-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Finance and Accounting

2012; 1(2): 14-22

doi: 10.5923/j.ijfa.20120102.03

Non-Bank Financial Institutions and Economic Development in Nigeria

Acha Ikechukwu A.

Department of Banking and Finance, University Of Uyo, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Acha Ikechukwu A. , Department of Banking and Finance, University Of Uyo, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Banks are so prominent in the Nigerian economy that non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) are hardly noticed. It is against this background that this study sets out to investigate the role NBFIs play in economic development. It discovered that NBFIs play a fundamental and complementary developmental role in the economy. To assess the impact of NBFIs on the economy the study used data obtained from CBN Statistical Bulletin and the Statistical Directory of the National Insurance Commission. Trend analysis and Pearson’s correlation technique were used to analyse data and test hypotheses. Findings indicate that significant relationship exist between NBFIs credit to the manufacturing and agricultural sectors’ GDP. The same relationship was noted between PMIs credit and the building and construction sector’s GDP. In order to improve on this, fill up structural gaps and utilize their latent potentials, it was recommended that NBFIs should be made more relevant by channelling the Agricultural Credit Guarantee Scheme Fund through them, and they should be further strengthened through recapitalization.

Keywords: Banks, Economic Development, Intermediation, Employment, Recapitalization

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- A close examination of financial literature exposes the lopsided attention paid to banks. While it is awash with information on the scope and intensity of banks’ contribution to the economy, little is said about the input of non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) to development. It is true that banks in a developing economy outclass the NBFIs in volume of transaction, versatility of operations, diversity of products and degree of market penetration (Acha, 2005:1). This does not in any way diminish the contributions of NBFIs as they perform similar functions with the banks and complement the efforts of the banks in the financial intermediation process.Despite their complementary role to banks in the areas mentioned above, NBFIs are known to possess potential advantages in the performance of economic development functions. For instance, certain NBFIs are rural in nature, like the community banks (now microfinance banks), and are therefore able to access greater population of Nigerians and their latent savings potentials. Nigeria is a country in dire need of development and cannot overlook the development potentials of NBFIs.There is therefore the need for close examination of NBFIs to identify the various types operating in Nigeria. This paper also aims at determining the contribution of NBFIs to the economy. It is also within the purview of this paper to assess this contribution with a view to making recommendations that will enable the NBFIs play a more robust role in our development efforts.To achieve the objectives of this paper, theoretical framework is outlined in the next section. This is done by identifying NBFIs in Nigeria and their functions. The third section examines theoretically their role in economic development by assessing their contributions in this direction. The fourth section highlights the problems NBFIs encounter in the performing their developmental roles. In the fifth, data analysis is carried out to empirically assess the impact of NBFIs on development. Finally, recommendations and conclusions are made in the sixth section.

2.Theoretical Framework

- To bring our discussion on NBFIs into proper perspective, we will define, identify institutions that fall within this category and examine their functions. The Banks and Other Financial Institutions Act (BOFIA) 1991 defined non-bank financial institutions as;Any individual, body, association or group of persons; whether corporate or unincorporated, other than the banks licensed under the Act which carries on the business of a discount house, finance company and money brokerage and whose principal object include factoring, project financing, equipment leasing, debt administration, fund management, private ledger services, investment management, local purchase order financing, export finance, project consultancy, pension fund management and such other business as the Bank may from time to time designate. From the foregoing, one can see that the vast operational latitude of NBFIs. This definition goes further to show that functionally, a thin line separates the NFBIs from banks. Furthermore, the traditional difference of banks being the only institution allowed to receive deposits and cheques, drawn on them or paid in by customers, is further whittled down by the inclusion of Community Banks, Primary Mortgage Institutions (PMIs) and Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) as NBFIs (Bamisile, 2004:42). This recent inclusion of these other institutions as NBFIs as highlighted above further increased the scope of NBFIs operations and their relevance in catalysing economic development.With this new development, we can identify the following NBFIs operating in Nigeria. Finance companies, community/microfinance banks, bureaux de change, discount houses, development finance institutions, insurance companies and primary mortgage institutions. At this stage, it is pertinent that we examine each of them with the intent of functionally understanding their mode of operations. i. Finance Companies: Finance companies engage in short term non-bank money lending, leasing, hire purchase, factoring, LPO financing, export financing, electronic funds transfer and issue of vouchers, coupons, credit cards and token stamps. As finance companies are not authorized to mobilize deposits from the public, they rather rely on owners’ equity and borrowings to perform their intermediation role. They are known to play active role in financing small and medium scale enterprises (Onoh, 2004:105). ii. Community Banks: These are self-sustaining financial institutions owned and managed by local communities such as community development associations, cooperatives, town unions, individuals etc. Unlike commercial banks, community banks are unit banks but they can accept deposits, grant credit to their customers and provide limited banking service (Iorchir, 2006:15).They are not allowed to participate in the foreign exchange market neither do they belong to the bank clearing system. To circumvent this rule many community banks develop correspondent relationships with commercial banks to enable them clear cheques. Community banks play active role on rural development by mobilizing rural savings and financing investment at the grassroots (Bamisile, 2004:43). Most of these banks have metamorphosed into Microfinance banks and those of them that could not meet the recapitalization requirement were liquidated (Mobolurin, 2006:24; Isa and Adesokan, 2007:2).iii. Bureaux De Change: In the opinion of Obadan (1993:371) the advent of bureaux de change was predicated on government’s desire to correct the shortcomings identified in the operations of black marketers. These parallel markets operators were buying foreign exchange at very low prices only to turn around to sell at very high prices. It was in a bid to control their activities that the government brought them under the supervisory purview of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). They are therefore authorized to buy foreign currency from the public and not from banks (Akpan, 1999:37). Through their operations bureaux de change help to attract hard currency into the country by offering prices better than the official rate and by availing Nigerians abroad who remit monies home a channel to do so. Through this avenue, they boost the foreign exchange reserves of the country and improve the economy ultimately.iv. Discount Houses: The first set of discount houses began operations in Nigeria in 1993. They were established to act as intermediaries between the CBN, the licensed banks and other financial institutions. They mobilize funds for investment in securities by providing discount/rediscount facilities in government short-term securities. By so doing, they facilitated the use of indirect monetary policy tools especially open market operations. Apart from improving the efficiency in monetary policy administration, discount houses have also positively impacted on banks’ liquidity, by providing banks an investment outlet for their surplus funds (Agene 1991:108). v. Development Finance Institutions: Development finance institutions (DFIs) popularly known as development banks are specialised institutions established to foster development in specified sectors of the economy. To improve the performance of these institutions government has re-organised them. As part of this re-organization process, government brought them under the supervision of the CBN and merged some of them. The Nigerian Industrial Development Bank (NIDB), the Nigerian Bank for Commerce and Industry (NBCI) and Nigerian Economic Reconstruction Fund (NERFUND) were merged to form the Bank of Industry (BOI). Also, the Nigerian Agricultural and Cooperative Bank (NACB), the People’s Bank and Family Economic Advancement Programme (FEAP) were brought together to form the Nigerian Agricultural Cooperative and Rural Development Bank (NACRDB). Akpan (1999:30) identified the need for the provision of long term loans to encourage investment and aid economic development as driving force behind the reorganisation of these institutions. He further pointed out that apart from making loans available, these institutions also extend technical and managerial expertise to the loan beneficiaries.vi. Insurance Companies: These are institutions that undertake to indemnify their customers from economic loss. They mobilize savings through the premium paid by the insured; from this pool of savings they are able to indemnify the few that suffer loss. Insurance plays a very active role in development, (apart from the psychological assurance it gives to investors). It also plays an active role in capital formation and remains a veritable source for long-term development funds (Harrington and Niehaus, 1999:196; Dorfman, 2005:2). Insurance business consists of life, non-life as well as re-insurance. Despite insurance being the second most important financial institution the industry suffers from poor image and low patronage attributed to poor indemnification process and protracted legal tussle (Akpan, 1994:242). It is believed that the recapitalization in the industry will strengthen them, improve their management, enthrone good corporate governance and ultimately improve their image (Acha, 2007:64).vii. Primary Mortgage Institutions: Primary Mortgage Institutions (PMIs) mobilize long-term funds for the development of housing (Onoh, 2004:113). The National Housing Policy launched by the government in 1992 was aimed to boost activities in this sector. Workers in public and private sectors, banks, insurance companies were mandated to contribute to housing development. These funds were to be lent to PMIs by the Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria (FMBN) for on lending. The PMIs apart from mobilizing funds of their own also serve as a conduit through which National Housing Policy loans pass to beneficiaries. Umoh (1997:39) opined that PMIs have not made any appreciable impact in the housing finance market. This he attributed to their unfaithfulness to their operational scope by lending to non-housing businesses. Another factor that has impeded their performance is the paucity of long-term funds in the financial market (Bamisile, 2004).

3. NBFIs and Economic Development

- The primary channel through which NBFIs assist in economic development is the intermediation process. They mobilize funds by various means open to them and make same available for investment.Finance companies for instance make available funds raised through owner’s equity contribution and borrowings from other financial institutions, individuals and companies, to investors. Community banks like commercial banks, mobilize deposits from customers in form of savings, current and fixed deposits, insurance companies on the other hand aggregate the premiums paid by policy-holders. Apart from mobilizing their own funds, some NBFIs obtain significant grants and loans from the government and international financial institutions for onward lending. The NBFIs that fall under this last category are development finance institutions and primary mortgage institutions. The foregoing aptly articulates the investment funds generating abilities of NBFIs (Onoh, 2004:106).In addition to their contribution to economic development through investment funding, NBFIs like bureaux de change encourage capital inflow. By offering higher rates than the official rate of exchange, citizens working abroad are thus encouraged to remit monies home. Since transactions in bureaux de change are carried out anonymously, citizens resident abroad who wish to bring foreign exchange without passing through official channels are given avenues to do so. The increased inflow of foreign currency which this engenders improves the country’s Gross National Product (GNP) and by extension general economic well-being is enhanced (Aghoghovbia, 2006:73).Housing is one of man’s basic needs and its availability is a measure of his economic well-being. In the light of this, the role of primary mortgage institutions in housing development is of significant economic importance. Whether they are disbursing funds they generated or those from the National Housing Fund, their underlying developmental impact is in making houses available and affordable to Nigerians (Sanusi, 2003:4).Equipment financing and industrial infrastructural development is in the domain of development finance institutions. From funds which they obtain as grants from governments or loans from international financial institutions such as World Bank, these development finance institutions fund long-term real investments. They further contribute to economic progress by providing advisory services, technical and managerial expertise to such projects.The role insurance companies play in economic development is strikingly outstanding. Apart from being a veritable source of long-term funds, it also possesses an unquantifiable psychological assurance, allaying the risk and loss anxieties of investors. This assurance kindles local entrepreneurial spirit and encourages foreign direct investment. By indemnifying policyholders in case of actual loss, insurance companies ensure production continuity and the maintenance of established consumption patterns and hence improvement of existing living standard (Pritchett, et al, 1996: Isimoya, 2003:1).Another area where NBFIs have played a vital developmental role is in the reduction of money stock outside the banking system. Akpan 1998:30 rightly pointed out that due to the existence of a grossly under banked rural economy, monetary policy measures instituted by CBN are ineffective. The advent of community banks and their rural focus has gone a long way in correcting this anomaly. The community banks and recently microfinance banks have been able to mop up substantial rural deposits, monies which hitherto remained outside the banking system and hence outside the control of monetary authorities. Monetary policy which is geared towards varying money supply to check inflation and enhance rapid economic development has through the instrumentality of these banks become more effective (Ojo, 1994:10).Provision of a secondary market for trading in government securities by discount houses through their discount activities has also immensely contributed to the effectiveness of monetary policy especially Open Market Operations (OMO). The presence of an avenue to discount these securities encourages banks and other investors to buy them, by so doing government is provided with development funds on one hand and open market operations became more effective as a monetary policy instrument on the other. Increased activity has been recorded in the market since the advent of the discount houses in 1993; this has improved financial structures and further deepened the financial system (Oke, 1993:15; Oresotu, 1993:158).NBFIs contribute to the amelioration of the massive unemployment experienced in the country. Apart from those directly employed to work for them, there is a teeming number of unemployed graduates, artisans, farmers, etc who establish businesses from credit made available by NBFIs. Their funding of small and medium scale enterprises is also a boost to employment as these enterprises are known to be the highest employers of labour in our economy.

4. Problems of NBFIs

- The development potentials of NBFIs are impeded by a myriad of problems that confront them. Some of these are systemic while others are endogenous. A few of these problems are discussed below:i. Distress. The financial distress of the 1990’s thoroughly decimated the ranks of NBFIs. Several NBFIs (Community banks, PMIs, Finance companies, etc) became distressed during this period and were subsequently liquidated.The distress experienced by the NBFIs could be attributed to several reasons. Some of which include inadequate capitalization, poor management and illiquidity. The harsh economic environment and the distress of banks which some of them had dealings with also contributed immensely to the problems of NBFIs.ii. Funding. Some NBFIs like DFIs were used to government subventions and international aids. When government subventions dried up and international donors were not forthcoming, these NBFIs became moribund. It was this situation that gave the present government the impetus to reorganise this sector by merging some of them.iii. Operational Deficiency. The policy establishing community banks envisaged a financial institution that will engender economic development by funding small and medium term enterprises without attaching the commercial bank kind of stringent loan conditions. This policy though laudable did not take our societal value system into consideration, as most of the entrepreneurs that benefited from these uncollaterized loans refused to repay. Their refusal compounded the problems of these NBFIs.The case of the DFIs was not much different but in their own case being government establishments the loan beneficiaries saw it as their own share of the “national cake” ((Alashi, 2002:49).iv. Capitalization. Most NBFIs were established with very little capital. Those that were adequately capitalised had their capital base eroded by bad debt. The inadequate capitalization made it impossible for these institutions to withstand economic shocks and losses. In the case of community banks, the initial recommended capitalization was as low as N250, 000.00. This allowed nefarious characters and criminals apply for licenses which they used to dupe unsuspecting depositors. This may have informed the capitalization review in the case of microfinance banks to N20m and one billion naira for unit and state-wide microfinance banks respectively.v. Competition. With the deregulation of the Nigerian economy in the mid 1980’s there was a tremendous upsurge in the number of banks and NBFIs operating in Nigeria (Acha, 2004:128). This increase in number engendered keen competition among them for deposits. NBFIs most of them being smaller and with fewer branches or no branches at all, as in the case of community banks, could not therefore compete effectively with the banks.

5. Data Presentation and Analysis

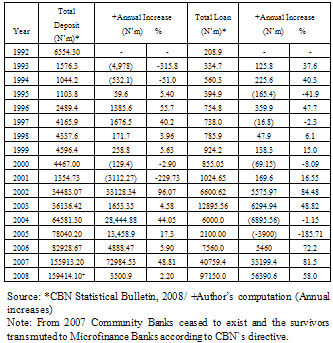

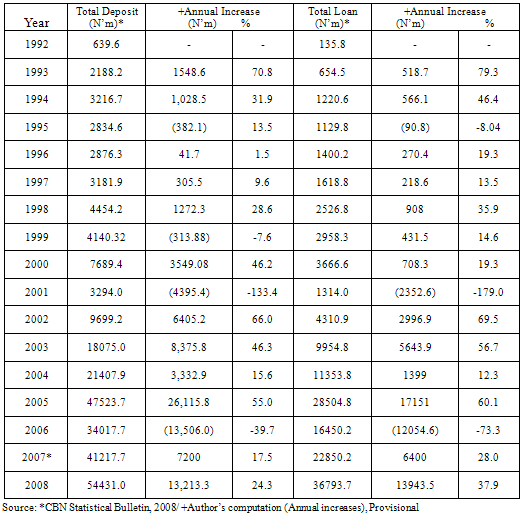

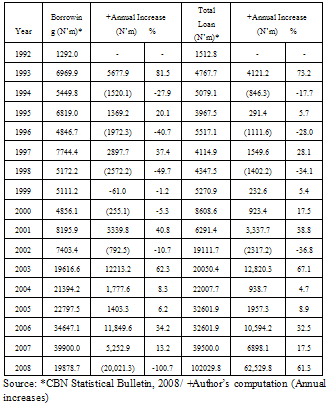

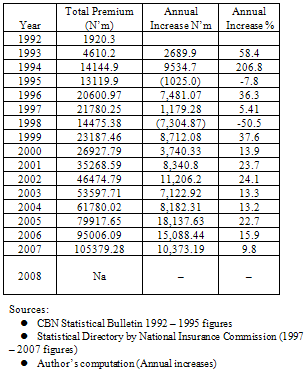

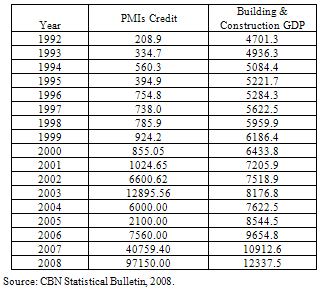

- Having observed earlier that the main channel through which NBFIs contribute to economic development is the intermediation process. We will proceed to vividly illustrate the extent of this contribution by the NBFIs in Nigeria using facts and figures.The contributions of community banks, primary mortgage institutions, finance companies and insurance companies would be examined. It is also important that we note that in line with CBN policy community banks have since 2007 transmuted into microfinance banks.

|

|

|

|

5.1. Hypothesis Testing

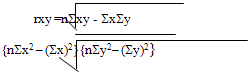

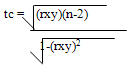

- To further examine the contribution of NBFIs to economic development, analysis of the relationship between their credit to the economy and gross domestic product (GDP) is made here. The idea is to establish if the facilities they extended to the various productive sectors of the economy had any positive impact on them. To achieve this, the following hypotheses are formulated for testing.i Ho - There is no significant relationship between NBFIs credit to the economy and the agricultural sector’s contribution to GDP.ii Ho - There is no significant relationship between NBFIs credit to the economy and the manufacturing sectors’ contributing to GDP.iii Ho - There is no significant relationship between PMIs credit to the building and construction sector and the GDP of that sector.Pearson’s correlation technique is adopted to establish relationships between the variables and students‘t’ test was used to test the significance of relationships established. For Pearson’s correlation coefficient and decision rule see below:i Pearson’s correlation coefficient

ii Decision rule:Accept Ho: if tc < ttReject Ho: if tc > ttDegree of freedom = n-2 = 8Level of significance = 5%tt for 2 tailed test = 1.86where

ii Decision rule:Accept Ho: if tc < ttReject Ho: if tc > ttDegree of freedom = n-2 = 8Level of significance = 5%tt for 2 tailed test = 1.86where

5.1.1. Test of Hypothesis I

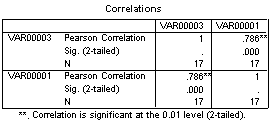

- Hypothesis Tested:H0:There is no significant relationship between NBFIs credit to the economy and agricultural sector’s contribution to GDP.H1:There is significantly relationship between NBFIs credit to the economy and agricultural sector’s contribution to GDP.Correlations Result:

|

|

5.1.2. Test of Hypothesis II

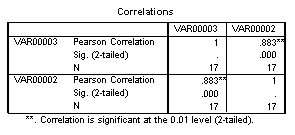

- Hypothesis Tested:H0:There is no significant relationship between NBFIs credit to the economy and manufacturing sector’s contribution to GDP.H1:There is significantly relationship between NBFIs credit to the economy and manufacturing sector’s contribution to GDP.Correlation results:

|

5.1.3. Test of Hypothesis III

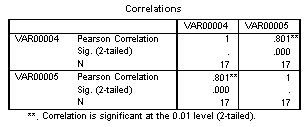

- Hypothesis Tested:H0:There is no significant relationship between PMIs credit to the building and construction sector and the GDP of that sector.H1:There is significant relationship between PMIs credit to the building and construction sector and the GDP of that sector.Correlation Result:

|

5.2. Findings

- Pearson’s correlation coefficient showed strong positive relationship between NBFIs credit and Agriculture sector’s contribution to GDP. This position was confirmed by the student‘t’ test which established that this relationship is significant. This implies that agricultural sector is getting the much required.Also a significant positive relationship was established between NBFIs credit and the manufacturing sectors GDP. Same scenario played out between PMIs credit and building and construction sector’s GDP, giving rise to the rejection of the null hypotheses. The implication of that is the credit of NBFIs and PMIs contributed significantly to these sectors’ productivity.

|

6. Summary, Recommendations and Conclusion

6.1. Summary of Findings

- A close examination of the statistics pertaining to various NBFIs existing in Nigeria confirmed their developmental role. Literature had expressed the notion that NBFIs contribute to economic development via the intermediation process. Facts as revealed by statistics confirmed this assertion as all the NBFIs assessed were seen to mobilize substantial amount of funds from surplus economic units in form of deposit, borrowing, premium, etc for onward lending to the deficit economic unit as loans, investment etc. Apart from this, the NBFIs are known to also contribute to economic growth through other avenues like reducing financial dualism, increasing efficiency of monetary policy instruments, making houses available to Nigerians, encouraging entrepreneurial zeal by reducing risks and by deepening the financial system.

6.2. Recommendations

- Having highlighted the contributions of NBFIs to the economy, this section seeks to suggest ways to improve their structures and operations to make them more efficient and by extension contribute even more to the development of our economy. With this in mind, the following suggestions are made;i. The CBN should organize a clearing system for microfinance banks. This will enable them play more active role in the money market and not continue to operate at the mercy of their correspondent commercial banks. Some of these correspondent banks are known to slow down the microfinance banks with conditionalities, commissions and other charges in order to boost their own profitability and reduce competition from these banks.ii. Primary Mortgage Institutions should be made to play a more robust role in housing delivery to Nigerians. A situation where PMIs are forced to operate in the short-term financing market due to the paucity of long term funds is unacceptable. To encourage them to play their main role of providing long-term funds for housing development, long term funds should be made available to them. The pension deductions made from workers’ salaries could be a veritable source of mortgage financing.iii. The restructuring and consolidation as done in the insurance industry should be extended to the other NBFIs if they are to remain competitive. The recapitalization in the insurance industry is a step in the right direction. Other NBFIs should follow the cur. Recapitalization will bring about consolidation through mergers and acquisition this will strengthen the NBFIs and position them for better service delivery.iv. Close examination of the operations of insurance companies is advocated. Claims settlement is the aspect of insurance identified in literature as steeped in malpractice. This discourages potential insured from taking up policies.v. To improve NBFI’s credit extension to the agricultural sector, microfinance banks many of which are rural based can be incorporated into government’s agricultural credit guarantee scheme (ACGS). This way microfinance banks will not only be encouraged to lend to agriculture but these funds will reach actual farmers and the inconveniences of their having to travel long distances to process these loans would be arrested.

6.3. Conclusion

- This study started by identifying the various NBFIs operating in Nigeria. It went further to highlight the roles they play in economic development. In so doing the functions of various NBFIs were examined and their contributions to economic development x-rayed.It was discovered that despite the enormous contribution of NBFIs to the economy that most of its potentials in this direction remains untapped. Based on this, recommendations were made which implementation is expected to strengthen the NBFIs, improve their competitiveness and increase their contribution to economic development.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML