-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2013; 2(4): 199-210

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20130204.02

Voluntary Corporate Governance Disclosures in the Annual Reports

Madan Lal Bhasin

Department of Accounting & Finance, Bang College of Business, KIMEP University, Abai Avenue 2, Dostyk Building, Almaty, 050010, Republic of Kazakhstan

Correspondence to: Madan Lal Bhasin, Department of Accounting & Finance, Bang College of Business, KIMEP University, Abai Avenue 2, Dostyk Building, Almaty, 050010, Republic of Kazakhstan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Corporate governance (CG) disclosure is a fundamental theme of the modern corporate regulatory system, which encompasses providing ‘governance’ information by a corporation to the public in a variety of ways. The purpose of this research is to examine the CG disclosure practices of Indian corporations at a time prior to when mandatory requirements for disclosure were introduced. Hence, this study explores the voluntary CG practices of 50 corporations, over and above the mandatory requirements of Clause 49 of the Listing Agreement. In order to study the CG disclosure practices, we have prepared a CG Disclosure Index. We have primarily used secondary sources of information, both from the Report on CG and the Annual Reports for the financial year 2003-04 and 2004-05. As a part of this study, a total of 40 items have been selected from the CG section of the annual report for the period of study. In order to provide a comparison across the industries, a sample of 50 corporations have been taken from four industries, viz., software, textiles, sugar and paper. Appropriate statistical tools and techniques have been applied for the analysis of the results. It has been observed that corporations are following less than 50 percent of the items of CG Disclosure Index. Moreover, there is no significant difference among the disclosure scores across the four industries.

Keywords: Voluntary Corporate Governance Disclosure, Annual Report, Clause 49, Disclosure Index

Cite this paper: Madan Lal Bhasin, Voluntary Corporate Governance Disclosures in the Annual Reports, International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 2 No. 4, 2013, pp. 199-210. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20130204.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Corporate Governance (CG) involves a set of relationships between a corporation’s management, its board, its shareholders and other stakeholders. It also provides a principled process and structure through which the objectives of the corporation, the means of attaining the objectives, and systems of monitoring performance are set. Indeed, CG is a set of accepted principles by management of the inalienable rights of the shareholders as a true owner of the corporation and of their own role as trustees on behalf of the shareholders. It is about commitment to values, ethical business conduct, transparency, and makes a distinction between personal and corporate funds in the management of a corporation. However, a detailed and well-structured system of CG disclosures in the annual reports of corporations enables investors to understand, and obtain accurate and reliable information about the corporations in order to make ‘better’ investment decisions[1]. In view of the current economic downturn, CG and disclosure about governance may become a more pressing issue for the listed corporations, particularly if it relates to going-concern reporting, risk management, internal controls, board balance, and directors’ remuneration[2]. It should be noted at the outset that disclosure of information by a Corporation is like a double-edge ‘sword’ in the management hands. Disclosures about the firm’s human resources, risk, and the like, are likely to be effective in reducing information ‘asymmetries’ and mitigating their need for price protection. On the other hand, disclosures about the marketing strategies, R&D, technology, etc., might jeopardize the firm’s competitive advantage. Therefore, by and large, corporations are reluctant to disclose the relevant information which could tarnish their image. Disclosure of information enables the shareholders’ to evaluate the management’s performance by observing, how efficiently the management is utilizing the corporation’s resources in the interest of the principal[3]. Accountability, transparency, fairness, and disclosure are the four “pillars” of the modern corporate regulatory system, and involve the provision of information by corporations to the ‘public’ in a variety of ways. Disclosures can be viewed from two perspectives: corporate disclosure and financial accounting disclosure[4]. Therefore, information and its “true-and-fair” disclosure are the areas where corporation law and accounting regulations join hands together. It is a key objective of accounting rules, in general, to ensure that users’ have sufficient, reliable and timely availability of information in order to participate in the market, on an informed basis[5]. According to the UNCTAD[6] “All material issues relating to CG of the enterprise should be disclosed in a timely fashion. The disclosure should be clear, concise, precise, and governed by the substance over form principle.” However, disclosure requirements can sometime provide a more ‘efficient’ regulatory tool, than ‘substantive’ regulation, through more or less detailed rules. Substantive law, in fact, deals with rights and duties that are not matters purely of practice and procedure. Such disclosures, however, create a lighter regulatory environment and allows for greater flexibility and adaptability. To sum up, disclosure is the ‘foundation’ of any structure of good CG.During the 1990s, a number of high-profile corporate scandals in the USA (viz., Lehman Brothers, AIG Insurance, Xerox, Arthur Anderson, Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, etc.) and also elsewhere in the world, triggered an in-depth reflection on the regulatory role of the government in protecting the interests of shareholders. Thus, to redress the problem of corporate misconduct, ensuring ‘sound’ CG is believed to be essential to maintaining investors’ confidence and good performance. In view of the growing number of scandals and the subsequent wide-spread public and media interest in CG, a plethora of governance ‘norms’ and ‘standards’ have sprouted around the globe[7, 8]. For instance, the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation in the USA, the Cadbury Committee recommendations for the European Union (EU) corporations, and the OECD principles of corporate governance, are perhaps the best-known among these. The Cadbury Committee advocated, first of all, disclosure as “a mechanism for accountability, emphasizing the need to raise reporting standards in order to ward-off the threat of regulation.” Similarly, the Hampel Committee[9] regulated disclosure as “the most important element of accountability and in introducing a new code and set of principles stated that their objective was not to prescribe corporate behaviour in detail but to secure sufficient disclosure so that investors and others can assess corporations performance and governance practice and respond in an informed way.” Well, over a hundred different codes and norms have been identified in recent surveys and their number is steadily increasing. Jamie Allen[10] states that “most of the countries/markets in the Asian region had taken the initiative long-back in 1990s by formulating and implementing an official code of CG,” which is summarized in Table 1 Fortunately, India has been no exception to this rule. In the last few years the thinking on the CG topic in India has gradually crystallized into the development of norms for listed corporations. However, there is no doubt that gradually “improved” disclosure requirements, across all over the world, will ultimately protect the long-term interest of shareholders and all other stakeholders.

2. The Pros & Cons of Making Voluntary Disclosures in Annual Reports

- Voluntary disclosures in the annual reports are disclosures that are not required explicitly by law or by other regulations. According to agency theory, the separation of ownership and control creates information asymmetries due to the misalignment of managers and shareholders’ interest. Information asymmetries may create a transfer of wealth from owners to managers, leading current and potential investors to discount share prices if there is not a proper financial disclosure. In order to control and reduce the costs of the agency relationship, control mechanisms must be considered to ensure that managers act in the interests of the owners impeding the expropriation of investors’ resources by managers. Information transparency through voluntary disclosures and the structure of corporate boards have been considered as two of the main documented mechanisms that significantly affect the control and monitoring role of the governance process, reducing the costs that result from information asymmetries related to the agency relationship.

|

3. Clause 49 of the Listing Agreement

- The term ‘Clause 49’ refers to clause number 49 of the Listing Agreement between a corporation and the stock exchanges on which it is listed (the Listing Agreement is identical for all Indian stock exchanges, including the NSE and BSE). This clause was added to the Listing Agreement in late 2000 consequent to the recommendations of the Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee on Corporate Governance constituted by the “Securities Exchange Board of India (SEBI)” in 1999. Clause 49, when it was first added, was intended to introduce some basic CG practices in Indian corporations and brought in a number of key changes in governance and disclosures (many of which we take for granted today). “It specified the minimum number of independent directors required on the board of a corporation. The setting up of an Audit committee, and a Shareholders’ Grievance committee, among others, were made mandatory as were the Management’s Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) section and the Report on Corporate Governance in the Annual Report, and disclosures of fees paid to non-executive directors. A limit was placed on the number of committees that a director could serve on”[21]. In late 2002, the SEBI constituted the Narayana Murthy Committee to “assess the adequacy of current corporate governance practices and to suggest improvements.” Based on the recommendations of this committee, SEBI issued a modified Clause 49 on October 29, 2004 (the ‘revised Clause 49’) which came into operation on January 1, 2006.The revised Clause 49 has suitably pushed forward the original intent of protecting the interests of investors through enhanced governance practices and disclosures. Five broad themes predominate: the independence criteria for directors have been clarified; the roles and responsibilities of the board have been enhanced; the quality and quantity of disclosures have improved; the roles and responsibilities of the audit committee in all matters relating to internal controls and financial reporting have been consolidated; and the accountability of top management (specifically the CEO and CFO) has been enhanced. Within each of these areas, the revised Clause 49 moves further into the realm of global best practices (and sometimes, even beyond). “Similar in spirit and scope to the Sarbanes-Oxley measures in the USA, Clause 49 has clearly been a milestone in the evolution of CG practices in India”[22]. The revised Clause 49 has suitably pushed forward the original intent of protecting the interests of investors through enhanced governance practices and disclosures. No doubt, the quality and quantity of disclosures have improved. Corporate managers and investors agree that while it can be argued that complying with these requirements involves a significant amount of effort, there can be no doubt that these are an essential step towards bringing Indian capital markets and governance standards in line with the rest of the world. Clearly, at least the corporations with best-in-class governance practices (like Reliance, Tata, Hindustan Lever, Infosys, etc.) are setting good examples and steeling themselves for this process. Most of the leading corporations in India have already taken the first steps down this path. Although all of them are concerned about the costs involved, most are aware that this is a process which yields substantial benefits in the long-run as the US experience is beginning to show. India has the largest number of listed corporations in the world, and the efficiency and well being of the financial markets is critical for the economy in particular and the society as a whole. It is imperative to design and implement a dynamic mechanism of CG, which protects the interests of relevant stakeholders without hindering the growth of enterprises. With the SEBI guidelines (Clause 49) demanding the listed Indian corporations to adopt and follow the CG norms, it became necessary for every organization to ensure higher shareholder and stakeholder values. The SEBI envisages that all these CG norms will be enforced through listing agreements between corporations and the stock exchanges. A little reflection suggests that for corporations with little floating stock delisting because of non-compliance is hardly a credible threat. The SEBI can, of course, counter that by stating that the reputation effect of de-listing can induce compliance and, hence, better corporate governance. Thus, what is needed a small corpus of legally mandated rules, buttressed by a much larger body of self-regulation and voluntary compliance. “It is now mandatory for the corporations to file with the SEBI, the CG compliance report, shareholding pattern along with the financial statements. The SEBI has created a separate link known as “Edifar” to post the relevant information submitted by the corporation”[23].

4. Review of Literature

- Across the globe, CG has attracted considerable attention over the past decades, leading to recommended codes of best practice, conceptual models, and empirical studies. There is no denying the fact that transparency is an important component of a well-functioning system of CG. However, corporate disclosure to stakeholders is the principal means by which corporations can become transparent[24].Recently, CG has received much attention in the Asian countries due to its financial crisis. For example, Gupta, Nair and Gogula[25] analysed the CG reporting practices of 30 selected Indian corporations listed in BSE. The CG section of the annual reports for the years 2001-02 and 2002-03 had been analysed by using the content analysis, and least square regression technique was used for data analysis. The study found “variations in the reporting practices of the corporations, and in certain cases, omission of mandatory requirements as per Clause 49.” Bhattacharya and Rao[26] examine whether adoption of Clause 49 predicts lower volatility and returns for large Indian firms, they compare a one-year period after adoption (starting June 1, 2001) to a similar period before adoption (starting June 1, 1998). The logic is that Clause 49 should improve disclosure and thus reduce information asymmetry and thereby reduce share price volatility. The authors find insignificant results for volatility and mixed results for returns. Collett and Hrasky[11] analysed the relationships between voluntary disclosure of CG information by the corporations and their intention to raise capital in the financial market. A sample of 299 corporations listed on Australian stock exchange had been taken for the year 1994 and Connect-four database had been used for collection of annual reports of corporations. The study found out that “only 29 Australian corporations made voluntary CG disclosure, and the degree of disclosures were varied from corporation to corporation.” Similarly, Barako[27] examined the extent of voluntary disclosure by the Kenyan companies over and above the mandatory requirements. This study covered a period of 10 years from 1992 to 2001. The results revealed that “the audit committee was a significant factor associated with level of voluntary disclosure, while the proportion of non-executive directors on the board was negatively associated.” In another study undertaken by Subramanian[28], the author identified the differences in disclosure pattern of financial information and governance attributes. A sample of 90 corporations from BSE 100 index, NSE Nifty had been taken. The data with respect to disclosure score had been collected from the annual reports of the corporations for the financial year 2003-04. The study used the Standard & Poor’s “Transparency and Disclosure Survey Questionnaire” for collection of data. The study finally concluded that “there were no differences in disclosure pattern of public-private sector corporations, as far as financial transparency and information disclosure were concerned.” Similarly, Gupta[29] traced out the differences in CG practices of few local corporations of an automobile industry. The data with respect to governance practices had been collected from the annual report of the corporations for the year 2004-05. The study “did not observe significant deviations of actual governance practices from Clause 49.” Recently, Sareen and Chander[30] examined the relationship between corporation attributes and extent of CG disclosures. Their study used the secondary sources of data taken from 100 selected BSE listed corporations. Also, anindex of CG disclosure, consisting of 85 items, was constructed. Linear regression equation was used for each independent variable separately, and multiple regression analysis for all variables done. The findings of their study exhibit a positive relationship between selected corporation attributes and extent of CG disclosure. The aforesaid review of studies reveals that there is an urgent need to study the “voluntary” CG disclosure practices followed by the corporations in India. Voluminous research work has been carried out to study the mandatory aspect of CG. The study of voluntary CG practices has remained as an untouched phenomenon yet. CG is in the process of evolution, and over a period of time, the scope of mandatory CG is expected to be extended further. Therefore, the study of voluntary CG practices assumes significance at this evolving stage of CG in India. This paper attempts to study the voluntary CG practices followed by the corporations over and above the mandatory requirements. This study has been planned with the following two specific objectives in mind: (a) to examine the voluntary corporate governance disclosure practices of selected companies, and (b) to measure the extent of variation in the disclosure pattern of corporate governance practices of the corporations under study.

5. Significance & Time Period of Study

- In India, the question of CG has assumed importance mainly in the wake of economic liberalization, deregulation of industry and business, as also the demand for a new corporate ethos and stricter compliance with the legislation. However, there have been several leading CG initiatives launched in India since the mid-1990s. The first was by the CII, which came up with the first “voluntary” code of corporate governance in 1998. In 1996, CII took a special initiative on CG—the first institutional initiative in Indian industry. In April 1998, India produced the first substantial code of best practice on CG after the start of the Asian financial crisis in mid-1997. Titled “Desirable Corporate Governance: A Code”, this document was written not by the government, but by the Confederation of Indian Industries (www.ciionline.org). It is one of the few codes in Asia that explicitly discusses domestic CG problems and seeks to apply best-practice ideas to their solution. The next big move was by the SEBI, now enshrined as Clause 49 (very similar to the U.S. Sarbanes-Oxley Act, 2002) of the listing agreement. In late 1999, a government-appointed committee under the leadership of Shri Kumar Mangalam Birla (Chairman, Aditya Birla Group) released a draft of India’s first national code (Clause 49) on CG for listed companies. The code, however, was approved by the Securities Exchange Board of India (SEBI) in early 2000 and was implemented in stages over the following two years (applying first to newly listed and large companies). It also led to changes in the stock exchange listing rules. The Naresh Chandra Committee and Narayana Murthy Committee reports followed it in 2002. Based on some of the recommendation of these two committees, SEBI further revised the Clause 49 of the listing agreement in August 2004. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, an intermediate period of two years from 2003-04 and 2004-05 was found to be most appropriate, and finally, selected.

6. Research Methodology Used

- Voluntary disclosures have been extensively documented across markets, such as in the U.S., U.K. and the Asian region. The purpose of this research is to examine the CG disclosure practices of Indian corporations at a time prior to when mandatory requirements for disclosure were introduced. Hence, for the purpose of this study, we have taken a sample of 50 listed Indian corporations for a period of two years, i.e., 2003-04 and 2004-05. These corporations were selected on the basis of “average” sales for a period of four years starting from 2000-01 to 2003-04. Accordingly, the data with respect to the sales figures were extracted from Prowess database of Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). Ranking method was used for selection of the corporations and the first 15 corporations having highest sales figures have been included in the sample. Hence, the total number of selected corporations was 60, but due to the non-availability of annual reports of few corporations, the sample was finally restricted to 50 corporations. In order to study the voluntary CG practices of the sample corporations, the CG section of the annual report has been analysed. The data with respect to CG practices of the corporations have been collected from the annual reports of the corporations, as well as, Prowess database. Our sample of 50 corporations comprised of corporations drawn from four industries, viz., software, textiles, sugar and paper. Table 2 shows the industry-wise break up of our sample of study.

|

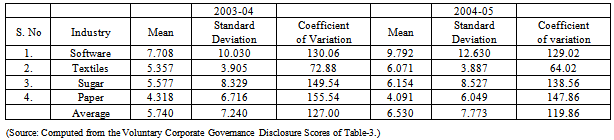

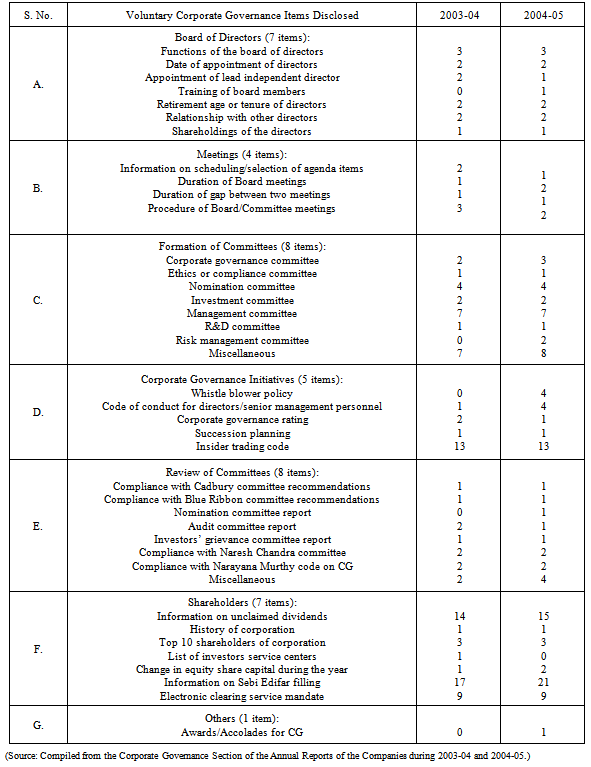

7. Voluntary Corporate Governance Index

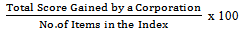

- A voluntary “CG Index” has been prepared by selecting 40 items from the CG section of the annual reports of these corporations. All the items have been divided into seven dimensions, such as, board of directors, meetings, formation of committees, CG initiatives, compliance reports of committees, shareholders and others. Annexure-1 shows the item-wise voluntary CG disclosure score, categorized into seven heads, during 2003-04 and 2004-05. The contents of index have been compared with the voluntary CG practices, if any, followed by the corporation, and awarded a score of 1 for following a particular item, or 0 for otherwise. Descriptive statistics, i.e., mean, standard deviation and coefficient of variation have been applied for the analysis. Moreover, Kruskal-Wallis Test has been applied to see the significance of difference of reporting among the industries.In order to study the voluntary CG disclosure practices of each corporation, disclosure score has been arrived at as follows:Voluntary Governance Score of a Corporation =

8. Analysis of the Results

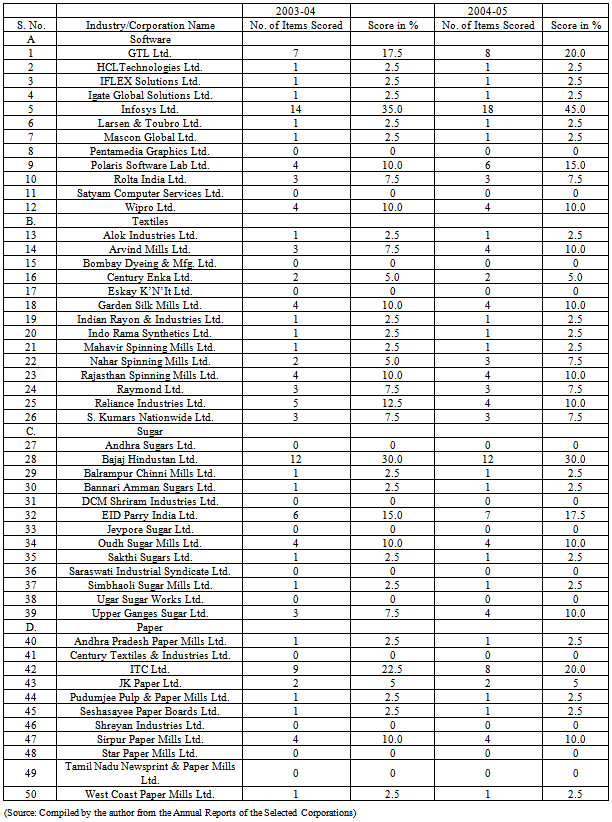

- Table 3 present the corporation-wise voluntary CG disclosure practices for two years. During 2003, the Infosys Limited occupied the first rank in the disclosure index (35%), followed by Bajaj Hindustan Limited (30%), ITC Limited (22.5%), GTL Limited (17.5%), EID Parry (India) Limited (15%), Reliance Industries Limited (12.5%), Polaris Software Lab Limited (10%), Garden Silk Mills Limited (10%), Rajasthan Spinning Mills Limited (10%), Oudh Sugar Mills Limited (10%), Sirpur Paper Mills Limited (10%), Rolta India Limited (7.5%), Arvind Mills Limited (7.5%), S. Kumars Nationwide Limited (7.5%), Raymond Limited (7.5%). and so on. Unfortunately, there were several corporations like Pentmedia Graphics Limited, Satyam Computer Services Limited, Eskay K’N’It Limited, Bombay Dyeing and Manufacturing Limited, etc., which are having ‘zero’ score on voluntary governance index, revealing that these corporations are not following the CG practices beyond the mandatory requirements.Similarly, in 2004-05, again maximum disclosure was made by the Infosys Limited (45%), followed by Bajaj Hindustan Limited (30%), ITC Limited (20%), EID Parry (India) Limited (17.5%), Polaris Software Lab Limited (15%), Garden Silk Mills Limited (12.5%),

|

|

|

|

9. Summary and Conclusions

- CG is the set of processes, customs, policies, laws and institutions affecting the way a Corporation is directed, administered or controlled. The CG structure specifies the distribution of rights and responsibilities among different participants in the Corporation, such as the Board, managers, shareholders and other stakeholders, and spells out the rules and procedures for making decisions on corporate affairs. By doing this, it also provides the structure through which the Corporation objectives are set and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance. As a matter of principle, all the relevant information should be made available to the users in a cost-effective and timely way[15]. The CG framework should promote transparent and efficient markets, be consistent with the rule of law, and clearly articulate the division of responsibilities among different supervisory, regulatory and enforcement authorities[16]. However, Clause 49 of the Listing Agreement in India requires all “listed” Corporations to file every quarter a “CG Report,” along with other mandatory and non-mandatory requirements of disclosures. Timely disclosure of consistent, comparable, relevant and reliable information on corporate financial performance, therefore, is at the core of good CG.In fact, India has the largest number of ‘listed’ corporations in the world, and the efficiency and well-being of the ‘financial’ markets is critical for the economy in particular, and the society as a whole. It is imperative to design and implement a dynamic mechanism of CG, which protects the interests of relevant stakeholders’ without hindering the growth of enterprises[31]. Communication via corporate disclosure is self-evidently a very important aspect of CG in the sense that meaningful and adequate disclosure enhances “good” CG. Therefore, published annual reports of corporations are widely used as a medium for communicating (both quantitative and qualitative) information to shareholders, potential shareholders (investors), and other users. Although publication of an annual report is a statutory requirement, corporations normally voluntarily disclose information in excess of the mandatory requirements. Similarly, FASB Steering Committee Report[12] concluded as: “Many leading corporations are voluntarily disclosing an extensive amount of business information that appears to be useful in communicating information to investors. The importance of voluntary disclosures is expected to increase in the future because of the fast pace of change in the business environment.” Thus, corporate management, across the globe, widely recognizes that there are economic benefits to be gained from a well-managed reporting policy.In India, the Confederation of the Indian Industry took up an initiative on Corporate Governance in 1997-98. Subsequently, this was followed by a Committee set up in this regard by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). Based on the Committee’s recommendation, the Listing Agreement of all the Stock Exchanges in the country was amended by insertion of Clause 49 which specified the standards that listed Indian corporations would have to meet as well as their disclosure requirements for effective Corporate Governance. A sample of 50 listed corporations has been taken for the purpose of the present study for a period of two years, i.e., 2003-04 and 2004-05. In order to study the voluntary CG practices of the select corporations, the CG section of the annual report has been analysed. The data with respect to CG practices of the corporations have been collected from the annual reports of the corporations, as well as, Prowess database. In order to notice any disparity across industry-sectors, the sample has been selected from four industries, viz., software, textiles, sugar and paper. Appropriate statistical tools and techniques have been applied for the analysis. It has been observed that the corporations are unfortunately following less than 50% of the items of voluntary CG disclosure index. Moreover, there is no significant difference among the disclosure scores of corporations across four industries viz., software, textiles, sugar and paper.It is concluded from the foregoing analysis that even though there is a slight improvement in the voluntary CG disclosure score of the 50 corporations, yet it is considered to be a poor disclosure. Furthermore, the degree of disclosure score and number of items disclosed varies from corporation to corporation and across industries. Broadly speaking, corporations are following less than 50% of the items of voluntary CG index taken for the study. There are a few items, such as, risk management, whistle-blowing policy and code of conduct for directors and senior management personnel, which have become the part of the revised clause 49 of the Listing Agreement effective from 2005-06. Undoubtedly, there is an urgent need to extend the scope of existing mandatory clause further by covering the items from voluntary index, so that the Indian CG standards could be at par with the international level. The limitations of the study, however, are: the sample-size is limited to four industries and 50 corporations only; and the period of the study is limited up to two years only. Other researchers may find different inferences by extending the time period beyond two years. As per OECD guidelines[33], “The enterprise should disclose awards or accolades for its good CG practices, especially where such awards or recognition come from major rating agencies, stock exchanges or other significant financial institutions, reporting would prove useful since it provides independent evidence of the state of a corporation’s CG.” Infosys Limited, incorporated in 1981, was the first Indian corporation to emphasize strong CG practices in India. The corporation extended its CG practices significantly beyond what was required by the letter of the law. It voluntarily complied with the US GAAP accounting requirements, and was the first corporation to prepare financial statements in compliance with the GAAP requirements of eight countries. Moreover, Infosys set a precedent in releasing quarterly financial statements before this was the norm or the requirement. The corporation was also among the first in the country to voluntarily incorporate a number of innovative disclosures in its financial reporting, including human resources valuation, brand valuation, value-added statement and EVA report. Infosys emphasizes its commitment to a strong value system and CG practices, by making this an integral part of the training of every employee. Infosys was a pioneer in inducting independent directors to its Board, thus greatly strengthening Board oversight of senior management in the corporation. Infosys believes that good CG must also translate into being a responsible corporate citizen. Over the last 25 years, Infosys has remained committed to being ethical, sincere and open in its dealings with all its stakeholders. Infosys focus on CG not only brought global visibility to the corporation, but also created pressure on other Indian firms to raise their governance standards. This led to an encouraging trend of companies across industries scaling up their CG standards and going beyond mandatory requirements.

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML