-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2015; 4(5): 236-244

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20150405.02

Bank Domestic Credits and Economic Growth Nexus in Nigeria (1980-2013)

Iwedi Marshal1, Igbanibo Dumini Solomon1, Onuegbu Onyekachi2

1PhD Scholars, Department of Banking and Finance, Faculty of Management Sciences, University of Science and Technology, Nkpolu, Nigeria

2Academic Staff, Department of Banking and Finance, College of Management Sciences, Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Iwedi Marshal, PhD Scholars, Department of Banking and Finance, Faculty of Management Sciences, University of Science and Technology, Nkpolu, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The study examined the impact of bank domestic credits on the economic growth of Nigeria. Using time series Nigerian data for the period of thirty three (33) years (1980-2013), credit to private sector, credit to government sector and contingent liability were used as proxy for bank domestic credit while gross domestic product represents economic growth. The augmented Dickey-Fuller unit root test results indicated that the data series achieved stationarity after first differencing at the order 1(1). The relative statistics of the estimated model shows that credit to the private sector (CPS) and Credit to the government sector (CGS) positively and significantly correlate with GDP in the short run. The analysis revealed the existence of poor long run relationship between bank domestic credit indicators and gross domestic product in Nigeria. This study recommends that the managers of the Nigeria economy should fashion out appropriate policies that will enhance the bi-directional flow of influence between the banking sector where investable funds are sourced and the real sector of the economy where goods and services are produced, and there should be efficient and effective utilization of borrowed funds in order to achieve the nominated objective of investment, productivity and economic growth.

Keywords: Bank Domestic Credits, Gross Domestic Product, Cointegration

Cite this paper: Iwedi Marshal, Igbanibo Dumini Solomon, Onuegbu Onyekachi, Bank Domestic Credits and Economic Growth Nexus in Nigeria (1980-2013), International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 4 No. 5, 2015, pp. 236-244. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20150405.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Economic growth has long been considered an important goal of economic policy with a substantial body of research attempting to explain how this goal can be achieved. Most of the empirical studies have focused on explanatory variables selected on the basis of their relevance to policy formulation or base on their theoretical relevance [5]. However, Banks play very important roles in the economic development and growth of any nation. As an important component of the financial system, they channel scarce resources from the surplus economic units to the deficit economic units in an economy (granting credit) as such this activities form part of their existence [31]. The loan resources (Bank Credit) can be in the form of short term credit, medium term credit, long term credit and contingent fund. Thus, these Bank credits to a reasonable extends, exert reasonable influence on the pattern and trend of economic growth in Nigeria.It is an issue for academic debate that the level of economic growth and development determines the extent of sophistication of the banking system as well as the pattern and quantum of bank credit. This is primarily due to the fact that the banking system exists to propel and service economic growth and thus all shocks in the economic growth and development process affect the banking system positively or negatively. Other scholars opine that, as a key participant in the economic growth and development process, Banks attempt to restructure and grow the economy through the pattern of their Credits. However, the importance of banks domestic credit in promoting economic growth has been evidence as credits are obtained by various economic agents to enable them meet operating expenses. For instance business firms obtain credit to buy machinery and equipment, farmers obtain bank credit to purchase seeds, fertilizers, erect various kinds of farm buildings. Government bodies obtain credit to meet various kinds of recurrent and capital expenditures. Furthermore, individuals and families also take bank credit to buy and pay for goods and services [3]. In Nigeria, the major objective of successive government is to achieve the desired growth, this is evident during the pre-independence era (colonial period) where the government focus was on the provision of physical infrastructure in the belief, in line with the prevailing economic ideas, that the facilities would induce the private investments that would produce the desired growth. After independence the government becomes more directly involved in promoting economic growth. The thinking this time was to nurture private entrepreneurs and mobilize needed domestic resources (credit) for investment in some preferred sectors. This brought banks and their intermediation function into prominence in the economic history of Nigeria [15]. “According to [53], loanable funds result out of planned and mobilized savings”. Accumulated savings when invested translate into capital formation which is a stock of real productive asset [53]. Banks domestic credit to the Nigerian economy has been on the increase over the years. “According to [11], Bank Domestic credit to the core private sector by the deposit money Banks grew by 98.7%, outstanding credit to aquaculture, solid minerals, exports and manufacturing in 2007 stood at 3.1, 10.2, 1.4 and 10.1 percent respectively”. Credit flows to the core private sector in 2007 amounted to N2.3 billion in making domestic credit available, banks are rendering a great social service, because through their actions, production is increased, capital investment are expanded and the output level of goods and services are expected to grow higher [1].Moreover, the dominant position of banks in the Nigerian economy becomes more evident when one considers their size, structure, assets structure, deposit structure and the volume of credits they grant to the different economic units at play in the system. Given these, it is only rational to expect banks credit to service as prime catalysts to economic growth and development [16]. The objective of bank consolidation was to increases the size of the banks. This was based on the belief that with increase size these banks would become stronger, resilient to shocks and capable of funding the real sector and by extension, enhancing economic growth [15].In view of this controversy as to whether the pattern of bank domestic credit stimulates economic growth or growth in the economy influences bank credit, there remain a gap in understanding the causal relationship between credit to the private sector, credit to the government sector and contingent fund, and economic growth. Therefore, this study attempt to bridge this gap in finance literature by examining whether banks domestic credit to the economy has any effect in stimulating economic growth in Nigeria.

2. Theoretical Framework and Empirical Studies

- A. Theory of Financial Intermediation Quoting the work of [38] “credit is an important aspect of financial intermediation that provides funds to those economic entities that can put them to the most productive use”. Theoretical studies have established the relationship that exists between financial intermediation and economic growth. For instance, [49], [19], [37] and [50], in their studies, strongly emphasized the role of financial intermediation in economic growth. In the same vein, [20] observed that financial development can lead to rapid growth. In a related study, [21] explained that development of banks and efficient financial intermediation contributes to economic growth by channeling savings to high productive activities and reduction of liquidity risks. They therefore concluded that financial intermediation leads to growth. Based on this assertion, this study examines the extent to which intermediation or credit to various sectors of the economy has influenced economic growth in Nigeria.B. Theory of Economic Growth There are numerous growth models in literature. However, there is no consensus as to which strategy will achieve the best success. “According to [38], the achievement of sustained growth requires minimum levels of skills and literacy on the part of the population, a shift from personal or family organization to large scale unit”. Some of these existing growth models are Two-Gap Model, Marxian Theory, Schumpeterian Theory, Harrod-Domar Theory of Growth, Neo-Classical Model of Growth, and Endogenous Growth Theory. The growth models relevant to this study are Neo-Classical Model of Growth, and Endogenous Growth Theory, since these growth models explain the situation in developing economies such as Nigeria, Ghana, etc.Neo-Classical Model of Growth: The neo-classical model of growth was first devised by Robert Solow. The model believes that a sustained increase in capital investment increases the growth rate only temporarily. This is because the ratio of capital to labour goes up (there is more capital available for each worker to use) but the marginal product of additional units of capital is assumed to decline and the economy eventually moves back to a long-term growth path, with real GDP growing at the same rate as the workforce plus a factor to reflect improving “productivity”. A “steady-state growth path” is reached when output, capital and labour are all growing at the same rate, so output per worker and capital per worker are constant. Neo-classical economists believe that to raise an economy’s long term trend rate of growth requires an increase in the labour supply and an improvement in the productivity of labour and capital. Differences in the rate of technological change are said to explain much of the variation in economic growth between developed countries. The neo-classical model treats productivity improvements as an ‘exogenous” variable meaning that productivity is assumed to be independent of capital investment [28].“According to [39], based on Solow’s analysis of the American data from 1909 to 1949, they observed that 87.5% of economic growth within the period was attributable to technological change and 12.5% to the increased use of capital. The result of the growth model was that financial institutions had only minor influence on the rate of investment in physical capital and the changes in investment are viewed as having only minor effects on economic growth”.Endogenous Growth Theory: Endogenous growth theory or new growth theory was developed in the 1980s by [48], [36], and [47], among other economists as a response to criticism of the neo-classical growth model. The endogenous growth theory holds that policy measures can have an impact on the long-run growth rate of an economy. The growth model is one in which the long-run growth rate is determined by variables within the model, not an exogenous rate of technological progress as in a neoclassical growth model. [32], explained that the endogenous growth model emphasizes technical progress resulting from the rate of investment, the size of the capital stock and the stock of human capital.In an endogenous growth model, [39] observed that financial development can affect growth in three ways, which are: raising the efficiency of financial intermediation, increasing the social marginal productivity of capital and influencing the private savings rate. This means that a financial institution can affect economic growth by efficiently carrying out its functions, among which is the provision of credit.C. Empirical StudiesAlthough there exist an extensive body of literature on the link between finance and economic growth, there is no consensus on the effect of explanatory variables on economic growth. See for example, [33], [34], [46] and [35].The direction of causal relationship between economic growth and the banking sector is one area of contention amongst economists. [49] “for example was a strong advocate of the role of the banking sector credit in stimulating economic growth and stated that the banker stands between those who wish to form new combinations and the possessors of productive means. He is essentially a phenomenon of development, though only when no central authority directs the social process. He makes possible the carrying out of new combinations, authorizes people, in the name of the society as it were, to form them. He is the ephod of the exchange economy.” [24], however argue that banking activity and profitability are a function of economic growth.“According to [6], banking sector openness had a direct and indirect effect on economic growth through a combination of improvement in access to financial services, and the efficiency of financial intermediaries as both of these cause a lowering of costs of financing which in turn stimulates capital accumulation and economic growth”. However, [7] find that soft budget constraints and repeated bank bailouts by governments were a function of poor quality of loan portfolios, the absence of collateral, low bank capitalization, and political pressure to refinance unprofitable firms in transitional economies. [23], also find that the effect of financial development on economic growth of Northern Cyprus although positive, was negligible.[44], also asserted that other determinants of economic growth especially in cross-section studies exist in the literature such as the years of schooling (human capital), black market premiums, bureaucratic efficiency, corruptions etc. However, data on these variables are usually obtained from periodic surveys and hence consistent time series are unavailable.” [49], argued that the banking sector (DMBs) plays a crucial role in channeling finance and investments to productive agents within the economy and thus act as catalysts of economic growth. The main implication of this theory therefore, is that banking policies which embrace openness, competition, change and innovation will promote economic growth. Conversely, policies which have the effect of restricting or slowing banking reforms by protecting or favoring particular industries or firms are likely, over time, to unsustainable economic growth.According to [27] “Sustained economic growth is narrowly defined as sustained growth in income per person”. The effect of rising price level thus inflation will inhibit the development of the financial sector and result in financial repression”. High inflation will also discourage any long term financial contracting and financial intermediaries will tend to maintain very liquid portfolios. Thus, in an inflationary environment, intermediaries will be less eager to provide long-term financing for capital formation and growth; both lenders and borrowers will also be less willing to enter long-term nominal contracts.Theoretical expectation is that ceteris paribus, loanable funds available for lending increases when the size of capital available to banks increases. In addition, the more the funding available to the private sector, the less the crowding out effect and the more that can be used to promote private enterprise and production. This is however subject to the Central Bank of Nigeria prudential guidelines which requires that the total outstanding exposure by a bank to any single person or a group of related borrowers must not at any time exceed 20 percent of the bank’s.Shareholders fund. The size of bank-led funding is always limited while government capacity to demand for bank loans is always significant and directly affects interest rates. The availability of loanable funds to the private sector is a function of government’s propensity for loanable funds. A reduction by the banking sector in funding government expenditures would result in a fall in interest rates and demand for loanable funds will decline thereby the private sector gaining access to secure the loans for productive activities.Referring to the 2004-2005 banking consolidation reforms in Nigeria, [43] explained that “To strengthen the financial sector and improve availability of domestic credit to the private sector, a bank consolidation exercise was launched in mid- 2004. The Central Bank of Nigeria requested all deposit banks to raise their minimum capital base from about US$15 million to US$ 192 million by the end of 2005. In the process of meeting the new capital requirements, banks raised the equivalent of about $3 billion from domestic capital markets and attracted about $652 million of FDI into the Nigerian banking sector. However recent study by [25], using the GMM technique developed by [41] and [42] conducted causality testing analysis on 13 Asian developing countries. The result is in agreement with other causality studies by [10]; [17] and [14]. They found that financial development promotes growth, thus supporting the old Schumpeterian hypothesis.In furtherance to the above studies, a good number of other recent studies lend further credence to a causal relationship between credit and economic growth. [28] Report detected a statistically significant impact of credit growth on GDP growth. Specifically, it was revealed. that “a credit squeeze and a credit spread evenly over three quarters in USA will reduce GDP growth by about 0.8% and 1.4% points year-on-year respectively assuming no other supply shocks to the system”.[20], also observed that financial institutions produce better information, improve resource allocation (through financing firms with the best technology) and thereby induce growth. Several research works on finance and growth support a positive correlation between the two variables while causality emanates from finance to growth.Following the line of argument of the previous researchers was [22], who used two growth models to examine the impact of financial intermediation on economic growth. He stated that economic growth is no longer believed to happen for exogenous reasons; instead governments through appropriate policies particularly with regard to financial market can influence it. The recent work of [9] in a review of the various analytical methods used in finance literature, found strong evidence that financial development is important for growth. To them, it is crucial to motivate policymakers to prioritize financial sector policies and devote attention to policy determinants of financial development as a mechanism for promoting growth.That notwithstanding, most studies provide evidence of a positive effect of finance or financial market development on economic growth [29]; [46], [33] for example, find a positive effect of finance on economic growth based on cross country growth regressions using data for 77 countries. However, a re-examination by [18] of the analysis by [35] indicate a weak effect at best using time series analysis, [26], find a bilateral causal relationship between financial development and economic growth for Greece. The recent work of Lately, empirical work linking banking sector developments to real activity using indicators such as bank credit has started growing out of the broad literature documenting the relationship between financial development and economic growth [8]. In attempt to improve upon measurements used in cross-country studies on finance and growth, [8] measure bank development as bank credit to private sector divided by GDP.The work of [54] on the impact of access to bank credit and the economic performance of key economic sectors using sectoral panel data for Kenya find a positive and significant impact of credit on sectoral gross domestic product measured as real value added.In the same vein, the empirical result of [45] showed a positive relationship exists between the lagged values of total private savings, private sector credit, public sector credit, interest rate spread, exchange rates and economic growth. [15], study on Bank and Economic growth in Nigeria shows an insignificant impact of bank intermediation variables on economic growth. The poor performance of these variables indicate that other variables such as human resources, social infrastructure, political stability and technology play more robust role in economic growth in Nigeria than banks. [40], revealed a significant negative effect of DMBs credit on agricultural productivity; he said that such funds by implication are diverted to other unproductive sector of the economy. For a detailed review of literature on finance and economic growth, see [38]. This work takes a regression from cross-country studies by using Nigeria as a case study to examine the effect deposit money banks domestic credit on the economic performance of Nigeria. Although Nigeria vision of becoming “a globally competitive and prosperous country” by 2020 is pegged on the economic success of some key sectors of the economy [12], one of the constraints to sectorial growth has been hailed to be inadequate access to domestic credit. Credit provision is thus, expected to play a role as the country forges forward with the realization of its growth and development objectives.

3. Methodology

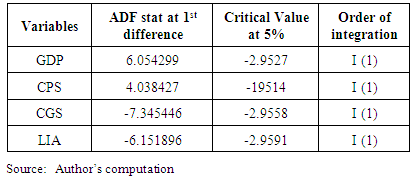

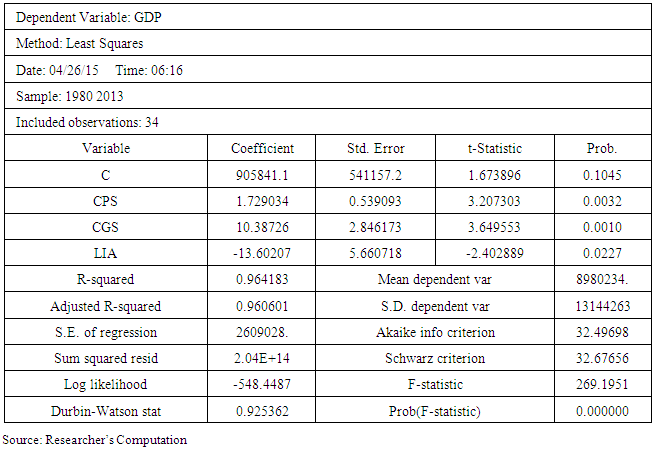

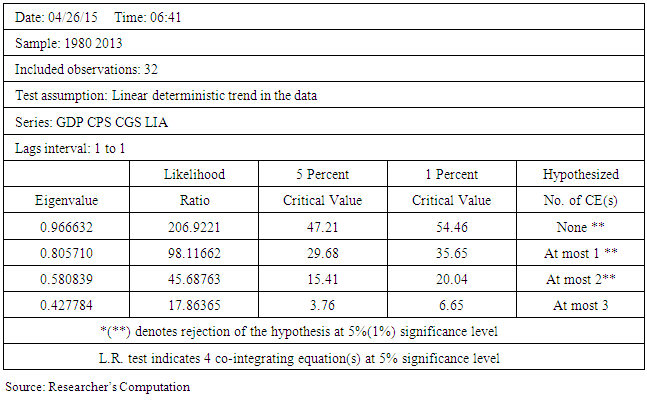

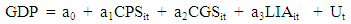

- The analytical framework of this study includes pre estimation analysis such as descriptive statistics and stationarity test. This is to reveal the behaviour of the data on the variables. The stationarity test: We investigate the stationarity of the variables, non stationarity could lead to spurious regression results. Such spurious relationship between/ among variables may be evident in time series data that exhibit non-stationary. Ordinary Least Square Regresion: This test result will reveal the predictive ability of the model as well as the relative statistics of the variables in the short run. Test for long- run relationship: the test for the presence of long-run equilibrium relationship is carried out based on the [30] multivariate cointegration technique. The data used for the study is basically secondary in nature. This data is obtained from the publications of the Central Bank of Nigeria Statistical Bulletin (2013). Data were collected on Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Credit to Private Sector (CPS), Credit to Government Sector (CGS), and Contingent Liabilities (LIA). MODEL SPECIFICATIONThis study construct and utilized a single bank credit – economic growth model with three predictor variables linearly in the functional form as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

4. Empirical Results

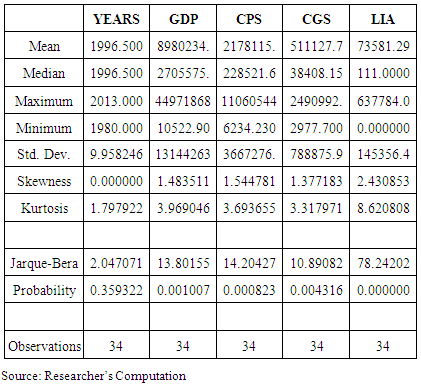

- A. DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS RESULTIn table 1 above, the average amount in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Value for the 33 year period covered by this study is N8, 980,234. While the Mean values of CPS, CGS and LIA are N2, 178,115, N511, 127.70, and N73, 581.29, respectively. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has the highest average value in the Model seconded by credit to the private sector (CPS). GDP has it mean value within the years 2004, Credit to private sector’s average value was attained within the year 2006 while the Credit to government sector (CGS) and Contingent Liability (LIA) has their mean value in 2004 and 2004 respectively. The Median value best described the centers for each data series in the model, such that the values 2,705,575; 228,521.60; 38,408.15; and 111.00; provides a more valid measure of the central location of the different time series – GDP, CPS, CGS, and LIA respectively. The GDP output level ranges from 10,522.90 to 44,971,868 while the range of the performance measures of the bank domestic credit measures – CPS, CGS, and LIA, are from 6,234.23 to 11,060,544; 2,977.70 to 2,490,992 and from 0.0000 to 637,784.0 respectively. GDP has the highest maximum value of 44,971,868 seconded by CPS with a maximum Value of 11,060,544 which was attained in the year 2013. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), credit to private sector (CPS) and credit to government sector (CGS) have the first three highest standard deviation in the Model. This suggests that GDP, CPS and CGS are the most volatile variable variables. This is manifested in the extent of their dispersion from the mean. The other variable LIA, seem to be clustered more closely about the mean. Since the mean of each of the variable in the model is greater than the median, it suggests that the variables are skewed to the right towards normality.

|

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

- This study x-rays three basic bank domestic credit performance indicators as predictors of economic growth in Nigeria. A review of related empirical literature on the relationship between the correlates was carried out. Though a number of studies on Nigerian economy and the banking sector have been carried out over the years, there seems to be, weak evidence for a strong correlation and some of them have been in conclusive. This study however adjusted the data make-up to include 2013 data and also employed a more interesting econometric procedure to carry out this investigation. The findings of this study leads to various conclusive remarks. The results showed evidence for strong and positive correlation between CPS and GDP, and between CGS and GDP in the short run. The study recommends that policy makers should fashion out appropriate policies that will enhance the bi-directional flow of influence between the banking sector where investable funds are sourced and the real sector of the economy where goods and services are produced. There should be efficient and effective utilization of borrowed funds in order to achieve the nominated objective of investment, productivity and economic growth.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML