-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2013; 2(6): 326-330

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20130206.05

Effects of Strategic Tax Behaviors on Corporate Governance

Fakile Adeniran Samuel, Uwuigbe Olubukunola Ranti

Department of Accounting, College of Development Studies, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Fakile Adeniran Samuel, Department of Accounting, College of Development Studies, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The interactions between corporate governance and taxation are bilateral and biunique: in fact, on one side, the manner in which corporate governance rules are structured affects the way a corporation fulfills its tax obligations; on the other hand, the way tax designs (from the government perspective) and related tax strategies (from the corporation perspective) are planned influences corporate governance dynamics. For example, allowing corporations to keep two different and separate sets of books (one for accounting purposes, the other for tax purposes) makes it easier for tax managers to obtain both tax savings and promising financial statements even though a critical financial status is present. Therefore, the purpose of this research is to analyze the connection between corporate governance and strategic tax behaviors, investigating how corporate governance rules can reach a higher level of corporate compliance with the tax system.

Keywords: Corporate Governance, Tax Behavior, Tax Compliance, Tax Designs

Cite this paper: Fakile Adeniran Samuel, Uwuigbe Olubukunola Ranti, Effects of Strategic Tax Behaviors on Corporate Governance, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 2 No. 6, 2013, pp. 326-330. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20130206.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- When ([1]) launched the study of the agency problem (that managers appointed by shareholders may pursue their own interests) in the corporate setting, they were inspired by the role of taxes in diffusing ownership in the American economy (e.g.[2]). This link between corporate governance and taxation has been neglected in subsequent decades as the study of these two important features of an economy became segregated. Corporate finance scholars have treated taxes only as market imperfections that influence capital structure and dividend policies, while public finance scholars have not incorporated the possibility of agency problems in their analyses. An emerging literature suggests that revisiting this link can generate new insights into the real effects of tax policies and the workings of corporate governance. The rediscovery of this link has been spurred by two developments. First, rising concerns over the proliferation of corporate tax shelters has led to greater interest in the mechanics and motivations for such transactions especially in the context of growing concerns about managerial malfeasance (e.g.[3];[4]).A good corporate governance environment can be achieved by policy makers through direct regulatory action or through tax laws. Tax law has three different objectives: (i) increasing the revenue for necessary governmental functions, (ii) redistributing wealth among the society and (iii) influencing specific behaviors. Tax laws may also have unexpected consequences, a tax provision with the mere objective of increasing the revenue of a specific country may also indirectly influence the behavior of certain individuals or entities (e.g.[5]). Therefore, tax laws can influence corporate governance dynamics directly (as a direct consequence of specific tax policy choices) or indirectly (as an indirect consequence of the way the tax system operates).

1.1. Corporate Governance and Taxation

- Sholes et al. ([6]) confirm that the state although not an investor shareholding companies, has a direct interest in the administration and the maintenance of good corporate governance by companies.[7], in a literature review on agency theory, corporate governance and taxation, assert that the tax system can mitigate or amplify the corporate governance problems. But the inverse can also happen, where the nature of the corporate governance environment can influence the nature and consequences of the tax system. For many years the themes of taxation and corporate governance were considered antagonistic in the literature, but recent studies have concluded that they are related themes, since some corporate governance mechanisms have an important influence on firms’ taxation. They pointed out the impact of tax systems on corporate ownership patterns, and how ownership patterns in turn constrain corporate taxation. They also describe how tax systems are increasingly influencing corporate decisions. [8] studying 51 American companies that had been penalized by the Internal Revenue Service for using tax shelters (through various offshore havens) and also had strong corporate governance tools, found that active tax shelter firms with strong corporate governance exhibit positive abnormal return performance while tax shelter firms with poor corporate governance exhibit significantly lower abnormal returns. [9] present some considerations on tax management and planning of companies in the effort to maximize profits and thus raise firm value. He asserted that companies need to take a holistic view of tax planning by considering all the effects rather than just immediate lowering of the tax liability because of the high tax burden. According to him, the best way for firms to maximize their value is to comply with tax rules and focused on their core business rather than just seeking to lower their taxes.

2. The Use of Tax Laws as a Regulatory Tool for Corporate Governance

- The use of tax laws instead of direct regulations allows the government to rely on an existing and established system (the tax system). The costs incurred by governments to slightly modify an existing and established system would be lower than the costs needed to create, manage and administer a new system (the regulatory system). In other words, the administrative costs incurred by governments would be higher for putting in place a new regulatory system compared with the alternative of utilizing an existing tax system. Moreover, the fact that governments can rely on a well known system is likely to increase the effectiveness of the process since the impact of tax rules on corporate governance dynamics would probably be faster than that of direct regulations. New direct regulations would require governments to create a new system for the implementation and supervision of the new regulations (e.g.[10]), increasing administrative costs and delaying the impact on corporate governance.Compliance costs would be less using pre-existing tax laws, since tax provisions are considered as less complicated than other provisions, because they are already established and thus known (e.g.[10]). Second, the use of the tax system rather than a regulatory system would promote the private decision making process of individuals. In fact, while the use of tax laws (and more specifically of tax expenditures) would give a choice to taxpayers whether to comply with the policy request of the governments or not, direct regulations would not leave such choice to taxpayers, but to the government, favoring a government-centered decision making process.

2.1. The Influence of Corporate Governance Rules on Tax Planning

- There are three reasons why public shareholders may not want managers to engage in strategic tax planning:1. In order to reduce risks of legal challenges and penalties, any transaction that does not have a real business purpose and is designed solely to avoid taxes has to be mischaracterized and obscured by managers. These opaque transactions make it harder for outside investors (current and future shareholders and bondholders) to control insiders (managers). Utilizing opaque transactions, smart tax managers may easily behave opportunistically maximizing their profits and causing extra costs unseen by the shareholders. As a result, corporate governance rules that do not guarantee strong transparency can benefit the private interests of mangers to the detriment of shareholders. The vice versa is also true: under good corporate governance rules which grant transparency, it is more difficult to shelter taxable income. Thus, better corporate governance can reduce tax avoidance.2. The interest of investors in corporate social responsibility has extremely increased in recent years. Public investors seem to be interested in ethical behaviors of corporations. Therefore, good corporate governance which grants alignment of interests and transparency would prevent managers from engaging in strategic tax behaviors.3. [11] has suggested that corporations should always behave as if they are risk-neutral, even if shareholders are not, because shareholders have already diversified the risk by holding diversified portfolios based on the assumption that corporations are risk-neutral.Therefore, an alignment of interests, given by good corporate governance principles, would induce managers to behave as risk-neutral persons managing the corporation’s business.

3. The Definition of Strategic Tax Behaviors: Tax Evasion, Tax Avoidance and Licit Savings of Taxes

- For the purpose of this study, strategic tax behaviors (or aggressive tax planning strategies) are all those actions designed solely to minimize corporate tax obligations whose legality may be under doubt. Three categories of tax behaviors can be identified: tax evasion, tax avoidance and licit saving of taxes (e.g.[12]). Tax evasion can be synthetically defined as intentional illegal behavior, (behavior involving a direct violation of tax law, in order to escape payment of taxes). Licit saving of taxes can be defined as commonly accepted forms of behaviors which are neither against the law nor against the spirit of the law. Tax avoidance can be defined as all illegitimate (but not necessarily illegal) behaviors aimed at reducing tax liability which do not violate the letter of the law, but clearly violate its spirit. The scope of each of these concepts varies from country to country depending on government’s policies, court decisions, tax authorities’ attitudes and public opinion. In this study, strategic tax behaviors are therefore all behaviors identified as tax evasion or tax avoidance.

3.1. Transfer Pricing and Illicit Capital Flight

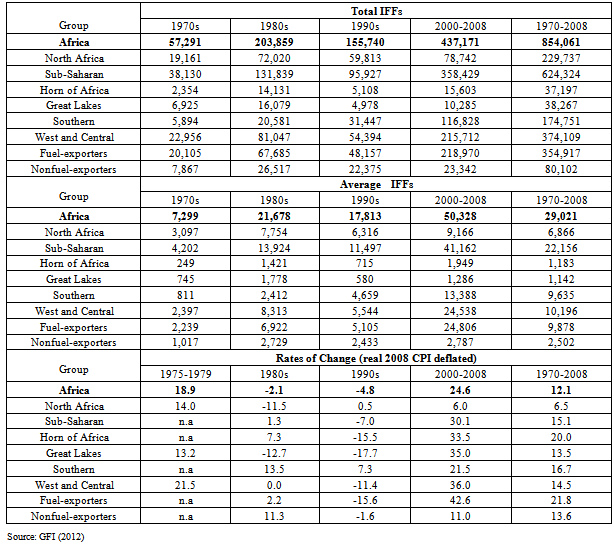

- The extent to which international financial liberalization has facilitated capital flight to onshore and offshore financial centre is an important concern for many countries, developed and less developed. The Tax Justice Network has estimated that capital flight from all countries, including funds undeclared in the country of residence, is approximately US$11.5 trillion (e.g.[13];[14]). Annual global income from such sources is conservatively estimated at US$860 billion, and the annual world‐wide tax revenue lost is approximately US$255 billion, which equals the funds estimated to meet the UN Millennium Development Goals (e.g.[14]). Africa’s cumulated stock of capital flight for 1970–2004 has been estimated at USD 607 billion, representing almost three times the continent’s external debt. The extent of the problem varies from country to country (e.g.[15];[16]). Employing a different method,[17] arrive at a figure of USD 854 billion for the period 1970–2008. Illicit capital flight can be reasonably estimated to be twice the level of aid flows. It is hard to see how effective investment in productive capacity can take place as long as such vast amounts are being squandered by the region’s elites. In many countries, particularly in Sub‐Saharan Africa and Latin America, capital flight has been accompanied by increases in foreign borrowing which means , increased indebtedness has been used not to finance investment or even consumption, but to finance capital flight itself (e.g.[18]). The resulting debt burdens are most likely to hurt the poor, as social spending and infrastructural spending needs to be cut in the face of debt repayments. Estimates presented in Table 1 below show that over the 39-year period Africa lost an astonishing US$854 billion in cumulative capital flight—enough to not only wipe out the region’s total external debt outstanding of around US$250 billion (at end of December, 2008) but potentially leave US$600 billion for poverty alleviation and economic growth. Instead, cumulative illicit flows from the continent increased from about US$57 billion in the decade of the 1970s to US$437 billion over the nine years 2000-2008 (e.g.[19]).

|

- While the overwhelming bulk of this loss in capital through illicit channels over the period 1970-2008 was from Sub-Saharan African countries, there are significant disparities in the regional pattern of illicit flows. For example, capital flight from West and Central Africa, by far the dominant driver of illicit flows from the Sub-Saharan region, on average, fuel exporters including Nigeria lost capital at the rate of nearly $10 billion per year, far outstripping the $2.5 billion dollars lost by non-fuel primary commodity exporters per year. Annual average rates of illicit outflows from Sub-Saharan Africa registered a sharp increase in the 9-year period 2000-2008 relative to the earlier decades. On average, fuel exporters including Nigeria lost capital at the rate of nearly $10 billion per year, far outstripping the $2.5 billion dollars lost by non-fuel primary commodity exporters per year. Table 1 also shows that real illicit flows from Africa grew at an average rate of 12.1 percent per annum over the 39-year period. The rates of outflow in illicit capital for West and Central Africa (14.5 percent) as well as Fuel-exporters (21.8 percent) over the entire period 1970-2008 reflect substantial outflows from Nigeria and Sudan.

3.2. Better Corporate Governance with a General Anti Avoidance Principle

- In the absence of an anti-tax avoidance provision and, in general, in the absence of strong tax enforcement policies, both managers and shareholders seem to have an advantage in engaging in aggressive tax planning. On the contrary, a general anti-avoidance rule, as well as other strong tax enforcement policies, would lower the return to tax avoidance strategies and would guarantee a higher level of transparency in the corporate governance dimension. Moreover, the higher transparency would reduce the amount of income diversion, private benefits and would reduce the agency costs. In other words, since strategic tax behaviors reduce tax revenues and have a negative impact on corporate governance, an anti-avoidance rule may have a positive impact not only on tax compliance (i.e. guaranteeing a higher level of compliance with the tax system), but also on corporate governance (since it would grant lower information asymmetry between managers and shareholders and therefore lower agency costs and higher level of disclosure of information).

4. The Way Forward

- The capability to detect fraud or evasion is crucial to tax compliance. As it would not be practical to audit all cases, the fear of being caught would be sufficient to act as a deterrent. Tax officials should be exposed to adequate and continuous training; both at home and abroad, for a better understanding of recent domestic and international tax issues, which could then be utilized, to formulate successful tax compliance strategies. The working conditions of tax officials also need to be improved in order to motivate them to carry out their duties in a more efficient and professional manner. Much can be gained from studying how different countries have coped with tax reform: the solution reached may be different, but the basic problems that must be faced are often rather similar. Comparative analysis of tax reform experience around the world may not provide a complete answer for any particular country, but it can help.

5. Conclusions

- The historic divide between the study of taxation and the analysis of corporate governance appears to have obscured many fertile areas of research. While some issues at the intersection of taxation and corporate governance have received renewed attention in recent years (primarily due to a concern with tax shelters and managerial malfeasance), taxation can also have significant implications for the various mechanisms that have arisen to ameliorate governance problems. In particular, the impact of tax systems on corporate ownership patterns, and how ownership patterns in turn constrain corporate taxation, appears to warrant further analysis, especially in an international and comparative setting.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML