-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2016; 5(4): 171-183

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20160504.02

The Impact of Trade Protectionist Policy on the Economic Growth of Nigeria

Kingsley Okere1, Eugene Iheanacho2

1Department of Banking and Finance, Gregory University, Uturu, Nigeria

2Department of Economics, Abia State University, Uturu, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Kingsley Okere, Department of Banking and Finance, Gregory University, Uturu, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study examines the indirect impact of trade protectionist policy on economic growth in Nigeria by applying the bounds testing (ARDL) approach to cointegration over the period 1990 to 2013. Three measures of trade protectionist are used including real exchange rate, subsidy, trade openness and the indirect effect on economic growth was captured through unemployment and industrial production. The bound tests suggest that the variables of interest are bound together in the long run when unemployment and industrial production are the dependent variables. The associated equilibrium correction are also corrected and significant, confirming the existence of a long-run relationship. There is no evidence of long-run causal relationship between real GDP per capita, unemployment, labour and industrial production. There is evidence of short-run unidirectional causal relationship running from unemployment, industrial production to GDP per capita. There is unidirectional causal relationship running from GDP per capita and industrial to labour. Even though there is a general belief that trade protectionist policy is detrimental to growth, our empirical result fail to confirm this. However, we our finding reveals an indirect link between protectionist policy and economic growth through industrial production and the unemployment rate. The results found for Nigeria can be generalized and compared to other developing countries which share a common experience in managing the international exchanges of goods and services between national and regional economies.

Keywords: Trade protectionism, Unemployment, Industrial production, ARDL, Economic growth, VECM

Cite this paper: Kingsley Okere, Eugene Iheanacho, The Impact of Trade Protectionist Policy on the Economic Growth of Nigeria, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 5 No. 4, 2016, pp. 171-183. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20160504.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Protectionism consists of managing the international exchanges of goods and services between national and regional economies. This falls into regulation of imports and the management of exports, which itself is divided into export promotion and import controls. Recent studies have documented that trade restrictions are designed to protect domestic interests threatened by foreign competition. As a result, national governments have resorted to a growing range of measures aimed at supporting both small and large exporting companies, whether through technical assistance, or trade incentive. This however, has generated a lot of debate in the academic arena on whether trade protectionism policy really promote local industry and at the same time spur economic growth. Notable empirical studies in this debate are Grossman & Helpman, 1991; Matsuyama, 1992; Walde & Wood, 2005; Rodriguez & Rodrik, 2001; Yannikkaya, 2003) and most of these studies involve trade measures regarding export and import volumes or shares, trade policies regarding tariffs or custom barriers, and related measures of trade openness. Indeed, little or no attention has been given to the trade protectionism policy in the developing countries like Nigeria. Against this background, this article seek to analyze the impact of trade protectionism policy on the economic growth of Nigeria. To achieve this goal, we follow the work of Easterly, et el, (1997) and Frankel and Romer (1999) and first study various forms protectionism policy captured by tariff, quotes, export taxes and import taxes, we identify the variable that captures the economic growth in the like of real GDP per capita. Then we establish the transmission mechanism through which protectionism can affect real GDP per capita and this is captured by local industry productivity, unemployment rate, trade net-outflow. The cointegration relationship between trade protectionism policy and economic growth will be revealed. Finally, we studied the causality relationship between the variables. The rest of this article will be organized as follows; section 2, presents survey of the literature. Section 3, will discuss the methodology employed in the study, while section 4, analyses the empirical results. Finally, section 5, contains summary, conclusions, policy implication and recommendation.

2. A Theoretical and Empirical Review

2.1. Theoretical Review

- The relationship between trade protectionism and economic growth has been attributed to the potential positive externalities derived from exposure to foreign markets. More specifically, protectionism vis-a-vis export promotion strategy can be viewed as an engine of economic growth in three ways (Awokuse, 2008). First, export expansion can be a prime-mover for economic growth directly as a component of aggregate output. An increase in foreign demand for domestic exportable products can cause an overall growth in output via an increase in employment and income in the exportable sector. Second, export strategy can also affect growth indirectly through various routes such as: efficient resource allocation, greater capacity utilization, exploitation of economies of scale and stimulation of technological improvement due to foreign market competition (Helpman and Krugman, 1985). Export growth allows firms to take advantage of economies of scale that are external to firms in the non-export sector but internal to the overall economy. Third, expanded exports can provide foreign exchange that allows for increasing levels of imports of intermediate goods that in turn raises capital formation and thus stimulate output growth (Balassa, 1978; Esfahani, 1991). Relative to the case for export promotion strategy, expanded imports strategy have the potential to play a complementary role in stimulating overall economic growth. It is plausible to assume that the effect of protectionism vis-a-vis import promotion strategy on economic growth may be different from that of exports strategy. For instance, in many developing economies, imports provide much needed factors of production employed in the export sector. Also, the transfer of technology from developed to developing countries via imports could serve as an important source of economic growth. In the spirit of endogenous growth models imports can be a channel for long-run economic growth because it provides domestic firms access to foreign technology and knowledge (Grossman and Helpman, 1991; Coe and Helpman, 1995).

2.2. Review of Empirical Review

- Studies on the impact of protectionism on economic growth and in particular, export and import have enjoyed patronage in the advanced and emerging economies. At the forefront of this study are Dollar (1992), Ben-David (1993), Sachs and Warner (1995), Edwards (1998), Vamvakidis (1998), and Frankel and Romer (1999) are well-known studies that find a negative relationship between trade barriers (protectionism) and growth. Studies that fail to find a negative relationship between trade protectionism and economic growth are the studies of Harrison and Hanson (1999), Rodrik (1999), O'Rourke (2000), Rodriguez and Rodrik (2000), Irwin (2002), Yanikkaya (2003), and, to some extent, Vamvakidis (2002). Harrison (1996). The recent endogenous growth literature has reoriented the argument as to how openness enhances growth from focusing on exports to emphasizing imports of knowledge. Romer (1990) argues that imports give domestic producers access to a wider variety of capital goods, thus effectively enlarging the efficiency of production. The theories described in Grossman and Helpman (1991) suggest that the quality of intermediate products positively influences the efficiency of production. The new technology embodied in imported intermediate products renders imported products more productive and, therefore, increases labour productivity and total factor productivity (TFP). As a consequence, favourable trade protectionism will enhance growth only to the extent that a country trades with research-intensive economies. Researching further, the model of Barro and Sala-Martin (1995) considers a two-country world, where the technologically less advanced country taps into the knowledge of the technologically more advanced country. Provided that the costs of imitation are lower than the costs of innovation, the less advanced country will catch up to the more advanced country. Although most theories predict that growth is impeded by trade barriers, some models predict that, under certain circumstances, trade barriers may be good for growth (see, for instance, the discussion by Rodriguez and Rodrik 2000). Matsuyama (1992) shows examples in which countries that are sufficiently far behind the technological frontier may, through imports, be driven toward production of traditional goods and, consequently, experience a lower growth rate. A closely related argument is that the host country needs a sufficiently high capacity to absorb the technology developed in the technologically more advanced countries (see, for instance, Howitt 2000). These models underscore the importance of using a sample of countries that are technologically not too far apart. The countries used in this article are quite homogenous in terms of economic development, length of schooling, and technological knowledge. We would, therefore, expect the theoretical prior to go in the direction in which trade barriers are bad for economic growth. Furthermore, Vamvakidis (2002) argues that most studies find a positive relationship between growth and openness because the estimates rely predominantly on post-1970 data. Vamvakidis (2002) shows that the positive relationship between growth and openness is limited to the post-1970 period, and that no such relationship can be found in earlier data.

2.3. Unemployment and Trade Openness in an Economy

- The recent literature suggests a direct link between trade openness and unemployment. However, the effects of the degree of trade openness on the equilibrium unemployment rate are still not clear in the research arena (Bassanini and Duval 2006, 2009; Felbermayr, Prat, and Schmerer 2011b). Indeed, there are a great number of theoretical frameworks that drive a possible relationship between trade openness and unemployment. They are in likes of comparative advantage framework and product differentiation models of international trade. For instance, Davis (1998), Egger and Kreickemeier (2009), and Helpman and Itskhoki (2010) suggest that trade openness can destroy employment. In contrast, some scholars have suggested that trade openness reduces the unemployment rate; some examples of this strain of the literature are Matusz (1996), Revenga (1997). Finally, Sener (2001) and Moore and Ranjan (2005) concluded that trade openness has no effect and uncertain effects on unemployment, respectively.Following this study, Felbermayr, Prat, and Schmerer (2011a) calibrated a similar model, and they demonstrated that there is a significant long-run impact of trade openness on the unemployment rate. They also found a decreasing effect on unemployment rate as trade openness increases.

3. Data Sources, Definition of Variables and Model Econometrics Specification

3.1. Data Sources

- Annual time series data on economic growth, Trade openness, Real exchange rate, labor and capital stock covering the 1990– 2013 period have been used in this study. The data have been obtained from different sources, including Nigeria Central Bank annual reports, National Bureau of statistics (NBS) and the World Development Indicators (WDI) published online by the World Bank have been used to supplement the local data. The data corresponding to labor, trade openness, exchange rate subsidy, capital stock (gross fixed capital formation) are sourced from Central Bank Nigeria annual reports and NBS. The rest of the variables are sourced from WDI. Economic growth is measured by the increase of real GDP per capita in each successive time period. With respect to the variables capturing the transmission, we incorporate two variables into the analysis: industrial production and unemployment rate which are sourced from CBN.

3.2. Definition of Variables

- The variable real GDP per capita is noted by G. It is expressed in constant 1990 local current price. Subsidies obtained from CBN that measures all transfers from the central government to private and public enterprises as well as consumption subsidies. Since producer and export subsidies are only a fraction of GDP, the magnitude of the effects must be interpreted with caution. Trade openness (T) is the total sum of exports and imports divided by GDP; L is measured as the volume of the total labour force; capital investment (K) is measured by the real value of gross fixed capital formation (GFCF constant 1990 LCU).

3.3. Model Formulation

- The standard methodology of growth models begins with the neoclassical production function as revised by Solow (1956) and Iyoha (2000). We consider Cobb-Douglas production function of the form.

| (1) |

| (2) |

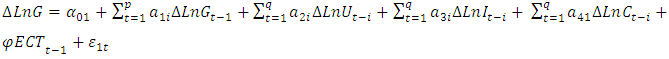

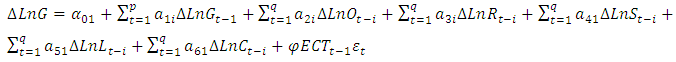

3.4. Specification of Model

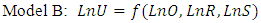

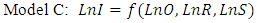

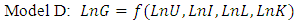

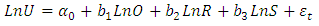

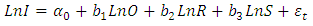

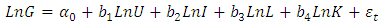

- Following model specification (ie eqt 1 and 2) four model is used to empirically examine the impact of protectionism on the economic growth of Nigeria:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

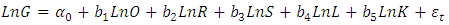

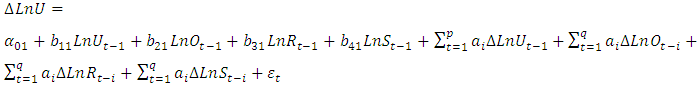

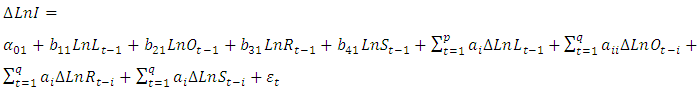

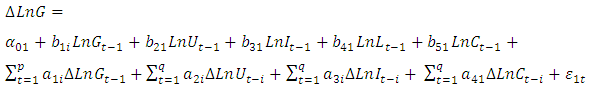

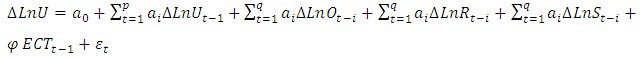

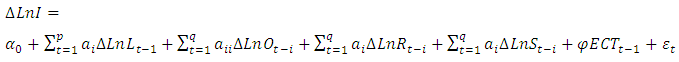

3.5. Econometric Specification of Model

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

4. Methodology

4.1. Unit Root Test

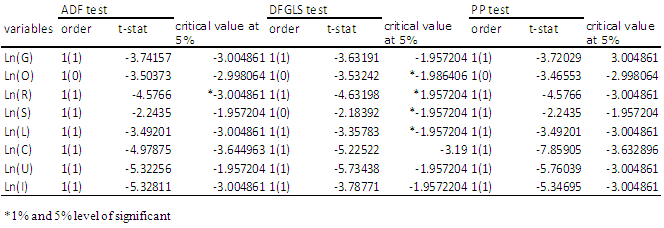

- In time series analysis, before running the cointegration test the variables must be tested for stationarity. For this purpose, we use the conventional ADF tests, the Phillips– Perron test following Phillips and Perron (1988) and the Dickey–Fuller generalized least square (DFGLS) de-trending test proposed by Elliot et al. (1996 The ARDL bounds test is based on the assumption that the variables are I(0) or I(1). Therefore, before applying this test, we determine the order of integration of all variables using unit root tests by testing for null hypothesis

(i.e

(i.e  has a unit root), and the alternative hypothesis is

has a unit root), and the alternative hypothesis is  . The objective is to ensure that the variables are not I(2) so as to avoid spurious results. In the presence of variables integrated of order two we cannot interpret the values of F statistics provided by Pesaran et al. (2001).

. The objective is to ensure that the variables are not I(2) so as to avoid spurious results. In the presence of variables integrated of order two we cannot interpret the values of F statistics provided by Pesaran et al. (2001).4.2. Cointegration with ARDL

- In order to empirically analyse the long-run relationships and short-run dynamic interactions among the variables of interest (Trade openness, Real exchange rate, labour, gross capital fixed formation, Unemployment, Industrial production and economic growth), we apply the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) cointegration technique as a general vector autoregressive (VAR).The ARDL cointegration approach was developed by Pesaran and Shin (1999) and Pesaran et al. (2001). This approach enjoys several advantages over the traditional cointegration technique documented by (Johansen and Juseline, 1990). Firstly, it requires small sample size. Two set of critical values are provided, low and upper value bounds for all classification of explanatory variables into pure I(1), purely I(0) or mutually cointegrated. Indeed, these critical values are generated for various sample sizes. However, Narayan (2005) argues that existing critical values of large sample sizes cannot be employed for small sample sizes. Secondly, Johensen’s procedure require that the variables should be integrated of the same order, whereas ARDL approach does not require variable to be of the same order. Thirdly, ARDL approach provides unbiased long-run estimates with valid t’statistics if some of the model repressors are endogenous (Narayan 2005 and Odhiambo, 2008). Fourthly, this approach provides a method of assessing the short run and long run effects of one variables on the other and as well separate both once an appropriate choice of the order of the ARDL model is made, (see Bentzen and Engslted, 2001). In this regard, Pesaran and Shin, (1999) explain that AIC and SC perform well in small sample, but SC is relatively superior to AIC. The ARDL model is written as follow;

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

is the first difference, and

is the first difference, and  are the error terms.

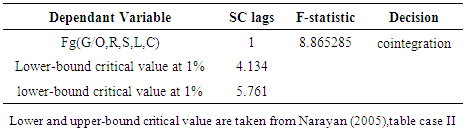

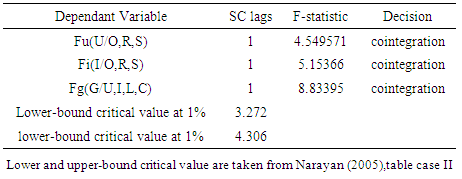

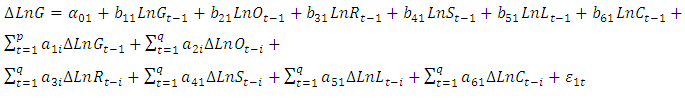

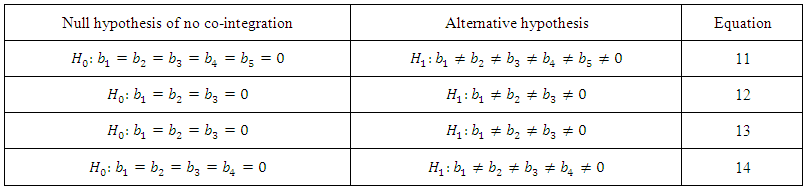

are the error terms.4.3. ARDL Bounds Tests Approach for Cointegration

- The bounds test is mainly based on the joint F-statistic whose asymptotic distribution is non-standard under the null hypothesis of no cointegration. The first step in the ARDL bounds approach is to estimate the four equations ((11)–(14)) by ordinary least squares (OLS). The estimation of the four equations tests for the existence of a long-run relationship among the variables by conducting an F-test for the joint significance of the coefficients of the lagged levels of the variables, i.e. The null hypothesis of no co-integration and the alternative hypothesis which are presented in figure A below as thus:

| Figure A |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

are the short-run dynamic coefficients of the model’s convergence to equilibrium and

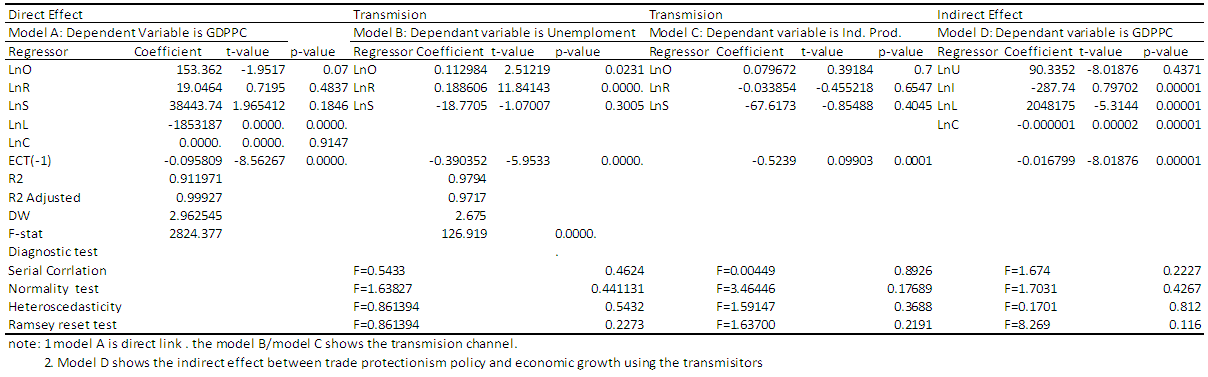

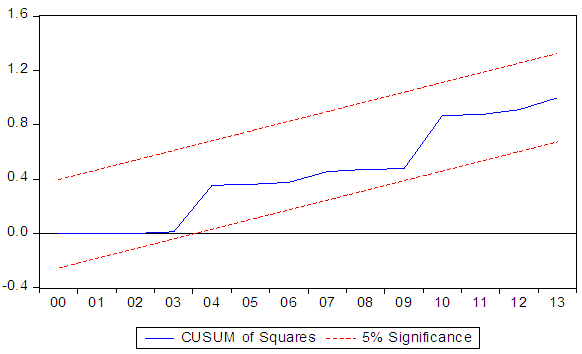

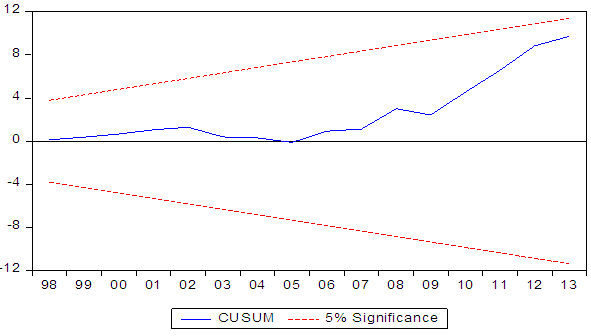

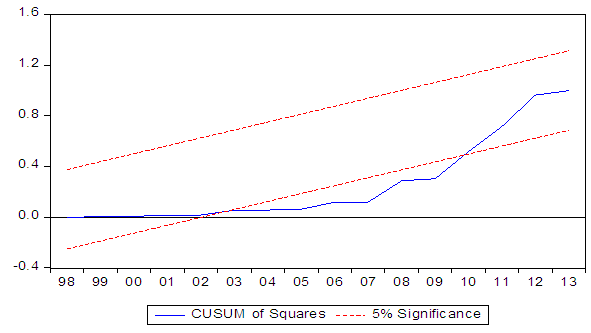

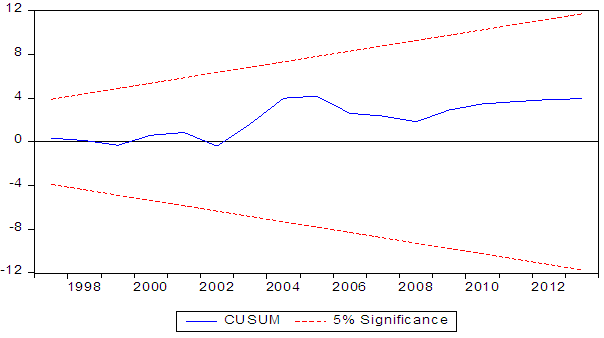

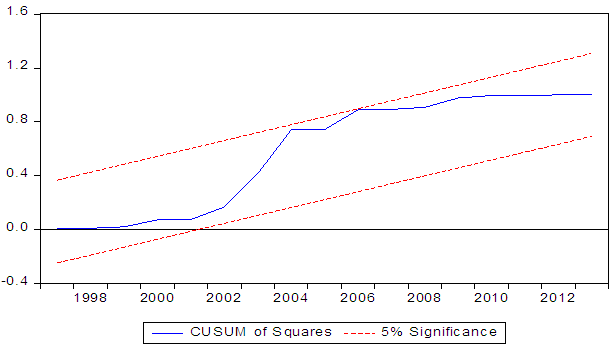

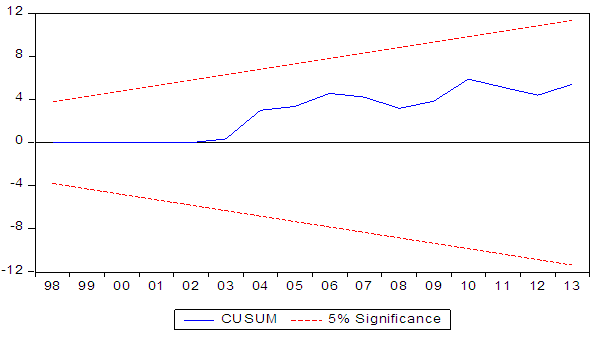

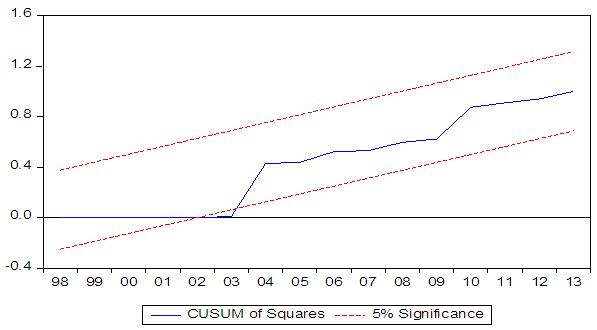

are the short-run dynamic coefficients of the model’s convergence to equilibrium and  is the speed of adjustment back to long-run equilibrium after a short-run shock.To ensure the goodness of fit of the model, diagnostic and stability tests are conducted. Diagnostic tests examine the model for serial correlation, functional form, non-normality and heteroscedasticity. The stability test is conducted by employing the cumulative sum of recursive residuals (CUSUM) and the cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals (CUSUMSQ) suggested by Brown et al. (1975). The CUSUM and CUSUMSQ statistics are updated recursively and plotted against the break points. If the plots of the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ statistics stay within the critical bonds of a 5 percent level of significance, the null hypothesis of all coefficients in the given regression is stable and cannot be rejected.

is the speed of adjustment back to long-run equilibrium after a short-run shock.To ensure the goodness of fit of the model, diagnostic and stability tests are conducted. Diagnostic tests examine the model for serial correlation, functional form, non-normality and heteroscedasticity. The stability test is conducted by employing the cumulative sum of recursive residuals (CUSUM) and the cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals (CUSUMSQ) suggested by Brown et al. (1975). The CUSUM and CUSUMSQ statistics are updated recursively and plotted against the break points. If the plots of the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ statistics stay within the critical bonds of a 5 percent level of significance, the null hypothesis of all coefficients in the given regression is stable and cannot be rejected.4.4. Granger Causality Test

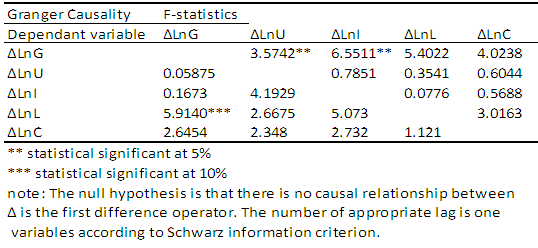

- The ARDL co-integration approach tests the existence or absence of co-integration relationship between variables, but it does not indicate the direction of the causal relationship between the variables. Therefore, the two-step procedure of the Granger (1988) model is employed to examine the causal relationship among the variables. The test answers the question of whether X causes Y or Y causes X. X is said to be Granger caused by Y if Y help in the prediction of the present value of X or equivalently, if the coefficients on the lagged Ys are statistically significant. To test for Granger causality in the long-run relationship, we employed a two-step process: The first step is the estimation of the long-run model for Equation (5)-(8) in order to obtain the long-run relationship as error correction term (ECT) in the system. The next step is to estimate the Granger causality model with the variables in first differences and including the ECT in the systems.

5. Empirical Result and Discussion

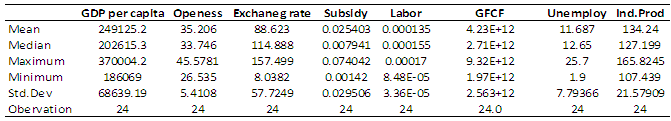

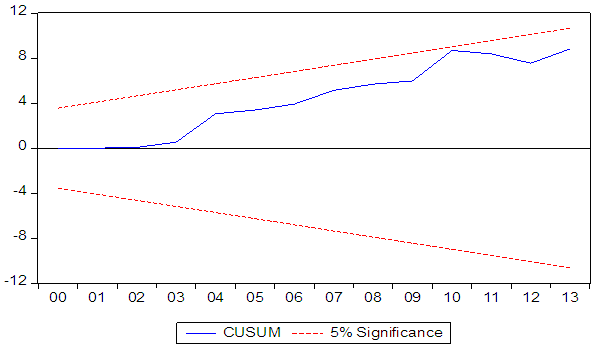

- The results of the stationarity tests show that some of the variables are nonstationary at level. Therefore, ADF, Phillips–Perron and DF-GLS tests applied to the first difference of the data series reject the null hypothesis of non-stationarity for the variables used in this study (see Table 2). The result for both the level and differenced variables are presented in table 2.The stationary tests were performed first in level and then in first diIt is therefore worth concluding that all the variables are integrated of order one.The summary statistics of all variables are given in Table 1.

|

|

|

|

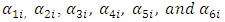

| Table 5. Estimated long-run coefficient for the four model using the ARDL approach |

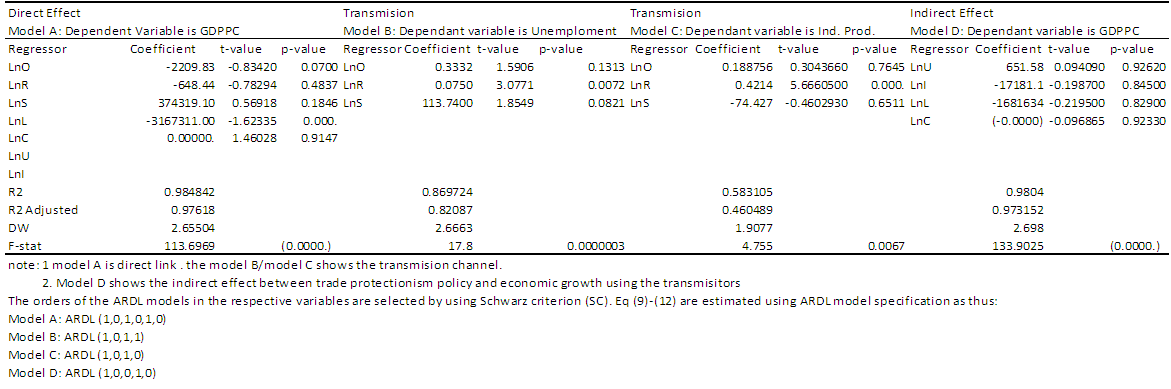

| Table 6. Estimated Short-run coefficients for the four model using the ARDL approach |

|

| Figure 1. Plot for the CUSUM |

| Figure 2. Plot for the CUSUMSQ |

| Figure 3. Plot for the CUSUM |

| Figure 4. Plot for the CUSUMSQ |

| Figure 5. Plot for the CUSUM |

| Figure 6. Plot for the CUSUMSQ |

| Figure 7. Plot for the CUSUM |

| Figure 8. Plot for the CUSMSQ |

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

- This paper examines the impact of trade protectionist policy on economic growth for Nigeria using annual data for the period of 1990-2013. The ARDL bounds testing approach to cointegration has been employed for establishing the long-run and short-run dynamics. To check for the direction of causality among the variables, dynamic VEC model in used.The ARDL bounds test for cointegration produces evidence of a long-run relationship between real GDP per capita, unemployment, industrial production, labour, capital, trade openness, and subsidies. The result also support the claim that trade protectionist policy vis-à-vis export promotion strategy and unemployment are the prime-mover for economic growth of Nigeria especially in the short run. It implies that the level of trade protection in Nigeria has a direct relationship with growth and unemployment in short-run but negative or inverse relationship in the long-run. This could be as result of series of government policies especially the case of high tariff on the importation of cars and the limit to employment on expatriates. This study also explores causal relationship between the variables by using error-correction based granger causality models. The result Granger causality can be summarised as follows: There is no evidence of long-run causal relationship between real GDP, unemployment, labour and industrial production. There is evidence of short-run unidirectional causal relationship running from unemployment an industrial production to GDP per capita. There is unidirectional causal relationship running from GDP per capita and industrial to labour. Even though there is a general belief that trade protectionist policy is detrimental to growth, our empirical result fail to confirm this.The present study has found evidence that trade protectionist policy has great direct impact on economic growth for Nigeria through some selected variables. These findings suggest some lessons regarding policies related to local content act, new tariff, quotas and ban. High level of these variables in addition with the ones analysed in this study have led to indirect impact between trade protectionist and economic growth in Nigeria. The study also suggests suggest some policy implications. Since our result reveals transmission link in only run, it appears that economic stagnation suffered in the long-run cannot be attributed to trade protectionist policy. More generally, our results lead support to the idea that policies are designed to promote growth.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML