-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2017; 6(2): 37-45

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20170602.01

Critical Evaluation of Small Business Financial Strategies in Nigeria: A Panel Study

1Department of Banking and Finance, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

2Department of Accountancy, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Daibi W. Dagogo, Department of Banking and Finance, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This article evaluates the application of various financial strategies in small business in Nigeria, using panel study. The study was predicated upon the growing problem of financial dualism on account of the need to converge financial policies of large corporations and small enterprises. The study concentrates on financing strategies and identified five broad-band strategies for financing small businesses: debt, external equity, convertible preference capital, retained earnings, and financial bootstrapping. Fixed effect panel data regression models were formulated with each of the financing strategies serving as independent variable. The motive was to identify the contribution of each variable towards a suitable performance indicator for small businesses. To that extent, return on capital employed (an accounting-based indicator) and enterprise value (market-based indicator) were preferred. This further implied the formulation of two models, with two separate dependent variables (ROCE and NAV) while having the same set of independent variables. The results were evaluated wholly and individually using F-test and t-test respectively. Rejection criterion was set at p≤0.05. 400 data units were generated from a cross section of twenty small businesses spread in major cities, especially, in the southern region of Nigeria, and for a time period of twenty years, resulting in 20 by 20 panel study. It was found that financial bootstrapping strategy offers the most impact on small business financing. It was concluded that the emerging pecking order appears thus: financial bootstrapping, retained equity, external equity, convertible preference capital, and finally, debt capital. This was slightly subverted in the case of ROCE where debt financing ranked second on account of the inclusion of working capital in determining ROCE.

Keywords: Financial bootstrapping, Panel study, Convertible preference capital, External equity capital, Small and medium enterprises development agency of Nigeria (SMEDAN)

Cite this paper: Daibi W. Dagogo, John Ohaka, Critical Evaluation of Small Business Financial Strategies in Nigeria: A Panel Study, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 6 No. 2, 2017, pp. 37-45. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20170602.01.

Article Outline

1. Background

- Small businesses are an indispensable component of Nigeria’s economy. Traditionally, small businesses are the forerunners of industrialization. It is no longer news that small businesses create employment, contribute to the gross domestic product (GDP), promote rising quality of life of the people essentially by enhancing upward movement from low to medium income class, reduce poverty, and form the stepping stone for the establishment of major industrial organizations leading to industrialization of the society. For instance, industrialization which is the process of building up a nation’s capacity to convert raw materials and other inputs to finished goods, involves activities in craft, mining, processing, and manufacturing. Anyanwu et al (2003). The pre-independence period of Nigeria featured considerable craft industries involving artifacts of wood, brass and bronze, leather, textiles, iron works, pottery, canoe carvings, bronze works, and embroidery. These industries featured at close proximity with the available raw materials. All of these were pioneered by traditionally local businesses, which were undoubtedly small-sized (Dagogo, 2014).However, the superior competition from western industrialists with imperialist intentions reduced these local businesses to mere craft industries barely fit for collection of industrial raw materials for export. The need then arose for valorization, the initial process of removing waste matter, improving the quality, and converting the raw materials or produce into a form that was easier to export. Again, the magnitude, sophistication and capacity of the demand for these valorized raw materials were beyond the capacity of the local business people to embark upon not only because they did not have the administrative and managerial acumen but also because they cannot even acquire the technology required. Besides, the imperialist regime was not ready to encourage entrepreneurship among Nigerians, as they considered it as an instrument of economic emancipation and empowerment. It might be too unhealthy to do so if they must continue to lord over the Nigerian state. It turned out that the owners and operators of our indigenous craft industries became employees of large-sized expatriate-owned palm oil mills, groundnut crushing mills, cotton ginneries, oil seed mills, rubber mills, power-driven sawmills as well as finished goods factories like printing, publishing, baking, furniture works, etc. The merchandising sector, dominated by foreigners (Europeans and Asians) also created employment incentives for the abandonment of our indigenous crafts (Kirk-Greene & Rimmer 1981; Onyemelukwe, 1983; Dagogo, 2014).Events changed in the post-colonial era, and swiftly so in the oil boom era when Nigerians took up the management of these industrial and commercial establishments, particularly with the booster from Nigerian Enterprises Promotion Decree of 1972. With all the encouraging policies and programmes aimed at increasing the participation of Nigerians in entrepreneurship, not only to grow small businesses but also to see same sustained and harvested, not much was achieved. Some scholars attributed it to poor management, others inferred low demand capacity, yet some claimed technology was responsible. While admitting the views of Sanusi (2001) and Dagogo (2009) about the holistic nature of the problem, this paper takes keen interest in the inherent financial implications of the problem.

2. Statement of the Problem

- Small businesses are generally characterized as entrepreneurial and growth firms. A small firm that fails to transform into large firm auspiciously within, say, seven years, has itself failed. Besides, business failure is not exclusion to companies that collapse but also includes those that fail to grow (Dagogo, 2006). Decision making in business largely ensures sustainable market, production efficiency, and financial optimality (in financing, investing, liquidity and dividend). The complexities of these decisions often differ according to the size and nature of firm. With small businesses, the decisions lie in very few and occasionally inexperienced hands, a step that reduces the real time but exposes firms to adverse selection problems and moral hazards arising from suboptimal or hasty decisions. These decisions are undoubtedly the basis for the firm’s financial strategies. Little wonder, problems associated with financial strategies have been identified as some of the major causes of small business failure (David, 1995; Smith, 2013). Besides, the peculiarities of small businesses in relation to financial policies, objectives, and strategies have increasingly strengthened scholarly investigations in financial dualism (Ofonyelu 2013, Shem & Atieno 2001). It is the impact of these peculiar decisions on small business successes that occasioned the evaluation of financial strategies, particularly on financing decisions.Two hypotheses were formulated on the premises of the following question: Do small business financial strategies significantly manifest an ordered sequence? Above question gave rise to three tentative constructs: First, small business financial strategies do not significantly manifest a structured sequence in order to increase their enterprise values. Second, small business financial strategies do not significantly manifest any ordered sequence in order to increase their return on capital employed.

3. Literature Review

- In this review, no significant attempt was made to detail the onerous or minute differences between small business and the widely accepted concept of SME. First, it is necessary to acknowledge that both classifications are closely related to the extent that they do not require further differentiation or dualistic considerations in management, fiscal incentives, financing windows, investment opportunities technology fragility, competition and market sophistication. The opportunities, problems, and challenges of both categories are grossly alike. a. Small Business in NigeriaDagogo (2014) and Mike (2010) describe SMEs as ubiquitous and heterogeneous in nature with a maximum asset base of

million excluding land and working capital; total capital employed of not less than

million excluding land and working capital; total capital employed of not less than  million, employment of not less than 10 persons and not exceeding 300, and annual revenue of not less than

million, employment of not less than 10 persons and not exceeding 300, and annual revenue of not less than  million. Now, the difference is with the upper limits as a result of the inclusion of medium-sized enterprises in the case of SMEs, and for this study, we adopted an upper limit of

million. Now, the difference is with the upper limits as a result of the inclusion of medium-sized enterprises in the case of SMEs, and for this study, we adopted an upper limit of  million asset base and 100 employees, which represent a slight upward adjustment of SMEDAN’s 2010 benchmark, notably in line with recent changes in economic indices. Characteristically, small businesses are the essence of Nigeria’s financial dualism, as they inevitably secure funds from informal capital markets that leave them with the risk of making hard choices between mutually exclusive offers such as convenient access and low cost of capital. The formal capital market (registered and regulated) appears too unreachable in spite of the robust intervention and concession policies for small businesses, driven by the desire to stimulate the economy. For instance, the awesomeness of the 2004-2006 banking consolidation was measured by the strength of banks to serve industries better and to deal with the increasing complexities and nuances of small firms (Dagogo & Okorie, 2014; Nwankwo 2013). More than ten years after, the banks are expectedly better intermediaries with respect to transaction cost efficiency, transformation of risk and more importantly, transformation of short term liquidity to long term assets (Greenbaum & Thakor, 2007).In the past, Nigeria’s small business sector has been in a state of comatose in spite of several recommendations to improve its weaknesses caused by factors brought against itself, against it by the actions or inactions of government, and against it by society (Dagogo, 2015). These factors appeared too insurmountable in the past, and they include appropriate financing, market, competition, technology, innovation, infrastructure, and institutions. Recently, this sector has been identified as one of the critical drivers of the achievement of vision 20-2020, i.e. to launch Nigeria to the top 20 economies in the world by the year 2020. Accordingly, government started out with a microfinance policy framework that is aimed at creating sustainable financial intermediation for the class of enterprises that are not adequately served by the mainstream financial system. Secondly, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) launched the small and medium enterprises equity investment scheme (SMEEIS) in 2001 in response to the need to transform the economy through SMEs. Here, banks were persuaded to set aside 10 percent of their profit after tax for equity investment in SMEs. The scheme was fraught with poor participation and utilization of the funds. It was discontinued in 2009 and outstanding funds were transferred to Bank of Industry for the benefit of microenterprises (CBN, 2011).Thirdly,

million asset base and 100 employees, which represent a slight upward adjustment of SMEDAN’s 2010 benchmark, notably in line with recent changes in economic indices. Characteristically, small businesses are the essence of Nigeria’s financial dualism, as they inevitably secure funds from informal capital markets that leave them with the risk of making hard choices between mutually exclusive offers such as convenient access and low cost of capital. The formal capital market (registered and regulated) appears too unreachable in spite of the robust intervention and concession policies for small businesses, driven by the desire to stimulate the economy. For instance, the awesomeness of the 2004-2006 banking consolidation was measured by the strength of banks to serve industries better and to deal with the increasing complexities and nuances of small firms (Dagogo & Okorie, 2014; Nwankwo 2013). More than ten years after, the banks are expectedly better intermediaries with respect to transaction cost efficiency, transformation of risk and more importantly, transformation of short term liquidity to long term assets (Greenbaum & Thakor, 2007).In the past, Nigeria’s small business sector has been in a state of comatose in spite of several recommendations to improve its weaknesses caused by factors brought against itself, against it by the actions or inactions of government, and against it by society (Dagogo, 2015). These factors appeared too insurmountable in the past, and they include appropriate financing, market, competition, technology, innovation, infrastructure, and institutions. Recently, this sector has been identified as one of the critical drivers of the achievement of vision 20-2020, i.e. to launch Nigeria to the top 20 economies in the world by the year 2020. Accordingly, government started out with a microfinance policy framework that is aimed at creating sustainable financial intermediation for the class of enterprises that are not adequately served by the mainstream financial system. Secondly, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) launched the small and medium enterprises equity investment scheme (SMEEIS) in 2001 in response to the need to transform the economy through SMEs. Here, banks were persuaded to set aside 10 percent of their profit after tax for equity investment in SMEs. The scheme was fraught with poor participation and utilization of the funds. It was discontinued in 2009 and outstanding funds were transferred to Bank of Industry for the benefit of microenterprises (CBN, 2011).Thirdly,  billion SMEs credit guarantee scheme (SMECGS) was established in 2010 to fast track the development of the small business sub-sector and to set the pace for the industrialization of the economy by increasing the access of small businesses to credit. The novelty, here, is that credit risks, which inhibit lending to small firms are absorbed by CBN. Other special packages include:

billion SMEs credit guarantee scheme (SMECGS) was established in 2010 to fast track the development of the small business sub-sector and to set the pace for the industrialization of the economy by increasing the access of small businesses to credit. The novelty, here, is that credit risks, which inhibit lending to small firms are absorbed by CBN. Other special packages include:  billion SMEs restructuring and refinancing fund;

billion SMEs restructuring and refinancing fund;  billion cotton, textile and garments (CTG) funds for on-lending to SMEs engaged in the cotton, textile and garment value chain;

billion cotton, textile and garments (CTG) funds for on-lending to SMEs engaged in the cotton, textile and garment value chain;  billion NERFUND facility to re-align SMEs;

billion NERFUND facility to re-align SMEs;  billion Dangote Funds for MSMEs to stimulate participation in outsourcing and encourage partnership in private sector development in order to reduce importing of outsourced goods; Bank of Industry’s counterpart funding scheme; the youth enterprise with innovation in Nigeria (YOUWIN) programme, to encourage talents to start their own businesses; and several others. With every government administration attempting to initiate yet another unsuccessful financial programme, Lerner’s (2009) question “can bureaucrats help entrepreneurs?” becomes imperative.b. The Nigerian Financial SystemThe Nigerian financial system is a conglomerate of two financial markets, regulatory agencies, training institutions, independent parallel operators, all seeking to mobilize, allocate or utilize financial resources by dealing directly with the counterparties or serving as intermediaries between the surplus and deficit economic units (CBN 2011). The system has undergone several reforms aimed at strengthening its capacity, widening its scope and deepening its reach. For instance, the following instruments have been introduced recently: securitization and the decomposition of the bank lending function, dematerialization of share certificates and the electronic dividend payment system (NSE, 2015; SEC, 2015). Capital markets mobilize and transfer funds from surplus economic units to the deficit economic units, and banks are not only products of the intermediation process but are also instrumental to its development as underwriters or issuing houses. Similarly, consortium of banks or stand-alone banks establish private equity subsidiaries, which are the most appropriate funds for growing small businesses in line with the pecking order theory proposed by Myer (1984) and as observed by Dagogo, (2006). The money market is a set of institutions that handle the purchase of short term credit instruments like treasury bills and commercial papers (Samuelson and Nordhaus 2005). CBN exclusively regulates the activities of the money market operators through the following windows: open market operations (OMO), issue of prudential guidelines, setting minimum reserve ratios, issue or purchase of government securities, setting of minimum rediscount rates, and the management of external reserves. This goes to say that the role of banks in financing small businesses largely depends on the control exercised by CBN (CBN 2011).c. Financial Strategies in Small BusinessAccording to David (1995), strategic management is the art and science of formulating, implementing and evaluating cross functional decisions that enable an organization to achieve its objectives. The strategic management process consists of three stages: formulation, implementation and evaluation. Strategy formulation involves dreaming out a business vision, crafting business mission, identifying business external opportunities and threats, determining internal strength and weaknesses, establishing long term objectives, generating alternative strategies, and choosing particular strategy to pursue. Strategy implementation requires a firm to establish annual objectives, devise policies, motivate employees, and allocate resources to achieve formulated strategies. Strategy evaluation involves obtaining information relating to the effectiveness of the chosen strategies. It includes activities around reviewing external and internal factors that are the bases for current strategies, measuring performance, and taking corrective actions. This paper focuses on financial strategies evaluation for small businesses. Beginning from the 1990s, an unprecedented measure of awareness was created around strategic management highlighting its benefits. This awareness also gave rise to increased publication of journal articles focused on applying strategic management concepts in small businesses. A major conclusion of these articles is that a lack of strategic management knowledge is a serious obstacle for many small business owners (David 1995). Other problems include lack of sufficient capital, and day-to-day cognitive frame of reference. In all, it was agreed amongst researchers that while strategic management in small firms is more informal than in large firms, small firms that engage in strategic management outperformed those that do not (Smith 2013). In simple terms, strategy evaluation is an appraisal of business performance in terms of assets, profit, sales, return on investment, contribution margin, earnings per share, market value, etc. Upward changes in these indicators may be meaningless if they occur only in the short run and meaningful if they endure in the long run. Accordingly, Rumelt in David (1995) offered four criteria that could be used to evaluate strategies: consistency, consonance, advantage, and feasibility. For instance, a strategy must not present inconsistent goals and policies. A strategy must also represent an adaptive response to the external environment and to the critical changes occurring within it. Again, a strategy must not overtax available resources and/or create unsolvable sub-problems, i.e. it must be feasible in terms of physical, human, and financial resources of the enterprise. Finally, a strategy must provide for the creation and maintenance of a competitive advantage in a selected area of activity.The financial plan of a small business draws from the overall business plan that describes in clear terms the relevant external and internal elements involved in starting, growing, and sustaining the venture. Part of the business plan is the financial plan, and the entrepreneur is expected to have a complete evaluation of the profitability of the venture before embarking on a business. This assessment gives a preliminary hindsight of the viability, feasibility and profitability of the proposed business or continuing with the same line of business (Udoh, 2003). It also indicates how much money that will be needed to launch the business and meet short term financial needs, how to obtain the money and at what cost. There are traditionally, three areas of financial information that will be needed to ascertain the feasibility of the new venture: (1) expected sales and expense figures for at least the first three years; (2) cash flow figures for the first three years; (3) current balance sheet figures and pro forma figures for the first three years (Longenecker, Moore, and Petty 1997). Meanwhile the determination of the expected sales and expenses for each of the first twelve months and each subsequent year is based on the market information (Hisrich and Peters, 1998). The initial budgeting process may begin with an in-house expert where available or outsourced. The preparation of pro forma income statement begins with sales forecast in quantity and in Naira, followed by the percentage of sales method to determine values for other items in the statement. There are two broad financial objectives: profit maximization and shareholders wealth maximization. Others that are arguably less significant and convincingly dependent on the two above are liquidity, long term stability, growth, and corporate wealth maximization (Olowe, 2009; Ezirim, 2005).Overwhelming concern may have been shown in practice and in the academic world about the plight of small businesses and the need to grow them for sustainable development. However, little attention is paid to the strategies adopted by these firms. Studies in strategies have centred disproportionately on large and well-grounded firms. Financial decisions of small firms, as important as they are in defining competition, have not been given adequate attention. Again, financial analysis and planning, which represent basic features that support organizational strategy, are scarcely mentioned in small businesses, as they are considered money consuming. Surprisingly, planning activities are also dismissed as too tasking and non-core to the small business’ activity. Operators of small businesses are no doubt ignorant of the fact that well-crafted and well-executed financial strategy represents a path to competitive advantage. Financial strategies are goals, patterns or alternatives designed to improve and optimize financial management in order to achieve corporate targets (Lopez, 2006).Financial strategy consists of four interrelated kinds of decisions: investment, funding, working capital, and dividend (Ross, Westerfield & Jordan, 2000). Investment decisions deal with the allocation of capital to carry out investment opportunities that are valuable to the firm or that add value to the owners of the firm, while considering the risk inherent in receiving future cash flows. Funding decisions concern the specific mix of long term debt and equity that the company uses to finance its operations in order to maintain an optimal capital structure. Working capital decisions include the management of short term assets and liabilities in a way that ensures the adequacy of resources for company operations. Dividend decision is the action of management to determine what goes to shareholders after setting aside cash flow from previous year to finance investment opportunities or to pay shareholders without setting aside any amount with the hope of borrowing for the new investment opportunities, an action that results in increasing transaction cost and implication for stimulating the growth of share value within an acceptable capital structure mix. It is important for small businesses to seek the optimum combination of the four kinds of financial decisions, given its financial objective(s). Mallette (2006) recommends that an organization’s financial strategy must be evaluated and adjusted as frequently as operational strategy, and that such evaluation must be consistent with operations, needs and specificities of the business. A review of the description of financial practices of business is worthwhile. Valencia et al (2006) studied financial practices of Mexican firms in relation to the firm characteristics, finding that enterprises establish optimal leverage ratio, use investment evaluation techniques, practice result-based management measured by return on investment ROI) rather than economic value added (EVA), and apply financial ratios particularly to appraise profitability. Closely related is the empirical evidence from Jog & Srivastave (1994) which looked at financial decision-making processes and techniques employed by Canadian companies in solving problems of capital budgeting, financing (costs and sources), and dividend. They found that investment decisions are closely related to funding opportunities, and that they employ internal rate of return (IRR) and net present value (NPV) in capital budgeting decision. They also found that most Canadian companies determine an optimal debt and equity ratio. Concerning dividend decisions, present and future earnings represent critical variables considered. Similarly, Pohlman et. al. (1988) and Lazaridis (2002) investigated company information and determination of cash flow, and found that a significant number of companies use subjective methods to forecast cash flows. Kamath (1997) analyzed long term funding decisions in large corporations and found that statistically significant number of them do not maintain objective criteria in setting preferred capital structure. They also showed that the main issues in financing decisions are those related to maintaining financial flexibility and long term survival. But truly, that was for large corporations. The question is: does that apply to small businesses or should we arbitrarily estimate measure for small businesses given the benchmark of large corporations? Zopounidis and Doumpos (2002) examined the Multi-Criteria Decision Aid (MCDA) technique, which solves financial decision making problem by evaluating corporate performance, investment, and credit problems.Again, there have been researches on the analysis of financial decisions and their impacts on creating value for investors. Escalera and Herrera (2006) studied the relationship between financial decision making and economic value creation in Mexican companies. They found that companies that use supplier financing are more likely to create economic value as long as they do not have collection problems, and that investment decisions must take inventory into account. However, their study was based on small business owners’ perceptions of the importance of decisions, excluding the study of variables such as business performance, competitiveness and market reactions. Also, Winborg and Landstrom (2000) examined small business managers’ resource acquisition behaviors, and identified bootstrapping as major asset acquisition strategy. Two things are closely evident in the review above: first, corporate finance research is scarcely centred on financial strategies of small businesses; and second, most studies adopt causal models to explain the relationships between collection of strategies and key indicators rather than evaluation of decomposed strategies and their effects on market-driven and fundamental indicators. This paper fills the gap identified by evaluating the impact of financial strategies on return on capital employed and enterprise value of small businesses in Nigeria.d. Evaluation TechniquesThere are evaluation methodologies for customized or general applications. Some were originally developed for specific programmes, and later adapted for general application. For small businesses, the following factors determine the choice of appropriate evaluation technique: affordability, ease of application, efficiency, comparability of results or outcomes, compactness, and brevity of result. Besides, there are evaluation techniques traditional to business that have standardized usage and are applied in measuring and comparing outcomes. These are financial ratios, capital budgeting techniques, indexes etc. Respecting ratios, the following groups exist: liquidity, profitability, activity, and leverage (Pandey, 2002; Schmidlin, 2014). Each group in some partial synchrony evaluates the four key decision areas in finance namely: liquidity, dividend, investment and financing. There are other evaluation models, developed and frequently used by multilateral agencies, now available for use by any organization. One of such models is the project logical framework (Logframe) which allows planners to sneak into the impact of a project (including business operations). Logframe was developed in 1969 for the USAID and has been widely used by multilateral donor organizations like DFID, UNDP and EC (Dagogo, 2015). It takes the form of a four-by-four project table. The four rows describe four different types of events that take place as a project is implemented: Activities, outputs, purpose and goal. The four columns provide different types of information about the events in each row: narrative description of event, objectively verifiable indicators (OVIs) means of verification (MoV), and assumptions or contextual variables. It is most useful for pre-project implementation impact assessment, and its results rely strongly on assumptions that may be abused by overzealous evaluators (Udoh, 2000). Result-based management is another model which uses feedback loop to achieve strategic goals. People that contribute to results usually detail out their inputs and outputs showing how they contribute to outcome. This outcome may be a physical output, a change, an impact or a contribution to a higher level goal. This framework is largely used in government and not-for-profit organizations where purely financial measures are not the key drivers (Udoh, 2000).

billion Dangote Funds for MSMEs to stimulate participation in outsourcing and encourage partnership in private sector development in order to reduce importing of outsourced goods; Bank of Industry’s counterpart funding scheme; the youth enterprise with innovation in Nigeria (YOUWIN) programme, to encourage talents to start their own businesses; and several others. With every government administration attempting to initiate yet another unsuccessful financial programme, Lerner’s (2009) question “can bureaucrats help entrepreneurs?” becomes imperative.b. The Nigerian Financial SystemThe Nigerian financial system is a conglomerate of two financial markets, regulatory agencies, training institutions, independent parallel operators, all seeking to mobilize, allocate or utilize financial resources by dealing directly with the counterparties or serving as intermediaries between the surplus and deficit economic units (CBN 2011). The system has undergone several reforms aimed at strengthening its capacity, widening its scope and deepening its reach. For instance, the following instruments have been introduced recently: securitization and the decomposition of the bank lending function, dematerialization of share certificates and the electronic dividend payment system (NSE, 2015; SEC, 2015). Capital markets mobilize and transfer funds from surplus economic units to the deficit economic units, and banks are not only products of the intermediation process but are also instrumental to its development as underwriters or issuing houses. Similarly, consortium of banks or stand-alone banks establish private equity subsidiaries, which are the most appropriate funds for growing small businesses in line with the pecking order theory proposed by Myer (1984) and as observed by Dagogo, (2006). The money market is a set of institutions that handle the purchase of short term credit instruments like treasury bills and commercial papers (Samuelson and Nordhaus 2005). CBN exclusively regulates the activities of the money market operators through the following windows: open market operations (OMO), issue of prudential guidelines, setting minimum reserve ratios, issue or purchase of government securities, setting of minimum rediscount rates, and the management of external reserves. This goes to say that the role of banks in financing small businesses largely depends on the control exercised by CBN (CBN 2011).c. Financial Strategies in Small BusinessAccording to David (1995), strategic management is the art and science of formulating, implementing and evaluating cross functional decisions that enable an organization to achieve its objectives. The strategic management process consists of three stages: formulation, implementation and evaluation. Strategy formulation involves dreaming out a business vision, crafting business mission, identifying business external opportunities and threats, determining internal strength and weaknesses, establishing long term objectives, generating alternative strategies, and choosing particular strategy to pursue. Strategy implementation requires a firm to establish annual objectives, devise policies, motivate employees, and allocate resources to achieve formulated strategies. Strategy evaluation involves obtaining information relating to the effectiveness of the chosen strategies. It includes activities around reviewing external and internal factors that are the bases for current strategies, measuring performance, and taking corrective actions. This paper focuses on financial strategies evaluation for small businesses. Beginning from the 1990s, an unprecedented measure of awareness was created around strategic management highlighting its benefits. This awareness also gave rise to increased publication of journal articles focused on applying strategic management concepts in small businesses. A major conclusion of these articles is that a lack of strategic management knowledge is a serious obstacle for many small business owners (David 1995). Other problems include lack of sufficient capital, and day-to-day cognitive frame of reference. In all, it was agreed amongst researchers that while strategic management in small firms is more informal than in large firms, small firms that engage in strategic management outperformed those that do not (Smith 2013). In simple terms, strategy evaluation is an appraisal of business performance in terms of assets, profit, sales, return on investment, contribution margin, earnings per share, market value, etc. Upward changes in these indicators may be meaningless if they occur only in the short run and meaningful if they endure in the long run. Accordingly, Rumelt in David (1995) offered four criteria that could be used to evaluate strategies: consistency, consonance, advantage, and feasibility. For instance, a strategy must not present inconsistent goals and policies. A strategy must also represent an adaptive response to the external environment and to the critical changes occurring within it. Again, a strategy must not overtax available resources and/or create unsolvable sub-problems, i.e. it must be feasible in terms of physical, human, and financial resources of the enterprise. Finally, a strategy must provide for the creation and maintenance of a competitive advantage in a selected area of activity.The financial plan of a small business draws from the overall business plan that describes in clear terms the relevant external and internal elements involved in starting, growing, and sustaining the venture. Part of the business plan is the financial plan, and the entrepreneur is expected to have a complete evaluation of the profitability of the venture before embarking on a business. This assessment gives a preliminary hindsight of the viability, feasibility and profitability of the proposed business or continuing with the same line of business (Udoh, 2003). It also indicates how much money that will be needed to launch the business and meet short term financial needs, how to obtain the money and at what cost. There are traditionally, three areas of financial information that will be needed to ascertain the feasibility of the new venture: (1) expected sales and expense figures for at least the first three years; (2) cash flow figures for the first three years; (3) current balance sheet figures and pro forma figures for the first three years (Longenecker, Moore, and Petty 1997). Meanwhile the determination of the expected sales and expenses for each of the first twelve months and each subsequent year is based on the market information (Hisrich and Peters, 1998). The initial budgeting process may begin with an in-house expert where available or outsourced. The preparation of pro forma income statement begins with sales forecast in quantity and in Naira, followed by the percentage of sales method to determine values for other items in the statement. There are two broad financial objectives: profit maximization and shareholders wealth maximization. Others that are arguably less significant and convincingly dependent on the two above are liquidity, long term stability, growth, and corporate wealth maximization (Olowe, 2009; Ezirim, 2005).Overwhelming concern may have been shown in practice and in the academic world about the plight of small businesses and the need to grow them for sustainable development. However, little attention is paid to the strategies adopted by these firms. Studies in strategies have centred disproportionately on large and well-grounded firms. Financial decisions of small firms, as important as they are in defining competition, have not been given adequate attention. Again, financial analysis and planning, which represent basic features that support organizational strategy, are scarcely mentioned in small businesses, as they are considered money consuming. Surprisingly, planning activities are also dismissed as too tasking and non-core to the small business’ activity. Operators of small businesses are no doubt ignorant of the fact that well-crafted and well-executed financial strategy represents a path to competitive advantage. Financial strategies are goals, patterns or alternatives designed to improve and optimize financial management in order to achieve corporate targets (Lopez, 2006).Financial strategy consists of four interrelated kinds of decisions: investment, funding, working capital, and dividend (Ross, Westerfield & Jordan, 2000). Investment decisions deal with the allocation of capital to carry out investment opportunities that are valuable to the firm or that add value to the owners of the firm, while considering the risk inherent in receiving future cash flows. Funding decisions concern the specific mix of long term debt and equity that the company uses to finance its operations in order to maintain an optimal capital structure. Working capital decisions include the management of short term assets and liabilities in a way that ensures the adequacy of resources for company operations. Dividend decision is the action of management to determine what goes to shareholders after setting aside cash flow from previous year to finance investment opportunities or to pay shareholders without setting aside any amount with the hope of borrowing for the new investment opportunities, an action that results in increasing transaction cost and implication for stimulating the growth of share value within an acceptable capital structure mix. It is important for small businesses to seek the optimum combination of the four kinds of financial decisions, given its financial objective(s). Mallette (2006) recommends that an organization’s financial strategy must be evaluated and adjusted as frequently as operational strategy, and that such evaluation must be consistent with operations, needs and specificities of the business. A review of the description of financial practices of business is worthwhile. Valencia et al (2006) studied financial practices of Mexican firms in relation to the firm characteristics, finding that enterprises establish optimal leverage ratio, use investment evaluation techniques, practice result-based management measured by return on investment ROI) rather than economic value added (EVA), and apply financial ratios particularly to appraise profitability. Closely related is the empirical evidence from Jog & Srivastave (1994) which looked at financial decision-making processes and techniques employed by Canadian companies in solving problems of capital budgeting, financing (costs and sources), and dividend. They found that investment decisions are closely related to funding opportunities, and that they employ internal rate of return (IRR) and net present value (NPV) in capital budgeting decision. They also found that most Canadian companies determine an optimal debt and equity ratio. Concerning dividend decisions, present and future earnings represent critical variables considered. Similarly, Pohlman et. al. (1988) and Lazaridis (2002) investigated company information and determination of cash flow, and found that a significant number of companies use subjective methods to forecast cash flows. Kamath (1997) analyzed long term funding decisions in large corporations and found that statistically significant number of them do not maintain objective criteria in setting preferred capital structure. They also showed that the main issues in financing decisions are those related to maintaining financial flexibility and long term survival. But truly, that was for large corporations. The question is: does that apply to small businesses or should we arbitrarily estimate measure for small businesses given the benchmark of large corporations? Zopounidis and Doumpos (2002) examined the Multi-Criteria Decision Aid (MCDA) technique, which solves financial decision making problem by evaluating corporate performance, investment, and credit problems.Again, there have been researches on the analysis of financial decisions and their impacts on creating value for investors. Escalera and Herrera (2006) studied the relationship between financial decision making and economic value creation in Mexican companies. They found that companies that use supplier financing are more likely to create economic value as long as they do not have collection problems, and that investment decisions must take inventory into account. However, their study was based on small business owners’ perceptions of the importance of decisions, excluding the study of variables such as business performance, competitiveness and market reactions. Also, Winborg and Landstrom (2000) examined small business managers’ resource acquisition behaviors, and identified bootstrapping as major asset acquisition strategy. Two things are closely evident in the review above: first, corporate finance research is scarcely centred on financial strategies of small businesses; and second, most studies adopt causal models to explain the relationships between collection of strategies and key indicators rather than evaluation of decomposed strategies and their effects on market-driven and fundamental indicators. This paper fills the gap identified by evaluating the impact of financial strategies on return on capital employed and enterprise value of small businesses in Nigeria.d. Evaluation TechniquesThere are evaluation methodologies for customized or general applications. Some were originally developed for specific programmes, and later adapted for general application. For small businesses, the following factors determine the choice of appropriate evaluation technique: affordability, ease of application, efficiency, comparability of results or outcomes, compactness, and brevity of result. Besides, there are evaluation techniques traditional to business that have standardized usage and are applied in measuring and comparing outcomes. These are financial ratios, capital budgeting techniques, indexes etc. Respecting ratios, the following groups exist: liquidity, profitability, activity, and leverage (Pandey, 2002; Schmidlin, 2014). Each group in some partial synchrony evaluates the four key decision areas in finance namely: liquidity, dividend, investment and financing. There are other evaluation models, developed and frequently used by multilateral agencies, now available for use by any organization. One of such models is the project logical framework (Logframe) which allows planners to sneak into the impact of a project (including business operations). Logframe was developed in 1969 for the USAID and has been widely used by multilateral donor organizations like DFID, UNDP and EC (Dagogo, 2015). It takes the form of a four-by-four project table. The four rows describe four different types of events that take place as a project is implemented: Activities, outputs, purpose and goal. The four columns provide different types of information about the events in each row: narrative description of event, objectively verifiable indicators (OVIs) means of verification (MoV), and assumptions or contextual variables. It is most useful for pre-project implementation impact assessment, and its results rely strongly on assumptions that may be abused by overzealous evaluators (Udoh, 2000). Result-based management is another model which uses feedback loop to achieve strategic goals. People that contribute to results usually detail out their inputs and outputs showing how they contribute to outcome. This outcome may be a physical output, a change, an impact or a contribution to a higher level goal. This framework is largely used in government and not-for-profit organizations where purely financial measures are not the key drivers (Udoh, 2000). 4. Research Design, Models Formulation, and Hypotheses Testing

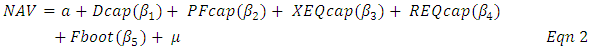

- The design adopted is panel study because time series and cross sectional data were employed. Twenty year time series data relating to financing decisions were collected from judgmentally determined cross-section of twenty small businesses operating in Nigeria without undermining the need to produce reliable and verifiable results. Sample size would have been greater but for the lean financial purse of the researchers, as data were collected from sample of small businesses spread across major cities particularly in southern and central Nigeria, ensuring that no single city enlisted more than two small businesses. This is to avoid dominance of any particular area or region, thus giving it a truly cross-country characterization. The dependent variables are return on capital employed (ROCE) and net asset value (NAV). Net asset value was estimated by using the market approach of net asset valuation model. The independent variables are debt capital, external equity capital, preference capital (or convertible capital), retained earnings, and financial bootstrap.Two panel data regression models were developed with ROCE and NAV as the dependent variables that are responsive to changes in financial strategies such as debt financing, preference capital (with conversion right), external equity, retained earnings, and financial bootstrapping. Estimating accounting values for bootstrapped finance was difficult as such values are spread across different facets of accounting, financial, production and marketing quantities. We were guarded by Winborg and Landstrom (2000), and Vanacker, Manigart, Meulemand and Sels (2009) to generate bootstrapping strategies and methods which became the basis for collecting five-point scale ordinal data ranging from ‘0’, representing ‘no use’ to ‘4’ representing ‘very high use.’ The categories are: joint utilization of facilities or virtual scaling, delaying payments, expediting receipts, purchase of used assets, minimizing investment in human assets, and futures contract. Accordingly, the first model evaluated the effect of financing decisions on returns on capital employed. This is preferred because of the difference between ROCE and earnings rate. The appropriate capital in the determination of ROCE includes working capital, a procedure we considered very useful in evaluating financing decision:

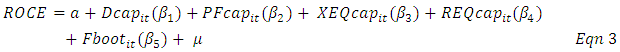

Where ROCE = return on capital employed; Dcap = debt capital; PFcap = preference capital; XEQcap = external equity capital, REQcap = retained equity capital, and Fboot = financial bootstrapping. The second model has net asset value as the dependent variable. This is the market value of assets and any other market-determined premium in relation to the value created by the firm, including estimable intangible assets. The market approach was preferred because it offers a reflection of the current value of net assets of the firm due to owners. Net asset was calculated by deducting total liabilities from the fair value or replacement value of total assets. This completes the attempt to use both accounting-based and market-based models of valuation.

Where ROCE = return on capital employed; Dcap = debt capital; PFcap = preference capital; XEQcap = external equity capital, REQcap = retained equity capital, and Fboot = financial bootstrapping. The second model has net asset value as the dependent variable. This is the market value of assets and any other market-determined premium in relation to the value created by the firm, including estimable intangible assets. The market approach was preferred because it offers a reflection of the current value of net assets of the firm due to owners. Net asset was calculated by deducting total liabilities from the fair value or replacement value of total assets. This completes the attempt to use both accounting-based and market-based models of valuation. Where NAV = net asset value; the independent variables are as defined in equation 1 above. In panel studies, equations 1 and 2 will be of form:

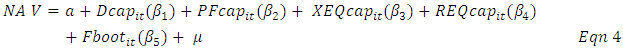

Where NAV = net asset value; the independent variables are as defined in equation 1 above. In panel studies, equations 1 and 2 will be of form:

Where a = intercept of the Y axis or the autonomous contribution to ROCE i.e. the value of ROCE when the values of all five independent variables are equal to zero. And μ is the error component of the multiple regressions associated with the ceteris paribus assumptions in economics. With regards to the panel data, the following assumptions were made: (a) all the heterogeneity characteristics of the cross-sectional intercepts are subsumed in one intercept value, allowing us to express each variable as a deviation from the variable’s mean. (b)

Where a = intercept of the Y axis or the autonomous contribution to ROCE i.e. the value of ROCE when the values of all five independent variables are equal to zero. And μ is the error component of the multiple regressions associated with the ceteris paribus assumptions in economics. With regards to the panel data, the following assumptions were made: (a) all the heterogeneity characteristics of the cross-sectional intercepts are subsumed in one intercept value, allowing us to express each variable as a deviation from the variable’s mean. (b)  and X’s are correlated. Where

and X’s are correlated. Where  is the error component and X’s are the regressors. Both assumptions strongly suggested the application of fixed effect (within group) estimator such that

is the error component and X’s are the regressors. Both assumptions strongly suggested the application of fixed effect (within group) estimator such that  . (Wooldridge, 2013; Gujarati, Porter and Gunasekar, 2012).

. (Wooldridge, 2013; Gujarati, Porter and Gunasekar, 2012).

Where i equals small businesses in the sample running from 1 to 20; and t equals time series data in each sample unit running from 1 to 20 years. This suggests a panel data analysis of 20 by 20 giving us 400 data units in the data set. The following tests were conducted: (a) F-test examined the overall effect of changes in the independent variables on the dependent variable (b) t-test took account of the strength of each independent variable in the same causation stated above. (Gujarati and Gujarati 2007).

Where i equals small businesses in the sample running from 1 to 20; and t equals time series data in each sample unit running from 1 to 20 years. This suggests a panel data analysis of 20 by 20 giving us 400 data units in the data set. The following tests were conducted: (a) F-test examined the overall effect of changes in the independent variables on the dependent variable (b) t-test took account of the strength of each independent variable in the same causation stated above. (Gujarati and Gujarati 2007).5. Results and Discussions

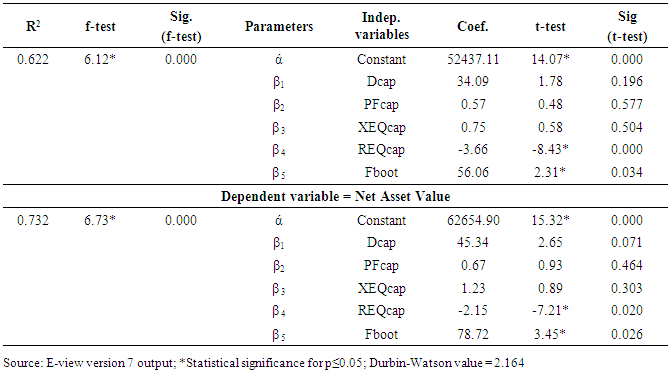

- The summary of the outcome of the panel study is presented in two parts in table 1 below. The first part shows the results of the fixed effect model for equation 3 while the second shows the results for equation 4.

|

6. Discussion

- First, the outcome of this study conforms to the long standing tradition of the financial logic respecting capital structure theory with its several versions and derivative. Financial leverage is a subject matter of capital structure theory and four approaches are well documented in the annals of finance including that for Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller (1958 and 1963) about capital structure indifference. The outcome of this study conforms to the argument that capital structure does matter, and that firms with increased financial leverage are likely to push their profit potential upward or increase their enterprise value. However, there are two issues that are worrying in this assertion. First, there is no clue as to the extent to which this upward movement of profit can get to with the aid of financial leverage, as it is well recorded that an optimal capital structure exists, beyond which profit may turn southward irrespective of additional leverage. Perhaps, the lack of clear statistical significance (p≤0.196 for ROCE and (p≤0.071 for net asset value) may be suggestive of the fact that small businesses should use financial leverage with caution. Second, it is also well acknowledged by scholars like Smith (2013), Dagogo (2009), Gomper & Sahlman (2002), Keown et al (1998), and Kamath (1997) that small businesses are likely to prefer equity capital at the early stages of enterprise development because the combined effect of operating and financial risks could render debt financing unattractive. Again, it is often stated by scholars that small businesses do better when they plough back early cash flows to finance growth but there is dissention as to what constitute the right proportion to plough back. Some argue for high dividend and others low dividend (Dagogo 2006; Pandey, 2005; Van Horne 2002; Keown et al 1998; Chew 2001; Black 1976). Others like Modigliani and Miller (1968) had issues with the concept of dividend policy relevance and argued that it is mere waste of time and resources. The negative outcome of this study clearly indicated that dividend decision does matter, as it probably represents the cheapest strategy to finance growth. For this reason, private equity investors appear to be more willing to stick out their funds for a long period before expecting returns. Finally, as shown above, financial bootstrapping strategy (involving a bit of do-it-yourself) increases earnings and net asset value (Bhide, 1992; Winborg and Landstrom 2000).

7. Conclusions and Implications

- After diligent analysis of the data and the findings that emerged, this study draws the following inference-based conclusions: that the financing strategies with the most attractive results in their order of importance are: financial bootstrapping, retained equity, external equity, convertible preference capital, and debt capital. For ROCE, the sequence may be altered to place debt in third place because of the inclusion of working capital finance in determining ROCE. This pecking order, the basis of our conclusion, should be applied only when the endogenous and exogenous variables are significantly similar to our assumptions in this paper. Undoubtedly, small businesses are largely private equity capital financed along with cost saving bootstrapping strategies. Dividend payout (whether high or low proportion) reduces growth and profitability profile of small businesses; and availability of multiple financing windows leads to liquidity optimality. Suffice to say, opportunity for positive cash flow is a challenge for small businesses particularly at growth stage. This alludes to the possibility of insolvency and rising risk of bankruptcy among small businesses, a phenomenon that is detrimental to private sector growth.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML