-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2013; 2(2): 75-81

doi:10.5923/j.ijfa.20130202.04

The Effect of Ownership Structure on Firm Performance in Malaysia

Kamarun Nisham Taufil-Mohd , Rohani Md-Rus , Sami R. M. Musallam

College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Kedah, 06010, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Rohani Md-Rus , College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Kedah, 06010, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper aims to investigate and analyze the effect of ownership by different groups of investors on the performance of listed companies in Malaysia for a period of ten years from 2000 to 2009. The results of GLS show that firm performance is positive and significantly related to five government-linked investment companies, foreign ownership, and DPIIs ownership while it is negatively and significantly related to state ownership. These results imply that government ownership through GLICs does not lead to value destruction. In fact, it could lead to better monitoring. However, state ownership leads to lower values.

Keywords: Glics Ownership, State Ownership, Institutional Ownership, Corporate Governance, Performance

Cite this paper: Kamarun Nisham Taufil-Mohd , Rohani Md-Rus , Sami R. M. Musallam , The Effect of Ownership Structure on Firm Performance in Malaysia, International Journal of Finance and Accounting, Vol. 2 No. 2, 2013, pp. 75-81. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20130202.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Studies on ownership structure and performance have looked at many types of ownership; however, the study on the ownership by government linked companies is still lacking. The study on this type of ownership is important as it may provide recommendations for policy makers. Furthermore, ownership structure is significant in determining firms' objectives, maximizing shareholders wealth, and disciplining of manager[1]. The ownership structure can be grouped into either a widely held firm or a firm with controlling shareholders or concentrated ownership. The concentrated ownership is higher in Asian countries than in the United States (US) and United Kingdom (UK)[2]. Concentrated ownership in Malaysia takes the form of 67.2 percent of companies are owned by families, 13.4 percent are owned by the government, and 10.3 percent are widely held by financial institutions[3]. As government owned substantial stake in private firms, it is important to examine the performance of government held companies.Government holdings could be both at the federal or state level. At the federal level government ownerships is measured through the holdings of government linked investment companies (GLICs). There are two types of GLICs. One is GLICs funded by private investors such as Employee Provident Fund (EPF), Armed Forces Fund (Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera or LTAT), Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB) and Pilgrim Fund (Lembaga Tabung Haji or LTH). The other is government funded GLICs such as Khazanah Nasional Berhad (KNB), Kumpulan Wang Amanah Pencen (KWAP) and Ministry of Finance Inc (MFI). GLICs play an important role in the development of Malaysia's economy. Government monitors the performance of GLICs as poor performance of GLICs would have backlash on the government. Thus government would appoint competent officers on these GLICs, have these individuals report to the relevant government agencies, provide funds to the government funded GLICs, and implicitly guaranteeing unit holders investments. Realizing the importance of GLICs in the domestic capital market, government introduces several measures. As an example, on 29th of March, 2010, while presenting the New Economic Model (NEM), Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Tun Razak indicated that some GLICs should divest off their investments in Malaysia. Furthermore, the government would allow EPF to invest 10% of its assets overseas to diversify its portfolio. This would create more room domestically for new participants. Prime Minister stressed the same point in his budget speech on 15th of October, 2010 where he reiterated that GLICs should divest their shareholdings in companies listed on Bursa Malaysia to increase liquidity and trading velocity in the market. GLICs will also increase their investments in oversea markets to explore opportunities for better performance. Thus it is important to measure the performance of GLICs in Malaysia to determine if the participation leads to better firm performance.Another important class of shareholders is state or province and it is monitored by the respective state government. State ownership has different objectives than private ownership. In Malaysia, according to government policy, state ownership represents an important socio-political agenda in order to rationalize the distribution of economic resources among different races. State controlled companies may pursue objectives that are different from shareholders wealth maximization. Another major group of investors are non-government-linked domestic and foreign institutional investors. These are professional investors who should lead to better performance. Majority of the firms around the world are controlled by their founders, families and heirs. In Western Europe, South and East Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa, the vast majority of publicly listed firms are family controlled[4]. In Malaysia, many listed firms are owned and controlled by family and that firms appear to be inherited by the founder’s descendants[5]. In fact, Malaysia has the third highest concentration of control being dominated by family founders and their descendants after Thailand and Indonesia[6]. High concentration of ownership could reduce agency problem between shareholders and managers as shareholders would monitor managers. However, in a concentrated ownership environment such as in Malaysia, managers are appointed among the family members. Thus, the problem is between majority shareholders who serve as managers and minority shareholders. It is important therefore to look at the effect of family ownership on performance. This paper aims to investigate and analyze the effect of ownership by different groups of investors on the performance of listed companies in Malaysia for a period of ten years from 2000 to 2009. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section presents literature review and hypotheses. This is followed by research methodology. Subsequent section reports empirical results. Conclusions, contributions, and suggestions for future research are provided in the final section.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

- There is major difference between GLICs ownership and state ownership. GLICs are monitored by federal government. However, federal government does not interfere with the operation of GLICs. Private sector funded GLICs performance is monitored by unit holders. If the return provided by private sector funded GLICs are low, unit holders would question the competency of GLICs managers. Thus, private funded GLICS have an incentive to increase the performance. One way of doing this is through monitoring companies that are held by GLICs.As for government funded GLICs, especially KNB and MFI, they have different objectives. These two GLICs would invest in companies that have a national strategic interest such as Tenaga Nasional Berhad (electric utility company) and Malaysia Airline System (national airline carrier). Government funded GLICs would monitor these companies; however since these companies might operate in unattractive industries, the performance of these companies might be poor which would reflect on the performance of the GLICs. KWAP, another government funded funds, might perform better compared to KNB or MFI since they managed funds that would pay pension to retired government employees. So, in this case they have to identify and monitor companies with expected better future performance. In Malaysia the effect of the percentage of total equity of government ownership is positive and significant on firm performance, indicating, government can monitor the company activities, and align them toward attaining higher company performance ([7],[8]). In addition, other studies find that the effect of government ownership, as measured by using dummy variable, is also positive and significant on firm performance[9]. In this study we try to separate government ownership along various types of GLICs because we expect that different type of GLICs would have different impact on performance. We expect that privately funded GLICs and KWAP would affect performance positively while the effect of KNB and MFI are difficult to determine. State ownership is different than federal government ownership as state ownership refers to companies held by state. The study on state ownership and performance is limited in Malaysia. State ownership includes but it is not limited to Permodalan Negeri Selangor Berhad, Yayasan Islam Terengganu, and state economic development corporations. State-owned companies are subject to political intervention and subsidizations to achieve state objectives. Reference[10] argue that state-owned companies do not focus on maximizing firm performance because state has political as well as economic objectives, and that corporate performance in firms will be inferior because of weaker governance arrangements. The costs of agency increased in state-owned companies because of conflicting objectives between pure profit goals of commercial businesses and goals related to the interests of the state. Therefore we hypothesize that state ownership would have negative influence on performance.Blockholders, in the form of foreigners and domestic private institutional investors (DPIIs), could play an effective monitoring role. Given that many firms in Malaysia are controlled by families, the existence of blockholders could reduce the agency problems between majority and minority shareholders. By controlling a significant amount of ownership, blockholders have an incentive to monitor the firm performance as their wealth is tied up to the firm performance. Furthermore, institutional investors, looking for profitable investment opportunities would only invest in firms with expected better future performance. Foreign investors allow firms to easily access superior technical, managerial talents, and financial resources[11]. However, there are two reasons in where foreign ownership affects firm performance negatively[12]. Firstly, foreign shareholders face difficulties to monitor managers because the company is located in another country. Secondly, most of the firms that have foreign corporations as their controlling shareholders are run by professional managers who do not hold any stake in the firms. Meanwhile, some studies find that the effect of foreign ownership is positive and significant on firm performance[13]. Their results indicate that foreign investors monitor managerial behaviours and thus maximize firm value. In Malaysia, references ([8],[9]) find that foreign ownership influences performance positively. Reference[7] looks at 15 companies over a six-year period where Khazanah Malaysia own at least 20 percent and find that performance is not related to foreign ownership. In this study, we expect foreign ownership would affect performance positively.DPIIs are made up of unit trust, insurance companies and other financial institutions. Investments made by DPIIs in Malaysia are not as large as the investments of GLICs. Thus, even though DPIIs might play a monitoring role but their monitoring incentive is not as high as GLICs. However, given that DPIIs are managed by professionals who are constantly looking for attractive investment opportunities, we hypothesize that DPIIs would only invest in better performing companies. Family ownership has greater effects on firm performance because the firm is a reflection of family legacy. Besides that the firm performance would affect families’ reputation and standing in the society. Reference[14] argues that as family welfare is closely linked to firm performance, families may have strong incentive to avoid corporate diversification because of substantial negative effects on shareholders’ value. The effect of family ownership on performance is not clear. Many reasons cause a positive relationship between family ownership and firm performance. Among them are better monitoring system which leads to lower agency problems[15], superior information and better knowledge of their business[16]. Meanwhile, negative relationship might also be observed because family ownership might lead to unclear or even undefined roles and responsibilities between family shareholders and family managers[16] and might seek to extract private benefits from the firm[17]. Families might also take actions that benefit their members at the expense of firm performance because of substantial control rights, and might lead to wealth expropriation in the presence of less than transparent financial markets.Reference[18] finds that performance is positively and significantly related to family ownership. As higher proportion of the wealth is invested in firms, families have greater incentives to monitor performance of managers and if they are the managers, they do not expropriate wealth from minority shareholders. However, reference[19] finds that performance is negatively and significantly related to family ownership. This result indicates that higher family ownership leads to weaker governance. On the other hand, reference[20] finds that performance is not related to family ownership. In this study, we hypothesized that family ownership does not affect firm performance.Higher board ownership improves firm performance because it better aligns the incentives of managers with other shareholders, thereby reducing agency problems between managers and owners. Reference[21] argues that ownership by managers and board members provides an incentive to ensure that the firm is managed properly as their wealth are being tied up to the firms performance. Executives are concerned about the firm performance as their pay and future career opportunities depend on it. Thus, based on agency theory larger board ownership leads to better performance. Findings on the effect of board ownership on firm performance are mixed. Performance is positively related to board ownership which supports the agency theory arguments, as in[22]. However, reference[23] finds that performance is negatively and significantly related to board ownership, indicating that higher shareholdings by directors allow them to entrench themselves and taking on projects that serve their interest. Therefore, in this study we hypothesized that firm performance is not related to board ownership.In order to identify the specific effect of ownership variables on firm performance, this study controls for the effect of firm age, firm size, and leverage ratio, which might affect performance. However, the effects of these three variables are not clear[13].

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data

- There are 760 non-financial companies listed on the main board and second board of Kuala Lumpur stock exchange (KLSE) at the end of 1999. The population of 760 companies is identified from Datastream. Out of the population, 190 companies are selected randomly. Relevant variables for these 190 companies are collected from 2000 up to 2009 or up to the year before delisting. This procedure leads to the final sample of 1716 company-year observations. The years 2000 until 2009 are selected because after Asian Financial Crisis (AFC), more attention is given to corporate governance. As an example, Malaysian Code of Corporate Governance was introduced in March 2000 by Securities Commission. Market-to-book-value-ratio (MTBVR) is used as the dependent variable to measure performance. Ownership and control variables are used as the independent variables. Data on ownership is collected manually from annual reports while the rest of the data is collected from DataStream.

3.2. Techniques of Data Analysis

- This study uses panel data analysis to analyze the impact of independent variables on performance. A panel data analysis is used because it can eliminate the unobservable heterogeneity that exists in the sample. Panel data usually gives the researchers a large number of data points, increasing the degree of freedom and decreasing the collinearity among the independent variables. It may also improve the efficiency of statistical estimates. The following model is estimated:MTBVRit = B0 + B1 EPF it + B2 PNBit + B3 LTAT it + B4 LTH it + B5 KWAPit + B6 KNB it + B7 MFIit + B8 SOit + B9 FOit + B10 DPIIOit + B11 FAMOit + B12 BOit + B13 FSIZEit + B14 FAGEit + B15 LEVit +ewhere MTBVRit = Market to book value of company i in year t EPF it = EPF ownership in company i in year tPNBit = PNB ownership in company i in year tLTAT it= LTAT ownership in company i in year tLTH it= LTH ownership in company i in year tKWAPit= KWAP ownership in company i in year tKNB it = KNB ownership in company i in year tMFIit = MFI ownership in company i in year tSOit = State ownership in company i in year tFOit = Foreign ownership in company i in year tDPIIOit =DPIIs ownership in company i in year tFAMOit =Family ownership in company i in year tBOit =Board of directors ownership in company i in year tFSIZEit = The natural log of total assets of company i in year tFAGEit = The natural log of firm age since listed on Bursa Malaysia of company i in year tLEVit ==Long term debt divided by total assets of company i in year tSo far it is assumed that ownership variables explained performance. However, it could be the other way around where performance influences types of ownership. As an example one of the GLICs might invest in companies because through their research they believe that the companies are underpriced. In this case, we have a problem of endogeneity. One way to overcome this problem is to use two-stage least squares (2SLS) method. In this case, instrumental variables have to be identified. A difficulty in implementing 2SLS is to identify the relevant instrumental variable. In this study, five variables are used as instruments based on previous studies: natural log of sales, square of natural logarithm of sales that is included to allow for nonlinearities in the natural logarithm of sales, standard deviations of stock returns, cash holdings and sales growth. Hausman test is used to test for the existence of endogeneity.

4. Results and Discussions

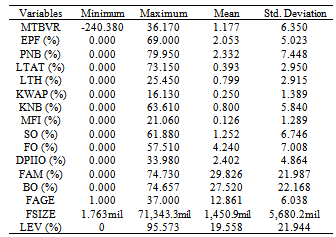

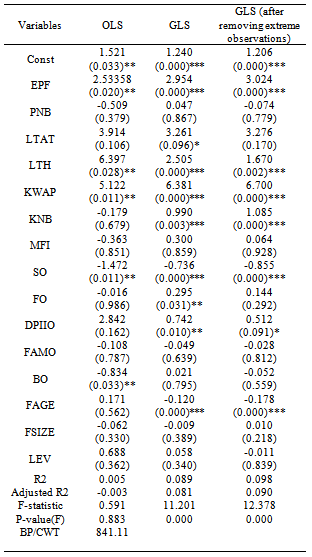

- Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study. The mean value for MTBVR is 1.177. The range of MTBVR is from a lowest value of -240.380 to highest value of 36.170. When comparing among GLIC ownerships, the highest mean value is recorded by PNB (2.332%) followed by EPF (2.053%). For the rest of GLIC’s, the average ownership is less than 1%. Among the different groups of ownerships, family records the highest average value of 29.83%. It shows that on average, companies are controlled by families. Moreover, board ownership records an average of 27.52%. It is not surprising since families who own a lot of shares might demand that their representatives serve on board of directors. This also shows that the problem between majority and minority shareholders might be observed in Malaysia. The average firm age is 12.861 with the oldest firm has been listed for 37 years, while the youngest is 1 year. The average of firm size is RM1,450,900,000 where the minimum and maximum values are RM1,763,000 and RM71,343,301,000 respectively. For leverage ratio, the average reported is 19.558%. In order to measure the degree of relationship between the independent variables, Pearson’s correlation is used. Based on the results, none of the correlation coefficients has a value higher than 0.8 or 0.9, which show that there is no problem of multicollinearity. The highest correlation is 0.625 between board ownership and family ownership which shows that family is represented on the board of directors.Table 2 shows the empirical results of OLS and GLS estimations. Results of OLS are summarized in column 2 of Table 2. Diagnostic test are performed to check if the OLS estimation suffers from the problems of heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation. Cook-Weisberg/Breusch-Pagan (CW/BP) and Durbin-Watson (DW) tests are used to measure heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation problems respectively. The null hypothesis of no heteroscedasticity and no autocorrelation could be rejected as CW/BP test gives a value of 841.11 with p-value of 0.000 and DW test gives a value of 1.14 with critical lower bound DW value of 1.903. Since OLS estimation suffers from both problem, GLS is used.Results of GLS are summarized in column 3 of Table 2. The adjusted R-squared is 8.1%. The reported F-statistic of 11.201 is statistically significant at 1 percent, which shows that all independent variables jointly are not equal to zero. Overall, MTBVR is positively and significantly related to EPF, LTAT, LTH, KWAP, and KNB. This result implies that all five GLICs ownership leads to better governance and enhances performance. It also implies that managers of the companies under government control have incentives to monitor the performance since their promotion prospects could be influenced by the performance of the company. Furthermore, EPF, LTAT and LTH managed unit holders’ funds. Unit holders expect certain return every year. Lower return would lead to dissatisfaction among them. Thus, the performance of these GLICs is monitored consistently by both government and unit holders. This put more pressures on managers of GLICs to manage the fund properly. As for KWAP, it managed pension for government retirees. The higher is the return earned by KWAP, the lower would be the government obligations to retirees.

|

|

5. Conclusions

- This paper investigate and analyze the effect of ownership by different groups of investors on the performances of Malaysian listed companies using a panel data analysis of 190 companies that are listed on Main Market of Bursa Malaysia over a ten-year period from years 2000 to 2009. This paper uses generalized least squares (GLS) method of estimation instead of the ordinary least square (OLS) to estimate the panel data regression. The results show that firm performance is positively and significantly related to ownerships of five GLICs, foreigners and DPIIs while it is negatively and significantly related to state ownership. Several contributions emerge from this study. First, to the best of knowledge of the authors, this is the first study to examine the impact of each GLIC on firm performance. Second, federal government would like to reduce GLICs’ investments in Malaysia and give more opportunities to domestic and foreign investors to invest in Malaysia with the expectation that the action could increase liquidity and trading in Bursa Malaysia. This study finds that GLICs perform well in Malaysia. Thus if they reduce their investments in Malaysia and invest abroad, it could adversely affect their returns to shareholders. Hence, this study recommends that even though GLICs could reduce the risks of their portfolios by investing abroad, they must not be hasty in venturing abroad and still focus on domestic market where they have a competitive advantage compared to overseas investments. Third, this study extends the scope in finance and accounting literature, especially in the area of corporate governance and also offers an additional perspective to the study of ownership structures in the context of an emerging economy. Future research that tries to investigate the relationship between ownership with company performance can also include other control variables to the study such as industry effects, firm risk, board characteristics, and the capital intensity to ensure the robustness of the results. Other performance measures also can be used as a proxy for firm performance such as return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), earning per share (EPS), return on sales (ROS), return on investments (ROI), profit margin (PM), and economic value added (EVA). Then, the results can be compared to this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML