-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2015; 4(3): 145-152

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20150403.01

Determinants of Environmental Disclosures in Nigeria: A Case Study of Oil and Gas Companies

Ndukwe O. Dibia1, John Chika Onwuchekwa2

1Department of Accounting, Abia State University, Uturu, Abia State, Nigeria

2Department of Accounting, Rhema University, Aba, Abia State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ndukwe O. Dibia, Department of Accounting, Abia State University, Uturu, Abia State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The study is an empirical analysis of the determinants of environmental disclosures using oil and gas companies in Nigeria. Specifically, the study objectives are to examine the effect of Firm size, Profit, Leverage and Audit firm type on environmental disclosures. The cross-sectional research design was utilized in undertaking the study. A sample of 15 companies drawn from the oil and gas sectors of the Nigerian stock exchange for 2008-2013 financial years was used for the study. Secondary data was sourced from the annual reports of the sampled companies while the Binary regression technique was used as the data analysis method. The finding of the study shows that firstly; there is a significant relationship between company size and corporate social responsibity disclosures. Secondly there is no significant relationship between Profit and corporate social responsibity disclosures. Thirdly, there is no significant relationship between Leverage and corporate social responsibity disclosures. Finally, there is no significant relationship between audit firm type and corporate social responsibity disclosures. The study concludes that the voluntary stance of environmental reporting has often be used as a cliché for companies to under report their effect on the environment and this is responsible for the negligence of several corporate entities with regards to corporate social and environmental reporting. The study recommends that incentives be put in place to motivate disclosures.

Keywords: Environmental reporting, Financial reporting. Firm size, Profitability, Binary regression

Cite this paper: Ndukwe O. Dibia, John Chika Onwuchekwa, Determinants of Environmental Disclosures in Nigeria: A Case Study of Oil and Gas Companies, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 4 No. 3, 2015, pp. 145-152. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20150403.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Environmental disclosure by corporations has been increasing steadily in both size and complexity over the last two decades (Smith, 2003). Research attention over the years has attempted to understand and explain this area of corporate reporting which appears to lie outside the conventional domains of accounting disclosures. The evolving challenge in contemporary business firms is the need to reconfigure their performance indices to incorporate societal and environmental concerns as part of the overall objective of business. Environmental and social reporting provides a strategic framework for achieving this holistic re-appraisal of corporate performance. Although it is not a new concept, environmental disclosures remain an interesting area of discourse for academics and an intensely debatable issue for business managers and their stakeholders. According to Deegan and Rankin (1996) corporate environmental reporting refers to the way and manner by which a company communicates the environmental effects of its activities to particular interest groups within society and to society at large. Companies through the process of environmental communication may seek to influence the public’s perception towards their operations. They attempt to create a good image (Deegan and Rankin, 1999). The increasing demand for companies to be socially responsible seems to have witnessed considerable perceptual divergences especially within the context of the stakeholder-shareholder debate. The idea which underlies the “shareholder perspective” is that the only responsibility of managers is to serve the interests of shareholders in the best possible way, using corporate resources to increase the wealth of the latter by seeking profits. In contrast, the “stakeholder perspective” suggests that besides shareholders, other groups or constituents are affected by a company’s activities (such as employees or the local community), and have to be considered in managers’ decisions, possibly equally with shareholders. By reporting environmental information, a firm addresses the information needs of stakeholders and provides a basis for dialogue between the firm and its stakeholders. As a critical avenue of stakeholder management, environmental reporting shapes external perceptions of the firm, helps relevant stakeholders assess whether the firm is a good corporate citizen, and ultimately justifies the firm’s continued existence to its stakeholders. However, environmental reporting has developed rather voluntarily and this implies that companies can choose what to disclose and may even decide not to. Research attention (Sharfman and Fernandoi 2008; Schneider 2010; Roberts 1992; Mgbame 2012) in this regard has been focused largely on why and what factors could influence a company to engage in environmental disclosures voluntarily. Studies (Hackson and Milne 1996; Adams and Hart, 1998) highlighted the importance of the company size. Connors and Gao (2009), Sharfman and Fernandoi (2008), Schneider (2010) examines the role of leverage. Dye and Sridha (1995). Holthausen and Leftwich (1983) have considered the role of industry type. Roberts (1992), Mgbame (2012) have also examined the role of profitability. However, the research evidence in this regards has been inconclusive and the role of the firm specific factors have been vacillating indicating that the issues are still quite unresolved in the literature and this defines the contribution and relevance of the study. Furthermore, there is also a knowledge gap about how corporate characteristics will influence voluntary reporting for developed and developing economies as the magnitude, level of awareness and implications of environmental cost differs considerably. The focus of the study is to examine the determinants of environmental disclosures in Nigeria using companies in the oil and gas sector.

2. Hypothesis

- Our study was based on the hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between environmental disclosure on one hand and each of company size, profitability, leverage and Auditor type on the other.

3. Literature Review

- Ingram & Frazier (1980) examined the association between the content of corporate environmental disclosure and corporate financial performance. The study was concerned with a lack of corporate social responsibility disclosures in annual reports due to their voluntary nature. The authors scored environmental disclosures in 20 pre-selected content categories along four dimensions; evidence, time, specificity, and theme. Ingram and Frazier (1980) proxied environmental performance by a performance index devised by the Council on Economic Priorities (CEP), a non-profit organization specialising in the analysis of corporate social activities. Forty firms were selected from the 50 firms that were monitored by the CEP. Regression results indicated no association between environmental disclosure and environmental performance.In Malaysia, Trotman & Bradley (1981) using the content analysis technique examined the association between social sustainability reporting and characteristics of companies. Findings from the study suggest that a positive relationship exist between firms’ financial leverage and the extent of voluntary disclosure. However, findings from related literatures by Chow & Wong-Boren (1987), Ahmed & Nicolls (1994) and Mohamed & Tamoi (2006) found no statistical relationship between financial leverage and voluntary disclosure. Deegan (1994) has conducted a study on the incentives of Australian firms to provide environmental information within their annual reports voluntarily. Using a political cost framework, hypotheses were developed which link the extent of environmental disclosures with a measure of the firm’s perceived effects on the environment. A sample of 197 firms was obtained from Australian Graduate School of Management annual reports file for the year 1991. The results indicate that firms which operate in industries which are perceived as environmental damaging are significantly more likely to provide positive environmental information within their annual reports than are other firms. Gamble, Hsu, Kite and Radtke (1995) investigated the quality of environmental reporting practices and annual reports of 234 companies in twelve industries in the United States, between 1986 and 1991. An instrument was designed to measure the content of environmental disclosures, and descriptive reporting codes were used, based on the manner in which the sample firms disclosed environmental information. Companies in the sample were from industries thought to have the greatest potential for environmental impact; oil and gas chemicals, plastics, soap, detergent and toilet preparations, perfume, petroleum refining, steel works and blast furnaces and hazardous waste management. The main findings were that certain industries, for example petroleum refining, hazardous waste management and steel manufacturing were judged to have provided the highest quality of disclosures in annual reports. Bewley and Li (2000) examine factors associated with the environmental disclosures in Canada from a voluntary disclosure theory perspective. The authors measure environmental disclosures by 188 Canadian manufacturing firms in their 1993 annual reports using the Wiseman index. A firm’s pollution propensity (i.e., environmental performance) is proxied by their industry membership and by whether they report to the Ministry of Environment under the National Pollution Release Inventory program. The study finds that firms with more news media coverage of their environmental exposure, higher pollution propensity, and more political exposure are more likely to disclose general environmental information, suggesting a negative association between environmental disclosures and environmental performance.Belal (2001) surveyed CSR disclosure practices in Bangladesh. Imam found that the level of such disclosures was very poor and inadequate. Belal examined the annual reports of 30 companies listed on the Dhaka Stock Exchange. He found that though 97 percent of companies made some form of CSR disclosure, the volume disclosed was very low. The disclosures were largely descriptive in nature, and emphasized ‘good news’. Only one instance of ‘bad news’ disclosure was found (Belal, 2001). Sarumpaet (2005) using a sample size of 252 listed companies in Indonesia, investigated the relationship between financial performance and environmental reporting. It concluded that that financial performance had no significant relationship with environmental performance. Other studies by Fiori, Donato & Izzo (2008), Teresa (2006), and Hull & Rothenberg (2009) consistently found no statistical relationship between financial leverage voluntary environmental disclosures. They opined that the financial health profile of a company to a large extent will determine the extent to which corporate environmental disclosure.

4. Theoretical Framework

- Stakeholders TheoryFreeman and Reed (1983) have identified stakeholders as “the groups who have an interest in the actions of the corporation. In a follow up study, Freeman (1984) revisited stakeholder theory and redefined stakeholders as any individual or group who has an interest in the firm because he (or she) can affect or is affect by the firms activities. Carroll (1999) has defined stakeholders as any individual or group who can affect or is affected by the actions, decisions, policies, practices, or goal of the organization. Stakeholders can be identified by the legitimacy of their claims which is substantiated by a relationship of exchange between themselves and the organization, and hence stakeholders include stockholders, creditors, managers, employees, customers, suppliers, local communities and the general public. Stakeholder theory suggest than an organization will respond to the concerns and expectations of powerful stakeholders and some of the response will be in the form of strategic disclosures Stakeholders theory provides rich insights into the factors that motivate managerial behaviour in relation to the social and environmental disclosure practices of organizations. Previous social and environmental accounting research which utilized these theories indicate that organizations respond to the expectations of stakeholders groups specifically and generally to those of the broader community in which they operate, through the provision of social and environmental information within annual reports.

5. Methodology

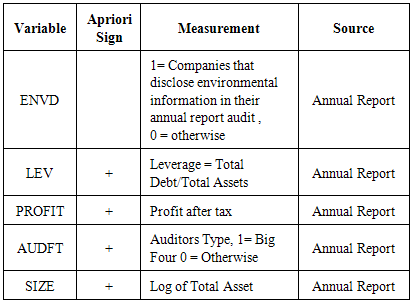

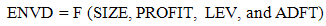

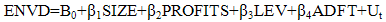

- The design adopted for the study was the cross-sectional research design. The population of the study covers all companies quoted on the Nigerian stock exchange as at the study period. However, resulting from the practical difficulties of accessing the population, a subset regarded as a sample will be utilized. The basis for sampling is justified by the law of statistical regularity which holds that on the average a sample selected from a given population will exhibit the properties of its source (Green, 2003). The simple random sampling technique was employed in selecting 15 companies from the oil and gas sectors for 2008 – 2013 financial years. Secondary data was be used for the study. The secondary data was be retrieved from financial statements of the sampled companies. A binary regression method was adopted as the data analysis method. Binary regressions have the objective of obtaining a functional relationship between a transformed qualitative variable called logit or probit and the predictor variables which can either be quantitative or qualitative. The choice of binary regression models (probit, and logit regression) to relate the explanatory variables to the probability of a firm’s willingness to report environmental information was based on the limited nature of the dependent variable and the inability of the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) multiple regression model to yield reliable coefficients and inference statistics in situation where the dependent variable is binary (0 and 1). The binary regression models unlike others is based on the use of dichotomous dependent variable, in which an observation scores one(1) if it is present and zero(0) if it is otherwise. The study adopted the two widely used binary regression models (Logit and Probit). The difference in these models is based on the type of probability distribution they assume. Logistic binary regression follows a cumulative logistic probability distribution while the binary probit assumes cumulative normal distribution. Model SpecificationThe model for the study is specified thus;

| (1) |

| (2) |

|

|

6. Data Presentation and Analysis

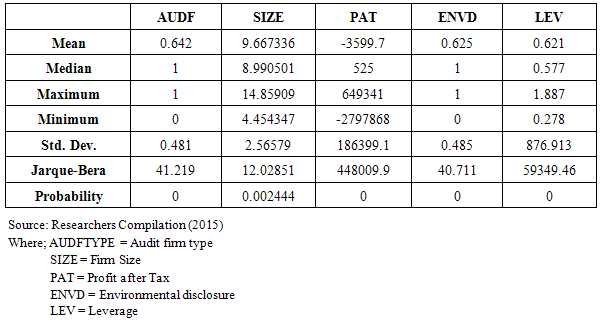

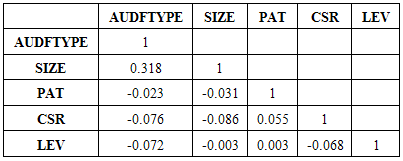

- From the descriptive statistics of the variables as shown in table 2 above, the mean value for Auditor Type (AUDTYP) is 0.642 and this shows that about 64.2% of the companies in the study employ the services of the Big four audit firms in Nigeria. The standard deviation stood at 0.481 which again indicates the existence of strong clustering of the sample in this case in relation to the average auditor type decision. The Jarque-Bera-statistic of 41.219 and the p-value of 0.00 indicate that the distribution indicate that the distribution is normal at 5% level of significance (p<0.05). The mean for Company Size measured as the log of total assets stood at 9.667 with maximum and minimum values of 14.859 and 4.454 respectively. The standard deviation of 2.566 shows evidence of considerable clustering of firm size around the mean indicating that the sizes of the companies in the sample may not be significantly different from the mean size. The Jacque-Bera of the statistic of 12.029 and p-value of 0.00 indicates that the data is normal and that outliers are unlikely in the series. In addition, it is observed that Profit after Pat (PAT) as a mean value of 35999.7 with maximum and minimum values of 649341 and -2797868 respectively. The standard deviation measuring the spread of the distribution stood is 186399.1 is large and implies that the profitability levels for the firms differ significantly from the average. The Jarque-Bera-statistic stood at 448009.9 with a p-value of 0.00 which suggest that the data satisfies normality at 5% level of significance (p<0.05). The mean value for environmental disclosure stood at 0.625 which indicates that about 62.5% of the companies in the sample engage in Environmental disclose. The standard deviation stood at 0.485 indicates the existence of strong clustering of the distribution about the mean. The Jarque-Bera-statistic of 40.711 and the p-value of 0.00 indicate that the distribution passes the normality test at 5% level (p<0.05). Finally, Leverage is observed with a mean value of 0.62 with maximum and minimum values of 1.88 and 0.278 respectively. The standard deviation value of 0.29 indicates strong clustering around the mean. The Jarque-Bera statistics of 59349.46 and p value of 0.00 indicates that the series satisfies the normality criterion and that selection bias is unlikely in the sample. Next, we shall examine the correlation results. Table 3 shows the Pearson correlation coefficient result for the variables. As observed, AUDFTYPE (Audit firm type) appear to be positively correlated with Firm SIZE (0.318). PAT shows negative correlation with AUDFTYPE (-0.023), with ENVD (-0.076) and with LEV (-0.072) while SIZE appears to be negatively correlated with ENVD (-0.086) and with LEV (-0.003). PAT is observed to be positively correlated with ENVD (0.055) and with LEV (0.003). Finally, ENVD and LEV are observed to be correlate negatively (-0.068). The correlation coefficient results show that none of the variables are very strongly correlated and this indicates that the problem of multicollinearity is unlikely and hence the variables are suitable for conducting regression analysis.

|

|

7. Discussion of Findings

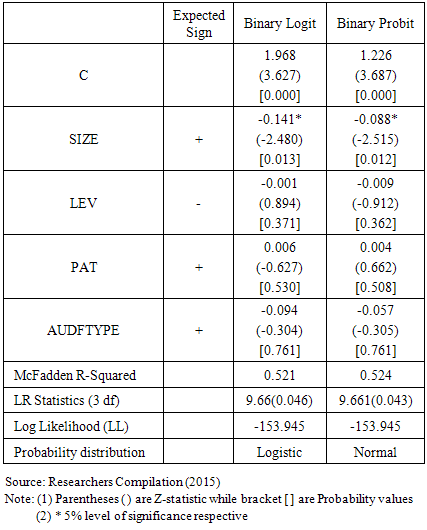

- The study finding reveals that firm size impacts negatively and significantly on the decision to disclose environmental information by quoted companies and the result is also significant at 5%. Our finding especially with regards to the significance of company size is consistent with Hackson and Milne (1996), Belkaoui and Karpik, (1989) Trotman and Bradley, (1981) Adams and Hart, (1998). However, Singh and Ahuja (1983) find no significant relationship between size and Social responsibility reporting. However, with regards to the direction of the relationship, a variance is observed between our finding and certain arguments in extant literature. Singhvi and Desai, (1971) Firth (1979) argue that small firms are more likely to hide crucial information because of their competitive disadvantage within their industry. Using the political cost approach, the argument is that large firms are more willing to be environmentally responsible to reduce their political cost. Since their higher visibility can easily lead to more litigation and governmental intervention. In addition, larger firms tend to have more experiencing dealing with multiple stakeholder pressures and have become adopt at handling the need for a “greener” business perspective. According to Hackson and Milne (1996) both agency theory and legitimacy theory also contain arguments for a size disclosure relationship. Also, larger companies have more shareholders who might be interested in social and environmental disclosure. Also, we find that Leverage appears to have a negative on the decision to disclose environmental information by quoted companies although the relationship is not significant. The non-significance of the relationship as found in this study is in line with the findings of Chow & Wong-Boren (1987), Ahmed & Nicolls (1994) and Mohamed & Tamoi (2006) which found no statistical relationship between financial leverage and voluntary corporate social responsibility disclosure. According to Healy and Palepu (1995), leverage may be determinant of voluntary environmental reporting as firms may need to resolve asymmetric information and agency problems with the stakeholders. Profit after tax appears to have a positive impact on the decision to disclose environmental information by quoted companies. Although the result is not significant, it nevertheless suggests that economic performance of a firm affects management’s decision to behave in a way that may be termed socially responsible. The argument is that activities of relating to environmental disclosures no doubt constitute a cost burden on firms. Therefore, when companies are doing well they could most likely have the means to engage in environmental disclosures. However, when companies are financially not performing well, economic demand take precedence over social and environmental performance. However, the non-statistical significance of the variable as found in this study seems to be in line with Ingram & Frazier (1980), King and Lenox, (2001) Suttipun and Stanton (2012) but is in contrast with Russo and fouts (1997) and Islam (2010). Audit firm type appears to have a negative but not significant impact on the decision to disclose environmental information by quoted companies although the result is not significant at 5%. Jensen and Meckling (1976), Watts (1977) and Watts and Zimmerman (1990) argue that auditors incur costs from entering contracts with audit clients, and so will influence clients to disclose as much information as possible in their annual reports. Auditors with high reputation such as the Big Four are less likely to be associated with clients that disclose low levels of information in their published annual reports. Nevertheless, empirical studies that examine the relation between the size of audit firms and the extent of voluntary disclosure by companies are contradictory. Craswell and Taylor (1992) found a positive relationship between auditor and voluntary reserve disclosure in the Australian oil and gas industry, while Malone et al. (1993) found no significant statistical relation between auditor and voluntary reserve disclosure in the United States oil and gas industry. A study done by Tan, Kidman and Cheong (1990) also found no support that audit firms influence disclosure strategies of companies.

8. Conclusions

- Corporate social and environmental responsibility is a company’s commitment to operating in an economically, socially and environmentally sustainable manner whilst balancing the interests of diverse stakeholders. Corporate social and environmental reporting represents the private sector’s way of integrating the economic, social, and environmental imperatives of its activities. Corporate social and environmental reporting has attracted much attention over the past three decades. However, Managers tend to weigh the benefits and costs of disclosing environmental information. The study provides insight into the determinants of corporate social reporting decision. In this regards firm size impacts negatively and significantly on the decision to disclose corporate social responsibility by quoted companies and the result is also significant at 5%. Leverage appears to have a negative impact on the decision to disclose environmental information by quoted companies although the relationship is not significant. Profit after tax appears to have a positive impact on the decision to disclose environmental information by quoted companies although the result is not significant at 5%. Audit firm type appears to have a negative but not significant impact on the decision to disclose environmental information by quoted companies. Although the result is not significant at 5%. The study recommends the following; Firstly, there is a need for corporate entities to improve their environmental responsibility practices and disclose comprehensively their environmental risks, liabilities and impact on the environment. The voluntary stance of environmental reporting has often be used as a cliché for companies to under report their effect on the environment and this is responsible for the negligence of several corporate entities with regards to environmental reporting. We suggest that incentives be put in place to motivate disclosures. For example in several developed economies, environmental disclosures have been listed as part of the requirements for listing on the stock exchange.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML