-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2015; 4(6): 333-338

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20150406.03

A Comparative Study on Beta in Islamic Finance: Evidence from Malaysian Stock Exchange

Nicola Miglietta, Enrico Battisti

Department of Management, University of Turin, School of Management and Economics, Turin, Italy

Correspondence to: Enrico Battisti, Department of Management, University of Turin, School of Management and Economics, Turin, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The aim of this paper is to provide some preliminary evidences on the potential effect on the risk as result of the principles used to divide the companies between Shari’ah Compliant (LCSC) and not Shari’ah Compliant (LCnotSC). In particular, this analysis represents an exploratory study based on the comparison between the Beta of a sample of companies listed on Bursa Malaysia, classified according to the principles of Islamic finance (business activity screen and financial ratio screen). The results of our analysis point out that in the Malaysian Stock Exchange there is a prevalence of listed companies Shari’ah Compliant that have, on average, a level of risk (measured by Beta) higher than the not Shari’ah Compliant listed companies in the same market.

Keywords: Beta, Leverage, Principles of Islamic Finance, Capital Structure, Malaysian Stock Exchange

Cite this paper: Nicola Miglietta, Enrico Battisti, A Comparative Study on Beta in Islamic Finance: Evidence from Malaysian Stock Exchange, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 4 No. 6, 2015, pp. 333-338. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20150406.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Islamic finance – refers to a set of legal institutions, financial instruments, practices, transactions and contracts that operate in accordance with the dictates of Islamic Jurisprudence (Shari’ah) – grown rapidly over the past decade. It represents, in relative terms, more than 1% of the financial world, but is becoming increasingly significant within the global financial system, with an annual growth rates in between 10% and 15%. In early 2015, the market value of all funds managed by Islamic financial institutions (Assets Under Management) amounted to about $ 2 billion. This value is up from $ 1.8 billion recorded in the first months of 2014. In particular, it should be highlighted that the fundamental precepts contained in the Shari’ah do not have significance to the sole sphere of the relationship in between man and God, but represent also the principles of conduct applied in all sectors and areas of public life of the community of believers because they oversee the regulation of every economic activity.The central key of the Islamic finance is not the religion, but the “economic justice” that is inspired by the Islamic ethics.Synthetically, the main requirements for financial matters are related to the prohibition of a fixed and predetermined interest rate (ribā), guaranteed regardless of the performance of the investment (the theory of Profit and Loss Sharing), the prohibition to implement economic practices involving uncertainty (gharār) and speculation (maysīr), the prohibition to use, to invest and to trade in goods or activities prohibited (harām).According to the dictates of the Islamic law, there is freedom in the activity and business negotiation although the ability to enter into agreements between the parties can be exercised only within certain limits.The Traditional Principles of Corporate Finance postulate that each firm carries out some choices related to where to get the funds (investment decision), how to invest those (financing decision) and when to return the returns (dividend decision). The same choices can be referred to an Islamic firm [3].We can therefore assert that the financial goal of the firm is to maximize the Shareholder Value. This goal is widely accepted in both theory and practice [1-5] and can be applied to Islamic firms [6-9, 19]. What is different? Moreover, why? The principles that a Shari’ah Compliant company must follow with reference to its capital structure diverge from a traditional firm. In particular, Profit and Loss Sharing (PLS), Musharakah, Mudarabah, Sukuk and Mark-up financing, in addition to legal-religious principles, could play a significant role on the system of capital structure puzzle and, consequently, on the Beta (measure of market risk). The aim of this paper is to provide some preliminary evidences of the potential effect on the risk as result of the principles used to divide the companies between Shari’ah Compliant (LCSC) and not Shari’ah Compliant (LCnotSC). The paper is organised as follows. First, we introduce a theoretical background of the Islamic Finance. After we analyse a sample of companies listed on Malaysian Stock Exchange, classified and shared according to the principles of Islamic finance (quantitative and qualitative criteria) in order to observe some financial ratio (Debt over Equity and Debt over Total Assets) and to know the different level of risk (Beta).Finally, we conclude by discussing the results and possible future applications of Beta in relation to capital structure.

2. Theoretical Background

- Islamic finance is defined as a financial system that operates according to Shari’ah and is, consequently, Shari’ah Compliant [9]. Islamic Finance is based on core concepts of balance, which help ensure that the reasons and objectives driving the Islamic industry are beneficial also for the society. It is one of the most growing segments of the global finance industry [21]. As demonstrated by the global proliferation of Islamic financial institutions, Islamic financial markets have gained impulse over the past few years; this proliferation has been accompanied by parallel increases in Islamic financial products. The principles of Islamic finance have been analyzed by Muslim and not-Muslim researchers alike [10-13, 20] but the number of literatures focusing on Islamic finance from the point of view of corporate finance is scant [6-8]. Islamic finance is based on the legal-religious principles of Shari’ah, geared mainly to illustrate what not to do rather than on what is lawful to do [14]. The most important sources of Shari’ah are [21]:− Holy Quran refers to the book of revelation given to the Prophet Muhammad; − Hadith is the narrative relating to the deeds and utterances of Muhammad; − Sunna is the habitual practice and behaviour of Muhammad during his lifetime; − Ijma refers to the consensus between religion scholars about specific issues not envisaged in either the Holy Quran or the Sunna; − Qiyas is the practice of deduction by analogy to provide an opinion on a case not referred to in the Quran or the Sunna in comparison with another case referred to in the Quran and the Sunna; − Ijtihad represents a jurists’ independent reasoning relating to the applicability of certain Shari’ha rules on cases not cited in ether the Quranor the Sunna.Islamic financial system requires transactions to be linked to the real sector, leading to fruitful activities that produce income and wealth [15]. In particular, the aim of Shari’ah is to promote actions that do not affect people and society adversely through the violation of religious bans.The main principles of Islamic finance are:− the prohibition of Riba (generally translated as usury or interest) and the exclusion of debt-based financing from the economy; − the prohibition of Gharar (generally translated as risk, uncertainty or hazard) encompassing the full disclosure of information and elimination of any asymmetrical information in a contract; − the prohibition of Maysir (generally translated as gambling or other games of chance) encompassing the exclusion of financing and dealing in sinful and socially irresponsible activities and commodities such as gambling, drugs and pork or the production of alcohol and other games of chance (i.e. casino-type games, lotteries); − materiality (a financial transaction needs to have a ‘material finality’) that is a direct or indirect link to a real economic transaction. Islamic finance supports people to invest their cash effectively without any wrongdoing for those who are either borrowers or lenders;− justice, a financial transaction should not lead to the utilization of any part to the transaction.Islamic finance rejects that a gain can be realized without taking a risk. The funding to the business entity is permitted, but the return must be tied exclusively to the results linked to the use of capital [16]. This is the base of the Profit and Loss Sharing that is a form of partnership, where partners share profits and losses based on their capital share and work. In particular, the concept of PLS is the method utilized in Islamic banking to comply with the prohibition of interest and it is a contractual agreement between two or more transacting parts, which allows to bring together their resources to invest in a project to share in profit and loss [10].

3. A Comparative Study on Beta

3.1. Methodology

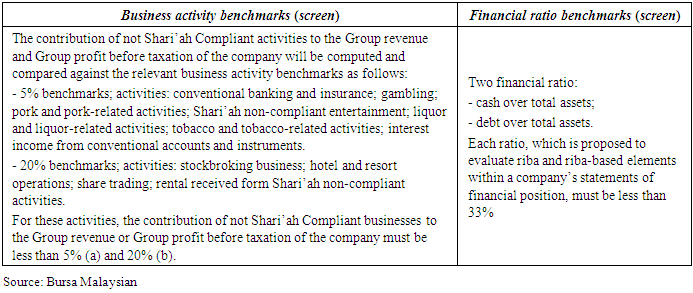

- Shari’ah Compliant screening criteria have been adopted by Islamic Financial Institutions around the world. Fundamentally, the criteria consist of two different levels [22], [23]:− qualitative: business activity screen; an enterprise must derive its revenue or profit from Shari’ah Compliant activity.− qualitative: financial ratio screen; a company would be accepted as Shati’ah Compliant if it meets the criteria set in terms of liquidity ratio, debt ratio, interest screen and others non-permissible income screen.In particular, based on the Shari’ah Advisory Council (SAC) of the Securities Commission of Malaysia, we have considered not Shari’ah Compliant all the companies involved in the following core activities: − financial services based on riba (interest); − gaming and gambling; − manufacture or sale of non-halal products or related products; − conventional insurance; − entertainment activities that are non-permissible according to Shari’ah; − manufacture or sale of tobacco-based products or related products; − stock broking or share trading on Shari’ah non-compliant securities; − Other activities deemed non-permissible according to Shari’ah. For firms with activities comprising both permissible and non-permissible activities, the SAC measures the level of mixed contributions from permissible and non-permissible activities towards turnover and profit before tax of a company [17]. The SAC uses benchmarks based on Ijtihad. In particular, the Shari’ah Advisory Council applies a two-tier quantitative approach in determining the Shari’ah Compliant status of the listed securities: business activity benchmarks and financial ratio benchmarks (see the site of of Bursa Malaysia Stock Exchange and the table 1).

|

| Figure 1. Sample of listed companies analyzed |

3.2. Data Analysis and Findings

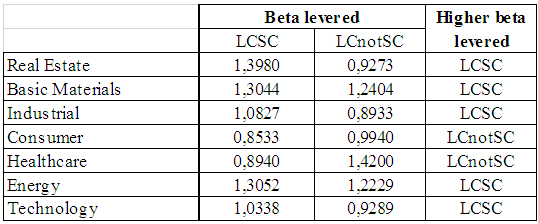

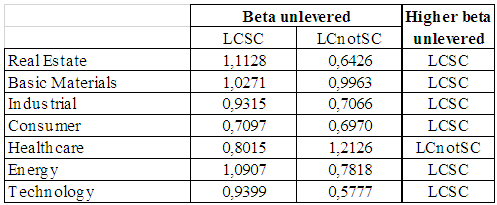

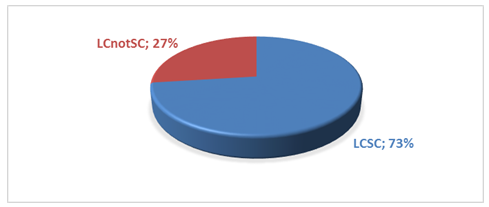

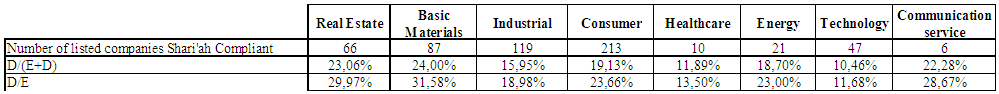

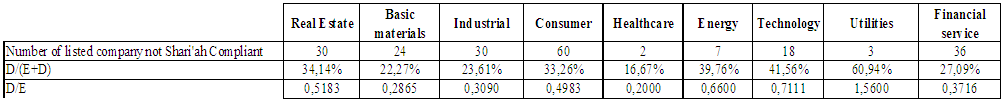

- From the sample of firms analysed, we have divided the undertakings by macro sectors: − 8 for the listed companies which are Shari’ah Compliant;− 9 for the listed companies which are not Shari’ah Compliant.For the LCSC sectors, the companies considered are 6 for Communication Service, 10 for Healthcare, 21 for Energy, 47 for Technology, 66 for Real Estate, 87 for Basic Materials, 119 for Industrial and 213 for Consumer:For the LCnotSC sectors, the companies analyzed are 2 for Healthcare, 3 for Utilities, 7 for Energy, 18 for Technology, 24 for Basic Materials, 30 for Real Estate, 30 for Industrial, 36 for Financial Services and 60 for Consumer.Both for Shari’ah Compliant listed companies and for those not Shari’ah Compliant, the macro sector that has the highest number of listed companies is “Consumer”.In order to provide some preliminary evidence of the potential effect on the risk as result of the principles used to divide the companies between LCSC and LCnotSC, we have decided to analyse for each listed companies the following elements: − Debt over Equity,− Debt over Total Assets,− Beta levered, − Beta unlevered.In the first part we have calculated the leverage ratio and debt over total assets for Shari’ah Compliant listed companies and for not Shari’ah Compliant and, based on Damodaran data, we have considered a Malaysian tax rate of 14,50% [18]. The results are the following (table 2 and 3).

| Table 2. Number of listed companies, Debt/Equity ratio and Debt/Total Assets ratio of LCSC |

| Table 3. Number of listed companies, Debt/Equity ratio and Debt/Total Assets ratio of LcnotSC |

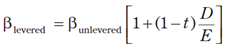

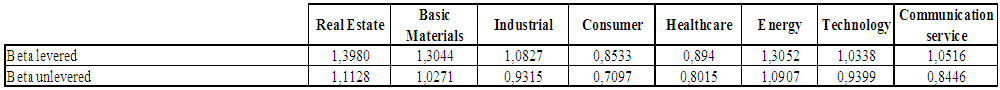

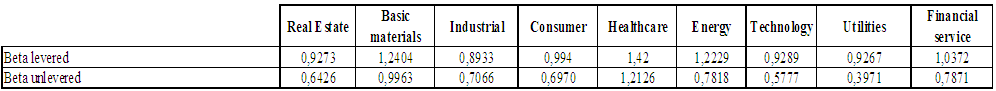

where − t = tax rate − D/E = Debt over Equity (financial debt/equity market capitalization).The results are the following (table 4 and 5).

where − t = tax rate − D/E = Debt over Equity (financial debt/equity market capitalization).The results are the following (table 4 and 5). | Table 4. Beta levered and unlevered of LCSC |

| Table 5. Beta levered and unlevered of LCnotSC |

|

|

4. Conclusions and Directions for Further Research

- There has been incredible interest in Islamic finance, particularly in the past decade, due to the rapid pace of growth in Islamic financing and investments [22]. In this sense, this preliminary research highlights that in the Bursa Malaysia there is a prevalence of Shari’ah Compliant listed companies (LCSC) that have, on average, a level of risk higher than the not Shari’ah Compliat listed companies (LCnotSC). There are some factors that drive both the leverage of the Shari’ah Compliant listed companies - that are linked to the respect of the financial ratio screen (debt screen, liquidity screen, interest screen and non-permissible income screen) and the beta, that are linked to the different level of debt and to the sensitivity of a share price to movement in the market price. In particular, we can assert that, for the sample analysed, LCSC collected using the application of the principles of Islamic finance, shows a higher level or risk, measured by Beta levered. More research is necessary to examine the potential effect on the risk as result of the principles used to divide the companies between Shari’ah Compliant and not Shari’ah Compliant. In particular, it may be interesting to understand why, contrary to the requirements of the traditional corporate finance - that postulate that an increase of leverage (D/E) implies a high level of risk (Beta levered) - the Shari’ah Compliant companies, while presenting a financial ratio below 33%, appear to be riskier of not-Shari’ah.One interesting research area is the extension of this analysis to other Countries and/or Financial Markets, implementing the use of statistical instruments in order to verify the significance of what observed in this exploratory study. Furthermore, these first results open new spaces for advanced research and comparative studies, in particular with reference to the cost of capital (equity and debt) and to the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) that represents the minimum acceptable hurdle rate of return within an investment decision.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML