-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2013; 2(3): 164-173

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20130203.04

Accountability: A Synthesis

Essien E. Akpanuko, Ikenna E. Asogwa

Department of Accounting, University of Uyo, Uyo, P. M. B. 1017, Uyo, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Essien E. Akpanuko, Department of Accounting, University of Uyo, Uyo, P. M. B. 1017, Uyo, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Much of the academic literature on accountability is rather disconnected. This has been a strong impediment for systematic comparison and scholarly analysis. Also, it has encouraged the proliferation of accountability solutions that are problematic than the paradox and crises the term generates. This paper aims to provide a common framework for identifying key sources of agreements and disagreement and a synthesis of thoughts on what has been learnt on the subject. The thesis and anti-thesis are highlighted and a common framework and model of understanding accountability relationships and forms developed. This was achieved by delineating the contentious issues of accountability. The review concludes that the two main views of accountability (as a mechanism and as a virtue) are not mutually exclusive. However, it is easier to enhance accountability by addressing the challenges of mechanism than the challenges of virtue. Therefore methods aimed at strengthening accountability should integrate virtues into mechanism and not vice versa.

Keywords: Accountability, Principal, Agents, Governance Answerability, Enforcement

Cite this paper: Essien E. Akpanuko, Ikenna E. Asogwa, Accountability: A Synthesis, International Journal of Finance and Accounting, Vol. 2 No. 3, 2013, pp. 164-173. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20130203.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The idea of accountability has been increasingly visible in the development field in recent years and emphasized by all actors concerned with improving governance. Economic and social development is increasingly being driven by Financial Control and Accountability in all forms and shapes. This unity of purpose and function notwithstanding, the term accountability means different things to different people depending on the context and purpose for which accountability is sought. It is used interchangeably for many loosely defined political desiderata, such as good governance, transparency, equity, democracy, efficiency, responsiveness, responsibility, and integrity[1][2][3]. However, this may be well for political spinning, policy rhetoric and white papers, but it has been a strong impediment for systematic comparative, scholarly analysis[4]. Interestingly it is not contestable that improving accountability is an effective strategy for development[5].Over three decades, the quest for accountability and the nature of activism in business and public sector has changed considerably. In the 1970s and 1980s, a series of scandals, disasters and gross violations of human rights, in which global corporations and economies were implicated, shocked the consciences of northern citizens and consumers, and fuelled protest, campaigns and media attention. Specific companies (including Nestlé, Shell, Union Carbide and Exxon Mobil) or industries (chemicals, mining, agribusiness, logging and so forth) were targeted. In the 1990s, some ‘new’ issues, such as child labour and ‘sweatshops’, and new targets, such as Nike, emerged but the balance between confrontation and collaboration shifted in favour of the latter as activism migrated from the ‘barricades’ to the ‘boardrooms’[6]. As had occurred in the case of trade unions many decades earlier, activists linked to the new social movements of the 1980s appeared to be transiting from being ‘challengers’ to ‘polity members’[7]. The instruments of change took on a very different character as ‘stakeholder dialogues’, social learning, NGO service provisioning and participation in ‘epistemic communities’ associated with CSR and private regulation became the order of the day.By the turn of the millennium, however, there were signs that another approach was gaining ground, one that involved new campaigns and stewardship regulatory proposals. There was a shift in emphasis from responsibility to accountability, from voluntary initiatives to law and public policy, from codes of conduct to verification and industrial relations, as well as a resurgence of contestation[8]. The new agenda also emphasized the issue of power and the need to build coalitions and alliances that might act as countervailing forces to big business interests. By the time of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, held in Johannesburg in 2002, there were signs that this ‘accountability movement’[9] was spreading from the North and being consolidated on a global scale, as well as in several developing countries[10]. This movement has recorded less impact in the private than the public sector.Although available statistics on poor accountability in the public sector are always questionable, it suggests that a greater part of economic activities are not accounted for. In Kenya “questionable” public expenditures noted by the controller and auditor general in 1997 amounted to 7.6 percent of GDP. In Latvia a recent World Bank survey found that more than 40 percent of households and enterprises agreed that “corruption is a natural part of our lives and helps solve many problems”[11]. In Tanzania service delivery survey data suggest that bribes paid to officials in the police, courts, tax services, and land offices amounted to 62 percent of official public expenditures in these areas. In the Philippines the Commission on Audit estimates that $4 billion is diverted annually because of public sector corruption[12].However, a 2004 World Bank study of the ramifications of corruption for service delivery concludes that an improvement of one standard deviation in the International Country Risk Guide corruption index leads to a 29 percent decrease in infant mortality rates, a 52 percent increase in satisfaction among recipients of public health care, and a 30–60 percent increase in public satisfaction stemming from improved road conditions[13].Thus it is believed that accountability mechanisms induce public sector organizations to remain relevant and responsive to the needs and demands of the groups they serve. The assumption is that, for instance, a better trained personnel and more technologically advanced operating systems will automatically account for or result in better service delivery. Experience suggests otherwise. While investments in staff, procedures and systems in the public sector (the ‘supply side’) are important, private organizations tend to perform better when they are held to account by their owners, shareholders or clients (the ‘demand side’). It is the pressure exerted by these groups that creates the incentive to perform. This is most obvious in the private sector where companies have to be responsive to the needs of their customers in order to survive [62]. However, in the public sector ‘services are failing because they are falling short of their potential to perform. They are often inaccessible or prohibitively expensive; ‘even when accessible they are often dysfunctional, extremely low in technical quality and unresponsive to the needs of the diverse clientele’[14]. What accounts for these experiences, in the most part, is the lack of understanding of the mechanism of accountability. Also, structural transformations in the nature of governance - including the privatization of some state functions - have blurred the lines of accountability, making it difficult to establish which actors hold ultimate responsibility for certain types of policies or services [61]. The ongoing process of globalization has introduced a range of new power-holders - such as multinational corporations and transnational social movements - that slip through the jurisdictional cracks separating national authorities, yet whose actions have a profound impact on people’s lives. The influence exercised over economic policy in poor countries by such multilateral institutions as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization has also reduced the autonomy of many governments, making domestic democratic accountability even more elusive. There is accountability paradox and crises. In the literature there is too much divergent accountability definitions and prescriptions, which undermines accountability practices and increase accountability crises. According to[15], ‘Our crisis in accountability is in some sense perpetual. Our disagreements about accountability are therefore also in some sense perpetual’. Unfortunately, no attempt is made to provide a consistent analytical framework for accountability crisis[4]. Therefore there is need for an exposition and a review of the concept of accountability and accountability systems. This will highlight a number of distinctions crucial to understanding how the concept of accountability is evolving in response to changes in the relationships between states and citizens, between public and private sectors, and between states and global institutions.The purpose of this essay is to provide a common framework for identifying key sources of agreements and disagreement and providing a synthesis of thoughts on what on what has been learnt. To achieve these objectives, the paper discusses the concept of accountability and types and forms of accountability resulting there from, in section 2. Section 3 discusses the theoretical framework for accountability. Section 4 delineates the issues the accountability to provide a uniform operational concept and section 5 concludes with recommendations.

2. The Concept of Accountability

- The academic literature on accountability is rather incoherent, with authors’ generating specific definition, using their own concepts, conceptualisations, and framework for studying accountability[16][15]. Some of the concepts and definitions are very loose and narrow. However, a few of these definitions are fully compatible, and this complicates issue for cumulative and commensurable research[4]. According to[17][18][19][20][21] a few papers move beyond conceptual and theoretical analyses and engage in systematic, comparative empirical research, with the exception of a series of studies in the narrow field of social psychology.Central to all definitions of accountability is the idea that one person or institution is obliged to give an account of his, her, or its activities to another. Generic models of accountability refer to any kind of relationship of this sort. In the field of governance, accountability refers to relationships between public and private actors. The applicability of general models to specific cases of government-citizen relations is often open to question, not least because the norms of what is considered appropriate vary from one country to another, one sphere of government activity to another, and so forth. Norms in accountability relationships also change over time.A second general point to be borne in mind in thinking about accountability of governments to citizens is that accountability refers not to isolated relationships, or even individual institutions operating on their own, but to a system of relationships. How one institution operates can affect how others operate and not necessarily in predictable ways. On the one hand, one poorly performing institution can undermine other specialized accountability institutions. On the other hand, when one institution fails, another can sometimes step in to fill a void. Therefore, the more talk there is of the importance of voice in accountability, the less these terms seem to mean and the less relevant they appear to have for ordinary, and particularly poor, people. The discussion that follows seeks to define accountability and to illuminate some of the many usages of the term. Accountability is an amorphous concept that is difficult to define in precise terms. However, there are two main concepts of accountability[4]:ⅰ. Accountability as a virtue andⅱ. Accountability as a social relation or mechanismThis classification model is adopted as it separates the human component (virtue) of accountability from the system component (mechanism). This method allows for easy analysis of accountability issues, aids in ascertaining the sources of disagreements and assists alignments of thoughts. This has influenced the choice the studies referred in this study

2.1. Accountability as a Virtue

- In this perspective, accountability is used primarily as a normative concept, as a set of standards for the evaluation of the behaviour of public actors. As a virtue, Accountability is a desirable quality of public officials and public organizations or as a desirable state of affairs. It refers to substantive norms for the behaviour of actors. Often, in this type of discourse, the adjective ‘accountable’ is used, as in: ‘the public officials should be accountable’, ‘accountable governance’, or ‘government has to behave in an accountable manner’. In these usages of the concept, accountability or, more precisely, ‘being accountable’, is seen as a virtue, as a positive feature of organisations or officials. Accountability in this very broad sense is used to positively qualify a state of affairs or the performance of an actor. It comes close to ‘responsiveness’ and ‘a sense of responsibility’, a willingness to act in a transparent, fair, and equitable way[22]. Accountability in this sense of virtuous behaviour is easily used, but very hard to define substantively. Accountability in this sense is an essentially contestable concept[23]. This is so because there is no general agreement about the standards for such behaviour, and even if there were, such standards differ, depending on role, institutional context, era, and political perspective[24]. Aware of multiplicity of the usage of the concept,[25] distinguishes no less than five different dimensions of accountability: transparency, liability, controllability, responsibility, and responsiveness. These are ideographs and umbrella concepts which need extensive operationalization and often cannot be measured along the same scale. The difficulty, if not impossibility, of defining or standardizing accountability as a virtue becomes very clear. However, Global Accountability Framework provides standards (norms of good corporate governance in the global arena) for accountable behaviour of transnational actors[26]. They should connect with stakeholders, be responsive to their needs and views and provide explanations, they should be open, engage in dialogue, and be willing to learn from it. To ensure the working of these standards, four core dimensions are identified: transparency, participation, evaluation, and complaint and response mechanisms. Each of these four dimensions is formulated as a standard for accountable behaviour[27]. Although developed for transnational actors, the standards can be adapted to fit specific national, local, political and institutional variations.

2.2. Accountability as a Social Relation or Mechanism

- Accountability is seen as an institutional relation or arrangement in which an actor can be held to account by a forum. Here the locus of accountability studies is the way in which these institutional arrangements operate and broadly, accountability exists when there is a relationship where an individual or body, and the performance of tasks or functions by that individual or body, are subject to another’s oversight, direction or request that they provide information or justification for their actions. Accountability describes a relationship in which A is accountable to B if A is obliged to explain and justify his or her actions to B or if A may suffer sanctions if his or her conduct, or explanation for it, is found wanting by B[28]. Accountability is thus a relationship of power and it denotes a specific variety of power: the capacity to demand that someone justify his or her behavior and the capacity to impose a penalty for poor performance. In governance, it means answerability for one's action and behaviour[29]. In simple terms accountability is the right to be questioned and the answerability for one’s action and behavior, defined by the relationship of responsibility, obligation and duty as equity demands. Without the right to question, by interference, there would never be accountability, no matter the number of times one cares to mention or sing it. Intuitively therefore, there is accountability if, and only if, the public officers anticipate questions within and after their stewardship to the society[30]. Contrary to the view of some studies, the relationship between the steward and the public, the actual account giving, usually consists of at least three elements or stages[4]:Obligation of the steward to inform the principal about his or her conduct. This can be done by providing various sorts of data about the performance of tasks, about outcomes, or about procedures. Often, particularly in the case of failures or incidents, this also involves the provision of explanations and justifications. The possibility for the principal to interrogate the steward and to question the adequacy of the information or the legitimacy of the conduct. This explains the observed interchangeable used of ‘accountability’ and ‘answerability’ in literature. Reward or consequences enforcement. The principal may pass judgement on the conduct of the steward. It may approve of an annual account, denounce a policy, or publicly condemn the behaviour of an official or an agency. In passing a negative judgement, the principal or her agencies frequently imposes sanctions of some kind on the steward. Enforcement suggests that the public or the institution responsible for accountability can sanction the offending party or remedy the contravening behavior[1][31]. Therefore, accountability as a mechanism exist where there is an obligation of the government, its agencies, public officials and persons in stewardship positions to provide information about their decisions and actions and to justify them to the public, owners and those institutions of accountability tasked with providing oversight, and the enforcement of reward or consequences to remedy contravening behavior. As such, different institutions of accountability might be responsible for each or all of these stages. This has given rise to different types and forms of accountability.

2.3. Types of Accountability

- Accountability as a mechanism types and forms are broadly categorized using two basis:a. Accountability relations and b. Hierarchy or nature of obligation In the first category we identify the following types: ⅰ. Political and social accountabilityⅱ. Economic accountability and ⅲ. Financial accountabilityPolitical and social accountability, according to the Royal Commission on Accountability (RCA) is ‘the fundamental prerequisite for preventing the abuse of delegated power, for ensuring instead that power is directed towards the achievement of broadly accepted national and social goals with the greatest possible degree of efficiency, effectiveness, probity and prudence’[29]. Otherwise known as Democratic accountability, socio-political accountability is concerned with the ability of the governed to exercise control over office holders to whom power has been delegated. Achieving the consent of ordinary people is a difficult enough task on its own, and it is complicated by other factors. Socio-political accountability implies an orientation towards a top, demanding that functionaries are accountable to it. Looking at accountability from a wider perspective,[32] observe various ‘institutional practices of account giving’. Thus, in defining ‘socio-political accountability’, they make a distinction between different types of potential accountability relationships and related sets of norms and expectations: organizational accountability, professional accountability, political accountability, legal accountability and administrative accountability (see also[22]). Adopting their definition, we see accountability as ‘a social relationship in which an actor feels an obligation to explain and to justify his conduct to some significant other’[22]. Economic Accountability is concerned with determining the validity and appropriateness of goals, the factors and conditions that have facilitated or retarded progress and ways of effecting improvements[33]. Financial accountability is normally associated with stewardship accounting (financial accounting). It is the rendering of accounts for the affairs of an organization or enterprise to the owners of the resources of the organization or enterprises by a steward[34].In the second category we identified the following forms[35][36]:ⅰ. Vertical Form ⅱ. Horizontal Form andⅲ. Diagonal Form of AccountabilityVertical channels of accountability are those that link citizens (principals) directly to government (agents). Vertical accountability occurs when the state is held to account by Non state actors. Elections are the formal channel of vertical accountability, but this camp also includes informal processes through which citizens organize themselves into associations capable of lobbying governments, demanding explanations, and threatening less formal sanctions, such as negative publicity.Horizontal channels of accountability involve public institutions responsible for keeping watch on government agencies. Horizontal institutions of accountability - ombuds people, auditors’ general, anticorruption bureaus, etc - are meant to complement the role played by electoral institutions. Horizontal accountability exists when one state actor has the authority - formal or informal - to demand explanations or impose penalties on another. Executive agencies must explain their decisions to legislatures; in some cases they can be overruled or sanctioned for procedural violations. Political leaders hold civil servants to account, reviewing the bureaucracy’s execution of policy decisions. The many innovations recommended for improving the accountability of states to citizens involve breaking down the barriers separating vertical and horizontal channels of accountability has given rise to a new structure of authority. Getting citizens involved directly in horizontal (state-to-state) processes of accountability is a new form of accountability. This approach is referred to as diagonal accountability. It is believed that this diagonal structure (participation of ordinary people in the government’s financial auditing functions) could help government auditors do a better job. The reason being that citizens could augment the capacity of thinly stretched government auditing departments and exercise oversight over the way in which these agencies go about their business and root-out collusion between official watchdogs and the executive departments they audit. Objections to such approaches to “hybrid accountability” range from self-interest on the part of corrupt audit agencies (who do not want their mis-deeds exposed to scrutiny by ordinary citizens) to legitimate worries that audit agencies could have their independence undermined if, in the name of citizen engagement within oversight bodies, people with hidden agendas find themselves able to disrupt the work of auditors’ general, ombuds people, and other government officials.

3. The Theories of Accountability

- The question of who should be accountable, to whom and why is answered in this section. The theories provide a basis for an understanding of these questions. The theories of accountability have developed out of the thoughts and ideas of the stewards-responsibility-stakeholder relationship that defines it. These ideas can be broadly grouped into three theoretical categories[37][38] from the oldest to the latest: (a) Principal-Agent models, (b) New Public Management perspectives, and (c) Neo-Institutional Economics frameworks.

3.1. Principal-Agent Models

- Of the three theories of stakeholder’s relationships in a State, the most widely used is the principal-agent model. In this model the state is led and managed by a benevolent dictator (the principal). The main aim of the principal is to motivate other government officials (agents); this includes the citizens (stakeholders), to act with integrity in the use of public resources[39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]. This model believes in the “crime and punishment” theory of[40], which opines that public officials are held accountable when the costs (punishment) associated with the crime of non-accountability and other corrupt acts exceeds the gains.Thus, given the crime-punishment relationship, the principal can ensure accountability by reducing the number of transactions over which public officials have discretion. This reduction in the scope of gains (transactions with discretion) increases the possibility for restraining or increasing the punishment for corruption. Based on the increased possibility of restrain in the principal-agent relationship in the State, accountability (A) equals monopoly (M) plus discretion (D) minus corruption (C) {A = M + D – C}[43]There are two variations of this theory; the state without and with the legislators. In the state without legislators’ variation, accountability can be ensured by rules-driven government that includes strong internal controls with little or no room for discretion by public officials (agents). This variation of the principal-agent model gained wide acceptance in public policy circles and served as a foundation for empirical research and policy design to combat administrative, bureaucratic, and petty corruption. However, the appropriateness of this approach in highly corrupt countries - where the rules enforcers themselves add an extra burden to corruption and lack of discretion is thwarted by collusive behavior by corruptors - has been challenged. Lack of discretion is often cited as a defense by corrupt officials who partake in corruption as part of a vertically well-knit network enjoying immunity from prosecution[46].The second variation of this model integrates the role of legislators and elected officials into the analysis of corruption. The legislators and elected official are representatives if the citizens. Their role is to check the excesses of the principal on behalf of the citizens and enhance the accountability relationship. However in highly corrupt countries, policy and legislation are manipulatively instituted in favor of particular interest groups (representing private sector interests and entities or individual units of public bureaucracy competing for higher budgets) in exchange for rents or side payments (in Nigeria this rents or side payments are popularly called ‘Ghana must go’). Legislators weigh the benefits of being non-accountable (the personal monetary gains from corrupt practices and improved chances of re-election) against the costs (the chance of being caught, punished, and losing an election with a tarnished reputation) to make a decision.The decision to compromise accountability and abate corruption has a number of factors. This includes: (a) campaign financing mechanisms, (b) information access by voters, (c) the ability of citizens to vote out corrupt legislators, (d) the degree of political contestability, (e) the type of electoral system, (f) the democratic institutions and traditions in place, and (g) the institutions of accountability in governance[47][48][49][50][45][51]. This model applies also in the private sector. Where the managers are the principal, the employees are the agents and the owners and the communities in which the businesses exist in are the stakeholders. The two variations also exist; without and with the board of directors. This theoretical framework is useful in analyzing political, social, economic and financial accountability.

3.2. New Public Management (NPM) Frameworks

- The NPM calls for fundamental civil service and political reforms to create a government that is under contract and accountable for results to the principal, the leader or manager of the State. The contractors are the public officials. The citizen’s mandate is in the hands of the principal. Under these reforms, public officials would no longer have permanent rotating appointments but instead would keep their jobs as long as they fulfilled their contractual obligations[52][53]. According to[13] the New Public Management (NPM) literature reveals a more fundamental discordance among the public sector mandate, its authorizing environment, and the operational culture and capacity. This discordance contributes to government acting like a runaway train and government officials indulging in rent-seeking behaviors, with little opportunity for citizens to constrain government behavior. However, it is argued that such a contractual framework may encourage competitive service delivery through outsourcing, strengthening the role of local government as a purchaser but not necessarily a provider of local services. Where the citizens are empowered to demand accountability for results, opportunities for corruption is reduced and citizen-centered governance is produced. Thus,[52] noted that citizen empowerment holds the key to enhanced accountability. On the contrary,[52][51][55] disagree with such conclusions and argue that NPM could lead to higher corruption rather than greater accountability, because the tendering for service delivery and separation of purchasers from providers may lead to increased anti-accountability behaviors and enhanced possibilities for corruption. This is the case in some states in Nigeria where consultants are used in the collection of government rents, rates and taxes.

3.3. Neo-Institutional Economics (NIE) Frameworks

- The Neo-institutional economics frame presents a refreshing perspective on the sophistication of the causes and limited cures of corruption. This theory is a principal-agent relationship, where the agent is more advantaged than the principal. The leader, public officials and managers are the agents while the citizens and shareholders are the incapacitated principals. The principals’ effectiveness in ensuring accountability is determined by the agent. This model argues that corruption results from the opportunistic behavior of public officials and managers (agents), as citizens and shareholders (principals) are either not empowered to hold agents accountable for their corrupt acts or face high transaction costs in doing so. The capacity of the Principal to act or deicide is limited to available or incomplete information provided by the agent. They face high transaction costs in acquiring and processing more information. In contrast, agents are better informed[13]. This asymmetry of information allows agents to indulge in opportunistic behavior that goes unchecked because of the high transaction costs faced by principals and the lack of adequate countervailing institutions to enforce accountability in governance. These institutions, the internal control systems and other means (external audits) of checking the excesses of the agents are under the control of the agents. The NIE theorist asserts that when the institutions, incentives and sanctions are gotten right, service providers use resources well, deliver required service and level of performance, and provide for those in need. A contrary opinion is expressed by[56]. They argue that the above assertion is impossible in a centrally planned economy as bureaucrats have incentive to produce less service, cause shortages and collect bribes for under-produced services. Therefore, accountability can be ensured through economic liberalization, political democratization and social modernization[59]

4. Delineating the Issues in Accountability

- The various issues raised in discussions of accountability can be captured in two broad areas[57]:a. The Answerability and Enforcement Aspects of Accountabilityb. The Principal-Agent Conception of Accountability: who is answerable to whom and why?If we agree on who is answerable to whom and why, it is logical that the solution to who enforces what can be found. It may also provide an understanding for the development of an approach to reduce corruption and enhance accountability.

4.1. The Principal-Agent Conception of Accountability

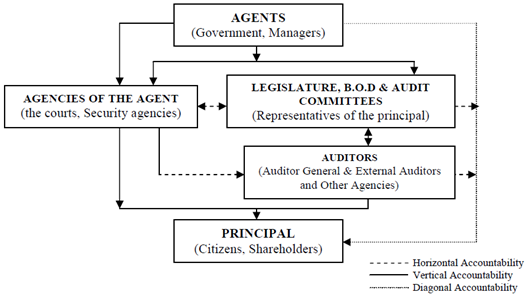

- Following from the theories, the idea of accountability is most often rendered in terms of principals and agents. Principals delegate authority to agents, who are expected to act on the principals’ behalf. In democracies the citizens (or voters) are the principals, and government officials (politicians and civil servants) are the agents. In business enterprises, the shareholders’ are the principal and the managers are the agents’. In both cases the agents’ and the principal can have representatives (agents). The central problem of principal-agent theory is ensuring that agents (or agents/ representatives to the agents’) do what principals (or agents to the principal) have empowered them to do, which is to promote the principals’ welfare. Agents have a tendency to promote their own interests instead, often in collusion with a specific institutions or bodies of the principal (agents to the principals). Holding unto the deduced definition of accountability (as a social mechanism) as social relationships in which principals have the right and ability to demand answers from agents, questions their proposed or past behavior, discern that behavior, and to decide and enforce sanctions on agents in the event that the behavior is unsatisfactory; this translates into;a. A requirement that governments (her agencies and agents to the agencies) account for their actions to citizen (or their representatives and other agents to the citizens) and face the consequences or sanctions at the ballot box if deemed to have failed in their public duty. Thus, an elected politician is the agent for the electorate, who are the collective principal. b. Similarly, a requirement that managers’ {the agent or agents to the agent and the agents (External auditors’) and representatives of the principal (Board of Directors and audit committees)} account for their actions to owners’ (shareholders’) of a business enterprise and face the consequences or sanctions at the annual general meeting if deemed to have failed in their duty. The accountability relationship can be represented in the figure 1.A common case where accountability is compromised is where the principals interests are subverted by manager or government {the agent or agents to the agent by collusion with the agents (External auditors’) and representatives of the principal (Board of Directors, audit committees and legislators as the case maybe)}. This subversion of accountability is not a mechanism problem but a virtue problem. This virtue question bothers on the very nature of man and the tendency to be corrupt. Improving accountability as a virtue has led to the development, by concern persons and stakeholders, of complicated and sometimes, systems that are impossible to operationalise.

| Figure 1. The principal Agent Accountability relationship |

4.2. The Answerability and Enforcement Aspects of Accountability

- The two major aspects of the accountability relationships that is pivotal to analyzing accountability institutions or proposing reforms to them are answerability and enforcement[59]. The issue here is that what is right or wrong will be seen from two perspectives; the principal’s perspective and the agent’s perspective. Firstly, answerability means having to provide information about one’s actions and justifications for their correctness. Thus answerability consists of two aspects; explanatory and informational components, the relevance of which varies from one circumstance to another. The less demanding form of answerability requires a holder of delegated power simply to furnish an explanation, or rationale, for his or her actions. This should provide the substantive value for principals who seek full, evidence-based justification of how competing considerations were weighed and justifiable decisions reached. Accountability is ensured, even when sanctions are not imposed, when the explanatory component to answerability is combined with the information component (an obligation of full disclosure that requires the official to reveal the evidential basis upon which decisions were taken, such as supporting documentation and testimony from citizens consulted). In such circumstances it is difficult for the agents to subvert accountability with explanations based on unsound logic. At this point there will be an agreement between the two parties as to what was rightly or wrongly done.Secondly, enforcement means having to bear the consequences imposed by those dissatisfied either with the actions themselves or with the rationale invoked to justify them. Enforcement like answerability also has two distinguishable components that must be integrated into the nature of accountability relationships. The first component is the adjudication of the nature of the power-holder’s performance. This involves determining the persuasiveness of his or her explanation in light of available information and prevailing standards of public conduct. The second component is sanctioning. After a verdict on the viability of the agent’s explanation, the enforcing agency must decide on the nature of the penalty to be applied. This process involves three components[36]: a. Assessing the future deterrent effect of competing sanctions b. Considering whether the public will believe that justice has been done, andc. The capacity of the sanctioning authority to carry out the enforcementThis unbundling of the main concepts is particularly important for analyzing the role of political institutions in promoting accountability, because political institutions often have quite specific mandates for particular circumstances. A representative body (a legislature or board of directors) may be able to demand information but find it difficult to rule authoritatively on the explanation for an executive agency’s decisions. The body may be able to withhold future funding, but determining legal compliance (whether the agency in question conformed to the obligations stipulated in law) is usually the province of the courts[35]. This confirms earlier observation that some of the institutions of accountability can perform more than one function. For instance the courts as horizontal institution of accountability are to ensure that governments comply with legal norms - not least their obligation to hold free and fair elections - and to adjudicate on conflicts between the legislative and executive branches of government. On the other hand, the courts also provide a forum which citizens (principals engaged in a relationship of vertical accountability with government agents) and ensure that officials do not trespass on their democratic rights.

5. Conclusions

- From the review, the two concepts of accountability (as a virtue and as a mechanism) are very useful for the study of, and the debate about governance. The problem in set when they are clearly distinguished, as they address different sort of issues and imply very different sort of standards and analytical dimensions. Studies that, often implicitly, use accountability in the active sense of virtue, focus on the actual performance of officials and agents. These are basically studies about good public or corporate governance. Studies into accountability as a mechanism, on the other hand, focus on the relationship between agents and principals. They ascertain whether there are any relations, and if such can be called accountability mechanisms, how these mechanisms function, and what their effects are in terms of control. However, the two concepts are closely related and not mutually reinforcing. Thus, accountability mechanisms can be important sources of norms for accountability as a virtue. Notions of accountability as virtues are produced, internalised, and, where necessary, adjusted through the mechanism[58][60] and not the reverse. There is no accountability without accountability arrangements. Accountability mechanisms keep public actors on the virtuous path and prevent them from seeking selfish interest.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML