-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2018; 7(5): 153-159

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20180705.04

Return on Human Capital: Quantile Regression Evidence in Brazil 2003-2013

Wellington Ribeiro Justo1, Nataniele dos Santos Alencar2, Matheus Oliveira de Alencar2, Denis Fernandes Alves3

1Economic Department, URCA/PPGECON, UFPE, Brazil

2Rural Economic Department, MAER/UFC, Brazil

3Economic Department, PPGECO, UFRN/GETEDRU, Brazil

Correspondence to: Wellington Ribeiro Justo, Economic Department, URCA/PPGECON, UFPE, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper undertakes an empirical examination of rates of return on human capital in Brazil through the period of macroeconomic stabilization and crisis (2003-2013). An appropriate empirical strategy is to fit the earnings model using the quantile regression. Counterfactual analysis is considerate. The results aim that there is evidence for reducing inequality in rates of return to education in Brazil differently form last decade. There was also a decrease in the wage gap between genders.

Keywords: Earnings, Human capital, Inequality, Quantile regression, Counterfactual analysis

Cite this paper: Wellington Ribeiro Justo, Nataniele dos Santos Alencar, Matheus Oliveira de Alencar, Denis Fernandes Alves, Return on Human Capital: Quantile Regression Evidence in Brazil 2003-2013, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 7 No. 5, 2018, pp. 153-159. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20180705.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In the last 20 years, the developments countries have undergone a process of substantial reform, especially in economy. Following the international economic instability in the nines 70 and 80 of the past secular, a lot of economies implementers programs to solve external account imbalances and controlling high inflation rates. From the mid 1980s, many of these countries undertook unprecedented economic reforms involving trade liberalization, privatization of state companies, and the deregulation of financial, labor and goods markets. These reforms have been allowed very rapidly and give rise profound economic changes (Arbache, 2000).In the international literature, papers such are: Kats and Murphy (1992), Arbache (1998) between others have been showed that economics changes effects in the curt e and long terms in the labor market, especially in the increasing of the inequalities earnings between the works with higher and lower qualification and the increasing of the unemployment, between the works with lower qualification, in the development countries. However there are discrepancies in term of knowledge of effects these changes in development countries.In the point of view about theoretical outline researchers such are Murphy and Welch (1992), Juhn, (1999) between others have fundament in validity of Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) model to investigate the behavioral of returns of variables of human capital how results of structural changes in demand favorable to higher qualification works. Contrary to H-O model, researchers such are Robins and Gindling (1999) shows increasing in relative demand favorable to higher qualification works in development countries.Evidences to Brazil suggest increasing in returns of variables of human capital after economics reforms. Arbache (1999) try explicating the improving of increasing of inequality in Brazil in 90s. Other empirical approach used for treat variable return of human capital has been quintile regression models. Silveira Neto and Campelo (2003), Araújo Júnior and Silveira Neto (2004) between others has explore this methodology. Especially to analyses the behavioral of returns of human capital variable in Brazil after economic liberalization, to stand out Arabsheibani, Carneiro e Henley (2003).Justo (2006) examined the rates of return to human capital in Brazil through the period of macroeconomic stabilization and trade liberalization (1992-2002). The results aim that there were evidence for growing inequality in rates of return to education in Brazil.In the last perspective, this paper try improvement in term of literature completes some gap. Such are: works with recent dates, put important variables to control of human capital human and compare the return of human capital between men and woman and analyses the behavioral differentials of earnings between agricultural sectors in another in the economy. This paper worry, in the point of view theoretical and empirical, to analysis the impact of economic period in worked market. Estimate quantiles regressions of human capital to get the pictures of human capital in different points of earnings distribution in Brazil, using dates of Brazilian household surveys - PNAD (National Research of Sample household) for 2003, 2011 and 2013. This period includes the two governments of Luis Inacio Lula da Silva and part of President Dilma Rousseff's mandates before the crisis provoked by the economic policy that strongly affected the labor market and culminated in the impeachment process.The reminder of the paper is structured as follows: beside this introduction, in the next section shows some theoretical aspects about human capital. Section 3 does a descriptive analyses profile of human capital, considering years of schooling, old, years of experience, interaction term between years of schooling and years of experience, suggesting the idea of inequality at the different points of earnings distribution and inter regional of variables of human capital. Section 4 presents econometrics results and a counterfactual exercise. Section 5 concludes.

2. Empirical approach

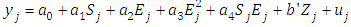

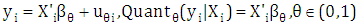

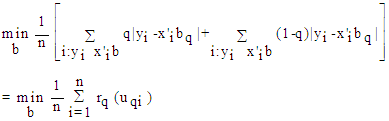

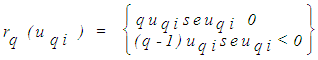

- In theory of human capital, Arabsheibani (1988) arguments that the investment in human capital increasing earning’s individuals, once that the acquisition of education increasing the productivity. Another explication is that education act only as a filter or a screen. Then arises an important question in returns of education studies, if in fact, formal education acts as a selection, separating the more able individuals (and educated) of the less able ( and educated). In the screening hypotheses, Arrow (1973) observes that at the point of hiring worker’s productivity is unknown to employers and argues therefore that employers use education as a proxy for latent productivity. In competitive sectors of the labour market returns to subsequent education after hiring will be lower. In non-competitive sectors of the labour market returns to subsequent education after hiring will be lower. It is therefore possible that the value of education as a screen may vary across the earnings distribution because of differing degrees of competition. In particular screening may be more important in the top of distribution, where insider power may be more important.According Arabsheibani, Carneiro and Henley (2003) the empirical literature on screening distinguishes between the weak form and strong form of the hypothesis (Psacharopoulos, 1979; Arabsheibani and Rees, 1998). The weal form states that employers will pay a higher initial salary to recruits with higher levels of schooling, but is agnostic about the shape of the subsequent experience-earnings profile. The strong form states that employers will continue pay high salaries even after observing working on the job, because education continues to enhance productivity as experience on the job rises. However, the experience-earnings profiles of an educated worker will converge over time that of a non-educated worker, as the original hiring “mistake” is gradually corrected. Psacharopoulos (1979) proposes what ha became known as P(sacharopoulos) test as a method of empirical investigation.With intention of investigate the returns of human capital tends and test the strong hypothesis using the model according Arabseheibani, Carneiro e Henley (2003). Assume that log earnings for individuals assume that log hourly earnings for individual i, yi , are determined according a Mincerian earnings function of the following form:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Estimation is by minimizing the sum of weighted absolute deviations and can be performed using linear programming methods (Buchinsky 1998). An estimated variance-covariance matrix for the chosen system of quantile regressions is obtained using a bootstrap re-sampling method. Quantile regression coefficients can be interpreted by considering the partial derivative of the conditional quantile with respect to a particular regressor. This equates to the marginal change in the θth conditional quantile due to a marginal change in the regressor. It is however important to note that sample individual who is in the θth conditional quantile may no longer remain in that quantile if his or her characteristic measured by the particular regressor changes. So, for example, rates of return to additional years of schooling or experience as captured by the estimated coefficients apply to an individual remaining in a particular conditional quantile.

Estimation is by minimizing the sum of weighted absolute deviations and can be performed using linear programming methods (Buchinsky 1998). An estimated variance-covariance matrix for the chosen system of quantile regressions is obtained using a bootstrap re-sampling method. Quantile regression coefficients can be interpreted by considering the partial derivative of the conditional quantile with respect to a particular regressor. This equates to the marginal change in the θth conditional quantile due to a marginal change in the regressor. It is however important to note that sample individual who is in the θth conditional quantile may no longer remain in that quantile if his or her characteristic measured by the particular regressor changes. So, for example, rates of return to additional years of schooling or experience as captured by the estimated coefficients apply to an individual remaining in a particular conditional quantile. 3. Data Source and Description

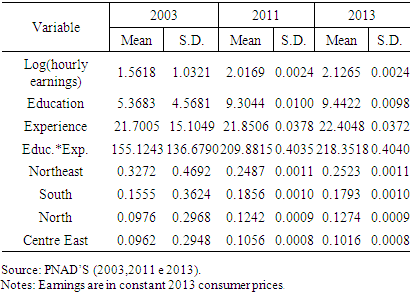

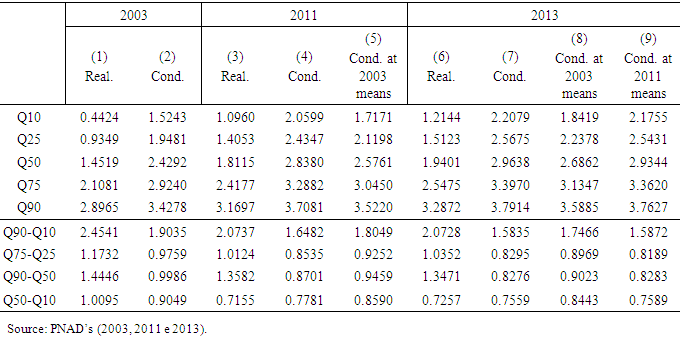

- In this paper use data drawn from de 2003, 2011 and 2013 Brazilian household surveys (Pesquisa Nacional por Amostragem de Domicílios, PNAD). The PNADs are a series of nationally representative household surveys conducted more or less annually since 1976, using a consistent methodology by the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica (IBGE). The sample is compost of individuals between the ages of 18 and 65, with non-null wage who report earnings and hours of work data and information on human capital and the other controls used for estimation purposes. Hourly earnings are defined as reported monthly earnings divided by 4.33 and then divided by reported weekly hours of work. Table 1 reports summary descriptive information for each year on log (hourly earnings), along with descriptive statistics on years of education, years of experience (defined as age - (6 + years of schooling)), educationxexperience and the regional dummies1.

|

4. Empirical Results

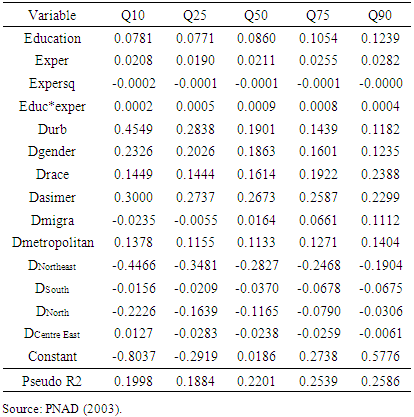

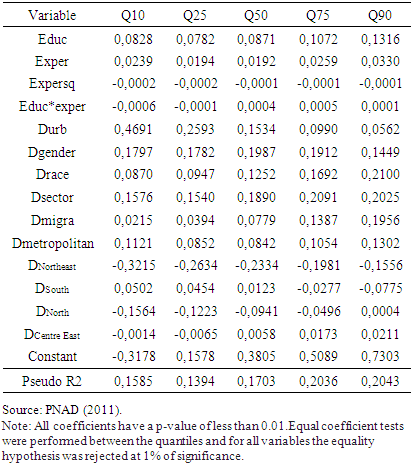

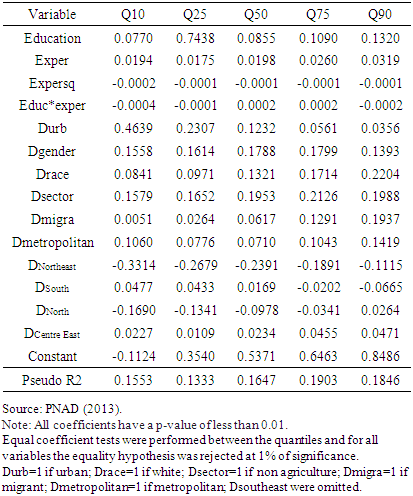

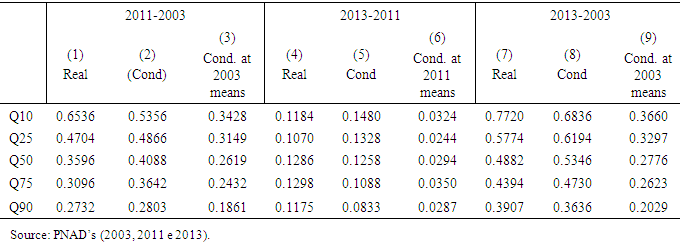

- Key results (coefficients a1, … ,a4) for earnings function estimates for 2003, 2011 and 20132 are presented in Table 2, 3 and 4. For each year the table shows simultaneous quantile regression estimates for the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th quantiles. The reported coefficients suggest considerable variation in the education-earnings and experience-earnings profiles at the different points in the earnings distribution. I shall discuss rates of return to education and experience shortly. The education-experience interaction coefficient is negatively signed and statistically significant (at 1%) at the 10th, 25 th and positively sample mean and for the 75th and 90th conditional quantiles for all period. This result suggests that in all period 2003-2013s for those at the very bottom of the earnings distribution formal education appears to have acted as a signal for innate ability rather than provided human capital unlike for it lies from the middle to the top of the distribution. Experience-earnings profiles appear to converge, albeit slowly, after initial. Similar results were meted for Arabsheibani, Carneiro and Henley (2003) for 1988-1998 periods.Returning to discussion of schooling and experience returns, by Table 2, 3 and 4 é possible observes some regularity. First, with respect to return, notes that it increasing in long of distribution and stability over the years. The differences between quantile (0.1) and (0.9) oscillate by (5.07%) in 2003 and (6.86%)3 in 2013. Other regularity is the increasing of return of education for quantile (0.9) in all period. This result suggest that a despite of increasing of people with more schooling there are rise the return for this group indicating um increasing in relative demand for workers with this profile. However, the return to those at the top of the distribution is much lower than in the previous decade as shown by Justo (2006). This indicates that education has been contributing to the reduction of inequality over time.

|

|

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

- This paper, has conducted an empirical investigation of the impact of schooling and experience across the earnings distribution for Brazilian workers over the period of the two governments of Luis Inacio Lula da Silva and part of President Dilma Rousseff's mandates before the crisis provoked by the economic policy that strongly affected the labor market and culminated in the impeachment process, through of quantile regression estimates of human capital. Overall results point to improved forces of competition in the labor market particular. This is particularly so because there appears to have been a shift in the role of educational qualifications from rationing or screening workers into better paid jobs towards education being rewarded because of their inherent association with higher productivity. This appears to be particularly the case in the top and bottom of the distribution and in all years. With this results then would expect to find string evidence for decrease earnings inequality. This has been a consequence of macroeconomic politic in Brazil. A possible explication is that the absence of improvements in levels of human capital has been occurred and has been contributed for narrowing the wage inequality. Between 2003 and 2013, period of growth public spending on social policies, there are improvements in the wage but the increasing is higher to workers at the bottom than to top of distribution earnings. Improvements in levels of endowed characteristics and human capital characteristics occurred but were of most benefit to the less well paid. This period appears to have stimulated the acquisition of human capital for the less well paid. Higher rates of return, combined with an increased recognition that educational qualifications are of inherent value rather than of use purely as a signaling device, may well have stimulated increased human capital investment, alongside government and private willingness to pay.There are indication too point to relative more importance of participation in agriculture sector in the relative unfavorable wage comparative to other economic sectors. This is, to individuals in the top of earnings distribution is less important belong or not in agriculture sector. The wage gap between the workers, in agriculture sector and other sectors, at the higher quantiles narrowing across the ten years analyzed indicating possibilities of technologies changes in this sector after the reforms.A possible extension this paper would put more controls variable allowing deep the investigation of dispersion of inter-sectors wage, gender and migrate.

Notes

- 1. The Southeast was the reference region.2. President Lula's warrant expired in 2010. But in that year there is no PNAD, because it was used in 2011. During that period, there was the international financial crisis.3. Values calculated by: value%= 100*[exp (coef.) – 1], with date of Table 2 and 4.4. Idem note 2.5. Idem note 2.6. To more details about this, see Santos Júnior (2002) and Justo and Silveira Neto (2006, 2008).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML