-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2016; 5(5): 228-232

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20160505.02

Impact of M&A Announcement on Acquiring and Target Firm’s Stock Price: An Event Analysis Approach

1Faculty of Business Studies, BGMEA University of Fashion and Technology, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Bangor Business School, Bangor University, Bangor, United Kingdom

Correspondence to: ATM Adnan, Faculty of Business Studies, BGMEA University of Fashion and Technology, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This research paper empirically analysis the differences in stock price reaction due to merger announcement both target and acquiring companies. Moreover, before merger announcement the role of insider information is also empirically tested and explained. However, the traditional event study methodology is used to conduct the research and investigation. To find out the period where the price run-up initiate, how the stock market reaction after the merger and finding the target and the merger companies cumulative average abnormal return (CAAR), therefore event window has been considered and compared. The findings indicate pre-announcement period price run-up for the both target and acquirer companies which indicate the leakage of information or an anticipation of some good news. On the other hand, post-announcement period price downgraded for the acquirer companies. Noticeably, the trend pattern is not consistent for the both target and acquirer companies over the 10 days period.

Keywords: Stock, Acquisition, Merger, Event study, CAAR

Cite this paper: ATM Adnan, Alamgir Hossain, Impact of M&A Announcement on Acquiring and Target Firm’s Stock Price: An Event Analysis Approach, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 5 No. 5, 2016, pp. 228-232. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20160505.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In finance, mergers are one of the most researched areas, yet there are some basic issues still remain unsolved. Most of the empirical research on mergers generally emphasizes on daily stock returns nearby announcement dates and after mergers, only few studies look at the long-run performance of acquiring firms. However, some papers concluded that over one to three years period after the mergers these firms understand significant negative abnormal returns (see Asquith, 1983; Magenheim & Mueller, 1988). Generally, to test a signaling model researchers use traditional event-study residual analysis. In the event study residual analysis is used as a main indicator of how the market reacts to a signal, after merger announcement. Residual analysis have reported a positive, monotonic market reaction to a signal when use event studies. In this case, abnormal stock returns are normally used.In this study, a merger or an acquisition announcement is considered as an event. The objectives of this paper are: (a) investigating the effect of merger announcement for the both acquirer and target company’s stock price, (b) using the event studies examine whether publicly available information or insider information drives the observed price pattern of the target and acquirer companies, and (c) studying the comparison of stock prices before the announcement of merger and post announcement stock prices patter. Finally, by the examining the daily stock closing price of the entire stocks pre-merger and post-merger announcement, study the merged company’s stock price post-merger & acquisition.

2. Literature Review

- Merger and Acquisions have become very popular for the corporate growth strategy over the last few decades whether mergers increase the shareholder value for the company that undertaken them. Moreover, shareholders and companies can be benefitted by the mergers, where it increases market share and market power, provides economics of scale and scope, lowers cost of capital, and alleviates redundant corporate costs, others prospective assistances (Ross, Westerfield, and Jordan 2009; Ma, Q., Zhang, W. & Chowdhury, N. 2011). On the contrary, Mergers have some disadvantages as well such as it can hamper shareholder value, operating bigger businesses can be problematic, between acquirers and targets synergy might be overestimated by the managers, as a result they need to pay extra for the targets firm (Roll, 1986). Basically, in the field of M & A to evaluate the performance, there are five approaches commonly used: (1) Event studies (stock-market-based measures), which is used for both in the short run and long run (Haleblian and Finkelstein,1999; Sudarsanam and Mahate, 2006); (2) accounting-based measures (Zollo and Singh 2004); (3) expert informants’ assessment (Hayward, 2002); (4) managers’ subjective assessments (Brock, 2005; Homburg and Bucerius, 2006); and (5) divesture (Mitchell and Lehn, 1990). On the other hand, to measure the performance of M & A, empirical researcher uses two studies mainly: one is accounting studies and another one is event studies. The post-operating performance of the M & A is investigated by the accounting studies. The Post-operating performance for the long term period will be compared to the industry, size or performance with the benchmark of a group of non-acquired firms (Barber & Lyon, 1996). This method has several limitations such as measuring problems, because companies have different accounting rules but it provides a direct measure of the economic impact of M&A (McWilliams & Siegel, 1997). Whether since 1970s event study has been broadly applied in the research of M & A (Martynova and Renneboog, 2008). Moreover, event study is designed to evaluate or measure abnormal stock price effect that is associated with an unanticipated event such as M & A and interestingly, on the arrival of new information in the market that reflect quickly on the stock returns. Generally, event window is defined by the researcher to measure the impact over the any event (Wang, D. & Hamid, M. 2012). Event study: o measure the effects of an economic event on the value of firms Economists use event study and they use financial market data for the valuation of a specific event of a firm. However, the effects of an event will be reflected in the security prices and the measurement of an event economic generally made by the using of security prices which is observed over a relatively short time period. On the other hand, noticeably many months or even years observation needed to get the direct productivity. For the research of accounting and finance, event study can be used on the based on firm specific requirements and economy wide events. Mergers and acquisitions, issues of new debt or equity, earnings announcements and among more research we can use event study and they are the good examples of event study. In my research, I will use event study to examine the impact of event on the stock return of a firm and that is translated into the value of the firm (MacKinlay, A.C. 1997; Gopalaswamy, A.K., Acharya, D. & Malik, J. 2008).There are some benefits of event studies and all the advantages and disadvantages of event studies are abridged below as: (1) Short-term event study can screen the influence of outside factors to large extent; (2) Data are easy to get publicly, allowing study on large sample; (3) It is relatively objective public assessment; (4) Abnormal return is calculated, therefore, data is not subject to industry sensitivity, aiding a cross-section of firms to be studied. On the contrast, researcher cannot be ignored its caveats: (1) Getting stock price is relatively easy, its implementation is difficult; (2) The assumptions are challenging to be met; (3) It fails to take into consideration numerous motives aimed at conducting M & A; (4) In case of the possibility for the sampling biasness therefore it cannot be used for the private firms (Wang, D. & Hamid, M., 2012).Merger Event: When merger occurs between two firms, there is a great deal of attention normally happened. Holmstrom and Kaplan (2001) explained on their paper merger waves in the year of 1980s and 1990s, moreover, from the year of 1898 to 1902 merger waves dating back was documented by Nelson (1959). However, the first merger waves occurred from 1897 to 1904 (Kleinert, J., & Klodt, H., 2002). The event study is required for the valuation of merger and acquisitions and the merger effects on the profits and efficiency of a firm or company (Cox and Portes, 1998; Pautler, 2003). The stock returns of the acquiring and acquired firm and stock returns of competitors are the ways for the checking of proposed merger announcement (Gopalaswamy, A.K., Acharya, D. & Malik, J. 2008).Post-merger performance: Most of the empirical research on mergers presented long-run underperformance after mergers and they mainly focus daily stock returns surrounding announcement dates. Many research papers described that after the mergers some firms experience significant negative abnormal returns over the more than one year (Asquith, 1983; Magenheim and Mueller, 1988; and Agrawal and Jaffe, 2000). After a merger over a six year period long significant cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) was between -2.23% and -2.62% (Langetieg, 1978). Similarly, Asquith (1983) reported that after the completion of mergers within one-year acquiring firms’.CAR decreases by 7.2%. Jensen and Ruback (1983) found from their survey for the one-year post merger and they found negative CAR, which is -5.5%. Lahey and Conn (1990) reported for the two benchmarks and they found significant three years CAR, those are -10.2% and – 38.57% respectively. Rau and Vermaelen (1998) reported that they used the size and book to market adjustment method for the finding the CAR, they found -4% CAR for the three years.

3. Materials and Methods

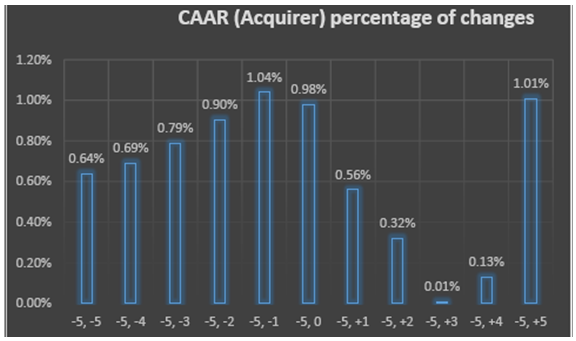

- To study this research, collected samples from Thomson one banker and on the research, there are 50 target firms and 50 acquirer firms. In order to conduct research, both target firms and acquirer.Firms selected from the USA markets for 1st January 2015 to 31st December 2015. All the firms are listed on the New York, American and NASDAQ stock market. The announcement date is specified as day zero in the event time of my study and whether regarding the merger on that day target or acquiring company first publishes disclosed information. However, some public announcements were made after and some were made before, there were some cases in the study. Interestingly, when the merger news published in the media then the market reaction occurred a day before and that could happen in the latter case. Hereafter, in this case, we may inaccurately define the reaction into the market as a day before the news published in the media and we considered it as existence of “abnormal return” which is based on trading on non-public information. This is a bias and in order to alleviate this problem then we defined announcement date as a range covering date and if that day was a trading day then the news published immediate preceding day in the media coverage. In this case, stock price for the day zero i.e. announcement day, is calculated using averages of prices on the day and if it was a trading day on that day immediately preceding that. For each of the stock prices, daily return is calculated using this formula by the excel sheetLog returns (Rj,t)= ln Pt – ln Pt-1= ln (Pt/Pt-1)Where log return indicates the daily return of individual stock return, ln is the log, and Pt represents the closing share price on the day t. There is a benchmark for the calculation of the daily stock return that is -5 to 100. The daily abnormal return and the daily cumulative abnormal return were calculated by the using value of alpha and beta. To understand the extent of pre-announcement, post-announcement and actual merger of companies’ price variations, I made an event window that I already mentioned whether announcement day is 0, five days for the pre-announcement and five days after announcement of merger to understand the stock price reaction. Therefore, abnormal return and cumulative abnormal return are measured based on event window. Abnormal return is the difference between the actual return and the expected return, therefore abnormal return is calculated based on this as followsArj,t= Rj,t- E(Rj,t)Where Arj,t is the abnormal return for stock j on day t and E(Rj,t) is the expected return for the stock j on the day t.The CAR is measured using the following,CARit,;t+K = Σk Ari,,t+kWhere Σk Ari,,t+k is the summation of abnormal return for security j on the day t. The CAARt is calculated using the following,CAARt =ΣCARj,tWhere CAAR refers to the Cumulative average abnormal return and t refers to the event period. In light of the above discussion, to get the impact of stock reaction after merger announcement hypothesis need to be tested that indicates the significance of impact an event. Generally hypothesis testing to be the abnormal returns on the announcement day and around the merger announcement, that is should be equal to or less than 0. The stock prices on average react positively to merger announcement when CAR (after announcement) are statistically significant and are greater than 0. On the contrary, if the CAR is less than zero that indicates the negative significant react on the stock price after the merger announcement. However, traditionally event study is used to specify the performance of stock price over the time period by the analyzing abnormal return for the sample of events are significantly different from 0. Hence, the chances of accurate result still remain uncertain. This assessment are made by the hypothesis testing whether in the event window when there is no abnormal return, it’s called null hypothesis (H0) and Alternative hypothesis (H1) recommends that there is the existence of abnormal return. In this paper, alternative hypothesis (H1) is more appropriate because that represent the significant positive or negative abnormal returns in the event windows. Hypothesis testing has been completed using below mentioned formula to get t statistics.

In this research paper [-5, +5] event window has been considered that refers the time period of 5 days prior to the announcement day of merger and, from the merger announcement day 5 days later time period. Now for the acquirer and target companies pre-announcement and post-announcement event study are analysed and compared. Furthermore, for the complete event window during the period both the acquirer and target company’s returns charts are analyzed by the comparing.

In this research paper [-5, +5] event window has been considered that refers the time period of 5 days prior to the announcement day of merger and, from the merger announcement day 5 days later time period. Now for the acquirer and target companies pre-announcement and post-announcement event study are analysed and compared. Furthermore, for the complete event window during the period both the acquirer and target company’s returns charts are analyzed by the comparing.4. Results and Discussion

- One could expect that the value of CAAR to fluctuate about zero if there were no irregular price movement before to the announcement date. Moreover, If any insider information leakage prior to the announcement date this could be reflected in the daily stock prices and which would show up in the form of positive or negative daily average abnormal returns whether ‘t’ methods zero and a consistent build up in CAAR.

4.1. Event window [-5, +5]

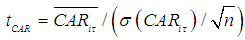

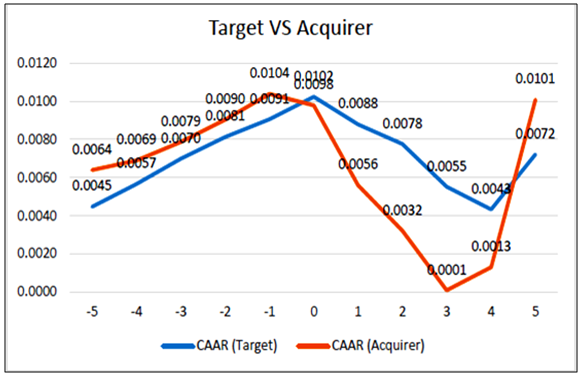

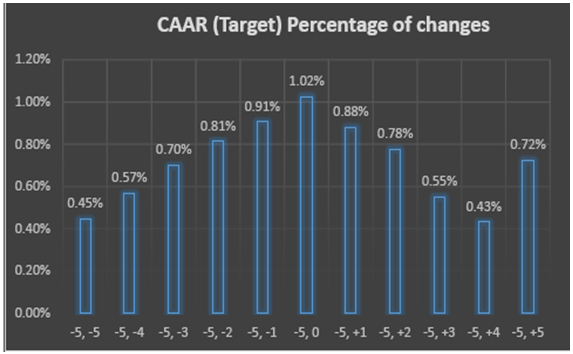

- In the appendix, table 1 presents the value of t -statistics and CAAR for both the acquirer and the target companies in the interval of [-5, +5]. The table shows that the values of CAAR all are positives at the pre - announcement period and post -announcement period. The t -statistics suggests that for the target and acquirer companies there are no 5% significance level. On the announcement day, abnormal returns are positive and no significant impact on the target and acquiring companies. Acquirer companies Abnormal returns for the post announcement period on the day 3rd declined and that is close to 0.

|

| Figure 1. CAAR for the period [-5, +5] |

| Figure 2. Target companies percentage changes of CAAR value |

| Figure 3. Acquirer companies percentage changes of CAAR value |

5. Conclusions

- This study is conducted among 100 listed companies on the US stock markets to document the market behavior around the merger announcement date for the period of 1st January 2015 to 31st December 2015. When the price run-ups start and when the price falls reduce, to know this an event study is conducted using [-5, +5] event window. After conducting this research, it is found that prior to the announcement of merger both the target and acquiring companies CAAR value show an upward trend and this is may be for the reason that leakage of information or the anticipation of merger. Though the CAAR almost equally increased prior to the announcement both the target and acquiring companies and on the day 0 it was almost same but post-announcement period day 1 to day 3 that sudden fall down of cumulative average abnormal return (CAAR) for the acquiring company’s. Comparatively, it is observed that target companies CAAR value over the period of post-merger announcement until day 4 is higher than the merger companies CAAR value.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML