-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Ecosystem

p-ISSN: 2165-8889 e-ISSN: 2165-8919

2025; 14(1): 1-21

doi:10.5923/j.ije.20251401.01

Received: Apr. 22, 2025; Accepted: May 13, 2025; Published: May 17, 2025

A Reflection on Environmental Planning Policies in Africa from the Perspective of the Tree Planting Initiatives

Emmanuel Samson Honore Lobe Ekamby1, 2, Pierpaolo Mudu3

1Department of Geography, Bonn University, Meckenheimer Allee 166, 53115 Bonn, Germany

2Institute for Environmental Risks and Human Security, United Nations University (UNU-EHS), Platz der Vereinten Nationen 1, 53113 Bonn, Germany

3Public Health, Environmental and Social Determinants of Health (PHE), World Health Organization (WHO), Avenue Appia 20, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland

Correspondence to: Emmanuel Samson Honore Lobe Ekamby, Department of Geography, Bonn University, Meckenheimer Allee 166, 53115 Bonn, Germany.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Environmental planning policies in Africa on tree-planting projects have taken on an increasingly important role. These projects have garnered significant political and media attention as simple, impactful planning solutions for the environment and societies. They are important to discuss not only for their role but also for the expected improvements in addressing climate change, controlling desertification, and promoting the well-being of populations. Tree projects in 54 African countries were analyzed, focusing on the so-called National Tree Days. National Tree Days are official days when Heads of State and government officials inaugurate and celebrate tree-planting activities. Some projects have been highly publicized, but little monitoring and evaluation have been implemented. Consequently, in African countries, several critical points emerge on planning if we focus on the role of green infrastructure because of its potential social benefits and supportive capacity for sustainable planning. While cities have been extensively studied, peri-urban and rural areas, where most Africans live, are often overlooked. This paper provides background on relevant processes in African peri-urban and rural areas, focuses on National Tree Days, discusses a classification of tree planting projects, and debates how these projects influence environmental planning. Several critical points emerged, suggesting a serious rethinking of planning activities.

Keywords: Trees, Africa, Ecosystem services, Rural and peri-urban greening

Cite this paper: Emmanuel Samson Honore Lobe Ekamby, Pierpaolo Mudu, A Reflection on Environmental Planning Policies in Africa from the Perspective of the Tree Planting Initiatives, International Journal of Ecosystem, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-21. doi: 10.5923/j.ije.20251401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- For many decades, Africa has experienced both massive deforestation and forest burning due to intensive human activities, such as agriculture and lumbering and wars. According to UN statistics, Africa had the highest net loss of forest area in 2010-2020, with approximately 4 million hectares per year [1]. Many tree-planting projects have been announced by African governments as measures to combat climate change, desertification, biodiversity loss, reduce pollution and promote health and well-being on the continent. These tree-planting projects are encouraged by authorities, with an emphasis on the expected benefits [2]. African cities are hosting several tree projects, mostly initiated by governments, local authorities, and non-governmental organizations, to provide new green spaces and trees for their inhabitants [3,4]. Most of the analysis of projects is available from only four nations, South Africa, Ethiopia, Ghana and Nigeria [5]. But, there are also announcements of tree projects in rural and peri-urban areas where the greater share of the population lives despite Africa’s rapid urbanization rate, since about six out of every ten persons in Sub-Saharan Africa lives in rural areas [6,7]. The international character of many trees planting projects derives from different pledges and engagements made on forest protection and restoration during recent international summits such as the Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings on climate change (convened under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – UN-FCCC), on desertification (convened by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification – UNCCD), and Biodiversity (organized by the United Nations Environment Programme – UNEP). For instance, at Climate COP 26, the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use was signed by about 142 countries. During this conference, commitments were made for the protection and restoration of forests, particularly in developing countries that are the ones contributing far less to climate change compared to high income countries. Specifically, high-income countries pledged approximately USD 12 billion for forest-related climate finance between 2021 and 2025 [8], while Africa received a pledge of USD 1.5 billion to protect the Congo Basin Forest for the period of 2021-2025 [9].The African continent comprises fifty-four countries with a total population of approximately 1.5 billion. While it is challenging to provide a comprehensive overview of the entire continent, it is important to highlight that many analyses on Africa overlook issues such as war and conflicts, migrations, social inequalities, and health conditions.African countries are involved in several armed conflicts, specifically: international armed conflicts, military occupations and non-international armed conflicts are 39, involving 17 countries, “Africa has been the continent with the highest number of state-based armed conflicts since 2015. The number steadily increased during 2018–20 [10]. However, this trend changed in 2021, with the number of conflicts dropping from a record high of 30 in 2020 to 25 in 2021 [11] (p.596). Armed conflicts continue to cause significant displacement in Africa, with many refugees coming from countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Somalia, and the Central African Republic. Uganda hosts nearly 1.5 million refugees, the Sudan nearly 1.1 million and Ethiopia nearly 900,000 [12].An increasing number of Africans migrated and are living in another African country, around 21 million in 2020, while they were 18 million in 2015 [12]. To put this in a global perspective, it must be considered that in 2020, African-born migrants living in Europe were 11 million, around 5 million in Asia and around 3 million in Northern America [12]. This relevant migration pattern has consequences for rural Africa [13]. Often migrations from rural areas end up in peri-urban and urban slums that in sub-Saharan Africa host more than 50% of the population. And the number of households living in slums in sub-Saharan Africa has been growing from an estimated 131 million in 2000 to approximately 230 million in 2018 [14]. Additionally, Africa hosts significant nomadic populations, for example dedicated to mobile pastoralism [15]. Land grabbing and commons grabbing has also been a significant feature for African populations after colonialism and under pressure by dominant neoliberal policies [16].Nevertheless, improvements in the health conditions of populations have happened. In the 47 Member States of the WHO African Region life expectancy increased from 47.1 years in 2000 to 56.1 years in 2019 [17]. The population with impoverishing health spending at the PPP $1.90 a day line of extreme poverty has decreased over the years, by 17.2 percentage points [17]. In the WHO African Region, for the health system service coverage significant progress was observed between 2000 and 2019 in many countries [17]. But across the African Region, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the delivery of essential health services [17]. Catastrophic health spending, when people spend more than 10% of their household budget out-of-pocket on health, regardless of their poverty status, has increased in the last 20 years [17]. The environmental situation of Africa is very serious. The forestry and agricultural sectors generate a significant source of air pollution, at local and international scale, due to bush and grassland fires, and the largest emission growth rates are expected in Africa [18] where “slash-and-burn is one of the most common practices employed by farmers on the continent to clear their land.” [19] (p.5). The air pollution from these fires has not only a local and regional impact but also a global effect on, and they are estimated to contribute up to a third of the Earth’s biomass-burning aerosol particles [19]. These emissions are also estimated to cause more than 43,000 premature deaths on the continent each year [20]. Ambient air pollution-related mortality has increased from 26 per 100,000 in 1990, to 29 per 100,000 in 2019 [21]. Africa presents the vast majority of areas burned per year, that is more than 70 percent of the global burned areas [22]. Many scholars recognized the challenge of clearly differentiating rural from urban areas. For many years, the widest criteria were the size and density of the population. However, what is small or dense in one country may be viewed as large and spare in another [6]. Another criterion is the nature of economic activities carried out in both human environments. Usually, areas dominated by agriculture are regarded as rural with a sparse population while areas dominated by commerce and industry are seen as urban areas mostly with a highly dense population [23]. However, despite making a general difference between rural and urban areas, it is challenging to define them in an African context [24-26]. In fact, it will be misleading to consider African rural areas like those in Europe and Asia [27]. In general, the land use development is very different: Africa, with about 10% of its land covered by urban areas and towns, is dominated by sparse villages, differently from Asia, Europe and North America, that have nearly 30% of urban land [25]. Land rights are usually unregistered, and indigenous populations and local communities struggle to control their land [28]. African rural areas frequently lack access to public transport, electricity and water. Population in rural areas utilize forests and other natural, non-cultivated environments for living and generating a significant income [29]. There are cases where rural villages develop into boomtowns because of mining activities or dynamics of violence and forced displacement, for example in Angola, DRC, Mozambique and Zambia [30]. African rural areas have unique characteristics that set them apart from other regions, Europe in particular, due to their significance in national development and the well-being of the people [6]. These areas can include tribal lands, commercial farms, and informal settlements [31]. Another issue to identifying rural areas is given by the fact that Africa has over 15% of its land protected as national parks or reserves [32]. According to the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), there are more than 9,000 protected areas in Africa, but most of them are small in size [33]. Rural Africa encompasses diverse climate zones, some of which are affected by desertification, soil degradation, pollution, water scarcity, and low crop yields, while others are located in tropical zones. Forest reserves in the past have had a negative connotation for being associated with providing refuge for troops during wartime, for example in Burundi [34] or being havens for criminal activities, and, for example, the Karura Forest was before 2009 viewed as a dangerous location [35].This paper focuses on lessons learnt for planning after an analysis of policies of announcements of planting trees, in particular by considering the National Tree Days, as it is impossible to have an exhaustive list of tree planting projects and we recognize that an exhaustive list of tree-planting projects that are proclaimed or implemented in rural and peri-urban Africa is quite difficult. Their number is too big, in many cases the information is absent, and often they are targeting very small-scale interventions. Nevertheless, Africa is hosting some of the world’s ambitious project like the Great Green Wall Initiative (GGWI) and the narrative on tree planting has increased over the years. Although our overview does not encompass all the information pertaining to tree planting initiatives in Africa, we believe that our collection of data, albeit partial, provides valuable insights into noteworthy recent projects and trends. The objectives of this paper are: 1) to offer an overview of the most relevant policies of announcements of planting trees in Africa, in particular by considering the National Tree Days or National Arbor Days and focusing more on rural and peri-urban projects, and their characteristics, than on urban projects; 2) to offer to discussion an articulated analysis, with data and examples, of the implications for planning that trees planting projects have in Africa and 3) advance on the conceptualization on the planting trees rhetoric that is often not producing the announced benefits.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Tree Planting Projects in Rural and Peri-Urban Africa

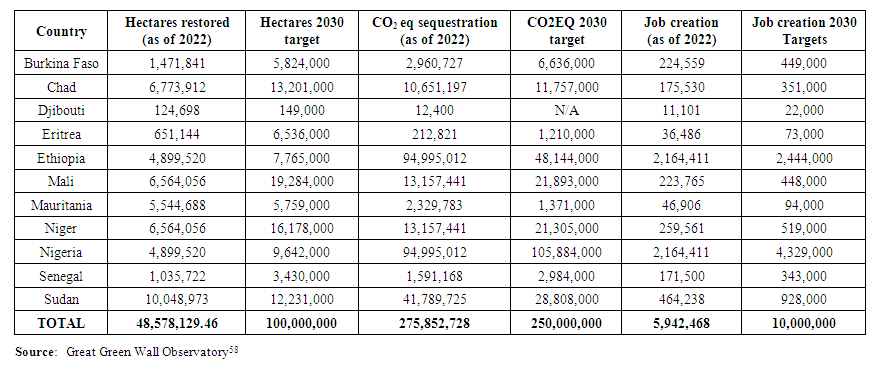

- Information on tree-planting projects in African cities and urban forestry have been analyzed [2,3,4,36,37] but is less known about these activities in non-urban Africa. Planting trees in rural and peri-urban areas of Africa has been ongoing for both commercial and personal purposes in villages. Governments officials have made public announcements regarding reforestation and afforestation projects in various countries, which have garnered significant media attention. While reforestation projects are mostly initiated in countries with rainforest climates, afforestation projects are typically carried out in countries with semi-arid and/or arid climates. It is important to recognize that reforestation is promoted by countries that have experienced significant forest cover loss due to deforestation and illegal tree logging, such as those in the Congo Basin Rainforest. Conversely, afforestation is encouraged by governments whose countries have been affected by extreme heat and global warming, resulting in desertification and drought, such as those in the Sahel and North Africa. Additionally, many African countries have both arid and rain-forest climates, with regions experiencing extreme climate patterns and populations facing climate-related risks. The GGWI is the largest and ambitious ongoing project in Africa, which was launched in 2007 with the participation of 22 African countries under the supervision of the African Union and the UNCCD [38]. This project aims to combat desertification and revitalize thousands of communities, mostly in rural areas, by restoring “100 million hectares of degraded landscapes, sequester 250 million tons of carbon dioxide, and create 10 million green jobs by 2030” (see Annex). The Great Green Wall Accelerator was introduced at the One Planet Summit in 2021 to address the ongoing delay in achieving the expected results of the decade-old project [39,40]. Despite the initial commitment of USD 8 billion, the lack of sufficient funds has been a major hindrance to the implementation of the massive green initiative. For instance, Senegal has invested 8 billion CFA Francs (approximately 13 million USD) between 2008 and 2015 in the Great Green Wall [41]. Other international initiatives are AFR100 – The African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative that is a country-led effort to restore Africa’s degraded and deforested land (see Annex). AFR100 involves 34 countries bringing 100 million hectares of land across Africa into restoration by 2030 [42]. For both the two big pro-jects of the GGW and AFR100 some indicators of progress are available in the Annex.

2.2. Data Collection

- In the next sections, we examine data from the most recent tree planting initiatives that were carried out between 2012 (year of the proclamation of 21 March as the International Day of Forests by the United Nations General Assembly) and 2023, as well as information on the declaration of National Tree Days in Africa. The data on tree planting policies in Africa were gathered over the course of one year from a diverse range of sources. The specific methods used to collect this data are outlined in the Annex. Our database provides a first list of initiatives that can be re-analyzed, corrected and expanded by other scholars (see the Annex).

3. Results

3.1. A summary of Key Planting Tree Projects in Rural Africa

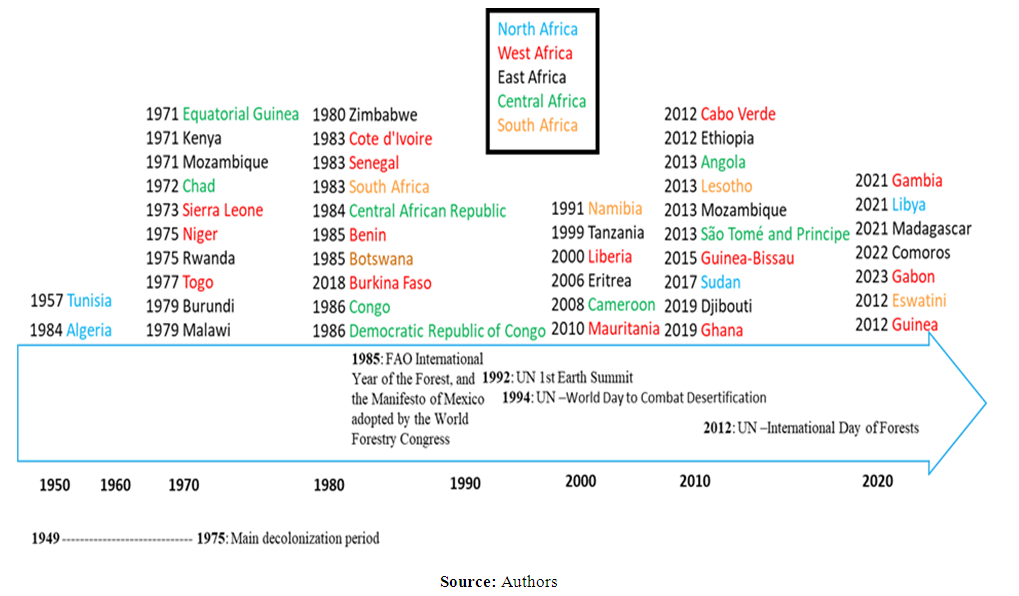

- Since the beginning of the 21st century, national tree planting days have emerged in several countries. The year that each country adopted its national tree day gives information on how much there has been an acceleration on a global agenda. In 21 countries in Africa, the National tree days were proclaimed in the decades 1970-1990, in one third of the cases, the countries in central and East Africa, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya, Mozambique, Niger, Rwanda and Sierra Leone proclaimed it in the early 1970s (following the FAO “World Forest Day” proclamation), while many other countries (Zimbabwe, Cote d'Ivoire, Senegal, South Africa, Algeria, Central African Republic, Benin, Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo) proclaimed it in the 1980s. The majority of countries proclaimed it after the year 1990, and the majority after the “International Day of Forests” proclamation (see figure 1). In two cases, in Tunisia and Algeria the proclamation happened before 1970. The proclamation of these days happens for various reasons including aligning with international agendas, making large ecosystem investments, and fostering national patriotism. These reasons are not mutually exclusive. The celebration of tree planting days involves projects of different sizes and goals, with the number of trees planted ranging from a few to billions. We provide examples of projects initiated to align with international agendas, large-scale projects, as well as projects aimed at national mobilization or nature protection.

| Figure 1. Proclamation of the national tree days (Journee de l’arbre, Dia da Árvore, día nacional del árbol) in Africa |

3.2. The International Agenda

- The calendar for planting trees follows mainly an international input and besides the GGWI national initiatives are often originated by international resolutions. The International Day of Forests, meant to raise awareness and celebrate the importance of all types of forests, is celebrated on March 21st in some countries, coinciding with the national arbor days. This date was established by the United Nations General Assembly on November 28, 2012, through a resolution that proclaimed March 21st as the International Day of Forests, following the declaration of World Forest Tree Day by FAO. The International Day of Forests is widely celebrated across many African countries, with approximately 12 countries recognizing it as their National Tree Day. These countries are Angola, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Eswatini, Gabon, Guinea Bissau, Lesotho, Morocco, Mozambique, São Tomé and Principe. Additionally, some countries organize their National Tree Day activities on the 5th of June, which also happens to be World Environment Day. These countries include Guinea, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan, among others. Finally, there are countries (like Nigeria) whose National Tree Day is celebrated on June 17th, which coincides with the World Desertification Day. Some countries such as Chad and Mauritania proclaimed a National Tree Week, South Africa a Arbor month, and in the case of Malawi and Zambia an entire season is devoted to planting trees (see Annex). Also, small countries, such as Djibouti or Eswatini have plans of planting trees (see Annex). For example, in Eswatini 10 million National Tree Planting programme was launched by the Prime Minister in 2020 [43] and on 29 October 2022 in Rwanda on the 47th anniversary of the National Tree Planting Day, the activities of celebration in the peri-urban area of the Gasabo district announced the target of planting more than 36 million trees [44].Tree-planting activities also take place in countries as part of sports events such as the Olympic Games and the FIFA World Cup. Senegal is set to host the Youth Olympic Games in 2026, and preparations have already begun with the creation of the Olympic Forest. This forest is being planted in the future Olympic Village in Dakar [45]. In 2022, approximately 70,000 tree seedlings were planted for this occasion, marking the first phase of the tree-planting activities in both Senegal and Mali. The International Olympic Committee President and members marked this green initiative by planting a tree at the university campus of Diamniadio, which will be the future home of the athletes [45]. The planting of trees, during the National Tree Days, is a ceremony that brings with it a remarkable series of meanings for the organization of event, the participation of politicians, media, citizens, guests, and local populations. Also, the type of trees planted matter during this kind of ceremony.

3.3. The Large (Million Trees) Projects

- Five countries have been particularly active in announcing large projects: Ethiopia, Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana and Egypt. In 2019, Ethiopia announced a tree-planting initiative of 4 billion trees by the end of the rainy season, which was the second phase of the national Green Legacy Initiative. Ethiopia planted 25 billion trees during the first Green Legacy Initiative held between 2019-2022 involving the participation of more than 20 million people [46]. On July 29th, 2019, the Prime Minister (Abiy Jed), along with other government officials, NGO volunteers, and the population, planted over 350 million trees across the country within 12 hours. Then, on July 17th, 2023, the Prime Minister called on Ethiopians to surpass the previous year's tree-planting efforts and plant about 500 million trees in just one day, potentially setting a new world record. In a tweet the Prime Minister stated: "Our goal is to break our record!" Additionally, he tweeted, "Our competition is with ourselves. We believe that regions, zones, districts, and villages will surpass their own records by planting more than last year. Each of us has to break our own records." [47]. Nigeria follows Ethiopia in terms of the number of trees planted. The Nigerian president (Muhammadu Buhari) announced a massive reforestation plan for 25 million trees at UN Climate Action Summit in New York in September 2019. Since then, some states of the country, such as Lagos, have distinguished themselves with massive tree planting projects. While the national tree planting day in Nigeria is every 17th June of the year, the 14th of July of each year has been institutionalized and is observed annually as the Lagos State Tree Planting Day with planting of trees simultaneously at different locations across the State. For the Lagos government, 7.6 million trees were planted between 2011 and 2022. The former Nigerian President (Muhammadu Buhari) announcing a national reforestation project to plant 25 million trees calls the planting of trees a way to mobilize youth “We intend to mobilize the youth in the planting, breeding a sense of ownership of their region’s future and strengthening community bonds”, and an act against climate change within the country and region [48,49].In 2023, a massive tree planting project was announced in Kenya during the National Tree Day. The project was announced by the President of Kenya (William Ruto) to call on Kenyans to address climate change and deforestation affecting the country and to increase the country’s tree cover. He added by saying “If there is a programme that will make a meaningful impact in the attainment of our food security goals and address the cost of living, it is environmental protection” [50]. The goal is to plant 15 billion trees on 11 million hectares of land by 2030, which equates to planting at least four million trees each day [51]. In 2023 the President of Kenya also announced a public holiday on 13 November for a nationwide tree planting day, part of its plan to plant 15 billion trees by 2032 [52]. In 2022, Kenya aimed to hire 11,000 young people to cultivate 1.5 million trees in Nairobi's public spaces as part of the greening of the capital city initiative [53]. This effort builds upon previous tree planting campaigns, such as the one launched by former President (Uhuru Kenyatta) in 2018 at the Moi Forces Academy in Nairobi [54]. Kenya has a long history of celebrating National Tree Planting Day, which dates to 1971 when the first edition was launched by the country's first President (Jomo Kenyatta), who urged the nation to plant trees instead of burning them [55]. In Kenya, Wangarĩ Maathai that founded in 1977 the Green Belt Movement, a non-governmental organization promoting the planting of trees, in 2004 she became the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Ghana has been celebrating its National Tree Planting Day (Green Ghana Day) since 2021. The 2022 editions goal was to plant 20 million trees during the year, but over 26 million trees were planted, exceeding the target [56]. A total number of ten million seedlings were announced to be planted across the country for the 2023 edition of the Green Ghana Project. In 2022, the government of Egypt planted 3.1 million trees in the 27 governorates. The operation is part of the “100 million trees” initiative launched by Egyptian President (Al Sissi) on the sidelines of the 27th United Nations Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP27) held in November 2022 in Sharm el-Sheikh. “The Ministry of Environment has identified the types of trees that are planted in the 100 Million Trees Initiative, starting with being crops of economic return, whether fruitful trees such as olive, woody or other kinds of trees, in addition to determining the criteria for the types and sizes of trees that will be planted, as well as knowing the extent of their need for water, ease of irrigation and their ability to absorb pollutants from the air” [57].

3.4. National Days as a Symbol of National Unity and Patriotism

- There are cases where the planting of trees is directly associated with patriotic celebrations. We analyse briefly here the case of Niger, Burkina Faso and Rwanda. For example, in Niger, the national arbor day is celebrated on the same day of the country’s Independence Day.In Burkina Faso, since 2019, the National Tree Day edition was launched by the former President (Roch Kaboré) who encouraged the planting of trees in rural areas [58]. In 2020, the President presided the planting of 200 tree plants in the village of Siniena in the Cascades region. In 2023, after the recent coup d’états in the country, the current transition government used the planting of trees as a symbol of patriotism and unity. On July 15, 2023, Burkina Faso celebrated the 5th National Tree Day (Journée nationale de l'arbre) under the theme: “Tree, a symbol of community resilience in a context of insecurity.” During that day, around 60,000 native and non-native trees were planted as part of the national reforestation campaign which aimed to plant 5,000,000 tree plants across the country. The 43rd National Tree Day in Rwanda marked the beginning of the national tree campaign of 2018/19 which entailed planting millions of trees with a total of 44,589 hectares of land set to be covered with trees over the next six months. Special attention was given to Kigali and Eastern Province due to shortage of forest cover [59]. Tree planting efforts are part of the objective to achieve the target of covering 30 percent of the country with forests. In 2023 the tree planting season, organized by the Ministry of Environment together with several other government partners, was dedicated to increasing community involvement and ownership in landscape restoration for enhanced impact and sustainability. In 2023, Rwanda celebrated the International Day of Forest on the theme “Forests and Health”. In that occasion the Rwandan government in collaboration with its partners like the IUCN Rwanda, UN agencies, NGOs, Local Communities and Youth and Women communities planted over 8,150 trees on 3.5 ha in Gicumbi District and Bwisige Sector. It should be noted that Rwanda always celebrates the International Day of Forest with other two international days: the World Water Day and the Meteo Day, 22nd and 23rd of March respectively, as a way to emphasize on the importance of these days nationwide. In 2022, in Mali, the government encouraged the populations of Mande and the rest of Malians to plant trees against climate change and desertification [60]. The Prime Minister (Choguel Maiga) described the tree planting as an "act of faith and patriotism, given the degradation of natural resources and the effects of desertification in the country" [originally in French: {« c’est d’abord un acte de foi et un acte patriotique que de planter un arbre au Mali, au regard de la dégradation des ressources naturelles et des effets d’une désertification avancée qui caractérise notre pays »] [61]. Another example is Cote d’Ivoire where the Minister of Water and Forests marked his presence at the 26th edition of the National Peace Day whereby 140 trees were planted at Duekoue and many other cities of the country. During this 2022 event, the theme focused on the remembrance of forgiveness and boosting the common future of all Ivorians which was characterized by the tree planting activities [62]. This day was under the auspices of the Prime Minister (Patrick Achi) who participated in planting trees to symbolize peace and unity of the Ivorians [63]. Particular cases are those of countries that have been involved or are objects of armed conflicts. In the Central African Republic, the government and the President (Faustin-Archange Toaudera) used National Tree Day as an opportunity to call for national unity and peace. In Senegal, during the National Tree Day in 2023, the Senegalese Minister of Environment, Sustainable Development, and Ecological Transition celebrated this day under the theme: "one citizen, one tree for sustainable cities” [originally in French: “un citoyen, un arbre pour des villes durables’’] with the Caïlcédrat (Khaya senegalensis, or Khay in Wolof) as the main tree type promoted: “The caïlcedrat is one of Senegal's hallmarks. Alongside the lion, all the major arteries of our big cities were adorned with caïlcedrats.” [originally in French: "Le caïlcedrat est quelque part une des caractéristiques du Sénégal. A côté du lion, toutes les grandes artères de nos grandes villes étaient parées de caïlcedrats"] [64].

3.5. Announcements of Planting Trees for Sustainability to Protect Nature

- In several cases (e.g. Cote d’Ivoire, Seychelles), National Tree Days are often announced as one of the main means to protect the environment, fight climate change, and protect biodiversity. In Cote d’Ivoire the National Tree Day was launched by the first Ivorian President (Houphouët-Boigny) in 1983 on the 5th of July. The purpose of this day is “to encourage Ivorian population, to develop love and respect for nature, and for flora and fauna” [65].Every 15th November of the year, the country also celebrates the National Day of Peace and trees are planted nationwide. In 2019, the Ivorian government organized a planting operation of a million trees throughout the country under the theme: "One Day, One Million Trees campaign". The Minister of Water and Forests stressed the importance of planting trees in the country and especially in cities like Abidjan where about 400,000 trees were planned to be planted. In 2021, the Minister of Water and Forests took part, on October 29, in Abidjan in the Anguededou Classified Forest, in the National Day "1 day, 50 million trees", aimed at restoring Ivory Coast's forests cover. According to the minister, no development action, or even no form of life, can prosper on earth without the ecosystem services generously offered by trees and forests [66]. The partial assessment to date indicates that 28,538,234 trees have been produced and planted, i.e., an achievement rate of 57.08% [67]. A project to rehabilitate watersheds and catchment areas by planting 4,000 trees native to Seychelles was planned in 2018. The overall aim of the project is for adaptation to climate change. The project was funded by the Adaptation Fund. On the 29th of March 2023 (National Tree Day), every Seychellois citizen was invited to plant a breadfruit tree in their garden [68]. During a national day dedicated to breadfruit planting, the Minister of Environment and other government officials set the example by planting breadfruit trees. On the main island of Mahé there were just over 4,000 trees two years ago, their number has more than doubled in March 2023 with 9,000 trees recorded. Other islands, that have no national tree days but have publicly declared trees planting activities include the Comoros, Mauritius and Madagascar where for example on the 60th anniversary of independence on June 26, 2020, the President (Andry Rajoelina) announced the planting of 60 million trees in one year [69]. In the Comoros in 2022, for example a campaign with the UNDP support was launched to plant 613,000 new trees on 571 hectares of land throughout the country.Countries that have no celebrations of national trees days have nevertheless activities related to trees. In Gabon, on January 2020, the Minister of Water and Forests officially announced that the government is planning to plant 200,000 hectares of trees to enhance the contribution of the forest sector to GDP over the next 5 years (2020-2025). The main aim of planting these trees is to increase its economy to 3000 billion FCFA in 2025, against 500 billion FCFA in 2019 and 300 billion FCFA in 2018. Currently, the contribution of the Ministry of Water and Forests represents about 5% of Gabon's gross domestic product. Also, this tree project is aimed at fighting climate change through carbon sequestration [70]. In January 2022, Gabon plans to plant 200,000 hectares of fast-growing trees by 2025 to support the development of the timber industry in the specialized economic zones of Franceville and the peri-urban area of Lambaréné [70].

4. Discussion

4.1. The Changing African Landscape and Planning Policies of Planting Trees

- Although there is the proclamation of planting seeds and reforestation initiatives, “deforestation persists in Africa because conservation policies and projects consistently ignore the fact that conservation is possible only under limited, specific conditions. These conditions relate to the concurrent alignment of key actors’ interests at two critical levels of decision-making: local and national” [71] (p.3). Just to give an example, in Cote d’Ivoire satellite images analysis indicated “a change and a conversion of forestlands into agriculture from 1987 to 2015 at a rate of 1.44%/year and 3.44%/year for dense forests and degraded forests, respectively” [72] (p.1). And the “major causes of deforestation perceived by farmers included population growth (79.3%), extensive agriculture (72.9%), migration (54.2%) and logging (47.7%)” [72] (p.1).National policies to enforce and manage trees planting projects are few and not mentioned in most of the identified projects, except for policies implemented to comply with international agreements (e.g. Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement). A range of different types of green spaces exist in Africa, but much emphasis is given to planting urban trees [3]. Climate action and the well-being of the population are announced outcomes from these tree activities however, sometimes, tree-planting activities are used for political propaganda [4]. Most of these projects' impacts are expected and difficult to measure as actual outcomes. Official monitoring and evaluation teams have rarely been established, and reports are scarcely available [73]. Much information is available from Presidents’or Ministers’announcements during international summits or national events like the National Arbor Days but afterward no tracking policies are implemented or envisaged for the effectiveness of these projects. And tracking mechanisms of tree projects in rural areas are lesser than in urban areas [74]. This has clear consequences on the risk for many tree seedlings planted that are not nurtured and die. For example, we know that in Malawi, it has been reported a poor survival rate of trees planted by government during the Forestry season (Malawi Institute of Journalism, 2024) [75]. The loss is due to several factors, for example late tree-planting, ignorance on ecological requirements, livestock grazing, bush fires but in particular the need for more than 97% of the population of wood for cooking and heating [74].Overall, there are several points of discussion, mostly related to the way planning has developed. Urban and landscape design has taken a prominent role in planning, although more strategic planning, in a sustained forced urbanization pattern, should and could play an important role in human health, while peri-urban and rural areas are neglected. Globally, it was estimated that “there has been the conversion of nearly 125 000 km2 of cultivated or with natural vegetation land [similar size of Malawi or Greece or half size of the UK] to urban land uses” [76] (p.8). In West Africa, in the period between 2003 and 2019, the land dedicated to agriculture reduced by −1.4%, while the built-up area increased by 25.8% [77]. In East Africa, analysis reported a 34.8% increase in the area of cropland converted mostly from open grasslands, wooded grasslands, and open forests [78]. Traditional planning practices adopted in the Global North present significant limits for cities in global south regions [79]. Because of an extended list of issues, rural areas in global south regions are far away from the traditional planning vision of the Global North. The main issues that emerged from the various projects in rural Africa promised, active, or of unknown status is still a deep colonial and Eurocentric perspective [80]. If urban planning needs a paradigmatic change when addressing African cities, this is even more needed for the peri-urban and rural areas. One notion is important to consider, the notion of ‘borrowed urbanisms’, of ‘worlding’ used to examine how cities of the global South have been ‘worlded’ in the discourses and imaginaries of urban studies [81]. This notion can be extended to peri-urban and rural African areas that are considered an isotropic land that can accommodate the same planning examples from Europe or the USA. In reality, rural African areas reproduce racialized landscapes transformed by “initiatives —which also contain positive elements— […] embedded in asymmetric power relations rooted in the colonial past and in discourses and assumptions that are coined by Northern epistemologies and ontologies” [80] (p.13). If we consider the notion of “conflicting rationalities” we see how African societies are shaped by deep conflicts [81]. These conflicts are the background of planning, that can hardly work with importing standard solutions, visions and “best practices and examples” from the Global North. Particularly new approaches, and addressing new questions, are needed in the presence of global and local competing perspectives. If we do not consider the social and cultural background, we cannot comprehend why there is a huge challenge in projects aimed at planting trees. Countries with predominant arid climate, such as Ethiopia, Egypt and Senegal have embarked in greening rural areas and cities, but the announcements are similar to countries in the tropical zone, just in terms of big numbers declared. Planting trees in rural areas in Africa seems to be a “surprising” initiative as the population in many villages has been used to living adapted to the natural environment [82]. People know that trees are a vital resource for them, by providing a valuable source of food and nutrition, offering shade and shelter, helping to prevent soil erosion, granting cultural connections and also providing income [83]. What motivates the planting of trees is a set of different overlapping and contradictory reasons. The most apparent one is that the reason given for planting trees comes from increasing desertification due to climate change and biodiversity loss, soil leaching and tree cover loss due to unconventional practices like bush fallowing, and monoculture. But the mechanisms set up to combat deforestation are not efficient [84]. Deforestation is not happening by chance and local communities often excluded from decision-making have traditionally been able to preserve forests [85]. And the recurrent announcements of tree planting happen within a huge trend of rural-urban migration as a consequence of environmental degradation, lack of services and disparity of opportunities between rural and urban areas, violent conflicts and wars. Deforestation and degradation of forest landscape continue at an increasing rate in Africa due to the ambiguous environment created by governments to regulate land tenure security for interested stakeholders [86].Tree planting can be an important way to mitigate the effects of climate change. African countries have primarily been passive beneficiaries of voluntary carbon markets depending on international demand [87]. Carbon offsets rarely achieve the climate benefits they claim and are primarily used to justify ongoing emissions, rather than reduce them [88]. And a singular focus on the carbon sequestration potential of projects fails to account for other fundamental benefits provided by trees for ecology, health and social activities.

4.2. The First Layer of Analysis of the Projects of Planting Trees in Rural Africa

- At a superficial level of analysis, we see that the picture, with related obvious suggestions, for planning that emerge is:- There are no regular reports provided by responsible agencies and the governments, while this should be the rule.- Efforts to green rural and peri-urban areas are often one day or temporary events, while they should be a coordinated effort of governments, non-governmental organizations and local community.- National projects are usually launched in capital cities and later nationwide and this emphasis should be addressed to avoid the socioenvironmental injustice and discrimination between people of cities and villages. - Social and health outcomes of tree planting projects are not considered, while the expected social and health outcomes of these projects should really consider the expected wellbeing of the populations.- Health consideration, air pollution, and water impacts are not included in all trees’ projects before executed, while this should be done. - Many African governments are relying heavily on funds from international donors and partners, while they should take into consideration greening spaces projects into their yearly budget. Nevertheless, these set of suggestions ignore another layer of political implications for planning that we discuss in the next section.

4.3. The second Layer of Analysis: Implications for Landscape Planning, Design, Management, and Policy

- If we explore deeper the situation of the planting trees projects, we have to highlight a new set of critical points. We can identify a first set of points that are related to best practices for planning.Firstly, the planting of trees should be part of a large effort to see planning in a wide and integrated way. The integration should consider at least three aspects: the different parts of the territory, social economic and well-being aspects, feasibility and constraints including all historical and cultural aspects. Tree planting projects in rural Africa in the period investigated (2012-2023) are huge in terms of promises and they have a relevant role in some cases and a somehow peripheral role in other cases within the agenda of African governments compared to the planting trees projects in urban areas. Many tree-planting projects in rural Africa were launched during national reforestation campaigns and national tree days, but they were announced in the nations’ capitals (urban areas) even though a good number of trees were planted in villages, peri-urban and rural areas. Because of their involvement in huge reforestation projects, overall rural areas tend to receive more planted trees than urban areas. We have the puzzle that national authorities pay no attention to trends that are affecting their territory and with transnational actors they embark on bringing nature back to the cities that are growing without any planning [89]. For example, the “Green Ethiopian Legacy Initiative” launched by the Ethiopian Prime Minister announced a tree-planting initiative of 40 billion trees starting in 2019 [90]. On the 29th of July 2019, the Prime Minister presided over the tree planting kick-off whereby 350 million trees were planted in the whole country within 12 hours starting from Addis Ababa. This tree-planting campaign received a lot of media attention and inspired other countries like Botswana to copy the example [91]. In a nationwide effort, Forest Conservation Botswana is launching a mass tree-planting campaign called Trees for Life. The goal is to plant 10,000 trees (budget of 100,000 USD). This initiative aims to plant more trees in rural areas than in urban areas, but media attention was placed on urban forestry [91]. In general, large-scale interventions, e.g. billion trees projects, have an important role to define long-term objectives and they can symbolically trigger and promote other small-scale projects, but their colossal character makes them fragile and successful only along decades, with mixed and contrasting evidence from short and medium-term monitoring about their results in arid and semi-arid areas for water and irrigation needs [92-95]. According to data collected on the involvement of children in schools in South Africa, it was found that most urban schools had participated in Arbor Week activities (tree-planting, displaying posters, and having speeches). In contrast, one-fifth of rural schools had never participated in any way [96].The economic aspect often involves integrating into two different areas: local production and tourism. However, the idea of planting trees in rural Africa to support families by growing edible trees (fruit trees) for nutrition is not frequently included in plans. Eco-tourism could have a positive effect when tree projects are encouraged in rural areas but there are many limitations to the generation of potential benefits [97]. Health and well-being of the populations should be considered as well as elements of economic developments that is ignored in most of the cases. Health and well-being mean the capacity to see the whole spectrum of benefits coming from planting trees, green spaces and nature protection [98], in an integrated and holistic way, for example considering the One health approach [99]. Gender unbalanced coordination of projects is clear, for example in the AFR100 initiative there are only two women out of thirty-four focal points. We face reductionist definitions based solely on the presence of trees, disregarding the fact that rural areas and forests are a habitat for different ecosystems, as well as the home of local communities. Trees plantation cannot be done in a haphazard manner as it can limit other land-use patterns and activities relevant for sustainable livelihoods [100]. Also, trees plantation implies many negative effects such as soil acidification and a decrease in soil fertility in the long-term as nutrients are highly demanded from afforestation [92].Declarations and announcements represent a way to produce and reproduce dominant discourses on the environment and they are useful for further analysis [100]. We face a hegemonic top-bottom approach, very often paternalistic, that leaves very few spaces for participatory planning and its eventual success, but de facto mirroring and legitimizing authoritarian interventions against local populations [102]. A pattern of limited relations with local populations established by colonialism has survived in many African countries. Most of the projects have basic conceptualizations that limit their development. For example, anthropocentrism looks like the only approach to planting trees, accompanied by the promotion of a binary view of nature/society where non-humans are absent [99]. Overcoming these conceptualizations of reality is difficult and there is the need to engaging on the colonial and post-colonial discourses, as well as committing with indigenous knowledge. New questions for planners should be considered when addressing territories where there are open conflicts and clear interests of those concerned only with exploiting and plundering natural resources. Some questions are very urgent: how do indigenous peoples can speak about their planning vision? [104]. Which norms to adopt? [79,105]. Is planning trees, with their “miraculous” power to recover and improve the environment, a way to depoliticize and collapse the existing divergences and conflicts between groups that would struggle over land use, forest issues, unequal access to resources and the way to resist to predatory relations? How peculiar are the projects to be implemented in war and post-war zones?

4.4. Limitations of Our Analysis

- The limitations of our analysis are related to the sparse availability of official online data in many African countries and the need to rely on media sources that have their own limitations. We also had not much information, neither the time, to assess the effectiveness of the interventions selected and collected. The limitations of our study indicate several research gaps for future studies on tracking political announcements and their follow-up in specific countries where information is lacking or non-transparent, attempting an assessment of their effectiveness, and additionally there is the need to deal with the questions that we have posed at the end of the previous section. Those questions do not have final answers to be given, but they are an invitation to a critical engagement of scholars on the vast political implications of the “let’s plant trees” messages, policies and interventions. Another relevant research topic, that was out of the scope of this paper, is the quantitative assessment of environmental policies. The quantitative assessment of environmental policies that promote the planting of trees requires trees inventory, trees growth model, and a choice of indicators to be measured (e.g. height, diameter, crown transparency, etc.). Although not usually carried out in Africa, this kind of quantitative assessment is well-established and makes use of the improvement in methods and technology, for example using satellite data [106].

5. Conclusions

- This paper aimed to explore the effects of tree-planting initiatives in rural and peri-urban Africa, focusing on the types of projects planned during National Tree Days, the key stakeholders involved in these initiatives, and the implications for environmental planning. In relation to our analysis there is to consider the more complicated issue of the decision-making and tracking process that is part of serious planting trees projects or events. In this case there is the need not only of analysis that have to take into account a wide variety of information but also of participatory processes that are difficult to implement. The case of planning these activities in lands where indigenous communities live is one where often violence and power relations establish the indicators for the decision and “success” of projects. The main-stream methods that evaluate ecosystem services and social benefits include multi-criteria decision analysis, geospatial technologies, participatory engagement of lay persons in the decision process and many other techniques. But the issue we just mention is that there a conceptual gap between the way of planning built in Europe and North America and the way indigenous peoples conceive planning.The analysis of National Tree Days across 54 African countries and several projects under-scores mixed trends and directions observed. On one hand, there is a growing awareness and willingness to tackle environmental challenges. On the other hand, submission to an international agenda and the challenging political and social conditions of many countries poses significant obstacles. Between 1990 and 2030 the number of tree planting organizations have increased by 288%, especially for-profit organizations [37]. The initial recommendation for policy makers and government officials is to prioritize tree-planting projects in rural and peri-urban areas of Africa, similar to those undertaken in urban regions. Tree planting activities should not only be launched in villages for political and election reasons. The health and well-being perspective and socioenvironmental conditions of the local population should be improved and considered when executing such projects. In agreement with several scholars, it is important to stress the fact that the announcement of projects and initiatives should be on the benefits as well as tree diversity and tree equity and not on the number of trees planted. Tree projects in villages and cities should be done simultaneously and coherently to have fruitful results during National Tree Days.If we move to another level of analysis and consider some implications for planning the results are different and difficult interpretation, although some features are dominant. All the trees’ announcements indicate to us which way nature is simplified and defined, and the nature-society relation is built, in particular on the difficulties of defining a non-binary but more complex and adequate relation between humans and the environment. The difficulty of separating the two is increasingly being challenged by scientists, for example anthropologists, but not from planners and developers still anchored to narrow visions. After all the analysis of the data collected, we remain with a difficult question: is it possible to conceptualize and transform trees planting activities in emancipatory projects for Africa? Planting trees should not only be considered a significant policy to deal with the current global trends in climate change but also an effective way to build sustainable and ecological societies that do not exploit and destroy their environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Future Green City World Congress in Utrecht in September 2024 and at the 2nd African Forum on Urban Forests in Johannesburg in March 2025. We also thank all the anonymous reviewers that have provided useful comments. This paper reflects the authors’ views. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication, and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the WHO.

References

Annex

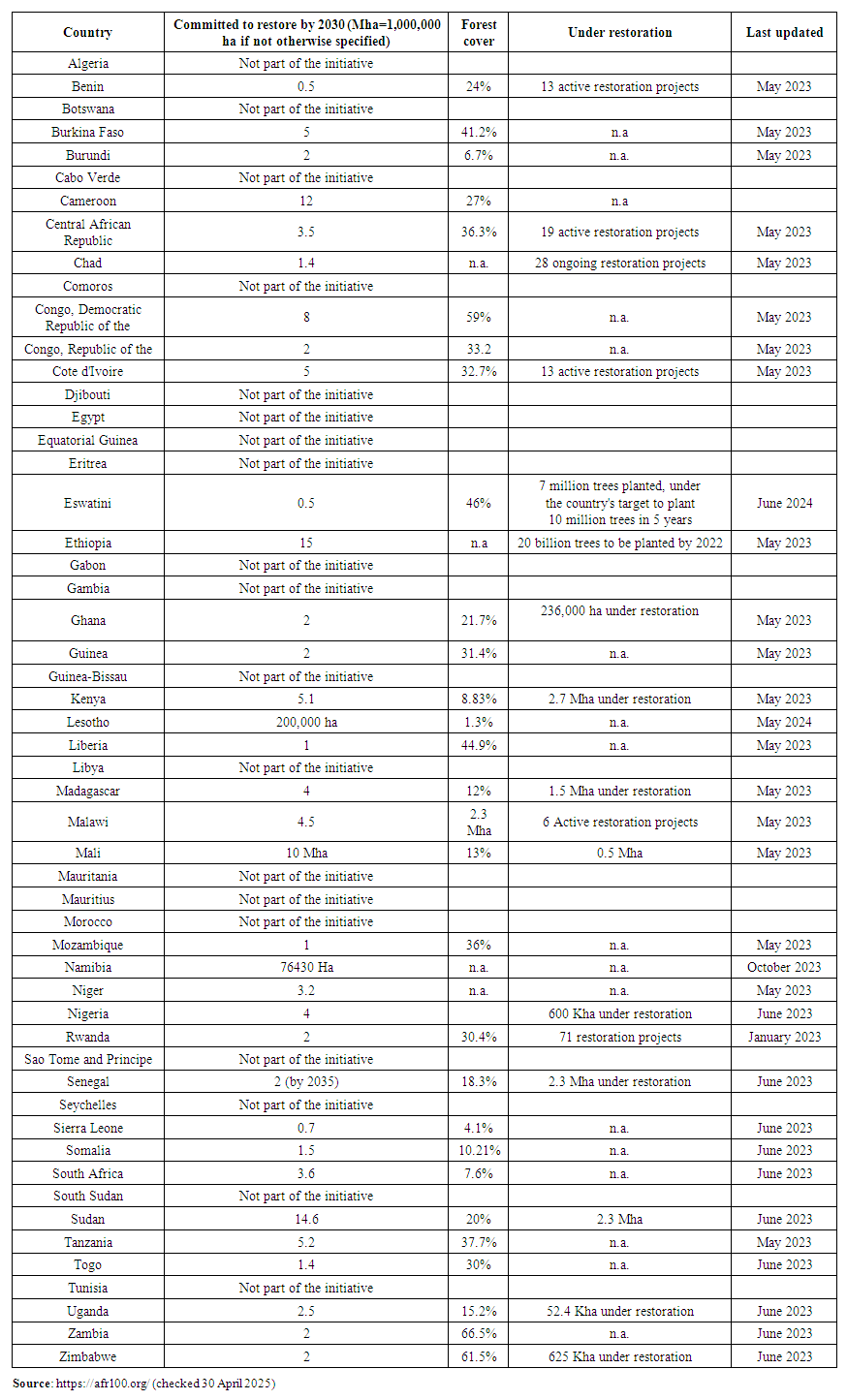

- 1. Additional Details on Materials and MethodsIn this article, an overview of the existing tree planting initiatives is provided related to "tree days" in Africa, particularly in rural areas. The analysis along the year 2023, gathered data on tree-planting policies in Africa from a diverse array of sources. The Table S1 is one of the first attempts, to our knowledge, to build a dataset of the National Tree Days in Africa, their date of proclamation and justification, if available, plus some additional information. To compile the information, firstly official website of governments and international agencies (FAO, UNDP) were checked and if no information was available other sources, for example news media, NGOs and social media were used. General searches using the terms such as "planting trees," "plant trees," "National Tree Day," "Africa," and the English name of the country. In addition, searches were conducted in French using "plantation d'arbres," "planter des arbres," and the French name of the country, as well as in Portuguese using "plantação de árvores," "plantar árvores," and the Portuguese name of the country were carried out in Google. The majority of the data comes from official documents, national project reports, media reports, United Nations reports, scientific literature, media reports, and international development agencies, as well as non-governmental organizations. In many cases, data were verified by accessing information from multiple sources. In summary, the different sources include national reports, regional documents, international reports, official websites, United Nations agencies reports, and information retrieved from international development agencies and non-governmental organizations, as well as worldwide news channels, and Government websites. It is important to note that these sources were utilized to construct this database. For each country, the database has three main components, including the month and day of the first year of proclamation of the National tree day (or the first date we have the news that a national tree day was celebrated), and the legal justification if available. One of the significant challenges in collecting data is that many African governments do not publish much information or reports online about their tree planting projects. However, data can be found from various sources such as newspapers' websites, NGOs' webpages, and a few Ministry pages or social media posts and other various sources. FAO provides a relevant resource of information,1 and the FAOLEX database provides useful information on laws and decrees that were adopted by countries. In this research Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning were not used in any form, neither for the automated extraction of information from websites, databases nor in content generation. But updates and refinement of this work can benefit from the use of new technologies in automating a large variety of manual processes needed to retrieve data, provided that a validation process on consistent generation of data is in place.The Table S2 is the summary of the interim targets calculated based on proportionate land sizes and established for each of the countries towards the 2030 goals of the Great Green Wall Initiative. In 2007, the African Union launched the Great Green Wall (GGW) Initiative across 11 countries: Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti. This initiative is currently led by the Pan-African Agency for the Great Green Wall (PAGGW).2 In 2021, the GGW Accelerator proposed a new framework to monitor the progress of this program in collaboration with the PAGGW. The mobilization of appropriate tools for implementation is essential for tracking and achieving the goals of the GGW, which aims to restore 100 million hectares of land, create 10 million jobs, and sequester 250 million tons of CO2 equivalent emissions.3The Table S3 describes the AFR100 commitments and progress.

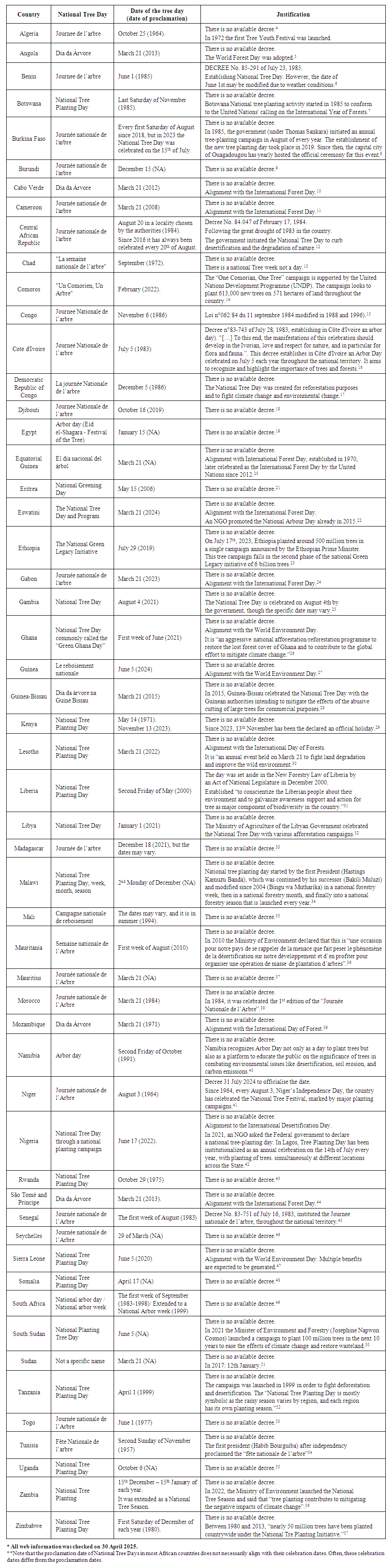

| Table S1. National Tree Days in Africa (National Tree Day & Date of Proclamation) |

| Table S2. Great Green Wall targets by country |

| Table S3. AFR100 commitments and progress by country |

Notes

- 1. FAO: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1479759/ 2. UNCCD: https://www.unccd.int/news-stories/statements/new-observatory-track-progress-africas-great-green-wall 3. Great Green Wall: https://thegreatgreenwall.org/ggwamp 4. On the date of 25 of October see: https://and.dz/site/wp-content/uploads/Décret-exécutif-n°-09-101.pdf. Stamps were issued in 1964 to celebrate the Tree Day.5. Embaixada da Republica de Angola em Portugal: http://www.embaixadadeangola.pt/angola-celebra-dia-mundial-das-florestas-com-plantacao-de-arvores/ 6. FAO: https://www.informea.org/fr/legislation/d%C3%A9cret-n%C2%B0-85-291-du-23-juillet-1985-portant-institution-de-la-journ%C3%A9e-nationale-de-l 7. Daily News: https://dailynews.gov.bw/news-detail/6985 8. French.XINHUANET: https://french.xinhuanet.com/2018-07/25/c_137347957.htm 9. Biodiversité du Burundi: https://bi.chm-cbd.net/fr/taxonomy/term/1480 10. Governo de Cabo Verde: https://www.governo.cv/mdr-comemora-o-dia-mundial-da-agricultura-floresta-agua-e-da-meteorologia/ 11. Republic du Cameroon: https://www.minesup.gov.cm/index.php/2023/03/21/ and Cameroon Tribune: https://www.cameroon-tribune.cm/article.html/56063/fr.html/journee-internationale-de-larbre-les-jeunes-appeles-la-reforestation 12. Page officielle de la Primature en République Centrafricaine: https://www.facebook.com/primaturercaofficiel/posts/439278361575585/?_rdr 13. Le Pays: https://www.lepaystchad.com/941/ 14. UNDP: https://www.undp.org/fr/africa/histoires/un-comorien-un-arbre-le-gouvernement-de-lunion-des-comores- et-le-pnud-lancent-une-initiative-de-reboisement-ambitieuse-avec-le 15. République du Congo: https://www.assemblee-nationale.cg/2024/11/11/38eme-journee-nationale-de-larbre-lassemblee-nationale- fortement-mobilisee-autr/ and République du Congo: https://liziba.cg/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Decret-n%C2%B088-617-1988-Journee-nationale-de- l_arbre.pdf 16. FAO: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC154632/ 17. Democratic Republic of Congo: https://peuplesautochtones.cd/events/journee-nationale-de-larbre-le-projet-dappui-aux-communautes- dependantes-de-la-foret-en-rdc-contribue-a-lutter-contre-la-deforestation-par-la-plantation-darbres/ 18. Facebook page of a school: https://www.facebook.com/100063776536441/posts/102260131198885/ 19. Commercial website of HolidaySmart: https://www.holidaysmart.com/calendar/arbor-day/egypt 20. FAO: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1479759/ 21. Eritrea – Ministry of Information: https://shabait.com/2019/05/18/national-greening-campaign-day-remembered/ 22. Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xv7z_N9lVKU and Guba NGO: https://www.gubaswaziland.org/community-projects/tree-planting/ and https://entc.org.sz/environmental-days/#1653880123872-4b844b2a-bf42 23. UNEP: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/ethiopia-plants-over-350-million-trees-day-setting-new-world-record 24. Republique Gabonaise - Ministere des Eaux et Forets: https://www.eaux-forets.gouv.ga/879-communique-de-presse-2023/9-le-ministre-recu-par-le-president- de-la-transition/520-promouvoir-des-villes-vertes-au-gabon/ 25. The Point newspaper: https://thepoint.gm/africa/gambia/headlines/environment-minister-launches-2021-national-tree-planting-day 26. Ministry of lands and natural resources of Ghana: https://greenghana.mlnr.gov.gh/ and Miistry of Tourism, Culture & Creative Arts of Ghana: https://greenghana.mlnr.gov.gh/ and GhanaWeb: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/features/A-call-for-a-National-Tree-Planting-Day-and- a-man-s-journey-to-plant-20-million-trees-in-Ghana-739320 27. Emergence magazine: https://emergencegn.net/la-guinee-celebre-la-journee-internationale-de-la-foret-sengage-a-proteger- davantage-ses-ressources-forestieres/ 28. RFI: https://www.rfi.fr/br/africa/20150701-guine-bissau-assinala-dia-nacional-da-arvore 29. REUTERS: https://www.britishpathe.com/asset/112509/ and The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/07/kenya-makes-13-november-nationwide-tree- planting-day-a-public-holiday and Kenya Biodiversity - National Clearing House Mechanism: https://ke.chm-cbd.net/photo-galleries/kenya-makes-13-november-nationwide-tree-planting-day -public-holiday 30. Standard Lesotho Bank: https://www.standardlesothobank.co.ls/lesotho/personal/About-us/press-releases/standard-lesotho-bank -and-ministry-of-forestry-roll-out-nationwide-tree-planting-to-commemorate-the-international-day-of- forests and Government of Lesotho: https://www.gov.ls/pm-leads-national-tree-planting/31. AllAfrica: https://allafrica.com/stories/200605081091.html and Robert Santi’s facebook: https://www.facebook.com/100054396362743/posts/1166134128543122/?_rdr32. Lybian Cloud News Agency: https://en.libyan-cna.net/life-and-community/the-libyan-government-celebrated-the-national-tree-day/ 33. 2424mg: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F36RIToMBDY and https://midi-madagasikara.mg/journee-de-larbre-graine-de-vie-en-action-dans-4-regions-du-pays/ 34. Gregory Gondwe blog: https://gregorygondwe.wordpress.com/2010/03/29/planting-65-million-seedlings-to-stop-deforestation/. Stamps were issued in 1979 to celebrate the Tree Day.35. UNESCO: https://www.unesco.org/fr/articles/lancement-de-la-29eme-edition-de-la-campagne-annuelle-de- reboisement-au-mali 36. Government of Mauritania: http://www.environnement.gov.mr/fr/index.php/accueil/actualite/409-lancement-de-la-semaine-nationale -de-l-arbre-un-mauritanien-un-arbre# 37. lexpress.mu: https://lexpress.mu/s/article/302751/journee-internationale-forets-vers-un-reboisement-maurice 38. Jeuneafrique: https://www.jeuneafrique.com/143561/societe/le-maroc-c-l-bre-la-25-me-journ-e-nationale-de-l-arbre/ 39. Ministério da Terra e Ambiente - Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MTAmbiente/posts/mo%C3%A7ambique-celebra-o-dia-internacional- das-florestas-conservando-e-plantando-mai/2893028730974287/ and Rádio Moçambique: https://www.rm.co.mz/pais-comemora-se-hoje-o-dia-internacional-das-florestas/ and IIAM: https://iiam.gov.mz/index.php/2024/03/21/pelo-dia-das-florestasplantar-uma-arvore-e- contribuir-para-a-proteccao-da-biodiversidadepelo-dia-das-florestas/40. AnydayGuide: https://dayhist.com/holidays-and-occasions/arbor-day-namibia 41. Government of Niger: https://hydraulique.gouv.ne/index.php/actualites/80-celebration-de-journee-nationale-de-l- arbre-premiere-edition#: and: https://hydraulique.gouv.ne/index.php/actualites/80-celebration-de-journee-nationale-de-l- arbre-premiere-edition#:42. Punch: https://punchng.com/declare-national-tree-planting-day-group-urges-fg/ and Voice of Nigeria: https://von.gov.ng/2022-tree-planting-campaign-begins-in-nigeria/ and Lagos State Parks & Gardens Agency: https://lasparkportal.lagosstate.gov.ng/lagos-state-tree-planting-day-2024-nurture-our-future/ 43. The Forefront Magazine: https://theforefrontmagazine.com/community-work-umuganda-activities-focused-on-national- tree-planting-day-in-rwanda/ 44. FAO: https://www.fao.org/sao-tome-e-principe/noticias/detail-events/es/c/1480617/ 45. VivAfrrik: https://www.vivafrik.com/2019/08/05/journee-nationale-de-larbre-au-senegal-place-de-larbre- dans-les-planifications-strategiques-a32581.html 46. franceinfo: https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/mayotte/les-seychellois-sont-appeles-a-planter-des-arbres-a-pain-1379938.html 47. UNDP: https://www.undp.org/sierra-leone/news/world-environment-day-2020-launch-national-tree-planting -address-climate-change-and-national-development 48. Government of Somalia: https://molfr.so/event/happy-somalia-national-tree-planting-day/ and FAO: https://www.fao.org/somalia/news/detail-events/en/c/247645/49. South Africa - Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment: https://www.dffe.gov.za/launch-arbor-month-campaign-2022-0#:~:text=The%20idea%20is%20to %20highlight,annually%20from%201%2D30%20September. 50. Anadolu Agency: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/south-sudan-launches-100m-tree-planting-campaign/2277721#: 51. Sudan News Agency: https://suna-sd.net/posts/Sudan-Celebrates-International-Day-of-Forests%C2%A0 52. AnydayGuide: https://anydayguide.com/calendar/1694 53. Togo - Ministère de la Sécurité et de la Protection Civile: https://securite.gouv.tg/la-journee-de-larbre/ 54. La Presse.TN: https://lapresse.tn/2023/11/19/la-fete-de-larbre-2023-une-annee-pas-comme-les-autres/ 55. The Independent: https://www.independent.co.ug/roots-campaign-surpasses-one-million-trees-planted-during-this- years-national-tree-planting-day/ 56. Diggers news: https://diggers.news/local/2022/12/15/govt-launches-2022-2023-tree-planting-season/ 57. The Herald: https://www.herald.co.zw/tree-planting-alone-is-not-enough/ and Zimbabwe Forestry Online: https://www.zimbabweforestrymagazine.com/article/zimbabwe-commemorates-national-tree-planting-day/. A stamp was issued in 1981 to celebrate the National Tree Day.58. https://ggw-dashboard.dgstg.org/en/methodology/

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML