-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2013; 2(4): 214-219

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20130204.04

The Application of the Accounting Concept of Materiality in the Italian Listed Companies’ Financial Statements

Simone Poli

Department of Management, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, 60121, Italy

Correspondence to: Simone Poli, Department of Management, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, 60121, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The concept of materiality in the process of preparing the financial statement is essentially a matter of disclosure. In fact, financial statement should disclose only the information that are material, namely those that can impact on the decisions of users. However, how concretely to apply the concept of materiality is not generally prescribed by accounting standard setters. As a result, previous studies show that materiality judgements exhibit considerable diversity and remain primarily a matter of professional judgment. This study aims to explore how the concept of materiality has been interpreted and applied in practice by a sample of Italian companies, that adopt the Italian accounting standards, with respect to a set of information that should be disclosed in the financial statements only if they are judged material.

Keywords: Materiality, Disclosure, Financial Statements, Italian Accounting Standards

Cite this paper: Simone Poli, The Application of the Accounting Concept of Materiality in the Italian Listed Companies’ Financial Statements, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 2 No. 4, 2013, pp. 214-219. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20130204.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Materiality is a key concept both in accounting and in auditing. Every national and international accounting and auditing standard setter provides a definition of the term materiality. It results a range of definitions that appear broadly similar (e.g.[1]). However, how concretely to apply the concept of materiality is not generally prescribed. Thus, the application of the concept of materiality results doubtful for both accountants and auditors.This situation has led scholars to investigate what should be judged material and what accountants and auditors judge material when it is not prescribed by any standard (e.g.[2];[3];[4]), mainly aiming to suggest guidances. Our study adds to previous literature on this issue, exploring how the (accounting) concept of materiality is interpreted and applied by Italian accountants in the process of preparing the financial statements.The concept of materiality in the abovementioned process is essentially a matter of disclosure[5]. In fact, financial statements should disclose only the information that are material, namely those that can impact on the decisions of users. An information is material if it is sufficient to change the opinion of an investor about a company.On the one hand, if accountants want to be comprehensive and include all information, financial statements will contain huge unnecessary (not material) information that will mislead the users of the financial statements. In other words,the elimination of immaterial disclosures increases the effectiveness of the remaining disclosures (and reduces the costs of disclosure) ([5]). On the other hand, if accountants fail to disclose material information, they would mislead the users of the financial statements. A first problem is that the perception of materiality of accountants (or auditors, as in[6] and[7]) may differ from that of the users of the financial statements. In this regard, some studies reveal that users of financial statements react to amounts that are much smaller than those that are proposed as heuristic materiality levels (e.g.[8];[9];[10]).An important research question addressed by scholars is whether there is a best method to estimate materiality. In respect to this, studies can be divided into two types[11]. The first includes “experimental” studies, that are based on questionnaires, case studies or games (e.g.[12]). They ask participants to make materiality decisions in an experimental setting. The second includes “historical” or “archival” studies, that are based on the analysis of historical documents such as financial statements (e.g.[7];[13]). The idea behind this second group of studies is that the materiality thresholds used in very specific circumstances can be estimated by reviewing information disclosed in financial statements of various firms. They infer materiality by examining such historical documents.Experimental studies have the benefit of measuring the threshold of materiality directly and the drawback of lacking real world pressures and nuance. Historical studies have the benefit of reflecting what people actually do when confronted with real world pressures and the drawback of requiring inference to impute the materiality thresholds.However, in literature there are also studies that adopt both the study methods (e.g.[14]).Comparing the results that emerge from the two study methods,[11] noted a substantial difference that leads him to be critical of experimental studies.Another important research question addressed by scholars is which quantitative materiality measures to develop materiality thresholds are the best. In other words, which financial statement items are most closely associated with the materiality decision.[15] reveal that four items of the financial statement are found to be strongly associated with materiality. They are: income, revenue, assets and equity. Materiality thresholds based on revenue or assets are more stable from period to period because they tend to fluctuate less than income or equity and they are much less likely to be affected by a small denominator. For example, if income is near zero, a small amount will appear large relative to it.[16] suggest the “blending method” that is based on multiple materiality measures and combines them to make the final decision. Such a method is based on the idea that the materiality decision hinges not on how an item impacts one component of the financial statement but rather how it affects several of them (e.g.[13]).The literature shows that most of the previous studies have been conducted with reference to the United States (e.g.[11]). Other contexts investigated (although very few) are, for example, Australia (e.g.[17]), Denmark (e.g.[18]), Finland (e.g.[19]), Canada (e.g.[20]), United Kingdom (e.g.[21]). Expanding the number and type of contexts is very interesting because it provides important data to assess whether materiality judgments are culturally sensitive. In this perspective, the Italian context has not yet been studied.In Italy, the process of preparation of the financial statement is regulated by the national civil law and can be influenced by the national accounting standards whose main aims are to interpret and integrate the civil law (see[22];[23]). The influence of the national accounting standards is only possible because they are not mandatory for any company.The Italian legislator states that certain information must be disclosed in financial statements only if they are judged relevant and material. However, it does not make a clear distinction between the concepts of relevance and materiality. In fact, the two terms (1) are not defined, (2) are often used interchangeably and (3) both of them mainly relate to the quantitative dimension of certain information. Moreover, it does not consider such concepts in a specific and autonomous way. In fact, they have no place in the list of the general principles of the preparation of financial statement. Finally, it does not give any specific indications of what should be considered relevant and material.In the Italian accounting standard no. 11[24], that sets out and defines the general principles for the preparation of the financial statement, we can read: “Relevance and materiality of the economic facts for the purpose of presentation in the financial statements. The financial statement must disclose only those information that have a relevant and material effect on financial statement data or on the decision-making process of users. The principle of relevance is also reflected in numerous rules relating to the preparation and the content of the financial statement. The process of preparation of the financial statements requires estimates or forecasts. Therefore, the correctness of the financial statement data refers not only to the arithmetic accuracy, but to the economic fairness, the reasonableness, that is the reliable result that is obtained by the application of sound and honest assessment procedures adopted in the preparation of the financial statements. Errors, simplifications and roundings are technically unavoidable and find their limit in the concept of materiality, that is they must not be of such magnitude as to have a material effect on financial statements and their meaning for the users”. The concepts of relevance and materiality, then, are called, sometimes explicitly sometimes implicitly, in the other Italian accounting standards. Therefore, with respect to the civil law, we find the setting out and a partial definition of the concepts under consideration but, for the rest, we can detect the same critical aspects that we have observed for the civil law.Taking into account that in Italy neither the national civil law nor the national accounting standards offer any guidelines for the concrete interpretation and application of the concept of materiality, we aim to explore whether and how the concept of materiality is interpreted and applied in practice by a sample of Italian companies with respect to a set of information that should be disclosed in financial statements only if they are judged material.Our study enriches the literature on how companies behave when the system of rule and accounting standards concerning the preparation of the financial statements give no precise indication on the concept of materiality. In this perspective, the contribution is particularly relevant because the Italian case is not yet explored and because it is not an English-speaking context on which previous studies have mainly focused.Our findings should interest accounting and auditing standard setters, especially those who deliberate on the content of accounting and auditing guidance, both Italian and international, because it points out what could happen when specific guidelines lack.

2. Research Design

2.1. Research Method

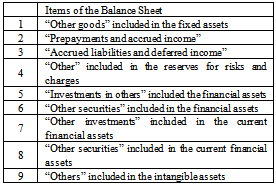

- Our study is based on the “historical” or “archival” research method, carried out through the analysis of financial statements.As said in the introduction, we aim to explore how the concept of materiality is interpreted and applied in practice by a sample of Italian companies with respect to a set of information that should be disclosed in financial statements only if they are judged material (the abovementioned sample is described in the next section). To do so, we observe when the information whose disclosure depends on the materiality judgment have been disclosed or have not been disclosed and deduce how the concept of materiality has been interpreted and applied.In accordance with the Italian accounting standards, certain information (for example, the splitting of an item into its sub-items in the notes) must be disclosed in financial statements only if a quantitative dimension of a certain aspect of such information (for example, the amount of an item of the financial statement) is judged material. As a result, when such information have been disclosed, we can deduce that the abovementioned quantitative dimension has been judged material. Conversely, when such information have not been disclosed, we can deduce that the abovementioned quantitative dimension has been judged not material. Thus, our analysis is focused on the quantitative dimension of the aspect of reference, on the one hand, and on the presence/absence of the information that must be disclosed in the event that such a quantitative dimension is judged material, on the other hand.In accordance with the Italian accounting standards, the cases in which it is necessary to apply the concept of materiality are numerous (see[25]). We limit the investigation to a specific kind of such cases, those in which it is necessary to disclose the details of certain items of the balance sheet in the notes when such items have an amount that is judged material[24]. These cases are listed in Table 1.

|

2.2. Research Sample

- We have used a purposive (or judgmental) sample, namely one that is selected on the basis of the knowledge of a population and the purpose of the study. Such a sample is coherent with the aims of our study that are not to generalize on the results obtained for the sample, but to simply observe the phenomenon under study within the context of the sample itself.The criteria for the sampling are the following.1. Exploring how the concept of materiality is interpreted and applied in the context of the process of preparation of the financial statements in accordance with the Italian accounting standards requires that the sample is made up of those companies to which such standards are directed and, therefore, the sample units have to be chosen from among Italian, commercial, industrial and service companies.2. The Italian accounting standards are not mandatory for any company. However, for those listed in the Italian Stock Exchange, the Italian Companies and the Stock Exchange Commission (CONSOB) has explicitly recommended their adoption. In addition, all of them declare to adopt the Italian accounting standards. Then, the sample units can be selected among the listed Italian, commercial, industrial and service companies.3. Among the listed Italian, commercial, industrial and service companies, it has been decided to choose the 100 largest ones, in terms of capitalization, with reference to 31st December 2004. The data relate to the financial statements referring to the fiscal year ending on 31th December 2004. The reference to such a date depends on the fact that the financial statements ending on that date were the last to be generally drawn up according to the Italian accounting standards. In fact, the companies chosen would have the option to adopt international accounting standards on a voluntary basis for the fiscal year ending on or after 31st December 2005 and it would become mandatory for the fiscal year ending on or after 31st December 2006.

3. Results

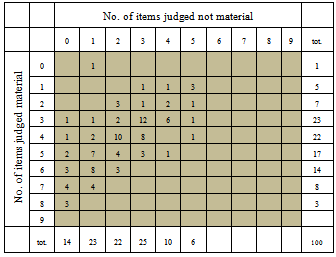

- The financial statements of the companies included in the sample have shown a variable number of the items listed in Table 1. When shown, some of them have been judged material, others have been judged not material. The results of this first analysis is shown in Table 2.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

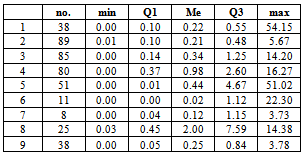

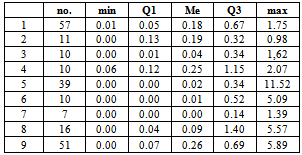

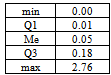

- Table 3 shows that, with reference to all the items listed in Table 1, in a number of cases that appears to be not negligible, the size of the item that has been judged material appears to be really low, often close to 0%.Table 5 shows that in 75% of cases in which a company has judged material at least one item (that corresponds to 75 companies) the minimum (min) judged material has been at most equal to 0.18%.Thus, the data show a tendency to disclose the information subject to the materiality judgment also for the items whose size does not actually appear material. This seems to be at odds with the spirit of the concept of materiality, according to which not material information should not be disclosed in the financial statements since they may compromise the effectiveness of the message conveyed.With reference to each item listed in Table 1, comparing the behavior of the companies that have judged material the item (Table 3), on the one hand, with that of those that have judged not material the same item (Table 4), on the other hand, it results that in many cases a same size of the item has been judged material by some companies and not material by other companies.With reference to the companies that have judged material at least one item and, at the same time, not material at least another item (85), it results that the size of at least one item judged not material is higher than the size of at least another item judged material in 69 cases (we refer to the cases in which the maximum (max) of the item that has judged not material is higher than the minimum (min) of the item that has judged material).Thus, the data show a broadly heterogeneous and contradictory way to interpret and apply the concept of materiality, both with respect to the same item and with respect to the same company. This highlights that there are not prerequisites to detect uniformity, neither external nor internal. Therefore, the concept of materiality, with reference to the companies included in the sample and to the types of information analysed, does not present a uniform method of interpretation and application. Rather, as previous studies reveal, in situations in which mandated materiality guidelines do not exist, as the Italian case investigated in our study, materiality judgements exhibit considerable diversity and remain primarily a matter of professional judgment[26].

5. Conclusions

- Our study has highlighted two main findings related to how the concept of materiality is interpreted and applied by the Italian companies included in the sample with respect to the information observed.Firstly, items that appear to be really low, also close to 0%, have judged material.Secondly, the interpretation and application of the concept of materiality are broadly heterogeneous and contradictory. As concerns all of the types of information reported, it emerged from the research that the behaviour of the various companies included in the sample was, in general, highly variable. In other words, the results showed that the research brought to light neither converging behaviour leading towards uniform practices, nor discriminating quantitative dimensions (threshold values) which lead to disclosure or omission of certain information.What has paradoxically emerged from the research is that the concept of materiality is applied, but it is done in so many diverse ways that it becomes apparently difficult to identify in practice. The intent is there, in theory, but in practice, it can not be found to be concretely applied. That is to say that the concept of materiality is, in effect, more of an ideal than a concrete reality.The main limitations of our study are represented by the fact that it has adopted only a quantitative measure of materiality, ignoring qualitative ones, and by the fact that this measure is only the total assets of the balance sheet. Adopting qualitative measures or a different quantitative measure might have led to different findings.Our study, as previous ones, emphasizes quantitative factors in determining materiality. However, quantifying an item represents only one step in analysing materiality. Materiality decisions require a complete analysis of all relevant factors, both quantitative and qualitative. Some qualitative factors might cause items producing quantitatively small amounts to be considered material. This requires further research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author thanks the professors S. Branciari and S. Marasca for the stimuli received and the two anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML