-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

p-ISSN: 2168-4812 e-ISSN: 2168-4820

2012; 1(6): 198-207

doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20120106.09

Inflation Risk Management in Project Finance Investments

Roberto Moro Visconti

Department of Business Management, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy

Correspondence to: Roberto Moro Visconti , Department of Business Management, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Project finance investments are a key backbone for a wide range of sustainable and bankable new infrastructures; being long term investments, they are highly exposed to inflation risk, which in Public Private Partnerships is mostly borne by the private counterpart and its backing lenders. Prompt monitoring and resilient contractual design ease inflation risk detection, management and mitigation, together with proper and flexible financial modelling, alleviating its potentially disrupting impact, especially if unpredictable or chronically enduring.

Keywords: Inflation Risk, Asset/Liability Management, Project Finance, Cost of Capital

Cite this paper: Roberto Moro Visconti , "Inflation Risk Management in Project Finance Investments", International Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 1 No. 6, 2012, pp. 198-207. doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20120106.09.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Inflation risk periodically emerges as an extreme - albeit hardly perceived-event, to which infrastructural investments especially in developing countries are particularly vulnerable, creating disrupting agency costs among different stakeholders. An increasingly wide target audience of both practitioners and academics is interested in the precocious detection, assessment and management of this relevant interdisciplinary problem, so as to find resilient solutions able to mitigate its potentially devastating systemic repercussions. The impact of inflation on discounted cash flows, within capital budgeting investments, has been extensively analyzed, mainly in decades such as the 1970s when inflation was peaking. See for example Van Horne[27]; Nelson[22], Chen, Boness[4], Rappaport, Taggart[23]; Mehta, Curley, Gay[18]; Mills[20]. The sensitivity of cash flows to interest rates - incorporating inflation, if expressed in nominal terms - is a cornerstone of financial statement analysis and corporate finance theory and is well described even in textbooks (see for instance Groppelli, Nikbakht[13], p. 182).The main findings are applicable also to Project Finance (PF), a long-term highly leveraged investment, based on discounted and segregated cash flows. For a statistic of the main PF applications, see Dla Piper[6] and http://online. thomsonreuters.com/DealsIntelligence/Content/Files/4Q10_Project_Finance_Review.pdf.Several kinds of risk concerning PF have been deeply investigated (see for example Beenhakker[2]; Backhaus, Werth Schulte[1], Gordon[11], Zulhabri, Torrance[29], Savvides[24], Miller, Lessard[19], Moro Visconti[21] ) and also the impact of inflation on PF has been analyzed (Dailami, Leipziger[5]; Gatti[10] P. 41; Yescombe[28] pp. 183, 185, 253, 266), even if the current literature still lacks a comprehensive asset & liability framework, where the balance sheet of the PF investing company is linked to its cash flow statement and profit & loss account, showing which are the areas and the stakeholders most sensitive to inflation. The main–still obscure – question is how inflation risk affects PF peculiar investments, influencing their overall affordability and bankability.The methodology of this paper is innovative and significant, going beyond standard literature, which is either focused on inflation or on specific PF issues, proposing practical and useful patterns which start from financial statement analysis, with a consequential interpretation of the economic and financial impact of inflation on a generalized PF model.This paper so fills a relevant gap in the existing literature and its main findings about the impact of inflation on key accounting and financial variables may be flexibly extended even beyond the PF framework, providing useful analytical hints to both academics and practitioners. The impact of inflation on business plans, following standard capital budgeting metrics, does not typically consider corporate governance issues, where different stakeholders are involved: going beyond the classical contraposition between external funders and levered investors, in PF even the public contractor has to be considered. And inflation risk, deriving from unforeseen or imperfect benchmark indexation to price increases, may not necessarily represent a zero sum game, if extreme scenarios have a disruptive “game over” impact.

2. Theoretical Framework

- Macroeconomic risk, mainly referring to inflation and interest rates (or even to exchange rates, if considering foreign projects) is a typical external factor that cannot be influenced neither by the public nor the private part and whose effects may be significant, especially if protracted along time.While interest rates mainly concern the debt burden of the private agent towards its financial backers, inflation is a double edged sword for either the public or the private counterpart (and its financial supporters) within a Public Private Partnership. Indexation with contractual agreements and the level of coverage of inflation changes (up to 100 %) can have an impact on the revenues and costs of the private entity in nominal and real terms, increasing or diminishing economic and financial margins. The same concept applies to the indexation of revenues and costs.When the macroeconomic scenario is perturbed, as it happened starting from the 2008 recession, risk premiums on debt and equity increase, due to the credit tightening following the economic slowdown, and leverage decreases both in its absolute value and in its time extension - shorter projects become increasingly fashionable.In a tax-less world, inflation would presumably only augment both future cash flows and discount rates by comparable amounts (Nelson[22]. See Also Rappaport, Taggart[23].Inflation risk pervasively affects the whole PF model, with a potential damage to the real returns of the private investor; sponsoring banks may also be affected, to the extent that debt service is endangered. Proper factoring of inflation on economic margins and cash outflows and inflows is so a key challenge, with intrinsic relevance and significance.One of the main problems dealing with inflation is due to the very fact that inflation itself is neither a unique nor a stable or easily measurable concept. “General” inflation is typically measured with a Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (combined rate of various baskets of products) but in PF the basket of products and services which form the investment perimeter is peculiar; much depends also on the underlying infrastructural investment: transportation PF investments have an “inflation” that is somewhat different from that of oil & gas or agricultural investments and each needs its tailored made indexes.Inflation, interest rates and foreign exchange rates are linked by well known formulas, such as Purchasing Power Parity, spot/forward parity or Interest Rate Parity. These models show how variables interact, producing a forecast of exchange rates.To the extent that these parities hold, linking expected inflation and interest rate differentials to spot and forward exchange rate adjustments, no arbitrage is possible and the cost of domestic debt underwriting should equal that of foreign debt. To the extent that changes in the value of the local currency vis à vis foreign currencies are related to domestic inflation, foreign creditors/investors will be covered, even if project revenues are in local currency (see Dailami, Leipziger[5] ).Comparing a high inflation developing country to a more stable mature economy, the former is likely to have higher interest and inflation rates, compensated by a devaluating currency. As a consequence, foreign debt underwriting may seem formally cheaper, but its advantage is fully compensated by currency devaluations which make foreign debt service more expensive.

3. Asset – Liability Management Sensitivity to Interest, Currency and Inflation Risk

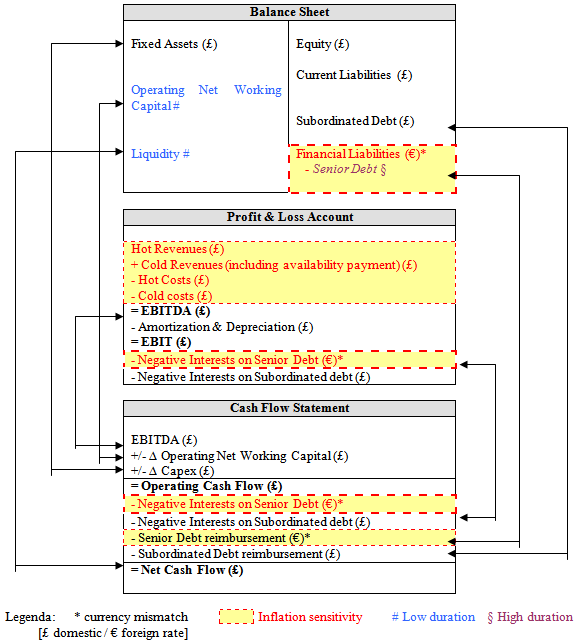

- The economic and financial model of the PF investment is composed by three main interactive spreadsheets, respectively representing the assets and liability statement (balance sheet), the profit & loss account and the consequential cash flow statement. The Asset – Liability management (ALM) model is here briefly introduced with an intuitive graphical representation, stressing its accounting background and so linking it to the interaction of the balance sheet (which represents the core document) with the profit & loss account and the cash flow statement. With this basic approach, it is possible to estimate the economic and financial impact of interest and currency rate mismatches, which originates from assets and liabilities. Interest and currency rates are both linked to expected inflation by the aforementioned models. Risk is consequently generated by currency mismatches and / or sensitivity to market interest rate fluctuations, measured by debt duration.Figure 1 depicts the forex risk, duration and inflation sensitivity, connecting liabilities with economic and financial flows; £ represents the domestic currency and € the foreign one.Asset-liability mismatches occur when their financial terms do not correspond. Consequent financial risk can erode their differential, represented by net equity, through a profit & loss imbalance producing a net loss. When volatility is high and liquidity shrinks, the issue becomes even more important, as it happens during crises and recessions.Imbalances are also due to the different nature and sensitivity of “financial” versus “industrial / operative” assets, liabilities, revenues, costs and cash flows.Traditional hedging strategies consist of careful balancing of assets and liabilities exposure to common risk factors, so as to make them elastically synchronized to external shocks, with little or any impact on the profit & loss and cash flow margins. Exposure to interest rate and currency risk emerges first of all as a result of the imbalances in sensitive assets and liabilities. Even mismatched maturities matter, since their uneven renegotiation follows different pricing pressures. Immunization against interest rate and / or currency risk can be achieved with duration matching, creating a zero duration gap, so ensuring that a change in interest rates will not affect equity value.Since duration declines across time – as debt approaches its maturity – exposure to risk peaks when debt sours, typically at the end of the construction phase, and then slowly starts declining.The international cost of capital issue may conveniently be generalized within an asset & liability framework, where potential mismatching between volatile assets and liabilities may well concern not only different currencies, but also different exposure to (domestic and/or international) interest rates of debt, increasing the cost of collected capital.When PF investments are (at least partially) financed with debt denominated in a foreign - often stronger - currency, exposure to fluctuating forex rates is unavoidable. Due to the aforementioned and well known links between exchange rates, interest rates and inflation, the somewhat capricious interaction of these variables does matter.The “forex mismatch” concerns the balance sheet, the profit & loss account and the cash flow statement. Misalignment occurs not when items denominated in foreign currency are relevant, but rather when they are not balanced by corresponding amounts (and matching maturities) denominated in the same currency, so making the whole structure inelastic to external shocks.

| Figure 1. Forex risk, duration and inflation sensitivity |

4. The Impact of Inflation Risk on Economic Marginality and Financial Sustainability

- The private entity's revenues and costs are typically (fully or partially) indexed to prevailing inflation rates. To the extent that revenues command a positive margin over costs, indexation widens economic marginality. Inflation may so be beneficial for the private entity, especially if it surges beyond expected values and if debt is not fully indexed, so reducing its real face value.“Contractual” inflation differs from “market” inflation, since in the first case the risk is previously agreed by the public and private counterparts – always considering even the sponsoring banks of the latter – whereas market risk is a wider and multilateral exposure to inflation, not always or necessarily regulated by other contractual agreements. The has a potential non negligible impact on the financial and economic margins of the investment and depends on the investment’s object, perimeter and design, referring in particular to the “hot” versus “cold” subdivision of revenues.Since cold revenues for the private part are irrespective of market trends, they bear contractual inflation regulated with revision mechanisms in the PF agreement, sometimes with a (small) discount to full indexation. On the other side, hot (commercial) revenues are fully market driven.The taxonomy of costs is even more complicated: “hot” costs are typically related to “hot” revenues and “cold” costs to the contractual – fixed – remuneration of the investment; but costs concern even depreciation (fully irrespective of inflation, if they are calculated on fixed assets with a not revaluated historical cost), negative interest rates (sometimes floating with basic rates and inflation) and taxes (calculated on a taxable base that is reduced by higher – inflated – interest rates but also increased by devaluated – non indexed – depreciations and higher economic margins…).Interest rates are also linked to inflation and their difference is represented by real rates; to the extent that interest rates are not fully flexible (e.g., fixed rates or even floating rates with a fixed spread), the indebted private entity makes a gain in real terms, its debt being devaluated.Preparing the financial plan, a fixed inflation rate over the whole concession period (construction and management) is typically considered and, albeit this is not the real inflation that will timely occur and be economically and contractually used, bankability may be assessed even taking into account this formal and provisional parameter, to be replaced by real inflation when it timely takes place. According to Van Horne[27]: “In the allocation of capital to investment projects, it is unlikely that optimal decisions will be reached unless anticipated inflation is embodied in the cash-flow estimates”. Being infrastructural PF models typically long termed (up to 30 years or more), cumulated inflation matters and so do inflationary drifts from expected values.Inflation is incorporated in revenues and costs, possibly with different rates – since any item has its own inflation – but in practice typically modelling a “quick and dirty” uniform standard rate. The EBIT (or EBITDA) differential is negatively affected by inflation risk when it shrinks, especially if compared with ex ante modeling (according to which bankability is granted). So inflation risk for the private part may paradoxically be represented by an inflation reduction, more than a surge: if revenues and costs are both timely repriced, year after year, at a lower than expected inflation rate, then the EBIT(DA) differential between operating revenues and costs shrinks, and so consequently does operating cash flow, possibly up to the point of endangering bankability.

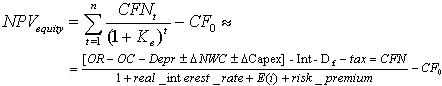

5. Gains or Pains? The Impact of Inflation on the Cost of Collected Capital

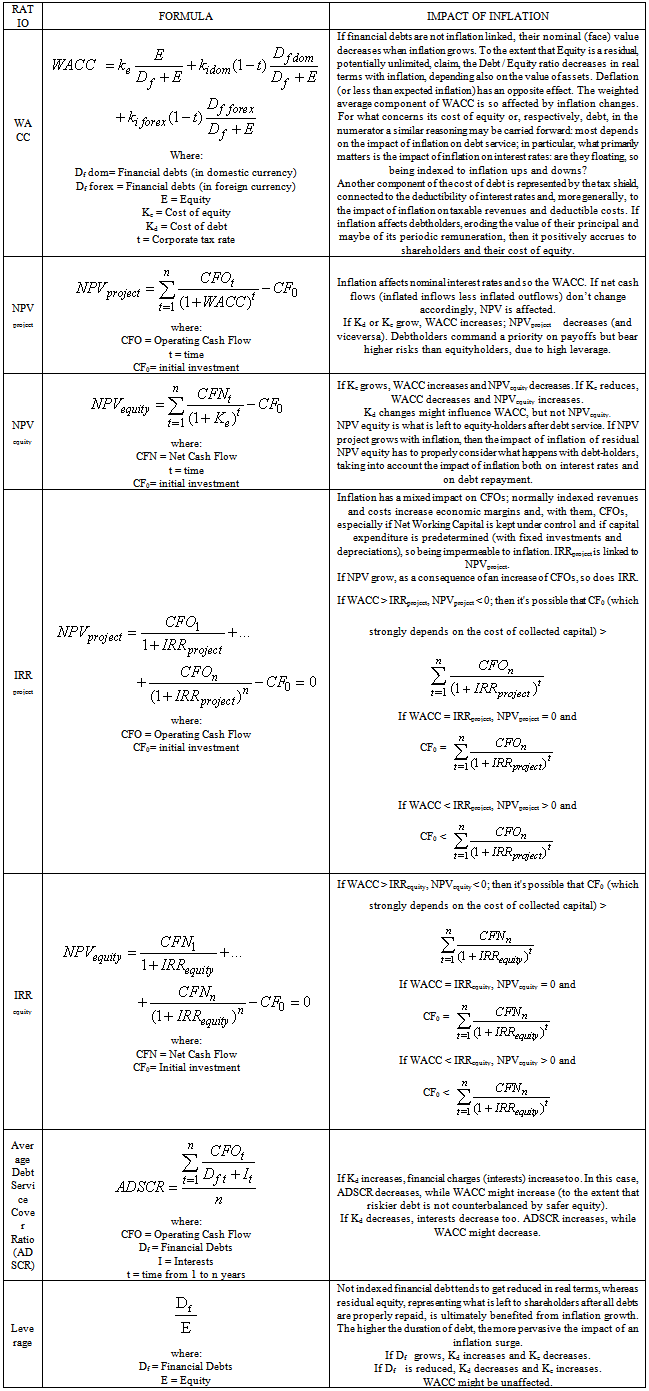

- The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is the rate that a company is expected to pay to finance its assets. WACC is the minimum return that a company must earn on existing assets to satisfy its creditors, owners, and other providers of sources of capital, consisting of a calculation of a firm's cost of collected capital in which each category of capital is proportionately weighted. The WACC is a key parameter in PF, strongly connected with other key financial ratios. When inflation grows, the real – deflated – value of expected cash flows decreases and risk, incorporated in cash flows and (especially) in their discount factor, has to be carefully adjusted for inflation, otherwise both the NPV and the IRR may look artificially “pumped” and distorted by inflated values. Considering the NPV or IRR of equity, it should be noted that inflation has a residual impact: after having affected the assets and the liabilities, it has an ultimate impact on their differential. The statement, only apparently trivial, has important consequences, since shareholders are hardly covered against inflation and the market value of their equity, confronted to its typically not indexed book value, shows if there are gains or losses in real terms. The impact of inflation on the WACC and its related ratios is synthesized in Table 1.The aforementioned key financial ratios interact among them, following sophisticated patterns; if for instance WACC > IRRproject, even as a consequence of inflationary changes, then the project’s financial costs exceed its expected returns and NPV decreases, up to the point of becoming negative, causing an equity as well as a cash burn out. Different kinds of inflation asymmetrically affect accounting, economic and financial parameters, with diverging consequences on different stakeholders:

| (1) |

6. An Empirical Case

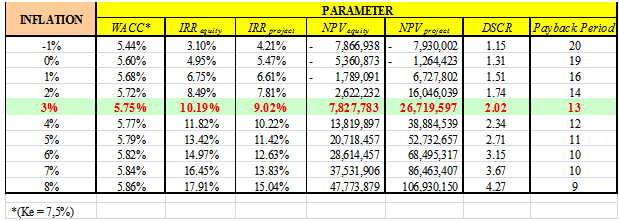

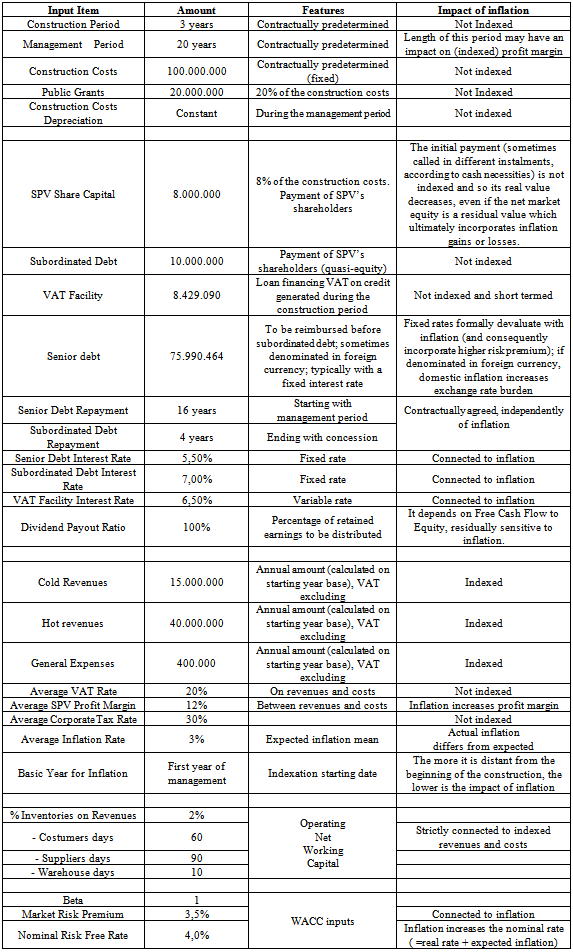

- The pilot model is taken from a real case, conveniently simplified with rounded up figures and basic assumptions, which may be conveniently generalized and applied to practical cases. As far as the author is concerned, there are no similar comparative approaches in the literature, considering in particular the peculiar and highly inflation sensitive PF investment case.The main objective is to assess how the key financial parameters described in paragraph 5 may change – as a consequence of different inflationary patterns, in order to incorporate inflation in the feasibility and bankability assumptions. In each feasibility study, a similar task may be conveniently carried on, not only to ascertain if and to what extent the pilot model is working and bankable, but also which are the break even points (e.g., when the equity NPV reaches zero) which represent an ideal target for the public part: even if private competitors will make bids above this threshold, if competition is effective they will get closer to this point. The general assumptions are summarized in Table 3, while Table 2 contains a sensitivity analysis to inflation changes. The hypotheses, taken from an interactive Excel model, may be subject to basic sensitivity analysis, which could be flexibly adapted and generalized; as it can be seen from Table 3, assumptions are many and may seem complex, even if they nowadays represent a somewhat standard best practice for PF investments. Intrinsic peculiarity of each investment derives from many different parameters (depending on location, currency, industry, type of underlying investment, financial package, composition of shareholders and stakeholders, macroeconomic scenario, etc.), and so case to case adaptation of this paper’s findings has to be carefully undertaken.

|

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The theoretical assumption according to which exchange rates adjust to inflation differentials, so assimilating domestic and foreign funding, is severely challenged by empirical imperfections and deviations from “optimal” international parities, which are in practice very likely and may for instance concern: • Capital rationing, if debt capital, denominated in either domestic or foreign currency is not sufficient or fit for full funding of the project;• Deviations from general price index of peculiar assets, liabilities, revenues and costs;• Asynchronous indexation of (not fully indexed) debt;• Discrepancies between contractual and/or market inflation.Departures from optimal international parities’ assumptions deserve further research, going beyond the scope of this study. Even inflation forecasts, linked to the term structure (yield curve) of expected interest rates, should be further investigated, together with their interaction with currency rates, following a deterministic or a more sophisticated stochastic scenario. While hedging against foreign exchange risk, the private entity has to consider several aspects, such as:• the currency exposure (transaction, operating or economic exposure; translation or accounting exposure);• the kind of foreign currency (from the point of view of the private entity’s shareholders, i.e. the currency of the country that hosts the investment), pegged or not against hard currencies such as the $ or the €.Hedging, even with a Consumer Price Index swap, permits greater leverage (see Leland[16] ) and needs to be periodically rolled over. Indexation mechanisms are the first and most used mean of mitigation against inflation vulnerability - and floating interest rates, albeit difficult to model ex ante, may be used instead of fixed rates. Even inflation-indexed debt can consistently reduce the risk that real returns, after adjusting for inflation, may become negative.

|

|

- Practical adaptation of inflationary impact to different PF investments requires a deep understanding of each business model within its specific industry perimeter. An innovative reference to an asset – liability framework, integrated with the profit & loss account and the cash flow statement, such as that proposed in this paper, may significantly help detect the relevant impact of inflation on PF investments, fostering much desired economic and financial sustainability.Sensitivity analysis is just an introductory step to more complex and pervasive scenario analysis, where several variables simultaneously change and interact; further research is so needed to model more sophisticated scenario patterns, adapting the main findings of a vast empirical literature on price changes to the specific and relevant case of inflation sensitive PF investments. Empirical evidence continuously shows that inflation does matter in PF investment, with significant albeit often concealed transfers of wealth from the public to the private part or vice versa. Unless properly contracted, monitored and managed, inflation may so have a disrupting and unbalanced impact, amplified by the lens of time and going well beyond a simplified zero sum game.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML