-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2025; 14(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20251401.01

Received: Jun. 19, 2025; Accepted: Jul. 17, 2025; Published: Jul. 25, 2025

A Compendium of Select Commodity and Derivatives Market Scams

Dhanesh Kumar Khatri

Professor in Discipline of Management Studies, School of Management Studies (SOMS), Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), Maidan Garhi, New Delhi, India

Correspondence to: Dhanesh Kumar Khatri, Professor in Discipline of Management Studies, School of Management Studies (SOMS), Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), Maidan Garhi, New Delhi, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The paper discusses about two prominent cases - National Spot Exchange Scam of India and Nick Leeson Case (which lead to the closure of Barings Bank overnight). Apart from discussing the descriptive part of trading and settlement mechanism at National Spot Exchange, the paper presents the facts about volume of losses suffered in both the scams and how these two scams were unearthed. The technical aspect of both the scams is similar i.e. manipulation of the trades to gain undue profit, which can be accounted to lack of governance at the part of top management of both the organizations – National Spot Exchange and Barings Bank. The analysis of the two cases shows that during the period of these cases proper monitoring and operational risk management systems were not in place. Further, the authorities be at bank or exchange level were mainly focused about profits without caring for regulatory compliance. Further it is revealed that these two cases indicate that monitoring and surveillance were not in place, had such system of surveillance been in place the whistleblower would have cautioned about these kinds of lapses. Therefore, a concurrent audit and surveillance system is necessary for having a check on such incidences of scams in future. Despite of heavy losses for the investors and collapse of a bank overnight, the positive outcome of these two cases is that Government authorities and the regulators became alert and after these two incidences strict surveillance system is in place. Even the banks now have a system of creating mark-to-market provisions for their stock/commodity/currency market exposure.

Keywords: Spot transaction, Forward transaction, Derivatives transactions, Surveillance

Cite this paper: Dhanesh Kumar Khatri, A Compendium of Select Commodity and Derivatives Market Scams, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 14 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20251401.01.

Article Outline

1. Prelude

- Financial markets are the markets for money and monetary claims. These include money market, capital market, market for derivatives – futures and options, market for foreign currency. In these markets financial claims are traded with different objectives. Different traders in these markets are categorized into different categories on the basis of the objective with which the trader does the trading in these markets. A speculator has the objective to gain out of the price fluctuation, whereas a hedger has the objective to hedge – counter balance the risk of his earlier obligation/position in the underlying asset – share, bond, currency, commodity, and others. An arbitrageur is the one who does the trading in these markets to gain out of the price inefficiencies across different market. He takes a long position in the market where prices are low and simultaneously takes a short position in the market where prices are high. Although different traders have different objectives still every investor bears the risk – systematic and non-systematic while trading in these markets.While taking position the aim of the trader is to maximise the gain or minimize the loss, however sometimes either a silly mistake, greed for excessive profit or overconfidence of traders results into a scam leading to not only causing losses for the trader involved in scam but to all the investors/traders operating in the market. This poses a question mark on the surveillance system and efficiency of the regulators entrusted with the task of ensuring investor protection and integrity of financial system and financial market. The ensuing paper presents two such cases the first case is about National Spot Exchange and second is about how the greed of one single operator of derivatives market let to the closure of one of the strongest banks i.e. Barings Bank.

2. Scam One: National Spot Exchange Scam

In May 2005 Financial Technologies India Limited (FTIL) and National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India Limited (NAFED) jointly promoted National Spot Exchange Limited (NSEL) as a spot exchange for trading in commodities. In October 2008, NSEL started operations providing an electronic trading platform to willing participants for spot trading of commodities, the commodities included were bullion, agricultural produce, metals, etc. The trading on the exchange could be executed through the members of the exchange known as brokers of the exchange. The execution and settlement of the trades was as per the norms of NSEL. The prominent feature of NSEL was that it was a spot exchange with electronic trading facility which made it unique in the spot commodities market.

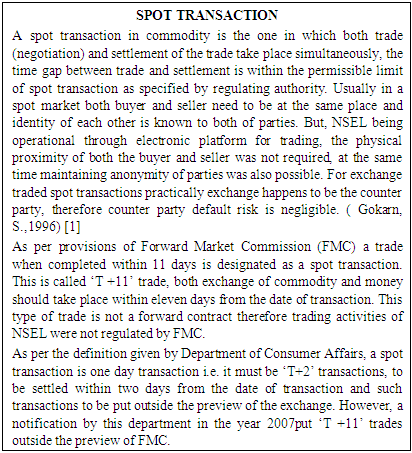

In May 2005 Financial Technologies India Limited (FTIL) and National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India Limited (NAFED) jointly promoted National Spot Exchange Limited (NSEL) as a spot exchange for trading in commodities. In October 2008, NSEL started operations providing an electronic trading platform to willing participants for spot trading of commodities, the commodities included were bullion, agricultural produce, metals, etc. The trading on the exchange could be executed through the members of the exchange known as brokers of the exchange. The execution and settlement of the trades was as per the norms of NSEL. The prominent feature of NSEL was that it was a spot exchange with electronic trading facility which made it unique in the spot commodities market.  The Mechanism of Trading and SettlementOn NSEL trading used to be conducted over the electronic platform by entering orders online through the trading platform of brokers. The automatic matching of the order would result into a trade as in the case of other exchanges. As anonymity of the parties is maintained therefore there must be some way of settlement of the trade. To facilitate the settlement NSEL made arrangement with several warehouses where one (seller) would deposit the commodity after quality certification and then sell the warehouse receipt through the electronic trading platform of NSEL. The trading and settlement at NSEL followed following stepsStep 1: Seller to deposit the commodity with designated warehouse after quality certification.Step 2: Seller can place a sale order with the broker; in turn the broker places the order in the online trading platform. (identity of seller is not disclosed on the trading platform)Step 3: Buyer places order to buy the commodity with the broker, in turn the broker places the order in the online trading platform. (identity of buyer is not disclosed on the trading platform)Step 4: Automatic matching of trades by the trading system and reporting of trades to respective trading members i.e. brokers. Step 5: For settlement purpose seller transfers the warehouse receipt to the buyer and the buyer makes the payment to the seller. If buyer wishes he can take the delivery from the warehouse, otherwise he can maintain the delivery in the warehouse by paying the rent of warehouse for post trade settlement period. If buyer maintains the delivery of commodity in the warehouse, then subsequently he can sell the same through electronic trading platform of NSEL.

The Mechanism of Trading and SettlementOn NSEL trading used to be conducted over the electronic platform by entering orders online through the trading platform of brokers. The automatic matching of the order would result into a trade as in the case of other exchanges. As anonymity of the parties is maintained therefore there must be some way of settlement of the trade. To facilitate the settlement NSEL made arrangement with several warehouses where one (seller) would deposit the commodity after quality certification and then sell the warehouse receipt through the electronic trading platform of NSEL. The trading and settlement at NSEL followed following stepsStep 1: Seller to deposit the commodity with designated warehouse after quality certification.Step 2: Seller can place a sale order with the broker; in turn the broker places the order in the online trading platform. (identity of seller is not disclosed on the trading platform)Step 3: Buyer places order to buy the commodity with the broker, in turn the broker places the order in the online trading platform. (identity of buyer is not disclosed on the trading platform)Step 4: Automatic matching of trades by the trading system and reporting of trades to respective trading members i.e. brokers. Step 5: For settlement purpose seller transfers the warehouse receipt to the buyer and the buyer makes the payment to the seller. If buyer wishes he can take the delivery from the warehouse, otherwise he can maintain the delivery in the warehouse by paying the rent of warehouse for post trade settlement period. If buyer maintains the delivery of commodity in the warehouse, then subsequently he can sell the same through electronic trading platform of NSEL. The Wrong Deeds Apart from allowing ‘T+2’ trades, NSEL also allowed forward trades, namely ‘T+25’ and ‘T+35’ trades. These had the provision for settlement after 25 days and 35 days from the date of transaction. Being forward trades, these should not have been allowed for execution on the trading portal of NSEL and none of the regulatory authorities objected to it and trading these unauthorized trades continued. Had this been alone then even not much losses would have been caused. Under the garb of these trades NSEL authorities allowed a combination of spot and forward trades like REPO (repurchase obligations in the money market). Practically, the clients were offered and forced to execute two trades on the same commodity with same parameters except the difference that one was a spot (T+2) transaction and another was a forward (T +25 or T+35) transaction, the difference in spot price and forward price was like interest earning for the spot buyer for providing funds in the form of payment of spot buying. (Chakrabarty. K, 2013) [2].Being online trading the anonymity of the parties was maintained therefore the actual credentials of the buyers and sellers could not be established and really the seller was either dummy entities or the farmers or agriculturalists who were expecting the yield from their respective crop in due course of time. This type of packaged deal (twin deal one spot and another forward) helped the seller of the spot transactions without having the physical quantity of the commodities sold at the same time warehouse authorities helped by issuing fake warehouse receipts without being supported by the physical stock. In practice the spot buyer was happy by receiving a difference in the forward price and spot price as interest for the payment made for spot purchase and further without having any hassle to take the physical possession of the commodities purchased. This mechanism was further complicated when directly or indirectly the buyers were prompted to roll the trades as soon as the maturity of forward trades arrived. The chain of twin set of transactions continued without any difficulty till the time a corresponding roll over was possible. In practice the spot buyers (forward seller) were the genuine investors or buyers lured to earn the interest from the difference in the spot and forward price and the spot sellers (forward buyers) were the same 24 parties either close associates of directors of the exchange or their relatives. Some of them were commodity planters and others were commodity traders. These 24 parties offered handsome return under the garb of twin set of transactions; by doing so they could get easy finance, even without the collateral of the commodity because they could manage fake warehouse receipt. It was the duty of NSEL officials to verify the stock of commodities with the warehouse but they simply ignored it. (Kumar, S. (2015).) [3]How the Scam was Unearthed Things would have continued without creating any payment crisis. In the beginning of 2013 two matters sparked helped in breaking the scam, i.e. (a) non-willingness of spot buyers for roll over, and (b) FMC order to cut the duration of forward transactions to a duration of 10 days. Both led to payment and settlement crisis at NSEL. The spot buyers wanted either the commodities or the payment in lieu of the commodities. Neither the funds were available as margins were not collected from the spot sellers, nor the commodities were available in the warehouse because of fake warehouse receipts produced by the spot sellers. The onus which lies on NSEL authorities for not verifying the physical stock with the warehouse and for allowing forward trades without being a forward exchange. Further NSEL authorities Namely Mr. Jignesh Shah, Mr. Joseph Massey and Mr. Shrikant Javalgekar repeatedly assured the clients and regulatory authorities that there is sufficient money in the investor protection fund say about Rs. 800 crores but there was only about Rs. 5 crores in investor protection fund. At the same time, they concealed the facts about warehouse capacities. The capacities of the warehouses were much less than the quantum of warehouse receipts issued by them. Journalist Sucheta Dalal, in an email dated May 8, 2012, revealed awareness of the fraudulent nature of NSEL contracts and the lack of safety in its operations. [4]The ResultThe ill-effect of this scam was severely reflected in a fast decline in the combined turnover of all the commodity exchanges by about 30 per cent to INR 125 Lakh Crore in 2013 from INR 175 Lakh Crore in corresponding previous year. [5]All this resulted in a scam of over Rs. 5,600 crore loss to commodity traders and investors. The procedure for the settlement of dues was being completed under the order and supervision of Honorable Supreme Court. According to the NSEL sources, the competent court-initiated recovery proceedings and passed a decree order of about INR 3,365 Crores out of INR 5,600 Crores against the defaulters. Additionally, the Enforcement Directorate also had attached assets worth approximately INR1740.59 Crores of the defaulters. [6]Further government defrauded money was recovered by the Enforcement Directorate (ED), which led to refund INR 1,220 crore (partial payment out of the total losses) to 13,000 investors who suffered the losses in NSEL fraud case. [7]In this case, 65 payouts were made by NSEL to investors through their respective brokers under the supervision of erstwhile Forward Markets Commission. A total of Rs.527.19 crore was distributed in 2013-14. The entire outstanding amount was paid to 608 investors whose investment was less than Rs.2 lakhs. Further, 50% of the outstanding amount was paid to 6445 investors whose investment was between Rs.2 lakhs and 10 lakhs. Furthermore, 5682 investors whose outstanding was more than Rs.10 lakhs were paid 6.5% of outstanding amount. [8]The Corporate Affairs Ministry of India passed an order to merge the NSEL with its promoting company namely Future Technologies India Limited, the order has been challenged by FTIL in the Supreme Court, and Honorable Supreme Court has ordered to maintain the status quo. The merger would practically mean that all the obligations of the NSEL to be settled by FTIL resulting a heavy loss for FTIL. [9]

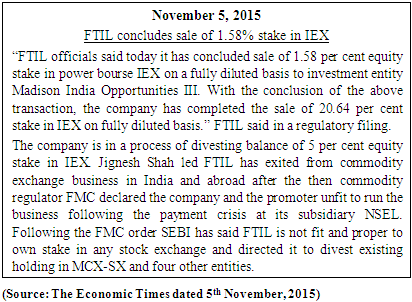

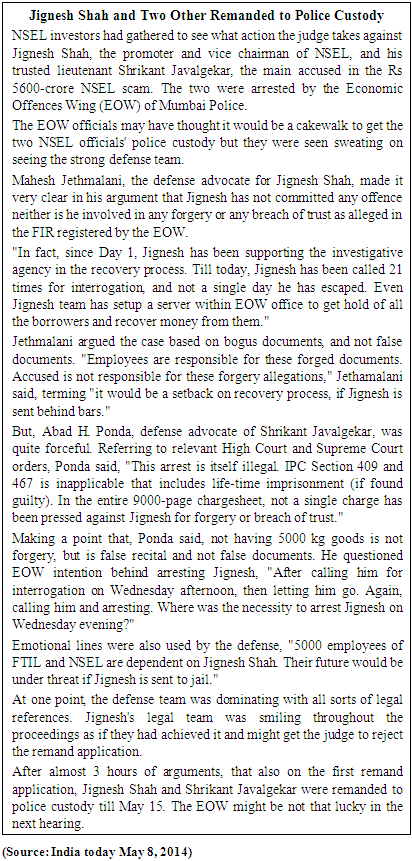

The Wrong Deeds Apart from allowing ‘T+2’ trades, NSEL also allowed forward trades, namely ‘T+25’ and ‘T+35’ trades. These had the provision for settlement after 25 days and 35 days from the date of transaction. Being forward trades, these should not have been allowed for execution on the trading portal of NSEL and none of the regulatory authorities objected to it and trading these unauthorized trades continued. Had this been alone then even not much losses would have been caused. Under the garb of these trades NSEL authorities allowed a combination of spot and forward trades like REPO (repurchase obligations in the money market). Practically, the clients were offered and forced to execute two trades on the same commodity with same parameters except the difference that one was a spot (T+2) transaction and another was a forward (T +25 or T+35) transaction, the difference in spot price and forward price was like interest earning for the spot buyer for providing funds in the form of payment of spot buying. (Chakrabarty. K, 2013) [2].Being online trading the anonymity of the parties was maintained therefore the actual credentials of the buyers and sellers could not be established and really the seller was either dummy entities or the farmers or agriculturalists who were expecting the yield from their respective crop in due course of time. This type of packaged deal (twin deal one spot and another forward) helped the seller of the spot transactions without having the physical quantity of the commodities sold at the same time warehouse authorities helped by issuing fake warehouse receipts without being supported by the physical stock. In practice the spot buyer was happy by receiving a difference in the forward price and spot price as interest for the payment made for spot purchase and further without having any hassle to take the physical possession of the commodities purchased. This mechanism was further complicated when directly or indirectly the buyers were prompted to roll the trades as soon as the maturity of forward trades arrived. The chain of twin set of transactions continued without any difficulty till the time a corresponding roll over was possible. In practice the spot buyers (forward seller) were the genuine investors or buyers lured to earn the interest from the difference in the spot and forward price and the spot sellers (forward buyers) were the same 24 parties either close associates of directors of the exchange or their relatives. Some of them were commodity planters and others were commodity traders. These 24 parties offered handsome return under the garb of twin set of transactions; by doing so they could get easy finance, even without the collateral of the commodity because they could manage fake warehouse receipt. It was the duty of NSEL officials to verify the stock of commodities with the warehouse but they simply ignored it. (Kumar, S. (2015).) [3]How the Scam was Unearthed Things would have continued without creating any payment crisis. In the beginning of 2013 two matters sparked helped in breaking the scam, i.e. (a) non-willingness of spot buyers for roll over, and (b) FMC order to cut the duration of forward transactions to a duration of 10 days. Both led to payment and settlement crisis at NSEL. The spot buyers wanted either the commodities or the payment in lieu of the commodities. Neither the funds were available as margins were not collected from the spot sellers, nor the commodities were available in the warehouse because of fake warehouse receipts produced by the spot sellers. The onus which lies on NSEL authorities for not verifying the physical stock with the warehouse and for allowing forward trades without being a forward exchange. Further NSEL authorities Namely Mr. Jignesh Shah, Mr. Joseph Massey and Mr. Shrikant Javalgekar repeatedly assured the clients and regulatory authorities that there is sufficient money in the investor protection fund say about Rs. 800 crores but there was only about Rs. 5 crores in investor protection fund. At the same time, they concealed the facts about warehouse capacities. The capacities of the warehouses were much less than the quantum of warehouse receipts issued by them. Journalist Sucheta Dalal, in an email dated May 8, 2012, revealed awareness of the fraudulent nature of NSEL contracts and the lack of safety in its operations. [4]The ResultThe ill-effect of this scam was severely reflected in a fast decline in the combined turnover of all the commodity exchanges by about 30 per cent to INR 125 Lakh Crore in 2013 from INR 175 Lakh Crore in corresponding previous year. [5]All this resulted in a scam of over Rs. 5,600 crore loss to commodity traders and investors. The procedure for the settlement of dues was being completed under the order and supervision of Honorable Supreme Court. According to the NSEL sources, the competent court-initiated recovery proceedings and passed a decree order of about INR 3,365 Crores out of INR 5,600 Crores against the defaulters. Additionally, the Enforcement Directorate also had attached assets worth approximately INR1740.59 Crores of the defaulters. [6]Further government defrauded money was recovered by the Enforcement Directorate (ED), which led to refund INR 1,220 crore (partial payment out of the total losses) to 13,000 investors who suffered the losses in NSEL fraud case. [7]In this case, 65 payouts were made by NSEL to investors through their respective brokers under the supervision of erstwhile Forward Markets Commission. A total of Rs.527.19 crore was distributed in 2013-14. The entire outstanding amount was paid to 608 investors whose investment was less than Rs.2 lakhs. Further, 50% of the outstanding amount was paid to 6445 investors whose investment was between Rs.2 lakhs and 10 lakhs. Furthermore, 5682 investors whose outstanding was more than Rs.10 lakhs were paid 6.5% of outstanding amount. [8]The Corporate Affairs Ministry of India passed an order to merge the NSEL with its promoting company namely Future Technologies India Limited, the order has been challenged by FTIL in the Supreme Court, and Honorable Supreme Court has ordered to maintain the status quo. The merger would practically mean that all the obligations of the NSEL to be settled by FTIL resulting a heavy loss for FTIL. [9]3. Scam Two: Nick Leeson Case

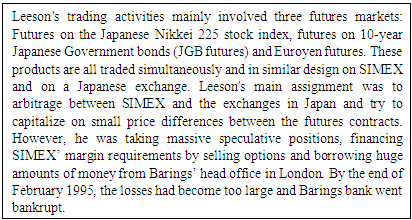

- In February of 1995, one man single-handedly bankrupted the bank that financed the Napoleonic Wars, Louisiana Purchase, and the Erie Canal. Founded in 1762, Barings Bank was Britain’s oldest merchant bank and Queen Elizabeth’s personal bank. Once a behemoth in the banking industry, Barings was brought to its knees by a rogue trader in a Singapore office. The trader, Nick Leeson, was employed by Barings to profit from low-risk arbitrage opportunities between derivatives contracts on the Singapore Mercantile Exchange and Japan’s Osaka Exchange. A scandal ensued when Leeson left a $1.4 billion hole in Barings’ balance sheet due to his unauthorized derivatives speculation, causing the 233-year-old bank’s demise. (Doiphode. R, 2014) [10].Nick Leeson grew up in London’s Watford suburb and worked for Morgan Stanley after graduating from university. Shortly after, Leeson joined Barings and was transferred to Jakarta, Indonesia to sort through a back-office mess involving £100 million of share certificates. Nick Leeson enhanced his reputation within Barings when he successfully rectified the situation in 10 months in 1992, after his initial success, Nick Leeson was transferred to Barings Securities in Singapore and was promoted to general manager, with the authority to hire traders and back-office staff. Leeson’s experience with trading was limited, but he took an exam that qualified him to trade on the Singapore Mercantile Exchange (SIMEX) alongside his traders. According to Risk Glossary:Leeson and his traders had authority to perform two types of trading:1. Transacting futures and options orders for clients or for other firms within the Barings organization, and2. Arbitraging price differences between Nikkei futures traded on the SIMEX and Japan’s Osaka exchange.Arbitrage is an inherently low risk strategy and was intended for Leeson and his team to garner a series of small profits, rather than spectacular gains.”As a general manager, Nick Leeson oversaw both trading and back-office functions, eliminating the necessary checks and balances usually found within trading organizations. In addition, Barings’ senior management came from a merchant banking background, causing them to underestimate the risks involved with trading, while not providing any individual who was directly responsible for monitoring Leeson’s trading activities. Aided by this lack of supervision, the 28-year-old Nick Leeson promptly started unauthorized speculation in Nikkei 225 stock index futures and Japanese government bonds.

These trades were outright trades or directional bets on the market. This highly leveraged strategy can provide fantastic gains or utterly devastating losses – a stark contrast to the relatively conservative arbitrage trading that Barings had intended for Leeson to pursue.Nick Leeson opened a secret trading account that was numbered “88888” to facilitate his surreptitious trading. He lost money from the beginning. Increasing his bets only made him lose more money. By the end of 1992, the 88888 account was under water by about GBP 2 Million. A year later, this had mushroomed to GBP 23 Million. By the end of 1994, Leeson’s 88888 account had lost a total of GBP 208 Million. Barings management remained blithely unaware. (Ramachandran, K.S.) [11].As a trader, Leeson had extremely bad luck. By mid-February 1995, he had accumulated an enormous position—half the open interest in the Nikkei future and 85% of the open interest in the JGB [Japanese Government Bond] future. The market was aware of this and probably traded against him. Prior to 1995, however, he just made consistently bad bets. The fact that he was so unlucky should not be too much of a surprise. If he had not been so misfortunate, we probably would not have ever heard of him. (Hirshliefer, David and Avanidhar Subhrahmanyan and Kent Daniel) [12].Betting on the recovery of the Japanese stock market, Nick Leeson suffered monumental losses as the market continued its descent. In January 1995, a powerful earthquake shook Japan, dropping the Nikkei 1000 points while pulling Barings even further into the red. As an inexperienced trader, Leeson frantically purchased even more Nikkei futures contracts in hopes of winning back the money that he had already lost. Most successful traders, however, are quick to admit their mistakes and cut their losing trades. (Niemeyer, Jonas) [13].How The Scam Was Unearthed Surprisingly, Nick Leeson effectively managed to avert suspicion from senior management through his silly use of account number 88888 for hiding losses, while he posted profits in other trading accounts. In 1994, Leeson fabricated £28.55 million in false profits, securing his reputation as a star trader and gaining bonuses for Barings’ employees. Despite the staggering secret losses, Leeson lived the life of a high roller, complete with a $9,000 per month apartment and earning a bonus of £130,000 on his salary of £50,000. On the other hand, he continued to hide and park the losses in dummy account 88888 he also concealed documents from bank’s auditors. By the beginning of 1995 losses accumulated to the tune of GBP 210 million in this dummy account, which was about half the capital of Barings Bank. Nick was really worried to cover these losses, and on January 16, 1995 Nick entered a high value trade of USD 7 billion betting on the fact that Nikkei would not fall anymore during overnight trades, but it was ill-fate of Nick an earthquake struck Kobe on January 16, 1995 and next day morning Nikkei price collapsed resulting into heavy losses in the trade executed by Nick. Nick’s losses mounted to a volume of USD 1.4 billion which was twice the Barings’ Capital. As the number of losses was very high therefore it could not be concealed in the dummy account 88888 and bank’s auditors noticed such a heavy loss, and the bank was finally forced to declare the bankruptcy. The Result The horrific losses accrued by Nick Leeson were due to his financial gambling as he placed his trades based upon his emotions rather than through taking calculated risks. After the collapse of Barings, a worldwide outrage ensued, decrying the use of derivatives. The truth, however, is that derivatives are only as dangerous as the Nick Leeson was placed on trial in Singapore and was convicted of fraud. He was sentenced to six and a half years in a Singaporean prison, where he contracted cancer. He survived his cancer, and, while imprisoned, wrote an autobiography called “Rogue Trader,” detailing his role in the Barings scandal. “Rogue Trader” was eventually made into a movie of the same name. Nick Leeson was released from prison in July 1999 for good behavior.Key Takeaways – How Such Scams Can Be Stopped The author suggests following measures to have a check on such incidences in future: I. The banks and exchanges must have operational risk assessment and management system acting like surveillance system.II. There should be robust internal control system to mitigate operational risk. III. Banks should have a system of mark-to-market losses provisioning system for their exposure in stock market, commodity market and foreign exchange market. IV. There should be independent whistleblower working in collaboration with internal control system to raise a forewarning of such incidences. V. There should be separate account of each client executing trades on the exchanges so that the surveillance department can track the volume of trades executed in one single account from the view point of price rigging. VI. Opening of separate account for each client linked with their PAN card or taxation card can help in having a check on ‘Benami’ (Benami transactions are the transactions in the name of third party without the consent and knowledge of the third party, such transactions are initiated by brokers and traders to conceal black money) transactions.

These trades were outright trades or directional bets on the market. This highly leveraged strategy can provide fantastic gains or utterly devastating losses – a stark contrast to the relatively conservative arbitrage trading that Barings had intended for Leeson to pursue.Nick Leeson opened a secret trading account that was numbered “88888” to facilitate his surreptitious trading. He lost money from the beginning. Increasing his bets only made him lose more money. By the end of 1992, the 88888 account was under water by about GBP 2 Million. A year later, this had mushroomed to GBP 23 Million. By the end of 1994, Leeson’s 88888 account had lost a total of GBP 208 Million. Barings management remained blithely unaware. (Ramachandran, K.S.) [11].As a trader, Leeson had extremely bad luck. By mid-February 1995, he had accumulated an enormous position—half the open interest in the Nikkei future and 85% of the open interest in the JGB [Japanese Government Bond] future. The market was aware of this and probably traded against him. Prior to 1995, however, he just made consistently bad bets. The fact that he was so unlucky should not be too much of a surprise. If he had not been so misfortunate, we probably would not have ever heard of him. (Hirshliefer, David and Avanidhar Subhrahmanyan and Kent Daniel) [12].Betting on the recovery of the Japanese stock market, Nick Leeson suffered monumental losses as the market continued its descent. In January 1995, a powerful earthquake shook Japan, dropping the Nikkei 1000 points while pulling Barings even further into the red. As an inexperienced trader, Leeson frantically purchased even more Nikkei futures contracts in hopes of winning back the money that he had already lost. Most successful traders, however, are quick to admit their mistakes and cut their losing trades. (Niemeyer, Jonas) [13].How The Scam Was Unearthed Surprisingly, Nick Leeson effectively managed to avert suspicion from senior management through his silly use of account number 88888 for hiding losses, while he posted profits in other trading accounts. In 1994, Leeson fabricated £28.55 million in false profits, securing his reputation as a star trader and gaining bonuses for Barings’ employees. Despite the staggering secret losses, Leeson lived the life of a high roller, complete with a $9,000 per month apartment and earning a bonus of £130,000 on his salary of £50,000. On the other hand, he continued to hide and park the losses in dummy account 88888 he also concealed documents from bank’s auditors. By the beginning of 1995 losses accumulated to the tune of GBP 210 million in this dummy account, which was about half the capital of Barings Bank. Nick was really worried to cover these losses, and on January 16, 1995 Nick entered a high value trade of USD 7 billion betting on the fact that Nikkei would not fall anymore during overnight trades, but it was ill-fate of Nick an earthquake struck Kobe on January 16, 1995 and next day morning Nikkei price collapsed resulting into heavy losses in the trade executed by Nick. Nick’s losses mounted to a volume of USD 1.4 billion which was twice the Barings’ Capital. As the number of losses was very high therefore it could not be concealed in the dummy account 88888 and bank’s auditors noticed such a heavy loss, and the bank was finally forced to declare the bankruptcy. The Result The horrific losses accrued by Nick Leeson were due to his financial gambling as he placed his trades based upon his emotions rather than through taking calculated risks. After the collapse of Barings, a worldwide outrage ensued, decrying the use of derivatives. The truth, however, is that derivatives are only as dangerous as the Nick Leeson was placed on trial in Singapore and was convicted of fraud. He was sentenced to six and a half years in a Singaporean prison, where he contracted cancer. He survived his cancer, and, while imprisoned, wrote an autobiography called “Rogue Trader,” detailing his role in the Barings scandal. “Rogue Trader” was eventually made into a movie of the same name. Nick Leeson was released from prison in July 1999 for good behavior.Key Takeaways – How Such Scams Can Be Stopped The author suggests following measures to have a check on such incidences in future: I. The banks and exchanges must have operational risk assessment and management system acting like surveillance system.II. There should be robust internal control system to mitigate operational risk. III. Banks should have a system of mark-to-market losses provisioning system for their exposure in stock market, commodity market and foreign exchange market. IV. There should be independent whistleblower working in collaboration with internal control system to raise a forewarning of such incidences. V. There should be separate account of each client executing trades on the exchanges so that the surveillance department can track the volume of trades executed in one single account from the view point of price rigging. VI. Opening of separate account for each client linked with their PAN card or taxation card can help in having a check on ‘Benami’ (Benami transactions are the transactions in the name of third party without the consent and knowledge of the third party, such transactions are initiated by brokers and traders to conceal black money) transactions. 4. Conclusions

- The technical aspect of both the scams is similar i.e. manipulation of the trades to gain undue profit, which can be accounted to lack of governance at the part of top management of both the organizations – National Spot Exchange and Barings Bank. The analysis of the two cases shows that during the time of these cases proper monitoring and operational risk management systems were not in place. Further, the authorities be at bank or exchange level were mainly focused about profits without caring for regulatory compliance. Further it is revealed that these two cases indicate that monitoring and surveillance were not in place, had such system of surveillance been in place the whistleblower would have cautioned about these kinds of lapses. Therefore, a concurrent audit and surveillance system is necessary for having a check on such incidences of scams in future. Despite of heavy losses for the investors and collapse of a bank overnight, the positive outcome of these two cases is that Government authorities and the regulators became alert and after this strict surveillance system is in place. Even the banks now have a system of creating mark-to-market provisions for their stock/commodity/currency market exposure.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML