-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Genetic Engineering

p-ISSN: 2167-7239 e-ISSN: 2167-7220

2025; 13(12): 289-295

doi:10.5923/j.ijge.20251312.03

Received: Nov. 9, 2025; Accepted: Nov. 27, 2025; Published: Dec. 9, 2025

The Importance of Indicators in Assessing Water Quality at Wastewater Treatment Plants (Uchtepa Wastewater Treatment Plant of the Jizzakh Suv Ta'minoti Joint-Stock Company)

Maftuna Mirzabekova1, Nargiza Eshmurodova2

1PhD Candidate, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2PhD in Biological Sciences, Associate Professor, Department of Ecological Monitoring, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Maftuna Mirzabekova, PhD Candidate, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

One of the fields that is rapidly developing worldwide is wastewater treatment processes. It is known that the initial period of wastewater treatment dates back to the 1800s, when the first facility for treating city wastewater was built in Scotland. Since then, this process has been widely applied around the world for the treatment of municipal and other types of wastewater. The basis of this process, in addition to the initial mechanical and physical purification stages, relies on the biological degradation of organic and pollutant substances with the help of bacterial consortia. In recent years, interest in using mixotrophic microalgae in wastewater treatment has increased. This is due to the ability of microalgae to efficiently utilize both organic and inorganic compounds for their growth. [1] The purpose of this review is to provide additional information about algae and to present data on the physical characteristics of the wastewater flowing into the Uchtepa wastewater treatment plant, which belongs to the “Jizzakh Water Supply” Joint Stock Company, as well as information about the microorganisms used for wastewater treatment and the microalgae found in the water composition. Microalgae currently play an essential role in wastewater treatment. Studies have shown that in biological purification processes of wastewater obtained from various sources, microalgae can utilize wastewater as a growth substrate, making them a promising, long-term, and cost-effective wastewater treatment technology. Microalgal biomass serves as an alternative means of removing nutrients and pollutants such as nitrogen compounds, heavy metals, and toxic chemicals. Wastewater treatment using microalgae is both economically efficient and practical—it not only provides renewable biomass but also represents an effective method of CO₂ fixation. Microalgae are rich in lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates, and after wastewater treatment, they can be used as value-added products and biomaterials.

Keywords: Water, Wastewater, Microalgae, Environmental, Biomass, Freshwater, Plankton, Pollution, Bacteria, Issue, Laboratory

Cite this paper: Maftuna Mirzabekova, Nargiza Eshmurodova, The Importance of Indicators in Assessing Water Quality at Wastewater Treatment Plants (Uchtepa Wastewater Treatment Plant of the Jizzakh Suv Ta'minoti Joint-Stock Company), International Journal of Genetic Engineering, Vol. 13 No. 12, 2025, pp. 289-295. doi: 10.5923/j.ijge.20251312.03.

1. Introduction

- During the past century, water pollution has become an increasingly pressing issue as a result of global urbanization and industrial expansion. Although 71% of the Earth’s surface is covered with water, human activities have led to the growing discharge of untreated waste into rivers and coastal waters, causing severe contamination of these aquatic ecosystems (Sonune and Ghate, 2004).According to forecasts, by 2030 global water scarcity will reach 40%, posing a serious challenge to both society and the economy. Despite the fact that the strategic importance of drinking water resources has never been as well understood as it is today, current water reserves face significant threats in terms of both quality and quantity. Issues of sustainable water management are now being raised in nearly all social, scientific, and political agendas. Furthermore, under current conditions, another crucial problem is meeting the increasing energy demand amidst the depletion of fossil fuel reserves and the expansion of various industrial sectors, while simultaneously minimizing the environmental impact of industrial waste.The vast amount of wastewater generated by municipal, agricultural, and industrial activities is also a major concern. For instance, when wastewater contains excessive amounts of nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen, it leads to eutrophication in lakes, disrupting aquatic ecosystems (Chandel et al., 2022). Since the mid-20th century, eutrophication has been recognized worldwide as a serious environmental issue. The annual per capita water availability dropped from 3,300 m³ in 1960 to 1,250 m³ in 1995 — a 60% decline, marking one of the lowest levels globally. By 2025, this figure is expected to decrease by another 50%, reaching around 650 m³ (Abdel-Raouf et al., 2012). Agriculture accounts for the largest share of water consumption (87%), while domestic and industrial uses account for approximately 7–8%, respectively (Samhan, 2008). [2]As carbon-fixing and biomass-producing organisms, algae are one of the three main groups of photosynthetic organisms inhabiting freshwater environments. They differ from higher plants (macrophytes) in terms of size and taxonomy, and from photosynthetic bacteria in terms of biochemical processes. Photosynthetic bacteria (unlike eukaryotic algae and cyanophytes) are strictly anaerobic and do not release oxygen during photosynthesis (Sigee, 2004).In freshwater bodies, the primary productivity of algae — that is, the amount of carbon fixed per unit of volume and time (mg C m⁻³ h⁻¹) — varies across environments. For example, the level of primary productivity in lakes differs significantly depending on trophic status and water depth:• Eutrophic lakes are characterized by high concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus, with very high productivity observed in surface waters. However, productivity decreases sharply with depth as algal biomass absorbs most of the light.• Mesotrophic and oligotrophic lakes, on the other hand, have lower overall productivity, but light penetration to deeper layers allows photosynthetic activity to continue even at greater depths.Although algae are primarily autotrophic (photosynthetic) organisms, some species have evolved secondary heterotrophic characteristics — meaning they can absorb complex organic compounds through their surface or actively ingest particulate matter. These organisms often resemble protozoa due to their lack of chlorophyll, high motility, and active uptake of organic substances, yet phylogenetically, they remain classified within the algal group. [3]Forms of Algae in Freshwater EcosystemsIn freshwater ecosystems, algae occur in two main forms:• as free-floating (planktonic) organisms, or• as attached (mainly benthic) organisms bound to a substrate.Planktonic algae move freely within the water column, and some species can actively regulate their position in the water. In contrast, attached algae are typically fixed in place or have very limited movement relative to the substrate. These benthic algae exist in a dynamic equilibrium with planktonic organisms. This balance depends primarily on two key factors:• Water depth, and• Water flow velocity.For phytoplankton populations to develop, the water flow must be low—otherwise, the current will wash them away—and sufficient light availability is also required. Consequently, planktonic algae dominate in the surface layers of lakes and in slow-flowing rivers.Benthic algae, on the other hand, require adequate light (i.e., shallow waters) but can tolerate higher flow velocities. Therefore, they tend to dominate over phytoplankton in fast-flowing rivers and streams. Benthic algae also need a suitable substrate for attachment—such as inorganic rocks, submerged plants, or aquatic vegetation growing along shorelines.The ecological distinction between planktonic and benthic (non-planktonic) algae is important, especially in sampling and quantifying algal populations.Planktonic AlgaePlanktonic algae dominate the main water mass of lakes and are particularly characteristic of temperate regions, where they exhibit seasonal succession of species. This succession depends on the trophic status of the lake.In eutrophic lakes, planktonic algae form dense blooms consisting mainly of diatoms, colonial cyanobacteria, and dinoflagellates during the later stages of the year.Taxonomic Differences — Main Groups of AlgaePlanktonic algae are often classified according to their size range:• Picoplankton — < 2 μm• Nanoplankton — 2–20 μm• Microplankton — 20–200 μm• Macroplankton — > 200 μmIn benthic environments (among substrate-attached algae), the size range is even broader—spanning from minute unicellular organisms that first colonize newly exposed surfaces to large filamentous algae that form part of the periphyton community. For example, attached algae such as Cladophora may have filaments extending several centimeters into the surrounding water. These macroscopic algae are often overgrown by small colonial or unicellular epiphytic algae. Thus, within a single microenvironment, algae can display an extremely wide spectrum of sizes.Morphological DiversityAlgal cells exhibit great variation in shape—ranging from simple, immobile spherical cells to large, multicellular structures.The most primitive form is a single, non-motile spherical cell. Over evolutionary time, this structure has become more complex through the development of flagella, changes in body shape, and the formation of elongated spines or projections. Cells may aggregate into small or large clusters without a distinct shape or form spherical colonies with a defined morphology. They may also form filamentous (thread-like) colonies, which can be either branched or unbranched.Motility is often associated with the presence of flagella, although some algae (e.g., the diatom Navicula and the cyanobacterium Oscillatoria) are capable of movement without flagella. This movement is achieved through the secretion of a surface mucilage layer. In many algae, the mucilaginous coating surrounding the cell or colony not only increases total volume but also plays an important role in maintaining shape and structural stability. [4]Algae as Photosynthetic MicroorganismsAlgae are photosynthetic microorganisms that grow by using sunlight and nutrients. However, large quantities of fertilizers are typically required for their cultivation. As an alternative to synthetic fertilizers, domestic, municipal, agricultural, industrial, and aquaculture wastewater can be utilized, as these are rich in organic and inorganic pollutants such as nitrogen and phosphorus.When algae are cultivated using waste or wastewater, biomass production occurs simultaneously with the removal of these pollutants from the aquatic environment. Thus, wastewater treatment is achieved through the elimination of contaminants.Compared to physical and chemical purification methods, algae-based treatment offers a more cost-effective and environmentally friendly way to remove nutrients, while also enabling resource recovery and recycling. However, to achieve sufficient nutrient removal, large-scale cultivation and harvesting of algal biomass are necessary. Unfortunately, large-scale biofuel production from algae is not yet commercially viable due to high production costs, making algal biofuel currently non-competitive in price.Nevertheless, integrating algal cultivation with wastewater treatment is among the most promising approaches for the economically feasible and environmentally sustainable production of biofuels and other bioproducts. This method significantly reduces the demand for large quantities of freshwater and nutrients required for algal growth. [3,4]

2. Materials and Methods

- This research was conducted to identify and analyze the algal composition, ecological significance, and bioindicator potential of microalgae found in wastewater samples collected from the Uchtepa District Wastewater Treatment Plant (Jizzakh region, Uzbekistan). The study was carried out between 2024 and 2025 in three main stages: sample collection, laboratory analysis, and data processing.Sample Collection. Water samples were collected in accordance with sanitary and ecological standards using sterile glass containers of 1 L capacity. Samples were taken from three main points of the treatment process — inlet (raw wastewater), biological treatment stage (aeration tanks), and outlet (treated water). All samples were transported to the laboratory at 4°C for immediate analysis.Algal Isolation and Identification. Collected samples were fixed with Lugol’s iodine solution and examined under a compound light microscope at 400× magnification using a Sedgwick–Rafter counting chamber. Morphological identification of algal taxa was performed based on the taxonomic keys of Prescott (1962), Komárek and Anagnostidis (1999–2005), and Nikitina (2005). [2,3,6]Identified species were classified into the following divisions: Cyanophyta (blue-green algae), Chlorophyta (green algae), Bacillariophyta (diatoms), and Euglenophyta (euglenoids).Physico-Chemical Analysis. Water temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD₅), nitrate (NO₃⁻), phosphate (PO₄³⁻), and ammonium (NH₄⁺) concentrations were determined following Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (APHA, 2017). These parameters were analyzed as key environmental factors influencing algal community structure. [9,11]

3. Result and Discussion

- At this point, let us focus on the Uchtepa Wastewater Treatment Plant, which operates under the “Jizzakh Suv Ta’minoti” Joint Stock Company.In accordance with the Resolution of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan No. PQ-3885 dated July 27, 2018, and the Order No. 22 approved by “O‘zsuvta’minot” Joint Stock Company on November 24, 2020, a new wastewater treatment plant has been constructed in the Uchtepa neighborhood (MFY) of Sharof Rashidov District, Jizzakh Region.The project, financed by the Asian Development Bank in the amount of USD 17,100,000, was implemented by the main contractor “Techcross Water and Energy Ins” over the period 2018–2024, with a designed capacity of 30,000 m³/day. The Uchtepa Wastewater Treatment Plant was commissioned in December 2024.Sewerage System and ConfigurationThe design capacity of the Uchtepa Wastewater Treatment Plant is 30,000 m³ per day.The facility treats wastewater that flows through the sewerage pipelines serving Jizzakh City, the A Industrial Zone, and the Uchtepa residential area of Sharof Rashidov District.The incoming wastewater is conveyed through the following collector pipelines:D-1000 mm: from Jizzakh City neighborhoods — Olmazor, Kimyogar, Zilol, Toshloq, Ko‘tarma, the city center (Markaz-2), and Qassoblik mahalla;D-1200 mm: from the A Industrial Zone collectors;D-350 mm: from Uchtepa, Toqchilik, Istiqlol, and Yangiobod neighborhoods of Sharof Rashidov District.Types of Sewerage SystemsA sewerage system is defined as a network designed to collect and convey wastewater—either combined or separately—to a treatment facility. In practice, the most common systems are:Combined sewer system (general flow),Separate sewer system, andPartially combined (mixed) system.Given that precipitation levels in Uzbekistan are generally low, the partially separated sewer system is most commonly applied. In this system, industrial and domestic wastewater is conveyed together to the treatment plant, while stormwater runoff is discharged into irrigation channels or natural water bodies.Wastewater Flow Parameters from the CityThe quantity of domestic wastewater discharged from a city or its district is determined by the following parameters:Average wastewater discharge:a) Daily flow rate: 30,000 m³/dayb) Hourly flow rate: 1,250 m³/hourc) Per second flow rate: 0.34 L/sMaximum wastewater discharge: a) Daily flow rate: 30,000 m³/day

| Figure 1. General construction design project |

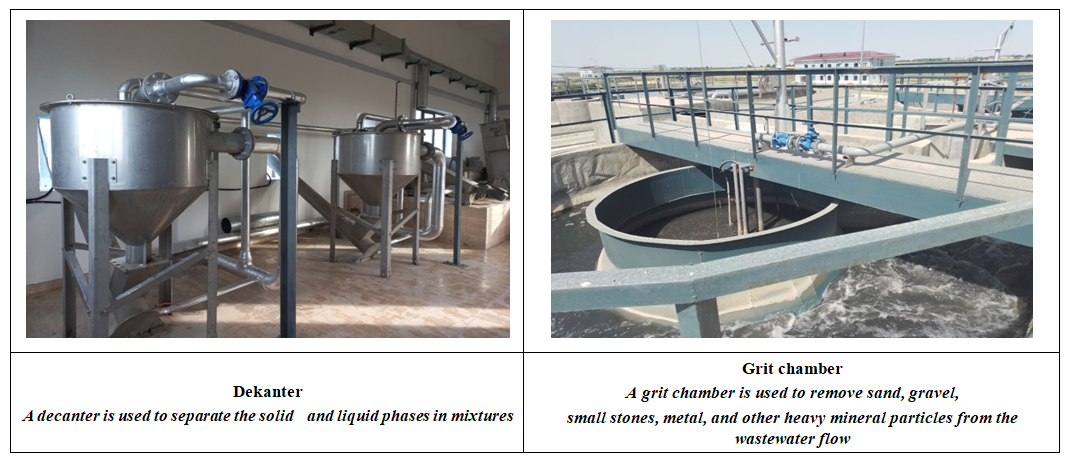

| Figure 2. Decanter |

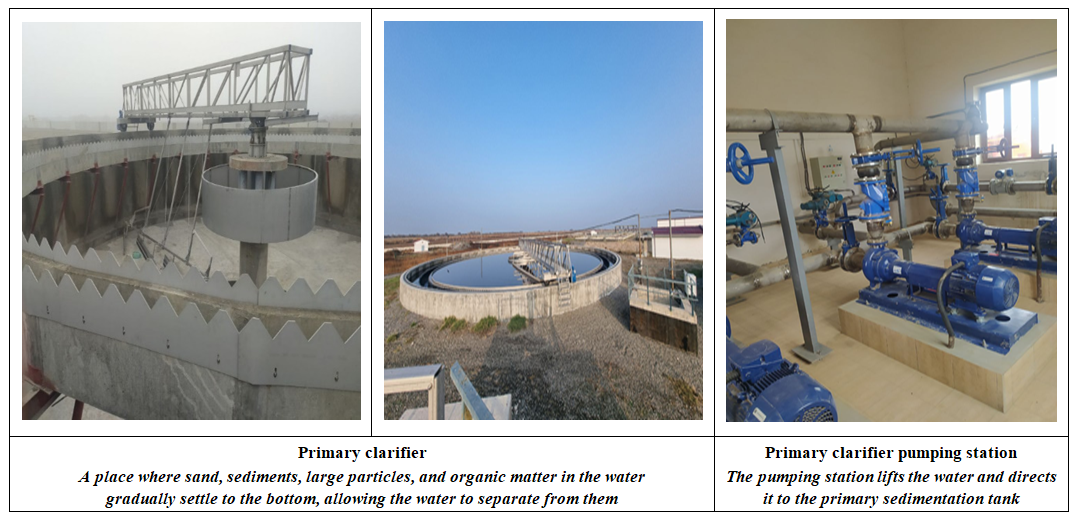

| Figure 3 |

| Figure 4 |

4. Conclusions

- The results of the conducted analyses show that wastewater represents an ecologically complex yet biologically active environment. The presence, diversity, and abundance of microalgae in such systems are directly related to the degree of water pollution. In particular, species such as Chlorella vulgaris, Scenedesmus quadricauda, Euglena viridis, and Navicula sp. are distinguished by their active growth at various stages of wastewater treatment.Algae are of great importance not only as bioindicators but also as effective agents of bioremediation. Through their cellular mechanisms, they absorb nitrogen, phosphorus, and heavy metal ions, accelerate the decomposition of organic compounds, and restore the oxygen balance in aquatic systems.The findings indicate that the use of algae in natural wastewater treatment systems is a sustainable, environmentally friendly, and economically efficient solution. Therefore, further research into the biotechnological potential of microalgae, their adaptation to local conditions, and the development of applicable implementation methods remain among the key scientific and practical priorities for the future. [8,14]

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML