-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2019; 8(1): 1-22

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20190801.01

Chinese Supervisory Board and Audit Committee - The Comparison of Two Cases

Pao-Chen Lee

Kainan University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan

Correspondence to: Pao-Chen Lee, Kainan University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Chinese listed companies adopt first a Supervisory Board (SB) and then the independent directors in a Board of Directors (BoD). Specially, the Audit Committee (AC) of BoD and the SB are both in charged with monitoring functions in China. It may present that dual monitoring roles of SBs and ACs simultaneously operate in one organization in China. What are the processes and relationships between Chinese SBs and ACs? China expects that the establishment of ACs after SBs will improve the internal supervisory mechanism of Corporate Governance. Particular attention is paid to the challenges that both roles are facing in compositions, operational processes of coexistence and the likely linkages to their relationships. This paper compares two experimental cases with and without ACs in China by interviewing the SBs and ACs chairmen and members with scarce resources. A matrix of two cases studies’ results on the main features is summarized and the findings are given to improve effective supervisory functions in China. This research results propose that China may build up a suitable internal supervisory mechanism to Chinese unique model by integrating all of the supervisory institutions in one entity and raising the rank position to strengthen the functional processes and interactive relationships among the related parties. Chinese supervision in practical operations needs greater consideration of the organizational and institutional relationships and overcoming operational challenges of functional processes call for further researches.

Keywords: Supervisory Board, Audit Committee, Corporate Governance

Cite this paper: Pao-Chen Lee, Chinese Supervisory Board and Audit Committee - The Comparison of Two Cases, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 8 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-22. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20190801.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949 with the planned economy. Since 1978, China initiated the reform and opening-up policy, to the end of 2016, there are more than 70% of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have been renovated to the competitive commercial category as private enterprises, only less than 30% SOEs remained and categorized as public infrastructures (Cheng, 2012; GLGA, 2017). The goal of this new measure is to transfer control and management of SOEs to corporation systems in the end of 2017; and to establish a majority of external directors in the board of directors (BoD) in 2020 (OSC, 2017). The other reforms that accompany the changes of categorization and mixed ownership are strengthening the supervisory mechanism such like supervisory board (SB), BoD, implementing market-based manager compensation, and increasing accountability toward state owned assets to reduce corruption. There is nothing about altering internal measures for SOEs in order to ensure that these firms become more competitive or efficient (Hsu, 2017). Due to non-state owned interests in the joint ventures, demand emerged for the verification of capital contributions and audits of annual financial statements and income tax returns by registered non-government-employed Chinese certified public accountants (Xiao et al., 2000). There is inevitably to further strengthen the supervisory mechanism accompanying with the ownership conversion for the contradiction between the ownership and the management grounded on the agency theory. At the progress of supervision, the supervisory concept and independent monitoring knowledge in China was virtually non-existent under the planned economy before the 1980s, when the State both owned and ran enterprises. Since 1998, the SOE’s inspection commissioner’s system progressed to outsourcing board of supervisor’s system of the large SOEs, which were set up with the original intention for the transitional arrangements and with the subtraction members of the supervisors, has now been normalized and evolved into the enterprise’s supervisory board (SB) system (Zong, 2008). The progress of full-scale economic reforms, with the separation of ownership and management of enterprises, led to agency problems in business firms. Independent monitoring is thus called for, in order to alleviate these problems.The Chinese Corporate law adopted in December 1993 became the first piece of Chinese legislation specifying that every listed company establish a SB to supervise the company’s financial activities and the conduct of its directors. In 2002, China announced the regulation of the Code of CG for Listed Companies (CSRC and SETC 2002: Section 52), encouraging listed companies to set up an Audit Committee voluntarily, although its installation is not mandatory. In practice, the willingness to install the AC has increased from 1% (12) in 2000 to 99.86% (2106) in 2010 among listed companies (Lee, 2015, page 2, Table 1). In China, under the equivalent regulation, the establishment of an AC is voluntary rather than mandatory. In practice, the willingness to install the AC has increased and given that almost all Chinese companies have introduced ACs into their governance structures since 2010, it is indeed a peculiar system of implementing a singular mechanism of the AC on top of the dual supervisory mechanism of the SB. Given that the SB in the Chinese system has similar duties to that of the AC in the Anglo-American system, it is unclear how these two bodies will operate together and interacts with each other and whether this will result in the duplication of supervision. The issue in this article may be summarized as follows: What are the processes and relationships between Chinese SBs and ACs? Particular attention is paid to the challenges that both roles are facing in compositions, operational processes of coexistence and the likely linkages to their relationships.

|

2. Literature and Regulation

- LiteratureCorporate failures (Christensen, Kent, Routledge & Stewart, 2015) and increasing business risks (KPMG, 2015) impel the establishment of supervisory mechanism such as Audit Committees (AC) were introduced to form in the board in 1940 (US SEC), as a mechanism to solve the agency problem arising from the separation of the firm’s agents of managements from its owners of capitals (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Rossouw, Van der Walt & Malan, 2002). The AC is expected to provide assurance on compliance aspects; improve accountability (Brennan & Solomon, 2008) in terms of financial, control, risk, and audit matters (Marx, 2009) and to serve as an advisor (Magrane & Malthus, 2010). The effect of an AC may not proved only by its mere existence (Lisic, Neal, Zhang & Zhang, 2016; Sommer, 1991). The expectation to ACs was remarked as ‘the financial watchdog of the shareholders specifically, and all stakeholders at large’ (Marx, 2009:31). Many ACs could be ‘toothless tigers’ (Lublin & Macdonald, 1998) and only form for window-dressing purposes. More Expectations to the ACs have evolved as a corporate governance structure (Lin, Xiao & Tang, 2008; Narayanaswamy, Raghunandan & Rama, 2015).Block and Gerstner (2016, p50) find that the American board has begun to reflect German two-tier model in function if not in form and they remark “The heightened monitoring standards for boards and the rising importance of committees has made the one-tier board in America more akin to a multi-tiered board.” Gorton and Schmid (2004) document that under the German Corporate Governance (CG) system of co-determination, employees are legally allocated control rights over corporate assets through seats on the SB—that is, the board of non-executive directors. In line with the principles of the agency theory, these initiatives mainly aim to improve a board’s monitoring potential by increasing its independence from management (Daily et al., 2003; Finegold et al., 2007; Ramli et al., 2010). Bezemer, Maasen, and Van Halder (2012) suggest that a separate board with the power to influence management through consent, advice and incentives is an effective, pre-emptive form of monitoring. Firth, Fung, and Rui (2007) find that the types of the dominant shareholder, the size of the SB, and the percentage of independent directors have an impact on the frequency of modified audit opinions. Chien, Mayer, and Sennetti (2010) find that the presence of a committee and the committee’s specific qualities of independence, financial expertise, and increased activity positively correlate with reduced frequencies of internal control problems. In addition, Iyer, Bamber, and Griffin (2013) find that professional accounting certification and AC experience are valued positively by the BoD when designating an AC member as a financial expert. Typical measures to improve a board of directors’ independence include increasing the number of outside non-executive directors, separating the roles of the CEO and the chair, limiting the number of board interlocks and establishing oversight board committees. Qin (2007) examines the relationship between corporate performance and the characteristics of the SB. He suggests that the SB functions effectively in China and that improving SB functions could result in better corporate performance. Ding, Wu, Li, and Jia (2010) report that China’s CG system implements both American and German style mechanisms, but the SB, a typical feature of German style governance, is generally considered dysfunctional. One specific proposal for improving the SB system advanced in Wei and Jiang (2010) is to create public supervisors and creditor supervisors. As a result, board systems appear to evolve and converge around the globe (Bezemer et al., 2007; Chhaochharia and Grinstein, 2007; Valenti, 2008). Block and Gerstner (2016) stressed that another important monitoring task is the supervision of executive actions, where effectiveness depends on (1) independence from management, (2) information access and (3) overcoming operational challenges. For future research, Stuart and Zaman (2014) suggest: (1) greater consideration of the organizational and institutional contexts; (2) explicit theorization of the processes associated with operation; (3) complementing extant research methods with field studies; and (4) investigation of unintended as well as expected consequences of supervisions.In summary, China has entered a period of unprecedented transformation, within which business operations have become more complex. China’s internal supervisory structure involves a unique interaction between two mechanisms of ACs and SBs, and the function’s effectiveness, operations and co-ordination between these two governance elements represent important subjects for research. The supervisory characteristics of the composition including independence and expertise, and the operation including size and diligence are a prerequisite for the effective exercise of monitoring functions. It is a period of rapid innovation as well as that of trial and error in the evolution of businesses and business processes. The relevant studies all suggest that China must enhance supervisory mechanisms in its listed companies and the development of the capital market by refining the basic principles of law as well as by learning from the best reform practices of domestic and overseas CG.RegulationAC. The term ‘‘AC’’ means—a committee (or equivalent body) established by and among the BoD of an issuer for the purpose of overseeing the accounting and financial reporting processes of the issuer and audits of the financial statements of the issuer. (U.S. Securities Exchange Act of 1934 #3 (a)(58); SOX Section 404, 2002)These definitions state that the AC is a sub-committee of the BoD and confine the definition mainly to the composition and the key responsibilities of ACs. The composition of the AC particularly regard to the participation of independent directors with professional abilities to perform the key responsibilities of financial reporting, audit, and internal control. In a nutshell, the AC tends to emphasize the two attributes of its composition, namely independence and financial expertise, as well as its responsibility over operations. It is the duty of the Audit Committee to ascertain that the Company maintains adequate procedures and control systems to manage the financial, operational and risks to which the company are exposed, to prevent fraud and to oversee the integrity of the Company's financial reporting (FRC-UK, 2016). According to Section 52 of the Code of CG for Listed Companies in China, the BoD of a listed company may establish an AC. China’s “Rules for Listed Companies Governance” set out five main duties of CG for the AC: 1. Provide suggestions for engaging or changing the external audit firm (CPA); 2. Supervising the Internal Audit system and its implementation; 3. Be responsible for the internal and external auditing communication; 4. Verify and reveal the financial information of the company; 5. Check the internal control system.SB. According to the German regulations on CG, the SB (Aufsichtsrat) oversees and advises the BoD (Executive Board, Vorstand), and also has control over fundamental and important decisions. According to Paragraph 1 of Article 111 of the German Company Act (Aktiengesetz; AktG), the SB has the right and responsibility to oversee (u berwachen) the operations of the company (Chen, 2007, p. 154). The supervisory board reviews the management by inspecting the books1, reviewing the annual report2, issuing and overseeing the work of an external auditor3, analyzing the information provided by the management board4 and reporting to the general meeting5. In addition, the supervisory board also has standing for court actions against the management6. The characteristic of the existing German system of CG indicates that the SB plays the role of overseeing the operations and finance of the company. In addition to the appointment and removal of directors, the most important right and responsibility of the SB is to oversee the operations of the directors (Yang, 2004, p. 102). In the Chinese system of CG, there are two institutions participating in the Shareholders Assembly Meeting: the BoD which is responsible for making important day-to-day managerial decisions, the removal of managers, and the execution of day-to-day operations, whereas the SB is responsible for the supervision of the company’s finance, the violation of laws, regulations, or company constitution by the directors and managers in their execution of their duties to the company (Yang, 2004). According to Article 126 in China’s Corporate Law, the SB in a Chinese company is the internal supervisory unit responsible for supervising the directors and managers’ behaviour. Corporate Law also stipulates the system of the SB and guides it on behalf of the shareholders to supervise the organization of internal power, exercised by the BoD and the layers of management of the company. In both the German and the Chinese systems, it is the right and responsibility of the SB to oversee the conduct of the BoD. In the German system, the SB has a rank position above the BoD, whereas in the Chinese system, the SB has the equal rank position as the BoD. This structural difference might have some impact on the supervisory effectiveness, the powers, and roles of the SB in both systems. The duties of SB as stipulated in Corporate Law include: 1. Reviewing the financial affairs of the company; 2. Monitoring the performance of directors and senior officers; removal of directors or senior officers in the case of violation of laws, administrative regulations or articles of association; 3. Requiring rectification from directors or senior officers if they cause harm to company interests; 4. Proposing interim shareholder meetings; convening shareholder meetings when the board of directors does not do so as required by law; 5. Submitting proposals at the shareholders meeting; 6. Filing suit against directors or senior officers if they harm the company while performing their duties in violation of laws, administrative regulations or the articles of association; 7. Exercising other authorities set out in the articles of association.First, the Chinese Security Regulatory Commission (CSRC) mandated that both the SBs and the ACs were responsible for financial supervision, and both have the same financial supervisory function of overseeing the authenticity and reasonableness of the disclosure of the company’s accounting information. Second, both are responsible for safeguarding against questionable conduct of the Directors, and related transactions of senior managers. The duties of the AC and the SB as stipulated in Corporate Law and the Code of CG for Listed Companies in China are essentially similar; both try to monitor within the company’s functions on the same issue, identified as supervising financial reporting, auditing, internal control and compliance. However, organizationally they are not affiliated to each other, as the AC is under the jurisdiction of the BoD, while the SB is parallel to the BoD. This can cause confusion in their respective responsibilities if there is lack of clarification or co-ordination, and it may appear that many institutions are supervising but no unit actually performing that function. Clarification the defects of performing monitoring functions in China or co-ordination includes defining the duties, functions and position between SBs and ACs in the organization, but such clarification measures are still outstanding. Therefore, this paper endeavors to investigate on compositions, operational processes and relationships with the coexistence of two monitoring institutions.

3. Research Methodology

- DesignThis article aims to answer the research question by interviewing two experimental case studies in China and referring to the work of Block and Gerstner, Gendron, Be´dard, Turley and Zaman, Spira, and others. As these researchers performed only limited research on internal processes, they have called for more research to be carried out. Semi-structured interviews provided participants with an opportunity to reveal any important matters relating to the studied phenomena, which were not adequately covered by the guiding questions (Myers, 2011). Thus, the semi-structured interviews with the SB and AC chairman and members will help identify the compositions, operation processes and their relationships of both supervisory institutions rooted in their practical experiences, in response to calls by the relevant researchers to unravel the black box of the monitoring system, as this cannot be achieved through quantitative methods. A qualitative design is therefore properly used in this study (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). Generally, the qualitative method will compare two cases to discover the compositions, processes and relationships from both sides of SBs and ACs inside viewpoints on understanding SB/AC motive force and revealing the contexts of supervisory functions in both sampled companies. As well as the qualitative method will analyze the responses from three interviewees of each case to identify operational processes and the interactions of their relationships on the understanding of the SB and AC concrete practices of implementation. The researchers who interpreted the participants’ multiple subjective views, acted as constructivists to develop themes (Creswell, 2007). The researchers’ paradigm accordingly influenced the qualitative research approach chosen to address the research objectives (Creswell, 2007; Fouché & Schurink, 2011).Sample TargetTwo case studies were conducted, corporation A with SB alone, and corporation B with SB plus AC, three members of each case were interviewed. Empirical data was primarily collected through semi-structured interviews, which were validated (Creswell, 2007; Yin, 2013) by reviewing company documents (e.g. annual financial statements).Case A (SB alone):The sampled company of a chemical and logistics industrial group listed in the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) with three interviewees, one SB chairman and two SB members were interviewed. They are all employees of the affiliate company, in charge of the internal audit department, and the administration department. The Chairman has a lawyer’s license; one supervisor is an experienced auditor and has been a member of the SB for five years. Another member has been a member of the SB for fifteen years, a representative of state owned stocks previously and employee owned stocks now. All three have no financial expertise.Case B (SB+AC):The sampled company of engineering machinery Co., Ltd. listed in the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) with three interviewees, one General Secretary of BoD; one AC member and one SB Chairman were interviewed. There are four SB members and three AC members in case B. Three supervisors are all employees, and the Chairman is also in charge of the legal department. The second supervisor has the certificate of public accountant in charge of the accounting department. The third supervisor is employed as a mechanic. The fourth supervisor was not interviewed, but is independent and is CPA certified. Overall, two out of four supervisors have financial expertise. Among the interviewed members of the AC, one is an employee and shareholder in charge of the finance department; one is an independent director in the economics profession. Another independent director is a professor without a financial background. Overall, one of the AC’s three members has financial expertise.The interviews were conducted after the introduction of the General Secretary of the BoD, as he is in charge and the coordinator of the BoD and the SB, including ACs and its related parties. Three interviewees of each case were questioned about the process of typical supervisory functions and the extent to which the company’s SB and AC fulfilled its mandate in practice in China, to make data collection more systematic for each interviewee, it was intended to keep the interview fairly conversational and situational. The data were then analyzed and consolidated to generate conclusions.Conversation AnalysisThe research participants were selected according to their ability to provide information about the phenomena being studied (Saldaña, 2011). All interviews were video recorded and transcribed. Semi-structure interviews were used to allow the interviewee to express their points of views for mutual understanding related to the AC’s relationships (Rubin and Rubin, 1995). The interview transcripts were analyzed through qualitative procedures (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Afterwards, for each corporation, a conceptual matrix was prepared, summarizing the main themes discussed by the interviewees, before re-examining the interview material to gain a better understanding of the answers surrounding implementation in motive force, difficulties, process and relationships (Gendron and Bedard, 2006) and future expectations in China. To further ensure the validity of the interviews, the analysis ensured the interviewees’ answers within the same corporation converged (Gendron et al., 2004). The two case studies’ conceptual matrices provide a database in preparing an outline on the findings of the paper.TechniqueData analysis of interview transcripts was processed in four steps as follows:1. To develop a coding scheme;2. To modify the scheme when new themes emerged from the data;3. To develop a conceptual matrix to summarize the main themes; and4. To examine the relationships that might exist among these themes.After the initial coding, this process was repeated after importation into the Atlas.ti computer assisted qualitative analysis software. Similar descriptive codes were grouped together and assigned to specific descriptive categories (Babbie, 2010; Saldaña, 2011). The interrelationships among these categories were then explored (Saldaña, 2011) with common themes identified to contextualize the activities. “The analysis has selected feelings, problems, and so on according to some explicit decision rules and has clustered discrete but similar items” (Miles and Huberman, 1994: 178). This study clarified similar variables along with two investigated case studies in order to summarize the findings. The trustworthiness of the findings was increased by comparing the coding report to an experienced independent co‐coder’s report (Lincoln & Guba, 1999). However, this research also aims to construct theoretical generalizations rather than statistical generalization (Ryan et al. 2002: 149) pertaining to SBs and ACs operations and co-ordination of the dynamic relationship with each other and other parties. Actually, “Case studies can provide ways of thinking about problems” (Scapens, 1990: 279). Hence, this study uses case study and interview in order to examine the difficulties involved in processes and relationships to evaluate the benefits of both applications and point out findings for improving the effectiveness of supervisory functions.

4. Empirical Studies

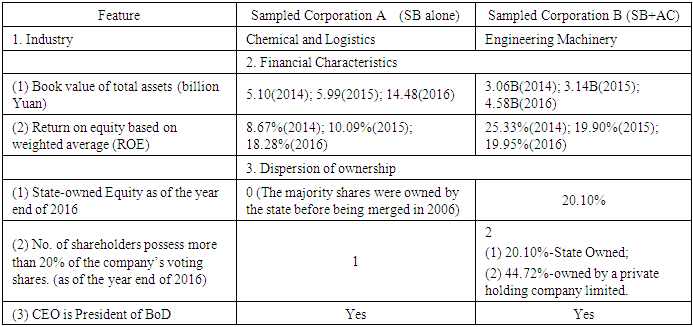

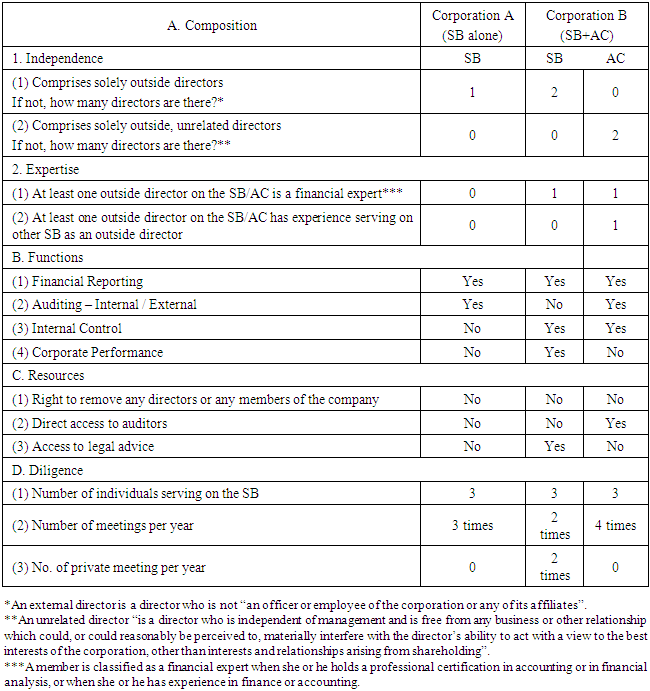

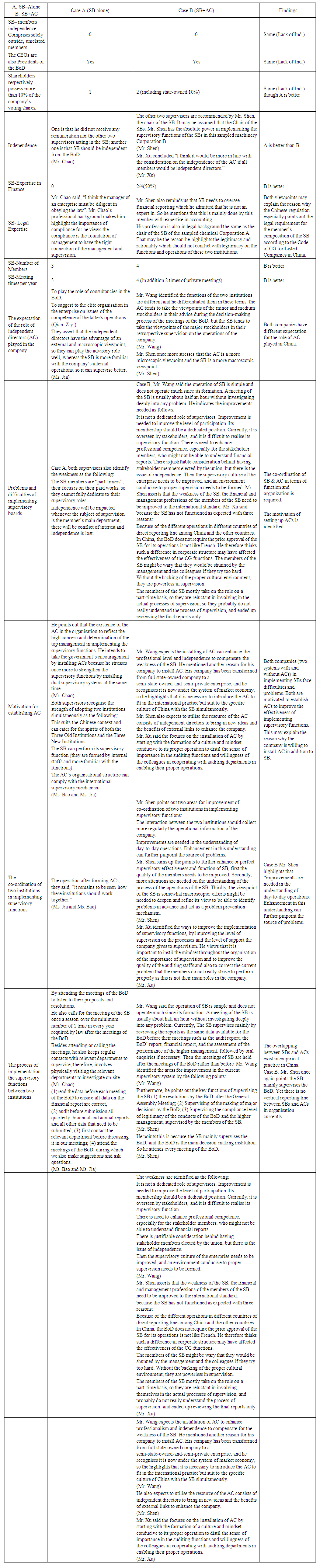

- (I) Backgrounds of two casesTable 1: Case A / B is growing bears book value of total assets 14.48 / 4.58 billion Yuan (2016) according to their return on equity over the past three years from 8.67% to 18.28% / 25.33% to 19.95% (2014-2016). State-owned equity percentage occupies 0% / 20.10% though Case A majority shares were owned by the state before being merged in 2006 and Case B majority shares were owned by the state before being merged in 2000 in the process of transitioning from being state owned companies to the employee and the public. Case A/B bears 1 / 2 shareholder possesses more than 10% of the company’s voting shares. Case B, one is 44.72% owned by a private holding company limited; another is state owned 20.10%. The independence of both cases is questionable, for both the CEO is also President of the BoD.(II) Features of two casesThe Table 2 is based on the data provided by the sampled companies and financial statements.

|

| Table 3. Matrix of the Comparison of Case A (system A – SB alone) and Case B (System B – SBs plus ACs) in China (Source: Author) |

5. Conclusions

- This paper compared two systems of Chinese SBs' operations with and without ACs presents Chinese dual boards have begun to learn from the American board in AC’s functional processes and also need to learn from German system in SB’s institutional position mainly aim to improve monitoring potential by increasing its independence from management in organizational relationships. In general, SBs do not participate in the decision making of the company’s management, nonetheless their governance function can be enhanced by focusing on examining the company’s finances, supervising the regulated activities of directors, and last but not least, overseeing the reporting of information and the legal responsibilities of the directors and managers. According to two case studies’ interviews, both acknowledge the operational challenges in implementing the SBs and both cases expect the establishment of ACs to improve effective supervisory functions in China. Yet there may be further problems after adding in AC. The issue calls for being further explored as the follows: The co-ordination of two institutions in implementing supervisory functions. The SBs and the ACs are supervisory institutions under different CG models. Yet there is no vertical reporting line or integration between SBs and ACs presently or standard procedures of implementing supervisory functions between two institutions. It is suspected that incorporating both into one model will result in functional overlaps and gaps. Furthermore, how to solve the overlapping and missing items between SBs and ACs existed in empirical practice in China? How to interact with each other and with the other related parties such like Internal Audit and CPA firms? If the proposal for modification to improve co-ordination among the institutions of the internal supervisory mechanism and merge them into one entity is carried out, it will eliminate the problems of overlapping or missing functions. At the same time, it will not impact upon the checks and balances between the BoD and the SB in improving the deficiencies existing in the internal supervisory mechanism of both the German and the Anglo-American CG models. To co-ordinate the organization of the SB and the AC into one entity will make the co-ordination of their functions much easier. The recommended pattern is an innovative breakthrough, which will remove the limitation and the constraint inherent in the supervisory mechanism of CG in China as well as build up a suitable internal supervisory mechanism to Chinese unique model. Two cases studies and the interviews reveal Chinese supervision in practical operations. Despite its Chinese orientation, the study findings are globally relevant, since enterprises with ACs only around the world are acknowledged still with the loopholes and scandals as the well-known cases of Enron and WorldCom that lead to explore the breakthrough ways properly with consideration of their institutional and organizational context.

Appendices Interview Transcripts

- Case A (SB alone):The general secretary of the BoD is co-ordinated the individual interview meetings with members of the SB. Mr. Qian introduced his company to the author before progressing into the individual interview, as transcribed below.A.1 Interview with Secretary of the BoD of the sampled Co., Ltd., Hangzhou. [Video recording in possession of author]A.1.1. What are the roles of the independent directors in your company?The independent directors play the role of consultancies in the BoD. They have the responsibility of professional supervision. First, they have the right to suggest to the elite organization in the enterprise on issues of the competence of the latter's operations. Secondly, they can indicate the level of operations of the elite organization in comparison with its rivals. Since independent directors are external to the organization, it is possible to expect them to play the role of supervising the supervisors internal to the organization.The conversation with Mr. Qian provides a background on this company’s cultural integration from being state- owned to being privately owned, and from the spirit of a party run enterprise to that of a private enterprise. His personal viewpoints on the role of the independent directors naturally lead to curiosity regarding the implementation of supervisory functions in this case. The first interviewee, the Chair of the SB is then introduced as follows:A.2. Interview with Mr. Zhao, Chair of the SB of the Sampled Co., Ltd., Hangzhou. [Video recording in possession of author]A.2.1. What are your opinions on the supervisory system since its introduction in 1993?It is very important to have an independent supervisory system. It is especially so for our company. Since its flotation, the expectation from our investors has grown steadily as we improve the execution of the supervisory system in our company year on year. There is first the SB and then the independent directors in the Chinese system. Since I first served on the SB, I have been neither a stockholder nor a beneficiary of the company. I do not receive supervisory fees on top of my salary for my post company. The other members of the SB are employees, and they do not receive any payment in addition to their respective salary except an annual traffic expense of RMB 5,000. It is stressed that the BoD and the SB should operate independently. It is the responsibility of the SB to independently supervise the BoD, so it should not be led by the latter. Though my speciality is in law (rather than finance or accounting), there are several finance and accounting professionals in the auditing department of the company, and all public financial reports and information have all been audited by the external auditor before their submission. The external audits are provided by the Tianjian Accounting Ltd.A.2.2. How does the SB operate?The SB holds the internal supervisory meeting before the meeting of BoD. I personally review the managerial report of the BoD before their meeting. I attend about 6 to 8 meetings every year. These include the meetings of both the BoD and the SB. The main purpose of attending the meetings of the BoD is to listen to their proposals and resolutions. I call for the meeting of the SB once a season. The minimum number of such meetings every year required by law is two, and these are usually held after the meetings of the BoD in other companies. I also keep regular contacts with relevant departments because problems cannot all be identified by merely reviewing financial data, as demonstrated by the Enron scandal. To supervise, therefore, involves physically visiting relevant department such as the financial and auditing departments to investigate on site. The auditing department is utilised heavily. The auditing of the financial reports is solely handled by the external auditor, whereas the main responsibility of the auditing department is to alert the SB of potential problems and perform necessary investigation. This is because the supervisory function of the SB should act as the radar system in the company that can detect problem in advance to prevent its occurrence and damages to the company. It is important to allow flexibility in the power of management within the confine of the law, but the SB should, like a radar system, sound the alarm and request control whenever the boundary is crossed. In short, the SB should perform its function of prevention.A.2.3. What are the foci of the SB’s supervision over the financial reports, auditing reports and internal control?These are truthfulness, the analysis of the rationality of data, and the proper operations of the SB. The reports of the SB are signed by the Chair of the SB before its submission.A.2.4. What is your view on acting as a member of the SB?It is a matter of organizational culture. The culture of our company stress “sincerity, innovation and development,” so we are not afraid to identify problems. As our MD says, “it is our wisdom to identify problems, it is our attitude to face problems, it is our virtue to acknowledge problems, and it is our responsibility to solve problems.” By the end of this month, he is to hold a meeting asking every department to identify problems. This enterprise cannot develop if problems are not identified. Even though the company has been around for a long time and the SB has been installed for quite a while, the purpose that the MD appoints me to serve on the SB is to identify problems to prevent these causing damages to the company.A.2.5. Why do you want to install the AC?First, we value the work of auditing very highly. Secondly, we must have it, (as) if it functions properly; it shows that the top management is determined to execute (proper auditing). It can hardly function if the top management does not value it.A.2.6. Once the AC is installed, will there be organizational or functional overlap with the SB?There will not be any organizational overlap, as the AC is under the BoD whereas the SB is a peer of the BoD. The installation of the AC will only let the auditing function be valued more and make the operations more transparent, thus making it easier to identify problems, by utilizing the supervision of the public departments. Furthermore, as our enterprise grows and expands, there has to be an auditing department in each company and it is definitely necessary to have an AC in the umbrella company. As to the issue of functional overlap, the focus of the AC is on internal audit, whereas that of the SB is on the BoD.A.2.7. Do you think there is any space for improvement in the current supervisory mechanism?This is the focus of the government. There are cases of falsification all over the world. False reporting should be severely punished.A.3. Interview with Mr. Bao, and Ms. Jia, two members of the SB of the Sampled Co., Ltd., Hangzhou. [Video recording in possession of author]A.3.1. As your company is forming the AC, there will soon be both the SB and the AC in your company. Do you think these two institutions will have similar or identical characteristics?Bao: (The adoption of these two institutions is) adapted to the Chinese context, the functions and powers of these two institutions are different, and these will be clearly stated in the constitution of the company.A.3.2. Do you think it is necessary to form the AC?Jia: Judging from the specifications in the regulations, I feel there will be overlaps between the responsibilities and powers of the AC and the SB, but I personally think that the members that form these institutions will be different. The members of the SB are internal representatives of employees, so they know about the situation of internal management better. The members of the AC are external independent directors, who have more involvement with external roles, and consequently have a better, more macroscopic view of the external environment, but they may not be as familiar with internal operations as the SB members. Thus, the existence of the AC can enhance the SB’s understanding of the external economic and supervisory environment. Therefore, I think the two institutions can be complementary to each other and work together to improve the supervisory mechanism.A.3.3. In your opinion, once the AC is formed, how should the functions of the two institutions be distributed in practice?Due to the different types of members forming the two institutions, the SB that is formed by internal staff should be responsible for the supervision of internal matters, whereas the AC that is formed by external independent directors could engage in the collection of external development related data for the development of the supervisory function. External independent directors engage in investigation only under special circumstances. Thus one works from without, one from within, with proper communication between them; the two institutions can complement each other in the supervision of the company.A.3.4. The AC and the SB are at different positions in the organizational structure. How should these two institutions interact with each other?The BoD, leading the whole management team, is responsible of the practical running of the business. The AC is under the BoD, and is responsible of assisting the BoD to confirm with laws and regulations. It can supervise before a decision/resolution is made by the BoD. It can also supervise during the operations, such as overseeing if the management is operating according to the decision/resolution of the BoD, or if the reporting confirm to the requirements of the laws and regulations. The SB is of equal rank with the BoD. It remains to be seen how these two institutions should interact with each other in organisation.A.3.5. What is the SB’s role in regards to supervising the financial report, the audit report and internal control?There are many regulations about the financial report, the audit report and internal control of a listed company. It is essential to comply with the regulations. We have to keep up with the pace of innovation in order to progress.A.3.6. How does the SB of your company work?Jia: According to the responsibilities specified in the Company Act and the company’s constitution, we must read the data before each meeting of the BoD to ensure all data on the financial report are correct. We also audit before submission all quarterly, biannual and annual reports and all other data that need to be submitted. In case of any problem, we will first contact the relevant department before discussing it in our meetings. We meet at least three or four times. Each meeting lasts at least three hours. We check if the data reflects the actual situation of the company, make resolutions, and then submit the findings. In addition to holding SB meetings, we also attend the meetings of the BoD, during which we also make suggestions and ask questions.A.3.7. What do you think are the strengths and weaknesses of the current SB of your company?Bao: According to the Corporate Law, both the BoD and the SB are elected by the General Assembly Meeting. There are two stockholders’ representatives in the SB, who are elected by the stockholders, who hold votes according to their shares. There are stakeholders’ representatives in the SB, who are elected by the stakeholders. Additionally, according to our company’s constitution, there must be stakeholders on the SB, and at least one third of the members of the SB should be stakeholders’ representatives. I myself am a representative of both the stakeholders and the union, and I represent the stakeholders (on the SB). The purpose of the SB is to supervise the BoD. If the BoD supervises itself, there will be no independence (in supervision). There have been the Three Old Institutions and the Three New Institutions in the Chinese system. The Three New Institutions are the General Assembly Meeting, the BoD and the SB, whereas the Three Old Institutions in state-owned enterprises are Party Officers’ Committee, the Union and the Stakeholders’ Representatives’ Committee. Now there is the problem of bridging the Three Old Institutions and the Three New Institutions. The elected representatives are responsible to the stockholders and the stakeholders; they are supposed to take their responsibilities seriously even though there is no additional financial reward for taking up these responsibilities. Hence, the strength is that the SB members are elected. Whoever does not perform well will not be elected again next time. First, this suits the Chinese context and can cater for the spirits of both the Three Old Institutions and the Three New Institutions. Secondly, as it is mandatory to have the SB, it can perform its supervisory function. Furthermore, now that the company is to form the AC, so its organisational structure can comply with the international supervisory mechanism. The weakness is that all the SB members are “part-timers”. Their focus is on their paid works, so they cannot fully dedicate to their supervisory roles. After all, there are limits to one’s energy. If the supervisory role is a full-time paid position, the performance of the supervisory function can be expected to be better. Moreover, whenever the subject of supervision is the member’s main department, there will be conflict of interest and independence is lost. For instance, Ms. Jia is responsible of internal audit department, so she loses his supervisory independence whenever the SB needs to supervise the internal audit department.A.3.8. How do you think the supervisory function will be improved?Once the AC is formed with independent directors in addition to the SB, the independent directors have the advantage of having an external and macroscopic viewpoint, so they can play the advisory role well, whereas the SB is more familiar with the company’s internal operations, so it can supervise better. The co-operation between them will enhance the supervisory function.A.3.9. How do you think can the supervisory function be executed in the current Chinese context?It is about the Three Old Institutions and the Three New Institutions. In the days of the state owned enterprises, the supervisory function was not realised in practice. After enterprise renovation, state owned enterprises are restructured to become private enterprises or even listed companies. The Three new Institutions are formed in addition to the Three Old Institutions. The BoD focuses on the development of the enterprise. The SB focuses the supervisory function. The existence of the SB itself makes a difference. Its existence represents the emphasis on the supervisory function. The SB has to perform its expected supervisory function in supervising the BoD and the higher management in any case. Furthermore, if the position of the SB in the organisational structure can enable it to perform its functions, its independence can help it perform better. Moreover, if it can evaluate operations during the audit process, this involvement can avoid the sense of powerless to correct existing problems that comes with retrospective audit. If the problem of having dedicated positions can be rectified, the supervisory personals can then dedicate more of their energy in the work of supervision. Experts can be appointed to help wherever there is lack of expertise. The dedication of the supervisory position and the enhancement of professional competence will be conducive to the performance of the supervisory mechanism.A.3.10. What is the motivation behind the forming of the AC?It is the emphasis on legitimacy. It is necessary to operate according to the regulations. It is obvious that such operations are good for the company.A.3.11. How, after its formation, should the AC interact with the internal audit department?The positions in the internal audit department are dedicated paid positions. The AC is led by the independent directors, whereas the SB is independent to the BoD. Once the AC is formed, hierarchically, the internal audit department will work under the AC; functionally, it remains to be seen how these institutions should work together.Case B (SB + AC):The general secretary of the BoD arranged the interview between author and interviewees. Before conducting the interviews with the supervisors and the members of the AC, Mr. Wang was interviewed as follows:B.1.1. Please describe the AC of your company.It works under the BoD. According to the constitutions of the company, it audits the operations of the whole company and the performance of the higher management. Its goal on financial audit is the same as that of the SB.B.1.2. Since the goals of the AC and the SB are the same, is there overlap between their functions? Has there been any consideration on the cost of supervision? How do they share the workload of supervision?The SB publishes its supervisory report biannually, and is mainly retrospective supervision; so theoretically, there is a need to increase progressive and concurrent supervisions. As there is the additional supervisory institution, I suppose the scope of supervision can be widened. Our company has not yet looked into the issue of the cost of supervision, probably because the supervisory function of the AC has not yet been fully realised, and there is no monetary cost for the SB. Currently, there are two stakeholders’ SB members, who are paid nothing other than their salaries for their respective roles in the company. The stockholder SB member is appointed by the government, who receives his own salary from his own organisation. The company does not need to pay these members for their supervisory work. The company only needs to pay the independent directors. It is a fixed sum determined by the General Assembly Meeting. The independent directors mainly attend the meetings of the BoD, and they tend to take the viewpoints of the minor and medium stockholders in their advice during the decision making process of the meetings of the BoD. On the other hand, the SB tends to take the viewpoints of the major stockholders in their retrospective supervision on the operations of the company. The functions of the two institutions are different.B.1.3. How does the SB operate?Its operation is simple. It does not operate much since its formation. Currently, it only reviews the financial and audit reports before the meetings, and discuss in their own meetings if there is any major problem. Apart from these, it does not perform any day-to-day supervision. Its focus is not the same as the internal audit department. The SB supervises mainly by reviewing reports, followed by oral enquiries if necessary.B.1.4. Which documents are provided for the members of the SB?Essentially, it is the same data available for the BoD before their meetings, such as the audit report, the BoD report, financial report, and the assessment of the performance of the higher management.B.1.5. Is there specific meeting agenda for the SB? Is there clear specification as to which documents should be reviewed by the members of the SB? Do its members meet before the meetings of the BoD?Yes, there is. I will give you a copy of the regulations on the meetings of the SB for your reference. This is compiled according to the responsibilities and procedures specified in the Company Act. The meetings of SB are held after the meetings of the BoD rather than before, but copies of relevant documents will be delivered by the Secretary of the BoD to the Directors and SB members ten days before the meeting of the BoD.B.1.6. Are there areas for improvement in the current supervisory system?There are three areas (concerning the SB) for improvement. First, it is not a dedicated role. Improvement is needed to improve the level of participation. Secondly, there is need to enhance professional competence, especially for the stakeholder members, who might not be able to understand financial reports. Thirdly, its membership should be a dedicated position. Currently, it is overseen by stakeholders, and it is difficult to realise its supervisory function. There is justifiable consideration behind having stakeholder members elected by the union, but there is the issue of independence. On the other hand, there is specific requirement on the professional level of the AC, and it consists of independent directors, so it is expected to be able to compensate the weakness of the SB.B.1.7. There are both the SB and the AC in Chinese system. How should these be organized in the organizational structure?The Chinese system has been through the history of the Three Old Institutions and the Three New Institutions. Combining with the global trends in the supervisory mechanisms, the special context of the Chinese system is formed. The Three Old Institutions (in state owned enterprises) are the Stakeholders’ Representatives’ Committee, the Management and Party Officers’ Committee. Our company was a Party-owned enterprise. The political atmosphere was a bit strong then. Now under the system of market economy, the economic tone is stronger. Currently, it is a semi-state-owned-and-semi-private enterprise. These characteristics need to be further integrated to suit the specific culture of China.B.1.8. How should the supervisory function be enhanced in practice in the future?First the professional competence of the members needs to be improved. Then the supervisory culture of the enterprise needs to be improved, and an environment conducive to proper supervision needs to be formed. The fundamental issue of independence need to be resolved, otherwise it is difficult to realise the supervisory function.B.1.9. Are there informal meetings between the SB and the AC?No.B.1.10. How long is a meeting by either the SB or the AC?A meeting of the SB is usually about half an hour, and it never lasts longer than an hour. It usually checks if there is any problem and then follow the motion of the specified agenda and procedures rather than investigating deeply into any problem.In order to understand more about the operations of SB, Mr. Shen, Chair of the SB, was introduced by Mr. Wang for interview by the author as follows:B.2.1. There are both the SB and the AC in the Chinese system. What is your view on the functions and operations of these two institutions?I have not been the Chair of the SB for long, but I have been involved in the process of company transition. Currently, both institutions have been formed in our company. This is to comply with the requirement of the Company Act, and concerns the legitimacy of the conduct of both the company and the higher management according to the constitution of the company. In my opinion, the AC is a more microscopic viewpoint. As to me, I am Chairs of both the SB and the committee of the Union, so the conduct of both the company and the higher management should be reviewed for their legitimacy and rationality. The consideration of rationality is from the angle of the Union, but this should not conflict with legitimacy.B.2.2. Is it your recommendation to have two stakeholders’ representatives on the SB?Yes.B.2.3. Having both the SB and the AC, there is the possibility that their functions may overlap. What is your opinion on this issue?In my opinion, there is not much overlap. The independent directors mainly participate in the operations of the BoD. The SB is parallel to the BoD. It is an independent institution; whereas the AC observes the operations of the company from a microscopic angle.B.2.4. What are the focal points when you call for the meetings of the SB?First, it is the level of execution of the resolutions by the BoD after the General Assembly Meeting. Secondly, it is the supervision of the taking of major decisions by the BoD according to the Company Act, Stock Exchange Regulations and the constitutions of the company. Thirdly, it is the level of legitimacy of the conducts of the BoD and the higher management, supervised by the members of the SB.B.2.5. In your opinion, what is the level of professional competence of the SB regarding the auditing of the financial report?I myself am definitely not an expert. There are accounting professionals in the SB. As the SB needs to oversee financial reporting, this is mainly done by the member with expertise in accounting. If he raises any questions, other members will assist accordingly.B.2.6. Has the SB performed any supervision or interpretation about the assessments, including the internal auditing?The BoD is more mature in its operations in this regard. Since this term of service of mine (which is my first term), there have not been many questions raised. This is because the SB mainly supervises the BoD, and the BoD is the main decision making institution.B.2.7. How frequently does the SB interact with the management under the BoD?Not frequently, but I attend every meeting of the BoD.B.2.8. Your job description is the permanent supervisor. Do you hold any other post in the company?I am also the Chair of the union and the internal legal advisor. The latter is for the conveniences of internal operations even though the company has also appointed external legal advisors.B.2.9. In your opinion, what are the strengths and weaknesses of the current operations of the SB?Our company has gone through certain historic transitions. It transformed from a wholly state owned organisation to a semi-state-owned one by releasing its stocks to its stakeholders, so the strength of the SB is that it is more democratic, having a good people foundation. A strength and weakness is its members are both stakeholders and stockholders. There are members elected by the stockholders as well as by stakeholders, so the relationship with the BoD is not the simple relationship between the supervised and the supervisor. Hence, there are interactions before problems reach the explicit process of supervision in which a common ground is reached and problems solved or hidden. As to the weakness of the SB, the professional level of the members of the SB, including I myself, need to be improved to the international standard. This applies to both financial and management professions.B.2.10. Are there areas in the mechanism and interaction between the two institutions where improvements are needed?The interaction between the two institutions should collect more regularly the operational information of the company. The BoD does respect the SB, and does notify the SB in advance about new policies and resolutions. Improvements are needed in the understanding of day-to-day operations. Enhancement in this understanding can further pinpoint the source of problems. I personally do not understand much of the operations of the AC, and I suppose they have the same problem towards us. For instance, upon the call for meetings, the independent directors might not be able to grasp the day-to-day operations of the company, and there are considerations on the qualities of their members.B.2.11. How do you expect the two institutions to interact and cooperate?The AC consists of independent directors and it is expected that they will sing a different tune. In some respect, it is good to have different voices. Having everyone singing in accord is not necessary a good thing. It is also expected that the independent directors can bring in the benefits of external links. This is because what they have experienced and encountered is different from those of our internal staff. They should be allowed to utilise their advantages to bring positive assistance to the company. To sum up, it is expected that they will bring in new ideas and links to the external environment, utilising their resources to enhance the company.B.2.12. What is the standard of supervision?For instance, the financial reports are audited according to the earnings conditions, following the GAAP/IFRS, from structural items to practical items.B.2.13. Are you involved in appointing external auditors?No. It is determined by the BoD.B.2.14. In your opinion, what improvements are needed to realise the supervisory mechanism of corporate governance?To further enhance or perfect supervisory effectiveness and function, first the quality of the members needs to be improved. Secondly, more attention is needed on the understanding of the process of the operations of the SB. Thirdly, the viewpoint of the SB is somewhat macroscopic; efforts might be needed to deepen and refine its view to be able to identify problems in advance and act as a problem prevention mechanism.To understand the process behind the implementation of the AC, Mr. Xu, the AC’s Chair was introduced to the author by Mr. Wang, General Secretary of the BoD. The resulting interview with Mr. Xu was as follows:B.3.1. In your opinion, what is the reason behind the AC installation?I don’t think there is conflict between the SB and the AC. I think that the SBs in China’s enterprises have not yet attained the standard it should have been in theory. Perhaps it is because of this, or because of the different operations in different countries, that we have observed some differences between our operations and the French companies that we came in touch with. Their SB operates at a different level than ours. The BoD has to report to the SB, and does not execute their plans without the approval of the latter. Whereas in our system, both the BoD and the SB report to the General Assembly Meeting. The BoD does not require the prior approval of the SB for its operations. Such a difference in corporate structure may have affected the effectiveness of the CG functions.B.3.2. Now that you have both the SB and the AC, how should these two departments share their supervisory roles?Theoretically, there must be some point in introducing the AC from the Anglo-American model. There are several reasons why the SB has not functioned as expected. First, in the Chinese context, many things are just formalities. There is no actual cultural backing for supervision. The members of the SB might be wary that they would be shunned by the management and the colleagues if they try too hard. Without the backing of the proper cultural environment, they are powerless in supervision. Secondly, the members of the SB mostly take on the role on a part-time basis, so they are reluctant in involving in the actual processes of supervision, so they probably do not really understand the onus of supervision, and ended up reviewing the final reports only. The main reason, basically, is that they don’t really want to supervise. Therefore, work should be done on changing the culture. The management should value the supervisory functions, and provide the members of the SB with necessary data and documents, rather than preventing the latter’s involvement in the operations.B.3.3. What do you think the main focus of the financial supervision of the AC would be?It would be to abide by relevant laws and regulations. Their evaluation and selection of external auditors should be based on the latter’s reputation and track record.B.3.4. How do you think should the AC function?Currently, there are three members of the AC. Two of these are independent directors, and I am the only internal member. The operation of the AC should be led by the two independent directors to ensure the independence of the AC. I myself am the Chief Financial Officer overseeing financial reporting. I don’t think there is any regulatory concern over this, but if the independent directors think otherwise, we should follow their opinion, which account for two thirds of the AC. Also, current regulation dictates that more than half of the members of the AC should be independent directors, but I think it would be more in line with the consideration on the independence of the AC if all members would be independent directors.B.3.5. How should the AC operate?There is an internal constitution for the AC, so the AC should operate accordingly. The independent director should call for meetings. The members of the AC meet once a season, but there isn’t much communication amongst them otherwise.Secretary Mr. Wang: We have just formed our AC and its operation and promotion is still wanting. The convener is experienced (in auditing and supervision), and we expect him to direct us in the operations of the AC. We have focused on complying with the relevant regulations for the sake of being a listed company.B.3.6. Please elaborate on the relations between the AC and the internal audit in your company.Initially, the internal audit was under the direct control of the Managing Director. Now it is promoted to be directly under the BoD. Though both the AC and internal audit have the functions of auditing, each has its own emphasis. The internal audit focuses on the details such as the supervision of internal control, whereas the AC takes a more macroscopic view. In the future, the internal audit unit should be installed under the AC so as to facilitate their co-operations. My primary role is the Chief Financial Officer, which is supposed to be supervised (by the internal audit), yet I am also a member of the AC (which is above the internal audit), and this is somewhat unusual. There are only three employees in the internal audit. I think it is necessary to enhance its function. Now the regulation for this is in place, we should focus on its installation. This should start with the formation of a culture and mindset conducive to its proper operation to distil the sense of importance in the auditing functions and willingness of the colleagues in cooperating with auditing departments in enabling their proper operations.B.3.7a. What are the problems facing supervision?As the AC has just been installed, it is still not fully functioning as specified by the regulations and expectations, so it is difficult to say if there would be any further problem in its operation.B.3.7b. Is there any area in its three main functions of the AC, i.e., financial reporting, auditing and internal control, in which improvement is needed?The crucial point, theoretically, is to instill the mindset throughout the organization of the importance of supervision and to improve the quality of the auditing staff. The operation of the SB and the AC should focus on the levels specified by the regulations so as to identify problems. In the current operation, the SB mainly oversees the results rather than the processes, and the members do not really strive to perform properly as this is not their main roles in the company. It is lacking in the level of supervision of the processes and the level of support the company gives to supervision.B.3.8a. Does the members of the AC meet before the meetings of the BoD to review the reports? How does it overcome the neglects in supervising the processes?This is not done at the moment.B.3.8b. Will it be done in the future?The Chief Financial Officer stresses the importance of financial data, and the effect of internal control is shown in the data. The supervision of processes should have been done on a daily basis rather than waiting for the AC to evaluate it before the Board of Director meetings.(The Chief Financial Officer went to answer a phone call)Secretary Mr. Wang: Because of his unique position in the company, Mr. Xu needs to know the financial condition because of his main role as the Chief Financial Officer, and since he is also the Chair of the AC, it is not necessary for the AC to meet before the BoD’ meetings to know the situation of internal control. Actually, the financial unit itself provides certain level of daily control.

Notes

- 1. Section 111 para. 2 sent. 1 & 2 AktG.2. Section 171 para. 1 sent. 1 AktG.3. Sections 111 para. 2 sent. 3, 170 para. 1 & 2, 171 para. 1 AktG, No. 7.2.2 GCGC.4. Section 90 para. 1 AktG.5. Sections 118 para. 3 sent. 1, 124 para. 3 sent. 1, 171 para. 2 AktG.6. Section 112 AktG.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML