-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2014; 3(2): 132-139

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20140302.10

Financial Security Laws as an Antifraud Mechanism: Asset or Impediment to the Attractiveness of Exchanges? The Case of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

Félix Zogning Nguimeya1, Pascal Bayl Balata2

1Departement of Accounting Sciences, Université du Québec en Outaouais

2Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

Correspondence to: Félix Zogning Nguimeya, Departement of Accounting Sciences, Université du Québec en Outaouais.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This article examines the overall effectiveness of financial security laws as a means of preventing fraud in the context of the SarbanesOxley Act (SOX), adopted following the financial scandals in the United States. The results show that while this legislation reduced fraud by establishing high governance standards, it also reduced the attractiveness of American financial markets and their ability to raise capital. Foreign companies prefer to list on less regulated exchanges.

Keywords: Sarbanes-Oxley act, Financial security act, Stock market, Governance, IPO

Cite this paper: Félix Zogning Nguimeya, Pascal Bayl Balata, Financial Security Laws as an Antifraud Mechanism: Asset or Impediment to the Attractiveness of Exchanges? The Case of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 3 No. 2, 2014, pp. 132-139. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20140302.10.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The financial scandals that plagued the United States of America in the early 2000s, and the ENRON and WORLDCOM cases in particular, both of which involved the firm of Arthur Andersen (one of the five largest audit and consulting firms), uncovered significant financial and accounting manipulation that was viewed with indifference by specialized media and financial analysts, thus undermining the supposed efficient market principle.The logical outcome of these events, which revealed material problems of internal control, professional conduct, independence and ethics among preparers of financial reports and auditors and other financial analysts alike, was a loss of confidence by investors in the security of financial markets. This prompted American authorities to substantially strengthen regulatory provisions in an effort to counter this major crisis in confidence and the fraudulent practices (Asthana and al, 2009). The Public Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002, commonly known as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, was enacted. The Sarbanes-OxleyAct (SOX) is the most important reform that US financial markets have undergone since the enactment of the Securities Act in 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act in 1934.

2. Provisions of Sarbanes-Oxley

- Adopted with the end goal of reestablishing transparency in financial markets and rebuilding the confidence of investors and small savers, SOX was guided by three major principles: the accuracy and accessibility of information, the responsibility of managers and the independence of audit bodies (Rioux, 2003). Following these guidelines, the main recommendations were as follows (Bédard et al., 2007):• Creation of thePublic Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB)Standards (section 103)Quality control, investigations and sanctions (sections 104-105)• Auditor independenceOther services (section 201)Audit partners (section 203)• Corporate responsibilityAudit committee (section 301)Financial reports (section 302)Internal control (section 302)• Enhanced financial disclosuresManagement assessment of internal controls (section 404)Code of ethics for senior financial officers (section 406)Audit committee financial expert (section 407)While auditor independence and creation of the PCAOB does not appear to have been controversial, the same is not true for the two other main provisions of SOX: enhanced management responsibility and the requirement to establish and assessa reliable internal control mechanism to ensure enhanced financial disclosure. These recommendations (prescribed by sections 302 and 404 of SOX respectively) are considered draconian and are still subject to major debate some 10 years after the law’s adoption and enactment.It was these two provisions that sparked strong negative reaction to SOX when it was introduced. A number of firms criticized the administrative burden that it imposed on them, fearing a drop in productivity and excessive costs. Companies had to commit enormous resources (personnel, time, money, knowledge) to ensure compliance. The law led to many changes that might at first glance appear counterproductive (documentation, controls and testing). Moreover, numerous corporations claimed that producing the financial information required by SOX would be very expensive given the need to put in place a reliable internal control mechanism and to carry out assessments to prove the effectiveness of that mechanism.Although supporters of SOX can congratulate themselves for having imposed on managers of listed corporations and their auditors a degree of formalism never before seen, considerably reducing fraud and restoring a climate of confidence in financial markets, it is important not to overlook the fact that the supplementary costs arising from the SarbanesOxley Act, related primarily to the establishment of internal control procedures associated with financial information disclosure, are considerable and have prompted some companies, mainly foreign ones with modest market capitalization, to reconsider their presence in financial markets.

3. Costs Associated with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

- The Sarbanes-Oxley Act does not only affect American companies. Since the legislation applies to all companies listed in the United States and with revenue greater than $75 million, compliance with SOX rules can become a distinctive element in relations between companies (clients, suppliers) or with US investors and, sometimes, even for companies that are not directly within the scope of SOX’s application (Xavier Paper, 2005; Litval, 2006; Berger and al, 2006).Some companies without the means to comply with the new burdens of the regulations chose to delist. The soaring costs were confirmed by an informal survey conducted in May 2003 by the professional association, Financial Executives International, which was repeated by Paper (2008) with 83 listed companies with revenues of over $3.27 billion. [Translation] “The companies interviewed reported that they were required to devote an average of 6,700 hours to the assessment and improvement of their internal control procedures and an average of an additional $480,000 for audit software services, external consulting and employee training. These companies also anticipated a 35% increase in audit fees associated with the cost of their certification of management’s assessment of internal controls. Representation on boards of directors was also being reconsidered. It is no longer unusual for directors to resign from their positions given that exercising their current mandate is fraught with more disadvantages than advantages.”In light of this situation, many today believe that the drastic requirements imposed by SOX on US listed companies are making American financial markets less attractive than European markets, which may ultimately impact the liquidity of the American market. This is reinforced by the findings of Ayayi & Noël (2007) and Hostak & al (2013) showing that the high costs arising from SOX and the penalties imposed on managers who violate the regulations are encouraging a growing number of companies to deregister from the US exchange in favour of less regulated exchanges. It is therefore quite natural to ask the following question: Will the desire to protect investors lead the US legislator to contribute to reducing the attractiveness of the US financial market?The purpose of our study is to assess the impact of the SarbanesOxley Act as an antifraud instrument on the attractiveness and efficacy of American financial markets, in the context of the evolution of listings and delistings on the various markets in terms of the number of companies and volume of capital, and also, the degree of commitment of investors who, it must be remembered, determine by their invested savings the success of a given financial market.

4. Specific Constraints of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

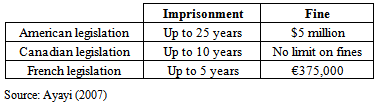

- There are notable similarities and differences between the regulatory reforms introduced in the United States, Canada and Europe. Although SOX is the model used by a number of western countries to develop their own financial security regulations, it should be noted that Europeans and Canadians significantly relaxed certain provisions enacted under the US legislation.Despite differences in the provisions relating to new disclosure requirements on listed companies and the operation of the audit committee, which most European nations, and notably France, did not want to establish as a legal obligation, SOX prescribes the personal responsibility of chief executive officers (CEO) and chief financial officers (CFO) for the quality and reliability of financial disclosures (Kang and al, 2010; Adams, 2012), and substantially increases the penalties for financial offences, as is evident from the table below comparing the American, Canadian and French legislation.

|

5. Results

5.1. Evolution of Initial Public Offerings on US Financial Markets

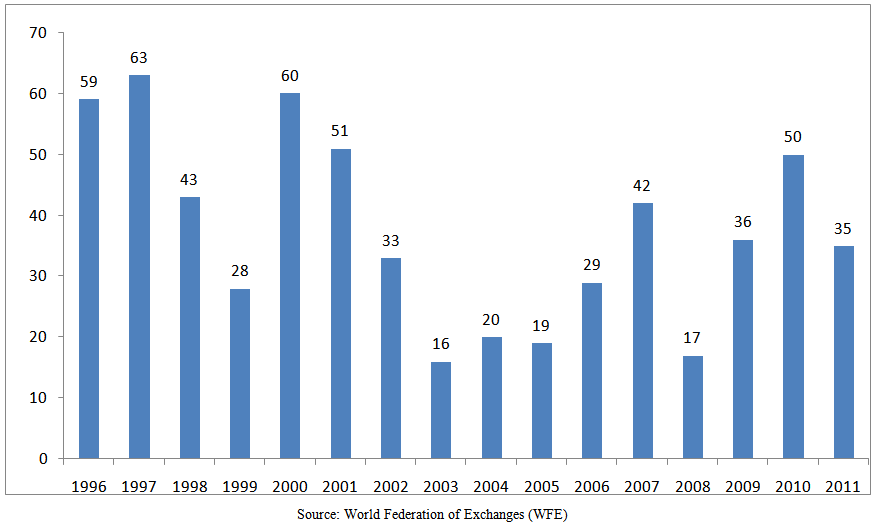

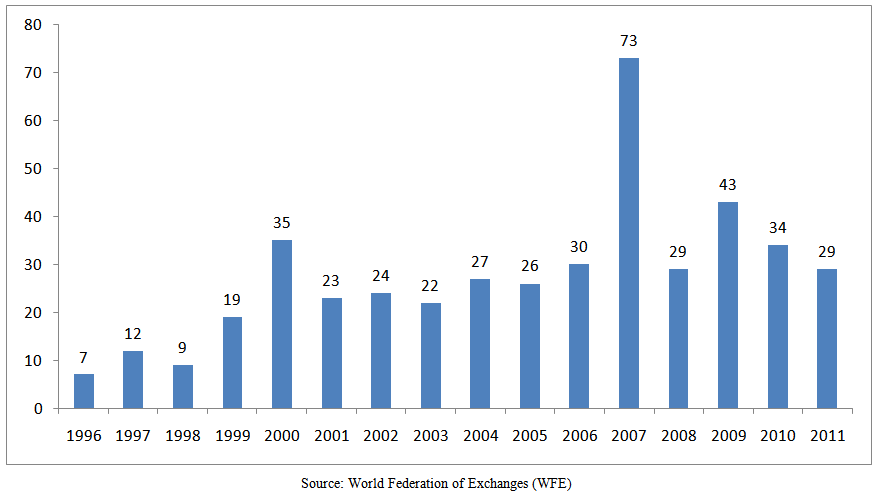

- One of the most detectable variables explaining the evolution in financial markets is the overall trend in the global economy. Between 2000 and 2003, most financial markets experienced a notable decline in the number of initial public offerings following the collapse of the high tech speculative bubble. However, 2004 marked the gradual recovery in initial offerings in most markets, some with stronger and faster gains than others; the US financial markets were among those that experienced a weak recovery. The president of a Dutch company mentioned in the survey by Russell Reynolds Associates stated after the enactment of SOX that [translation] “today’s global markets are very efficient and thus the need for an American listing has declined. European companies will not automatically invest in American capital markets, and American companies might choose to list in countries with weaker regulation.”This prediction is a fairly accurate reflection of the facts, as illustrated in the following graphs:During the first half of the 2000s, fewer and fewer foreign enterprises chose to list on American exchanges. In 2000, 60 foreign companies chose the United States, but the nosedive continued until, in September 2007, only four foreign companies had chosen to list their securities on NASDAQ or the New York Stock Exchange, and did so with no increase in capital. The exchanges ended the year at 42 following measures taken to ease SOX, as we will see later.After the initial version of SOX was enacted, foreign companies not only chose to remain outside the US markets but many that had joined chose to leave. Figure 2 shows the number of foreign companies that delisted from the New York Stock Exchange, a number that increased steadily. From 12 in 1997 (3.9% of all foreign companies listed), the number rose to 30 in 2006 (6.6% of all foreign companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange).

| Figure 1. Listing of foreign companies on American markets, number per year |

| Figure 2. Delisting of foreign companies on the New York Stock Exchange, number per year |

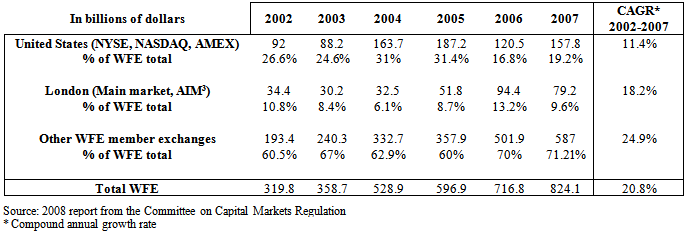

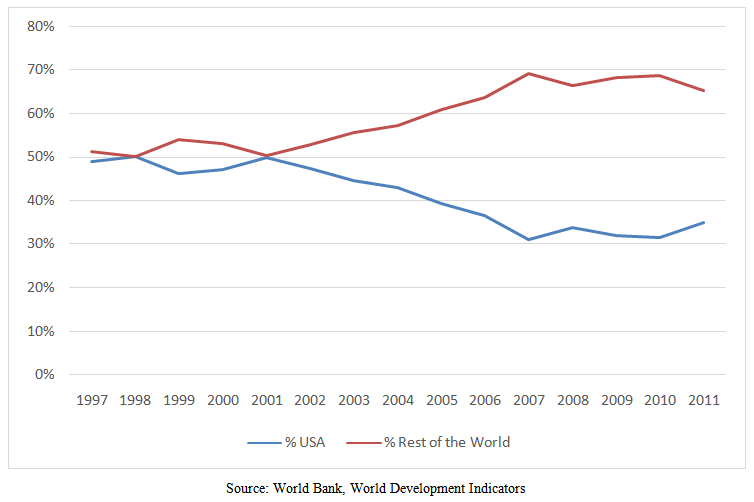

5.2. Capital Raised on Financial Markets: The United States’ Share

- In addition to the number of companies listed and the number delisted on US exchanges since the enactment of SOX, we also look at the level of capital raised on American financial markets (primary and secondary) during the 20022007 period, a period deemed critical for US exchanges in light of the application of SOX in its initial version.The portion of capital raised by American exchanges on global public markets, through public offerings and transactions on the secondary markets, is a useful measure of competitiveness. It reflects the relative interest of US public opinion in the domestic market as well as in foreign issuers. The United States lost significant market share as the table below shows:The rivalry between London and New York as the epicentre of world finance was rekindled during the past decade, notably during the depths of the 20082009 financial crisis. In the above table, we compare the evolution in the liquidity of US markets with that of other WFE member markets, as well as with that of the London Stock Exchange, their main competitor.The United States’ share has fallen sharply since 2005, while that of the rest of the world, after a period of relative stability, has increased substantially. The Unites States still maintains its advantage over Great Britain, the gap between their shares widening by six percentage points between 2006 and 2007 (Table 2) as a result of a decline in London’s share. However, over the period as a whole, the rate of growth in capital raised was only 11.4% for the United States compared to 18.2% for Great Britain and 24.9% for the rest of the world. In other words, the downturn experienced by London investments benefitted the rest of the world more than the United States.

|

|

|

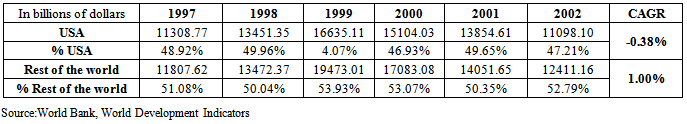

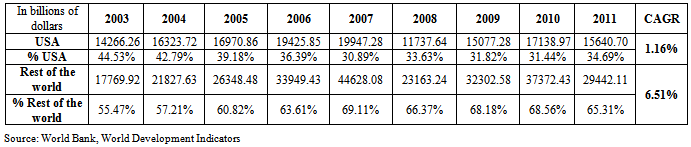

6. Growth in Market Capitalization on American and International Markets

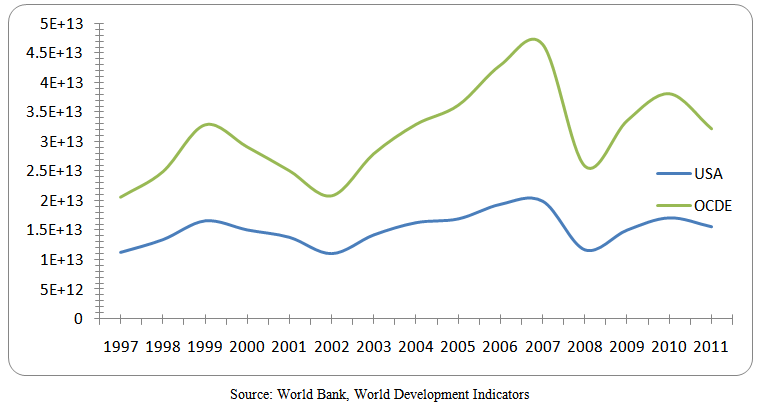

- The evolution in market capitalization is an indicator of liquidity and the depth of a financial market and, in particular, its ability to drive the economy or sustain growth.After considerable growth up to 2000, the level of market capitalization in the United States fell substantially after the high tech speculative bubble burst, as is evident from the figures for 2001 and 2002. A slight recovery occurred throughout the world in late 2003, but growth in the United States was less robust compared to elsewhere (compound annual growth rate of 1.16% compared to 6.51%).

6.1. Growth in Market Capitalization on American and OECD Markets

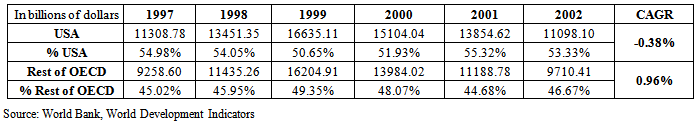

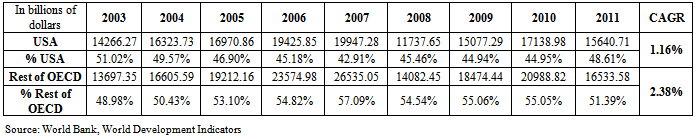

- Between 2000 and 2010, emerging and developing countries experienced much greater growth than most wealthy countries, and numerous financial markets developed in Asia in competition to exchanges in the western world. In an effort to determine whether or not the observed slowdown in US markets is reflective of the situation facing all developed economies, we will now look at the evolution in market capitalization in the United States in relation to that of other developed countries of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development).Tables 5 and 6 show that although the United States’ share within the OECD remained at over 50% until 2003, it declined steadily from 2004 to 2010. Moreover, despite the arrival of the Asian Dragons, the remaining OECD countries experienced stronger market capitalization growth than the United States markets (CAGR of 2.38% compared to 1.6%).

|

|

| Figure 3. Evolution in market capitalization on American and international markets |

7. Conclusions

- In light of the managerial correctness it promises and its focus on different corporate governance and profitability mechanisms, the SarbanesOxley Act was able to guarantee elite status to the companies subject to its provisions. Moreover, these companies saw their market value grow between 15.7% and 34% according to rating agencies (Switzer, 2007).On the down side, the competitiveness of the United States’ financial markets has deteriorated considerably in recent years. From 2006 to 2007, most aggregates continued to decline or did not improve significantly, a trend that had a substantial negative impact on the activity of US financial markets, including the effective generation and allocation of capital. The number of enterprises interested in listing on US exchanges remained quite low, along with the capital raised with initial offerings, and the number of enterprises wanting to delist at the first opportunity grew steadily during the initial years of SOX enforcement.With market capitalization growing at a decreasing rate, the share of trading on world exchanges held by American exchanges is eroding further. Despite these observations, it can still be said that US markets have not experienced as much delisting of foreign companies as expected in recent years. This is due to the exit barriers created by SOX that required any foreign company wanting to withdraw from the US market to prove that fewer than 300 of its shareholders were Americans. This barrier to delisting may also have led to a reduction in initial offerings with companies worried about being trapped and forced to remain listed.On March 21, 2007, in an effort to restore some attractiveness to the US market and enable it to remain competitive, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) approved an easing of the legislation to facilitate delisting of foreign companies. Henceforth, they would have to demonstrate that transactions on the American market represented less than 5% of the average daily volume observed over the previous 12 months on all exchanges on which the company was listed. This explains what has happened since 2007, which amounts to somewhat of a balance between the number of newly listed companies and those delisted, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. Freed from delisting requirements, a number of enterprises were able to leave the exchange, but they were offset by an increase in initial offerings driven by the possibility of being able to delist more easily. Further, on May 23, 2007, the SEC adopted measures easing section 404 of SOX with respect to implementation of an internal control system. This change is partially responsible for the improved market capitalization observed after 2008 (Tables 4 and 6).

| Figure 4. Evolution in market capitalization on American and international markets |

Notes

- 1. Report of the Conseil d’analyse économique, 2007.2. How CFOs are managing changes in roles and expectations, February 2006.3. Alternative Investment Market.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML