-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2015; 4(5): 281-292

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20150405.06

An Empirical Investigation of the Debt Maturity of Italian Family Firms

Oscar Domenichelli

Department of Management, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Piazzale R. Martelli, Ancona, Italy

Correspondence to: Oscar Domenichelli, Department of Management, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Piazzale R. Martelli, Ancona, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study examines, through a dynamic panel data methodology (GMM-SYS) applied on a sample of 1,224 Italian family firms, whether and how the debt maturity structure of Italian family firms is determined by asset maturity, taxes, agency conflicts between managers and shareholders and between shareholders and creditors, liquidity risk, asymmetric information, the recent crisis, and the past dynamics of the debt maturity structure itself. Firstly, Italian family firms do not immediately adjust their maturity structure to its target and this adjustment is costly. There is no evidence of the maturity matching principle, nor of taxes influencing the debt maturity of Italian family firms. Conflicts of interests between managers and shareholders increase as Italian family firms get older, hence older Italian family firms use more long-term debt. Moreover, the scarce presence of conflicts of interest between shareholders and creditors causes long-term debt to augment, as it is used to properly exploit growth opportunities and thus, finance long-term investments. Both low-quality and high-quality Italian family-owned businesses tend to use short-term debt, since the former are screened out of the long-term debt market and the latter employ short-term debt to signal their quality when new positive information becomes available. Finally, lower asymmetric information increases the amount of long-term debt Italian family firms can get, whereas the crisis has had a negative impact on their debt maturity and this is linked to a reduced need for long-term debt to finance the permanent assets of Italian family firms. My empirical research represents an attempt to interpret the main determinants influencing the debt maturity structure of Italian family firms, by using an advanced econometric model which can better explain the financial behaviour of the firms being surveyed. Because the work deals with Italian family firms, no comparison based on country-specific aspects has been made among family firms belonging to different countries. Moreover, the absence of detailed yearly information on the ownership, board of directors, and managers prevented me from further enhancing the knowledge of the relationship between agency conflicts and debt maturity of Italian family firms. However, these two limitations may constitute further streams of future applied research.

Keywords: Debt maturity, Maturity matching, Taxation, Agency conflicts, Liquidity risk, Asymmetric information, Financial crisis

Cite this paper: Oscar Domenichelli, An Empirical Investigation of the Debt Maturity of Italian Family Firms, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 4 No. 5, 2015, pp. 281-292. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20150405.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is well-known among researchers that the publication of the seminal works of [1, 2] has generated an extensive theoretical and empirical literature on capital structure - that can be defined as the mix between debt and equity -, which has studied market imperfections, i.e. mainly taxes and bankruptcy costs [3], agency costs [4-6], and asymmetric information [7, 8]. The analysis of the debt maturity structure of firms is more recent, but it has nevertheless produced an ample body of specific literature which has essentially focused on its determinants, such as those related to maturity matching [9, 10], taxation [11-13], agency conflicts between managers and shareholders [14-16], agency conflicts between shareholders and creditors [6, 17], and asymmetric information [18-21]1. However, empirical research primarily concerns large companies in the United States [23, 24, 10, 14, 25, 26], Europe [27, 28], Latin America [29], Asia Pacific [30], and Australia [31]. Very few research studies have been conducted on small and medium-sized enterprises (for example: [32-34]) and even fewer papers have dealt with family firms (among others: [35, 36]).Moreover, to the best of my knowledge, no empirical research has specifically been carried out on the firm-level determinants of the debt maturity structure of Italian family firms; previous studies on debt maturity have mainly examined a sample of Italian companies, mostly unquoted [37], non-public Italian firms of small and medium size [38, 39] and Italian manufacturing firms with net sales of over one million euros and at least two employees [40]. Therefore, as further detailed later in this work, I assess direction and significance of the relationships existing between the lagged value over one period of the debt maturity, asset maturity, effective tax rate, firm age, growth opportunities, liquidity risk, information asymmetries, and crisis which are the independent variables, and debt maturity which represents the dependent variable. To this end, I examine a sample of 1,224 Italian family firms selected from AIDA (Italian Digital Database of Companies - the Italian provider of Bureau Van Dijk European Databases) and analysed over the period from 2004 to 2013. I employ a dynamic panel data model, through the use of the generalized method of moments system (GMM-SYS) estimator, by [41] and [42]. In particular, I make use of the two-step GMM-SYS estimator.In the present study I shed light on the debt maturity structure of Italian family firms by verifying the major determinants of it. Moreover, I extend the basic models of econometric analysis through the application of a dynamic panel data model, which takes into account a possible long-run optimal debt maturity for the firms surveyed and the related costs of being off-target versus the costs of adjustment towards the target itself.The main findings of my empirical research are the following. Firstly, Italian family firms face costly and non-instantaneous adjustments towards their target maturity structure. Neither the applicability of the maturity matching principle, nor the influence of taxation on the debt maturity of Italian family firms are highlighted in the study. There are indications of the presence of increased conflicts of interests between managers and shareholders as Italian family firms get older and this implies a larger use of long-term debt. Conflicts of interest between shareholders and creditors are scarce, as shareholders of family firms are mainly committed to guaranteeing the survival of the firm, preserving the family's reputation, keeping the business within the family, and reducing risk, thus enhancing firm value as a whole and not simply that of the shareholders themselves. Therefore, long-term debt can be increased to finance long-term growth opportunities. Both low-quality and high-quality Italian family-owned businesses tend to use short-term debt, since the former are screened out of the long-term debt market and the latter employ short-term debt to signal their quality when new positive information becomes available. Lower asymmetric information allows Italian family firms to obtain a greater amount of long-term debt. Finally, the crisis has had a negative effect on the debt maturity and this can be explained in terms of a lesser need for long-term debt to finance the fixed component of Italian family firms’ assets.The remainder of this article is organized as follows. In the next section I provide a review of the relevant literature and some testable hypotheses. I discuss methodology and empirical results in section three where I also make some comparisons with larger companies. Section four concludes my article.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. The Dependent Variable: Debt Maturity

- [27] point out that several definitions of short- and long-term debt are used in international literature. For some, a debt is considered long-term if it is payable after a year (e.g., [32]), whereas for others, this is the case if it is payable after three years [23]. [10] use weighted average maturity of liabilities, while [32] use two maturity specifications: (a) long-term debt payable after one year to total debt ratio and (b) weighted-average debt maturity. Following accounting conventions and as in [27], I define long-term debt as debt maturing in more than one year and debt maturity (DMA) as long-term debt divided by total debt.

2.2. The Lagged Dependent Variable

- Some authors (such as [43, 27, 44]) observe that firms may have long-run optimal debt maturity, so they need to trade off the costs of being off-target with the costs of adjustment towards the target. Therefore, [27] suggest the addition of the lagged dependent variable “debt maturity” as an explanatory variable, to test whether there is a target optimal debt maturity structure and, if it exists, the degree of divergence (convergence) from (to) the target level. They also explain that a significant, positive, and less than unit coefficient of lagged debt maturity variable would suggest that firms have a target optimal debt maturity structure they tend towards, while a greater than unit coefficient would imply that firms do not have any target ratio. Therefore, the lagged dependent variable is included, on the right-hand side of the equation shown in paragraph 3.1, to examine the presence of possible adjustment costs towards target debt maturity structure. The characteristics of the relationship between the debt maturity lagged one year (DMAt-1) and the debt maturity are left to empirical evidence.

2.3. Maturity Matching

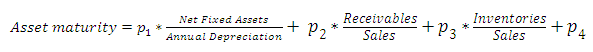

- [9] observes that firms match debt maturity to asset maturity since, on the one hand, debt maturity shorter than asset life means that firms do not have sufficient cash to reimburse or service their debts and, on the other, debt maturity longer than asset life may imply an insufficient cash flow to repay or service their debts as the assets no longer generate liquidity. [10] consider maturity matching a liquidity immunisation tool for firms, that is, a way of reducing the risk of not having enough cash flows to cover the payment associated with their debts. Several empirical investigations confirm the asset matching principle (among others: [45, 28, 46]). Therefore my first hypothesis is:H1: There is a positive relationship between asset maturity and debt maturity.I employ the following measure of asset maturity (AMA), which is calculated by [47], who slightly modify a previous version of the same indicator by [48]:

where p1, p2, p3 and p4 are, respectively, the proportion of net fixed assets, receivables, inventories and other current assets, excluding cash, to total assets.

where p1, p2, p3 and p4 are, respectively, the proportion of net fixed assets, receivables, inventories and other current assets, excluding cash, to total assets.2.4. Tax Hypothesis

- [49] argue that there are two alternative explanations on the influence of taxes on debt maturity. In fact, according to [50], borrowers could lengthen the maturity of their debts when the tax advantage of debt decreases, so that the remaining tax advantage of debt is not less than the amortized floatation costs. On the contrary, [51] assert that firms may increase the proportion of their long-term debt to maximize the benefit of a higher tax shield, which would also be exploitable for a longer period. This is due to an upward yield curve or/and the intrinsic structure of corporate debt [49]. Moreover, taxes may have no effect on debt maturity structure when both corporate and personal taxes are considered, and taxes may be negligible if debt maturity and leverage are chosen concurrently [12]. Accordingly, the empirical results are mixed and not always significant. For example, [10] and [52] find a negative relationship between tax rate and debt maturity, while [49] show a positive influence of tax rate on debt maturity. Furthermore, authors such as [23, 24, 43] document no evidence of a linkage between the two variables.For these reasons, the nature of the relationship between tax and debt maturity is an empirical issue and the effective tax rate (ETR), expressed as the ratio of tax paid to earnings before tax, is considered a valid tool to test the relationship just mentioned.

2.5. Agency Conflicts between Managers and Shareholders and Agency Conflicts between Shareholders and Creditors

- Some researchers [53-55] contend that family firms are less likely to be affected by agency conflicts between managers and shareholders and related costs [4], because of the recurrent blending of the functions of property, control and management [56] and their intra-familial altruistic linkages [57]. [58] refer to [59] and state that a family organisation enables a more effective control by managers and reduces divergences of interest between managers and shareholders, while [60] specifies that the reason why the agency costs of equity are insignificant in family firms has to do with their three dominant propensities, that is: parsimony in the use of the family’s personal wealth; personalism, deriving from the unification of ownership and control in the person of an owner–manager or family; and particularism, implying the use of both rational-calculative decision criteria and other “particularistic” criteria. Moreover, [61] describe a dynamic view of the agency costs of equity in family businesses. In fact, they contend that, in first-generation family firms, these agency costs are low for two main reasons. Firstly, there is a coincidence between ownership and management, as both are normally in the hands of the founder and his nuclear family. Secondly, the relationships within a nuclear family are closed, strong, and characterized by altruism, all of which enhance the firm’s value across successive generations. However, as time goes by and the successors take their place in the business, agency costs of equity tend to grow. In fact, a more dispersed ownership and management increases the likelihood of conflicts of interest and information asymmetries developing between owners and managers and it creates room for the opportunistic behaviour of managers. Since short-term debt gives lenders the flexibility to effectively monitor managers with minimum effort [15], reducing debt maturity is also an effective way to minimize the agency conflicts between owners and managers [62]. Therefore, selfish managers would prefer long-term debt to avoid the potential discipline of external monitoring [14]. As a consequence, when conflicts of interests between managers and shareholders are considerable, i.e., when a family firm is older, the former will prefer longer debt maturity. Hence, an additional hypothesis is:H2: Firm age is positively related to debt maturity.I utilize the number of years since the firm’s incorporation to study the linkage between its age (AGE) and debt maturity.If we look at the agency conflicts between shareholders and creditors, [4] assert that outstanding debt contracts may create incentives to over-invest, to the detriment of lenders. Instead, [6] studies the sub-optimal investment problem, whereby shareholders tend to pass up valuable investment opportunities when profits from investments will benefit only creditors, and argues that this can be avoided by issuing debt that matures before an investment opportunity can be carried out. [17] observe that the use of short-term bank debt may help resolve both the over-investment and the under-investment problems. These problems increase when firms have significant growth opportunities and, coherently with this position, [23] find that firms with more growth options in their investment opportunity sets employ a larger proportion of short-term debt. Consistent with the issue of agency problems of debt, [30] document a negative relationship between debt maturity and growth opportunities and [49] find that unconstrained firms with greater opportunities use less long-term debt. Moreover, as indicated by [63], long-term debt maturity structures significantly intensify the agency conflicts between creditors and shareholders, when the refinancing risk is high due to rollover losses [64, 65]. However, [66] argue that the divergence of interests between shareholders and creditors are less grave in family firms compared to non-family ones, because, as [67] describe, the family shareholders’ objectives of ensuring the long-term survival of the firm, preserving the family’s reputation, keeping the firm in the family, along with the undiversified character of their investment, tend to encourage family firms to maximize firm value as a whole, rather than simply focusing on shareholder value. Therefore, family firms with considerable investments in intangible fixed assets, and hence significant growth opportunities, can borrow long-term debt to adequately finance them. Hence, my next hypothesis is:H3: Growth opportunities are positively related to debt maturity.As a proxy for growth opportunities (GRO) the ratio of intangible fixed assets to total assets is calculated, as suggested by [68]. Given the fact that I only use book values, the widely-used market-to-book ratio cannot be employed in my empirical research.

2.6. Liquidity Risk and Asymmetric Information

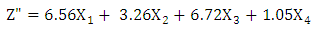

- Liquidity risk may be defined as the risk of not being able to repay debt, owing to the worsening in the financial or economic conditions of firms. This liquidity risk gives low-rated firms an incentive to extend the maturity of their debt to delay the probability of default, but these firms may not be able to do so, because low-quality firms may be screened out of the long-term debt market [24]. Nevertheless, there is another category of borrowers, i.e. the high-rated ones, that use short-term debt to benefit from the arrival of new favourable information, while middle-rated borrowers rely more heavily on long-term debt [19]. The presence of these two groups of enterprises, low- and high-rated ones in the first, and middle-rated ones in the second, implies that the debt maturity function is not monotonic. Therefore, the next hypothesis is:H4: Low- and high-rated family firms tend to have lower debt maturity compared to middle-rated firms.I make use of the Z”-Score [69, 70], as a measure for rating family firms and thus, as an inverse proxy of their liquidity risk (LIR). As explained by [71], I employ the Z”-Score [69, 70] - which was generated for manufacturing and non-manufacturing companies, as well as for companies in developing countries - because almost all the firms I include in the sample are non public. Moreover, the Z”-Score is more suitable for the Italian context compared to the Z’-Score [72]; the firms I have taken into consideration belong to several economic sectors (both manufacturing and non-manufacturing ones), and this model applied to non-US firms is much more robust than the other Altman Z- and Z’-Score models [70]. The Z”-Score [69, 70] is identified by the following formula:

where X1 is working capital/total assets, X2 is retained earnings/total assets, X3 is EBIT/total assets and X4 is book value equity/total liabilities.In particular, I exploit a dummy variable which takes the value of 1 for firms with a low or high Z”-Score, i.e., for low- and high-rated family firms, and 0 otherwise, i.e. for middle-rated family firms. Specifically, the whole range of variation of the Z”-Score for the family firms being studied, that is 85.94 – (-13.26) = 99.21, is divided by 3, that is 99.21/3 = 33.07, to generate three sub-intervals of equal width, with the following values: [-13.26, 19.80); [19.80, 52.87); [52.87; 85.94]. Then, I assign a value of one (1), to each observation, if the Z”-Score is in between [-13.26, 19.80) and [52.87; 85.94] and zero (0) if the Z”-Score is in between [19.80, 52.87).Monitoring is helpful in reducing adverse selection and avoiding some incentive problems related to the relationship between lenders and borrowers, and monitoring is facilitated by decreasing debt maturity. Therefore, when asymmetric information is lower there is less need to monitor borrowers and debt maturity can increase [39]. Empirical evidence suggests that firms with stronger information asymmetries employ more short-term debt [23] and that maturity is shorter for firms that are more opaque [73]. Hence, my further hypothesis is:H5: Information asymmetries are negatively related to debt maturity.Here I draw on the ratio of tangible fixed assets to total assets to determine an inverse proxy of information asymmetries (INA), as suggested by [39], for example.

where X1 is working capital/total assets, X2 is retained earnings/total assets, X3 is EBIT/total assets and X4 is book value equity/total liabilities.In particular, I exploit a dummy variable which takes the value of 1 for firms with a low or high Z”-Score, i.e., for low- and high-rated family firms, and 0 otherwise, i.e. for middle-rated family firms. Specifically, the whole range of variation of the Z”-Score for the family firms being studied, that is 85.94 – (-13.26) = 99.21, is divided by 3, that is 99.21/3 = 33.07, to generate three sub-intervals of equal width, with the following values: [-13.26, 19.80); [19.80, 52.87); [52.87; 85.94]. Then, I assign a value of one (1), to each observation, if the Z”-Score is in between [-13.26, 19.80) and [52.87; 85.94] and zero (0) if the Z”-Score is in between [19.80, 52.87).Monitoring is helpful in reducing adverse selection and avoiding some incentive problems related to the relationship between lenders and borrowers, and monitoring is facilitated by decreasing debt maturity. Therefore, when asymmetric information is lower there is less need to monitor borrowers and debt maturity can increase [39]. Empirical evidence suggests that firms with stronger information asymmetries employ more short-term debt [23] and that maturity is shorter for firms that are more opaque [73]. Hence, my further hypothesis is:H5: Information asymmetries are negatively related to debt maturity.Here I draw on the ratio of tangible fixed assets to total assets to determine an inverse proxy of information asymmetries (INA), as suggested by [39], for example.2.7. The Effects of the Financial Crisis

- The financial crisis that followed the subprime mortgage market problems in the United States caused a global effect all over the world and later added to the sovereign debt crisis of the so-called “Eurozone” of the European Union.Over this time span, approximately from the latter part of 2007 to the present, firms have experienced a substantial worsening in their ability to obtain credit from banks. [74] observe that finance literature has investigated the underlying causes of this phenomenon, producing three main interpretations. According to some, the situation essentially depends on the restriction of the supply of bank financing [75-78]; according to others, instead, it is mainly a contraction in the demand for credit by firms [79, 80]; finally, there are those who claim that this issue should be viewed as the product of a simultaneous reduction in both credit supply and credit demand [81, 82]. However, [83] stress that much of the existing research literature concentrates mainly on publicly listed large firms (among others: [84, 85, 86]). Therefore, less attention has been devoted to other kinds of firms, such as family ones.From an Italian viewpoint, the financial crisis badly affected non-financial Italian firms in terms of credit flow. In fact, over the period that went from the second half of 2008 through the end of 2009, credit to these types of companies initially grew at progressively lower rates and later, the variation dipped into negative figures [87, 88]. In light of that, it is apt to state that the credit situation experienced by these firms, especially the small and medium-sized ones, was the result of two combined forces, although some scholars lean more towards one or the other explanation, as previously illustrated. On the one hand, the reduction in credit concessions from banks could have severely limited access to external sources of bank debt, especially for "Eurozone" firms operating in a bank-oriented financial system. This consequence was particularly serious for non-financial enterprises, especially the smaller ones, in countries like Italy [89]. On the other hand, the drop in company investments, tied to a strong feeling of uncertainty regarding domestic and foreign demand, could have caused a fall in the number of requests for financing coming from Italian companies.2 However, 2010 saw an improvement in the ability of Italian firms to raise capital. Nonetheless, in the following years there was first a shrinking of credit growth followed by a sharp decline, due to the sovereign debt crisis [87, 88] which erupted in late 2009 and which also affected Italy. Again, if we specifically look at this country and at the period of the sovereign debt crisis, the increased spread between Italian and German public debt bonds resulted in the credit market being effected two ways. On one side, there was a worsening in both the quality and quantity of the demand for credit, owing to the economic impact of fiscal tightening. On the other, the cost of bank financing increased because of the competition banks felt from the State in accessing capital [90] and this, in turn, made it more costly and thus difficult for firms to finance their investments.As far as the purpose of this work is concerned, I am specifically interested in understanding the impact of the financial crisis on the debt maturity structure of Italian family firms. Previous research indicates that, during the crisis, firms had an incentive to switch to longer-term debt maturity to avoid financial distress [91], generated by shorter debt maturities in a context of negative perceptions about the evolution of their own future business, and to postpone possible problems in obtaining credit from banks, at least at an affordable rate of interest. Therefore, my last hypothesis is:H6: The financial crisis has caused firms to increase debt maturity.To test it, I employ a dummy variable (CRI) which takes the value of 1 for the crisis years (2008/2013) and 0 for the non-crisis years (2004/2007).

3. Methodology and Empirical Results

3.1. Sample and Model Characteristics

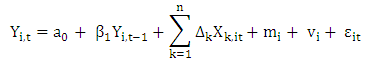

- My research sample is composed of family firms. There is still not a common, widespread definition of family firm in the extant literature, but attempts have been made to systematize existing family firm definitions (see [93]). The point is that what characterizes a family business is the significant impact of family on it, but the nature and extent of the family involvement are variable [94]. A few authors use multiple operational definitions of family firms (for example, [95, 96]), while a few others employ scales to take into account different kinds of family participation [97] or employ family firm typologies [98]. Furthermore, according to some, a single definition of family firm could even be ambiguous, as this would not be able to take into account fundamental distinctions existing in various legal and institutional frameworks [60, 99]. As further described below, for the purpose of this work I apply the following definition of a family firm: a firm in which at least 50% of the equity, representing a significant proportion, is held jointly by persons or families and which has at least 50 employees. The adopted definition is similar to that of [100] who define family firms as businesses with a shareholder (single or family) owning more than 50% and having between 50 and 250 employees. I drew all the sample data from AIDA, which is the Italian provider of Bureau Van Dijk European Databases and contains comprehensive financial and ownership information concerning Italian companies. The initial sample comprised all active Italian family companies included in the database with one or more named individuals or families jointly owning at least 50% of the equity and having at least 50 employees for all the years of the survey, which amounts to 2,513 firms. I chose family businesses of this size in order to obtain more reliable financial information and make the research easier to compare, as most of the studies on family firms deal with relatively large companies [100]. This also allowed me to take into account the issue of size variability. However, to enter the final sample, useful data had to be available for all the variables, considered in the regression model presented below, for the period 2004-2013. In fact, as emphasised by [101], a dynamic model of estimation requires at least three consecutive annual observations and at least five consecutive observations for diagnostics to be robust. Therefore, at the end of the preliminary work, I excluded several companies from the initial sample either because of some unavailable data or negative effective tax rates for one or more years or some ratios having denominators equal to zero. So, the final sample includes 1,224 family firms. All the values of the variables are book values.Similarly to [28], I adopt the following model to examine the empirical determinants of debt maturity, through a panel data methodology:

where Yi,t is a measure of debt maturity, i.e. long-term debt over total debt, for firm i at year t; a0 is the constant; Yi,t-1 is the lagged value over one period of debt maturity; X is a group of k (k = 1, ..., 7) independent variables, as defined in the previous section; β1 and Δk are unknown parameters to be estimated; mi are time-invariant unobservable firm-specific effects, such as reputation, capital intensity and attributes of managers, which vary across firms but are assumed to be fixed for a given firm through time; vi represents firm-invariant time-specific effects, e.g. interest rates and inflation, which are common to all firms but can change over time; εi,t is a disturbance term which is assumed to be serially uncorrelated with mean zero.As summarized by [29], [102] lists three advantages of panel data methodology. Firstly, it generates larger datasets with more variability and less collinearity among explanatory variables. Secondly, it enables the investigation of issues that cannot be simply addressed by cross-section or time series datasets. Thirdly, it provides a means of reducing the missing variable problem. [29] also observes that [103] adds further benefits of panel data analysis, that is, the usually higher accuracy of micro-unit data compared to aggregate data and the possibility of taking into account the dynamics of adjustment of a specific phenomenon through time.Although estimation of panel data models can be done by employing fixed or random effects models, in the presence of a lagged dependent variable amongst the explanatory variables these models may give biased and inconsistent estimators, since the error term may be correlated with the lagged dependent variable. To deal with this problem, instrumental variables can be exploited. The use of instrumental variables has the additional advantage of solving further problems of static models, that is, the simultaneity bias between the measure of the dependent variable and the explanatory variables, and measurement error issue [104]. [27] cite [105] who propose an instrumental variables (IV) technique whose estimators, though, might not be efficient as they do not use all the available moment conditions and do not account for the differenced structure of the error term. Furthermore, [106] highlights that [107] alternatively suggest employing the GMM specification of the first differences (GMM-DIF) - by instrumenting the dependent variable and the predetermined variables with lagged levels, and instrumenting the strictly exogenous variables with differences - as this enables researchers to deal with endogeneity and simultaneity biases. However, as noted by [27], [42] document that the extended GMM (GMM-SYS) estimator of [41] - who propose the use of both instruments in first differences for equations in levels and instruments in levels for equations in first differences - has important efficiency gains compared to GMM-DIF, for example, when the empirical study is characterized by short sample periods and persistent data. In particular, I apply the two-step GMM-SYS estimator because those estimates are deemed to be more efficient than the first-step ones [27] and I consider a few statistical tests to ascertain the consistency of the two-step GMM-SYS estimator. Firstly, I run the [107] tests on autocorrelation to find out if the error term exhibits no serial autocorrelation. Secondly, I use the [108] statistics to test the overall validity of the instruments. Finally, I conduct the Wald test for the joint significance of the estimated coefficients.

where Yi,t is a measure of debt maturity, i.e. long-term debt over total debt, for firm i at year t; a0 is the constant; Yi,t-1 is the lagged value over one period of debt maturity; X is a group of k (k = 1, ..., 7) independent variables, as defined in the previous section; β1 and Δk are unknown parameters to be estimated; mi are time-invariant unobservable firm-specific effects, such as reputation, capital intensity and attributes of managers, which vary across firms but are assumed to be fixed for a given firm through time; vi represents firm-invariant time-specific effects, e.g. interest rates and inflation, which are common to all firms but can change over time; εi,t is a disturbance term which is assumed to be serially uncorrelated with mean zero.As summarized by [29], [102] lists three advantages of panel data methodology. Firstly, it generates larger datasets with more variability and less collinearity among explanatory variables. Secondly, it enables the investigation of issues that cannot be simply addressed by cross-section or time series datasets. Thirdly, it provides a means of reducing the missing variable problem. [29] also observes that [103] adds further benefits of panel data analysis, that is, the usually higher accuracy of micro-unit data compared to aggregate data and the possibility of taking into account the dynamics of adjustment of a specific phenomenon through time.Although estimation of panel data models can be done by employing fixed or random effects models, in the presence of a lagged dependent variable amongst the explanatory variables these models may give biased and inconsistent estimators, since the error term may be correlated with the lagged dependent variable. To deal with this problem, instrumental variables can be exploited. The use of instrumental variables has the additional advantage of solving further problems of static models, that is, the simultaneity bias between the measure of the dependent variable and the explanatory variables, and measurement error issue [104]. [27] cite [105] who propose an instrumental variables (IV) technique whose estimators, though, might not be efficient as they do not use all the available moment conditions and do not account for the differenced structure of the error term. Furthermore, [106] highlights that [107] alternatively suggest employing the GMM specification of the first differences (GMM-DIF) - by instrumenting the dependent variable and the predetermined variables with lagged levels, and instrumenting the strictly exogenous variables with differences - as this enables researchers to deal with endogeneity and simultaneity biases. However, as noted by [27], [42] document that the extended GMM (GMM-SYS) estimator of [41] - who propose the use of both instruments in first differences for equations in levels and instruments in levels for equations in first differences - has important efficiency gains compared to GMM-DIF, for example, when the empirical study is characterized by short sample periods and persistent data. In particular, I apply the two-step GMM-SYS estimator because those estimates are deemed to be more efficient than the first-step ones [27] and I consider a few statistical tests to ascertain the consistency of the two-step GMM-SYS estimator. Firstly, I run the [107] tests on autocorrelation to find out if the error term exhibits no serial autocorrelation. Secondly, I use the [108] statistics to test the overall validity of the instruments. Finally, I conduct the Wald test for the joint significance of the estimated coefficients.3.2. Descriptive Statistics

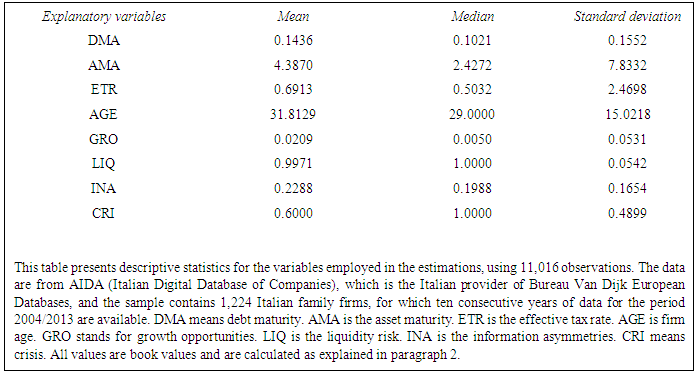

- I discuss below the main results shown in Table 1. On average, the debt maturity (DMA) is 0.1436 and this means a small use of long-term debt, especially when compared with the mean asset maturity (AMA) (4.3870), even if the latter variable is not expressed in the same kind of measure. Among the variables which are not dummies, the firm age (AGE) and the asset maturity (AMA) are characterized by the greatest variability (their standard deviations are greater than 7), while the standard deviations of the growth opportunities (GRO) and the debt maturity (DMA) indicate the lowest variability (their values are less than 0.16). The mean value of the effective tax rate (ETR) is 0.6913. That points to the heavy weight, on average, of the surveyed firms’ tax burden. Moreover, this finding can be seen as quite surprising. In Italy however, unlike the situation in other European countries, a regional tax is levied on productive activities; it is the IRAP (Imposta regionale sulle attività produttive), which is calculated not on earnings before tax but on the difference between operating revenues and a few costs, so the IRAP is paid on costs such as interest concerning leasing and some labour costs too. As a consequence, the IRAP is also payable in the event of a loss being reported and this justifies the high, mean effective tax rate. It is worth noting that, however, the rules concerning the IRAP have recently changed. The mean firm age (AGE) is quite high (greater than 31) and this is partly caused by the choice of a 10-year period of analysis, which obviously excludes the youngest enterprises. The mean values of the growth opportunities (GRO) (0.0209) and the information asymmetries (INA) (0.2288) lead me to point out that while Italian family firms have a low tendency to invest in intangible fixed assets, the employ of capital in assets, which are tangible, seems to represent a more important strategic choice for these enterprises.

|

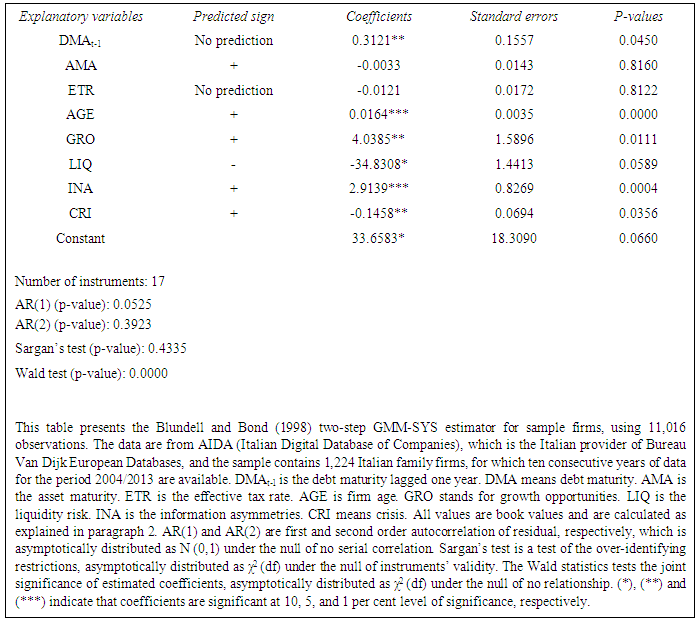

3.3. Regression Analysis

- The parameter estimates as well as some statistical tests are displayed in Table 2. The [107] test for first order autocorrelation, AR(1), rejects the hypothesis of no autocorrelation at level 0.1 of significance, while, more importantly, the [107] test for second order autocorrelation, AR(2), does not reject the hypothesis of no autocorrelation. Furthermore, the [108] test of the over-identifying restrictions confirms the validity of the instrumental variables being used. Finally, the Wald test indicates the joint significance of the estimated coefficients.On the whole, the results confirm the hypotheses I put forward, albeit with different significance and except for two relationships. My findings are presented in Table 2 and thoroughly commented below.

|

4. Conclusions

- In this work, the use of a two-step GMM-SYS model aims to provide an explanation of the empirical determinants of the debt maturity choice of Italian family firms.Specifically, I assess direction and significance of the relationships existing between the lagged value over one period of the debt maturity, asset maturity, effective tax rate, firm age, growth opportunities, liquidity risk, information asymmetries, and crisis which are the independent variables, and debt maturity which represents the dependent variable.Firstly, the results show that the debt maturity of Italian family firms heavily depends on its past dynamics, and that these firms are not able to reach their target maturity structure instantaneously and with low costs. Since the asset matching principle is neither observed nor rejected in my empirical work, one possible explanation is that the firms being studied tend to rely on the rolling over of short-term debt, that is to say that short-term debt basically becomes long-term, so that the long term-debt measure I employ cannot actually prove the presence or absence of the principle mentioned above. Taxes do not represent a determining factor in the debt maturity of Italian family firms, while the positive and significant relationship between the debt maturity and the firm age supports the presence of increased conflicts of interests between managers and shareholders when Italian family firms get older, with self-interested managers preferring longer debt maturity to reduce the burden of monitoring by lenders. My work also substantially documents the scarce presence of conflicts of interest between shareholders and creditors and this is due to the fact that the shareholders of family firms are mostly committed to ensuring the survival of the firm, preserving the family's reputation, keeping the business within the family, and reducing risk, thus enhancing firm value as a whole and not only that of the shareholders themselves. Therefore, Italian family firms largely employ long-term debt to adequately finance long-term investment prospects, thus exploiting growth opportunities. Furthermore, there is evidence that low-quality Italian family enterprises tend to be excluded from the long-term debt market, while high-quality Italian family businesses use short-term debt to emphasize their quality when new positive information is available and, in fact, both types of firms tend to employ more short-term debt. As expected, the presence of lower asymmetric information increases the amount of long-term debt Italian family firms can use, since there is less need for creditors to monitor borrowers. Finally, contrary to my hypothesis, the crisis has had a negative impact on debt maturity and this may have been caused by a decline in investments, especially between 2008 and 2009 as shown by [92]. In fact, this decline has reduced the need for long-term debt to finance the fixed component of the assets of Italian family firms.I believe that a major contribution of this work is that it develops the research on the debt maturity structure of Italian family firms by examining the main determinants of it. In addition, I extend the basic models of econometric analysis through the application of a dynamic panel data model, which takes into account a possible long-run optimal debt maturity structure for the firms surveyed and the related costs of being off-target versus the costs of adjustment towards the target itself.I put forward the two main implications of my study. Firstly, as seen, conflicts of interest between shareholders and managers become significant when Italian family firms get older. These may be magnified by the presence of family members who are appointed managers through nepotism rather than merit and who are thus of lesser quality than potential hired professionals, as observed by [66]. Consequently, this should push company founders to hire, at least some, professional managers to decrease the agency costs of family management and improve firm value. Secondly, there is evidence that Italian family firms have reduced the amount of long-term debt owing to a decline in fixed investments caused by the crisis. Hence, Italian policy makers should adopt policy measures aimed at stimulating a demand these firms can serve, for instance through reduced labour costs and personal tax reductions.One limitation of the study concerns the fact that it is focused on Italian family firms, therefore the effects of country-specific factors on the debt maturity structure of family firms belonging to different countries were not examined. Another limitation refers to the lack of availability of yearly information regarding the specific characteristics of shareholders, board directors and managers, which could have allowed me to investigate more in depth the linkage between agency problems (for example, between controlling shareholders and non-controlling shareholders, or between shareholders and managers when heirs are appointed managers or successors become CEOs) and the debt maturity of Italian family firms.As a result, researchers could further investigate if and how country-specific factors – such as financial systems and institutional traditions, as highlighted for example by [27] for non-financial firms traded on the stock exchanges of France, Germany and the UK - determine the debt maturity choice of family firms around the world. Moreover, further research studies could try to assess the effect of ownership and management features on the debt maturity decisions of Italian family-owned businesses.

Notes

- 1. For a thorough survey of the theoretical and empirical studies on the maturity structure of corporate debt, see [22].2. Investments by Italian firms went from a figure close to 120 in 2007, to a figure just barely above 100 in 2010 (index values, with 2005 equal to 100). Between 2008 and 2009 there was a tendency towards improvement in Italian firms’ capability to self-finance their investment expenditures (expressed by the ratio between self-financing and investment), but it is in direct proportion to the fall in investments themselves [92].

References

| [1] | Modigliani, F. and Miller, M. H. (1958). The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment, American Economic Review, 48, 3, 261-297. |

| [2] | Modigliani, F. and Miller, M. H. (1963). Corporate Income Taxes and the Cost of Capital: a Correction, American Economic Review, 53, 3, 443-453. |

| [3] | Kraus, A. and Litzenberger, R. H. (1973). A State-preference Model of Optimal Financial Leverage, Journal of Finance, 28, 4, 911–922. |

| [4] | Jensen, M. C. and Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure, Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 4, 305-360. |

| [5] | Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers, American Economic Review, 76, 2, 323–329. |

| [6] | Myers, S. C. (1977). Determinants of corporate borrowing, Journal of Financial Economics, 5, 147–175. |

| [7] | Myers, S. C. (1984). The Capital Structure Puzzle, Journal of Finance, 39, 3, 575-592. |

| [8] | Myers, S. C. and Majluf N. S. (1984). Corporate Financing and Investment Decisions When Firms Have Information That Investors Do Not Have, Journal of Financial Economics, 13, 2, 187-221. |

| [9] | Morris, J. R. (1976). On Corporate Debt Maturity Strategies, Journal of Finance, 31, 1, 29–37. |

| [10] | Stohs, M. H and Mauer, D. C. (1996). The Determinants of Corporate Debt Maturity Structure, Journal of Business, 69, 3, 279-312. |

| [11] | Brick, I. E. and Ravid, S. A. (1985). On the Relevance of Debt Maturity Structure, Journal of Finance, 40, 6, 1423-1437. |

| [12] | Lewis, C. M. (1990). A Multiperiod Theory of Corporate Financial Policy under taxation, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 25, 1, 25-43. |

| [13] | Brick, I. E., and Ravid, S. A. (1991). Interest rate uncertainty and the optimal debt maturity structure, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 26, 1, 63-81. |

| [14] | Datta, S., Iskandar-Datta, M. and Raman, K. (2005). Managerial Stock Ownership and the Maturity Structure of Corporate Debt, Journal of Finance, 60, 5, 2333-2350. |

| [15] | Rajan, R. and Winton, A. (1995). Covenants and collateral as incentives to monitor, Journal of Finance, 50, 4, 1113-1146. |

| [16] | Jiraporn, P. and Kitsabunnarat, P. (2007). Debt maturity structure, shareholder rights, and corporate governance, Working Paper, Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=999265. |

| [17] | Barnea, A., Haugen, R. A. and Senbet, L. W. (1980). A rationale for debt maturity structure and call provisions in the agency theory framework, Journal of Finance, 35, 5, 1223–1234. |

| [18] | Flannery, M. J. (1986). Asymmetric Information and Risky Debt Maturity Choice, Journal of Finance, 41, 1, 19-37. |

| [19] | Diamond, D. W. (1991). Debt maturity structure and liquidity risk, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 3, 709-737. |

| [20] | Kale, J. R. and Noe, T. H. (1990). Risky debt maturity choice in a sequential equilibrium, Journal of Financial Research, 13, 2, 155-166. |

| [21] | Goswami, G., Noe, T. H., and Rebello M. (1995). Cash flow correlation, debt maturity choice, and symmetric information, Advances in Financial Planning and Forecasting, 6, 109-134. |

| [22] | Ravid, S. A. (1996). Debt Maturity-A survey, Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments, 5, 3, 1-69. |

| [23] | Barclay, M. J. and Smith, C. W. Jr (1995). The Maturity Structure of Corporate Debt”, Journal of Finance, 50, 2, 609-631. |

| [24] | Guedes, J. and Opler, T. (1996). The determinants of the maturity of corporate debt issues, Journal of Finance, 51, 5, 1809-1833. |

| [25] | Billett, M. T., King, T.-H. D. and Mauer, D. C. (2007). Growth Opportunities and the Choice of Leverage, Debt Maturity, and Covenants, Journal of Finance, 62, 2, 697–730. |

| [26] | Brockman, P., Martin, X. and Unlu E. (2010). Executive Compensation and the Maturity Structure of Corporate Debt, Journal of Finance, 65, 3, 1123-1161. |

| [27] | Antoniou, A., Guney, Y. and Paudyal, K. (2006). The Determinants of Debt Maturity Structure: Evidence from France, Germany and the UK, European Financial Management, 12, 2, 161–194. |

| [28] | Ozkan, A. (2002). The determinants of corporate debt maturity: evidence from UK firms, Applied Financial Economics, 12, 1, 19-24. |

| [29] | Terra, P. R. S. (2011). Determinants of corporate debt maturity in Latin America, European Business Review, 23, 1, 45-70. |

| [30] | Chen, S.-S., Ho, K. W. and Yeo, G. H. H. (1999). The Determinants of Debt Maturity: the Case of Bank Financing in Singapore, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 12, 4, 341-350. |

| [31] | Alcock, J., Finn, F. and Tan, K. J. K. (2012). The Determinants of debt maturity in Australian firms, Accounting & Finance, 52, 2, 313-341. |

| [32] | Scherr, F. and Hulburt, H. M. (2001). The Debt Maturity Structure of Small Firms, Financial Management, 30, 1, 85-111. |

| [33] | García-Teruel, P. J. and Martínez-Solano, P. (2007). Short-term debt in Spanish SMEs, International Small Business Journal, 25, 6, 579-602. |

| [34] | López-Gracia, J., Mestre-Barberá, R. (2011). Tax effect on Spanish SME optimum debt maturity structure, Journal of Business Research, 64, 6, 649-655. |

| [35] | Shyu, Y-W. and Lee, C. I. (2009). Excess Control Rights and Debt Maturity Structure in Family-Controlled Firms, Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17, 5, 611-628. |

| [36] | Chen, T.-Y., Dasgupta, S. and Yu, Y. (2014). Transparency and Financing Choices of Family Firms, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 49, 2, 381-408. |

| [37] | Schiantarelli, F. and Sembenelli, A. (1997). The Maturity Structure of Debt, The World Bank, Policy Research Department, Policy Research, Working Paper 1699, Electronic copy available at: http://web.econ.unito.it/sembenelli/debt_structure.pdf. |

| [38] | Magri, S. (2006). Debt maturity of Italian firms, Banca D’Italia, Temi di discussione del Servizio Studi, Number 574. |

| [39] | Magri, S. (2010). Debt Maturity Choice of Nonpublic Italian firms, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 42, 2-3, 443-463. |

| [40] | Lamieri, M. (2009). The debt maturity structure of Italian firms, Working Paper, Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1373752. |

| [41] | Arellano, M., and Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental-variable estimation of error-components models, Journal of Econometrics, 68, 1, 29-52. |

| [42] | Blundell, R. W. and Bond, S. R. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models, Journal of Econometrics, 87, 1, 115-143. |

| [43] | Ozkan, A. (2000). An empirical analysis of corporate debt maturity structure, European Financial Management, 6, 2, 197-212. |

| [44] | Kirch, G. and Terra P. R. S. (2012). Determinants of corporate debt maturity in South America: Do institutional quality and financial development matter?, Journal of Corporate Finance, 18, 4, 980-993. |

| [45] | Graham, J. and Harvey, C. (2001). The Theory and Practice of Corporate Finance: Evidence from the Field, Journal of Financial Economics, 60, 187-243. |

| [46] | Heyman, D., Deloof, M. and Ooghe, H. (2008). The Financial Structure of Private Held Belgian Firms, Small Business Economics, 30, 3, 301-313. |

| [47] | García-Teruel, P. J. and Martínez-Solano, P. (2010). Ownership structure and debt maturity: new evidence from Spain, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 35, 4, 473-491. |

| [48] | Jun, S-G. and Jen, F. C. (2003). Trade-off Model of Debt Maturity Structure, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 20, 5-34. |

| [49] | Stephan, A., Talavera, O. and Tsapin, A. (2011). Corporate debt maturity choice in emerging financial markets, The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 51, 2, 141-151. |

| [50] | Kane, A., Marcus, A. J. and McDonald R. L. (1985). Debt Policy and the Rate of Return Premium to Leverage, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 20, 4, 479-499. |

| [51] | Newberry, K. J. and Novack, G. F. (1999). The effect of taxes on corporate debt maturity decisions: An analysis of public and private bond offerings, Journal of the American Taxation Association, 21, 2, 1-16. |

| [52] | Thottekat, V. and Vij M. (2013). How tax hypothesis determines debt maturity in Indian corporate sector, Journal of Business and Finance, 1, 3, 112-125. |

| [53] | Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of social interaction. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 1063–1093. |

| [54] | Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: an assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14, 57–74. |

| [55] | Daily, C. M. and Dollinger, M. J. (1992). An empirical examination of ownership structure in family and professionally-managed firms. Family Business Review, 5, 117–136. |

| [56] | Hill, C. W. and Snell, S. A. (1989). Effects of ownership structure and control on corporate productivity. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 25–46. |

| [57] | Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H. and Litz, R. (2004). Comparing the agency costs of family and non-family firms: conceptual issues and exploratory evidence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28, 335–54. |

| [58] | Allouche, J., Amann, B., Jaussaud, J. and Kurashina, T. (2008). The Impact of Family Control on the Performance and Financial Characteristics of Family Versus Nonfamily Businesses in Japan: A Matched-Pair Investigation, Family Business Review, 21, 4, 315-329. |

| [59] | Fama, E. F. and Jensen, M. C. (1983). Agency Problems and Residual Claims, Journal of Law and Economics, 26, 2, 327-349. |

| [60] | Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29, 3, 249-265. |

| [61] | Blanco-Mazagatos, V., De Quevedo-Puente, E., and Castrillo, L. A. (2007). The trade-off between financial resources and agency costs in the family business: an exploratory study, Family Business Review, 20, 3, 199–213. |

| [62] | Stulz, R. (2000). Does financial structure matter for economic growth? A corporate finance perspective, Working Paper, Ohio State University, Electronic copy available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.18.9116&rep=rep1&type=pdf. |

| [63] | Pour, E. K. and Lasfer, M. (2014). Taxes, Governance, and Debt Maturity Structure, Working Paper, Electronic copy available at: http://www.efmaefm.org. |

| [64] | Almeida, H., Campello, M., Laranjeira, B. and Weisbenner, S. (2011). Corporate debt maturity and the real effect of the 2007 credit crisis, Critical Finance Review, 1(1), 3-58. |

| [65] | Li, B. (2012). Refinancing Risk, Managerial Risk Shifting, and Debt Covenants: An Empirical Analysis, Working Paper, Queen's University, Electronic copy available at: http://cn.ckgsb.com/Userfiles. |

| [66] | Villalonga, M., Amit, R., Trujillo, M.-A. and Guzmán, A. (2014). Governance of Family Firms, Working Paper. |

| [67] | Anderson, R. C., Mansi, S. A., Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding family ownership and the agency cost of debt. Journal of Financial Economics, 68, 263-285. |

| [68] | Mateus, C. and Terra, P. (2013). Leverage and the Maturity Structure of Debt in Emerging Markets, Journal of Mathematical Finance, 3, 46-59. |

| [69] | Altman E. I., Hartzell, J. and Peck, M. (1995). Emerging Markets Corporate Bonds: A Scoring System, Salomon Brothers Inc. New York, and in Levich, R. and Mei, J. P., The Future of Emerging Market Flaws, Kluwer Publishing, revisited in Altman, E. I., and Hotchkiss, E. (2006), Corporate Financial Distress & Bankruptcy, J. Wiley & Sons, New York. |

| [70] | Altman, E. I. and Hotchkiss, E. (2006). Corporate Financial Distress & Bankruptcy, 3rd edition, Hoboken, J. Wiley & Sons, New York. |

| [71] | Altman, E. I., Danovi, A. and Falini, A. (2013). Z-Score Models’ Application to Italian Companies Subject to Extraordinary Administration, Journal of Applied Finance, 23(1), 128-137. |

| [72] | Altman, E. I., (1983). Corporate Financial Distress, New York, Wiley InterScience. |

| [73] | Ortiz-Molina, H. and Penas, M. F. (2008). Lending to small businesses: the role of loan maturity in addressing information problems, Small Business Economics, 30, 361-383. |

| [74] | Soana, M. G., Verga, G. and Gandolfi, G. (2013). Are Private SMEs Financially Constrained During the Crisis? Evidence from the Italian Market, Working paper, September 9. Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2322808 |

| [75] | Albertazzi, U. and Marchetti, D. J. (2010). Credit supply, flight to quality and evergreening: an analysis of bank-firm relationships after Lehman, Bank of Italy, Working papers, 756, 1-51. |

| [76] | Puri, M., Rocholl, J. and Steen, S. (2011). Global retail lending in the aftermath of the US financial crisis: distinguishing between supply and demand effects, Journal of Financial Economics, 100, 3, 556-578. |

| [77] | Jimenéz, G., Ogena, S., Peydró, J. L. and Saurina, J. (2012). Credit supply versus demand: bank and firm balance sheet channels in good and bad times, European Banking Center, Discussion Paper, December 2011, 1-33. |

| [78] | Iyer R., Lopes S., Peydro J. and Schoar A. (2013). Interbank liquidity crunch and the firm credit crunch: evidence from the 2007-2009 crisis, Review of Financial Studies, doi: 10.1093/rfs/hht056, first published online: October 7, 2013, 1-26. |

| [79] | Kremp, E. and Sevestre, P. (2012). Did the crisis induce credit rationing for French SMEs?, Banque de France, Working paper n. 405, 1-44. |

| [80] | Rottmann, H. and Wollmershäuser, T. (2013). A micro data approach to the identification of credit crunches, Applied Economics, 45, 17, 2423-2441. |

| [81] | Popov, A. and Udell, G. F. (2010). Cross-border banking and the international transmission of financial distress during the crisis of 2007-2008, European Central Bank, Working paper n. 1203, pp. 1-49. |

| [82] | Presbitero, A. F., Udell, G. F. and Zazzaro, A. (2012), The home bias and the credit crunch: a regional perspective, MOFir, Working paper n. 60, pp. 1-32. |

| [83] | Akbar, S., Rehman, S. u. and Ormrod, P. (2013). The impact of recent financial shocks on the financing and investment policies of UK private firms, International Review of Financial Analysis, 26, 59-70. |

| [84] | Allen, F. and Carletti, E. (2008). The liquidity in financial crises. Working paper. Available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1268367. |

| [85] | Duchin, R., Ozbas, O. and Sensoy, B. (2010). Costly external finance, corporate investment, and the subprime mortgage credit crisis, Journal of Financial Economics, 97, 418–435. |

| [86] | Tong, H. and Wei, S.-J. (2008). Real effects of the subprime mortgage crisis: is It a demand or a finance shock? Working paper n. 14205. Available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w14205. |

| [87] | Banca d’Italia (2011), Eurosistema, Rapporto sulla stabilità finanziaria, 2, novembre, 1-67. |

| [88] | Banca d’Italia (2013a), Eurosistema, Rapporto sulla stabilità finanziaria, 6, novembre, 1-52. |

| [89] | Gualandri, E. and Venturelli, V. (2013). The financing of Italian firms and the credit crunch: findings and exit strategies, Cefin, Working paper n. 41, October, pp. 1-26. |

| [90] | Alessandrini, P., Papi, L., Presbitero, A. F. and Zazzaro, A. (2013). Crisi finanziaria globale, crisi finanziaria e crisi bancaria: l’Italia e il confronto europeo, MOFir, Working paper n. 87, settembre, 1-32. |

| [91] | Willsey, A. E. and Siregar, D. (2012). The Effects Of The 2008-2009 Financial Crisis On U.S. Corporate Debt Structure, New York Economic Review, 43, 16-32. |

| [92] | Banca d’Italia (2013b), Eurosistema, Relazione annuale - anno 2012, Roma, 31 maggio, pp. 1-327. |

| [93] | Harms, H. (2014). Review of Family Business Definitions: Cluster Approach and Implications of Heterogeneous Application for Family Business Research, International Journal of Financial Studies, 2, 280-314. |

| [94] | Sharma, P. (2004). An Overview of the Field of Family Business Studies: Current Status and Directions for the Future, Family Business Review, 17, 1, 1-36. |

| [95] | Astrachan, J. H. and Shanker, M. C. (2003). Family businesses’ contribution to the U.S. economy: a closer look, Family Business Review, 16, 3, 211–19. |

| [96] | Westhead, P., and Cowling, M. (1998). Family firm research: the need for a methodology rethink, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 1, 31–56. |

| [97] | Astrachan, J. H., Klien, S. B. and Smyrnios, K. X. (2002). The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem, Family Business Review, 15, 1, 45–58. |

| [98] | Sharma, P. (2002). Stakeholder mapping technique: toward the development of a family firm typology. Paper presented at the Academy of Management meetings, Denver, CO. |

| [99] | Dyer, G. W. Jr. (2006). Examining the “family effect” on firm performance, Family Business Review, 19, 4, 253-273. |

| [100] | Lòpez-Gracia, J. and Sànchez-Andùliar, S. (2007). Financial Structure of the Family Business: Evidence from a Group of Small Spanish Firms, Family Business Review, 20, 1, 269-287. |

| [101] | Antoniou, A., Guney, Y. and Paudyal, K. (2008). The determinants of capital structure: capital market vs bank oriented institutions, Journal of financial and quantitative analysis, 43, 1, 59-92. |

| [102] | Hsiao, C. (1986). Analysis of Panel Data, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. |

| [103] | Baltagi, B. H. (1995). Econometric Analysis of Panel Data, Wiley, Chichester. |

| [104] | Gaud, P., Jani, E., Hoesli, M. and Bender, A. (2003). The capital structure of Swiss companies: an empirical analysis using dynamic panel data. Research Paper Series, International Center for Financial Asset Management and Engineering. |

| [105] | Anderson, T. W. and Hsiao, C. (1982). Formulation and estimation of dynamic models using panel data, Journal of Econometrics, 18, 1, 47-82. |

| [106] | Martinsson, G. (2009). Are there financial constraints for firms investing in skilled employees? Electronic Working Paper Series N. 169, CESIS. |

| [107] | Arellano, M. and Bond, S. R. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58, 277-97. |

| [108] | Sargan, J. D. (1958). The estimation of economic relationships using instrumental variables. Econometrica, 26, 393-415. |

| [109] | Alcock, J., Finn, F. and Tan, K. J. K. (2012). The Determinants of debt maturity in Australian firms, Accounting & Finance, 52, 2, 313-341. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML