-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Ecosystem

p-ISSN: 2165-8889 e-ISSN: 2165-8919

2024; 13(1): 20-29

doi:10.5923/j.ije.20241301.02

Received: Sep. 6, 2024; Accepted: Oct. 2, 2024; Published: Oct. 31, 2024

Effects of Seasonal Fires and Occurrence on Tree Species Density Across Fire Treatment in Makambu, Kavango West Region, Namibia

Eva Kasinda1, Francisco Moreira2, José Eugênio Côrtes Figueira3, Lucas Rutina1, Ezequiel Fabiano1

1Faculty of Agriculture, Engineering and Natural Sciences, University of Namibia, Namibia

2CIBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Campus de Vairão, Universidade do Porto, Portugal

3Laboratório de Ecologia de Populações, sala B2 170, Depto. de Genética, Ecologia e Evolução, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas / UFMG, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brasil

Correspondence to: Eva Kasinda, Faculty of Agriculture, Engineering and Natural Sciences, University of Namibia, Namibia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The effect of fire regimes on tree density remains a subject of research particularly in Namibia. Fire regulates the composition and structure of many terrestrial ecosystems. Uncontrolled fire can negatively affect the functioning of ecosystems including carbon dynamics. Fire is now considered a threat to biodiversity. We analysed the effect of the seasonal and occurrence of fire on tree density in the Kavango West Region, Namibia. Specifically, this paper investigated the effects of fire season and occurrence, on tree density across four treatments. The quantitative study followed a completely randomized block design consisting of four fire regimes (March/April, June/July, and October/November) and a control. For the study revealed that densities of trees differ significantly between the three burning seasons (late wet season, dry season, and late dry season) One-Way ANOVA (F= 180.488; df = 2; p= 0.000 (P-value<0.05). There was no significant difference observed on the effect of fire season on species specific tree densities, a Kruskal-Wallis (H test) revealed (H(Chi2 > 0.05); Hc(tie corrected > 0.05); P-value > 0.05). For the effects of fire occurrence on tree density of different species a One-Way ANOVA showed a significant difference between the burnt and unburnt plots (F=290.712, df=1, p-value=0,000 (P<0.05). At the species level, no significant differences were observed in the average density of (b, d-h, j-l) between the burnt and unburnt plots (Mann-Whitney (U) test, p-value>0,05). Except for, average densities, for Baphia massaiensis were significantly higher in unburnt areas than burnt (F= 7.317, total df=18, p-value =0.015) and Croton gratissimus (F= 8.476, and total df=18, p-value =0.010) which was also significantly higher in unburnt areas than burnt plots. This suggests that there are no major effects of fire on tree density. Therefore, for Woodland management purposes the ministry can choose either burning because the burning has no effects on tree density within the context of our study area. Further studies on the effect of different fire regimes on soil or macroinvertebrates are recommended.

Keywords: Fire, Tree density, Fire occurrence, Fire season, Makambu and Kavango West Region

Cite this paper: Eva Kasinda, Francisco Moreira, José Eugênio Côrtes Figueira, Lucas Rutina, Ezequiel Fabiano, Effects of Seasonal Fires and Occurrence on Tree Species Density Across Fire Treatment in Makambu, Kavango West Region, Namibia, International Journal of Ecosystem, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2024, pp. 20-29. doi: 10.5923/j.ije.20241301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Fire regulates the composition and structure of many terrestrial ecosystems, changing them from one state to another [1]. Anthropogenic fires have been reported for the last 10,000 years [2] and are used as a management tool to preserve biological integrity and aid the functions of many ecosystems [3-5]. Fire is frequently acknowledged as the principal moderator of savanna dynamics, structure, and function [6]. According to research by [3-5], and others, fire is known to kill, damage, and destroy unprotected plant tissues. Fire occurrence can result in tree mortality and a subsequent decrease in density. This effect may be especially noticeable in species with limited fire adaptations or fire-sensitive species. In turn, the death of a tree caused by fire reduces competition for soil nutrients among survival plants allowing vegetation to change over time through differential recruitment and survival of seedlings and saplings [7]. Fire season, which is affected by the rainy season, involves the fuel moisture content, which in turn is key factor influencing fire intensity [5]. In their results, it was observed that a range of fire intensity occurred in all seasons, but low-intensity fire predominates in summer and autumn. Higher fuel moisture results in lower combustion and consumption rates and lower rates of fire spread [5]. Other effects of fire season are related to the vegetation's physiological (and phenological) status according to [8], which varies across seasons. This is another factor to expect differential effects on trees potentially. Fire intensity is related to both the seasonality and frequency of burning since it depends on the type and load of fuel [9]. The fuel load and fire intensity increase with the length of time between flames. Various fire intensities have various effects on plant and propagule survival. Fire intensity also variously affects each species' physical and biological environments, making conditions sometimes more, sometimes less, suitable for establishment and growth. Ecosystems with frequent fires suffer considerable changes in vegetation composition between fires [10]. Woody vegetation may be reduced in size due to repeated flames, but they seldom die, and larger individuals are frequently resistant to life-threatening fire damage [6,11]. Most plants become fire-resistant because of current fires [6,10,12]. This study seeks to contribute to understanding how fire occurrence, season, and intensity affect vegetation density by comparing burned and unburned (fire occurrence) and assessing the effect of fire season ((F1) Mar/Apr, (F3) Jun/Jul, and (F4) Oct/Nov)). There are a lot of studies conducted on fire in Namibia such as a study by [13] explored frequency, fire seasonality, and fire intensity within the Okavango region (when East and West was one region) derived based on MODIS fire products, [14] in central Namibia on the effect of fire history on soil nutrients, and [15] northeastern Namibia on the effect of anthropogenically induced fire on vegetation (trees, shrubs, and herbs), and also a study on vegetation secondary succession in response to time since last fire in central Namibia by [16]. However, a gap in knowledge persists to date concerning the effect of fire occurrence, and season, on tree species density in woodland habitats in Namibia specifically the Kavango West Region. This is despite the continuous promotion of fire as a management tool and its use by communities primarily for agriculture. A reduction in this knowledge gap is urgent as different fire seasons may produce differences in tree density, tree size, and tree diversity [34]. Therefore, this study aimed to improve our understanding of the effect of fire occurrence, and seasons, on tree species density in a woodland system. Using data collected from the experimental plots, we assessed the effect of fire occurrence on tree densities. We aimed to investigate the effect of [1] the effect of fire season on tree densities (F1 (Mar/Apr/late wet season), F3 (Jun/Jul/dry season), and F4 (Oct/Nov/late dry season)), [2] fire occurrence on tree density (burned versus unburned).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

- The study was conducted in the Makambu Fire Burning Experiment in the Kavango West Region, northeastern Namibia (Fig. 1, 18.00°E and 22.00°E, and 17.09 and 18.01°S). This experiment was established in 1959 by the Ministry of Agriculture Water and Forestry. Their objective was to study the effect of fire during various seasons on the vegetation with emphasis on the basal area increment and regeneration of the more valuable timber species.

| Figure 1. Study area map location of Makambu Fire Burning Experiment in Kavango West Region in Namibia |

2.2. Sampling and Measurements

2.2.1. Experimental Plot

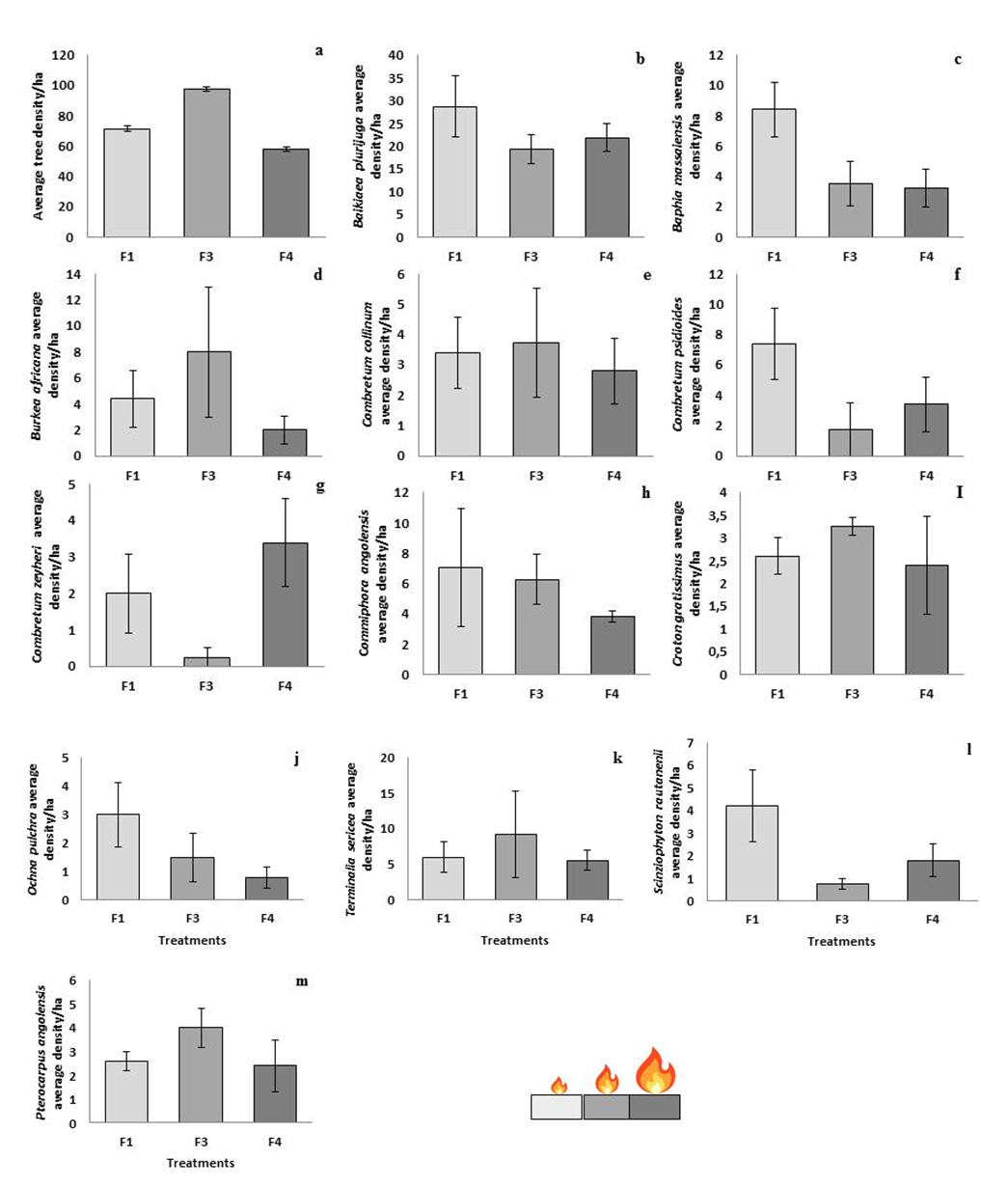

- The study was a quantitative completely randomized block design consisting of 25 plots with five belonging to each of the five treatments including a control (no fire) (Figure 2). Only 20 plots were sampled, and all F2 plots were excluded because in them fire was intensified by placing dead dried branches around species (with a height of 3m and above and with a diameter at breast height (DBH)) that were of interest to the ministry and this burning did not fit our scope. Therefore, we only included F1, F3, F4, and the control. Each block is 1 ha in size separated by 2.5 m of fire breaks. The three distinct fire regimes burned at separate times of the year every year. The burning in the study area occurred in (March/April/ late wet season), (June/July/ dry season), and (October/November/ late dry season).

| Figure 2. Experimental plot layout at Makambu fire trials experimental plots in Kavango West Region in Namibia (b) |

2.2.2. Vegetation Sampling

- Vegetation surveys were carried out in August 2021 across the 20 plots. In each plot, three 20 x 20 m quadrats were placed along a diagonal. To lessen edge effects, quadrats were placed 10 meters away from a plot boundary. Within each quadrant, all live trees (individuals > 3 m) were counted. Species-specific tree density was estimated as individuals/ha and was averaged throughout the three quadrats.

2.3. Data Analysis

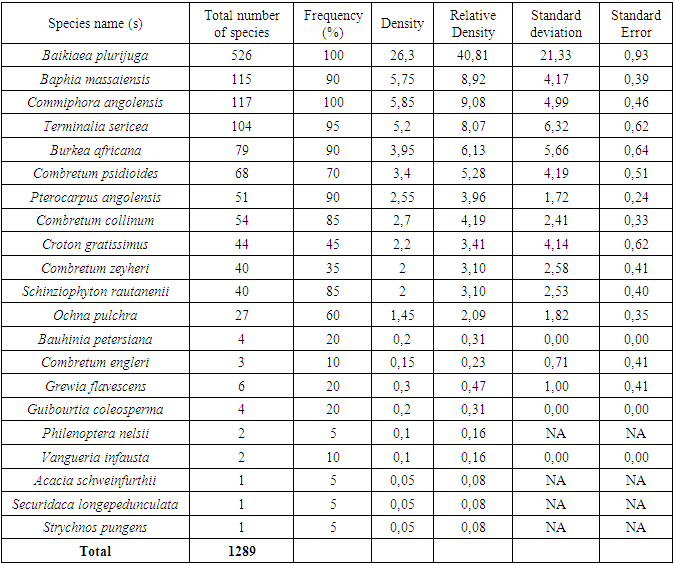

- Statistical analysis were performed using Excel (2020 version), and the PAST statistical package (4.04) [21]. The structure of the woodland was analysed in terms of frequency, density, Relative density, standard deviation and standard error of all tree species (Table 1). The analysis was carried out using Microsoft Excel Program. Accordingly, density that refers to the number of all individual plants of a species per unit area was computed using the formula below and expressed on a hectare basis following an example from [22].Frequency was determined by dividing the number of occurrences of a species by the total frequencies of all species multiplied by a hundred.Density = number of individuals of a species/ area of quadratRelative density (RD) = (number of individuals of species A/ total number of individuals in an area) x100Standard error= standard deviation/√ (sample size)The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality was applied to the fire occurrence and fire season as well as on species-specific trees data for fire occurrence and season. Objective 1) to compare the effect of fire season on tree density (March/April/ late wet season), (June/July/ dry season), and (October/November/ late dry season), the One-Way ANOVA and the Kruskal–Wallis test by [23] was used to compare the sample medians that were found to follow and not the normal distribution, respectively. As such a univariate One-way ANOVA was used to compare the sample median of the three seasons (late wet season, dry season, and the late dry season) in PAST statistics software. While the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the effects of fire season on individual tree species. For objective 2) The One-Way ANOVA and Mann-Whitney (U) tests were used to compare the means of any two datasets that were found to follow and not the normal distribution, respectively in the fire occurrence data (burned and unburned). As such, a univariate One-way ANOVA was used to compare the means of the two groups (Burnt and Unburnt) in PAST statistics software. While the Mann-Whitney (U) test was used to compare the effect of fire occurrence on individual tree species between the burnt and unburnt plots.

3. Results

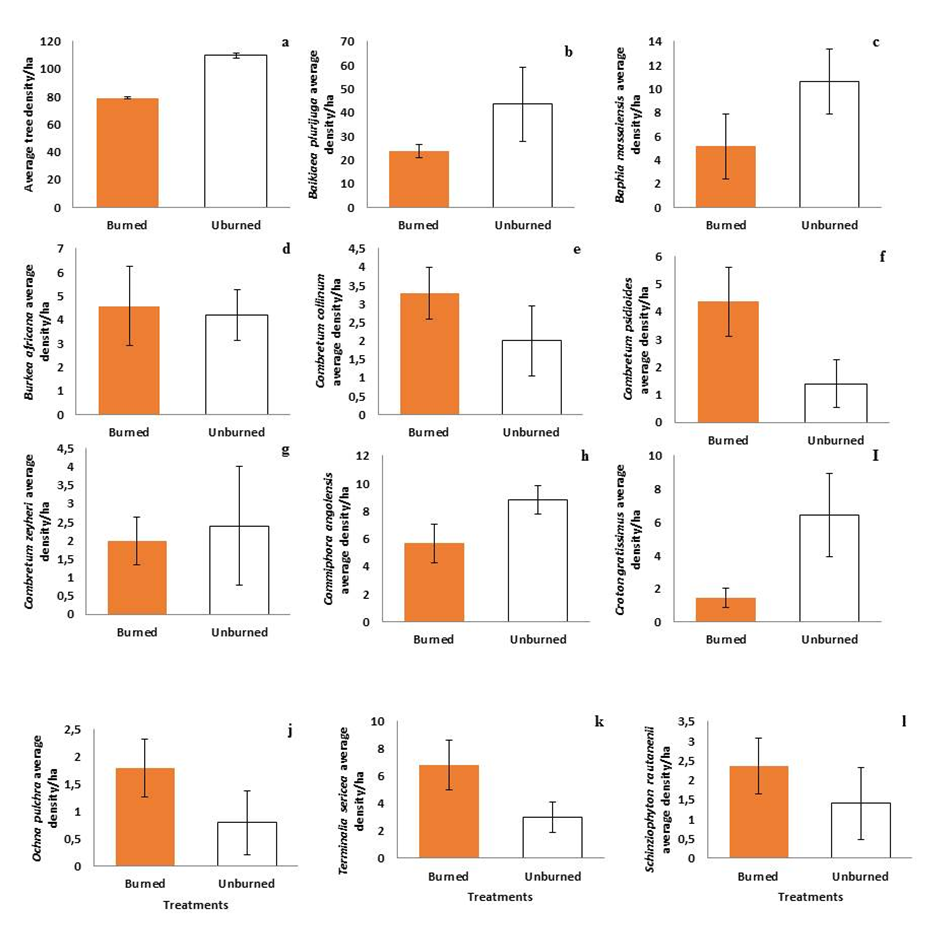

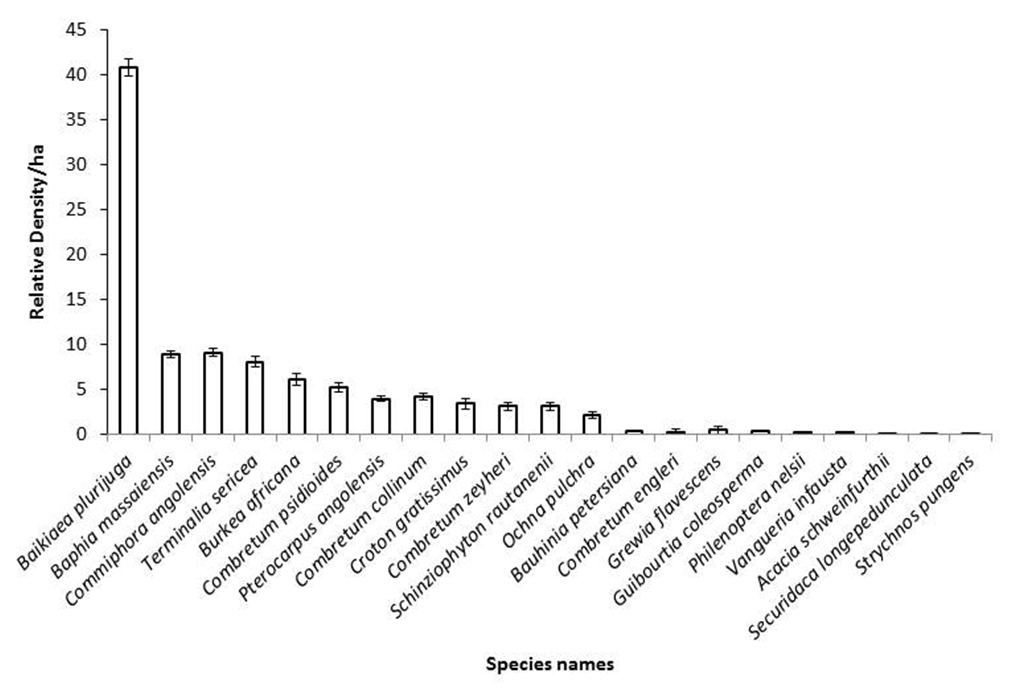

- A total of 21 tree species were identified in the study area, with individual plots containing tree relative densities ranging from 40.81 to 0.08 individuals/ha. The more common species were Baikiaea plurijuga with a relative density of 40.81 trees/ha, Baphia Massaiensis, Commiphora angolensis, Terminalia sericea, and Burkea africana; and the least common species include the Combretum psidioides, Pterocarpus angolensis, Combretum collinum, Croton gratissimus, Combretum zeyheri and Schinziophyton rautanenii with their relative tree density ranging from (5.28 to 3.10 trees/ha). While the lowest-value trees were Ochna pulchra, Bauhinia petersiana, Combretum engleri, Grewia flavescens Guibourtia coleosperma, Philenoptera nelsii, Acacia schweinfurthii, Securidaca longepeduncula, and Strychnos punges, with their relative density ranging from (2.09 to 0.08 trees/ha) Figure 3, Appendix Table 1.

| Figure 3. Relative density per ha for the entire sampled area, error bar indicate the standard error bar |

4. Discussion

- Our findings revealed that fire season had a significant negative effect on tree density with the largest declines were registered in the late dry season, followed by late wet season and the least in the dry season. This gradient is in agreement with our original hypothesis. A similar declining effect was observed at the community level and species level with the exception of Baphia massaiensis and Croton gratissimus which had higher tree densities in unburnt plots.Effects of Fire Season on tree densities Our finding of a decrease in tree density with gradient in fire treatment from dry to cold seasons was expected and in concordance with previous studies. This trend can be explained by the interaction in the trends between environmental variables and the vegetation phenology state. The late dry season is characterized by high ambient temperatures, daily maximum temperature of above 40°C are recorded daily, average monthly temperatures ranging between 24°C (November to March) and 16°C (June, July) in Namibia [24] and coincides with the timing when the vegetation moisture content is low and in general trees become more flammable [4]. In addition to these, fires occurring in October are the most intense as a result of a buildup of dry fuel loads; this is because increased fuel load leads to higher fire intensity [25]. Hence, the lower tree density in the plots subject to late dry season fire application was expected. Following this line of thinking, findings suggest that fire application in the late wet and dry cold seasons constitute minimal disturbances relative to late dry season. These scientific findings are in agreement with the Namibian Fire Management policy as well as the SADC Fire Management Programme (2010) [26] which discourages late dry season burning due to its devastating effect on the environment. According to the SADC Fire Management Programe as well as the Namibia Fire Management Policy [26] it is more convenient to conduct fires no later than March the reason is that fire in March reduces hazardous forest fuels. This could be related to our results as well, consequently, the lack of significant difference in our results. F3 (Jun/July/dry season) is the driest and coolest season in Namibia as well as in our study area. Burning around this time could have caused some tree species densities to change but as observed in our results this season of burning had the highest tree density in comparison to the other seasons. This result could have arisen due to the observed inconsistency in burning by the foresters, whereby sometimes burning happens a little bit earlier or later in the season. Therefore, promoting tree growth, and resulting in a lack of significant difference when comparing the tree densities of the three burned seasons. To add on, the plots only burn once a year, meaning that there is a year-long fire return interval, and the trees stand a good chance to recover from fire damage until the next circle of burning. According to [6] found that longer fire return periods prevented the loss of woody plant cover in their study; this can be related to our study area as well. With the analysis of the various tree-specific species (species level) densities, it was revealed that there was no significant difference in the effect of fire season between the entire various tree-specific species densities of the F1 (March/April/late wet season) and F3 (June/July/dry season), and F4 (Oct/Nov/late dry season) plots, the lack of significant difference could be the same as the already provided above reasons, less fire intensity, inconsistency in burning, the burning season, etc. this observation in our study is not different from an observation made by [16] in their study in Central Namibia. It's also possible that the reason for the lack of variation was caused by the reduction in biomass/low fuel load which was insufficient to support fire that could alter the trees, as observed by [16] in their study in central Namibia. The presence of cow dung in the area is also a sign that animals are grazing/browsing in the study area reducing species at ground level, therefore, leading to a lack of significant difference among the tree-specific species densities of various trees in different plots of different fire intensities and burning seasons. In a related example, the same was discussed by [27] that human settlement in the Caprivi in Bwabwata National Park led to an increase in the number of cattle that removed a larger percentage of the fuel load in the grassland or woodlands. [20] also indicated that heavy browsing by livestock and wildlife can also affect tree growth and cause seedling mortality, affecting tree density in the long run.Effects of Fire Occurrence (Burnt vs Unburnt)Our findings reveal a significant difference in tree density regarding the impact of fire occurrence (burnt and unburnt) on tree species densities at the plot level (i.e. community). The unburned showed a higher density of 109.6 (±SE1.543) species/ha while the burned plots revealed a lower density of 79.0 (±SE0.920) species/ha. This result of higher tree density on unburned plots is in agreement with findings of [28]. In their study [28] in the United States, this revealed that complete protection from fire and reduction in fire frequency increased woody canopy biomass. The lower tree species density attributed to the effects of fire, suggest negative effect of fire on tree species density, such results indicate that some of the species were lost during the burning and they were not replaced by fire-tolerant species [29] which could have maintained a high tree density in the burned plots. The local extinction of tree species can be because tree species encountered fire at different stages of growth, but responses may differ across species with some having a higher survival rate than other. This effect if further accentuated if fire are frequent and or occur during the early growth stages of a tree species, causing damage [30,31] that resulted in a significant difference in the tree density between the burned and unburned plots. At the species level, densities were found to be similar, between the burned and the unburned plots, except for Baphia massaiensis and Croton gratissimus tree density. These results are similar to studies of [32,33], where there was no significant difference observed in burned and unburned sites on the species richness in semi-arid savanna woodlands in Namibia, also there was no significant difference in terms of species richness and species diversity respectively. [29] Reports about fire having little effect on the density of the burned and unburned sites in their study. Similar findings were recorded by [34,35]. Numerous elements might affect the extent of tree destruction, and one of them could be the intensity of the fire, which would explain why there isn't much of a difference in the trees between the burned and unburned areas. There might be comparable tree densities in burned and unburned areas when it comes to specific species; this may be due to this suggestion that the severity/intensity of the fire was not great enough to affect tree mortality greatly. [29,36] suggest that an increase in the frequency or severity of fires will likely change the tree density. Another factor that could affect the impact of fires on the density of trees is tree clustering. For instance, [29] found that clustering reduces the damaging effect of fire on trees in African savannas. Baphia massaiensis and Croton gratissimus exhibited a noticeably higher density in the unburned plots than in the burned plots. One main reason which may explain this difference is that, fire protection increases density and favors fire-sensitive species, these (Baphia massaiensis and Croton gratissimus) two species are slender with a fine bark [37]. These traits render these to be more prone to fire and easily combusted [38] writes that the ability of a plant to withstand fire not only depends on the prevailing fire regime but equally on the sizes of the plants. Arguably because of such traits, shrubs are more susceptible to fire than trees and as reported by [39] shrub-lands tend to be more susceptible to fire than thicker stemmed plants [39]. In general, the absence of fire can either promote or suppress the growth of tree and shrubs species. Therefore, according to the above reasons it could be the case of Croton and Baphia in our study area resulting in a higher density of the two tree species in the unburned plots due to the absence of fire when compared to their density in the burned plots.

5. Conclusions

- We show the effects of late wet season, dry season and late dry season fires on tree densities as well as the effects of burning and not burning on tree densities in Kavango West Region. Although our findings can only be related to experimental type of research, still it should be noted that fire regulates the composition and structure of many terrestrial ecosystems. Burning reduces tree densities, our findings informed that the unburned plots showed a higher density of trees/ha in comparison to the burned plot and complete protection increased tree densities. Therefore, there should be a reduction in the extent of burning in the region. Similarities in response of fire effects among trees at the species level were observed both in the burned and unburned plots, in exception of Croton gratissimus and Baphia massaiensis, this dissimilarity in response on fire effects on this two species may be due to a variation in response to the trees to their functional traits. Our findings further revealed that the Oct/Nov season exhibited lower tree density/ha than the two other seasons Mar/Apr and Jun/Jul. Oct/Nov is the late dry season the trees at that time have low moisture content and are easily flammable, fires around this time are most intense because the conditions are usually dry and fuel loads are high. The various specific species had no significant difference in density per season; this could be because of less fire intensity. Entirely these findings reinforce already existing Fire Management Practices in the Namibian fire Policy, which discourages burning during the late dry season due to the devastating effects of fire on the environment as well as the vegetation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML