-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2015; 4(4): 206-213

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20150404.02

Incentives and Constraints of Real Earnings Management: The Literature Review

Mouna Sellami

Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Management of Sfax, Tunisia

Correspondence to: Mouna Sellami, Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Management of Sfax, Tunisia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

It is recently that researchers in the field of accounting have paid attention to the practice of real earnings management. The aim of this paper is to conduct a literature review on the subject. More precisely, I tried to better define real earnings management and to clarify the various forms of real earnings management. Also, this paper reviews the different incentives and constraints to the real earnings management. Finally, a discussion and a number of opportunities for future research on real earnings management are set out in this paper.

Keywords: Real earnings management, Real activities, Incentives, Constraints

Cite this paper: Mouna Sellami, Incentives and Constraints of Real Earnings Management: The Literature Review, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 4 No. 4, 2015, pp. 206-213. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20150404.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Earnings management has been the subject of several studies in the accounting field. Healy and Whalen (1999, p. 368) state that: “Earnings management occurs when managers use judgment in financial reporting and in structuring transactions to alter financial reports to either mislead some stakeholders about the underlying economic performance of the company or to influence contractual outcomes that depend on reported accounting numbers”. Thus, based on the definition of earnings management discussed by Healy and Whalen (1999), two types of earnings management which executives can use to alter earnings are documented: earnings management through accounting decisions or accruals - described as “Accounting Earnings Management” and earnings management through real business decisions or real activities - identified as “Real Earnings Management, REM”. In general, prior research1 has focused almost exclusively to the practice of accounting earnings management. We are witnessing the last few years to the publication of several research papers on the subject of REM (e.g. Gunny, 2005; Roychowdhury, 2006; Xu et al. 2007; Cohen et al. 2008; Gunny, 2010; Seybert, 2010; Taylor and Xu, 2010; Zang, 2012). Given that the REM is considered as a new field of research, it contains unanswered questions. Among these questions, as mentioned by XU et al. (2007), is the factors that induce and mitigate REM. The purpose of this paper is to make a review of literature of incentives and constraints of REM. It attempts to offer a few additional observations related to this issue. I believe that understanding these factors is important to better identifying the distortion of earnings by real activities.To conduct the review, I focus on accounting literature publishing in leading accounting journals and on some major working paper related the topic of the research.Our paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents definitions and various forms of REM. Section 3 deals with the incentives of REM. Section 4 covers constraints of REM. A discussion and future avenue of research will be the subject of section 5. The last section concludes the paper.

2. Definition and Various Forms of Real Earnings Management

- In this section, I first review some definitions of REM to better understand the practice of REM and conclude a definition. Following this, I outline the various forms of REM that managers can use to alter earnings management.

2.1. Definitions of Real Earnings Management

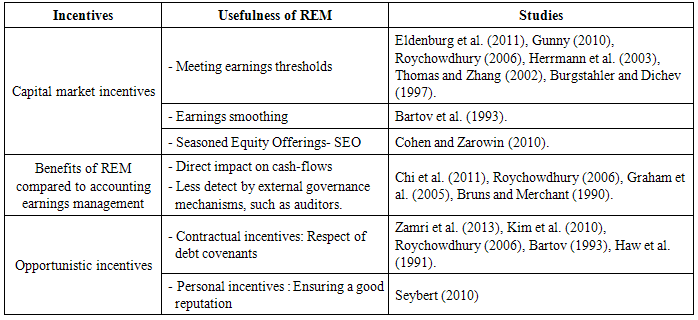

- Shipper (1989, p. 92) is the first who introduced the concept of REM in the definition of earnings management2. More precisely, he considers that it is: “accomplished by timing investment or financing decisions to alter reported earnings or some subset of it”. For its part, Janin (2000) states that: REM involves real business activities that have a direct impact on operating cash-flows. Also, Ewert and Wagenhofer (2005 p. 1102) describe REM as “changes the timing or structuring of real business transactions to alter earnings”. More recently, Roychowdhury (2006, p. 337) defines REM as: “Departures from normal operational practices, motivated by managers desire to mislead at least some stakeholders into believing certain financial reporting goals have been met in the normal course of operations”.According to the definitions of Shipper (1989), Janin (2000), Ewert and Wagenhofer (2005) and Roychowdhury (2006), I conclude that REM: First, alters earnings through the timing or the magnitude of real decisions (operating, investing or financing activities) according to the desired earnings target. Second, has a direct impact on the operating cash flows and consequently on the earnings. In other word, it is an earnings management practice related specifically to cash accounting3. Finally, it intended to mislead stakeholders about the real performance of the company. In other words, managers manipulate real decisions to serve their personal interests. In this case, I can say that management decisions do not lead to a credible representation of economic performance.In summary, I define the REM as: “change on the timing or structuring of management decision (real business decisions related to the operating, investing or financing activities), that have a direct impact on cash flows and thus in earnings, motivated by managers’ desire to mislead stakeholders about the real performance of the company”.My definition is summarized in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Definition of real earnings management |

2.2. Various Forms of Real Earnings Management

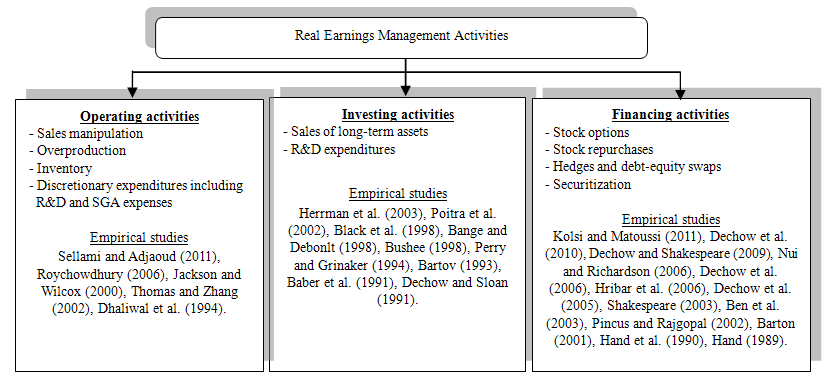

- While accruals earnings management occurs when managers manipulate reported earnings by exploiting the accounting discretion allowed under accounting standards, the REM involves management attempts to alter reported earnings by adjusting the timing and scale of underlying business activities (Xu et al. 2007). REM includes various forms which are qualified by management decisions or real activities, i.e., sales; production; discretionary expenditure including expenditure of research and development (R&D) and selling, general and administrative expenses (SGA), advertising expenses and maintenance expenditures, asset sales. The various forms of REM are not a simple accounting choice and estimate but rather a strategic management decisions that deviate from normal business practices and which have a direct impact on cash flows. Xu et al. (2007) categorized the management decisions into three categories: operating, investment and financing decisions (see Figure 2 for a detailed list of various forms of REM with their empirical evidence4).

| Figure 2. Various forms of real earnings management |

3. Incentives of Real Earnings Management

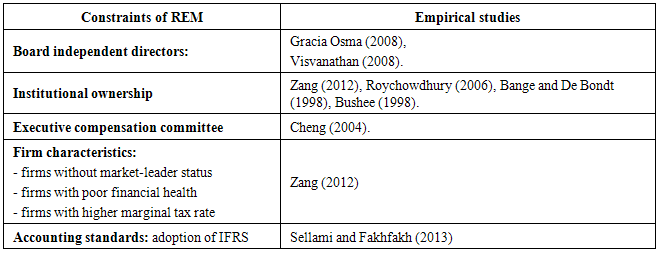

- I identify three types of incentives to REM: capital market incentives, opportunistic incentives and benefits of REM compared to accounting earnings management.

3.1. Capital Market Motivations

- The interaction between accounting information and the reaction of the stock market can pushed the managers to manage earnings through real activities. In this case, I talk about capital market incentives. I recognize three capital market motivations for REM: meeting earnings management threshold, earnings smoothing and specific stock market situations.For meeting earnings management threshold, prior literature has indicated that the REM is guided primarily by the desire to meet or beat certain earnings management thresholds. Some researchers (Burgstahler and Dichev, 1997; Thomas and Zhang, 2002; Roychowdhury, 2006; Eldenburg et al. 2011; Gunny, 2010) found evidence that firms engage in REM to avoid small losses and earnings decreases. In other hand, Herrmann et al. (2003) find that Japanese manager’s use discretion via income from asset sales to reduce management forecast error. Whereas, Roychowdhury (2006) finds some evidence consistent with the notion that managers engage in REM activities to meet analysts’ forecasts.For earnings smoothing hypothesis which predicts that earnings are manipulated to reduce fluctuation around some level that is considered normal for the firm (Ronen and Sadan, 1981). Trueman and Titman (1988) analyze income smoothing as signal to band markets. Consistent with this, I find one article that examined real earning management with income smoothing: Bartov et al. (1993) show that managers manipulate earnings through asset sales in order to reduce the variations of earnings over time. More precisely, the finding demonstrates that income from asset sales is significantly higher for firms that exhibit decreases in annual earnings than for firm experiencing increases.Finally, for the specific stock market situations, a recent study conduct by Cohen and Zarowin (2010) contribute to the literature of REM by showing that SEO firms engage in real activities manipulation in the year of the SEO, and the decline in post-SEO performance due to the real activities management is more severe than that due to accrual management. Their findings show the importance of REM activities around a specific corporate finance event, SEOs.

3.2. Opportunistic Motivations

- REM can be used by managers as a means to satisfy their own interests. In this case I speak of opportunistic incentives. The positive accounting theory initiated by Watts and Zimmerman (1978, 1986), aims to predict and explain accounting practices. It explains the use of managers to earnings management by the existence of agency relationships (Jensen and Meckling, 1976) and by the presence of opportunism in the behavior of managers. I draw two main opportunistic motivations for real management which are identified as: Contractual incentives (agency relationship) and personal incentives (ensuring a good reputation).The contractual incentives are linked to the agency relationship between managers and stakeholders, namely the creditors and shareholders. Among the factors advanced to explain the earnings management in the context of politico-contractual theory is the maximizing the wealth of managers, minimizing the cost of debt and minimizing political cost. I find that a several studies have examined REM only with the motivation of minimizing the cost of debt: Zamri et al. (2013), Kim et al. (2010), Roychowdhury (2006), Bartov (1993), and Haw et al. (1991).The personal incentives are related to the manager's use of him opportunistic behavior to beat informal goals. Indeed, managers are motivated to show a good image of their company towards its stakeholders. Experiments conducted by Seybert (2010)5 show that the capitalization of research and development in term of overinvestment is a real management tool that leads managers to ensure a good reputation.

3.3. Advantages of Real Earnings Management Compared to Accounting Earnings Management

- Some researchers (Bruns and Merchant, 1990 and Graham et al. 2005) argued that managers show a willingness to manage their earnings through real activities rather than accounting techniques. This preference to use the real management decision can be explained by the benefits presented by REM compared to accounting earnings management.REM has the advantage that it has a direct impact on cash-flows of the company. Thus, this can help companies highly leveraged to generate cash and pay down their loans. However, the accounting earnings management does not offer this flexibility. It only has an impact on earnings. Another advantage of altering real activities to manipulate earnings is that auditors and regulators are less likely to be concerned with such behavior. REM is often difficult to detect because it is properly disclosed in the financial statements (Shipper, 1989). Whereas, accounting earnings management is subject to oversight of auditors because it is mainly based on accounting decisions. Chi et al. (2011) find that higher audit quality is associated with greater levels of REM. In addition, REM is a mean that allows manager to avoid litigation risk, (Roychowdhury, 2006). Cohen et al. (2008) document that managers switch from accruals management to REM on response to increased litigation risk after the passage of SOX. Finally, accruals-based earnings management has a constraint that is reversal over time. So managers must take into consideration the implication of their discretion on current accruals for future earnings. However, REM is less subject to this constraint.Consistent with these arguments state above, Xu et al. (2007) document that the accounting earnings management via accruals is likely to be more costly to mangers because they cannot legally be held responsible for REM as long as the outcomes of REM are properly disclosed in the financial statements. Table 1 below summarizes the incentives and usefulness of the REM according to previous studies.

|

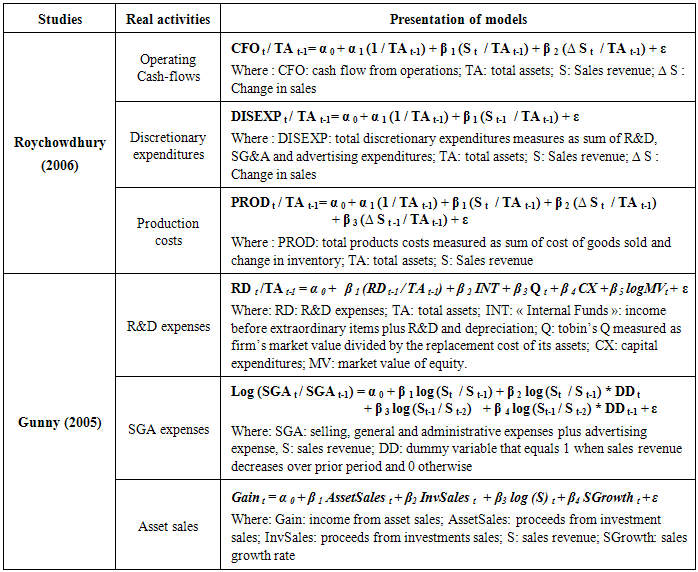

4. Constraints of Real Earnings Management

- Some studies have sought to view whether and what types of corporate governance characteristics constrain REM. Through the literature review, I note that board independent directors, institutional investors, executive compensation committee and firm characteristics and accounting standards could play a role in constraining of REM.

4.1. Board Independent Directors

- Gracia Osma (2008) analyzed the monitoring role of board directors over one set of REM decisions: R&D spending. The result indicate that independent directors reduces the probability that a firm will cut R&D spending as a result of previous period disappointments, or to push the earnings into meeting current-period targets. Also, Visvanathan (2008) examined several board characteristics (independence, size and CEO duality) and audit committee characteristics (size, independence and meeting of audit committee). As result, he finds that overall corporate governance characteristics that have been found to be significant in limiting accruals based earnings management are not significant in restraining REM. He shows that only a higher proportion of independent director help to restrain REM.Generally, the two studies show that only board independent directors deter REM practices.

4.2. Institutional Ownership

- A number of studies demonstrated that institutional investors play a monitoring role in reducing real activities manipulation: Bange and De Bondt (1998), Bushee (1998), Roychowdhury, (2006) and Zang (2012).

4.3. Executive Compensation Committee

- Cheng (2004) examined the impact of executive compensation committee on REM via R&D spending. She argued that this factor mitigates REM.

4.4. Firms Characteristics

- Other factors related to the firm characteristics could mitigate REM such as: firms without market-leader status, firms with poor financial health and firms with higher marginal tax rates, Zang (2012).

4.5. Accounting Standards

- There is current debate on whether IFRS can play an effective role in reducing earnings management by limiting opportunistic management discretions in managing real activities. In this issue, I identify a recent paper of Sellami and Fakhfakh (2013) which demonstrate that the REM is less associated with the obligatory implementation of IFRS.Table 2 below recapitulates the constraints of REM and the empirical studies that have examined this issue.

|

5. Discussions and Suggestions for Future Research

- Despite the increasing interest in and importance of REM, I think there are many challenges in studying this subject. One is that there is little progress in determining new models to measure real earnings management. The most empirical previous studies in the REM literature use the measures from Roychowdhury (2006). They do not study the properties of alternative REM measures and the statistical tests based on them. In this issues, I find a recent research paper of Cohen et al. (2015) which demonstrate that the traditional REM measures used to date in the literature are severely mis-specified in that their Type I error rates differ significantly from nominal significance levels. The paper highlights the importance of using performance-matched REM measures when testing hypotheses related to managers’ incentives to manipulate real activities to ensure that reliable inferences are drawn from the analysis. Besides, I have identified little research concerning corporate governance initiatives to mitigate the opportunism managerial by manipulating real activities. For example, two papers (Chi et al. 2011, Sun et al. 2014) showed that audit quality and audit committees are associated positively with the REM. I think it will be interesting to see why theses corporate governance mechanisms could not restrain REM over time and how auditors and audit committees view the use of REM. As research perspectives, it will be interesting to consider many other factors not yet examined which could drive REM such as compensation contract, political cost. Besides, the relation of REM with other context such as: Management Buyouts of Public Stockholders and change in CEO could be explored in future research. Finally, it seems interesting to explore how and whether the flexibility of accounting standards affects the scope of REM.

6. Conclusions

- This paper aims to summarize some studies related to REM literature. Specifically, this paper offers a better comprehension of the practice of REM and this is by proposing a definition after reading other definition presented in the literature. It also outlines the various forms of REM, incentives and constraints of REM. Finally, a discussions and a variety of directions for future research are set out in this paper. The literature review allows me to conclude that REM remains a fertile ground for academics research.

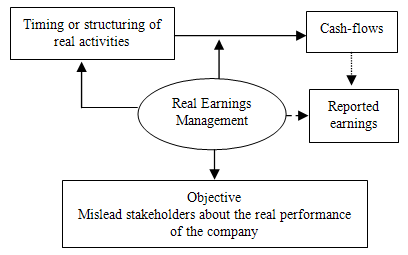

Appendix

- I synthesize in Table 3 the empirical models proposed by Roychowdhury (2006) and Gunny (2005). These allow us to measure the normal part of every real activity: (i.e., Operating cash-flows, discretionary expenditures, Production, R&D expenses, SGA expenses and asset sales).

|

Notes

- 1. e.g., Healy, 1985; Guidry et al., 1999; Defond and Jiambalvo, 1994; Kasznik, 1999; Healy and Wahlen, 1999; Dechow and Skinner, 2000; Kothari, 2001. 2. Shipper (1989) “... A minor extension of this definition would encompass ‘‘real’’ earnings management […]”3. We reminder that earnings are the sum of accruals and operating cash-flows.4. This list of REM activities is not discussed in detail in the current paper. For more details, we can refer to the study of Xu et al. (2007). Gunny (2005) and Rochowdhury (2006) develops models to estimate the normal level of real activities. The appendix illustrates the models used in order to measure the various forms of REM such as sales, production, discretionary expenditure (R&D and SGA expenditures) and asset sales. 5. In an experiment utilizing M.B.A. student participants, Seybert (2010) finds that managers responsible for initiating an R&D project are more likely to overinvest when R&D is capitalized. He shows that high self-monitors are most likely to overinvest, suggesting that reputation concerns contribute to this behavior. A follow-up survey reveals that, when R&D is capitalized, experienced executives anticipate overinvestment and expect project abandonment to have a stronger negative impact on the responsible manager’s reputation and future prospects at their firm.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML