-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Ecosystem

p-ISSN: 2165-8889 e-ISSN: 2165-8919

2016; 6(1): 14-24

doi:10.5923/j.ije.20160601.03

Analysis of Conversion of Forest Land to be Oil Palm Plantation Area in the District of North Barito Central Kalimantan Province

R. Muratni 1, Maryunani 2, I. Hanafi 3, A. Kurnaen 4

1Doctoral Program of Environmental Studies and Development (PDKLP), University of Brawijaya, Indonesia

2Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia

3Faculty of Administration Science, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia

4Faculty of Forestry Science, University of Lambung Mangkurat, Indonesia

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Externalities of conversion of natural forests into oil palm plantations will lead to costs, both environmental costs and social costs. It means that every change in forest area there will be a mechanism or process that is directed back to the condition of the balance between costs and benefits. Paradigm of sustainable forest management into the theoretical foundation of this research is to explain the phenomenon of the conversion of forests into oil palm plantation area in North Barito District. The aim of this study that the conversion of forest areas should be able to provide added value to a better economy with fixed regional development can create new ecosystem balance that remains supportive environment. The results showed that at five (5) years (from 2009 to 2014) there has been a conversion of forest areas into oil palm plantations in North Barito continues to increase. Improved forest area changes caused by inconsistencies between the policies of governance of forest resources with the actual land use in the area, especially during the era of autonomy. Oil palm plantations produce economic value of IDR 815,626,000,000. The ecological value of forest areas which have been converted to IDR 82,996,234,400 coupled with the social cost of IDR 714,000,000. When combined between ecological values are sacrificed by social costs borne by society will accumulate IDR 83,710,234,400. Results of this analysis explains that the change of forest larea into oil palm plantations in the district of North Barito more favorable to the development of oil palm plantations amounting to IDR 731,915,765,600. Social costs of the conflict due to land is an indicator of the vulnerability of the social impacts of changes in forest land in North Barito District which has the character to continue to increase in each year.

Keywords: Conversion of forest land, Oil palm plantations, Benefits Cost

Cite this paper: R. Muratni , Maryunani , I. Hanafi , A. Kurnaen , Analysis of Conversion of Forest Land to be Oil Palm Plantation Area in the District of North Barito Central Kalimantan Province, International Journal of Ecosystem, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 14-24. doi: 10.5923/j.ije.20160601.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Forests as part of the natural resources increasingly threatened. The level of forest exploitation is not coupled with supervision while promoting sustainable forest management is not a reference. During the period of 63 years (1950-2012), forest cover in Indonesia decreased from 162 million ha to 88 million ha. According to the Indonesian Climate Change Sectoral Roadmap (ICCSR), the causes of deforestation Indonesia due to fundamental problems, among others, are: (1) conversion of natural forests to perennial crops, (2) the conversion of natural forests into agricultural land, (3) exploration extractive industries in forest areas (coal, oil and gas, geothermal), (4) forest and land fires, and (5) conversion to transmigration and other infrastructure. In addition to the above five factors, in some areas of forest damage actually caused by the expansion of new autonomous regions.The World Bank estimates that natural lowland forest of Sumatra runs out in 2005 and followed Borneo in 2010. The latest data says that the rate of deforestation in Indonesia has reached 2.83 million ha per year (MoF, 2010). The high conversion of natural forests into various land use is believed to be the major cause of high intensity and frequency of floods and landslides, as has now occurred in many areas of the motherland. It was realized that the conversion of natural forests do not always have a negative impact, not even a little bit of success stories over the function of forests into land use, more productive and sustainable. Conversion of natural forests into rice fields, tea plantations, rubber and various forms of farm, including oil palm plantations in Java, Sumatra and Kalimantan have proven that the natural forest conversion does not always show the face that are less environmentally friendly.Utilization of excessive economic functions of forests by humans (exploitation of forests) without regard to the ecological balance could be disastrous for the man himself, and costs and social economy far greater than the economic results have been obtained. Form of economic use is converting forest into oil palm plantations. Oil palm plantations has been happening because the conversion of natural forests. Ecologically it is damaging the natural forest habitat that would destroy the entire forest biological wealth of invaluable prices and benefits, but it also will change the landscape of natural forest in total. This process, if not done properly (and usually does) will have an impact on the entire ecosystem damage Watershed (DAS) that are below. Impact, among others, is the increased flow of surface (surface runoff), landslides, erosion and sedimentation. This condition is getting worse, if the land-clearing (after the timber felled) is done by burning.Externalities of conversion of natural forests into oil palm plantations will lead to costs, both environmental costs and social costs. It means that every change in forest area there will be a mechanism or process that is directed back to the condition of the balance between costs and benefits. Suhendang (2004) that the forest management is needed understanding of the existence and role of the components of the forest ecosystem, with an approach that is comprehensive, integrated and sustainable. There are three schools of thought forest management are: (1). According to the pattern of spread function space, with forest allocations based on the biophysical characteristics into various functional use and any kinds of functions are managed with one main objective manner. (2). The pattern of use of space in an integrated and intensive, that any forest land is intended to provide overall functions of the forest as an ecosystem. This pattern is theoretically ideal and suited to characteristics of natural forests to vast areas increasingly limited, but its implementation is difficult, because the concept and the technology is still very limited, (3). A combination of the spread pattern with integrative and intensive space, namely forest area allocated to use by biophysical characteristics, then the management at each function of the forest was directed to obtain some function or the benefits they afford through process optimization functions.The third school of thought is more ideal than the first and more realistic in the operation on the ground in the present rather than the second. It also supported with the basic principles of forest ecosystem management is the use of science integrated, comprehensive and latest (Cortner, 1990 in Czech, 1995). Gordon (1994) suggested five concepts in the implementation of management, namely (1) manage the local circumstances, (2) governance with the attention to the public interest, (3) manage the unity of space or landscape intact, (4) management based on knowledge of the mechanisms not ecologically simple rules in outline, (5) governance without negative externalities.Human linkages with forest appear in human knowledge in managing forest land. How that is done by humans in forest management, among others, namely: change of natural forests into oil palm plantations will reflect on how forests are viewed and utilized. Changes in natural forest areas requires knowledge of forest maintenance management (Lawrence, 1995). Phenomenon to changes in natural forests into oil palm plantations also occur in natural forest areas in North Barito District of Central Kalimantan. Changes in natural forest area is empirically will cause problems multiplier effect which is based on the social life of the community, the problem of pressure on the environment, pollution and environmental damage.Therefore that the conversion of natural forests should be based on the concept of sustainable forest management. Paradigm of sustainable forest management can be grouped into four, as the adoption of the sustainable development paradigm that is expressed Turner (1993), namely (1) sustainability is very weak, (2) weak sustainability, (3) strong sustainability and (4) sustainability is very strong. Perspective of sustainability requires a paradigm shift towards the paradigm of sustainability robust and very strong (ecocentric), because the paradigm sustainability is very weak and weak (technocentric) less attention to the capacity of assimilative environment, critical factors of natural resources such as species and processes the ecological base that can not be replaced by artificial resources, as well as the complementary nature of components in the system's structure and diversity is vital to the resilience of the system.Paradigm of sustainable forest management into the theoretical foundation of this research is to explain the phenomenon of the conversion of forests into oil palm plantation area in North Barito District. The aim of this study that the conversion of forest areas should be able to provide added value to a better economy with fixed regional development can create new ecosystem balance that remains supportive environment.

2. Research Methods

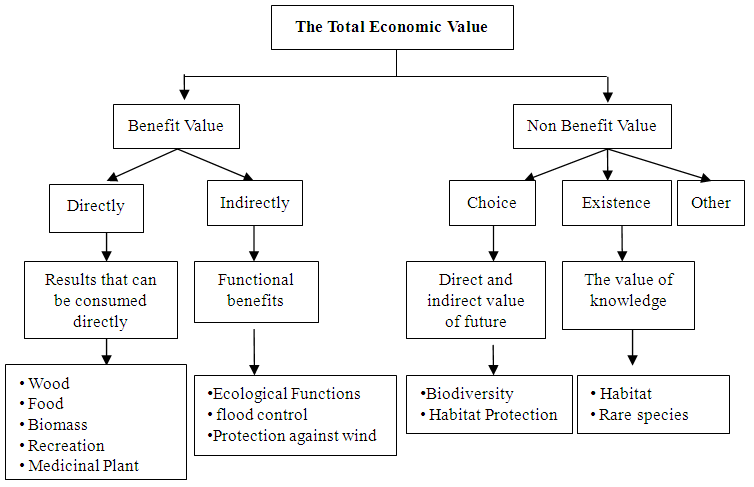

- This study was conducted in North Barito district administration area with the consideration that the region consists of more forest area consisting of: (1) Forest area of 889,331.98 hectares (87.45%), (2) Non Forestry Cultivation / Other Use Areas covering 127.641,55Ha (12.55%). (3) Holding Zone (forestry activities that go beyond the forest) area of 840,668.73 hectares (82.66%), (4) Preserve Forest (72.630,98Ha), (5) Aquaculture Forestry (816.710,00Ha), (6) Non Aquaculture Forestry (217.447,55Ha) and (6). Outside activity of Forestry (Holding Zone) 851,695.61 Ha.Identification of forest benefits through the approach of Total Economic Value (TEV) with respondents interviewed through a questionnaire guide. The total economic value can be obtained from the use value and non-use values of the forest. The total economic value (NET) is the sum of direct use values, indirect use values and non-use values, with the following formulation (Pearce, 1992):

The value of forest resources can be classified by several groups. Davis and Johnson (1987) classify value based method of assessment or determination of great value made, namely: (a) the market value, value is determined through market transactions, (b) the value of usability, value is obtained from the use of these resources by specific individuals and (c) social values, a value is set by regulation, law, or community representatives. While Pearce (1992) in Munasinghe (1993) made a classification that describes the value of the benefits of the Total Economic Value (Total Economic Value) based on the method or process benefits obtained.Oil Palm Plantation investment using financial analysis aimed to assess whether a particular activity undertaken financially feasible, or can provide financial benefits for companies that aim to maximize profits. Financial feasibility of an activity shown by the NPV (net present value), B/C ratio (Benefit-Cost Ratio), or IRR (Internal Rate of Return). NPV, B/C ratio and IRR actually relate to each other. An activity is said to be financially viable (profitable for the company) if the NPV is positive. If a positive NPV means that the value of B/C ratio is greater than one, and the value of IRR is greater than the discount interest rate (discount rate) used in the calculation of NPV. So, one of these values can be used to decide whether an activity will be profitable (feasible) or financially. On the financial aspects of financial ratio analysis is often used to measure the achievements of the aspects of the business (Downey and Ericson, 1992).

The value of forest resources can be classified by several groups. Davis and Johnson (1987) classify value based method of assessment or determination of great value made, namely: (a) the market value, value is determined through market transactions, (b) the value of usability, value is obtained from the use of these resources by specific individuals and (c) social values, a value is set by regulation, law, or community representatives. While Pearce (1992) in Munasinghe (1993) made a classification that describes the value of the benefits of the Total Economic Value (Total Economic Value) based on the method or process benefits obtained.Oil Palm Plantation investment using financial analysis aimed to assess whether a particular activity undertaken financially feasible, or can provide financial benefits for companies that aim to maximize profits. Financial feasibility of an activity shown by the NPV (net present value), B/C ratio (Benefit-Cost Ratio), or IRR (Internal Rate of Return). NPV, B/C ratio and IRR actually relate to each other. An activity is said to be financially viable (profitable for the company) if the NPV is positive. If a positive NPV means that the value of B/C ratio is greater than one, and the value of IRR is greater than the discount interest rate (discount rate) used in the calculation of NPV. So, one of these values can be used to decide whether an activity will be profitable (feasible) or financially. On the financial aspects of financial ratio analysis is often used to measure the achievements of the aspects of the business (Downey and Ericson, 1992).  | Figure 1. The total economic value of forest resources (Pearce, 1992 in Munasinghe 1993) |

| Figure 2. Research Location Map |

3. Empirical Result

3.1. Investment Analysis of Oil Palm Plantation

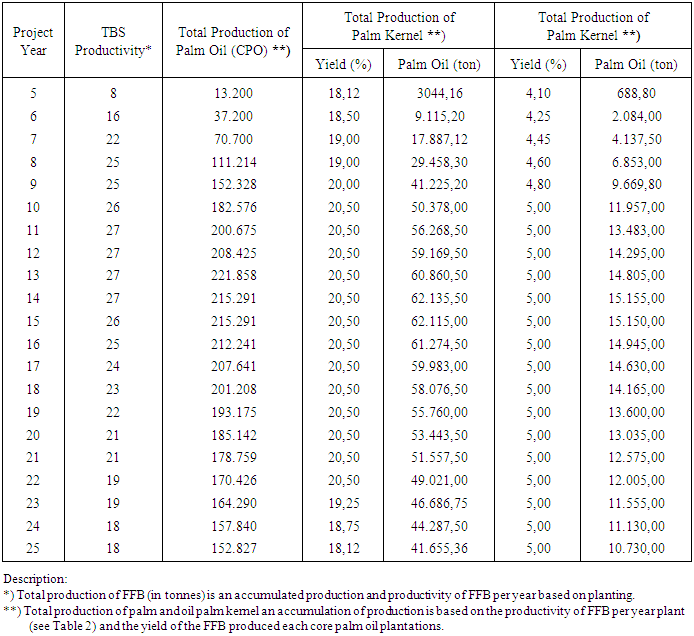

- The study also shows various project costs and benefits of large-scale oil palm plantations (10,000 ha) over the life activities. It also shows the cash flow oil palm plantation investment projects during the period of the life of the plantation. Cash flow consists of flow of expenditure (outflow), ie all costs per year, the value of money, issued by the company during the implementation of activities, and the flow of revenues (inflow), that all receipts per year, in the value of money, received by the company from the implementation of oil palm plantations, ie year-on-0 until the 25th year.Oil palm plantations by using cultivation technology and sophisticated processing must take into account the production capacity of the economy so that the investment in this sub-sector can really provide benefits in the future is therefore important to do a production forecast of oil palm trees to plant fruit fresh produce ready to take to the palm oil mill. Results of the analysis of crop production projections fresh fruit / TBS of oil palm plantations can be seen in the table 1 below.

|

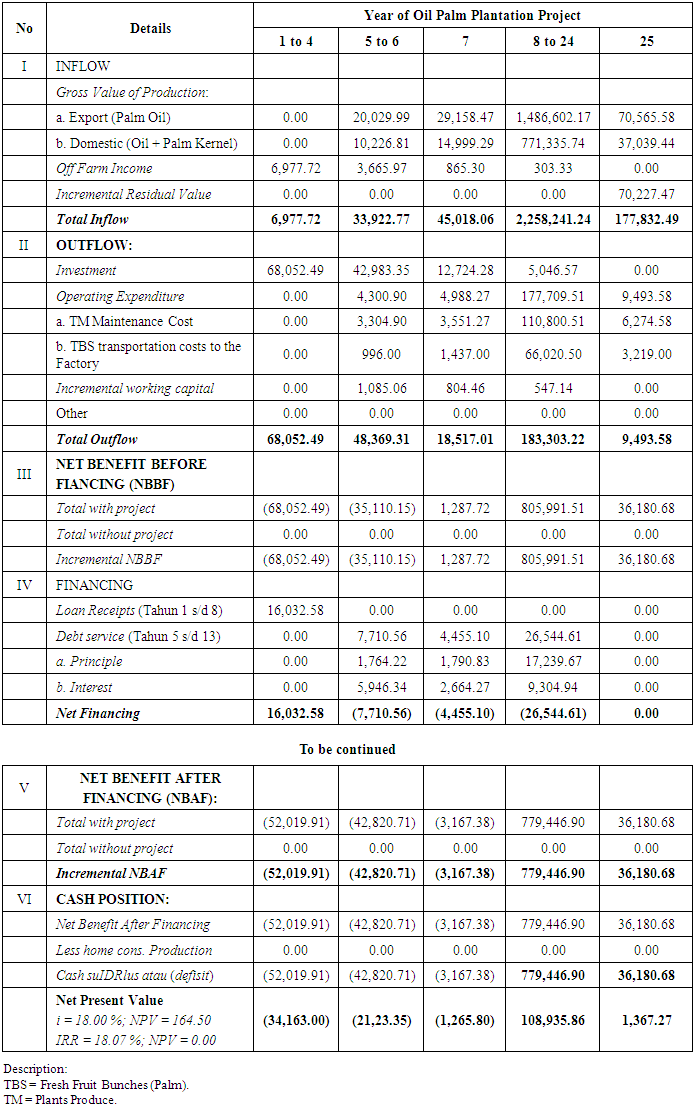

3.2. Financial Analysis of Investment of Oil Palm Plantation

- Investment funds needed to build the Oil Palm Plantation Project amounting to IDR 231,79 billion. NPV on a discount factor (DF) of 18% by oil palm plantations core budget over the life of the project was obtained for the negative USD 1979.88 million, which means that the net value (net benefit) received the project for 25 years now by the negative value of IDR 1,979, 88 million. Meanwhile, the project's ability to restore capital measured by IRR of 17.16%.CPO export price previously set at IDR 1,288 / kg when adjusted to international price range but still have a competitive price, it is likely that the project plan can be executed. By paying attention to the world CPO price in the year 2010-2014 which is above the $ 35.0 Cts / kg, assuming the exchange rate of US $ 1 equal to IDR 13,500, and in this project rupiah value is set to 50% overvalued against the US $ to US $ 1 became equal to IDR 13,750, then the price of Indonesian CPO exports should IDR 1312,5 / kg. At this price level NPV (DF = 18%) amounting to IDR 164,50 million and an IRR of 18.07%. Results of the analysis of financial feasibility of large oil palm plantation project in the district of North Barito fully explained in the table 2 below.

|

3.3. Ratio Analysis

- The value of net profit margin (NPM) remained normal, with positive values began in the 9th year, because from year 1 to year 8 core company is being invested. Furthermore, beginning in the 12th until the project ends NPM relatively stable values ranged from 0.45 to 0.49. NPM means any income 0,49 USD 1 resulted in a net profit after tax of IDR 0.49. Meanwhile, from the return on investment (ROI) that indicates the ability of each USD 1 assets to generate earnings showed positive values starting in the 9th. Stable ROI of 0.14 obtained in the 15th until the end of the project. ROI of 0.14 means that every US $ 1 of assets the company is able to generate a profit of IDR 0.14.The liquidity ratio shows the company's ability to meet obligations short term. Rated current ratio and cash ratio has shown a positive figure in the early operation of the project, and on the 13th the amount of 118.85. Cash ratio of 118.85 means that every US $ 1 of short-term liabilities secured by cash and marketable securities amounted to IDR 118.85. And starting the year 14 until the project ended liquidity ratios infinite magnitude, since the core company no longer bear the short-term liabilities.The value of fixed assets to long term liabilities ratio is infinitely long economic life of the project, because of companies not bear the burden of long-term debt. Meanwhile, the value of equity to total assets ratio of its positive value in the 8th until the end of the project ranged between 0.25 - 1. The information indicates that the core of the company is quite solvent / laverage. But keep in mind, that if contributions (capital) owners of less than 50% of the net assets of the company, the company is experiencing solvency problems, and it is difficult to enlarge the loan if necessary.Efficiency ratio of the company with one measure is the total asset turnover (TATO) also appeared normal and values ranged from 0.10 to 0.73 since the project started operating until the end. TATO value of 0.73 means that of all assets owned by the company's core capable of generating revenue of 0.73 time.

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

- Sensitivity analysis aims to see what would happen to the results of the project if there is something wrong or changed in the basics of calculating costs or benefits are (Djamin, Z., 1993). In this regard, oil palm plantation projects showed a high sensitivity when in view of the value of IRR is slightly larger than the social discount rate of 18%. At a slightly higher IRR or nearly the same as the social discount rate (18%), when the swelling little investment, or an increase in export taxes a little, or even an unexpected decline in output prices slightly from USD 1312.5 / CPO kg, then the result of this project is not a competitive investment. Thus, one of the efforts to be undertaken by the project initiator is trying to lobbied the lender so that the social discount rate could be lower than 18% and lobbied the government to sensitive projects can obtain tax relief in the form of export subsidy by considering the social benefits of the project.

3.5. Social Benefits / Economics

- Can not be ignored the fact that in addition to financial benefits, each project is also expected to provide social benefits (economic) others. From this project, the expected economic benefits are: (1) the addition of national income; (2) the addition of foreign exchange, considering that 70% of CPO is an export product; (3) expanding employment opportunities, because this project requires a workforce of around 5,650 families or about 22,600 peasant family workers and farmers, so as to reduce the problem of unemployment in Indonesia (especially in South Kalimantan); and (4) adding the tax revenue, especially taxes of imports of equipment and machines for the project, the resulting product export tax project, employee income tax and dividend tax.With reference to Table 2, which has produced results The financial feasibility analysis of oil palm plantations in District of North Barito (USD million), it can be concluded that: (1). The construction project of a large oil palm plantations will start generating profits starting in the 8th until the 24th year of IDR 779,446,000,000.90, (2). The construction project of a large oil palm plantations also generate profits starting in the 25th IDR 36,180.000.000,68 and (3). So the development of oil palm plantations with large plantation category will generate a profit of IDR 779,446,000,000.90+IDR 36,180,000,000.68 = IDR 815.626 billion.

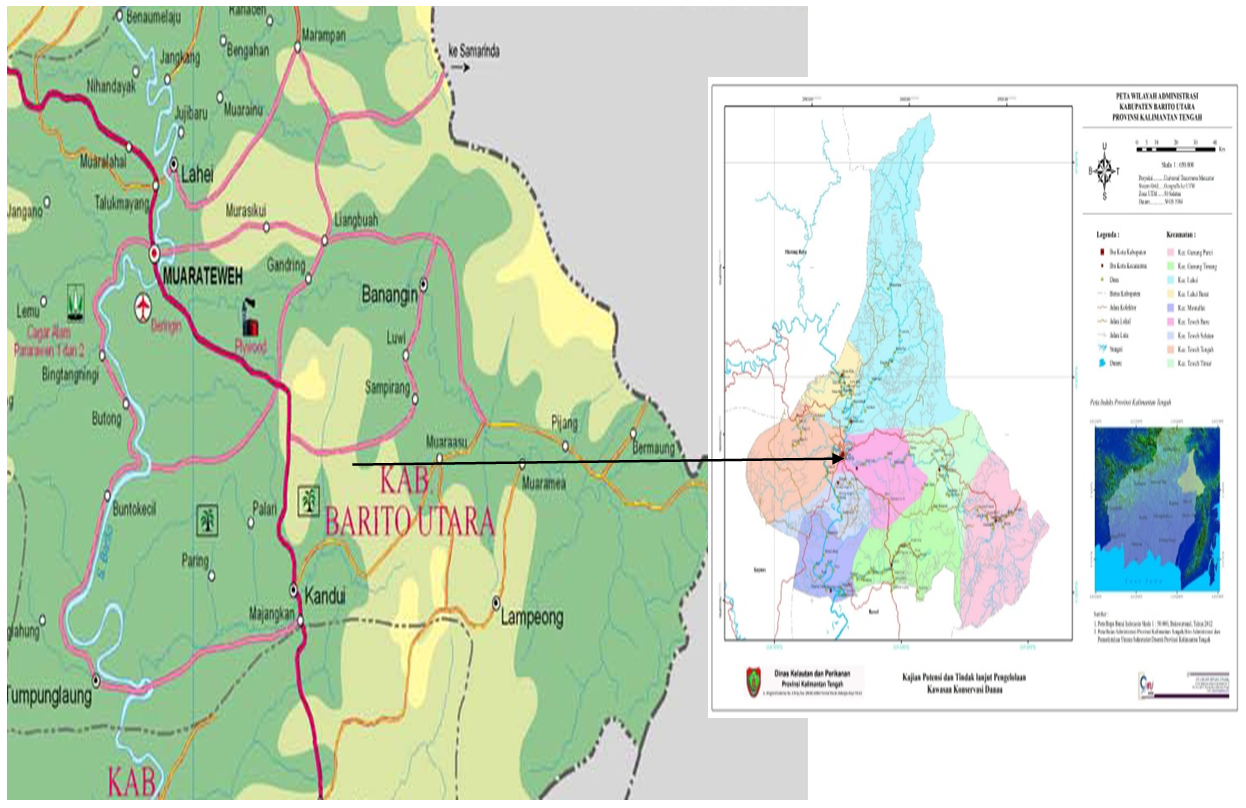

4. Cost of Environmental and Social Costs

4.1. Environmental Costs (Environmental Costs)

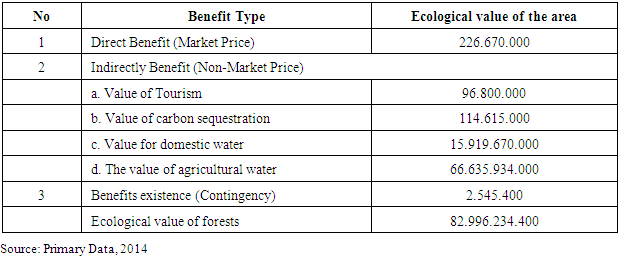

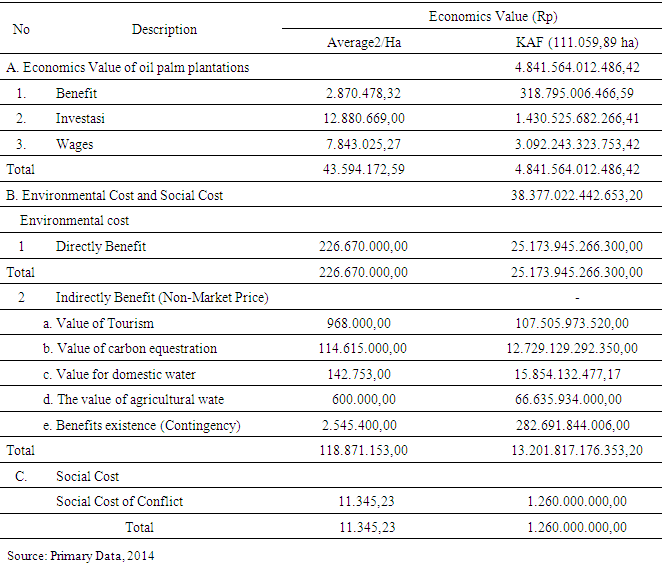

- Conversion activities in forest areas for the development of oil palm plantations in North Barito District there are any that environmental costs and social costs. Environmental cost is the value of the ecological benefits of forest will be lost in the event of conversion to palm oil plantation area.Environmental costs are all costs incurred due to damage and/or environmental problems as a result of the implementation of certain activities, such as oil palm development. In other words, the development of oil palm plantations by converting wet tropical forests have a negative impact on the environment. The negative impact on the environment is indeed an economic loss to be paid by the public and / or other parties.The identification results of all the ecological benefits of forest land in North Barito District which has been identified by assuming the conversion of forest land area of 10,000 hectares (Category Large private plantation). Details ecological value of the benefits of each can be grouped into two, namely Direct Benefits (market price) and Indirect Benefits (non-market prices). Explanation of such benefits ilihat in the table 3 below.

|

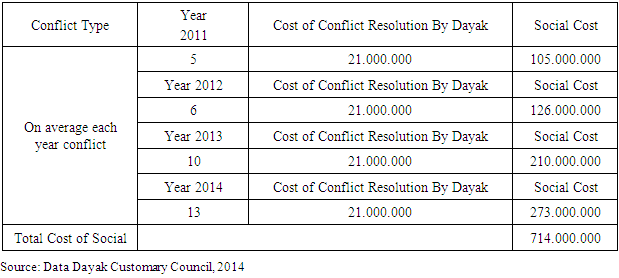

4.2. Social Costs

- Social costs in this study is based on the cost of completion used to resolve conflicts that occur due to changes in land in North Barito District. Dayak Customary Council explained that any forest land conflicts resolved through the mechanism of indigenous Dayak Customary Council meeting after it is done with the traditional ceremony in which there are concentrations of indigenous decision to obey. On forest land conflict resolution at Tribal Council will be followed by a traditional ceremony in which implementation costs. Costs of conducting traditional ceremonies associated with the settlement of forest land reaches approximately USD 21 million. The costs associated with the implementation of traditional ceremonies, such as: infrastructure, materials for traditional ceremonies, publications and administration. If the annual average conflicts forest land based on Table 4 it will be known social costs of changes in forest land into oil palm plantations in North Barito District.

|

5. Results Analysis of Changes in Forest Land being Oil Palm Plantation

- Damage to forests caused by several factors One factor that is interesting to study the issue of change (over) forest area (Joseph, 2004; Verbist, 2004). Changes in forest area can be any zoning changes among which oil palm plantations. According to Wahyu (2014), in order to obtain optimum benefit to the public welfare, basically forest areas can be utilized with due regard to the nature, characteristics, and vulnerabilities, and is not allowed to change a forest area that has a protective function. In the utilization of forest areas must be adapted to the principal function is the function of conservation, protection and production. The third suitability of the function is very dynamic and the most important is that the utilization should remain synergies.Oil palm plantations do not actually need to be built on an area of forest (conversion) is still productive. But with the objective interests of regional development and economic growth forest conversion continues. Forests are converted continued to rise. If carried out on the analysis of the results of this study resulted in a choice (of trade) between economic interests and ecological interests. Comparison between the function of the oil palm plantation with the function of forests can be seen in the table 5 below.

|

6. Conclusions

- This study describes the conversion of forests into oil palm plantation area in North Barito District. The results provide the following conclusions:1) At 5 (five) years (2009 to 2014) there has been a conversion of forest lands into oil palm plantations in North Barito continues to increase. Improved forest land changes caused by inconsistencies between the policies of governance of forest resources with the actual land use in the area, especially during the era of autonomy.2) Oil palm plantations produce economic value of IDR. 815,626,000,000. The ecological value of forest areas which have been converted to IDR 82,996,234,400 coupled with the social cost of IDR 714,000,000. When combined between ecological values are sacrificed by social costs borne by society will accumulate IDR 83,710,234,400. Results of this analysis explains that the change of forest land into oil palm plantations in the district of North Barito more favorable to the development of oil palm plantations amounting to IDR 731,915,765 600.Results of the research that has some suggestions related to the conversion of forests into oil palm plantation area as follows:1) Economic, ecological and social needs to be done in integrated management taking into account local resources on an ecosystem component area of oil palm plantations to realize sustainable development in the region.2) Granting or extension of the concession to the oil palm plantation companies in the future should consider indigenous rights and the territorial value of the area adjacent to the residence and township to build a pattern of positive interaction / associative between companies and communities. Highly recommended exercising their plasma plantation development community as implied by the Forestry Minister's Regulation No. P. 39 / Menhut-II / 2013 on Local Community Empowerment Through the Forestry Partnership.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML