet. These results are consistent with UNICEF reports on Central Asia, which indicate that similar dietary problems are observed among a significant proportion of children in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan [17].The identified dietary imbalances among schoolchildren reflect elements of the double burden of malnutrition, in which a deficiency of essential micronutrients coexists with an excess intake of sugar and saturated fats. This condition is described in detail in the WHO analytical review (2022), where attention is drawn to the increasing prevalence of such disturbances among children in urban areas of transition-economy countries [18]. Low consumption of milk and fish, as observed in our study, can potentially lead to deficiencies in calcium, vitamin D, omega-3 fatty acids, and high-quality protein. Similar deficiencies, according to Global Nutrition Report 2024, are typical for child populations in regions with limited access to quality animal-based products [19].Comparison of our findings with international studies reveals similar trends. According to UNICEF (2022), 30-45% of children in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan do not receive sufficient dairy products, and more than 40% consume insufficient amounts of fish figures that closely match our data [20]. According to the COSI programme (WHO Europe, 2022), the prevalence of fast-food consumption among schoolchildren in the European region ranges from 25% to 60% [21], which is comparable to the high indicators found among children in Namangan (41-76% depending on age).Parental nutritional literacy plays a particularly important role in ensuring appropriate dietary practices. In the course of our analysis, we also identified the following causes of dietary disturbances among children: (1) insufficient parental awareness regarding healthy nutrition; (2) approaches to feeding based on the principle of “simply to satisfy hunger,” without attention to nutritional quality.Our findings show that a significant proportion of parents acknowledge meal-regimen disturbances in their children, which is consistent with the conclusions of Chaput & Katzmarzyk, who found that parental nutritional knowledge directly determines the frequency of healthy or unhealthy food consumption in children [22]. Lack of dietary control in the family strengthens the influence of the external food environment (school, street, advertisements), which is a typical problem for countries of the region.The results obtained also confirm data from systematic reviews highlighting the importance of breakfast for cognitive development. According to Grantham-McGregor, regular and nutritionally balanced breakfast improves memory, attention, and academic performance [23]. However, in Namangan, up to 27% of children dislike breakfast, and the majority prefer simple carbohydrate-rich foods, which significantly reduces its effectiveness.The frequency of consumption of sweetened beverages and fast food identified in our study is of particular concern, as the WHO and WFP have repeatedly emphasized the association of these products with an increased risk of early obesity, metabolic disorders, and reduced academic performance in children [24].Thus, the results of the study are in agreement with international data and confirm the need for comprehensive interventions aimed at improving the quality of nutrition among schoolchildren in the region.

5. Conclusions

- The conducted study demonstrated that the structure of actual nutrition among primary school-aged children in Namangan significantly deviates from national and international standards of healthy nutrition. The analysis of dietary behavior revealed insufficient consumption of fish, dairy products, vegetables, and, in some cases, fruits, which creates prerequisites for deficiencies in protein, calcium, vitamin D, omega-3 fatty acids, and dietary fiber. At the same time, high intake of sweetened carbonated beverages, fast food, and confectionery products was observed, increasing the risk of obesity and metabolic disorders.This situation is consistent with international findings, indicating that the double burden of malnutrition a combination of micronutrient deficiency and excessive consumption of calories, fats, and sugars is increasingly identified among children in Central Asia and Europe. Comparison of our data with reports from WHO, UNICEF, and FAO shows that insufficient inclusion of dairy and fish products in children’s diets is a widespread problem across the region. A considerable proportion of parents acknowledge irregular eating patterns of their children, which highlights the importance of family factors and the need to improve nutritional literacy.The identified dietary disturbances negatively affect physical development, cognitive functions, immune resistance, and overall health of primary school-aged children. The most vulnerable are those whose diet is predominantly composed of high-calorie foods with poor nutrient density.The obtained results emphasize the necessity of comprehensive measures aimed at promoting healthy eating habits, raising parental awareness, improving the school food environment, and developing regional programs for the prevention of nutrient deficiencies and dietary disorders among children. In this regard, the following recommendations are proposed for organizing proper nutrition for primary school-aged children.I. For parents and families- Establish a consistent eating schedule for children, ensuring a mandatory nutritionally balanced breakfast.- Include milk and fermented dairy products, as well as fresh vegetables and fruits, in the daily diet.- Ensure regular consumption of fish (1-2 times per week).- Limit sweetened carbonated beverages, packaged juices, fast food, chips, and other ultra-processed food products.II. For educational institutions- Implement school breakfast programs in accordance with WHO and WFP recommendations.- Develop a standardized school menu with control over sugar, salt, and fat content.- Restrict the sale of unhealthy foods on school premises.- Improve nutritional literacy of teachers and families using WHO and UNICEF educational materials; organize and regularly conduct lessons focused on the development of healthy eating habits and nutrition culture among students and parents.III. For public health authorities- Conduct monitoring of the nutritional status of schoolchildren, including iron and vitamin D levels, as well as anthropometric indicators.- Implement preventive programs addressing deficiencies of vitamin D, iron, and calcium.- Develop regional measures to improve access to high-quality food products for low-income families.- Strengthen collaboration with educational institutions in promoting a healthy food environment.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML