-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2016; 5(6): 247-260

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20160506.02

Evolutionary Dynamics of Auditing Regulation under a Program Theory Perspective

Federica De Santis

Department of Management, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Italy

Correspondence to: Federica De Santis, Department of Management, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Pushed by the global financial crisis and by the need to restore trust in corporate financial information and on the audit function, the EC has reformed the audit regulatory framework by issuing the statutory audit Directive 2014/56/EU and the associated Regulation n. 537/2014. Adopting a program theory perspective, this research aims to answer to three different questions: (1) What are the EC’s intended objectives that led to the issuing of the Statutory Audit Reform?; (2) What are the measures actually put in place at the EU level in order to reach these intended objectives? and (3) How these measures have been implemented within the Italian context and what are the main change that the new regulatory framework produced/is supposed to produce?. The study provides evidence in which way the measures of the audit reform and the EC’s intended objectives have been translated and applied in the Italian audit environment. The proposed analysis revealed that the EC’s measures intended to lead to the desired outcomes has been subject to more or less substantive changes within the regulatory process. Moreover, the Italian experience seems to suggest that some the measures enacted in order to reach an overall enhancement of audit quality and auditor independence, as well as a more dynamicity in the audit market, such as mandatory audit firm rotation and prohibition of NAS, do not have a direct and positive effect on real auditors’ independence nor on market openness. Further research is needed in order to assess if and how the Statutory audit reform will produce its intended outcomes when it will become completely effective in all the Member States of the EU.

Keywords: Auditing, Regulation, Harmonization of auditing, Program theory

Cite this paper: Federica De Santis, Evolutionary Dynamics of Auditing Regulation under a Program Theory Perspective, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 5 No. 6, 2016, pp. 247-260. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20160506.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Statutory auditing plays an essential role in providing credibility to companies’ financial information, as the users of financial statements consider the audit report as a guarantee of their reliability [15]. In validating the information disclosed by means of companies’ financial statements, therefore, statutory auditing ensures the efficient and effective functioning of capital markets [29]. One of the most relevant features that distinguishes the statutory audit from the overall practice of public accountancy is that it focuses on audits mandated by law and regulated by the state [1].The contemporary development of international auditing regulation is connected to the growing importance of international investors, who demand financial reports that are prepared and audited in accordance to generally accepted international standards [28]. Moreover, the current global financial crisis and the subsequent corporate collapses may be considered as a particularly interesting topic from the perspective of the statutory audit [29, 30]. Over the last fifteen years, indeed, the efforts to cope with as well as to prevent corporate financial scandals have resulted in substantial changes in the auditing regulatory framework and in the way in which auditors perform their work [32, 33]. Specifically, the audit regulation and the standard setting process have shifted from a national to an international level, moving from a doctrine of “liberalize the market” to one of “standardize the market”. The aim of this standardization process consists in establishing a common framework of rules and standards within which the audit market can operate [44, 29, 33].The Directive 2006/43/EC represented the first attempt in auditing standardization in Europe as it has been enacted in order to reach a high-level of harmonization of the statutory audit requirements [25]. Nonetheless, the financial crisis that commenced in 2007 has raised attention on the limits and limited capabilities of auditing as well as on the need to reform aspects of practice and regulation [29, 43]. The European Commission (EC) has thus published a Green Paper with the objective of initiate a real debate at the European level about the role and the governance of auditors as well as the possible changes, which could be foreseen in this domain1. Stemming from the standpoints on which the Green Paper has been constructed, the EC has reformed the audit regulatory framework by issuing the statutory audit Directive 2014/56/EU and the associated Regulation n. 537/2014 that specifically refers to the statutory audit of Public Interest Entities (PIEs).In this scenario, several authors have claimed for more research consideration about the global regulatory audit arena and the peculiarities of different contexts and nations [29, 8, 42, 41]. It becomes of interest, therefore, to analyse how the auditing regulatory landscape has evolved in Europe as well as in a specific national context. This study, therefore, focuses on the evolutionary dynamics of the audit regulation, with reference to the European Union context, in general, and the Italian context, in particular.Adopting a program theory perspective, this research aims to answer to three different questions: (1) What are the EC’s intended objectives that led to the issuing of the Statutory Audit Reform?; (2) What are the measures actually put in place at the EU level in order to reach these intended objectives? and (3) How these measures have been implemented within the Italian context and what are the main change that the new regulatory framework produced/is supposed to produce?The reminder of the paper is structured as follow. In the next section, a brief discussion of the research methodology applied in this paper will take place, while in section three, the course of the audit reform in the European context will be presented following a program theory model. In the fourth paragraph, the audit reform will be analysed with reference to the Italian context and, finally, some insights and conclusion will be discussed about the current and potential impact of the new legal framework on the audit profession.

2. Design of the Study

- Rose and Miller [39] define government as a problematizing activity, because it poses the obligations of rulers in terms of the problem they seek to address. According to the authors, indeed, the history of government is a history of problematizations in which politicians and other powerful subjects have measured the real against the ideal [39]. Political discourse, in fact, is the domain for the formulation and justification of idealised schemata for representing, analysing and reflecting reality [39]. In their conception of government, therefore, programmes are not simply formulations of wishes or ideals, but rather they lay claims to a certain knowledge of the problem to be addressed. Governing a problem thus requires that it can be represented in such a way that it can enter in the sphere of conscious political calculation. This means that programmes presuppose that the real is programmable, that it is a domain of certain determinants, rules, norms and processes that can be acted upon and improved by authorities [39]. The authors, moreover, state that government is also a domain of strategies, techniques and procedures through which authorities seek to render programmes operable, and by means of which a multitude of connections is established between the aspirations of the authorities themselves and the activities of groups and/or individuals.Program theory is defined as “the mechanisms that mediate between the delivery (and the receipt) of the program and the emergence of the outcome of interest” [46] as it analyses “the conditions of program implementation and the mechanisms that mediate between processes and outcomes as means to understand when and how a program works” [45]. According to Rogers et al. [37], moreover, a program-theory driven evaluation is premised, both conceptually and operationally, on an explicit theory or model on how a program causes certain intended outcomes as well as on an evaluation that the observed outcomes are, at least partly, reached because of this model.Program theories are usually represented as graphical diagrams or by means of narratives that specify the relationships among programmatic actions, outcomes and other factors. Figure 1 exposes an example of the graphic representation of a program theory.

| Figure 1. Linear program theory model. Source Coryn et al. (2011, p. 201) |

|

3. The Statutory Audit Reform in Europe under a Program Theory Perspective: Inputs, Activities and Outputs

- The contemporary development of international audit regulation is connected to the growing significance of international investors who demand financial reports that are prepared and audited in accordance with globally accepted international standards [28]. The basic role envisaged for the auditors in the European Union context is to protect the public interest, by giving assurance that financial reports disclosed by companies are reliable and comparable in order to guarantee the proper functioning of the internal market [34, 13].Over time, however, the role of statutory auditors has often been questioned because of the important financial failures that have occurred in many countries [43, 36, 31, 6]. Consequently, auditing firms, professional and regulatory bodies have often been subject to criticisms and have faced pressures to restore public confidence in auditing [27], with specific reference to the function of statutory auditing and auditors’ independence [13].

3.1. The European Commission Policy about Statutory Audit: from the 1996 Green Paper to the Directive 2006/43/EC

- Around the late 90s, the EC found it difficult to respond properly to these questions because of the lack of a complete regulatory framework surrounding the statutory auditing at EU level. The Commission itself, in 1996, has recognized the absence of a common view at EU level on the role, the position and liability of the statutory auditor and thus has published a Green Paper intended to shed light on the abovementioned issues in order to take further EU level actions in this area [13]. One of the main concerns expressed by the Commission was the risk that the financial statements of European companies were not be accepted within international capital markets unless they have been audited by an independent and qualified professional in accordance with auditing standards accepted worldwide [14]. The policy conclusions stemming from the Green Paper included the setting up of a Committee on auditing, whose key responsibilities may be summed up as follows: the examination of the external quality assurance and monitoring systems within the Member States; the revision of the existing auditing standards, in order to assess the extent to which they provide adequate guidance to European auditors in coping with the issues raised by the significant development in accounting standard setting; and the development of principles on auditors’ independence.Corporate scandals in the early 2000s led the Commission to issue a formal regulatory response to the crisis of trust in auditors’ independence, competence and general levels of ethical commitment. In 2002 was thus enacted the “Recommendation on Statutory Auditors: Independence in the EU”. Meanwhile, the Commission continued its work on the possible acceptance of ISAs as the European standards of auditing. Following the measures enacted by the United States in the aftermath of Enron financial scandals (i.e. the enactment of Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002 and the establishment of Public Company Accounting Oversight Board), the EU recognized the need to provide new regulation for statutory auditing [30].The new Statutory Audit Directive was eventually issued in 2006 and it replaced the so-called Eighth Directive of 1984 intending to provide a juridical basis for all statutory audits at the EU level. The Commission, indeed, has recognized that further initiatives to reinforce investor confidence in capital markets and to enhance public trust in the audit function in the EU were required in the aftermath of corporate financial collapses (within and outside the EU), but it was also aware of the risk of “legislating by accident” [30].On this basis, the Directive aimed to improve and harmonise the quality of audits by enacting measures related to three main issues: the potential acceptance of ISAs as EU standards for audit; public oversight on audit quality and measures related to competences and independence of auditors. Another relevant issue addressed by means of the 2006 Directive was the provision of a specific discipline for the so-called Public Interest Entities (PIEs), i.e. listed companies, credit institutions and insurance undertakings.It must be noticed that although this regulatory provision has tried to improve the minimum level of harmonization of Member states’ regulatory audit frameworks, several issues have remained unaddressed. One of the most relevant items that has remained unresolved has been the acceptance (and under what conditions) of ISAs as the reference standards for audit in the EU. Even though the Commission has recognized that the adoption of these high-quality standards would have determined a relevant improvement of the statutory auditing at the EU level (with specific reference to the mutual international recognition of the statutory audits), it was also concerns over the endorsement of standards developed by the IAASB, a private sector standard-setter body [30]. In this respect, the Commission has funded a research project concerning the use of ISAs that has revealed strong support for such an endorsement [11].

3.2. The Impact of Global Financial Crisis on Audit Regulation: Towards the Directive 2014/56/EU and the Regulation n. 537/2014

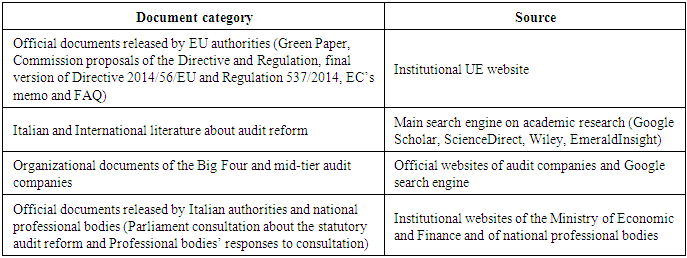

- When the global financial crisis occurred, since 2007, significant questions arose about the effectiveness of financial reporting and auditing [27, 43]. Several scholars, however, referred to a “good crisis” for the auditors [29, 2]. In contrast with corporate collapses occurred in 2000s, in fact, the role of auditors in the credit crunch appear to have received less coverage by media [47, 43]. In this respect Michael Barnier, the European Commissioner for Internal Market and Services, claimed that, in the immediate aftermath of the crisis, while the role of the main economic and financial actors (such as banks, hedge funds, credit rating agencies etc.) were immediately called into question, the role of the auditors has not been really questioned. The EC, indeed, have focused its attention on the urgent measures necessary to stabilize the market and on the role of major economic and financial actors in causing it.Humphrey et al. [29], however, underlined that the apparent lack of visible questioning of the audit function in the midst of the crisis did not mean inactivity, nor an intent to preserve the status quo. Rather, the auditing profession proactively reacted to the financial crisis, using various communication modes and interactions with regulators and governmental bodies to clarify the specific role and obligations of the auditing function [47].There was, however, the need to improve regulatory practice. As Mario Draghi (the Chairman of the Financial Stability Forum since 2006) underlined, the weaknesses showed by the global economy during the financial crisis came from “gaps and inconsistencies in regulatory regimes”, thus highlighting the need to “review and extend the regulatory perimeter to ensure that all financial activities are subject to adequate transparency standards and safeguards where they pose material risk” [12].The EC, therefore, announced that a Green Paper would have been published in order to shed light on the role and governance of auditors. In 2010 was therefore issued a Green Paper entitled “Audit Policy: Lessons from the Crisis” that was intended to stimulate a debate on what needs to be done to ensure that both audits of financial statements and auditor reports are “fit for purpose” [18]. The major standpoints on which the Green Paper was based might be summed up on four interconnected elements: the audit market; the communication between auditors and stakeholders; the governance of audit firms and the public oversight on auditors.With reference to the audit market, the Commission has expressed concerns about its competitiveness and robustness, highlighting the excessive concentration of the market and the systemic risk associated to the potential failure of one of the Big Four, as well as the negative consequences that such a concentration has for clients’ choice. In this respect, the Green Paper included several proposals related to compulsory joint audit, mandatory rotation of the audit firms and the development of a contingency plan in the event of the demise of a systemic audit firm, which allows avoiding disruption in the provision of audit services and preventing further structural accumulation of risk in the market [18].Regarding the communication flows between auditors and stakeholders, the Commission have expressed the desire of “going back to basics”, placing less reliance on compliance and system work and focusing more on substantive verification of the balance sheet. Moreover, it has been underlined the critical issue of the exercise of professional scepticism with regard to key disclosures in financial statements. Furthermore, the EC has proposed various measures intended to improve the audit report, such as the possibility of greater disclosure of the financial statement components verified by auditors (even distinguishing between those directly verified and those verified on the basis of professional judgement) and the use of predictive information in order to provide a better going concern opinion [18].The main aim of the Green Paper about the governance and independence of audit firms was to improve auditors’ independence and their ability to manage conflicts of interest. One of the most relevant proposals on this topic refers to the feasibility of a scenario where the audit would become a statutory inspection wherein the appointment, remuneration and duration of the engagement would be determined by a third party, perhaps a regulator, rather than by the audited companies. Other proposals about the strengthening of auditors’ independence refer to mandatory rotation of the audit firms (not only of the audit partner, as already required by the Directive 2006/43/EC), a further development of the norm about the provision of non-audit services (hereinafter NAS), audit fees’ structure and proportion and organizational requirements of the audit firms [18].Finally, due to the central role played by the supervision of audit firms, the Commission underlined that there was the need to a more integrated oversight system at EU level. One of the options proposed in this respect was the opportunity to transform the European Group of Auditors’ Oversight Bodies (EGAOB) into a committee, which could reinforce co-operation between national oversight authorities as well as ensure a common approach to the inspection of audit firms. Alternatively, the EC proposed the establishment of a new European Supervisory Authority.Humphrey et al. [30] offer a critical discussion of the Green Paper and highlight that, while proposals about the improvement of audit market and audit regulation (such as the proposal to enact more restrictive norms in enforcing auditors’ independence) have been clearly identified within the document and have received explicit attention, the issues related to professional practice and auditor judgement have been less visibly addressed. Specifically, according to the authors, the Commission did not talk about the extent to which the boundaries of the audit profession have changed, are changing or they need to change in order to perform its central role in contributing to financial stability or being “fit for purpose”. Furthermore, the Green Paper failed to consider in any substantial depth the key drivers of change in audit practice. The commission, indeed, revealed a number of concerns about professional judgement process talking about the need to “going back to basics” focusing more on substantive verification of the financial statement, or by reinforcing the exercise of professional scepticism, or by improving the informative capability of the audit report. There has been, however, no discussion as to why this need to going back to basics has emerged.In order to give answer to the first question of this paper, Table 2 summarizes the objectives posed with the Green Paper and the related proposed measures.

|

3.3. The New Audit Regulatory Framework in Europe: the Directive 2014/56/EU and the Regulation n. 537/2014

- The publication of the Green Paper has initiated a long-lasting consultation process (the EC has received almost 700 responses from different categories of stakeholders) at the end of which, in 2011, the Commission has released two different regulatory proposals: a proposal of Directive, intended to regulate the overall statutory audits within the EU, and a proposal of Regulation, with the aim to provide specific regulation for the statutory audits of PIEs. After an extensive debate, in 2014, a new legislative package has been eventually enacted by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU, consisting in the Directive 2014/56/EU and the Regulation n. 537/2014. Under a program theory perspective, the program (output) has been eventually delivered.Program impact theory, indeed, aims to describe the cause and effect sequence in which certain program activities are the instigating causes and certain social benefits are the effect they eventually produce [40]. In this respect, the measures introduced by means of the new legislative package will be analysed in order to investigate their linkages and their consistency with the EU’s intended outcomes.

3.3.1. Improve Communication between Auditors and Stakeholders

- Among the measures proposed in order to improve the communication between the auditors and the stakeholders (both internal as the Audit committee, and external, as the users of financial statements), it has to be made a distinguish between those measures actually implemented (at least partially) within the new regulatory framework and those which have been dismissed in the legislative process.With reference to the latter, neither the need to “go back to basics” and rely more on substantive verification of the balance sheet items, nor the opportunity to consider not only historical, but also forward-looking information in issuing the audit opinion have been taken into account during the development of the regulatory intervention. The vast majority of professionals who responded to the consultation process initiated after the release of the Green Paper, indeed, has underlined that a stronger focus on substantive audit procedures and less reliance on compliance and system work would not automatically result in a higher assurance on the proper valuation of the balance sheet’ components. Furthermore, respondents among business representatives have stated that a more substantive audit approach would be feasible only in relation to the audit of small entities, wherein a risk-based approach does not make sense. In contrast, when the audited entity is a medium-sized or large company, an audit approach based on the risks of material misstatements in the balance sheets is more efficient.Regarding the opportunity for auditors to assess also forward-looking information and thus provide an economic and financial outlook of the company [18], all the respondents to the consultation have expressed a negative opinion, claiming that auditors are not and should not become credit rating agencies.The measures related to the exercise of professional scepticism and the adoption of clarified ISAs, included the principle on quality controls (ISQC1), as the reference standards for statutory audits within the EU, instead, have been adopted in the audit reform (Article 21 and Article 26 of the Directive 2014/56/EU, respectively) without any substantial change during the regulatory process. These measures are intended to ensure a substantive harmonization and a high quality level of the statutory auditing among Member States. Nevertheless, respondents to the consultation process have expressed different opinions about the opportunity to adopt a binding or a more flexible approach on the adoption of these international standards. Representatives of the profession (professional bodies, the Big Four and small and medium practitioners) have expressed a broad support for a binding adoption of clarified ISAs, while representatives of the investors as well as public authorities, have shown a propensity to a more flexible approach to the adoption of ISAs, e.g. by means of a recommendation. In their opinion, indeed, such an approach could facilitate forms of review of the standards so as the Commission and other relevant stakeholders could assess whether they are “fit for purpose”. Moreover, this approach would enable a high-quality audit, since the auditors would be more focused on the overall purpose of the audit function, rather than on performing an audit focused on standards compliance. Finally, representatives from business contexts have expressed less enthusiasm for the adoption of clarified ISAs. The reasons of their reservations are threefold: the un-balanced composition of the IAASB in favor of accountants, which might impair the due process of standards' development; the risk that a binding approach to the adoption of clarified ISAs will result in an even more compliance-oriented audit and, finally, the cost dimension associated to the adoption of these standards.Regarding the measures intended to improve communications between auditors and stakeholders, the Commission, although with some changes compared with the initial proposals included in the Green Paper, has revised the content of both the audit report and of the report to the supervisory board. With reference to the audit report, the Regulation imposes to PIEs’ auditors to include information about the most significant addressed risks of material misstatements, a summary of the auditor’s response to these risk and other information about auditors’ independence and about the provision of NAS (article 10, Regulation n. 537/2014). In this respect, the Commission has not accepted the suggestions emerged during the consultation process, neither its own initial proposals (see Table 2). Almost all stakeholders, indeed, have highlighted the need to improve the audit report with more qualitative information about audit methodologies and key judgements.With reference to the report addressed to the audit committee, instead, Regulation 537/2014 imposes that auditors should provide information about their independence, the audit methodology followed during the engagement (including which categories of the balance sheet have been directly verified and which ones have been verified through system and compliance testing), and materiality thresholds.

3.3.2. Reinforce Governance and Independence of the Auditors

- In order to achieve the second main intended objective of the statutory audit reform, the Green Paper proposes several measures referred to the internal organization of statutory auditors and audit firms. Governance’s structure, indeed, should help auditors to prevent threats to their independence [25]. In this respect, the Commission has stated that the owners, shareholders and managers of an audit firm should not intervene in the statutory audit engagements in any way which jeopardizes the independence and objectivity of the statutory auditor who carries out an audit engagement. Moreover, compliance with statutory audit obligations should be ensured by means of appropriate internal policies and procedures also in relation to the employees and other people involved in the statutory audit activity. The aim of those internal policies should be that of preventing and addressing threats to auditor’s independence as well as to ensure quality, integrity and thoroughness of the statutory audit [26], consistently with the provisions of the international standard on quality controls (ISCQ1).One of the most relevant measures introduced with the statutory audit reform is referred to the mandatory audit firm rotation, although this provision has been considerably lightened during the regulatory process. The proposal of Regulation, indeed, suggested mandatory rotation after six years, which could be extended to nine years in case of joint audit, and a cooling off period of four years to the statutory auditor or to the audit firm or to any members of its network within the Union after the expiring of the maximum duration of the engagement. The maximum duration of the engagement actually imposed by the Regulation, instead, is of ten years, which may be extended by Member States to twenty years, when a public tendering process for the statutory audit is conducted, and to 24 years, when joint audits are conducted, requiring in all cases a cooling off period of four years (Article 17, Regulation 537/2014). Consequently, the maximum rotation period has been extended drastically comparing the 2011 proposal to the final audit regulation which implies that rotation takes place less often under the final version than rotations under the proposal.Another relevant measure introduced in order to preserve auditors’ independence is referred to the prohibition of providing NAS to the audit clients, as well as to the limitation to the audit fees' structure. Regarding the former, The Green Paper as well as the 2011 proposal Regulation suggested the establishment of pure audit firms, which result in “a complete ban on the provision of NAS by the large audit firms” [24]. Only several related financial audit services might be allowed under the proposal regulation 2011. According to the Commission, indeed, the provision of services other than statutory audit to the audited entities by the statutory auditors, audit firms or members of their networks may compromise their independence. Moreover, the provision of NAS by an audit firm to an audited entity would prevent to that audit firm from carrying out statutory audit of that company, thus resulting in a reduction of the audit firms available to provide statutory audit services, especially with regard to the audit of large public-interest entities where the market is already highly concentrated [18]. The consultation process initiated after the release of the Green Paper has shown different opinions expressed by the various stakeholders involved. Both representatives from professional association and the Big Four have generally opposed to the prohibition of NAS, because any such provision would have weakened the general economic independence of audit firms and the range of skills they can offer. A more favorable opinion with this measure was expressed by representatives of investors ad mid-tier audit firms. The former, indeed have identified the provision of NAS as the main source of conflicts of interest and of an unwarranted competitive advantage for the audit firm. The latter, instead, were generally agree with this provision when referred to the PIEs, but have appealed for “safe harbors” regarding the prohibition of NAS for smaller clients, considering that performing such services represents a necessary condition for their very existence. Furthermore, although public authorities disagreed with this prohibition due to the possible loss of knowledge spillovers arising from the provision of NAS, which increase audit quality, academic respondents have underlined that the knowledge spillovers are generally used in reducing audit costs rather than in enhancing audit quality. More, a ban on the provision of NAS by audit firms would have no doubt positive effects on third parties’ perception about auditors’ independence. Nonetheless, at the end of the regulatory process, not only there has been no complete ban preventing auditors from offering NAS to their audit clients, but the black list of prohibited NAS has also been significantly reduced compared to the 2011 proposal.The new audit reform also has introduced fee limits for audit services which were already suggested by the Green Paper. However, since the proposal Regulation required pure audit firms, the requirements for fee limits on NAS, related financial audit services and total fees significantly differ from the requirements of the 2014 Regulation. Whereas the proposal, indeed, has suggested that the “fees for the provision of related financial audit services to the audited entity should have been limited to 10% of the audit fees paid by that entity” [24], the 2014 Regulation has allowed that the not prohibited NAS can amount to “70% of the average of the fees paid in the last three consecutive financial years for the statutory audit(s)” (article 4, Regulation 537/2014). Consequently, the fee limit for allowed NAS has been extended.In addition, the new audit reform regulates the total fees received from one audit client. The EC Regulation proposal required that the auditor should inform the audit committee if the total fees “received by an auditor from a PIE reaches more than 20% or, for two consecutive years, more than 15% of the total annual fees” [24]. In addition, if the percentage of total annual fees from one PIE reaches more than 15% for two consecutive years the competent authorities have to be informed and then they have to “decide if the audit can be continued for not more than 2 years” [24]. The final Regulation has followed the stricter limit of 15% of total fees received by an auditor from a PIE but, instead of calculating them on the basis of two consecutive years as the Regulation proposal, the 2014 Regulation has allowed the 15% for three consecutive years. In addition, the audit committee has to be informed if this 15% is exceeded but there is no obligation to inform competent authorities. Consequently, also the requirements on the total fee limit have been weakened throughout the development of this measure.Finally, among the measures proposed in order to reinforce governance and independence of the auditors and audit firms, the Commission has considered the feasibility of a scenario where the audit role would become one of statutory inspection wherein the appointment, remuneration and duration of the engagement would be the responsibility of a third party, perhaps a regulator, rather than of the audited company itself [18]. There has been no further development of this measure, which has been rejected in the final version of the audit reform, perhaps also in light of the comments emerged from the consultation process. Respondents from all categories of stakeholders, indeed, on the one hand, have recognized the presence of an inherent conflict of interest arising from the fact that auditors are appointed and remunerated by the same audited entities. On the other, however, they believed that in such a scenario the accountability of auditors and their relationship with stakeholders would be seriously undermined. In order to address this conflict of interests, therefore, some respondents have proposed a strengthening of the audit committee or a third party involvement in very exceptional cases, such as those of systematically important entities.

3.3.3. Reduce Concentration the Audit Market

- With reference to the audit market, the Commission has expressed concerns about its competitiveness and robustness, highlighting the excessive concentration of the market. According to the Commission, indeed, the markets for audits of listed companies is, in the main, covered by the so called Big Four, whose total market share in terms of revenues exceeds 90% in the vast majority of EU Member States [18]. Such a concentration has, on the one hand, negative consequences for clients’ choice and, on the other, it might cause a systemic risk associated to the potential failure of one of the Big Four. In this respect, the Green Paper included several proposals related to compulsory joint audit, mandatory rotation of the audit firms, the prohibition of “Big Four” contractual clauses and the development of a contingency plan in the event of the demise of a systemic audit firm [18].Among these measures, only the prohibition of “Big Four clauses” has been fully adopted, without changes compared with the initial proposal. The appointment of more than one auditor represents only an opportunity, and there is no compulsory norm that imposes joint audit, either for PIEs. As discussed in the previous paragraph referred to governance and auditors’ independence, also the provision of mandatory audit firm rotation has been modified during the regulatory process.Finally, there has been no further development about the proposal referred to a contingency plan, which may allow for a rapid resolution in the event of the demise of a systemic audit firm.

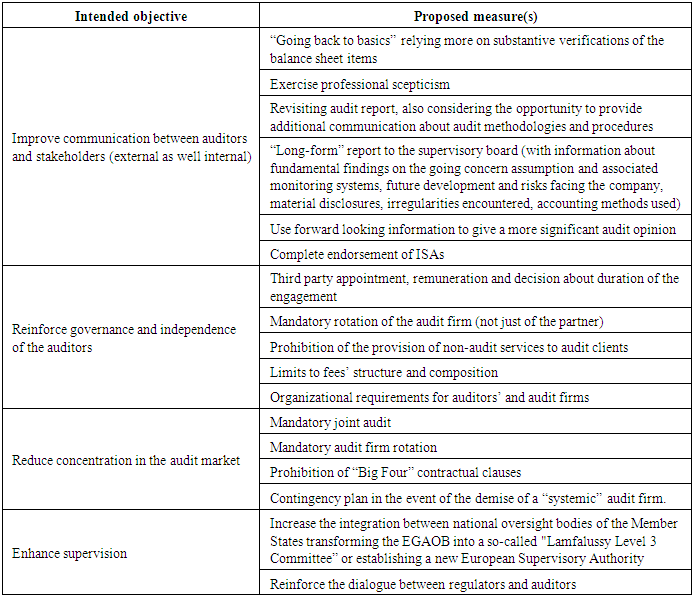

3.3.4. Supervision

- The amended Directive and Regulation require a restructuring of public oversight of auditors. Nevertheless, the measures intended to enhance oversight at national and European level have also undergone some changes. On the EU-level, the coordination between the Member States’ authorities is not designated to the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) as suggested by the 2011 proposal regulation and proposal directive [23, 24]. Instead, cooperation will be organized by the Committee of European Auditing Oversight Bodies (CEAOB) “which should be composed of high- level representatives of the competent authorities” [25, 26]. However, ESMA is in charge of “the cooperation between Member States and third countries in the field of public oversight of PIEs” [26]. Consequently, the CEAOB with the support of ESMA, “take(s) over the tasks of the existing European Group of Auditor Oversight Bodies (EGAOB)” [26].On the national level, the audit reform further requires that “each Member State should designate a single competent authority to bear ultimate responsibility for the audit public oversight system” [26]. Moreover, in order to increase the power of these authorities, the sanction regime has been strengthened compared to the Directive 2006/43/EC. However, the stricter sanctions which are granted to the national oversight bodies are not mentioned in the Regulation as suggested by the 2011 proposal but instead in the 2014 directive [24, 25]. This implies that the sanctions conferred to the oversight bodies do not only apply to PIEs [26].All in all, the schemata proposed in Table 2 may be reconfigured as represented in Table 3.

|

4. Evaluating the Impact of the Statutory Audit Reform: the Italian Case

- The Italian environment represents a suitable context in which analyse the adoption of the EU Statutory Audit Reform for several reasons. First, the Italian audit environment has some distinctive characteristics that make it an appropriate research site with respect to some of the most relevant measures introduced by the EU reform.Statutory audit in Italy has been regulated for the first time in 1975, with the Presidential Decree no. 136, which has introduced the mandatory certification of listed companies’ financial statements. The statutory audit legal framework has then remained substantially the same until the 90s, when the national regulator has adopted the European Directives about annual accounts (Fourth Directive), consolidated accounts (Seventh Directive) and about qualifications of persons responsible for carrying out the statutory audits of accounting documents (Eighth Directive). Nonetheless, the Italian regulatory system on statutory audit had still several anomalies without any correspondence when compared to those in force in the other Member States. One of the most relevant features of the Italian audit environment, indeed, is the simultaneous presence of two different statutory audit regimes: the one referred to listed companies and the other referred to the unlisted ones.The adoption of Directive 2006/43/EC, by means of the Legislative Decree 39/2010, has represented the opportunity to reach a substantive harmonization between national and EU statutory audit's discipline. Nevertheless, several relevant issues have remained unresolved after the adoption of the Legislative Decree no. 39/2010, mainly due to the fact that the Italian legislator has charged the Ministry of Economic and Finance and the Italian Stock Exchange Supervisory Commission (the Consob) with the issuing of numerous detailed decrees that were necessary to reach a complete and effective adoption of the EU norms (such as the enabling process for statutory auditors, the performing of quality controls by the oversight bodies, independence issues related to statutory audit of PIEs etc.).Finally, with the adoption, on July 2016, of the legislative package issued by the EU in 2014 (Directive 2014/56/EU and Regulation n. 537/2014), the national audit regulatory framework has been “reinforced, with reference to harmonization of the discipline, auditors’ independence and ethic principles, auditing standard and efficient and effective functioning of the sanctioning measures” (Italian Parliament, 2016).

4.1. Measures Introduced within the Statutory Audit Reform and Intended Outcomes

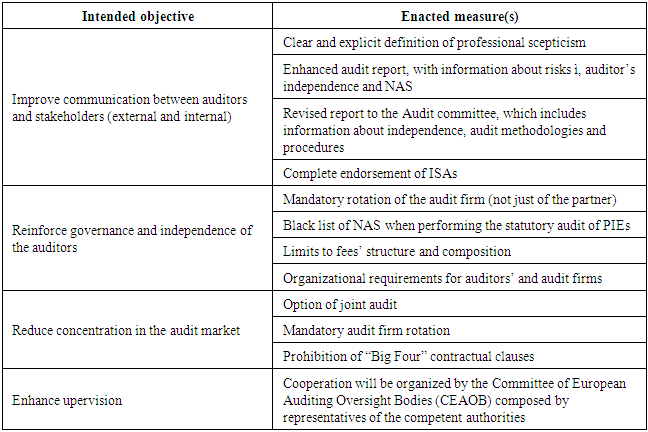

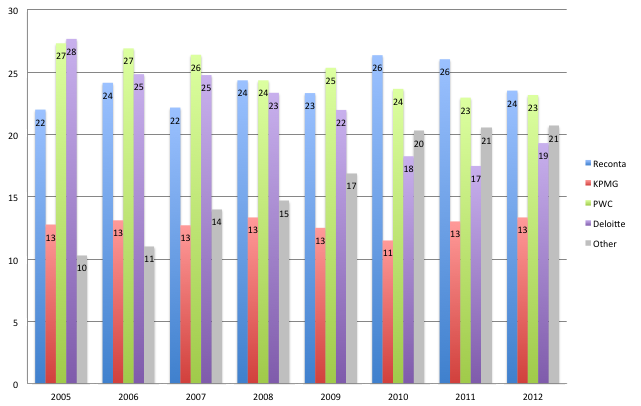

- The underlying objectives, which have informed the issuing of the Statutory Audit Reform at the EU level, impact differently on the Italian context depending on the fact that we consider the statutory audit of the PIEs or the statutory audit of other entities.With reference to the former (PIEs), indeed, the national regulatory framework on statutory audit provided already a considerably more rigorous and severe regime, compared to that previously in force at the EU level. In this respect, in fact, the Italian regulation imposed mandatory audit firm rotation since the first introduction of a statutory audit regulation in 1975. The original version of regulation allowed an auditor term to be renewed every three years up to a maximum tenure of nine years. Italian listed companies, therefore, were subject to both a retention and a rotation rule. That is, once appointed, the audit firm was retained for at least three years and, at the end of each three-year period, the auditee had the option to re-appoint the auditor for an additional term. At the end of nine consecutive years of engagement, a change of the audit firm was mandatory. This retention rule was then dropped in 2006 and, once appointed, the auditor is thus retained for the maximum engagement period, i.e. nine years. [5]. Moreover, Italian law requires the rotation of the audit partner or of the individual auditor after a maximum retention period of seven years.It is worth of notice, however, that the presence of a mandatory rotation provision within the Italian legal framework has not brought any benefit as far as independence or market openness [7]. Market concentration in Italy, at least referred to the statutory audit of PIEs, is one of the highest in the entire EU (see Figure 2), as the Big Four cover more than 80% of the statutory audit engagements of listed companies.

| Figure 2. Distribution of statutory audit engagements in Italian listed companies (source: online) |

5. Concluding Remarks

- The recent intervention of the EC in the auditing field with the enactment of a new regulatory package according to which statutory audits must be performed within the EU may be interpreted as the output of a process of “government problematization”, as defined by Rose and Miller [39]. According to Power [35], changes in regulatory structures may be motivated by legitimacy-seeking behaviour. The recent changes of regulatory structure for statutory audit may reflect the effect of external pressures from global capital markets towards increasingly standardized and high-quality regulatory practice for audit on a global basis. In this respect, the weaknesses showed by the global economy during the financial crisis came from “gaps and inconsistencies in regulatory regimes”, thus highlighting the need to “review and extend the regulatory perimeter” [12].As stated by Power [35] when addressing the misguided focus by regulators on the audit process, indeed, “auditing practice can be regarded as a self-regulating system whose components are an interacting, semi-institutionalized and loosely coupled whole and the legitimacy of audit is constantly threatened by the misalignment of expectations about and within the system. These threats lead to pressures for the rationalization, formalization and transparency of the audit process”.The study provides evidence in which way the measures of the audit reform and the EC’s intended objectives have been translated and applied in the Italian audit environment. The proposed analysis revealed that the EC’s measures intended to lead to the desired outcomes has been subject to more or less substantive changes within the regulatory process. Moreover, the Italian experience seems to suggest that some the measures enacted in order to reach an overall enhancement of audit quality and auditor independence, as well as a more dynamicity in the audit market, such as mandatory audit firm rotation and prohibition of NAS, do not have a direct and positive effect on real auditors’ independence nor on market openness [5, 7]. It seems possible to quote what Humphrey et al. [30] point out about regulatory intervention. The authors, indeed, highlight that reforms that are not well informed by and well grounded in the domain of professional practice and the wide array of factors influencing and shaping processes of professional judgment run the risk of producing unintended and potentially dysfunctional consequences.According to Carnegie and O’Connell [8], promptly instigated governance reforms may also be adopted without a full and adequate consideration of their intended or unintended effects. In the event of a crisis, ‘‘regulatory priorities are driven by issues coming to the public’s attention rather than by rational appraisals of risks’’ [3]. As concluded by Romano [38] in a long critique of the US Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, where a regulatory intervention is conceived in an environment of hostile public reaction to corporate financial scandals, it results in a lack of proper due process, including inadequate research, and full consideration of the likely impact of the legislation on companies and other relevant stakeholders.In order to properly assess if this might be the case, however, further research is needed when the Statutory audit reform will become completely effective in all the Member States.The study has some relevant limitations. The Italian setting, indeed, is characterized by similarities as well as peculiarities compared with the other Member States, which may limit the transferability of the study to other EU countries. Nevertheless, the limitation of a single case study also presents an area of possible future research by applying the concept of this study to other EU Member States. This would reveal major differences in the logic of the audit reform occurring through special customs and regulations in the area of auditing in different Member States.This research has bot theoretical and practical implication. From a theoretical strand, indeed, this study applies the program theory to a new research area. Prior studies have applied this theory mainly in the field of social benefit programs, especially healthcare [40]. Consequently, a research gap persists as the program impact theory has not been applied to regulation in the field of auditing. Hence, this paper contributes by indicating a new approach to analyse audit regulation. It is, therefore, possible to add knowledge to the discussion about the connectivity between the audit reform’s measures and objectives by assessing these assumed connections by means of program impact theory. Simultaneously, this study contributes to the program theory by extending its application. Also, since the paper demonstrates practical interrelations between the objectives and the measures of the audit reform, it contributes to the understanding of regulation in the area of auditing. Due to the objective focus of this study, the analysis is relevant because it enables a neutral perspective to a subjectively guided discussion about the audit reform.This study has also practical relevance, since it aims to provide knowledge about the audit reform. Furthermore, this analysis is significant as it points out interrelationships between the enforced measures and the intended objectives, which then lays the groundwork for future research in this area. Moreover, as the study is conducted half a year after the implementation of the audit reform for Member States, the analysis is done within the interesting context of elaborated discussions amongst academics, professionals and regulators. Hence, the characteristic of being a recent topic further makes the study relevant for society, the audit profession, as well as the regulators.

Note

- 1. From the interview to Commissioner Barnier, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/archives/commission_2010-2014/barnier/headlines/news/2010/04/20100427_en.html.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML