-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2022; 11(2): 39-60

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20221102.02

Received: May 15, 2022; Accepted: May 29, 2022; Published: Jun. 13, 2022

A Review of Adopting IFRSs of the Libyan Oil and Gas Industry

Majdi Abushrenta

PhD. Student, Nottingham Business School, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, NG1 4FQ, UK

Correspondence to: Majdi Abushrenta, PhD. Student, Nottingham Business School, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, NG1 4FQ, UK.

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper discusses the evolution of accounting and explained the history of IFRS and the international organizations and their roles in IFRS acceptance. It presents the aspects related to adopting IFRS in developed nations, including the benefits and obstacles observed in the case of the developed countries that have embraced the IFRS. The paper explores how to improve understanding of the potential benefits and restrictions of IFRS adoption in developing countries; this study contributes to that knowledge by focusing on Libya's decision to use IFRS for extractive industries, which was previously unexplored. The study also tries to understand the internal and external variables driving the transition of sectors to IFRS. These factors are largely driven by coercive, normative, and mimetic pressures, as stated in this work's conceptual framework. The current review provided an overview of Libya's environment, considering the country's demographic political-economic aspects over the past few decades. The research found that, although a massive land with a relatively small population equipped with enormous oil and gas resources should expect the economy to thrive, we found the previous dictatorship, which dominated Libya for nearly 40 years, failed to improve the people's educational and professional standards due to mismanagement of the economy at the expense of some minor political victories. Furthermore, the accounting associations and unions established by the previous regime were highly politically minded and hence had no interest in enhancing the accounting standards and practices. Decades of their activities as the watchdog of the accounting profession, these associations failed to bring meaningful positive changes. Hence, accounting qualifications and training/education programmes were either weak or non-existence. In short, the entire economic activities in the country were highly politicised and had very little respect for the emancipation of professionals in the country.

Keywords: Adopting, International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), Oil and Gas, Libya

Cite this paper: Majdi Abushrenta, A Review of Adopting IFRSs of the Libyan Oil and Gas Industry, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 11 No. 2, 2022, pp. 39-60. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20221102.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) adopted rigorous and meticulous accounting standards in 2003 to overcome anomalies in accounting around the world. As a result, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) were developed, providing a straightforward set of accounting concepts. By the end of 2005, organisations operating in the European Union were required to use IFRS for financial reporting, with other developing countries following suit. This meant that IFRS adoption would automatically supersede the local standards (Almansour, 2019). Apart from its comprehensively, the IFRS adoption is deemed to offer standards that are easily understood and accepted by investment markets worldwide (Alsuhaibani, 2012). This means that not only does the IFRS bring comparability, but such principles also help improve transparency, hence making developing economies more attractive to international investors (Laga, 2013; Bischof and Daske, 2013; Elhouderi, 2014; Masoud, 2014). On the other hand, several factors have been identified by several studies which may undermine or delay the process of adoption of IFRS in developing countries. Factors such as cultural, political, and economic factors can cause difficulties in harmonising accounting standards (Tyral, Woodward and Rakhimbekova, 2007; Nurunnabi, 2017). Costs associated with adoption – redesigning, consultation, retraining - have also been regarded as challenging issues facing a large number of developing countries (Alsuhaibani, 2012; Elhouderi, 2014; Almansour, 2019). Last but not least, religion being a subset of environmental factors, has also been reported as one of the parameters that can impact the adoption of IFRS. Regarding the Arab countries, the presence of the Sharia Law, particularly those relating to riba and zakat, makes them incompatible with IFRS (Irvine, 2008; Alkhtani, 2010). The relevant theoretical framework for the choice of adoption of IFRS falls within the domain of the so-called new institutional theory (NIT), which advocates that the institutional pressures can play an important role in leading countries to adopt these standards (Irvine, 2008; Ibrahim, 2014; Nurunnabi, 2015). Thus, this study investigates the impact of enforcements from the institutions like the World Bank and accounting organisations using the lens of NIT in their role in adopting IFRS in the developing countries in the Middle East and North Africa and Libya. Furthermore, the purview of NIT is also used to investigate various internal components, which include administrative, legislative and cultural factors that can contribute to the possible challenges in adopting IFRS. A few studies have been conducted on the potential challenges and benefits of IFRS adoption in the context of Libya (Handley-Schachler, 2012; Elhouderi, 2014; Masoud, 2014; Zakari, 2014; Faraj and El-Firjani, 2014; Khaled; 2016 Binomran, 2021).Although the adoption of the IFRSs has been extensively investigated in developed economies (Masoud, 2014; Zakari, 2014; Bayoud, 2015), limited research on this topic has been conducted in developing economies (Laga, 2013; Faraj and El-Firjani, 2014). The problem of the study arises from the lack of IFRS adoption-based literature in the context of Libya.; even though the adoption of the international financial reporting standards has been investigated in developed economies extensively (Masoud, 2014, Zakari, 2014, Bayoud, 2015), limited research on this topic has been conducted on developing economies (Laga 2013, Faraj and El-Firjani, 2014). While more than 160 countries worldwide have already adopted IFRS, Libya still has not considered this. Libya is an example; it is a developing country with abundant oil and gas resources that focuses on direct foreign investment in these and other economic sectors. Previous similar studies have focused on the overall problems of adopting IFRSs in Libya, according to the literature. However, the benefits of Libyan firms adopting IFRS appear to have been under-researched and examined. As a result, a detailed examination of the Libyan situation, with an emphasis on the country's major economic sector, oil and gas, is critical. Furthermore, past studies did not focus on specific businesses and did not appear to employ a diverse enough set of data. As a result, the purpose of this research is to provide a clearer picture of the benefits and obstacles of adopting IFRS in the financial sector.In recent years, corporate financial reporting practices have been under development and changed worldwide, which are particularly significant in developing countries. Although there has been no agreement regarding using a unified accounting system for emerging economies, the adoption of International Financial Reporting standards was viewed as an appropriate accounting system that could enhance the growth of the economy in contexts. Therefore, there is an urgent need for emerging economies such as Libya to adopt and implement those standards (IFRS). In particular, the study aims to examine the feasibility of IFRS for the oil and gas industry by exploring the opportunities and challenges of this transition. In achieving the aim of the study, the following objectives must be met: To critically examine the national accounting practices and IFRS practices in Libya. Also, identify the benefits for the economy of adopting IFRS in one of the most important industries in Libya (oil and gas). The last aim is to identify the reasons for delaying the adoption of IFRS and the main factors affecting the adoption in Libya.

2. Overview of Accounting

2.1. Accounting History

- According to Edwards (1989), accounting as a profession has ancient roots in the Babylonian, Egyptian, Greek, Sumerian and Assyrian, civilisations. Krzywda, Bailey and Schroeder (1995) explained that the primary goal of accounting, in the beginning, was to keep accurate records of the owner's transactions so that they could maintain stewardship over their properties. Accounting was created in response to societal demands (Krzywda, Bailey and Schroeder, 1995). Charge/discharge accounts were the early names for accounting in the ancient world. In other words, the earlier societies needed to ensure accurate records of all products purchased and sold and expenses incurred (Jonsson, 1996). In the 14th century, Italian merchants considered charge/discharge accounts were considered inadequate for their sophisticated business activity with commercial branches in various regions of the world during the emergence of industrial Italy (Bribesh, 2006). As a result, there was an obvious necessity for the development of accounting systems and procedures. The introduction of double-entry bookkeeping demonstrated this need and has been dubbed the "foundation stone" for the transition of accountancy from the ancient to the contemporary age (Macye and Hoskin 1986; Edwards 1989; Carruthers and Espeland 1991).The goal of book-keeping, according to Luca Pacioli (Richard and Rambaud 2021), who produced the first debt and credit record in 1494, was to provide the trader with quick information about his assets & liabilities. Hence, Pacioli was dubbed the "founder of modern accounting" by other researchers (Pribowo et al. 2021). This bookkeeping system (double-entry bookkeeping) extended around the world after Pacioli’s book in the later centuries (Smith 2018). In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Industrial Revolution (IR) shaped modern accounting and its developments. The IR and the expansion of international trade expanded the number and size of organisations (Bribesh, 2006). The movement in the fundamental form of commercial organizations from individual ownership to limited stock companies encouraged this trend. Changes in ownership and the separation of ownership and management put a lot of pressure on accounting to deliver more information to a wide range of users interested in the company's operations. Several important reasons for the need to standardize accounting procedures, according to Das, Pramanik and Shil (2009) include international commerce growth, company internationalisation, increased international rivalry, and technological advancements in communication. The overall accounting framework should include standardizations and regulations to attain usefulness, dependability, and comparability. Bloom and Naciri (1989) believed that the standards of accounting were created to improve financial reporting comparability and uniformity. Furthermore, they suggested that mandating financial report uniformity incentivises data management and streamlines the process of drawing comparisons. Using a common standard also helps with alleviating the concerns of disclosure levels and guarantees homogeneity and saves costs for businesses (De George and Shivakumar, 2016). Irvine (2008) argues that the cost of changing and committing to standardised and transparent accounting practices if mandated can have detrimental financial implications for small and medium-sized businesses. Furthermore, the diversity of accounting practices is a consequence of several specifics such as legal environment, culture, and the economy's state (Nobes, 1998; Nobes, Parker and Parker, 2008). The standardisation of these practices could make them somewhat inefficient as they are no longer customised to the same ecosystem in which they are being employed. Accounting standards are intended to provide extensive direction on how to handle specific difficulties and areas where there is a lot of disagreement. Standardized accounting methods can assist businesses in recording and monitoring their actions and ensuring homogeneous, dependable, and accurate data. The Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) form the basis for most modern financial accounting systems (Cortese and Walton, 2018). Even though these principles incorporate several common assumptions, regulations, and rules, there are still variations in accounting standards across different countries. These standards are designed to meet local accounting objectives. Stakeholders ought to strive for the unification of accounting standards as it will help compare the financial figures generated by different companies; this will guide in making good investment decisions based on the multinational companies' cross-border activities and the listing of companies of various nationalities on other stock markets.

2.2. The Development of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS)

- Most companies used to prepare their financial statements locally, using the old accounting systems that were customary in their nations. However, the world has recently witnessed a huge movement towards globalisation, with cross-border trade now outpacing local activity levels. As a result, standard accounting systems, originally built to manage local data, cannot process the financial data generated between countries (Zehri and Chouaibi, 2013; Montani et al., 2021). This development necessitated the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) proposal to unify the principles of accounting (Shil, Das and Pramanik, 2009). The next section will go through the history of these standards and the organizations that assisted in their development.

2.2.1. A Brief History of IFRS

- Regarding IFRS development, the significant differences between local accounting standards across nations necessitate the creation of a unified set of international the principles of accounting that will address the comparability issue that arises when comparing financial reports across countries, particularly for countries that rely on other countries, international organizations, or stock markets for capital (Ali, 2005). Following this, the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASSC) 1971 issued the first set of International Accounting Standards (IAS) (De George, Li and Shivakumar, 2016). The IASC issued around 40 International Accounting Standards. Later in 1977, a new group called the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) was established to help the ISAC by persuading IFAC member countries to embrace IAS, since almost all of the IASC members were also IFAC members (Sawani, 2009). The IFAC was created in 1977, and it collaborated with the IASC to release various statements related to international accounting standards. Many nations implemented standardised accounting practices to improve the quality of their financial accounts after the Asian crisis of 1997 (Outa, 2013). The IASs were endorsed by the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) in 1998 as a single set of IAS to improve the quality of financial reports. In addition, Hamidah (2013) claim that most of the early adopters of IFRS were a part of and actively involved in international bodies, such as the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), the International Financial Accounting Standards Board (IFASB), and the G-20 group of countries. the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) took over the IASC and issued the IFRS to improve the overall quality of financial reports across nations. Between 2001 and 2004, the IASB tasked a committee of experts with improving the quality of international accounting standards to improve their universal acceptability. The European Commission came up with legislation in 2002 mandating companies registered on EU stock exchanges to implement the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) beginning in 2005 (Othman and Kossentini, 2015; Nurunnabi, 2021). Furthermore, to satisfy the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and bring IFRS in line with US GAAP, the IASB and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) reached an agreement in 2002. But despite the improved collaboration between the IASB, FASB, and SEC, much work has to be done to produce new accounting standards that satisfy all parties. However, the (SEC) repealed the financial statements on harmonisation prepared under IFRS and US GAAP for international companies listed on US stock exchanges in 2007 (Tan et al., 2016). Furthermore, the 2007-2008 Financial Crisis had little impact on many nations’ adoption of the IFRS. Despite this, the IASB has been under intense pressure from various groups to raise the international standards on auditing (ISAs) to compromise the impact of any future financial crisis (Mala and Chand, 2012). Furthermore, there were constrained on the business profit during the 2008 Financial Crisis for nations that had not yet embraced the IFRS and non those implementing the IFRS during the crisis. Nonetheless, both adopters and non-adopters of the IFRS saw significant improvements in earning quality following the global financial crisis (Slaheddine and Fakhfakh, 2017). While, the Financial Crisis may have resulted in some financial ratios, such as profitability and liquidity ratios, being reduced for countries that have already adopted the IFRS during the financial crisis, there was a rapid return on confidence in financial information after the crisis due to increased transparency in financial reports; this, in turn, improved the stability of stock markets (Abu Alrub et al., 2020; Frey and Chandler, 2006). The new IASB structure has also seen much criticism despite its acceptance by the American authorities as it was first rejected (Oliverio, 2000) in the European region. As per Buchanan (2003), the US stritowardards hold leverage and control on the IFRS, thereby raising questions regarding the suitability of these standards for developing markets.

2.2.2. International Organisations' Role in IFRS Adoption

- Various global organisations worked with the IASC to enforce the adoption of the IFRS, particularly among companies registered on stock exchanges. The IOSCO, IFAC, OECD, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the European Union are among these international organizations that collaborated to achieve this aim (Lasmin, 2012; Triyuwono et al., 2015; Rodrigues and Craig, 2007). As a result of the partnership between the IASB and other international organizations, such as the G20, IOSCO, and IFAC, IFRS adoption has significantly increased (Whittington, 2005). For instance, the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) mandated that all companies in IOSCO member nations implement the IFRS (Triyuwono et al., 2015). Due to the efforts exerted by the Worldwide Organization of Securities Commissions, the adoption of IFRS by international stock markets has expanded dramatically, intending to improve the integrity of information on finance offered by corporations registered on global stock markets (Lasmin, 2012). Nevertheless, there are significant disagreements between some national and international accounting principles. Consequently, the IASC and IOSCO must give more accounting information to both foreign and local investors. Moreover, such information must be relevant to the application of the IASs to help them understand the financial reports prepared in conformity with the IFRS (Adams et al., 1993).The EU decided in 2002 to make IFRS mandatory beginning in 2005 to strengthen its validity and boost financial reporting consistency among European countries (Koning, Mertens and Roosenboom, 2018). Due to the pressures exerted by the EU, many European countries have adopted the IFRS to strengthen the EU's institutional credibility. As a result, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows into accepted countries have increased significantly since the EU required them to implement the IFRS in 2005. This is because the implementation of IFRS has increased the comparability and openness of financial accounts, attracting more overseas investors (Lasmin, 2012).Furthermore, the World Bank and the IMF have played a crucial role in urging many countries to adopt the IFRS, particularly those seeking financial aid from these bodies (Traistaru, 2014; Pricope, 2015; Hasan et al., 2008). Consequently, these international bodies have played a key role in pushing developing nations to adopt IFRS by highlighting the benefits pertinent financial performance and stronger stock exchanges in these financially restricted markets. This is specifically for countries seeking financial help from these bodies to solve their financial and economic problems (Thompson, 2016).Furthermore, the adoption of IFRS has been driven by the IFAC's pressures, which have prompted several IFAC member nations to integrate IFRS into their domestic accounting standards (Ali, 2005; Alsuhaibani, 2012). Furthermore, the IFAC backed up the IASB's work by establishing standards for using the IFRS in practice and promoting the global accounting profession. However, IFAC membership was limited to countries with at least one professional accounting association (Mwaura and Nyaboga, 2009). Following the demand from professional accounting organizations, several developing countries have embraced the IFRS to enhance the financial statement's quality (Pricope, 2015) and emulate other successful accounting organizations to obtain greater institutional credibility (Hassan, Rankin and Lu, 2014; Hassan, 2008).The IASB has since 2002 agreed with the US standards-setting authorities, such as the SEC and the FASB, to issue financial statements that meet quality standards and are based on the IAS (Camfferman and Zeff, 2018). The US is yet to embrace the IFRS although it controls many international organizations. That is to keep its power to rule these institutions, which can promote its interests (Thompson, 2016). IFRS adoption by the EU was easier than in the US, despite the US having an Anglo-American culture and an English common legal origin. The US believes that IFRS adoption is unnecessary for US companies because it encourages many countries to prepare their financial reports using the US GAAP, but not the other way around (Eroglu, 2017). However, one idea of accounting regulation that appears to be overlooked in contemporary IFRS literature is that IFRS is not static (Trimble, 2017). The IASB is constantly developing and amending the IFRS at the time of this study. Before embarking on a project to produce new IFRS Standards or major revisions to existing IFRS Standards, the Board conducts a research effort to gather evidence regarding the problem to be solved and determine whether a suitable solution can be found. The Board may advance research to standard-setting to create a new Standard or significantly change an existing one (IFRS plan, 2021). The current schedule of the ongoing projects and programs considered by the Board is in Appendix 1. Furthermore, since 2002, efforts to align principles-based standards with U.S. GAAP have eliminated several of the standard's alternate reporting alternatives and increased transparency requirements such as revenue recognition criteria. As a result, IFRS adoption is not easy even over time as it can be concluded from comparing the pre-and post-reporting quality. According to Capkun, Collins and Jeanjean (2012), excessive adjustments to IFRS were made between 2003 and 2005, reflecting an increase in the standards' flexibility. The authors listed 18 amendments to IFRS, including permitting the capitalisation of restoration andre vValcharges for Properties, Plant, and Equipment (PP&E). They also point out that six new standards were issued over that period, with the first one taking effect in 2005. As a result, research examining IFRS adoption before 2005 compared standards vastly different from those focusing on 2005 and later adoptions. Special attention is paid to the IFRS 6 oil and gas standard which is described in the upcoming section.

2.2.3. Accounting Practises in the Extractive Industries IFRS 6

- The accounting practises in the extractive industries involved with the exploration and evaluation of mineral resources are attempted to be harmonised by IFRS 6 issued in 2004 (Cortese and Irvine, 2010). It is worth emphasising that this standard covers the expenditure of the activities pertinent to the exploration and evaluation (E&E) phase (Abdo, 2016). The expenses of the activities in the pre and post E&E stages are not covered (Abdo, 2016). The point of start for IFRS6 is marked by the legal permissions for explorations and extends till the conclusion on the commercial feasibility of the extraction of mineral. The expenditure of an E&E asset under the IFRS 6 is measured and recognised by selecting an accounting policy applied consistently throughout the process. The pre-E&E activities associated with the exploration of mineral reserves can be accounted for in two ways based on the successful viability of explored minerals (Abdo, 2016). The first approach is similar to the Successful Effort (SE) method, predominantly applied for situations in which the exploration phase leads to unsuccessful or commercially non-viable mineral reserves. In this case, pre-E&E activities cannot be tagged to any pertinent mineral reserves and, therefore, are written off. On the other hand, if the exploration phase yields an E&E asset, pre-E&E activities can be expended on this E&E asset, and therefore, a revaluation model can be adopted for these assets (Abdo, 2016). Consistent classification of assets as tangibles and intangible is required for accounting policy implementation purposes. Furthermore, IFRS6 mandates the disclosure of information pertinent to E&E assets, including accounting policy choices, income, expenses and operating cash flows (Abdo, 2016). Furthermore, the political underpinnings associated with the adoption of IFRS 6 were explored by Noel, Ayayi and Blum (2010) from an ethical standpoint. The authors concluded deviation from the discourse ethics in the operation of IASB.Cortese et al., (2009) found that extractive industries used economic concerns to set favourable accounting methods and financial reporting standards. Oil and gas industries primarily employed two methods for accounting principles viz. successful efforts (SE) and full costs (FC). Authors pointed out that despite efforts to harmonise these accounting practices, legal and regulatory oversight has been minimal, leaving a flexible accounting practice as a reporting norm. Cortese, Irvine and Kaidonis (2010) further discussed the overlapping interests and connections implicated in setting the IFRS for the extractive industries throughout their research. It was found that parts of authoritative extractive industries have apprehended the regulatory process of setting IFRS 6. Using critical discourse analysis, the authors concluded that the existing accounting practises of the sector were rearranged and codified as part of adopting IFRS 6. This observation is in line with the deductions of Gallhofer et al., (2011) on the adoption of IFRS 6 as means to flexible accounting guidelines for reporting. Consequently, the authors concluded the role of IFRS 6 to legitimise existing accounting practices instead of aiding transparent reporting that could enable various stakeholders to compare the entities and make informed financial decisions. Cherti and Zaam (2016) studied three petroleum companies’ financial and account statements under IFRS and deduced that the adoption had a positive impact on financial and accounting information quality as compared to the financial and accounting information under the national GAAP. Therefore, as IFRS adoption is observed to be useful in the petroleum sector, it is possible to positively impact Libya's oil and gas sector, where many opportunities are waiting for the Libyan oil and gas sector to take the IFRSs system in their accountancy standard. IFRS have been implemented or approved in 144 countries worldwide, including some of the world's most powerful nations (such as the EU member states and Australia) (IFRS, 2018). Moreover, several large organizations have accepted these guidelines, especially those listed in the capital market, international banks, global development agencies, professional accountants, and politicians (Botzem and Quack, 2009; Botzem, 2012).

3. Literature Review

3.1. IFRS Adoption in Developed Countries

- Despite the widespread acceptance of IFRS, Zehri and Abdelbaki (2013) believed that IFRS are better suited to developed countries, stating that the first edition of IAS/IFRS was primarily designed for developed countries. Furthermore, the IASB's board members come from only nine countries, five from the US and the EU, with the remaining members coming from South Africa, Canada, China, and Japan (Chandra, 2011). Whittington (2005) highlighted that the IASC has pushed for IFRS adoption by developed economies since its inception in 1973, especially in 1995. As a result, the International Organization of Securities Regulators adopted the set of standards designed by the IASC for use by their members in 2000. Most international stock exchanges currently accept IFRS for foreign entrants; however, in the United States, they are permitted, but accounting must also conform with GAAP. According to Whittington (2005), many countries develop local accounting standards using international norms as a foundation; those that have none already are planning to require or enable IFRSs for listed firms soon (IFRS, 2018).

3.1.1. IFRS Adoption and European Union (EU)

- The EU commission finally acknowledged the inadequacy of the financial statement directives in 1995 and launched efforts to achieve better international standardisation, both inside and beyond the EU. Since that time, the EU has emphasised IASB standards by EU businesses (Walton and Aerts, 2009). The Commission, in 1999, recognized the practicality and benefits of increased international harmonisation and concluded that the IFRS looked to be the best appropriate standard for worldwide financial reporting demands (Yu, 2006). The Commission called for more harmonisation in accounting and that all EU companies should submit consolidated financial reports following IFRS (Walton and Aerts, 2009; Whittington, 2005). In 2001 and 2003, the EU updated its 4th and 7th directives to correspond more with IAS 39 to encourage cooperation and reduce inconsistencies between IFRSs and EU directives (Walton and Aerts, 2009). All publicly traded firms in the EU are since January 2005 IFRS complaints in preparing financial statements (Irvine, 2008). The implementation of the IFRS, both mandatory and optional, has sparked a flurry of research in industrialised countries (De George et al., 2016). The study by Leuz and Verrechia (2000) looked at the accounting decisions made by German companies listed in the German stock index in 1998. The authors show that an organisation's financing needs, and size play a role in embracing international standards.Affes and Callimaci (2007), for their part, have underlined the motives behind the German and Austrian listed companies' early adoption of IAS/IFRS. The likelihood of early adoption of IAS/IFRS improves with firm size, according to a logistic regression done on a sample of 106 German and Austrian firms. On the other hand, the relationship between anticipated IAS/IFRS adoption and debt seems inconsequential to highly leveraged enterprises as their creditors may seek debt covenant compliance based on specific calculations. Furthermore, Dumontier and Raffournier (1998) found no significant association between debt ratio, voluntary adoption of IAS, and company performance in a sample of 28 companies listed on the Swiss stock exchange. Even though this would further the argument on IFRS adoption, the comparison between countries is not considered in this work. The next section will focus on some existing challenges and opportunities associated with adopting IFRS.

3.1.2. Benefits and Challenges of IFRS Adoption in the Developed Countries

- The utilisation of a uniform accounting system worldwide makes it easier to analyse financial accounts from different countries and compare them more efficiently (Choi and Levich, 1991). As a result, the reports of numerous companies can be examined by potential investors to determine where to invest in such a time of commercial globalisation (Larson, 1993). In addition, a unified accounting system will make it easier to move cash and other resources between nations and bring down the cost of preparing financial reporting (Tyrrell).Australia and the European Union were among the first developed countries to comply with the IFRS standards. The establishment of the IFRS aims to minimise irregularity (Agostino et al., 2010) in accounting information and garner the confidence of investors (Tarca, Morris and Moy, 2013; Florou and Pope, 2012). However, several issues are to be concerned about, including IFRS (endorsement, translation, interpretation, implementation costs), a lack of continued education and training, active lobbying, and various enforcement methods (Hellmann, Perera and Patel, 2010). Following the implementation of IFRS, the UK developed its accounting quality, resulting in enhancing accounting statements (Tsoligkas and Tsalavoutas, 2011; Latridis, 2010). Nonetheless, IFRS hasn't had a similar influence in Poland, since they haven't had a big impact on value relevance (Dobija and Klimczak, 2010). Furthermore, according to Callao, Jarne and Lainez (2007), early indicators in Spain imply that the value relevance of accounting data has not improved much due to IFRS. This is significant because it implies that each country's local accounting enforcement, when combined with IFRS values, has a detrimental impact on the comparability of financial statements and IFRS implementation.In a study of 13 IFRS-adopting countries, it was discovered that 11 were still using native GAAP; companies in IFRS-adopting countries reported a greater increase in trading volume and return volatility than companies in non-IFRS-adopting countries (Landsman et al., 2012). Nonetheless, the main incentive for transitioning to a single set of standards has been the ability to compare financial reports across countries under IFRS. It is expected that convergence to IFRS rather than domestic GAAP can improve the comparability of the financial report and benefit global investors. IFRS harmonisation offers superior accrual quality than local GAAP, according to two stage research findings throughout 13 nations as well as 20 industries (Aubert and Grudnitski, 2011). While the effects of voluntary and forced adoption of IFRS varied significantly, the average liquidity and capital cost remain unchanged. In contrast, liquidity grows, and capital cost decreases in the latter case (Daske et al., 2013). According to the study, IFRS adoption did not develop profit comparability across Europe regarding cash flow and accruals immediately. They also believe that harmonisation of accounting is un effective in learning from inter-firm comparisons as IFRS adopters to experience immediate improvement in their context (Lang et al., 2010). Foreign investment in IFRS enterprises, on the other hand, has increased; this may not have occurred in the absence of greater comparability between these firms (DeFond, Hu, Hung and Li, 2011).It was observed that mandatory application of the International Financial Reporting Standards boosted the information quality in capital markets in 46 countries between 2001 and 2007. Companies in the same jurisdiction adopting IFRS lose some of their comparability with their domestic counterparts (reporting under GAAP) once IFRS is implemented (Cascino and Gassen, 2015). In addition, after the adoption of IFRS, book values in France and Germany are less comparable because of the variety of accounting options available (Liao et al., 2012 For the first time, the French enterprise’s adoption of represented evidence of the enhancement of quality in financial statements. Thus, IFRS equity adjustments, which are voluntary, had a value relevance dependent on the information release (Cormier et al., 2009). A study conducted by Devalle et al., (2010) in France, Italy, the United Kingdom, and German represented the growing evidence of the value and importance of book value and information content on earnings after implementing IFRS (Agostino et al., 2010). Another study by Manganaris t al., (2015) found the coexistence of lower conservatism with higher-value accounting information among 15 European nations before & after mandatory IFRS implementation. According to studies, the adoption of IFRS has been linked to a reduction in equity costs (Li, 2010). On the same lines, in Germany, businesses that are dominated by significant public debt and are seeking foreign financing are likely to embrace IFRS (Tarca et al., 2013) to have more options. However, the influence has been felt in debt finance as well. With robust enforcement, mandated IFRS adoption has a good economic outcome for corporate debt financing, particularly bond and loan financing (Florou and Kosi, 2015; Chan, Hsu and Lee, 2015; Moscariello, Skerratt and Pizzo, 2014). The study by Li (2015) noted that the IFRS adoption reduces the capital cost and the level of conditional conservatism in countries with robust enforcement. To compare the cost of transition, Taylor (2009) studied 150 public businesses in their first year of adopting IFRS IN the UK, Singapore and Hong Kong. According to the findings, the adjustment cost for businesses in the United Kingdom was higher than for companies in Hong Kong and Singapore. In a similar study of the cost associated with the implementation of IFRS, Fox et al. (2013) found that the costs of implementing the standards in the Republic of Ireland, the UK, and Italy were higher than the reporting benefits under IFRS. Recent studies on various nations outside the EU that have implemented IFRS reveal diverse effects depending on the countries' peculiarities. In certain countries, using IFRS has shown better quality in financial reporting and reduced the levels of earnings management for companies (Ji and Lu, 2014; Cai, Rahman and Courtenay, 2008), whereas in others, IFRS has failed to improve the accounting data quality outside the EU (Ji and Lu, 2014; Cai et al., 2008; Khanagha, 2011). Furthermore, IFRS adoption will decrease the cost and time associated with releasing new standards in emerging nations; it will enhance stock market efficiency and make financial reporting more understandable. (Asharf and Ghani, 2005).

3.2. Challenges of IFRS Adoption in the Developing Countries

- Generally, developing nations are currently in the early phases of economic growth and lack a stable source of income (World Bank 2019). IFRS has gotten huge attention among developing countries; some developing countries adopted IFRS fully or partially, whereas others have yet to do so, such as Libya. Although various issues may affect country specificities and period, it is agreed among the researchers that the countries’ environmental conditions play a paramount role in the decision of developing nations to adopt or not to adopt IFRS (Othman and Kossentini, 2015; Shima and Yang, 2012; Judge, Li and Pinsker, 2010; Bogdan et al., 2010; Clements, Neill and Stovall., 2010; Zeghal and Mhedhbi, 2006; Hope, Jin and Kang, 2006). Several scholars have questioned the relevance of IFRS to developing countries; while some consider it vital to economic development (Cairns, 1990; Larson, 1993), others think that the IASB is only interested in the economies of the West (who are the major IFRS adopters) and ignores the needs of the developing nations (Alkhtani, 2012; Alsulami and Herath, 2017).Many developing countries employ the IFRS as one of their standard-setting tactics (Perera and Baydoun, 2007). On the other hand, Hassan et al. (2014) considered the Middle Eastern region’s adoption of IFRS as a bigger effort to safeguard the confidence of investors and reform accounting governance. Hassan et al., 2014 warned that if it is not done well, its risks may be perceived as purely symbolic. According to Aghimien (2016), progress toward IFR complaints could provide reliable financial information by improving transparency and thereby, foster investment in Arab countries. However, for some nations, such as Iran, the emphasis on transparency can be troublesome as the disclosure requirements may be culturally unacceptable (Rostami and Hasanzadeh, 2016). According to Irvine (2008), adopting a transnational set of accounting standards, such as IFRS, confers legitimacy to emerging economies, improves information quality between countries, and encourages cross-border investment. In contrast, a single set accounting standard as IFRS might not provide other controls' due to differing political, economic, social, and cultural features. Abd-Elsalam and Weetman (2003) showed that the concept of international accounting standards encompasses extremely distinct cultural norms, the study revealed that Egyptian businesses had had a tough time transitioning to IFRS.Some countries Pakistan, Thailand, Bangladesh, Nigeria and the Arab Gulf Countries Co-operation Council (GCC) rely on local GAAPS alongside the IFRS, while others, such as Zimbabwe and Iran, demand the legislative consistency of IFRS with legal structure (Mashayekhi and Mashayekhi, 2008; Chamisa, 2000; Faraj and El-Firjani, 2014). Even though many developing countries adopted IFRS fully or partially, it is clear that most of these nations are adopting the standards under pressure from international organisations like the World Bank, WTO, and IFM (Ibrahim,2014; Abeleje, 2019; Almansour, 2019). However, Libya still did not take this step; consequently, the delay in adopting IFRS is a gap investigated in this work.

3.3. Libya and IFRS Adoption

- IFRS adoption in the context of Libya has been recently explored in literature. For instance, Handley-Schachler, 2012; Lega, 2013; Elhouderi, 2014; Masoud, 2014; Zakari, 2014; Faraj and El-Firjani, 2014; Bayoud, 2015; Khaled; 2016 Binomran, 2021 investigated IFRS adoption in Libya. However, while these studies have set the scene, there are still numerous limitations that formed the basis for this study. Handley-Schachler (2012) assessed arguments surrounding the suitability of IFRS adoption and demonstrated difficulty in adopting IFRS in Libya. Similarly, Laga (2013) concentrated on the possible obstructions that will confront the procedure of executing IFRS in the case of Libya, even though the adoption of IFRS in Libya will have numerous advantages, including expanding the level of equivalence and giving a more dependable, precise, transparency and legitimate monetary accounting data. There are several limitations in adopting and implementing IFRSs into the accounting standards in Libya, including identifying language barriers as the main challenges, lack of technical expertise and accounting knowledge among the accounting professionals. In addition, implementing IFRSs in Libya will be fraught with difficulties due to several flaws in the country's accounting foundation. As a result, these practical roadblocks should be recognised and addressed to ensure a seamless implementation process and maximise the benefits of using IFRS (Laga, 2013). Although Handley-Schachler’s, 2012; Laga’s, 2013 research should be treated as critical in identifying issues relating to IFRS in Libya, these studies are based on an extended literature review without any primary data offered in support of the claims.Thoughtful insights about the adoption of IFRSs in Libyan businesses were provided by Elhouderi (2014). In his inquiry, he looked at the existing situation and looked at some of the best practices in financial disclosure requirements. Libyan financial reporting companies may be able to attract FDI thanks to their use of international financial reporting standards (IFRSs). Libyan foreign investments could be facilitated and bolstered as a result of this reform. This study relies on primary data, while Elhouderi's 2014 work relies on a review of previous studies. According to Elhouderi (2014), no extensive research has been conducted on the application of IFRS in Libya, even though such standards are ne desired.Elhouderi (2014) added, “Drawing from the planned carefully selected pool of Libyan companies in the research sample across various industries, but with some stress on oil and gas extraction, it is necessary to cover in future research”. Libya's mining industry would be the focus of the current project to address this void. IFRS implementation in Libya is expected to have positive effects on the stock market, according to a study by Masoud (2014). These benefits include improved financial reporting quality, reduced earnings management, increased comparability, and increased trustworthiness, precision, and transparency. “Due to the lack of high-quality published databases, this study uses secondary data, which were based on a literature review” (Masoud 2014, p135). However, the author recommended further studies on the context of Libya based on a triangulation method (questionnaire and interview) to obtain a comprehensive understanding of factors that have a positive or negative impact on adopting IFRS in Libya.Zakari (2014), on the other hand, studied Libyan companies' obstacles in implementing IFRS. According to the author, IFRS adoption in Libya was affected by the legitimacy of monetary, monetary, accounting training, and cultural frameworks in the country. Academics at Libyan universities were asked to complete a questionnaire about the impact of specific challenges on the implementation of IFRS in Libya. According to the survey, IFRS implementation by Libyan businesses was not free of challenges, such as a lack of accounting knowledge and training (Zakari, 2014). An assessment of the problems of IFRS in Libya, focusing on the impact of legitimate accounting rules, finances, and society on the implementation of IFRS, is presented in this paper. Even though primary research was conducted, the study's findings are based solely on one person's perspective' (academics).In contrast, the current research will consider additional perceptions from Accountants, Auditors, and Financial Managers. Along similar lines, Faraj and El-Firjani (2014) examined the factors Libyan-listed companies might face in adopting IFRS. The study showed that most companies follow the existing regulations and laws, such as Libyan commercial law and Libyan tax law. While these findings could be seen as vital, the observations cannot be generalised to other industries not operating in Libya’s stock market, such as oil and gas companies. Bayoud (2015) investigated the importance of IFRS adoption in Libya by using the perceptions of the Libyan accounts. This research confirmed that IFRS adoption would help stakeholders achieve the importance and benefits of IFRS adoption in Libya; however, there is a weakness in Libyan Accounts' knowledge of IFRS. Additionally, the study focused exclusively on the factors and obstacles associated with implementing IFRS, with no consideration given to the motivations for postponing implementation.Khaled (2016) pointed out the benefits of adopting IFRS in developing countries like Libya. In this work, questionnaires were distributed to various fields. The study suggested that the implementation of IFRS improves the quality of accounting information, increases disclosure effectiveness, and enables the comparison of financial reports (Khaled, 2016). However, the researcher distributed a total of 50 questionnaires, which arguably limits the scope of their findings. Also, several participants might be inadequately familiar with the IFRS as they are students. However, the researcher recommended that further study be carried out to reveal the benefits and challenges of adopting IFRS. Binomran (2021) survey explored the motivating factors affecting Libya’s adoption of IFRS using a questionnaire. Binomran highlighted that the milestone motivating factor of the adoption of IFRS in Libya is economic growth. Furthermore, the advantages of adopting IFRS constitute a powerful motivator for Libya to take that option. On the other hand, accounting education plays a smaller influence in pushing Libya to adopt IFRS. Despite the interesting outcome of the research, its scope is very limited as only 56 participants were used. Also, the researcher did not provide the reasons behind the findings because he used a single method. However, the study recommended using the exploration methods in future studies. Therefore, Binomran, (2021) recommendation has been adopted in the current research with an approach focused on the factors that motivate the adoption and the potential causes for the delay. Although adopting a uniform set of accounting standards such as IFRSs in developed countries has been given due attention, there is still a lack of research and investigation concerning the convergence of emerging economies with those standards developed and adopted in developed countries. The literature review indicates the emergence of similar patterns in developing countries: adopting and implementing IFRS could be highly challenging, expensive, and time-consuming. Whilst several studies have been conducted within the Libyan context, research has not examined the effect of IFRS adoption or the advantages of the accounting reform extensively (Masoud 2014; Elhouderi 2014; Faraj and El-Firjani 2014; Masoud 2016), especially in the oil and gas industry (Elhouderi 2014). Consequently, this study relies on a mixed mode to fill this gap by providing better information and understanding of the current challenges facing the implementation and adoption of IFRS into Libyan accounting standards. Furthermore, this research aims to evaluate whether there will be any opportunities arising from the implementation of IFRS in Libya. This work relies on the existing literature as a base but differs on the objectives as the aim is to find why Libya did not adopt IFRS yet (reasons for the delay).Since this part focused on adopting IFRS in developing countries, the researcher focused on the case study of Libya. The next part will focus on the benefits and opportunities developing countries like Libya could get from adopting IFRS; the challenges/obstacles to adopting IFRS are also discussed.

3.4. Benefits of IFRS Adoption in Developing Economies

- Many developing nations lack the economic and technological wherewithal to generate accounting and reporting standards. Furthermore, they may lack the regulatory authorities and strong professional bodies to produce and maintain indigenous accounting standards; hence, such countries can simply adopt IFRS (Fino, 2019). The potential benefits of this adoption will be discussed next.

3.4.1. Accounting Information

- The adoption of international accounting standards would offer a reasonably homogeneous, comparable, and credible information product to the decision-makers, both national and international (Nulla, 2014). Among the benefits of IFRS adoption include transparency, improved reporting quality, accounting, market efficiency, international comparability, and cross-national investment flow (Al-Mannai and Hindi, 2015; Li and Yang 2016; Nurunnabi, 2017). Financial reports generated according to IFRS are usually considered standardised and trustworthy than those prepared in compliance with domestic standards of accounting, such as being more informative to decision makers (Alsuhaibani, 2012). Compared to statements prepared according to local standards, empirical studies show that adopting the IFRS increases relevance and reduces the risk of earning management (Nulla, 2014). According to Tarca (2004), competitive market pressures encourage global enterprises to embrace IFRS, a standard accounting language, making it easier to compare financial reports and allowing corporations to easily benchmark their financial statements (Zakari, 2014; Nurunnabi, 2017A). Even countries that have previously adhered to their national accounting standards are now realising the importance of understanding the accounting of their international counterparts (Almansour, 2019). Even if adopting IFRS is important, it is not enough to simply implement the standards (Masoud, 2014A; Nurrunabi, 2017). The establishment of regulations for improving the computer arability of IFRS-based reporting is necessary since both mandatory and voluntary disclosure play a critical part in the comparability function of the accounting system.

3.4.2. Economic Growth

- Accounting helps form the investment climate by establishing processes and controls that inspire investor trust, which leads to healthy growth. IFRS are used by countries and enterprises to improve financial reporting, remove barriers to cross-border investing, increase market efficiency, and lower capital costs. According to (Albu and Albu, 2012), The Romanian motive for adopting IFRS is typically couched in broader terms and is primarily related to economic development. Adoption of IFRS lowers the capital cost, enables international capital mobilisation, promotes market development, improves value, and boosts market liquidity (Al-Mannai and Hindi, 2015; Nurunnabi, 2017; Almansour, 2019). The primary objectives were to accelerate the transition to a market economy and to attract FDI by establishing a credible and transparent accounting system that provides users, particularly managers, with accurate accounting information for decision-making. It has also been claimed that adopting IFRS is a legitimising move for emerging countries to promote themselves as an organized, and well-regulated modern place to do business (Hamawandy et al., 2021).Shifting from local GAAP to IFRS, various scholars (Odia and Ogiedu, 2013, Elhouderi, 2014, Nurunnabi, 2017) believed that IFRS adoption enhances the influx of FDI and allows businesses to expand globally. In addition, IFRS advocates frequently argue that harmonised accounting standards benefit market operators and economies as such improved financial reporting and transparency would improve investor demand for equities and minimise capital cost (Delcoure and Huff, 2015). The quality of financial data is a critical factor in capital markets’ development and effectiveness (Verrecchia, 2001).Abdulrahim (2015) argues that FDI improves the receiving country's growth and competitiveness, benefiting domestic and foreign businesses. This will benefit Libya to diversity the national income, which is currently 95% dependent on the oil and gas industry. According to Jermakowicz and Gornick-Tomaszewski (2006), countries with foreign investor-friendly financial markets are more positioned to adopt IFRS. Daske et al. (2008) noted that IFRS adoption improves stock market liquidity and Tobin's Q while lowering corporate capital costs. According to Lahmar and Ali (2017), adoption can boost the economy if strong regulatory authorities and regulations accompany it. Li (2010) on the influence of IFRS voluntary and mandatory adoption on equity cost showed that countries with strong legal enforcement gain from IFRS adoption as it lowers a company's cost of capital, as earlier reported by Zehri and Chouaibi (2013). In the view of Cameron (2014), corruption and tax evasion can be minimised only when there is accountability and tax transparency. In some African countries, the adoption of IFRS in a hostile environment can help achieve private and public accountability for revenue losses. Citizens will ask for transparency, credibility, and accountability of tax documents compatible with IFRS after its adoption, which may deter some taxpayers from engaging in tax fraud (Kurauone et al., 2021).The norms, culture, government servants, and general public expectations will all be less inclined to engage in corrupt acts if a country has regularly attained the good governance requirement of adopting IFRS, according to Rose and Peiffer (2019). According to Zeghal and Mhedhbi (2006), the implementation of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) does not have a significant impact on the economic progress of developing countries. Furthermore, the adoption of IFRS is not the only element that can help countries achieve faster economic growth, as trustworthy financial statements are needed to improve the investors' confidence. Other factors like legal aspects, cultural aspects and education play significant roles as they might be an obstacle to achieving economic growth; this challenge will be discussed next.

3.5. Challenges of IFRS Adoption in the Developing Economies

- Scholars have noted that IFRS adoption leads to the generation of high-quality accounting data, increased value-relevant information, improved firm comparability, and economic growth. However, some studies claim that IFRS adoption is ineffective in economically underdeveloped countries with subpar law-enforcement authorities as the resources are limited and there are fewer incentives for auditors and managers (Agostino et al, 2010, He Wong, and Young, 2012, Papadamou and Tzivinikos, 2013). Indeed, IFRS is appropriate for capital market-based organisations that are regulated, particularly in industrialised nations with strong legal enforcement, tight monitoring, and oversight. Many challenges to implementing IFRSs have been found, but they are not completely similar, and the degree of a challenge has not been experienced equally across countries (Wong, 2004; Ashraf and Ghani, 2005). Understanding these challenges will probably help countries (like Libya) adopt IFRS or intend to adopt IFRSs, to realise a better way of achieving international accounting practice (Wong, 2004). Some of the challenges of IFRS adoption from the perspective of developing nations are reviewed in the next section.

3.5.1. Accounting Education

- The literacy level is shown to correlate (Zehri and Chouaibi, 2013) with IFRS adoption decisions. While analysing the findings of 120 nations on IFRS adoption among listed businesses, Archambault and Archambault (2009) corroborated this notion on the impact of literacy level on IFRS adoption decisions. Other scholars (Zeghal and Mhedhbi, 2006, Zehri and Chouaibi, 2013) observed that countries with greater literacy levels showed more interest in IFRS adoption while researching the factors impacting IFRS adoption in developing nations. Furthermore, the choice to adopt the IFRS positively correlates with the literacy percentage of the countries surveyed. According to Nurunnabi (2017B) and Alsulami and Herath (2017), one of the most significant problems in implementing IFRS is a lack of professional judgment-making skills. This, according to both authors, is due to flaws in the educational system. The lack of a mature accounting profession capable of interpreting and applying the more critical components of IFRS could jeopardize the accounting profession's credibility. This can lead to blunders and errors, especially in the early stages of adoption (Fino, 2019). In precise terms, a lack of accounting education may hinder the proper application of the IFRS. Some of the accounting profession's issues include obsolete curricula, insufficient faculty members, and old teaching methods; all of these can impede the application of IFRS in various ways (Laga, 2013; Faraj and El-Firjani, 2014; Abeleje, 2019). Fino (2019) reported the adoption of the IFRS is an expensive procedure. Examples of such costs include translation costs, human training costs, software system modifications, the purchase of new accounting books, and the needed consultancy services. IFRS implementation in poor countries can be hindered by a lack of information and comprehension. Several authors have asked for more education on the topic because of this (Nurunnabi, 2015; Almotairy and Stainbank, 2014). According to Fino (2019), standards overload, firms' efforts toward complying with IFRS that are more complex than their business requirements, and the inability of local professionals to operationalise them are all challenges to IFRS adoption. However, these expenses may be considered a necessary investment in developing a country's financial system, account uniting and auditing education will aid in the smooth adoption of IFRS. Though teaching about the shift to IFRS can be difficult, the increasing number of tools accessible to accounting educators should help IFRS be taught successfully worldwide (Kurauone et al., 2021). In a similar vein, Al-Akra, Ali and Marashdeh, (2009) suggest that good accounting and auditing education helped in the smooth adoption of IFRS in Jordan. There has been some debate as to whether the incompetence of professional accounting groups, which the IASB relies on for guidance in the application of accounting standards, could be a further obstacle to a unified approach (Yapa, 2003, Joshi, Yapa, and Kraal, 2016).

3.5.2. Culture

- To construct an accounting system that fits their needs, developing countries should evaluate the importance of the cultural, social, economic, and political environment. They may, however, profit from using IASB-issued IFRS, while taking into account local environmental and cultural constraints is critical (Fino, 2019). The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) was founded to reduce the ensuing differences between national systems (Alsulami and Herath 2017; Alkhtani, 2012). According to Lasmin (2012), adopting IFRS in emerging nations is driven more by culture than by economic pressure since cultural values differ significantly among countries (Skotarczyk, 2011, Alkhtani, 2012, Alsulami and Herath, 2017). A big problem for developing countries in adopting IFRS is the language of the standards. The IASB issues standards in the English language. The translation of IFRS is a costly and time-consuming process. According to Nurunnabi (2017), language barriers are one of the most significant barriers to IFRS adoption in the country. For example, research on the transition to IFRS in Romania (Istrate, 2015) found inconsistencies in the translated Romanian version. Contrarily, Aljifri and Khasharmeh (2006) noted that financial information written in the English language might be considered a strong element in the decision of the United Arab Emirates to adopt IFRS. The advantage of utilising English as a reporting dialect in accounting standards comes as the firm opens itself to potential investors, raising its financial specialist base and diminishing its quality markdown. Zehri and Chouaibi (2013) claimed that developing countries with the highest literacy rate, high GDP growth rate, and effective legal systems are the most motivated countries to adopt IFRS, while on the other hand, cultural pressures, the political system, the existence of a capital market, and internationality does not affect the adoption of IFRS.

3.5.3. Legal

- Unified rules and a lack of regulatory methods, according to Mande (2014), are other potential issues to IFRS adoption. The country's political and legal system influences the quality of financial accounting and auditing as to many researchers (Salter and Doupnik, 1992, El Ghoul, et al., 2016). Furthermore, Almansour (2019) reported that the implementation must comply with existing rules and regulations, which include Sharia law in the case of Islamic countries. While English and French laws prevail in some African countries, Islamic culture has had a significant influence on the development of IFRS in other African territories. A hybrid legal structure in some states such as Nigeria and Mauritius makes it even more difficult to execute the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Due to religious rules that limit the amount of money a borrower can earn from a loan; Islamic lending does not allow for interest to be charged (this is the case for Libya which is governed under Islamic law). While it may seem like a good idea at first, this is in direct conflict with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) (Revenue).According to Tyrrall et al., (2007) have found, the adoption of IFRS provides more standards dealing with specific accounting issues, but they do not cover all of them. Thus, other national accounting standards or laws are needed to fill the gaps. Research also shows that the adoption of IFRS in many countries was modified to utilise the domestic GAAP (tax legislation) for taxation computations since variations among general financial information of tax purposes (tax laws) are significant. In Madagascar, for example, enterprises are allowed to create two financial reports (Chan, Lin and Mo, 2010; Chen and Gavious, 2017). Although IFRS adoption alone will not improve a country’s financial reporting quality, with strong legislative and judicial mechanisms in place, accurate and relevant financial reports may be created for financial reporting and taxation (Kurauone et al., 2021). IFRS adoption may come with many concerns and obstacles for developing nations; hence, addressing these issues one at a time would enable these countries to apply the standards (Fino, 2019) properly.

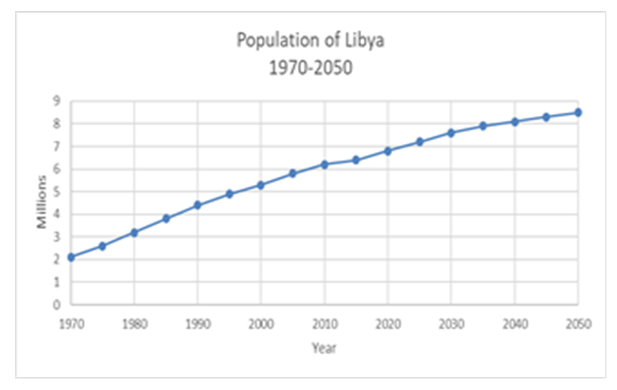

3.6. The Libyan Demographics

- Located in north-central Africa, Libya is the fourth biggest country in the continent by area.it is around 1.7-million-kilometre squares (World Bank, 2021). Whereas the west borders are shared with Algeria and Tunisia, the south and south-east with Niger as well as Chad, and the north and north-east with Sea and Egypt. The Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara Desert are two of the country’s most striking natural features. Nearly 95% of Libya’s terrain is desert or semi-desert, according to the World Bank (2021). As a result, the sea and the Sahara impact the climate. The country’s current population stands at around 6.9 million, giving a population density of 10 per square mile (World meters, 2021). According to the World Bank (2021), over the past 50 years, the population of Libya has grown at an average annual rate of 3. 5%, significantly larger than the average among African countries. However, based on the United Nations forecast, the population is expected to grow at a much lower rate of around 1% per annum for the next thirty years (UN, 2019). demonstrates the historic and forecast size of the population since 1970. Nevertheless, relative to the size of the country, the population density is one of the lowest in the region. Naturally, the major cities, such as Tripoli, Benghazi, Misratah and Tarhuna which have a much larger population density of between 30 and 40 persons per square mile of the total population, nearly 78% live in major cities and the remaining form the nomadic tribal population (World Factbook, 2020). In Libya, Men represent just over 51% of the population, with a life expectancy of 73 years. It is reasonable to claim that Islam has shaped nearly all cultural values and attitudes in Libya; since the people of Libya appear to adhere strictly to Islamic norms and values, both at work and at home (Jones, 2008). The idea of one Arabic nation as a substitute for the Western way of living appeals to many younger generations since Arabic culture is still so firmly ingrained in society (Obeidi, 2001).The country's formal language is Arabic, even though Italian and English are understood by a small percentage of the urban population (Alshbili, 2016). The colonisation of Libya by Italy meant that the Italian language became compulsory. However, since the defeat of the Italians in 1945 and the arrival of the Allied Forces to the country, the Italian language has demised across the country. On the other hand, due to the growth of businesses and links with international bodies, the English language has grown momentum in the country, particularly since the early 21st century (Aldrugi, 2013; Alshbili, 2016).Due to its extremely strategic geopolitical location, Libya has always faced invasions and colonisers due to that reason. Its colonisers include Ottomans, Italians, Carthaginians, Spaniards, Phoenicians, Greeks, Byzantines and Romans. In more recent history, Libya was ruled by the Ottomans from 1551 to 1911 and by the Italians from 1912 to 1943. Following the conclusion of World War II and the defeat of the Italians by the Allies in 1945, the country was managed by troops from the French and British. Libya was finally designated as an independent monarchy in late 1951 (Saad, 2015). Libyan society is primarily founded on traditional and conservative values with a strong tribal influence. The tribal influence is seen in the composition of the society and communities which consists of the small independent family unit to the clans (Jones, 2008). In this societal composition, loyalty to one’s region and tribes is paramount; therefore, this allegiance is expected in all spheres of society as favouritism towards one’s tribe. This is described as wasta in the Libyan colloquialism Abdulla (1999).

| Figure 1. Population of Libya 1970-2050 (UN, 2019) |

3.7. Political Economy of Libya: A Short Historical Overview

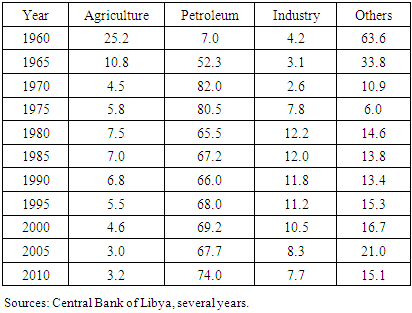

- Following the administration handover from the Franco-British to the Libyan government back in the early 1950s, the Kingdom of Libya was established. The early 1950s also saw the successful discovery and extraction of oil in the northern regions of Libya (Allan, McLachlan and Penrose, 1973). Following the joining of the OPEC in 1961, Libya became one of the main oil exporters, enabling the country to generate an annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate of around 20% for a decade (Wright, 1982). By the end of 1969, the oil revenues had reached just over $1.2 billion, turning Libya into the richest country in Africa (El-Fathaly and Palmer, 1980). Now around 47 companies and institutions operating in the Libyan oil and gas sector. For better or worse, Libya began its new life following the military coup led by Colonel Muammar Qaddafi in September 1969 which echoed the end of the monarchy. The military government proclaimed the Libyan Republic, and the county was controlled by the Revolutionary Command Council. in addition, people's Committees were founded in June 1973 after Colonel Qaddafi gave a long speech in which he claimed to have taken control of the national. As described by Qaddafi in his Green Book, where he profound what is called the "Third Universal Theory," the notion of Jamahiriya (Republic) sought to establish a socialist people's Libyan Arab state through an organisational framework that provided and allowed for direct democracy to be practised by its citizens (Allan, McLachlan and Penrose, 1973).Once the revolutionary government took power in 1969, it became clear how crucial oil production and exportation were to the country's economy as a whole. Although the regime appeared to be adamant about diversifying the economy away from oil dependency, the reality was that without oil revenues, the ambitious infrastructural investment and development plans would have been impossible to achieve (El-Fathaly, 1986). Following the nationalisation of many petroleums and other industrial activities back in the early 1970s, the demise of the private sector began to surface. Despite the emergence of several rather successful state-owned industrial and agricultural projects, the economy’s underlying growth began to slow down by the early 1980s (Kilani, 1998).In a nutshell, all businesses, small or large, were under the control of the government by the end of the 1970s. By the end of the 1980s, even the agricultural planning and food self-sufficiency projects - the jewel in the crown of the revolutionary government – had failed to deliver the success that the state had hoped. Billions of dollars worth of agricultural support to farming cooperatives and tribesmen settlers over 15 years had been unable to achieve the government’s objectives (Gwazie, 2004). The 1980s decade brought misery to Libya. Firstly, the oil prices, which have been primarily responsible for the economic growth and development of the country, began to decline sharply. Second, in the late 1980s, the US accused Libya of involvement in terrorist and anti-US actions, including the 1988 Lockerbie event. The US and UN imposed severe economic and political sanctions on Libya for nearly 15 years. In 2003, Colonel Qaddafi committed to compensating all Lockerbie victims' relatives in a Libyan-Western deal; Consequently, Libya officially opened up to the West in 2003 (Aldrugi, 2013). however, a wave of protests and military uprisings backed by the international world culminated in Qaddafi's collapse in October 2011. The autocratic administration of Qaddafi, which ruled Libya for just over 41 years, harmed the society and halted development and progress (Saad, 2015). The economy's overall performance before and after the 1969 revolution and up to the end of the Qaddafi era can be summarised in Table 1. Given that the main aims of the revolutionary government were to develop the industry/mining the agriculture and deviate gradually from the petroleum activity, the table demonstrates that in all aspects, the government of Qaddafi had failed to achieve these objectives. The pre-revolution share of agriculture is shown to have dropped once the oil exportation occurred in the mid-1960s. The post-revolutionary period up to 1985 saw slight improvements in shares of industry and agriculture from GDP. However, since 1990 the agriculture and industry sectors have been seen to be shrinking significantly whilst the petroleum sector has been steadily growing. These findings suggest that the regime failed to diversify away from petroleum-based activities and performed miserably in improving the industry and mechanised agriculture.

|

3.8. Accounting in Libya: Standards, Regulations and Practices

- The first attempt at introducing a set of commercial and financial laws began to emerge immediately after the independence of 1951. Before that, most practices in all aspects of commerce and accounting were based on some ad hoc and inconsistent standards in place by the foreign occupiers (Aldrugi, 2013). However, with the discovery of oil and the ever-growing need for domestic and foreign investment projects, the urge to develop internationally compliant accounting services became more evident. In meeting this requirement, the government had to issue temporary licences to firms in the oil and gas industry, enabling them to offer appropriate accounting services (Bait El-Mal, 1973).

3.8.1. Regulations and Standards

- Since independence, many regulatory measures have been introduced in Libya, primarily to aid the social and economic standards. In particular, since the discovery of oil and gas, a large number of such regulatory measures have been designed to safeguard and improve the standard of oil-related activity in Libya.

3.8.2. Libyan Petroleum Law (LPL)

- In 1955, the Libyan Government established the so-called Libyan Petroleum Law, containing 14 Articles. Whereas, petroleum is considered to be the property of the Libyan state, according to Article 1 of this law and all the exploration or yield must be conducted or authorised, or permitted by the state (Alshbili, 2016). The main pillar of LPL was deliberating the most effective way for the government to control the ownership and financial aspects of petroleum. Regarding the taxation on concessionary activity, Article 14 of LPL clearly states that operating companies are subject to income and other taxes under the Libyan tax structure but exempt from any other municipal or government taxes (Otman, 2006). Furthermore, the 2nd paragraph of the Article permits such companies to allow one-sixth of the value of export of crude oil as royalty and all other expenses (fees, rent, income tax) in their statements. Finally, this Article permits concessions to depreciate their assets at a fixed rate of 10% and amortisation of capital at a rate of 5% annually (Eldanfour, 2011). The LPL has also paid special attention to general and specific production-sharing agreements (EPSA) items. Furthermore, under this law, accounting requirements and rules are presented, clearly explaining the details regarding the presentation by firms of their profits and incomes after subtracting operating expenses and depreciation (Article 14: p. 18). Moreover, in bringing the accounting practices in line with the international principles in petroleum activity, the same Article requires firms to follow American and British standards (Saleh, 2001).

3.8.3. Nationalisation and EPSA