-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2015; 4(1): 79-107

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20150401.08

A Cash-Flow Theory of Stock Valuation

Randa I. Sharafeddine

Finance Department, Lebanese International University, Lebanon

Correspondence to: Randa I. Sharafeddine, Finance Department, Lebanese International University, Lebanon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This article introduces a theory of stock valuation based on cash-flow analysis to price stocks, where the cash receipts and the cash payments of the firm is projected for each time period for ever where a continuous adjustment of the variables affecting the discounted present value of the cash-flow stream will show its effect on the value of the company’s stock. Not only does this starting point by-pass certain measurement problems, but it also direct attention to the relevant variables in a manner that other approaches may not. The financial manager is now required to generate a cash-flow net not only to satisfy the explicit cost but also the implicit cost of the providers of funds in order to create value. And to determine the optimal cash balance that minimizes the opportunity cost and maximizes shareholders’ wealth.

Keywords: Invested Capital, Net Cash-Flow, Shareholder Value Added, Economic Profit, Accounting Profit, Business Profit, Pure Profit, Working Capital Requirements, Economic Value Added

Cite this paper: Randa I. Sharafeddine, A Cash-Flow Theory of Stock Valuation, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 4 No. 1, 2015, pp. 79-107. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20150401.08.

Article Outline

1. Purpose

- The purpose of this study is to show that the whole financial system is becoming a Cash-flow system where a continuous adjustment of the variables affecting the discounted present value of the cash-flow stream will show its effect on the value of the company’s stock. Our Financial System would react to the cash-flow and corporation reacts to what investors react and vice versa. All investors operate on time value of money. From here rises a cash flow concept of profit associated with the cash-flow theory of stock valuation.This theory of stock valuation is based on the assumption that the cash receipts and the cash payments of the firm have been projected for each time period for ever. So, we should live day per day this reality in order to operate in the future. And the whole financial system would become a Cash-flow system where a continuous adjustment on hour per hour, day per day of the variables affecting the discounted present value of the cash-flow stream will show its effect on the value of the company’s stock.A careful definition of cash flows and a theory of stock pricing based on cash-flow analysis is required because previous discussions have been concerned with investment decisions rather than stock pricing. They have therefore been concerned with the cash flow associated with a particular investment project, rather than with the flows to the firm as a whole, and we must recognize the possibility that cash flows generated by one project will be used to finance another project.This Cash Flow Concept of Stock valuation also implies that a decision to undertake investment projects in the future influences the value of the stock today. The stock value is based entirely upon future cash flows, and it makes no difference whether the flows are expected in connection with a project that has already been undertaken or a project that is going to be undertaken in the future. It makes no difference that is unless the cash flows associated with future projects are considered to be more risky than those associated with current projects. As a financial manager in his decision making that would maximize the market value of its securities should respond to the investor behaviour, who as a rational trader will manage his economic asset so as to maximize the satisfaction he derives from them. Under the article of Friedman and Savage “The Utility Analysis of Choices Involving Risk”, the consumer unit will choose the income to which he attaches the most utility. A rational investor will try to maximize the monetary value of the assets he owns. From this interpretation of income and value follow the broad outlines of modern financial theory. Investors will be faced with a trade-off between risk and return and as we don’t have homogeneous investors, their expectation may also vary affecting the value of the stock in the firm. So, this trade off would become the central problem of Finance.In the business we don’t talk anymore about net income but about net cash-flows. The concept of profit is different from the conventional concept called “Earnings”, the word “profit” can be reversed for the cash flow concept. Earnings of a period are associated with the difference between the sales value and the cost of production of the goods sold during the period. Earnings are not influenced by changed expectations about the future as profits are. There have been a number of attempts to test whether investors are myopic. For example, McConnell and Muscarella examined the reaction of stock prices to announcements of capital expenditure plans. If investors were interested in short-term earnings, which are generally depressed by major capital expenditure programs, then these announcements should depress stock prices. But they found that increases in capital spending were associated with increases in stock prices and reductions were associated with falls. Similarly, Jarrell, Lehn, and Marr found that announcements of expended R&D spending prompted arise in the stock price. See J. McConnell and C. Muscarella, “Corporate Capital Expenditure Decisions and the Market Value of the Firm,” Journal of Finanacial Economics, 14:399-422 (July 1985), and G. Jarrell, K. Lehn, and W. Marr, “Institutional Ownership, Tender Offers, and Long-term Investments,” The Office of the Chief Economist, Securities and Exchange Commission (April 1985). Despite the fact that according to Modigliani and Miller the value of the firm is determined on the left-hand side of the balance sheet by real assets and not by the proportions of debt and equity securities issued by the firm or its capital structure, this was subsequently subjected to empirical testing by Durand and shown to be invalid. So, according to MM a firm cannot change the total value of its securities just by splitting its cash-flows into different streams. Modigliani and Miller argued that the value of the firm is determined only by its basic earnings power and its business risk, so a firm’s basic resource is the stream of cash-flows produced by its real assets and not by the securities it issues or on how this income is split between dividends and retained earnings, when the firm is financed entirely by common stock, all those cash-flows belong to the stockholders, when the firm issues both debt and equity securities, the cash-flows is divided between debtholders and stockholders. However, in our study we should state a linkage between firm value and earnings, which would affect the optimal leverage decision.Although the problem that confronts us can be approached in a variety of ways, our preference is to commence with net cash flows from operations and to consider the effect of additions to, and subtractions from, these flows upon stock values. Not only does this starting point by-pass certain measurement problems, but it also direct attention to the relevant variables in a manner that other approaches may not.Net cash-flows from operations are available for (1) the payment of interest and principal on debt or the equivalent and (2) capital expenditures and dividend payments. Operating cash-flows can of course, be supplemented in any period by debt or equity financing. Debt financing creates obligations to pay out cash in future periods and thereby reduces cash flows available for capital expenditures and dividends in those periods. Equity financing, in turn diminishes the pro rata share of total cash-flows available for dividends and reinvestment. The issue becomes one of dividing the stream of operating cash-flows among debt, dividends and reinvestment and it may no longer be feasible to assume that the size and shape of the stream of operating cash-flows is independent of the manner in which it is subdivided.Though capital structure decisions are influenced by a firm’s ability to generate future cash flows, the theoretical literature has neglected the dynamic relation between leverage and firm specific earnings behaviour. HOWEVER, with the cash-flow theory of stock valuation, under a theory of continuous time, we have adjustments in the business (capital) structure, policy and optimality on hour per hour and day per day basis in order to avoid the risk inherent in the capital structure of the business. We will use the article of Steven Raymar “A Model of Capital Structure when Earnings are Mean-Reverting” to give a clear meaning to a theory of continuous time. Raymar assumes a linkage between firm value and earnings, which would affect the optimal leverage decisions. So, leverage is reviewed and reoptimized every period and the variability of leverage is positively related to variability in earnings and firm value. EBIT follows an exogenous process that is unaffected by leverage or default. Its parameters are such that the firm never liquidates if optimal policies are followed. The autocorrelation between earnings at time t and t+1 is , if =0, earnings are serially independent, and as approaches 1 the process tends toward a random walk, implication of the process is that, while a firm may experience a bad or a good year over time, it is expected to revert to a normal performance level. An unlevered firm is valued as the discounted sum of expected future after-tax earnings, because stockholders receive the firm’s income stream in perpetuity, it must never be optimal for them to relinquish ownership, as it might be if income were negative, this would be optimal for stockholders to maintain the unlevered firm as a going concern, given any feasible earnings realization. When debt is introduced in the financing activities of the corporation, the firm is assumed to issue single period debt and to optimally recapitalize at each date. As firm optimally and continuously recapitalize, under continuous time the focus is not on conflicts of interest among claimants, because debt has a one period maturity, the optimal policy should maximize both equity and firm value, so adjustments are made on daily basis and when earnings are low, a firm should optimally reduce its leverage ratio and debt level or otherwise said reducing its cost of capital and the earnings process permits one firm to be safer than another over a short horizon. At each date, the firm is recapitalized so as to maximize the wealth of current owners. This process is costless if the firm is solvent, but otherwise the transfer of ownership and control is assumed to induce bankruptcy reorganization costs and the model is unaffected as long as a clear distinction between debt and equity remains. Default that caused liquidation in the past is now resulting in an optimal reorganization. Since an optimal debt decision needs to consider only the future cash-flows of the firm and is independent of past earnings and debt levels. Then a change in the autocorrelation between earnings at time t and t+1, also affects future debt decisions and firm values. From here rises a cash-flow concept of profit associated with the cash-flow theory of stock value.

2. The Notion of Income and Wealth

- Under the notion of income, we will differentiate between Income and wealth. We will start by giving the broad outlines of modern financial theory that follow from the interpretations of income and value; we must look at income from the shareholders’ point of view, since the criterion is the maximization of the present value of a share of stock to present stockholders.I will also try to show in this part that the discounted present value DPV approach to value and income is one facet of a more general theory of the valuation of shares in the market where value is determined by the DPV approach which is the preferable after establishing that different ways of looking at income and wealth result in substantially different ways of reporting the results of a given investment and cash-flow pattern.Income from the point of view of the shareholders of the firm may be defined as the increment in the shareholders’ personal wealth as a result of their ownership of the firm’s stock over a specified period.To trace out the implications of this definition, suppose a group of investors contributes a total of Io dollars for N shares of stock of some corporation. The total value of the company at this point is just Io. Suppose Io is invested in a project of limited life, terminating in some period t = t*. It is assumed that cash returns to this investment are paid to the shareholders as dividends, and that i is constant over time.If the investment will earn a rate of return greater than i, then Vo>Io, and there is an immediate increase in the value of the company’s stock as soon as the company is committed to the investment. This increase in value represents income. The income in year zero, Yo, would be given by Vo–Io, or, since Io is a negative cash flow, Vo +Fo. This income is a ”Windfall gain,” which accrues to the owners of the firm as a result of their being able to invest in a project that is more profitable than the standard market rate.Once the windfall gain is realized through the increase in value of the owners’ stock, income will continue to be realized at a rate of exactly i on the value of their equity for the remainder of the project’s life. It follows from the discounted present value (DPV) definition of wealth that the income of any period j is the net cash flow Fj plus the appreciation (or minus the depreciation) in value during the period.Now, a necessary condition for capital market equilibrium is that the company earn at a rate just equal to i once the windfall gains have been realized. The DPV approach to value and income is one facet of a more general theory of the valuation of shares in the market.

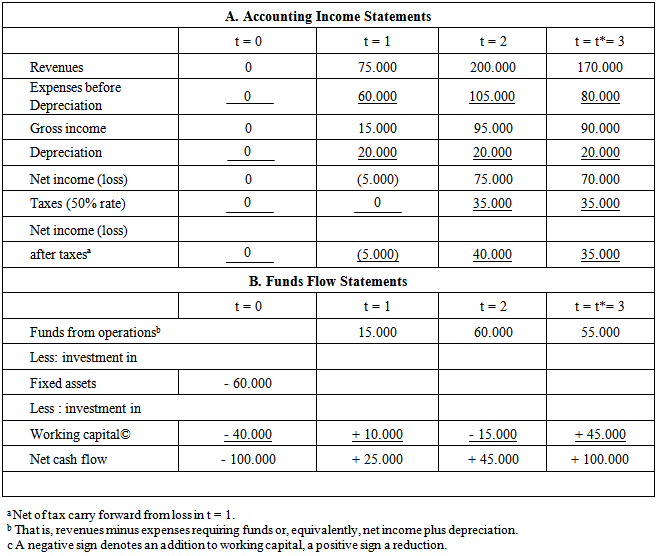

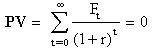

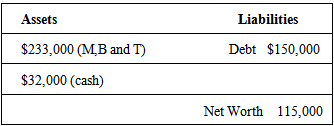

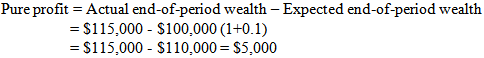

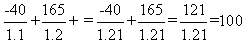

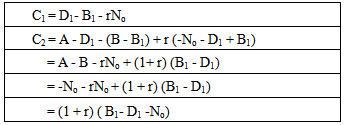

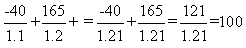

And the development of the central idea underlies a large part of this volume. Our position is that the objective of financial management should be to maximize the value of the company to present shareholders. In any case where value is determined by the DPV approach, the DPV notion of income is clearly the appropriate one. We should however, establish that different ways of looking at income and wealth result in substantially different ways of reporting the results of a given investment and cash-flow pattern. One such divergent method is the accounting process except to remark that basing income on historical data rather than expectations is antipodal to the notion of DPV- based income.Another way in which wealth as monetary value can be viewed, which has a certain common-sense appeal, is based on the internal rate of return (IRR) basis for evaluating profitability. This method defines wealth as "owner-contributed funds plus the return on these funds as the internal rate of return less withdrawal." Specifically, for the same hypothetical company investing Io, assume that the return on this investment will be r> i. Rather than working through all the implications of this notion formally, we will present a more or less realistic example of how the different interpretations of income would work out if applied to a hypothetical investment project.Assume Io consists of a total outlay of $100,000, $60,000 of this for equipment (depreciated on a straight line basis) and $40,000 for working capital. The investment project will last three years, i.e., t* = 3. The tables above labelled A and B show accounting income and funds flow for the project. It is again assumed that cash returns on this investment are paid out to stockholders and not reinvested in the firm; also, the discount rate is set at i = 0.10 or 10%.We can solve by using the following equation to obtain r = 0.25 or IRR = 25%

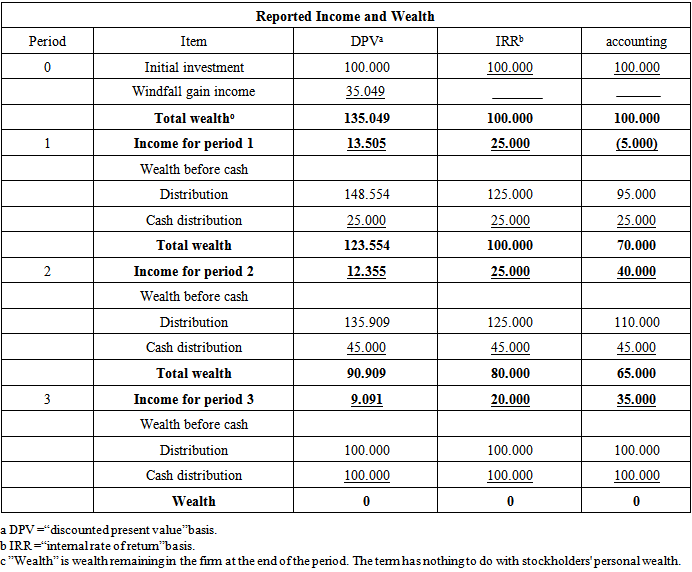

And the development of the central idea underlies a large part of this volume. Our position is that the objective of financial management should be to maximize the value of the company to present shareholders. In any case where value is determined by the DPV approach, the DPV notion of income is clearly the appropriate one. We should however, establish that different ways of looking at income and wealth result in substantially different ways of reporting the results of a given investment and cash-flow pattern. One such divergent method is the accounting process except to remark that basing income on historical data rather than expectations is antipodal to the notion of DPV- based income.Another way in which wealth as monetary value can be viewed, which has a certain common-sense appeal, is based on the internal rate of return (IRR) basis for evaluating profitability. This method defines wealth as "owner-contributed funds plus the return on these funds as the internal rate of return less withdrawal." Specifically, for the same hypothetical company investing Io, assume that the return on this investment will be r> i. Rather than working through all the implications of this notion formally, we will present a more or less realistic example of how the different interpretations of income would work out if applied to a hypothetical investment project.Assume Io consists of a total outlay of $100,000, $60,000 of this for equipment (depreciated on a straight line basis) and $40,000 for working capital. The investment project will last three years, i.e., t* = 3. The tables above labelled A and B show accounting income and funds flow for the project. It is again assumed that cash returns on this investment are paid out to stockholders and not reinvested in the firm; also, the discount rate is set at i = 0.10 or 10%.We can solve by using the following equation to obtain r = 0.25 or IRR = 25% Now, the table below sets out the figures obtained for income and wealth in period zero to period three, by applying the DPV, IRR, and accounting approaches. The DPV approach gives a windfall gain in t = 0 of $35,049 (later in my paper called pure profit); neither of the other approaches indicates that any income is realized during this period. Wealth, at the end of t = 0, is $135,049 where the DPV method is used, and $100,000 in each of the other cases. (Wealth is Vj in the DPV method, Ij in the IRR method, and the book value of equity in the accounting method).

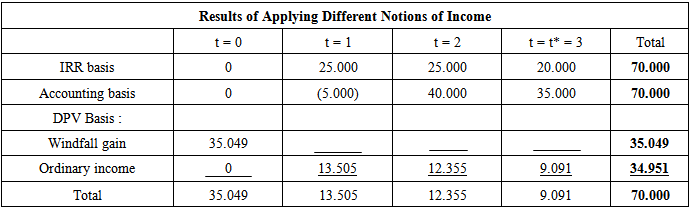

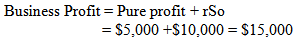

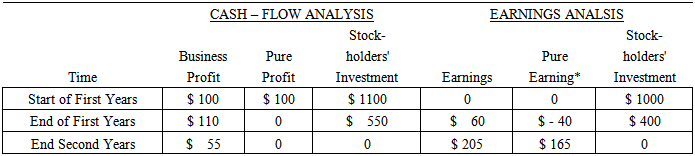

Now, the table below sets out the figures obtained for income and wealth in period zero to period three, by applying the DPV, IRR, and accounting approaches. The DPV approach gives a windfall gain in t = 0 of $35,049 (later in my paper called pure profit); neither of the other approaches indicates that any income is realized during this period. Wealth, at the end of t = 0, is $135,049 where the DPV method is used, and $100,000 in each of the other cases. (Wealth is Vj in the DPV method, Ij in the IRR method, and the book value of equity in the accounting method). Hint: Windfall gain income is the pure profit, I would explain it below under the concept of profit. For the DPV method, the reported income in period 1 is $23,505 which is 10 per cent of the wealth at the beginning of that period. Since $25,000 is paid out to the shareholders, the value at the end of period 1 must be less than at the end of period 0, that is, $ 123,554 is less than $135,049. The income in period 2 is 10 per cent of $123,554 and so on.Under the IRR approach, the wealth at the beginning of period 1 is $100,000, since the actual increase in the stockholders’ value is not reported. Income in this period is figured at 25 per cent of wealth, or $25,000. By chance, exactly this amount is paid out. Income in period 2 is 25 per cent of the remaining wealth, again $25,000, but in this case $45,000 is paid out, leaving a smaller base for period 3 income.The accounting approach warns of a substantial loss in period 1, the accounting figures indicate substantially higher income in later periods.HINT: Under the DPV approach as more and more of the project’s returns are paid out, the value of the stock declines, and consequently the income earned by the firm declines (even though the stockholders’ personal wealth may be continually increasing). Income figures obtained by other methods, however, do not follow this pattern and as a consequence, are not related in any simple way to the value of the firm’s stock.The table below summarizes the income reported by the three methods. It will be noted that the total income reported over the three-year period is the same in every case only the timing of the reported income differs.

Hint: Windfall gain income is the pure profit, I would explain it below under the concept of profit. For the DPV method, the reported income in period 1 is $23,505 which is 10 per cent of the wealth at the beginning of that period. Since $25,000 is paid out to the shareholders, the value at the end of period 1 must be less than at the end of period 0, that is, $ 123,554 is less than $135,049. The income in period 2 is 10 per cent of $123,554 and so on.Under the IRR approach, the wealth at the beginning of period 1 is $100,000, since the actual increase in the stockholders’ value is not reported. Income in this period is figured at 25 per cent of wealth, or $25,000. By chance, exactly this amount is paid out. Income in period 2 is 25 per cent of the remaining wealth, again $25,000, but in this case $45,000 is paid out, leaving a smaller base for period 3 income.The accounting approach warns of a substantial loss in period 1, the accounting figures indicate substantially higher income in later periods.HINT: Under the DPV approach as more and more of the project’s returns are paid out, the value of the stock declines, and consequently the income earned by the firm declines (even though the stockholders’ personal wealth may be continually increasing). Income figures obtained by other methods, however, do not follow this pattern and as a consequence, are not related in any simple way to the value of the firm’s stock.The table below summarizes the income reported by the three methods. It will be noted that the total income reported over the three-year period is the same in every case only the timing of the reported income differs.  This is not to say that alternate concepts of income may not be useful or necessary or both, but we must look at income from the shareholders’ point of view. This is the basic reason why the DPV approach is preferable.

This is not to say that alternate concepts of income may not be useful or necessary or both, but we must look at income from the shareholders’ point of view. This is the basic reason why the DPV approach is preferable.3. A Theory of Cash-Flow

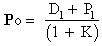

- The Link between Stock Price and Net Cash-Flow:A Cash-flow theory says that the value of the stock is the present value of the future net cash flows. And this Net Cash-Flow is the cash-flow between the firm and its stockholders. A positive net cash-flow represents a cash payment by the firm to the stockholders, while a negative net cash-flow represents a cash payment by the stockholders to the firm.Example 1Before going further in explaining the concept of “Cash-Flow Concept of Stock Valuation”, I would like to introduce a small example related to “Dividend Policy and Value” where I would show that the total value of the company depend on the Net Cash-flow between the firm and its stockholders and not on dividend :First:We already know that the value of a share of stock is established as the present value of all future dividends:

Second:Assume that additional capital investment will be made at time one, but that all earnings will be paid out as dividends after that time. Then the value of a share of stock at time one is:

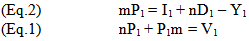

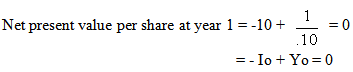

Second:Assume that additional capital investment will be made at time one, but that all earnings will be paid out as dividends after that time. Then the value of a share of stock at time one is: V1 is the value of the firm at time onen is the number of shares outstanding at time zerom is the number of shares that must be issued at time one to raise capital for predetermined new investments.Then:

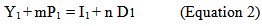

V1 is the value of the firm at time onen is the number of shares outstanding at time zerom is the number of shares that must be issued at time one to raise capital for predetermined new investments.Then: I1 is the amount of new equity required for capital investment at time one, so I1 = mP1, is a flow of cash from the stockholders to the firm. Y1 is the amount of income at time one, and as all earnings are paid as dividends, so Y1 = n D1, is a flow of cash from the firm to the stockholders. Then,

I1 is the amount of new equity required for capital investment at time one, so I1 = mP1, is a flow of cash from the stockholders to the firm. Y1 is the amount of income at time one, and as all earnings are paid as dividends, so Y1 = n D1, is a flow of cash from the firm to the stockholders. Then, If we substitute eq. 2 in eq. 1 we have the following:nP1 + (I1 + nD1 – Y1) = V1nP1 + nD1 = V1 – I1 + Y1This equivalent to say P1 = [(V1 – I1 + Y1) / n] – D1Substituting P1 in the following Equation: Po = (P1 + D1) / 1 + KPo = 【 [(V1 –I1 + Y1) / n] – D1 + D1】/ 1 + KSimplifying Po = [(V1 – I1 + Y1) / n] / 1 + KV1 is the present value at time one, predetermined set of investment.I1 is the amount of new equity required for capital investment at time one, a flow of cash from the stockholders to the firm. A negative sign.Y1 is the amount of income available at time one, a flow of cash from the firm to the stockholders. A positive sign.n is the number of shares outstanding at time zero.K is the required return for investment of this risk level.The important thing to note is that dividends have disappeared ; the value of a share of stock have been defined by the net cash-flows determined as the flows between the firm and its stockholders, and that the Gordon Model used to find the value of a constant growth stock has become a cash-Flow theory of stock valuation.These flows are not changed by the decision to finance internally or to issue new stock. If the stockholders receive a dividend of $1 million, this is a net cash-flow of plus $1 million. If $1 million of new stock is sold, this is a net cash flow of minus $1 million. If both transactions take place in the same period, the net cash-flow is the sum of the two, or zero. This is exactly what the net cash-flow would be if no dividends were paid, no new stock was issued, and the project was financed internally.From here rises the cash-flow profit of stock valuation defined as the increase (decrease) in the stock value V1 plus the net cash-flow for the period (-I1 + Y1).Example 2Let us take another example to clarify and stress the cash flow concept of stock valuation, and let us make a shift from what was traditionally acceptable, “link between stock price and earnings “to “a link between stock price and cash-flows”.This example is from the book of Brealy and Myers titled “Principles of Corporate Finance” chapter four.Imagine the case of a company that does no grow at all. It does not plow back any earnings and simply produces a constant stream of dividends. Its stock would be rather like the perpetual bond and the return on perpetuity is equal to the yearly cash-flow divided by the present value. The expected return on our share would thus be equal to the yearly dividend divided by the share price (i.e., the dividend yield). Since all the earnings are paid out as dividend, the expected return is also equal to the earnings per share divided by the share price (i.e., the earnings-price ratio). For example, if the dividend is $10 a share and the stock price is $ 100, we have:Expected return = Dividend yield = Earnings-price ratio

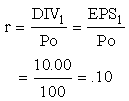

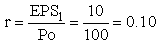

If we substitute eq. 2 in eq. 1 we have the following:nP1 + (I1 + nD1 – Y1) = V1nP1 + nD1 = V1 – I1 + Y1This equivalent to say P1 = [(V1 – I1 + Y1) / n] – D1Substituting P1 in the following Equation: Po = (P1 + D1) / 1 + KPo = 【 [(V1 –I1 + Y1) / n] – D1 + D1】/ 1 + KSimplifying Po = [(V1 – I1 + Y1) / n] / 1 + KV1 is the present value at time one, predetermined set of investment.I1 is the amount of new equity required for capital investment at time one, a flow of cash from the stockholders to the firm. A negative sign.Y1 is the amount of income available at time one, a flow of cash from the firm to the stockholders. A positive sign.n is the number of shares outstanding at time zero.K is the required return for investment of this risk level.The important thing to note is that dividends have disappeared ; the value of a share of stock have been defined by the net cash-flows determined as the flows between the firm and its stockholders, and that the Gordon Model used to find the value of a constant growth stock has become a cash-Flow theory of stock valuation.These flows are not changed by the decision to finance internally or to issue new stock. If the stockholders receive a dividend of $1 million, this is a net cash-flow of plus $1 million. If $1 million of new stock is sold, this is a net cash flow of minus $1 million. If both transactions take place in the same period, the net cash-flow is the sum of the two, or zero. This is exactly what the net cash-flow would be if no dividends were paid, no new stock was issued, and the project was financed internally.From here rises the cash-flow profit of stock valuation defined as the increase (decrease) in the stock value V1 plus the net cash-flow for the period (-I1 + Y1).Example 2Let us take another example to clarify and stress the cash flow concept of stock valuation, and let us make a shift from what was traditionally acceptable, “link between stock price and earnings “to “a link between stock price and cash-flows”.This example is from the book of Brealy and Myers titled “Principles of Corporate Finance” chapter four.Imagine the case of a company that does no grow at all. It does not plow back any earnings and simply produces a constant stream of dividends. Its stock would be rather like the perpetual bond and the return on perpetuity is equal to the yearly cash-flow divided by the present value. The expected return on our share would thus be equal to the yearly dividend divided by the share price (i.e., the dividend yield). Since all the earnings are paid out as dividend, the expected return is also equal to the earnings per share divided by the share price (i.e., the earnings-price ratio). For example, if the dividend is $10 a share and the stock price is $ 100, we have:Expected return = Dividend yield = Earnings-price ratio  The price equals

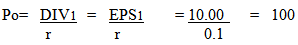

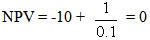

The price equals The expected return for growing firms can also equal the earnings-price ratio. The key is whether earnings are reinvested to provide a return greater or less than the market capitalization rate. For example, suppose our monotonous company suddenly hears of an opportunity to invest $10 a share next year. This would mean no dividend at t=1. However, the company expects that in each subsequent year the project would earn $1 per share, so that the dividend could be increased to $11 a share.Let us assume that this investment opportunity has about the same risk as the existing business. Then we can discount its cash flow at the 10 percent rate to find its net present value at year 1:

The expected return for growing firms can also equal the earnings-price ratio. The key is whether earnings are reinvested to provide a return greater or less than the market capitalization rate. For example, suppose our monotonous company suddenly hears of an opportunity to invest $10 a share next year. This would mean no dividend at t=1. However, the company expects that in each subsequent year the project would earn $1 per share, so that the dividend could be increased to $11 a share.Let us assume that this investment opportunity has about the same risk as the existing business. Then we can discount its cash flow at the 10 percent rate to find its net present value at year 1: What effect will the decision to undertake the project have on the company’s share price? Clearly none.This could be explained in two different ways:First: Trough a Link between stock price and Net Cash-FlowsSecond: Trough a Link between stock price and EarningsFirst: To explain the effect of the investment on the valuation of the firm according to the Net Cash-Flow Theory defined as the cash-flows between the firm and its stockholders for the period (- Io + Yo).In our equation:

What effect will the decision to undertake the project have on the company’s share price? Clearly none.This could be explained in two different ways:First: Trough a Link between stock price and Net Cash-FlowsSecond: Trough a Link between stock price and EarningsFirst: To explain the effect of the investment on the valuation of the firm according to the Net Cash-Flow Theory defined as the cash-flows between the firm and its stockholders for the period (- Io + Yo).In our equation:

is the capital investment to undertake the project, a flow of cash from the stockholders to the firm, a negative sign.

is the capital investment to undertake the project, a flow of cash from the stockholders to the firm, a negative sign. is the amount of income the project would earn at time one discounted to time zero, a flow of cash from the firm to the stockholders, a positive sign.The Net Cash-Flow is the sum of the two, or zero, this is exactly what will be the effect on the stock valuation.Second: To explain the effect of the investment on the value of the firm according to the Earnings valuation. Brealy and Myers in their book said:The investment opportunity will make no contribution to the company’s value because its prospective return is equal to the opportunity cost of capital. The reduction in value caused by the nil dividends in year one is exactly offset by the increase in value caused by the extra dividends in later years. Therefore, once again the market capitalization rate equals the earnings-price ratio:

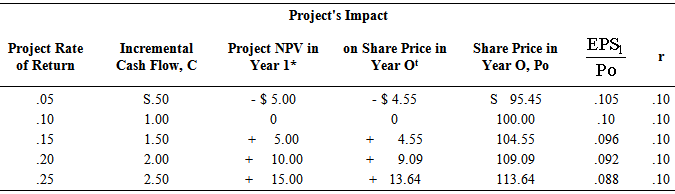

is the amount of income the project would earn at time one discounted to time zero, a flow of cash from the firm to the stockholders, a positive sign.The Net Cash-Flow is the sum of the two, or zero, this is exactly what will be the effect on the stock valuation.Second: To explain the effect of the investment on the value of the firm according to the Earnings valuation. Brealy and Myers in their book said:The investment opportunity will make no contribution to the company’s value because its prospective return is equal to the opportunity cost of capital. The reduction in value caused by the nil dividends in year one is exactly offset by the increase in value caused by the extra dividends in later years. Therefore, once again the market capitalization rate equals the earnings-price ratio:  The table below repeats our example for different assumptions about the cash-flow generated by the new project. Note that the earnings-price ratio, measured in terms of EPS1, next year’s expected earnings, equals the market capitalization rate r only when the new project’s NPV = 0. This is an extremely important point; managers frequently make poor financial decisions because they confuse earnings-price ratios with the market capitalization rate.Effects on stock price of investing an additional $10 in year 1 at different rates of return. Notice that the earnings-price ratio overestimates r when the project has negative NPV and underestimates it when the project has positive NPV.

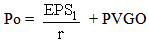

The table below repeats our example for different assumptions about the cash-flow generated by the new project. Note that the earnings-price ratio, measured in terms of EPS1, next year’s expected earnings, equals the market capitalization rate r only when the new project’s NPV = 0. This is an extremely important point; managers frequently make poor financial decisions because they confuse earnings-price ratios with the market capitalization rate.Effects on stock price of investing an additional $10 in year 1 at different rates of return. Notice that the earnings-price ratio overestimates r when the project has negative NPV and underestimates it when the project has positive NPV. In our last example both dividends and earnings were expected to grow at 10 percent, but this growth made no net contribution to the stock price. Be careful not to equate firm performance with the growth in earnings per share. A company that reinvests earnings at below the market capitalizations rate may increase earnings but will certainly reduce the share value.In general, Brealy and Myers said in their book “Principle of Corporate Finance” That we can think of stock price as the capitalized value of average earnings under a no-growth policy, plus PVGO, the present value of growth opportunities:

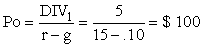

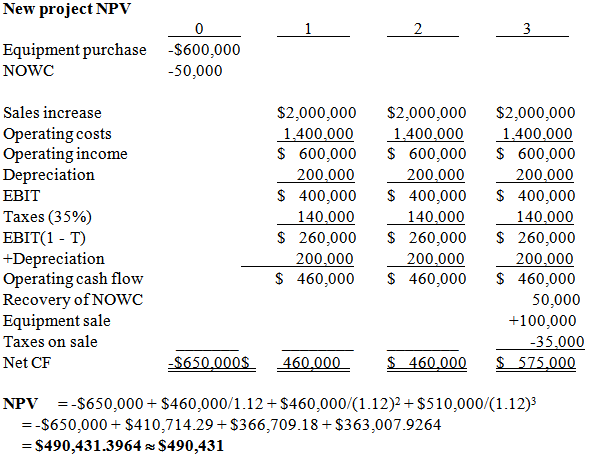

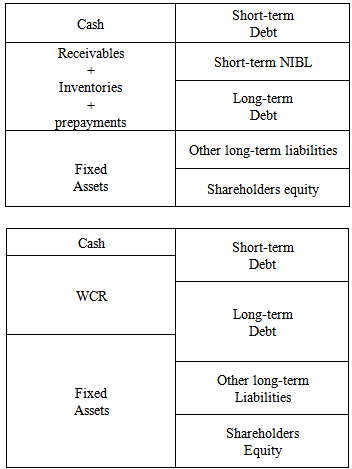

In our last example both dividends and earnings were expected to grow at 10 percent, but this growth made no net contribution to the stock price. Be careful not to equate firm performance with the growth in earnings per share. A company that reinvests earnings at below the market capitalizations rate may increase earnings but will certainly reduce the share value.In general, Brealy and Myers said in their book “Principle of Corporate Finance” That we can think of stock price as the capitalized value of average earnings under a no-growth policy, plus PVGO, the present value of growth opportunities: The important thing to note here is that:The first part of the equation is nothing than the discounted cash balance (V1) which will give its effect on the value of the stock.The second components (PVGO) is nothing then the pure profit defined as the return in excess of the normal discount rate on invested capital (-Io + Y1). So, under the Cash-Flow Theory of Stock Valuation, the price of the stock is determined by two components:The First Component:The first component is the present value of the future net cash-flows. Where management should project the future cash receipts and cash payments of the firm with various cash balances, subtract the payment from the receipts to determine net cash-flows, and then select that cash balance (i.e., purchase that amount of liquidity) which maximizes the present value of the net cash flows.In a world of certainty it would be unprofitable for a firm to hold cash. Any cash not needed immediately to make payments would be lent at interest, as liquidity is worthless if all future cash needs can be perfectly foreseen, and there are no flotation costs associated with lending, borrowing or repaying money. In the presence of uncertainty, cash balances are held because they provide liquidity. In principle, the decision to purchase liquidity by increasing cash balances or to sell liquidity by reducing cash balances should be analysed in the same way any other investment decision is analysed. An increase in cash balances is therefore considered as a purchase of liquidity and is defined as a cash payment. A reduction in cash balances is a sale of liquidity and is defined as a cash receipt. If a firm receives cash from the sale of a product and increases its bank balance, this involves both a cash receipt and a cash payment, so that the net cash flow is zero. Subsequently, when the firm reduces its bank balance to pay wages, this is again both a cash receipt and a cash payment, with a net cash-flow of zero The net cash-flow in any period therefore is the difference between cash received by the firm from purchasers, debtors, or banks, and the cash used by the firm to increase cash balances, to pay for goods and services, to pay interest or repay debt, or to lend and such flows must be associated with equity valuation.We could exclude all dealings in the firm’s financial obligations from the cash receipts and payments. The net-cash flow would then include transactions with debtholders as well as stockholders. The present value of the net cash flows would be the total value of all the firm’s financial obligations, and the value of the stock would be the total value of the obligations less the value of the debt. And this would provide the justification for the treatment of cash balances. cash balances are held because they provide liquidity. In principle, the decision to purchase liquidity by increasing cash balances or to sell liquidity by reducing cash balances should be analysed in the same way any other (investment) decision is analysed. HINT: Management should project the future cash receipts and cash payments of the firm with various cash balances, subtract the payments from the receipts to determine net cash-flows, and then select that cash balances (i.e., purchase that amount of liquidity) which maximizes the present value of the net cash flow. The net cash flow in any period therefore is the difference between cash received by the firm from purchasers, debtors, or banks, and the cash used by the firm to increase cash balances, to pay for goods and services, to pay interest or repay debt, or to lend. Such flows must be associated with equity obligations, i.e., the net cash flow is the cash flow between the firm and its stockholders. A positive net cash flow represents a cash payment by the firm to the stockholders, i.e., a dividend payment or a stock repurchase, while a negative net cash flow represents a cash payment by the stockholders to the firm, i.e., a new stock subscription.The associated theory of stock valuation is based on the assumption that the cash receipts and the cash payments of the firm have been projected for each time period for ever. We assume that there are no transaction or flotation costs, or any costs other than interest (or dividends) involved in borrowing or repaying money, or in buying or selling financial obligations. We also assume that stockholders are indifferent between capital gains and dividend income, so that we would ignore problems which arise because of the different taxes on income and capital gains. The net cash-flow would then include transactions with debtholders as well stockholders. The present value of the net cash flows would be the total value of all the firm’s financial obligations, and the value of the stock would be the total value of the obligations less the value of the debt. So, that the present value of the net cash flows is the value of the stock. Since the peculiar treatment of cash balances does not arise in evaluating any decision except the decision about the level of cash balances themselves, our treatment of cash balances does not impair the usefulness of the cash-flow concept in investment decisions, but adds to its usefulness in stock valuation. The associated theory of stock valuation is based on the assumption that the cash receipts and the cash payments of the firm have been projected for each time period for ever. The Second Component:The second component of the equation in order to be explained let us take an example of PVGO and link it to the cash flow concept of stock valuation. Let us turn to a well-known company, Fledging Electronics, Where its r, is 15 percent, the company is expected to pay a dividend of $5 in the first year, and thereafter the dividend is predicted to increase indefinitely by 10 percent a year. We can therefore, use the simplified constant-growth formula to work out Fledging’s price:

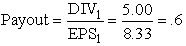

The important thing to note here is that:The first part of the equation is nothing than the discounted cash balance (V1) which will give its effect on the value of the stock.The second components (PVGO) is nothing then the pure profit defined as the return in excess of the normal discount rate on invested capital (-Io + Y1). So, under the Cash-Flow Theory of Stock Valuation, the price of the stock is determined by two components:The First Component:The first component is the present value of the future net cash-flows. Where management should project the future cash receipts and cash payments of the firm with various cash balances, subtract the payment from the receipts to determine net cash-flows, and then select that cash balance (i.e., purchase that amount of liquidity) which maximizes the present value of the net cash flows.In a world of certainty it would be unprofitable for a firm to hold cash. Any cash not needed immediately to make payments would be lent at interest, as liquidity is worthless if all future cash needs can be perfectly foreseen, and there are no flotation costs associated with lending, borrowing or repaying money. In the presence of uncertainty, cash balances are held because they provide liquidity. In principle, the decision to purchase liquidity by increasing cash balances or to sell liquidity by reducing cash balances should be analysed in the same way any other investment decision is analysed. An increase in cash balances is therefore considered as a purchase of liquidity and is defined as a cash payment. A reduction in cash balances is a sale of liquidity and is defined as a cash receipt. If a firm receives cash from the sale of a product and increases its bank balance, this involves both a cash receipt and a cash payment, so that the net cash flow is zero. Subsequently, when the firm reduces its bank balance to pay wages, this is again both a cash receipt and a cash payment, with a net cash-flow of zero The net cash-flow in any period therefore is the difference between cash received by the firm from purchasers, debtors, or banks, and the cash used by the firm to increase cash balances, to pay for goods and services, to pay interest or repay debt, or to lend and such flows must be associated with equity valuation.We could exclude all dealings in the firm’s financial obligations from the cash receipts and payments. The net-cash flow would then include transactions with debtholders as well as stockholders. The present value of the net cash flows would be the total value of all the firm’s financial obligations, and the value of the stock would be the total value of the obligations less the value of the debt. And this would provide the justification for the treatment of cash balances. cash balances are held because they provide liquidity. In principle, the decision to purchase liquidity by increasing cash balances or to sell liquidity by reducing cash balances should be analysed in the same way any other (investment) decision is analysed. HINT: Management should project the future cash receipts and cash payments of the firm with various cash balances, subtract the payments from the receipts to determine net cash-flows, and then select that cash balances (i.e., purchase that amount of liquidity) which maximizes the present value of the net cash flow. The net cash flow in any period therefore is the difference between cash received by the firm from purchasers, debtors, or banks, and the cash used by the firm to increase cash balances, to pay for goods and services, to pay interest or repay debt, or to lend. Such flows must be associated with equity obligations, i.e., the net cash flow is the cash flow between the firm and its stockholders. A positive net cash flow represents a cash payment by the firm to the stockholders, i.e., a dividend payment or a stock repurchase, while a negative net cash flow represents a cash payment by the stockholders to the firm, i.e., a new stock subscription.The associated theory of stock valuation is based on the assumption that the cash receipts and the cash payments of the firm have been projected for each time period for ever. We assume that there are no transaction or flotation costs, or any costs other than interest (or dividends) involved in borrowing or repaying money, or in buying or selling financial obligations. We also assume that stockholders are indifferent between capital gains and dividend income, so that we would ignore problems which arise because of the different taxes on income and capital gains. The net cash-flow would then include transactions with debtholders as well stockholders. The present value of the net cash flows would be the total value of all the firm’s financial obligations, and the value of the stock would be the total value of the obligations less the value of the debt. So, that the present value of the net cash flows is the value of the stock. Since the peculiar treatment of cash balances does not arise in evaluating any decision except the decision about the level of cash balances themselves, our treatment of cash balances does not impair the usefulness of the cash-flow concept in investment decisions, but adds to its usefulness in stock valuation. The associated theory of stock valuation is based on the assumption that the cash receipts and the cash payments of the firm have been projected for each time period for ever. The Second Component:The second component of the equation in order to be explained let us take an example of PVGO and link it to the cash flow concept of stock valuation. Let us turn to a well-known company, Fledging Electronics, Where its r, is 15 percent, the company is expected to pay a dividend of $5 in the first year, and thereafter the dividend is predicted to increase indefinitely by 10 percent a year. We can therefore, use the simplified constant-growth formula to work out Fledging’s price: Suppose that fledging has earnings per share of $8.33. Its payout ratio is then

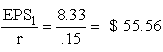

Suppose that fledging has earnings per share of $8.33. Its payout ratio is then In other words, the company is plowing back 1 - 0.6, or 40 percent of earnings. Suppose also that Fledging’ ratio of earnings to book equity is ROE = 0.25.This explains the growth rate of 10 percent:Growth rate = g = plowback ratio × ROE =.4 ×.25 =.10The capitalized value of Fledging’ earnings per share would be

In other words, the company is plowing back 1 - 0.6, or 40 percent of earnings. Suppose also that Fledging’ ratio of earnings to book equity is ROE = 0.25.This explains the growth rate of 10 percent:Growth rate = g = plowback ratio × ROE =.4 ×.25 =.10The capitalized value of Fledging’ earnings per share would be  But we know that the value of Fledging stock is $100. So, the question we can raise is, why investors are paying the difference of $44,44 per share. Let’s see if we can explain that figure:Each year Fledging plows back 40 percent of its earnings into new assets. In the first year Fledging invests $3,33 at a permanent 25 percent return on equity. Thus the cash generated by this investment is 0.25 x 3,33 = $.83 per year starting at t = 2. The net present value of the investment as of t = 1 is

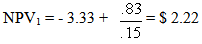

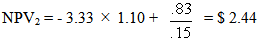

But we know that the value of Fledging stock is $100. So, the question we can raise is, why investors are paying the difference of $44,44 per share. Let’s see if we can explain that figure:Each year Fledging plows back 40 percent of its earnings into new assets. In the first year Fledging invests $3,33 at a permanent 25 percent return on equity. Thus the cash generated by this investment is 0.25 x 3,33 = $.83 per year starting at t = 2. The net present value of the investment as of t = 1 is  Everything is the same in year 2 except that Fledging will invest $3,67, 10 percent more than in year 1 (remember g =.10). Therefore at t = 2 an investment is made

Everything is the same in year 2 except that Fledging will invest $3,67, 10 percent more than in year 1 (remember g =.10). Therefore at t = 2 an investment is made  These are the forecasted future cash-flow growing at 10 percent per year, to calculate their present value we use the simplified DCF formula,Present value of growth opportunities = PVGO

These are the forecasted future cash-flow growing at 10 percent per year, to calculate their present value we use the simplified DCF formula,Present value of growth opportunities = PVGO  Now everything checks:Share price = present value of level stream of earnings + present value of growth opportunities =

Now everything checks:Share price = present value of level stream of earnings + present value of growth opportunities =  + PVGOThen, Po = $55.56 + $44.44 = $100Why is Fledging Electronics a growth stock? Not because it is expanding at 10 percent per year. It is a growth stock because the net present value of its future investments accounts for a significant fraction (about 44 percent) of the stock’s price.Here we have used the NPV to calculate this fraction of the stock’s price linked to the future cash-flow generated by the future investments of the firm. Stock prices today reflect investors’ expectations of future operating and investment performance. Growth stocks sell at high price-earnings ratios because investors are willing to pay now for expected superior returns on investments that have not yet been made. Michael Eisner, the chairman of Walt Disney Productions, made the point this way: “In school you had to take the test and then be graded. Now we’re getting graded, and we haven’t taken the test. “This was in late 1985, when Disney stock was selling at nearly 20 times earnings. See Kathleen K. Weigner. “The Tinker Bell Principle,” Forbes, December 2, 1985, p. 102.So, our second components - PVGO - is nothing then the pure profit or the concept of profit defined as the return in excess of the normal (discount rate) on invested capital. Cash-flow theory says that all pure profit is earned when the stock value makes a change that had not been anticipated by the market. The market value of the stock is always determined in such a way that the expected return, net cash-flow (dividends) plus capital gains, is the normal return on the market value at the start of the period. If all goes as expected, the actual return, business profit, will be the expected normal return, and pure profit will be zero. If expectation changes, a pure profit or loss is made immediately as the stock price makes an unexpected adjustment so that the newly expected future returns will equal a normal return on the new stock value (investment).

+ PVGOThen, Po = $55.56 + $44.44 = $100Why is Fledging Electronics a growth stock? Not because it is expanding at 10 percent per year. It is a growth stock because the net present value of its future investments accounts for a significant fraction (about 44 percent) of the stock’s price.Here we have used the NPV to calculate this fraction of the stock’s price linked to the future cash-flow generated by the future investments of the firm. Stock prices today reflect investors’ expectations of future operating and investment performance. Growth stocks sell at high price-earnings ratios because investors are willing to pay now for expected superior returns on investments that have not yet been made. Michael Eisner, the chairman of Walt Disney Productions, made the point this way: “In school you had to take the test and then be graded. Now we’re getting graded, and we haven’t taken the test. “This was in late 1985, when Disney stock was selling at nearly 20 times earnings. See Kathleen K. Weigner. “The Tinker Bell Principle,” Forbes, December 2, 1985, p. 102.So, our second components - PVGO - is nothing then the pure profit or the concept of profit defined as the return in excess of the normal (discount rate) on invested capital. Cash-flow theory says that all pure profit is earned when the stock value makes a change that had not been anticipated by the market. The market value of the stock is always determined in such a way that the expected return, net cash-flow (dividends) plus capital gains, is the normal return on the market value at the start of the period. If all goes as expected, the actual return, business profit, will be the expected normal return, and pure profit will be zero. If expectation changes, a pure profit or loss is made immediately as the stock price makes an unexpected adjustment so that the newly expected future returns will equal a normal return on the new stock value (investment).4. The Cash-Flow Concept of Dividend Policy

- Although the problem of dividends were approached in a variety of ways, our preference said James E. Walter in his article on “Dividend policy and its influence on the value of the enterprise ” is to commence with net cash flows from operations and to consider the effect of additions to, and subtractions from, these flows upon stock values. Not only does this starting point by pass certain measurement problems, but it also directs attention to the relevant variables in a manner that other approaches may not. The question is whether dividends are in some sense of the word weighted differently from retained earnings at the margin in the minds of marginal investors.Net cash-flows from operations are available for (1) the payment of interest and principal on debt or the equivalent and (2) capital expenditures and dividend payments. Operating cash flows can be supplemented in any period by debt or equity financing. Debt financing creates obligations to pay out cash in future periods and thereby reduces cash flows available for capital expenditures and dividend in those periods. Equity financing in turn, diminishes the pro rata share of total cash-flows available for dividends and reinvestment.Before the thrust shifted to dividends, the basic issue in the cost of capital discussion was one of dividing the stream of operating cash-flows between debt and equity in such a manner as to maximize the market value of the enterprise. In an analogy to cost of capital, and when dividends enter the picture, the issue becomes one of dividing the stream of operating cash-flows among debt, dividends and reinvestment in such a way as to achieve the same result. The principal difference in the character of the analysis is that it may no longer be feasible to assume that the size and shape of the stream of operating cash-flows is independent of the manner in which it is subdivided.Much the same as contractual interest payments and other financial outlays, the continuation of cash dividends at their prevailing rate is assigned a priority by management. In such instances, the burden of oscillations in operating cash-flows is placed upon lower-priority outlays, namely capital and related expenditures, unless management is both willing and able to compensate by adjusting the level of external financing. Even if management is willing to seek funds outside the firm, the uncertainties inherent in the terms under which external financing can be obtained in the future reduce the likelihood of such action in the event of operating cash deficiencies in any period. The reason is that current cash dividends may well be capitalized somewhat differently from anticipated future cash-flows.It may be observed that the relative instability of expenditures designed to augment future cash-flows shows up even in the aggregate. The change from year to year for new plant and equipment averaged 19 percent for all manufacturing corporations in the post period to 1961, as compared with 9 percent for cash dividends. The maximum declines from one year to the next were 40 percent for new plant and equipment and but 2 percent for dividends.Again, as in the case of debt versus equity, investor reactions to dividend policy changes can nullify in whole or in part their price effect. Whenever the stockholder is dissatisfied with the dividend payout, the balance between present and future income can be redressed by buying or selling shares of stock and perhaps by other means as well. for instance, by “lending” or “borrowing” on the same risk terms that cash dividends are paid. If dividends are deemed insufficient, the desired proportion of current income can be obtained by periodically selling part of the shares owned. If current income is too high, cash dividends can be used to acquire additional shares of stock. The one thing that shareholders cannot do through their purchase and sale transactions is to negate the consequences of investment decisions by management. If, as may well be the case, investment decisions tend to be linked with dividend policy, their neglect in the analysis of dividend effects seems inappropriate.The conditions for no dividend effect under which changes in dividend payout have minimal influence upon stock values can now be stated. For the most part, they follow from the logics of stream-splitting:The level of future cash-flows from operations, that is the growth rate, is independent of the dividend-payout policy. In essence, this condition implies that the impact of a change in dividend payout upon operating cash-flows will be exactly offset (or negated) by a corresponding and opposite change in supplemental (or external) financing. An increase in dividends can be offset only by the sale of equity shares. So, an increase in dividend payout will leave operating cash-flows unchanged in the aggregate, but the share of future cash-flows accruing to existing stockholders will decline, since additional stock has to be sold to finance the planned capital outlays. The existing shareholder can, of course, reconstitute his former pro rata position by purchasing shares in the market with his incremental dividends.Implicit in these remarks is the presumption that the market completely capitalizes anticipated growth in operating cash-flows. New shares are thus acquired at a price that returns new investors only the going market rate for the relevant class risks. The present value of extraordinary returns from investment by the corporation goes to existing stockholders, rather than to new shareholders. To the degree that the anticipated level of operating cash-flows, that is, the growth rate, is connected with the dividend payout for one reason or another, the market value of the firm may be conditioned by variations in dividend payout. The policy changes may be unexpected, and their price effect lies at least upon the relation between the internal and market rates of return. If the former exceeds the latter, the present value of a dollar employed by the firm (other things being equal) will be greater than a dollar of dividends distributed and invested elsewhere. This issue was considered in 1956 paper by James E. Walter. From here rises a Cash-Flow Concept of Stock Valuation where the value of the stock is the present value of the future net cash-flows. And this Net Cash-Flow is the cash-flow between the firm and its stockholders; a positive net cash-flow represents a cash payment by the firm to the stockholders, while a negative net cash-flow represents a cash payment by the stockholders to the firm. The question that arises here is, do the weights employed or in other words, the discount factors, independent of the dividend-payout policy? Provided that the system of weights remains unchanged, a change in current cash dividends will alter the stockholder’s stake in future cash-flows.According to the question of the independence of the weights used from the dividend-payout policy, a change in dividend payout undoubtedly disturbs the investors in that stock to some extent unless the modification was anticipated previously. Insofar as costs of one kind or another and other factors prevent the shareholders thus activated from completely reconstituting their old position and thereby give rise to a new and different equilibrium point. The fact that the substitutions of future cash-flows for present dividends superimposes an element of market risk upon the basic uncertainty of the operating cash-flow stream. As contrasted with cash dividends in which the stockholder receives a dollar for each dollar declared, there is no telling what price the shareholder will realize in the market at any given time for his stake in future cash-flows. From here rises the need for a theory of stock pricing based on cash-flow analysis.A recent article by John Lintner, concludes that “generalized uncertainty “ is itself sufficient to insure that shareholders will not be indifferent to whether cash dividends are increased or reduced by substituting new equity issues for retained earnings to finance given capital budgets.The frequently observed association between dividend-payout policy, capital structure, and rate of growth is a useful case in point. The survival of the corporation ordinarily does not depend; in the short run at least, upon any specific rate of growth. The prime considerations affecting growth, apart from profit opportunities, are (1) the willingness of corporations to go into the public market place for additional funds and (2) their attitude toward dividends, including their willingness to return unneeded funds to the investors.For firms that are reluctant to get involved in external financing, and there appear to be many, then the burden of expansion rests upon residual internal sources, that is, operating cash-flows less cash dividends and debt servicing net of additions to debt. Decisions to increase or decrease dividends thus condition the value of the enterprise as long as the returns on new investments differ from the market rate. Whenever the available investment opportunities are unable to earn their keep, the specter of liquidating, dividends or repurchase of shares or debt retirement arises. If there is no debt outstanding and if the repurchase of shares is not contemplated, the burden of liquidation falls upon dividend payout.So, we can conclude that we should have a look not on the dividend effect on the value of the enterprise but on the effect of cash-flow from operation on stock valuation, because and if the change in the level ( increase or decrease ) of dividend would affect the future cash-flow from operation not necessary on the aggregate, but on the share of future cash-flows accruing to existing stockholders. This must have its effect on the value of the stock and indirectly we should discount the (decrease - increase) in the cash-flow from operation and compare it to the discounted (decrease or increase) in cash dividend, and find out the net effect on the price of the stock. This would bring us back to our definition of the cash-flow concept of stock valuation where the net cash-flow when discounted will have its effect positively or negatively on the value of the enterprise and this Net Cash-flow is nothing than the flow of cash between the firm and its stockholders.

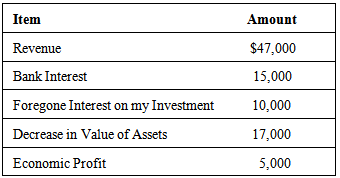

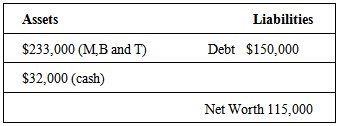

5. The Cash-flow Concept of Stock Valuation and the Cost of Capital

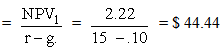

- To solve the problem of the calculation of the cost of capital or the cost of equity or the required rate of return by the shareholders or the implicit cost. Let us have a look on the benefit of the net cash-flow.We would show in this part that depreciation and implicit cost need not be considered since they don’t give rise to cash-flows. Cash-flow analysis accounts for these costs much more simply, by charging the cost as a cash payment when the asset is bought.Calculating Project NPV:Maple Media is considering a proposal to enter a new line of business. In reviewing the proposal, the company’s CFO is considering the following facts:The new business will require the company to purchase additional fixed assets that will cost $600,000 at t = 0. For tax and accounting purposes, these costs will be depreciated on a straight-line basis over three years. (Annual depreciation will be $200,000 per year at t = 1, 2, and 3.)At the end of three years, the company will get out of the business and will sell the fixed assets at a salvage value of $100,000.The project will require a $50,000 increase in net operating working capital at t = 0, which will be recovered at t = 3.The company’s marginal tax rate is 35 percent.The new business is expected to generate $2 million in sales each year (at t = 1, 2, and 3). The operating costs excluding depreciation are expected to be $1.4 million per year.The project’s cost of capital is 12 percent.What is the project’s net present value (NPV)? Solution:

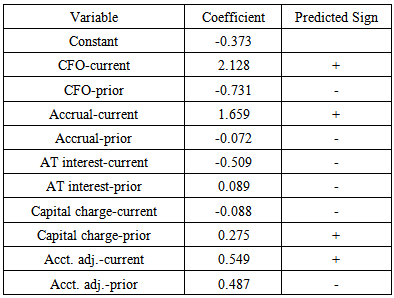

Let us now calculate the Economic profit. Then calculate the discounted present value of the economic profit: Economic profit = Earnings – Cost of equityHint: Equity is decreased every year by the depreciation Year 1 = $260 000 – ($650 000 x 12%) = $182 000Year 2 = $260 000 – ($450 000 x 12%) = $206 000Year 3 = $260 000 – ($250 000 x 12%) = $230 000PV of Economic profit = $182 000/ 1.12 + $206 000 / (1.12)2 + $230 000 / (1.12)3 = $490 431.39 ≈ $490 431We conclude that the discounted economic profit is equal to the discounted cash-flow or the Net Present Value (NPV). The important thing to notice is that Depreciation and implicit interest need not be considered since they do not give rise to cash flows. Cash-flow analysis accounts for these costs much more simply by charging the cost as a cash payment when the asset is bought.This come to emphasize what have been already challenged by Professors Biddle, Bowen, and Wallace in their article “EVA and its Critics” in the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Summer 1999.Where they argue that Cash-flow from operations, accruals and interest expense, are already included in the profits numbers that companies are required to disclose in their annual reports. The question is whether or not the two elements not explicitly included in mandated disclosures, the capital charges and accounting adjustments are significantly related to stock prices. Unhappily the answer is NO. They show that while the cash-flow and actual components are consistently significant, the components unique to EVA are not.In our example we excluded the salvage value. What about if we add the salvage value to our calculation: NPV = -$650,000 + $460,000/1.12 + $460,000/(1.12)2 + $575,000/(1.12)3= -$650,000+$410,714.29+$366,709.18 + $409,273.64= $536,697.11 ≈ $536,697.Under the discounted economic profit we consider the salvage value as a cash payment from the firm to the shareholders and in our case it is equal to:Equipment sale $ 100 000Taxes on sale $ (35 000)PV (Economic profit) = $182000/1.12+ $206 000 /(1.12)2 + $230 000 /(1.12)3 + $ 65 000 /(1.12)3 = $536 697.1119 ≈ $536 697The important thing to notice is that Depreciation and implicit interest need not be considered since they do not give rise to cash flows. Cash-flow analysis accounts for these costs much more simply, by charging the cost as a cash payment when the asset is bought.

Let us now calculate the Economic profit. Then calculate the discounted present value of the economic profit: Economic profit = Earnings – Cost of equityHint: Equity is decreased every year by the depreciation Year 1 = $260 000 – ($650 000 x 12%) = $182 000Year 2 = $260 000 – ($450 000 x 12%) = $206 000Year 3 = $260 000 – ($250 000 x 12%) = $230 000PV of Economic profit = $182 000/ 1.12 + $206 000 / (1.12)2 + $230 000 / (1.12)3 = $490 431.39 ≈ $490 431We conclude that the discounted economic profit is equal to the discounted cash-flow or the Net Present Value (NPV). The important thing to notice is that Depreciation and implicit interest need not be considered since they do not give rise to cash flows. Cash-flow analysis accounts for these costs much more simply by charging the cost as a cash payment when the asset is bought.This come to emphasize what have been already challenged by Professors Biddle, Bowen, and Wallace in their article “EVA and its Critics” in the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Summer 1999.Where they argue that Cash-flow from operations, accruals and interest expense, are already included in the profits numbers that companies are required to disclose in their annual reports. The question is whether or not the two elements not explicitly included in mandated disclosures, the capital charges and accounting adjustments are significantly related to stock prices. Unhappily the answer is NO. They show that while the cash-flow and actual components are consistently significant, the components unique to EVA are not.In our example we excluded the salvage value. What about if we add the salvage value to our calculation: NPV = -$650,000 + $460,000/1.12 + $460,000/(1.12)2 + $575,000/(1.12)3= -$650,000+$410,714.29+$366,709.18 + $409,273.64= $536,697.11 ≈ $536,697.Under the discounted economic profit we consider the salvage value as a cash payment from the firm to the shareholders and in our case it is equal to:Equipment sale $ 100 000Taxes on sale $ (35 000)PV (Economic profit) = $182000/1.12+ $206 000 /(1.12)2 + $230 000 /(1.12)3 + $ 65 000 /(1.12)3 = $536 697.1119 ≈ $536 697The important thing to notice is that Depreciation and implicit interest need not be considered since they do not give rise to cash flows. Cash-flow analysis accounts for these costs much more simply, by charging the cost as a cash payment when the asset is bought.5.1. Debt or Equity Financing under the Cash-flow Theory of Stock Valuation

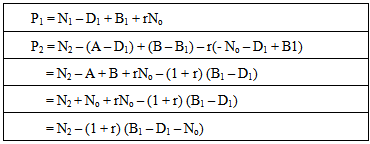

- If we continue with the same example of Maple Media Corporation using debt financing, we will find out that the discounted present value of the economic profit using debt financing is always equal to the Net Present Value meaning that the way of financing is not affecting the value of the firm as long as the net cash-flow is not changing. We will have access to reducing debt financing only when the net cash-flow is decreasing in order to reduce the effect of reduction on the net cash-flow on the value of the firm. Though capital structure decisions are influenced by a firm’s ability to generate future cash flows, the theoretical literature has neglected the dynamic relation between leverage and firm specific earnings behaviour. HOWEVER, with the cash-flow theory of stock valuation, under a theory of continuous time, we have adjustments in the business, capital structure, policy and optimality on hour per hour and day per day basis in order to avoid the risk inherent in the capital structure of the business. We will use the article of Steven Raymar “A Model of Capital Structure when Earnings are Mean-Reverting” to give a clear meaning to a theory of continuous time. Raymar assumes a linkage between firm value and earnings, which would affect the optimal leverage decisions. So, leverage is reviewed and reoptimized every period and the variability of leverage is positively related to variability in earnings and firm value. EBIT follows an exogenous process that is unaffected by leverage or default. Its parameters are such that the firm never liquidates if optimal policies are followed. The autocorrelation between earnings at time t and t+1 is , if =0, earnings are serially independent, and as approaches 1 the process tends toward a random walk, implication of the process is that, while a firm may experience a bad or a good year, over time it is expected to revert to a normal performance level. An unlevered firm is valued as the discounted sum of expected future after-tax earnings, because stockholders receive the firm’s income stream in perpetuity, it must never be optimal for them to relinquish ownership, as it might be if income were negative, this would be optimal for stockholders to maintain the unlevered firm as a going concern, given any feasible earnings realization. When debt is introduced in the financing activities of the corporation, the firm is assumed to issue single period debt and to optimally recapitalize at each date. As firm optimally and continuously recapitalize, under continuous time the focus is not on conflicts of interest among claimants, because debt has a one period maturity, the optimal policy should maximize both equity and firm value, so adjustments are made on daily basis and when earnings are low, a firm should optimally reduce its leverage ratio and debt level or otherwise said reducing its cost of capital and the earnings process permits one firm to be safer than another over a short horizon. At each date, the firm is recapitalized so as to maximize the wealth of current owners. This process is costless if the firm is solvent, but otherwise the transfer of ownership and control is assumed to induce bankruptcy reorganization costs and the model is unaffected as long as a clear distinction between debt and equity remains. Default that caused liquidation in the past is now resulting in an optimal reorganization. Since an optimal debt decision needs to consider only the future cash-flows of the firm and is independent of past earnings and debt levels. Then a change in the autocorrelation between earnings at time t and t+1, also affects future debt decisions and firm values. From here rises a cash-flow concept of profit associated with the cash-flow theory of stock value.

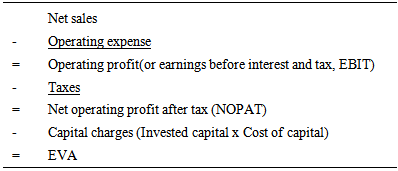

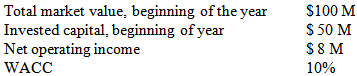

6. The Traditional Performance Measures

- The problems and the effective performance measures like Return on Asset (ROA), Return on Equity (ROE), Return on Investment (ROI) and Economic Value Added (EVA), and how these measures correlate positively with stock-returns and stock prices, will be discussed below.

6.1. Problems with Return on Equity (ROE)