-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Ecosystem

p-ISSN: 2165-8889 e-ISSN: 2165-8919

2015; 5(4): 91-98

doi:10.5923/j.ije.20150504.01

Status of Nilgiri Biosphere in 2015

Shobha Kumari

Molecular Lab, Department of Anthropology, North Campus, University of Delhi

Correspondence to: Shobha Kumari , Molecular Lab, Department of Anthropology, North Campus, University of Delhi.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Biosphere Reserves are representative parts of natural and cultural landscapes extending over large area of terrestrial or coastal or marine ecosystems or a combination there of and representative examples of bio-geographic zones or provinces. These regions of environmental protection roughly correspond to International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Category V Protected areas in which one of them is Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve represents a Biodiversity-rich ecosystem in the Western Ghats-a global biodiversity hotspot also provides an ideal habitat for supporting a high degree of endemic flora and fauna. A variety of human cultural diversity can be found in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. Aim of the present study is to highlight the status of Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve in 2015. The objective of the present study is in the increasing population or migration from surrounding areas rather than the population growth of indigenous people in Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve has been enduring human interference for a very long time through development projects such as hydroelectric power projects, agriculture, horticulture, etc., which have brought about substantial change in the ecology of the area. Many environmental problems are noticed in different parts of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. But from the efforts of conservation law the forest cover has no negative change after 1999 which indicates that strict conservation efforts were taken up by state forest departments of Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Keywords: Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, Flora and fauna, Interference, Conservation

Cite this paper: Shobha Kumari , Status of Nilgiri Biosphere in 2015, International Journal of Ecosystem, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 91-98. doi: 10.5923/j.ije.20150504.01.

Article Outline

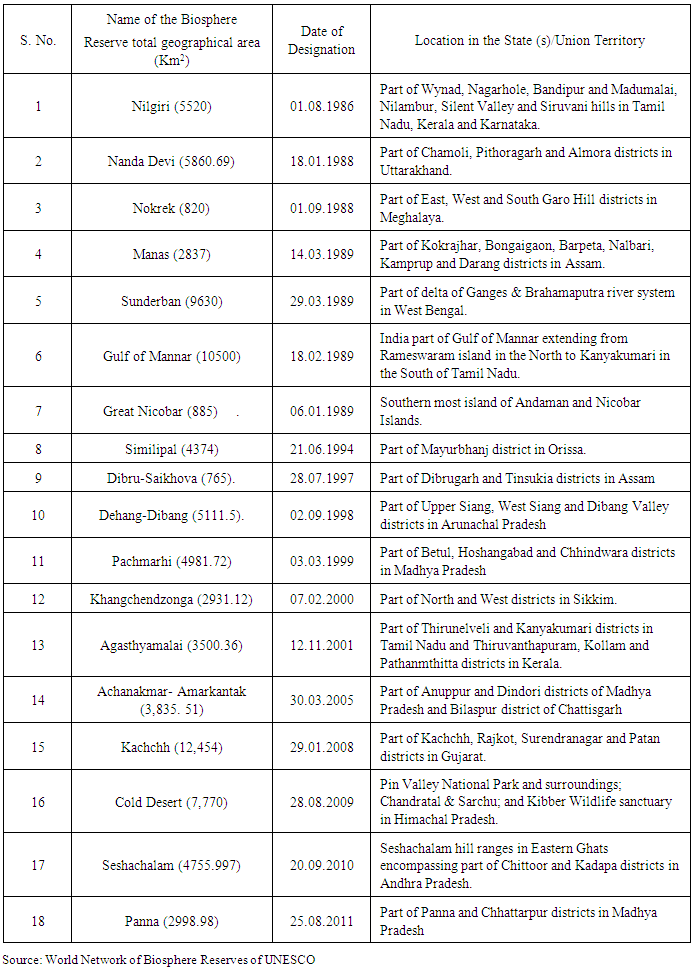

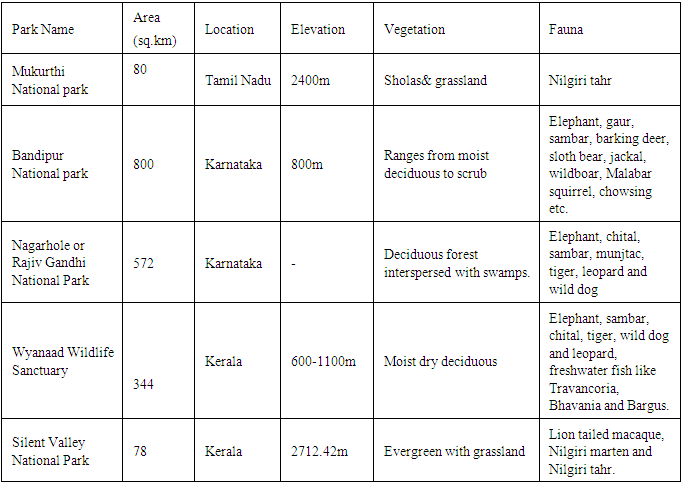

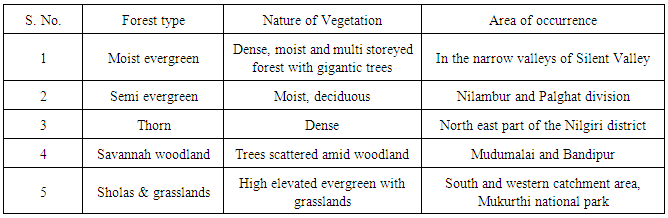

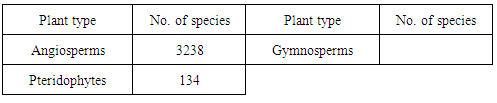

- The UNESCO has introduced the designation ‘Biosphere Reserve’ for natural areas to minimize conflict between development and conservation. Biosphere Reserve are nominated by national government which meet a minimal set of criteria and adhere to minimal set of conditions for inclusion in the world network of Biosphere reserves under the Man and Biosphere Reserve Programme of UNESCO.According to UNESCO, There are total there are 631 biosphere reserves in 119 countries, including 14 Trans boundary sites. They are distributed as follows:a) 64 in 28 countries in Africa b) 27 in 11 countries in the Arab Statesc) 130 in 23 countries in Asia and the Pacificd) 290 in 36 countries in Europe and North Americae) 120 in 21 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.Some facts that decide the feature of Biosphere Reserves:a) An area must contain an effectively protected and minimally disturbed core area for nature conservation. b) The core area should be a bio-geographical unit and large enough to sustain viable populations representing all trophic levels in the ecosystem. c) The management authority to ensure the involvement and cooperation of local communities to bring variety of knowledge and experiences to link biodiversity conservation and socio-economic development while managing and containing the conflicts. d) Areas potential for preservation of traditional tribal and rural modes of living for harmonious use of environment (Mof, 2015)Structure and functions of BR:Biosphere reserves are demarcated into following 3 inter-related zones:Core Zone: Core zone must contain suitable habitat for numerous plant and animal species, including higher order predators and may contain centres of endemism. Core areas often conserve the wild relatives of economic species and also represent important genetic reservoirs having exceptional scientific interest. The core area(s) comprises a strictly protected ecosystem that contributes to the conservation of landscapes, ecosystems, species and genetic variation. A core zone being National Park or Sanctuary/ protected/regulated mostly under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. Whilst realizing that perturbation is an ingredient of ecosystem functioning, the core zone is to be kept free from l human pressures external to the system. Buffer Zone: The buffer zone adjoins or surrounds core zone, uses and activities are managed in this area in the ways that help in protection of core zone in its natural condition. These uses and activities include restoration, demonstration sites for enhancing value addition to the resources, limited recreation, tourism, fishing, grazing, etc. which are permitted to reduce its effect on core zone. Research and educational activities are to be encouraged. Transition Zone: The transition area is the outermost part of a biosphere reserve, includes settlements, crop lands, managed forests and area for intensive recreation and other economic uses characteristics of the region. It is the part of the reserve where the greatest activity is allowed, fostering economic and human development that is socio-culturally and ecologically sustainlabe.Functions of BR: There are main three functions• Conservation• Development and• Logistic support.a) To conserve the diversity and integrity of plants and animals within natural ecosystemsb) To safeguard genetic diversity of species on which their continuing evolution dependsc) To ensure sustainable use of natural resources through most appropriate technology for improvement of economic well-being of the local peopled) To provide areas for multi-faceted research and monitoringe) To provide facilities for education and trainingIndia’s Biosphere Reserves: India’s Biosphere Reserves often include one or more National Parks or sanctuaries along with buffer zones that are open to some economic uses. Protection is granted not only to the flora and fauna of the protected region but also for the human communities who inhabit these regions and their ways of life.Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve: The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve was the first biosphere reserve in India established in the year 1986. It is located in the Western Ghats and includes two of the ten bio geographical provinces of India. A wide range of ecosystems and species diversity is found in this region. Thus, it was a natural choice for the premier biosphere reserve of the country. The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve was established mainly to fulfill the following objectives:a) To conserve insitu genetic diversity of speciesb) To restore degraded ecosystems to their natural conditionsc) To provide baseline data for ecological and environmental research and educationd) To function as an alternate model for sustainable development.

| Figure 1. Objective of a Biosphere Reserve |

|

| Figure 2. Location of Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. Source: UNESCO |

|

|

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML