-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2016; 5(1): 1-12

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20160501.01

An Empirical Analysis of Market Timing Performance of Indian Asset Management Companies under Unconditional Model

Dhanraj Sharma

Department of Commerce, Central University of Rajasthan, Ajmer, India

Correspondence to: Dhanraj Sharma , Department of Commerce, Central University of Rajasthan, Ajmer, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This main purpose of the research is to examine the market timing and stock selection abilities of the Indian Asset Management Companies (AMC’s) from April 2000 to March 2014. To achieve the major objective of the study, unconditional market timing techniques are applied on a sample size of 62 mutual fund schemes developed by Treynor & Mazuy (1966) and Henriksson & Merton (1981). The research also characterized the results on the basis of institutional sponsorships and investment objectives of the sample mutual fund schemes managed by asset management companies. The study confirms the presence of stock selection abilities but Indian asset management companies do not exhibit the market timing abilities to create additional value to the managed funds within the study period.

Keywords: Portfolio evaluation, Stock selection, Market timing, Asset management companies

Cite this paper: Dhanraj Sharma , An Empirical Analysis of Market Timing Performance of Indian Asset Management Companies under Unconditional Model, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 5 No. 1, 2016, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20160501.01.

1. Introduction

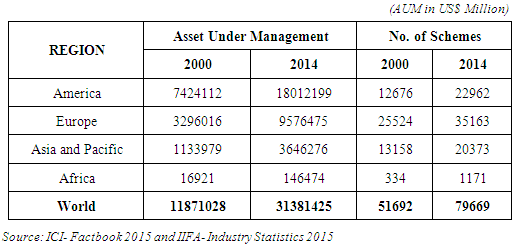

- The Indian capital market witnessed unprecedented growth and development since globalization and these developments relate to innovation of financial instruments and one such preferred investment option is mutual funds. Mutual fund is an investment vehicles created by asset management companies, specializing in pooling saving of both retail and institutional investors (Abdullah, Hassan & Mohamad, 2007). The asset management industry plays an important role in the financial intermediation of investible funds in the capital market. Global Asset management industry has witnessed a remarkable growth during last fifteen years. As per the periodical report revealed by Investment Company Institute (2015) and International Investment Fund Association (2015), Asset under Management (AUM) of the worldwide industry increased to $31.38 trillion at the end of fourth quarter of 2014. The America region has the largest contribution in the AUM and numbers of schemes as it hold $ 18.01 trillion of AUM and 22962 of mutual fund schemes. The America region is followed by Europe, Asia and Pacific and Africa. The AUM of the Asia Pacific was $3.64 trillion which increased by more than 3 times as compared to figure of the year 2000. These statistics confirmed the increasing dominance of the emerging market of Asia Pacific in the global asset management industry.Stock selection and market timing is the two important component in the performance evaluation of asset management company. Deb, Banerjee, & Chakrabarti (2007) defined the market timing as skills imply assessing correctly the direction of the market, whether bull or bear and positioning their portfolio accordingly and stock selection skills as a process of micro forecasting which generally forecasts price movement that are under or overvalued relative to stock identification of individual stocks that are under or overvalued relative to equities in general. In simple terms Oueslati, Hammami & Jilani (2014) explained selectivity skills as the ability of the fund managers to pick up undervalued assets whereas the market timing skills denote to predict future market fluctuations.The evaluation of the performance of asset management companies has the prominent importance for the academicians and investors. The popularity of investment in mutual fund schemes managed by these companies has grown dramatically since the private sector companies were allowed to enter in the market. India steadily emerged as a center of attractive investment opportunities, owing to high GDP growth rate and rising level of per capita income. The asset management industry is one of the fast growing sectors in India since economic reforms in 1991. The asset under management (AUM) of Indian asset management companies increased from Rs. 90587 crore (3.85 per cent of the GDP) in 2000-01 to Rs. 905120 crore (15.74 per cent of the GDP) in 2013-14. The growth of the industry provide wide variety of investment option to the investors since there are 1638 mutual fund schemes at the end of March 2014. The penetration of the industry also shows the remarkable growth over the period of time. This research mainly focused on the research problem that whether the investment performance of Indian Asset Management Companies provides risk adjusted return to the investors and whether they were able to time the market effectively during the study period. The study aims to find out whether asset management companies are able to add the value in the investment with their stock selection and market timing strategies. The study contributes in providing an analytical framework to assess the performance of Indian AMC’s in capital market since 2000. This research paper consists of five sections which starts with introduction and followed by brief review of relevant existing studies. The next section provides the methodology followed by empirical result of the research based on models developed by Treynor & Mazuy (1966) and Henrsiksson & Merton (1981). The final section presents conclusion of the research paper.

|

2. Literature Review

- It is always a difficult practice to adopt the appropriate evaluation models to assess the performance of portfolio managed by asset management companies. Some of the important studies which develop evaluation techniques include Treynor (1965), Sharpe (1966), Jensen (1968) and Fama (1972). Jensen (1968) is the most widely used and heavily criticized performance technique in comparison with Treynor (1965) and Sharpe (1966). Some of the critiques were Admati & Ross (1985), Dybvig & Ross (1985), and Grinblatt & Titman (1989). Argument was given as study of Jensen classifies the successful market timers as poor performers. The pioneer contribution in the field of portfolio evaluation was given by Treynor & Mazuy (1966) and Henriksson & Merton (1982) who developed a model to test the market timing ability of asset management companies. Treynor & Mazuy (1966) studied the 57 US growth and balanced mutual fund schemes during the period of 1953 to 1962 and proposed a model which is extension of Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) propounded by Jensen (1968). They concluded that there is no statistical evidence that funds managers have successfully outguessed the market. Henriksson & Merton (1982) conducted a study with an objective to develop more qualitative approach of measuring the market timing. There were 67 sample mutual fund schemes analyzed for the period of 1968 to 1980. They suggested that the parametric test could be used without assumptions on distribution of portfolio returns if any asset management company has an ability to forecast the future observation. Apart from these benchmark studies, a rich literature reported a very little presence of market timing ability of fund manager such as Chang and Lewellen (1984), Chua and Woodward (1986), Sinclair (1990), Gallo and Swanson (1996), Chen, Ferson and Peters (2003), Jiang, Yao & Yu (2007). Jiang (2001) proposed a nonparametric test for market timing ability of fund managers to analyze large sample of mutual funds that have different bench mark indices. In the most recent studies, Bodson, Cavenaile & Sougne (2013) globally investigated the market timing abilities of fund managers from the perspective of market return, market wide volatility and aggregate liquidity. They found very few schemes display market timing skills.In the major recent studies, Angelidis T. et al. (2013) introduced a new factor exposure based approach for measuring the static and dynamic timing capabilities of asset managers. The research suggested that evaluating stock selection skill and market timing ability in a way that was consistent with common asset management practices. They concluded that earlier studies were failed to measure skill stock selection and market timing because they ignore the manager’s self-reported benchmark in the performance evaluation process. Skrinjaric T. (2013) attempted to find evidence of market timing abilities of Croatian funds estimating He selected the sample of ten funds based on highest assets in 2010 and 2011 in Croatia and monthly data was collected from December 2002 to November 2011 for analysis. The result had indicated a lack of market timing abilities of selected funds and the reason was lack of good forecasting abilities and presence of defensive behavior. Eleonora G. (2012) in their research evaluated the performance of 220 open ended equity mutual funds of European countries (from weak and strong economies) for a period of 8 years from January 2004 to December 2011. He split the study period in two four year sub periods in order to examined their performance prior to global financial crisis and after its brunt in 2008. He found that fund managers reported absence of market timing, no mutual fund showed abnormal returns and information ratio indicated that only Italian fund managers had stock picking abilities. Sheikh M. J. & Noreen U. (2012) analyzed the performance of the fund managers of U.K. and their market timing abilities. The study employed two widely accepted performance measurement techniques i.e. Jensen alpha measure and Treynor and Mazuy market timing hypothesis. They concluded that the fund managers lacked the ability to predict the market movement on consistent bases. They were unable to outperform the market and could not beat the benchmark. They found that fund managers also lack market timing abilities which support the efficient market hypothesis proposed by Fama and any chance of outperforming the market was merely a random chance and this could not be done on consistent bases. Villadsen M. (2011) provided a performance analysis of 60 Danish mutual funds in the period from 2001-2009. This study includes the investment performance measures and market timing models (T&M Model) to evaluate the performance of sample mutual fund schemes. It was found that 8 mutual fund schemes investing in Danish stocks showed significant timing abilities and in remaining schemes timing abilities were nort present. In the country specific studies Dieu (2015) in French market, Mushah, Senyo, & Nuhu (2014) in Ghana market, Cuthberston & Nitzsche (2014) in German, Afza & Rauf (2009) in Pakistan, Cuthbertson, Nitzsche & Sullivan (2006) in UK, Kader & Qing (2007) in Hong Kong, Lhabitany (2001) in Swiss market, Dewi & Ferdian (2012) in Malaysia, Philippas (2002), Low (2012) in Greek market, Ashraf (2013) in Saudi Arabia, Christensen (2005) in Danish market found very less evidence of market timing ability of fund managers to generate additional value of the investors. In the Indian context some efforts are made to evaluate the market timing ability of Asset management companies. Ramesh & Dhume (2014) analyzed the market timing ability and stock selection skills of Indian fund managers based on 68 open ended mutual fund schemes and concluded that Indian mutual fund managers were not good at timing the market whereas they possess excellent stock selection skills for choosing the portfolio. Zabiulla (2014) examined the portfolio strategy of Indian fund managers and the impact of asset size and market capitalization on the fund performance and found that fund managers did not exhibit any stock selection skills and market timing ability to provide additional value to the investment. Tripathi (2006) Deb, Banerjee & Chakrabarti (2007), Sondhi & Jain (2006), Bhuvaneswari & Selvam (2011) found the insignificant performance of market timing abilities of asset management companies. Dhar & Mandal (2014) revealed that majority of the fund managers were unable to time the market correctly during the study period and suggested that conditioning only the public information improves the coefficient of determination. Roy & Deb (2004) examined the effect of incorporating lagged information variables into the evaluation of performance of fund manager. They suggested that the use of conditioning lagged information variables improves the performance of the mutual funds, causing the alphas to shift towards the right and reducing the number of negative timing coefficient. Some studies like Bollen & Busse (2001), Jiang, Yao, and Yu (2007), Huang & Wang (2010) and Cao, Chen, Liang, & Lo (2011) are the exception to the literature in the evaluation of the performance of fund managers found significant market timing ability.The literature review provides the need to conduct the research specially in Indian context. Bollen and Busse (2001) suggested that daily data are significant to draw the inferences than monthly and yearly data. In the Indian context, very few studies conduct the study based on daily data. Present study used daily frequency to evaluate the marketing ability of asset management companies. In this study result is also presented in sponsorship institution and objective classification of sample mutual fund schemes. The sample size and study period is also relatively large compared with earlier studies in order to provide meaningful observation. Therefore present study is an attempt to fill the uncovered area of existing literature.

3. Methodology

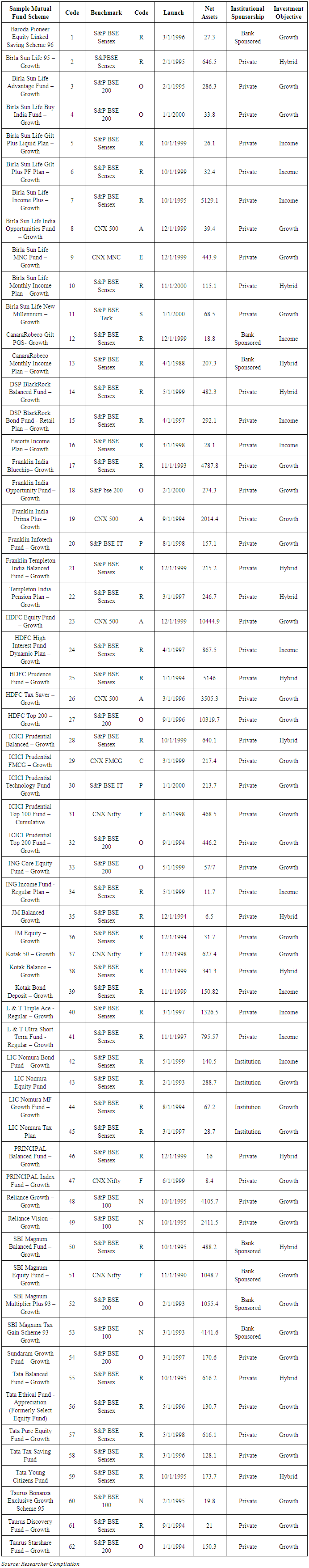

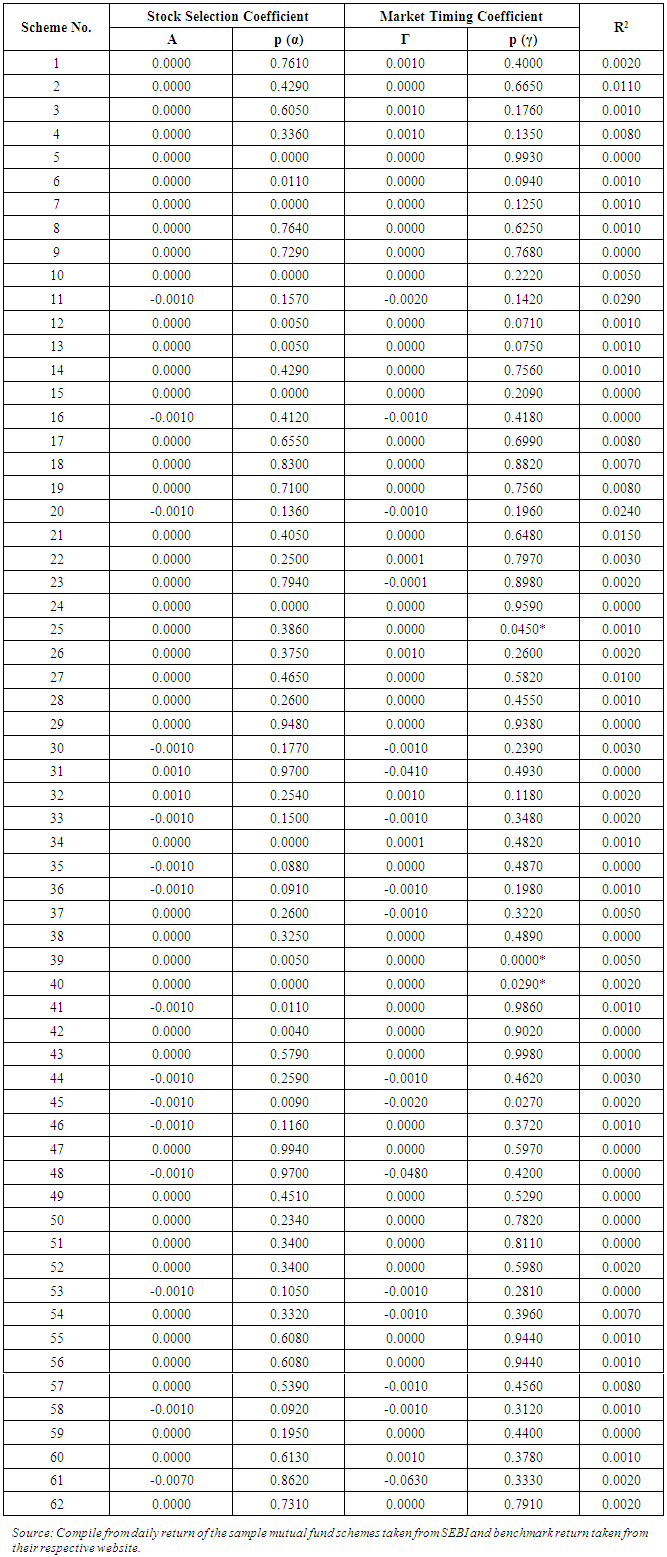

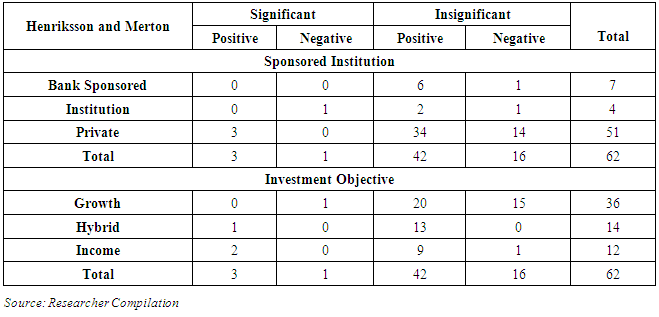

- Sample SchemesThe study followed purposive sampling and the basic purpose is to draw the inferences on the basis of consistent samples which are in existence during entire study period. The samples mutual fund schemes are selected on the basis of schemes operating in the entire study period. First the asset management companies are selected which are in operation from 2000-01 to 2013-14. Than schemes are identified which are operating during the whole study period for selected companies. The study used a sample of 62 mutual fund schemes which belong to 19 Asset Management Companies, related to Bank sponsored, Institution and Private asset management companies. While 7 schemes from three bank sponsored companies, 4 schemes from one Institution companies and 51 schemes have taken from fifteen private asset management companies. Investment objective wise classification of the 62 schemes involves 36 growth schemes, 14 hybrid schemes and 12 income schemes. For the convenience in analysis, code is allotted to the sample mutual fund schemes and benchmark index. The details relating to the sample schemes and their respective benchmark index are given in Table 2.

|

4. Empirical Results

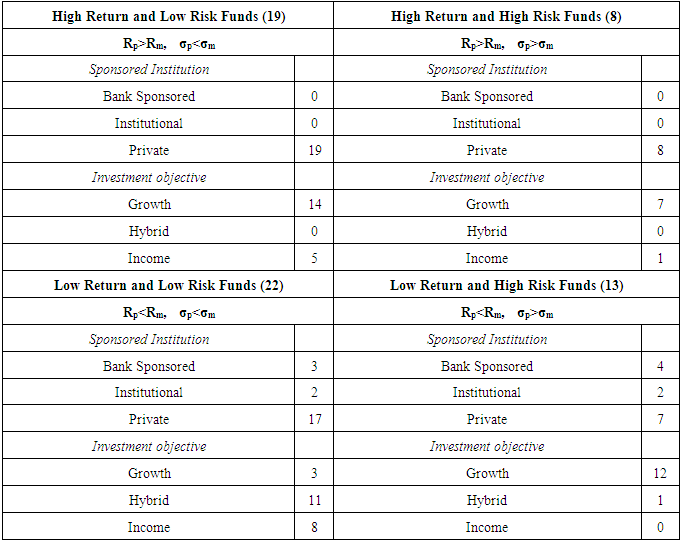

- This matrix is given in Table 3 gives a clear idea of risk-return relationship of all the samples in relation to the benchmark portfolio. The investor can link his investment to the quadrants on the lines of matrix. It can be clearly observed that all the bank sponsored and institutional schemes belong to low return quadrants and the majority of the private asset management schemes relate to high return segment. In the objective classification, most of the growth schemes provide high return while taking low and high risk while all hybrid and majority of the income schemes follows the low risk strategy. The finding of risk and return matrix of Zabiulla (2014) was consistent with the Fama & French (1992) confirmed that high return may be attainable by portfolio having low risk. In the present study 13 sample schemes provide high return and taking low risk and most of the schemes belong to private asset management companies.

|

|

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

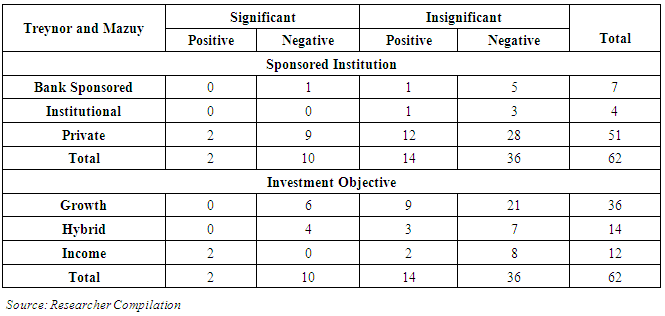

- In this paper, forecasting and market timing abilities of Indian asset management companies are examined with the help of models proposed by Treynor & Mazuy (1966) and Henrisksson & Merton (1981) with a sample size of 62 mutual fund schemes. The results are also categorized in sponsorship institutions (Bank sponsored, Institution and Private Asset management companies) and investment objectives (Equity, Income and Hybrid schemes). The analysis reveals that superior performance of sample mutual fund schemes during the study period have occurred due to stock selection ability of asset management companies rather than their market timing abilities. The result pertaining to market timing abilities of asset management companies in terms of both the two models- Treynor & Mazuy and Henriksson and Merton, do not support the hypothesis that Indian Asset management companies are able to time the market correctly. From the analysis we found that mutual fund schemes are able to time the market but in wrong direction and few schemes are able to time the market correctly. Zaibulla (2014) concluded in their study that fund manager failed to position their portfolio to take advantage of stock market trends during the economic cycle. The result of the present study is consistent with earlier studies which also found poor performance of poor market timing ability of asset management companies in India over a period of 2001-2014. This study is not free from limitations as it is restricted to the sample of 62 mutual fund schemes related to 19 asset management companies in India Another limitation is some of the benchmark indexes are established after the commencement of study period. In place of such indexes S&P BSE 30 index is used as a benchmark proxy All the official sources, from where the data has been taken do not provide the complete data. The data available is only for the recent three or five years which is not enough to conduct a research. This study based on the data provided by corporate bodies. Research is continuous process that provides opportunities for future researches. This research confine to portfolio performance measures and unconditional model of market timings, however future researches may apply conditional model of market timing, DEA techniques, Fama- French three factor models and Carhart four factor models. The research can be conducted on the different categorization such as on the basis of investor’s preferences (SIP, SWP, and STP), schemes based on capitalization (Large Cap, Mid cap and Small cap) and special schemes like Exchange Traded funds, Fund of Funds, Index Funds, Money Market Funds and Offshore Funds.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML