-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2014; 3(3): 174-184

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20140303.04

Foreign Capital Inflows and Entrepreneurship in Nigeria: The Implication for Economic Growth and Development

John O. Udoidem1, Paul Udofot2

1Department of Banking and Finance, University of Uyo

2Department of Business Management, University of Uyo

Correspondence to: John O. Udoidem, Department of Banking and Finance, University of Uyo.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Entrepreneurship is a pre-requisite to economic growth and development. Entrepreneurs are driving forces and major contributors to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). To enhance the activities of the entrepreneurs, classical economists are of the opinion that capital inflows should be encouraged to boast their efforts. However, the alternative viewers have argued against the idea. This work focuses on capital inflows into Nigeria, entrepreneurship, economic growth and development. The study is descriptive and correlation in nature. Qualitative and quantitative approaches are adopted. Data from Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) Statistical Bulletin and National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) are used for analysis. Findings have shown that capital inflows enhance activities of entrepreneurs thereby impacting positively on economic growth and development. The prime recommendation in the study is that more effort should be geared towards attracting more inflows.

Keywords: Oreign Capital, Inflows and Entrepreneurial Development

Cite this paper: John O. Udoidem, Paul Udofot, Foreign Capital Inflows and Entrepreneurship in Nigeria: The Implication for Economic Growth and Development, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 3 No. 3, 2014, pp. 174-184. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20140303.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The classical economists postulated that the flow of capital into low income countries helps in providing resources to close savings – investment gap in the recipient countries. Their claim is that capital inflows are desirable in developing economies because they augment domestic resources and enhance activities of entrepreneurs. Many developing countries believe in this idea and encourage an inflow of foreign capital (Yang-Yung, 1997). Nigeria, like other developing countries, has adopted policies over the years to encourage foreign capital inflow. The effort started in the mid 1950s and has continued up to the time of this study. This offshore capital inflow in Nigeria was last reported at N7.7 billion (only foreign direct investment and portfolio investment in 2010) (World Bank Report – 2011). According to Ernest and Young, Nigeria has constantly ranked among the largest recipient of foreign capital in Africa, particularly, foreign direct investment. Over the last decade, the country, made about $120 billion as proceed of foreign investments (www.ey.com/gl/en/services/strategic- growth-market/centre-for-entrepreneurship-and-innovation).Both private and public sectors of Nigerian economy have utilized the foreign capital to boast their entrepreneurial capabilities in line with government development plans. Over time, government’s plan to stimulate inflow of resources was with expectation to speed up growth and transform the economy in line with classical economist’s prescription. In particular, rapid increase in Gross Domestic Product (G.D.P) and GDP per capita were expected. Other expectations included improved balance of payment, creation of employment opportunities and stimulation of the overall development of the economy. The economic situation of the early 1980s sparked off the debate on the desirability of foreign capital inflow into the country. While some scholars expressed positive views, others doubted the achievements. Critics evidenced the lack of corresponding growth in entrepreneurial activities to support their opinion. Successive governments have however continued to rely on stimulation of foreign capital inflow as a strategy for growth in activities of the entrepreneurs. The above has rekindled the interest for further investigation. The main objective therefore is to assess the contribution of foreign capital to growth in output of entrepreneurs in Nigeria. To achieve this objective, we attempted to: examine the structure of capital inflow into Nigeria; examine the distribution of the inflow; evaluate the contribution of foreign capital to growth performance. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Nigeria is used as measurement of output of entrepreneurs in Nigeria. Hypothesis tested in the study is stated thus:Ho: Capital inflow into Nigeria has no significant effect on economic growth.

2. Review of Related Literature

2.1. The Role of Foreign Capital in Less Developed Countries (LDCs)

- It is believed by neoclassical economists that international capital flows increase the volume of international investment. Capital inflow, it is argued, finances projects and production activities, and has the capacity to generate a good number of new employment opportunities (Williamson, 1995). Foreign capital inflow is widely considered a very welcome idea for raising level of investment and for encouraging economic growth as well as for building-up of foreign exchange reserve (Yang-Yung, 1997). Supporting this view, Pontes (1999) believes capital inflow is widely embraced by developing economies to raise their level of investment as well as build up their foreign exchange reserves. According to Williamson (1995), “…inflow is seen as a piece of good fortune that permits a country to enjoy a larger real income”.Empirical surveys have established positive impact of capital inflow on economic growth and development of host countries (Blomstrom and Kokko, 2003); (Caves, 1974); (Markusen, 1995) and (Chowdury & Mavrotas, 2003). Calvo, G., Leiderman, L. and Reinhart, C. (1996) writing in support of the positive role of capital inflow stated as follow:After about a decade in which little capital flowed to the developing nations, capital has started in the 1990s to move from industrial countries like USA, and Japan to developing regions like Latin America, the Middle East and parts of Asia as well as Africa. The preliminary data have indicated that in most countries, resurgence in economic growth accompanied the increase in capital inflow. P. 123.Also, Larosiene (2004) argued that “… countries are involved in international transactions and are, in particular, very dependent on private inflows, and advised nations to count on flows to do the bulk of financing. Still in support of the importance of capital inflow; world economic leaders during the G-20 London Summit of April 12, 2009, emphasized that international capital flows should be encouraged to improve the world economy, particularly, the economies of the host countries (G-20 Communiqué – www.fco.gov.uk). The economic theories of capital inflow, the product life cycle theory, and the motivational theory and others are in agreement that capital inflows impact positively on economic growth of the host or recipient country (Mkpakan, 2004). The above views have not received the support of many authors. In the mid 1990s some economists argued that foreign capitals have no positive effect on economic growth of LDCs. The alternative view argues that removing one obstacle-restriction on capital movement, while there is the presence of other distortions that often exist in emerging markets may not necessarily enhance welfare. (Younger, 1992; White & Wignaraja, 1992). This alternative view gained particular relevance after the onset of the Asian Crisis. This crisis focused attention on how malfunctioning domestic financial markets in recipient countries and poor risk management in capital exporting countries could undermine the gains on the macroeconomic and growth effects of capital liberalization. A large empirical literature has emerged during the past decade in an attempt to settle the issue. In Tong & Wei (2009), Cross-country empirical literature on the relationship between capital inflow and economic growth has been extensively surveyed by these alternative viewers – Eichengreen (2003); Prasad, Rogoff, Wei and Kose (2003) and (2009), Henry (2003). Most of their findings revealed that capital inflow impacts negatively on economic growth of the LDCs. This formed the basis of their argument. The critics of capital account liberalization interpreted the findings to mean that liberalization does not promote growth in LDCs.

2.2. Foreign Capital Inflow and Entrepreneurship

- Entrepreneurship is the ability to get things done. That ability involves creativity, vision, willingness to accept risk and a talent for translating vision into reality. Entrepreneurs create small, medium and large firms; produce new products; and transform the landscape of the economy. Entrepreneurship is an indispensable ingredient in economic growth and development. The traditional theory of a firm explains the existence of foreign entrepreneurs through foreign direct investment. It affirms that foreign firms would use the factors of production for expansion and for growth in the host’s country. The goods that would be produced would be distributed through out the economy and sold at marginal cost to enhance economic welfare for all (Hawkin, 1973).Therefore, foreign direct investment is transfer of entrepreneurship, management skill, physical capital and human capital. It involves transfer of sophisticated skills in production technology, technical knowledge, general know-how, and managerial capacities. It also involves transfer of creativity, vision, willingness to accept risk and a talent for translating vision into reality. For instance, some industrial investments in Nigeria are successful because of investment of foreign entrepreneurial expertise. Apart from foreign direct investments, the international portfolio investment or portfolio equity impacts on entrepreneurial development in the recipient country. This refer to the flow across national boundaries of funds for financing investments in which the lender does not gain operating control over the borrower (Udoidem, 2012). When individuals, firms, or government buy the bonds of a foreign firm or government, there is international transaction of transfer of funds. This type of transaction involves low transaction and transportation costs. All that is involved in most cases is an electronic transfer of funds accomplished almost instantaneously at very little cost using modern computer technology. This practice is common in financial markets such as the stock exchange.Transfer of fund through portfolio investment or equity augments domestic savings thereby closing or narrowing the savings-investment gap of the recipient country. This process attempts to increase the entrepreneurial capabilities in the recipient country thereby expanding her production possibility frontier. For instance, if Nigerian firm issues bonds and sell some of these bonds to a resident in Germany (who thereby makes loan to Nigerian firm), the Nigerian firm typically uses the borrowed funds to buy a piece of physical capital thereby increasing her capital stock. Increase in capital stock of the Nigerian firm enables entrepreneurial development in the company as this could lead to entrepreneurial ability to translate vision into reality, produce new products and transform the landscape of the economy. Another way foreign capital could impact on entrepreneurial development is through debt. International Monetary Fund (IMF) lends money to member countries with much sympathy to the developing countries. The public sectors of the recipient countries are assisted to enhance efforts of entrepreneurs through financing of projects toward economic growth and development. IMF expanded its membership to generate a large group of potential borrowers that had low per capita income. This led to a rise in Africa membership for opportunity to borrow from the IMF. The introduction of Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) in 1999 enabled the IMF to continue offering longer-term concessional loans to low income countries especially sub Saharan Africa (Boughton, 2004).Another type of debt involved is commercial lending, is lending made by foreign lenders. The source of such lending may be foreign banks or clubs such as the Paris Club and London Club. Low income countries rely much on commercial borrowing to aid infrastructural development in order to enhance entrepreneurial activities. Government, firms and individuals are involved in attracting foreign inflow via commercial lending and these funds are meant for investment in the local economy for economic growth and development. Finally, the other type of inflow is the official flow. This refers to aids, grants and other voluntary flows of capital usually from the rich countries to poor ones (Anyemedu, 2002). The purpose of official flow like others is still to assist the low income countries to enhance entrepreneurial activities aimed at achieving economic growth and development.

2.3. Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth

- A global consensus emerged among world leaders that entrepreneurship is a key strategy for economic growth and development. They encouraged high profile programme to encourage entrepreneurship in almost every major city, region and country as there exist a painful gap between public leaders’ new commitment to entrepreneurship and their regions abilities to internationally create programmes and processes that will systematically and meaningfully stimulate entrepreneurial growth (Naude, 2013). This study in line with the global consensus opines that foreign capital inflow could encourage entrepreneurship thereby impacting positively on economic growth.Daniel Isemberg (2010) in his work “How to start Entrepreneurial Revolution” in line with the idea of the world leaders postulated that entrepreneurs are most successful when they have access to the human, financial and professional resources they need, and operate in an environment to which government policies encourage and safeguard entrepreneurs. His idea also suggests that where there is a savings-investment gap in a local economy, effort should be made internationally to breach the gap. He referred to this network as “the entrepreneurship ecosystem”.Chell and Ozkan (2010) sees entrepreneur as someone who is willing to bear risk of a business venture, innovative and one who brings about increase in output in the society. Andre Van Stel, Martin Carree and A. Roy Thurik in their work “The Effect of Entrepreneurial Activity on National Economic Growth” explains that entrepreneurial activity is assumed to be important aspect of the organization of industries most conducive to innovation activity and unrestrained competition. Their findings revealed that entrepreneurial activity by nascent entrepreneurs and owners/managers of young business affects economic growth, but that these effects depend upon the level of per capita income. It plays different role in countries in different stages.Still more, Carree and Thurik in their study emphasized on the consequences of entrepreneurship for macroeconomic growth. They identified types and their relation to economic growth, the effect of the choice between entrepreneurship and employment. They also explain entrepreneurship in endogenous growth model. Their empirical evidence show that entrepreneurship impacts positively on macroeconomic growth. Their idea was in line with the work conducted by Tesreau and Gialazauskas. They see the importance of entrepreneurs and claim that entrepreneurs play a vital role in economic growth. That they help to build communities in ways such as providing jobs, conducting business locally, creating and participating in entrepreneurial networks, investing in economic and social impact of entrepreneurship.Other works in support of the role of entrepreneurship in economic growth include: Daniel (2010) in his work “The Role of Entrepreneurship in Economic Growth”, and Stel, (2006) in his book, “Empirical Analysis of Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth – International Studies in Entrepreneurship”.

2.4. Review of Empirical Literature about Foreign Capital and Economic Growth in Nigeria

- Dauda (2008) investigated the trends, behavioural patterns and growth implications of foreign private capital flows in Nigeria. It is a contribution to the often-debated role of foreign capital flows into economies of developing countries. It examined the magnitude and impact of foreign private capital flows on economic performance in Nigeria. He used secondary data on some relevant financial and macroeconomic indicators from 1986 – 2006. Descriptive statistics, Pairwise Granger – causality test and Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regressions were used to analyze the interaction between indices like the degree of openness, domestic investment. However, there is positive relationship between index of openness, foreign private capital flow; proxied by FDI and equity or portfolio investment and GDP during the period under review. The major policy recommendation that emerges from this study is the need to put in place the policies that would promote stable and conducive macroeconomic environment, which would encourage foreign capital inflows into the economy of Nigeria. In addition to the work by Dauda; Ayanwale and Bamire (2004) have worked on Direct Foreign Investment and Firm Level Productivity. They acknowledged the benefits of DFI which seems to be more than the demerits as such explains the move by developing countries, seeking to attract foreign direct investment. The study examined the impact of foreign direct investment on the productivity at the firm level in the agro-allied sector of the Nigerian economy. Data were obtained from agro-allied companies listed in the first tier market and the second tier foreign exchange markets as contained in the publication of the Nigeria Stock Exchange and Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, correlation and regression techniques. A comparison of the firm level productivity measures shows that foreign firms productivity is higher than that of their domestic counterpart. The result of the impact of foreign direct investment on productivity growth showed that there is positive and significant spillover effect at the firm level. However, the extent of the spillover may not extend to the sectoral level nor the entire economy. Another empirical study in Nigeria is that of Okomoh (2004), on the Role of Business in Society, Foreign Direct Investments and their impact on sustainable Development in Nigeria. According to Okomoh, Nigeria, being a developing economy has not been different from other developing economies in using FDI as a strategy for achieving economic growth and development. However, unlike a country like Malaysia, Nigeria, in spite of its huge deposit of human, natural and material resources has failed to achieve rapid economic growth due to several factors, the principal of which is an unstable political environment. In his study, he used mainly descriptive statistics for the analysis. He found out that capital inflow is capable of making significant and direct contribution to sustainable development in Nigeria. However, it might, in the long run, not guarantee sustainable development in its entire ramification. He attributes this to the political instability of the country.

3. Methodology

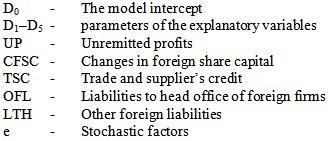

- This study is descriptive and correlation in nature. Data on inflows of foreign capital and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) are collected for analysis. The data were obtained from Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) Statistical Bulletin and documented data by National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) as well as internet network system. Correlation coefficient ‘r’ is used to determine the nature and degree of correlation between the dependent and independent variables, while the square of the correlation ‘r2’ is used for judging the explanatory power of the independent variables. It is the measure of the extent to which the explanatory variable(s) is responsible for the changes in the dependent variable (Koutsoyannis, 1983). Regression Model The effect of capital inflows into Nigeria on economic growth. Model showing the effect is expressed as; GDPg = F(UP, CFSC, TSC, LHO, OFL). Where GDP is used as proxy for economic growth. The functional relationship is specified thus:GDPg = Do + D1 (UP)E + D2 (CFSC)t + D3 (TSC)t + D4 (OFL)t + D5 (LTH)t + e Where: Do = The Model Intercept D1 - D5 Parameters of the explanatory variables (the variables used are identified in 4.1.4)A Prior expectation It is expected that increase in components of capital inflows to Nigeria lead to increase in GDP. Test of Hypothesis F – test is used to test the statistical significance or reliability of the parameter estimates of the model. The decision rule is that using 5% significance at n – k (n = number of observations and k = number of parameters estimated) degrees of freedom, we reject the null hypothesis, accepting the alternative if the computed value of F is greater than the theoretical value of F.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Structure of Capital Inflows

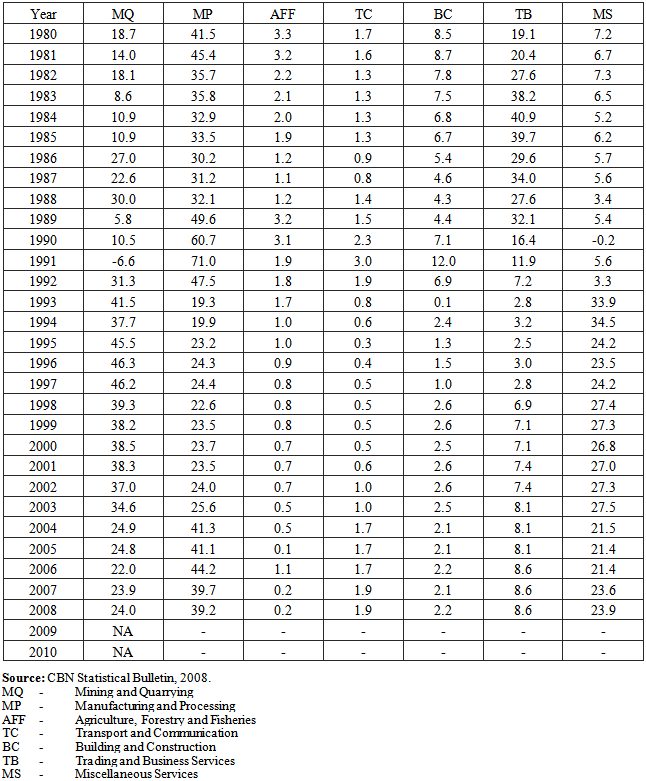

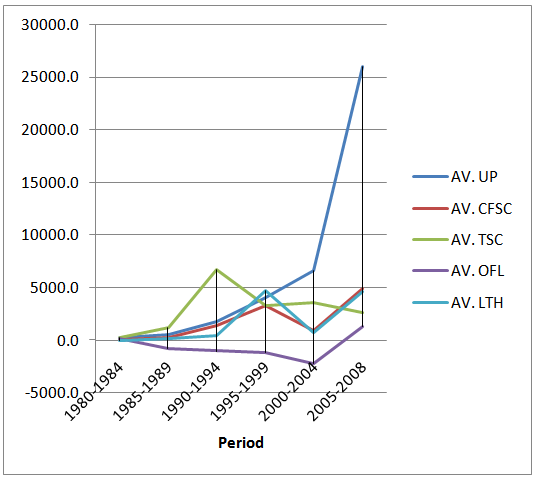

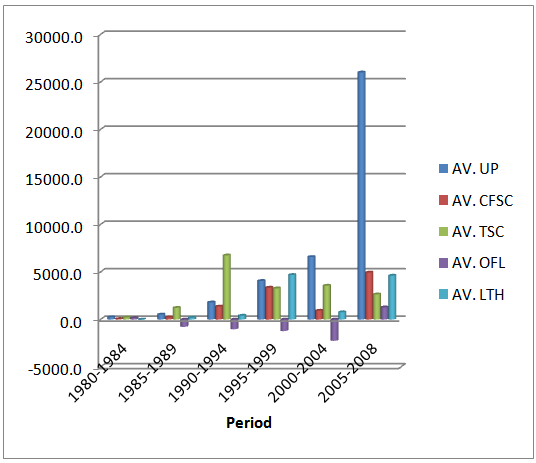

- Capital inflows into Nigeria, as outlined by Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), are Unremitted Profits (UP); Changes in Foreign Share Capital (CFSC); Trade and Suppliers’ Credit (TSC); Liabilities to Head Office (LHO) and Other Foreign Liabilities (OFL) such as external borrowing. The trend of these components is presented in table 4.1 from 1980 – 2010.From 1980 to 1984, Unremitted profit recorded the highest average net flows in Nigeria, followed by trade suppliers’ credit. Other foreign liabilities took the third position followed by changes in foreign share capital. The average net flows of liabilities to head office was very insignificant. Between 1985 to 1989, Unremitted profit increased by 115 percent while Trade suppliers’ credit went up by 211.,5 percent and took the lead in this period. Liabilities to head office and changes in foreign share capital recorded remarkable positive changes. Liabilities to head office increased by 517.7 percent while changes in foreign share capital increased at the rate of 270 percent. Other foreign liabilities took a negative turn at -66 percent.

| Table 4.1. The Structure of Capital flow in Nigeria from 1980 – 2010 (N Million) |

| Figure 1. Graphical Representation of Average Net Flow (The Structure of Net Capital flow in Nigeria). Source: obtained from table 4.1 |

| Figure 2. Representation of Average Net Flow in chart (The Structure of Net Capital flow in Nigeria). Source: obtained from table 4.1 |

4.2. Sectoral Distribution of Capital Inflows in Nigeria

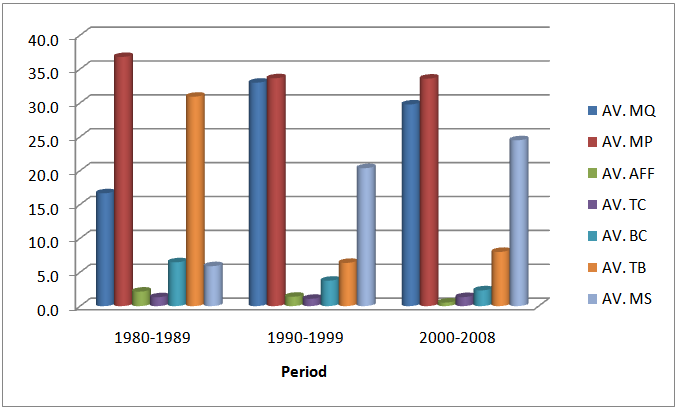

- Foreign capital is involved in various sectors of the Nigerian economy. The major ones include capital intensive industries like mining and manufacturing. They are equally fairly engaged in labour intensive sectors like agriculture, trading, and services. Virtually, in all cases, the common determinants of sectoral distribution are need for investment capital to develop a particular economic sector, availability of un-used raw materials in some sectors of the economy, need for possession of production technology in some economic sectors, need for managerial and technical skills in some fields and provision of infrastructural facilities in some sectors to stimulate growth (Mkpakan, 2004).Based on the factors earlier mentioned, the sectoral distribution of foreign capital in Nigeria covers mining and quarrying; manufacturing and processing; agricultural, forestry and fisheries; transport and communication; building and construction; trading and business services and miscellaneous services as presented in table 4.2 (CBN Statistical Bulletin, 2008).

|

| Figure 3. Graphical Representation of Average Sectoral Distribution of Inflow in Nigeria. Source: obtained from table 4.2 |

| Figure 4. Representation of Average Sectoral Distribution of Inflow in a chart. Source: obtained from table 4.2 |

4.3. Contribution OF Capital Inflows to Gross Domestic Product

- It is observed that between 1980 – 1984, the average contribution made by capital inflows to Gross Domestic Product in Nigeria was 1.08 percent. It rose to 2.2 percent in 1985 – 1989. In 1990 – 1994, the contribution further rose to 6.00 percent and 7.4 percent in 1995 to 1999. Between 2000 – 2004, it dropped to 3.1 percent and picked up again to 6.75 percent in 2005 – 2008. This observation has shown that foreign capital in Nigeria has impacted positively on economic growth.

4.4. Test of Hypothesis

- H0: Capital flow into Nigeria has no significant effect on the economic growth.H1: Capital flow into Nigeria has significant effect on the economic growth.The estimated equation is expressed as:GDP = D0 + D1(UP)t + D2(CFSC)t + D3(TSC)t + D4(OFL)t + D5(LTH)t +eWhere:

The multiple regression analysis conducted using data in table 4.1 – the structure of capital flows in Nigeria and table 4.3 – Gross Domestic Products (GDP) has provided the results as stated below:GDPN = 223784.383 + 0.991UP–0.096CFSC + 0.111TSC – 0.067OFL – 0.048LTH.R = 0.903R2 = 0.816Calculated ‘F’ value = 20.432Table ‘F’ value = 2.64

The multiple regression analysis conducted using data in table 4.1 – the structure of capital flows in Nigeria and table 4.3 – Gross Domestic Products (GDP) has provided the results as stated below:GDPN = 223784.383 + 0.991UP–0.096CFSC + 0.111TSC – 0.067OFL – 0.048LTH.R = 0.903R2 = 0.816Calculated ‘F’ value = 20.432Table ‘F’ value = 2.64

|

5. Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Summary

- This study set out to examine the role of foreign capital inflow on entrepreneurial development in Nigeria. The specific objectives examined include the structure of capital inflows into Nigeria, the distribution of the inflows, the contribution of the inflows to economic growth.Finding has revealed that growth pattern of most of the components of capital inflows into Nigeria was unstable. This resulted to decline in contribution of foreign capital to economic growth. Through out the period investigated, it is apparent that agricultural sector was neglected in the distribution of capital inflows. This was in spite of the vast unused resources available for utilization. However, it is observed that capital inflows have contributed positively to economic growth in Nigeria.

5.2. Conclusions

- In the examination of the role of foreign capital inflows on entrepreneurial development in Nigeria, contribution of the foreign capital to economic growth was the yard stick of measurement. It is found that capital inflows contribute positively to economic growth through out the period reviewed. This finding affirms the views of the neoclassical economists about the role of foreign capital on entrepreneurial development. The decline in the contribution as noticed in the trend analyzed could be attributed to instability in the trend of the inflows as observed in the study.Also this work has affirmed the positions of various empirical literature in Nigeria as reviewed in this study on the relationship between foreign capital inflows and productivity, entrepreneurship and economic growth.

5.3. Recommendations

- 1. It is recommended that government should reemphasize implementation of existing regulations that could attract foreign investments. 2. It is also recommended that government should make provision for special package of recognition to foreign investors that have reached a certain target of investment in Nigeria. 3. Government should make regulations that could attract inflows into agricultural sector. Tax free policy should be applied for agricultural inputs and outputs. 4. Components of inflows such as un-remitted profit; changes in foreign share capital; trade and suppliers’ credit and external borrowing should be encouraged more than inflows in portfolio investments. Investigation has shown that foreign capital in the form of portfolio investments are easily exposed to danger of being terminated in case of economic crisis in the recipient country. 5. Entrepreneurs, particularly, in the informal sector of the Nigerian economy should be assisted by government to obtain loans from international commercial lenders to boast their entrepreneurship.6. Aids and grants to Nigeria for economic development from developed economies should be utilized in financing the informal sector to enhance performance of entrepreneurs vis-à-vis economic growth and development of Nigeria.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML