-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Ecosystem

p-ISSN: 2165-8889 e-ISSN: 2165-8919

2015; 5(2): 44-58

doi:10.5923/j.ije.20150502.02

The Effect of Predator Competition on the Stability of Sea Star - Mussel Population Dynamics

Luis Soto-Ortiz

Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of California, Irvine, California, USA

Correspondence to: Luis Soto-Ortiz, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of California, Irvine, California, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Experimental evidence has shown that the ochre sea star (Pisaster ochraceus) is capable of a developmental response to an increase in mussel biomass. This plasticity of growth allows sea stars to increase in size which, in turn, enhances their mussel feeding rate. A developmental response allows sea stars to stabilize a fast-growing mussel population. This article presents a deterministic model based on energy flow mechanisms that simulates the effect of predator competition for prey on the predatory developmental response. Predator competition was simulated by considering scenarios consisting of different sea star densities. The model predicted that a low sea star density will lead to: 1) a high abundance of mussels regardless of the initial average sea star size, and 2) a large average predator size due to the low competition for prey. The model predicts a significant reduction in average sea star size if sea star density increases, if mussel density is low, or if the mussels are of a small size. These results are consistent with empirical evidence which shows that sea stars can shrink in order to survive in an environment that does not provide the necessary energy to sustain their growth. Bifurcation analysis identified a value of predator density below which sea star-mussel coexistence is possible, and above which mussels can escape predation and their density grows to the carrying capacity of the environment.

Keywords: Developmental response, Pisaster ochraceus, Mathematical modeling, Bifurcation

Cite this paper: Luis Soto-Ortiz, The Effect of Predator Competition on the Stability of Sea Star - Mussel Population Dynamics, International Journal of Ecosystem, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 44-58. doi: 10.5923/j.ije.20150502.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- An early assumption of the theory of rocky shore communities was that there are no stabilizing responses by the ochre sea star (Pisaster ochraceus) on the population of its main prey, the California mussel (Mytilus californianus). Instead, it was believed that physical factors, mainly desiccation stress, kept sea stars from foraging for mussels in a spatial refuge high on the shore [1]. It was thought that the vertical foraging ranges of sea stars were fixed by the tidal regime: the upper shore level being the refuge, or safe zone, for mussels, whereas the lower shore level was considered to be the zone accessible to sea stars. Thus, the assumption was that there is no biotic regulatory interplay based on reciprocal responses between sea stars and mussels, as observed in other predator-prey interactions. Subsequent experiments showed that some mussels were able to escape predation by sea stars, not because of a spatial refuge, but because these mussels grew large enough to resist the predatory activities of sea stars. In 1959, C.S. Holling published a study on the numerical and functional responses exhibited by predators based on prey availability [2]. A numerical response is characterized by an increase in predator density whenever prey density increases. A functional response occurs when a predator kills more prey in response to an increase in prey availability. Holling demonstrated that desert rodents show an increase in density and predation rate in response to an increase in the density of their prey Symphyta (sawfly), thereby keeping the prey from completely populating the local environment. More recent studies suggest that Pisaster may have similar behavioral responses to changes in mussel abundance. A juvenile mussel transplantation experiment [3] demonstrated that Pisaster has the ability to aggregate in areas of high mussel recruitment and disperse in areas of low mussel recruitment, which is suggestive of a numerical regulatory response by sea stars. This aggregative response by sea stars, in addition to an increase in predation rate with an increase in mussel density, a functional response, helps to keep the mussel population in check. Another observation that exemplified the stabilizing regulation by sea stars is that variation in mussel recruitment has the potential to cause huge fluctuations in the lower intertidal zone if no predators were present, but such fluctuations are seldom observed under natural conditions. A predatory response that has been proposed, known as the developmental response, is defined as a predator’s ability to consume more prey in proportion to the size of the predator [4]. A predator that is capable of a developmental response exhibits plasticity of growth. That is, as the predator continues to feed, it will increase in size allowing it to increase its predation rate. A predator that is capable of a developmental response has the ability to change its feeding habits as it grows by eating larger prey, alternate prey, or by an increase in its predation rate. In the case of the sea star/mussel interaction, as a sea star grows, it will increase its predation rate on the mussel population. On the other hand, in the case of very low prey density or very small prey size, a predator that exhibits plasticity of growth will shrink to a small size. Theory predicts that predators that are capable of exhibiting numerical, functional and developmental responses will be able to stabilize a prey population more effectively than predators that only exhibit a subset of these predatory responses [5]. In 1970, Howard Feder conducted experiments to study the plasticity of sea star growth [6] and found that average sea star size in a particular location is related to the abundance and size of prey at that site. A relationship between the size of a sea star and the prey it eats exists because the energy provided by the environment depends on the size and density of prey. Feder demonstrated that a primary reaction of sea stars to starvation is a loss of body mass instead of death. As prey density increases, more energy is available in the environment to sustain sea star growth. To simulate the plasticity of growth of sea stars, an ODE-based model was derived to account for predator competition for prey due to a large predator density or due to low prey density. The model is used to simulate experiments similar to those performed by Landenberger [7] and Menge [8], where dead mussels were continuously replaced with adult mussels of the same size in order to keep the average mussel size and mussel density constant. The model also simulates experiments where average mussel size is kept constant, mussel density is allowed to vary over time, and there is a constant mussel recruitment rate. The derivation of the mathematical model is based on energy flow mechanisms and is presented in the Materials and Methods section. Stability and bifurcation analyses are presented in the Results section, followed by suggestions for improving the model in the Discussion section.

2. Materials and Methods

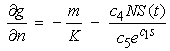

- The individual growth rate of a sea star is based on a balance of the energy flow mechanisms that are known to affect sea star growth. The following assumptions were made to derive the model:1.An open system where the prey recruitment is independent of mussel density and sea stars do not leave the region (mussel patch) regardless of prey density.2.Mussel growth rate and mortality due to natural causes are negligible.3.Sea star size and mussel size are assumed to be the average values of each population.4.New mussel recruits are assumed to be adult mussels of constant size.5.Environmental disturbances affecting predator mortality or foraging activity were not considered.6.It is assumed that competition for prey is negligible when predator density is low, but competition becomes intense at high predator densities.

2.1. Energy Flow Mechanisms in a Sea Star

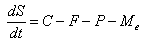

- Field experiments [9] have demonstrated that given a group of keystone predators, a large majority of them will feed when there is prey abundance, but only a small portion will feed during periods of prey scarcity. Rapport and Turner [10] suggested that Pisaster ochraceus is an energy maximizer. That is, this sea star does not feed at its physiological maximum rate but, instead, this species consumes prey at a rate that maximizes its net energy gain. Therefore, energy flow plays a significant role in determining the growth of a sea star. While sea stars obtain energy from the environment by consumption of mussels, they also lose energy through a variety of mechanisms. For example, sea stars use energy while foraging and handling prey and by sustaining metabolic processes. A sea star will grow (increase in diameter) if its net energy gain is sufficient to promote growth. A sea star will shrink in size if the energy loss is greater than its energy gain. Based on previous experimental observations [6-8], [11], energy flow mechanisms provide a sound explanation of the observed growth of sea stars in response to variations in prey biomass (abundance and average size). The net change in sea star size over time due to energy gain or loss can be represented by the following equation

| (1) |

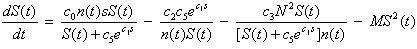

2.2. Modeling the Growth Rate of Sea Stars

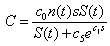

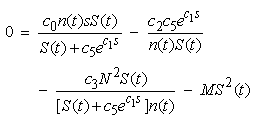

- Energy flow mechanisms affect the net energy gain (or loss) that drives sea star size growth (or shrinkage). The model uses an equation similar to the one described in [10] that incorporates all of these energy mechanisms. Equation 2 models changes in average sea star size over time:

| (2) |

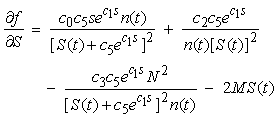

2.2.1. Energy Gain Due to Mussel Consumption

- We let c0 be a coefficient that relates average energy gained by a sea star through consumption of mussels having biomass n(t)s, to individual sea star growth. Mussel resistance to predation increases exponentially with an increase in mussel size s and is represented by the term

[9, 10], where c1 is a coefficient relating mussel resistance to predation to mussel size. The dimensionless factor

[9, 10], where c1 is a coefficient relating mussel resistance to predation to mussel size. The dimensionless factor  represents the predation efficacy of a sea star. The constant c5 is a weighting factor used to adjust the units for dimensional consistency. Since larger sea stars consume more mussels as a consequence of their developmental response, this means that the predation efficacy increases with an increase in sea star size S(t) if mussel size s is kept constant. On the other hand, since an increase in mussel size leads to a higher predation resistance, the predation efficacy of the sea star decreases with an increase in s. The fact that a larger mussel biomass n(t)s provides more calories for sea stars is represented in equation 3, which describes the energy gain of a sea star through mussel consumption

represents the predation efficacy of a sea star. The constant c5 is a weighting factor used to adjust the units for dimensional consistency. Since larger sea stars consume more mussels as a consequence of their developmental response, this means that the predation efficacy increases with an increase in sea star size S(t) if mussel size s is kept constant. On the other hand, since an increase in mussel size leads to a higher predation resistance, the predation efficacy of the sea star decreases with an increase in s. The fact that a larger mussel biomass n(t)s provides more calories for sea stars is represented in equation 3, which describes the energy gain of a sea star through mussel consumption  | (3) |

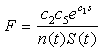

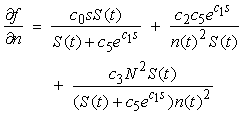

2.2.2. Energy Cost of Foraging and Handling of Prey

- Sea stars spend energy searching for prey and this foraging cost is reduced when mussels are abundant. The smaller the mussel density, the greater the distance sea stars have to travel to search for food items, thus increasing the foraging cost. The expression

represents the inverse relationship between foraging cost and mussel density. The coefficient c2 relates mussel density to energy spent through foraging. In addition, the expression

represents the inverse relationship between foraging cost and mussel density. The coefficient c2 relates mussel density to energy spent through foraging. In addition, the expression | (4) |

| (5) |

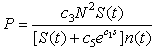

2.2.3. Energy Cost Due to Competition for Prey

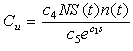

- Whenever sea stars share a common resource, they will compete directly for food via intraspecific or interspecific agonistic behavior [13, 14], or will compete indirectly by depriving their competitors of food items [8]. A large group of sea stars equipped with a good predation efficacy may reduce or deplete food items in a particular region, which leads to an increased search time for other sea stars due to the fact that they now have to forage farther out to find suitable prey. Therefore, the energy cost due to competition between predators increases as the predation efficacy

increases.Mussel density n(t) influences the energy cost by sea stars due to competition for prey, since mussel density determines food availability in the environment and affects the foraging time of sea stars. A quadratic term N2 was used to model the assumption that competition for prey is negligible when predator density is low, but becomes very intense at high predator densities. The expression for the total energy cost due to competition for prey is given by

increases.Mussel density n(t) influences the energy cost by sea stars due to competition for prey, since mussel density determines food availability in the environment and affects the foraging time of sea stars. A quadratic term N2 was used to model the assumption that competition for prey is negligible when predator density is low, but becomes very intense at high predator densities. The expression for the total energy cost due to competition for prey is given by | (6) |

2.2.4. Energy Cost Due to Metabolic Processes

- If one assumes that the energy cost due to metabolism Me is proportional to the surface area of a sea star, and represent its surface area by S2(t), then a larger sea star will spend more calories per unit time to sustain metabolic processes. This assumption is represented by the equation

| (7) |

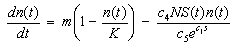

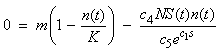

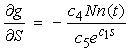

2.3. Changes in Mussel Density

- Sea stars experience a growth or reduction in size in response to changes in prey biomass n(t)s. Under natural conditions, mussel biomass varies in the intertidal zone according to gradients that include mussel recruitment rate, tidal height, and wave stress. In the model, mussel density n(t) was allowed to vary over time, and changes in mussel density over time

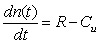

were incorporated in the model to account for the variability of mussel biomass in naturally-occurring mussel beds. A density-dependent logistic growth model for mussel population growth was considered as described in [15]. The mussel population growth rate R tends toward zero when mussel density n(t) approaches the maximum carrying capacity K = 400 mussels / m2 of the environment. The mussel population growth rate is high when mussel density is low. The rate of change of the mussel population depends on a balance between mussel growth rate R and the mussel consumption rate Cu by sea stars. The rate of change of the mussel population is represented by the equation

were incorporated in the model to account for the variability of mussel biomass in naturally-occurring mussel beds. A density-dependent logistic growth model for mussel population growth was considered as described in [15]. The mussel population growth rate R tends toward zero when mussel density n(t) approaches the maximum carrying capacity K = 400 mussels / m2 of the environment. The mussel population growth rate is high when mussel density is low. The rate of change of the mussel population depends on a balance between mussel growth rate R and the mussel consumption rate Cu by sea stars. The rate of change of the mussel population is represented by the equation | (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

3. Results

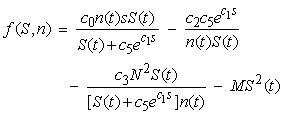

3.1. Graphical Stability Analysis

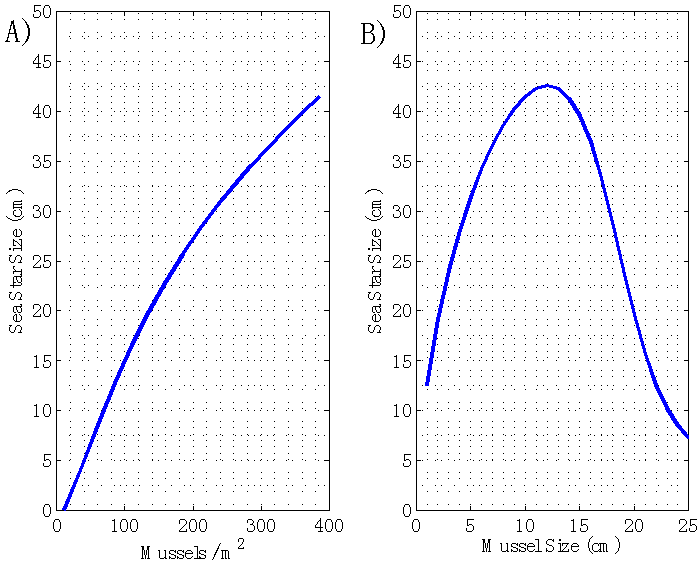

- In Cases 1 – 3, prey density was kept constant at the environmental carrying capacity of 400 mussels / m2. It was assumed that all the mussels have the same size and that a mussel that is killed by a sea star is immediately replaced with an adult mussel of the same size. By holding prey density constant, the effect that a change in predator density N has on the terminal size of sea stars was investigated. The parameter values used in the model simulations are listed in Table 1 and were estimated based on empirical evidence.

| (11) |

| (12) |

|

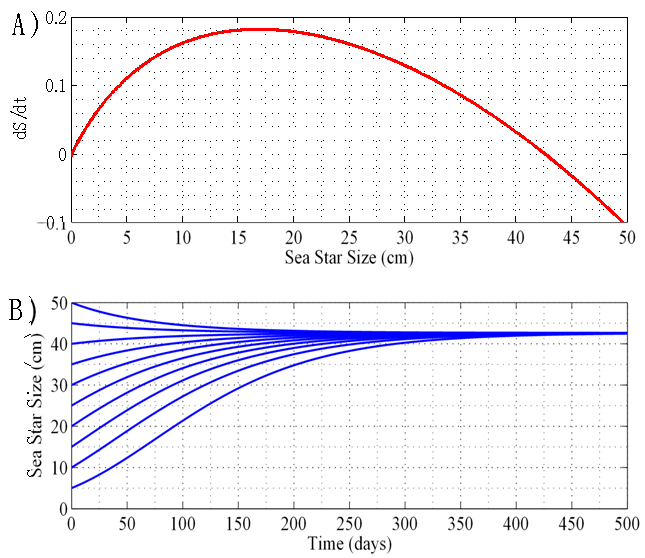

3.1.1. Case 1: N = 1 sea star / m2

- By holding sea star density constant at N = 1 sea star / m2, the model predicted an asymptotically stable equilibrium for average sea star diameter of 42.7 cm, and an unstable equilibrium of

cm. This prediction is shown in the plot of growth rate dS/dt versus size S in Figure 1A, and in the plot of size S versus time t shown in Figure 1B. In terms of energy flow mechanisms, this environment does not lead to a net energy gain that is sufficient for sea stars to grow beyond 42.7 cm. Sea stars with an initial size larger than 42.7 cm will adapt to environmental conditions by shrinking. The model predicts that very small sea stars will have a hard time killing mussels and, consequently, it will take them much longer to grow and reach the stable equilibrium size of 42.7 cm. Although such a large sea star size is not common in nature, sea stars of a comparable size have been observed [16]. A large predicted terminal sea star size is plausible in this simulated environment, given that it consists of a high mussel density and competition between sea stars is negligible due to the low predator density. The sea stars don’t need to forage at all to find their prey due to the high mussel density. In this scenario, mussels 10 cm long are a significant source of energy and the prey handling cost incurred by the sea stars is not excessively high.

cm. This prediction is shown in the plot of growth rate dS/dt versus size S in Figure 1A, and in the plot of size S versus time t shown in Figure 1B. In terms of energy flow mechanisms, this environment does not lead to a net energy gain that is sufficient for sea stars to grow beyond 42.7 cm. Sea stars with an initial size larger than 42.7 cm will adapt to environmental conditions by shrinking. The model predicts that very small sea stars will have a hard time killing mussels and, consequently, it will take them much longer to grow and reach the stable equilibrium size of 42.7 cm. Although such a large sea star size is not common in nature, sea stars of a comparable size have been observed [16]. A large predicted terminal sea star size is plausible in this simulated environment, given that it consists of a high mussel density and competition between sea stars is negligible due to the low predator density. The sea stars don’t need to forage at all to find their prey due to the high mussel density. In this scenario, mussels 10 cm long are a significant source of energy and the prey handling cost incurred by the sea stars is not excessively high.3.1.2. Case 2: N = 8 sea stars / m2

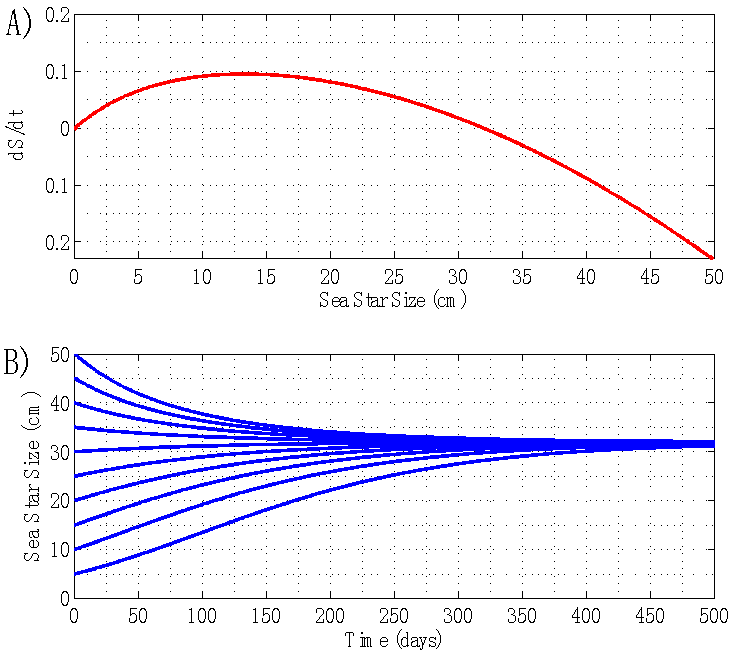

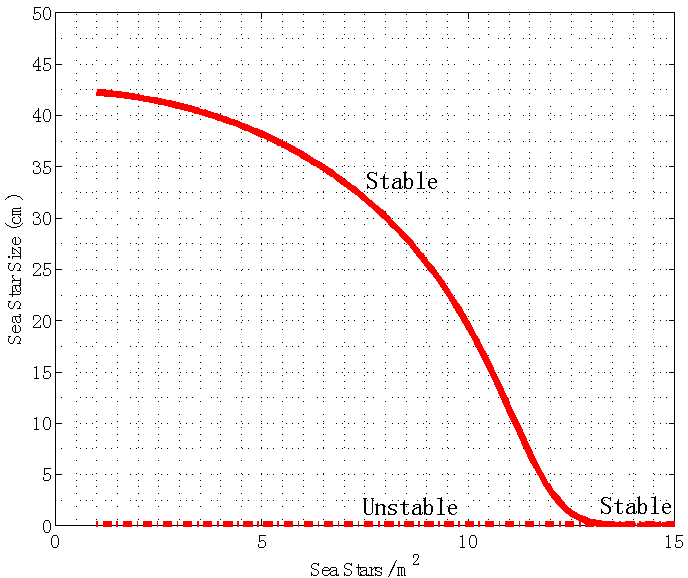

- In this scenario, sea star density was increased to N = 8 sea stars / m2. The model predicted a sea star diameter of S = 32 cm to be asymptotically stable and S = 0 cm to be unstable. This prediction is shown in the plot of growth rate dS/dt versus size S in Figure 2A, and in the plot of size S versus time t shown in Figure 2B. These results indicate that an environment characterized by a constant large supply of mussels having a size of 10 cm, can support a relatively large sea star density of N = 8 sea stars / m2. In this scenario, competition for prey increased considerably, leading to a smaller average sea star size due to the cost of intraspecific competition. The predicted terminal size of 32 cm, although smaller than the sea star size predicted in Case 1, was still relatively large. This result can be attributed to the fact that in Case 2 sea stars were surrounded by a dense bed of mussels and, thus, did not have to spend much time looking for prey.Since the stable equilibrium value for average sea star size decreased with an increase in sea star density from N = 1 to N = 8, it is expected that the stable equilibrium value for S will approach the unstable one (

cm) as the predator density N is increased, since no environment can support an infinite number of sea stars due to predator interference and competition for prey. There must exist a predator density Nb such that the predators and prey will be unable to coexist if

cm) as the predator density N is increased, since no environment can support an infinite number of sea stars due to predator interference and competition for prey. There must exist a predator density Nb such that the predators and prey will be unable to coexist if  i.e. sea starts will shrink to a size so small that they will no longer be able to prey effectively on mussels and would no longer be considered predators of mussels. An objective of the stability analysis was to identify the value Nb that produces the predicted bifurcation.

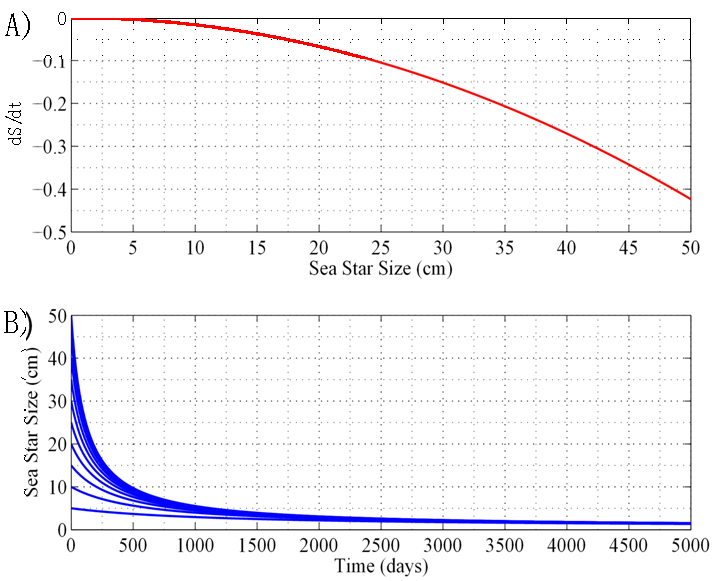

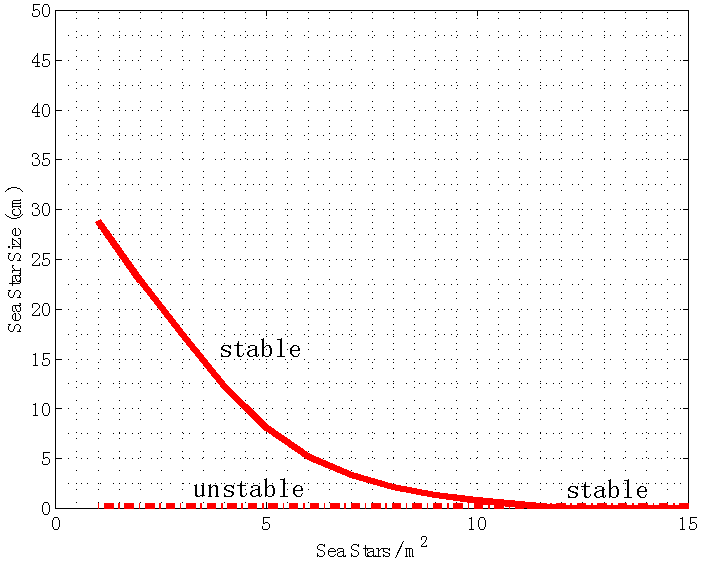

i.e. sea starts will shrink to a size so small that they will no longer be able to prey effectively on mussels and would no longer be considered predators of mussels. An objective of the stability analysis was to identify the value Nb that produces the predicted bifurcation.3.1.3. Case 3: N = 12.62 sea stars / m2

- When sea star density was increased to 12.62 sea stars / m2, the system underwent a bifurcation characterized by a coalescence of the stable and unstable equilibrium points. The plot of growth rate dS/dt versus size S in Figure 3A shows that the curve fails to intersect the positive side of the x-axis. The consequence of this bifurcation is that if

sea stars / m2, sea stars of any size will decrease in diameter (Figure 3B) and their long-term size will approach zero (a globally stable equilibrium). The fact that sea star size tends toward zero does not necessarily mean that the sea stars will die. Experimental observations have shown that sea stars can survive without food for months [6]. The model predicts that sea stars survive by shrinking to reduce metabolic costs, while sacrificing their mussel predation efficacy. Tiny sea stars are no longer considered predators of mussels and, at this point, predator-prey coexistence disappears. Based on the predictions of the model, a predator density of 12.62 sea stars / m2 is too large for the specified environmental conditions of this scenario to be a source of net energy gain for a sea star of any size. In nature, it is possible that when average sea star size is large and sea star density is high, agonistic behavior will occur between sea stars. These combative actions may lead sea stars to experience a high energy cost due to competition for prey. Eventually, these sea stars will shrink to a size so small that they will be unable to prey on the mussels and will shrink even further, thus explaining why

sea stars / m2, sea stars of any size will decrease in diameter (Figure 3B) and their long-term size will approach zero (a globally stable equilibrium). The fact that sea star size tends toward zero does not necessarily mean that the sea stars will die. Experimental observations have shown that sea stars can survive without food for months [6]. The model predicts that sea stars survive by shrinking to reduce metabolic costs, while sacrificing their mussel predation efficacy. Tiny sea stars are no longer considered predators of mussels and, at this point, predator-prey coexistence disappears. Based on the predictions of the model, a predator density of 12.62 sea stars / m2 is too large for the specified environmental conditions of this scenario to be a source of net energy gain for a sea star of any size. In nature, it is possible that when average sea star size is large and sea star density is high, agonistic behavior will occur between sea stars. These combative actions may lead sea stars to experience a high energy cost due to competition for prey. Eventually, these sea stars will shrink to a size so small that they will be unable to prey on the mussels and will shrink even further, thus explaining why  cm became an asymptotically stable equilibrium point.

cm became an asymptotically stable equilibrium point. . The two equilibria coalesce when N = 12.62 sea stars / m2. For N > 12.62 sea stars / m2 the only stable equilibrium is

. The two equilibria coalesce when N = 12.62 sea stars / m2. For N > 12.62 sea stars / m2 the only stable equilibrium is  . This means that, given a very large sea star density, sea stars will shrink to a small size due to their energy being spent on agonistic behavior against each other, as well as intraspecific competition for mussels. Once sea stars shrink to a very small size, they will no longer be able to kill adult mussels and the sea stars will remain small.

. This means that, given a very large sea star density, sea stars will shrink to a small size due to their energy being spent on agonistic behavior against each other, as well as intraspecific competition for mussels. Once sea stars shrink to a very small size, they will no longer be able to kill adult mussels and the sea stars will remain small.3.1.4. Case 4: N = 1 sea star / m2

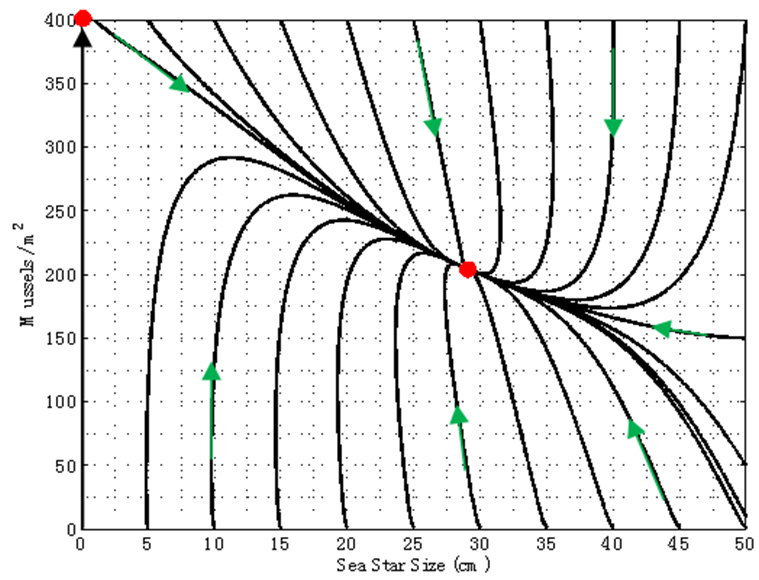

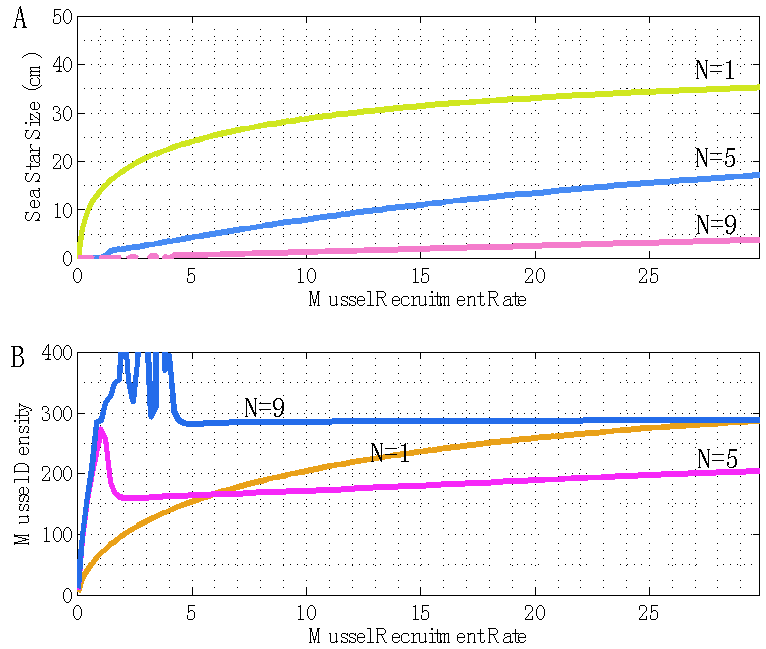

- When sea star density was fixed at N = 1 sea star / m2 and mussel density was allowed to vary, two equilibrium points were obtained, one stable and the other unstable. A phase portrait of mussel density n(t) versus sea star diameter S(t) is shown in Figure 6, where both n(t) and S(t) represent dynamical variables specifying the state of the predator-prey system at time t. Trajectories that flow towards the stable equilibrium (asymptotically stable node) show that, given the environment specified by the parameter values, sea stars and mussels can coexist, with sea stars predicted to have a terminal size of 28.8 cm in diameter, while the mussel population will reach an asymptotic density of 205.6 mussels / m2. The unstable equilibrium (saddle) occurs when

cm, which means that no sea stars capable of preying on mussels are present, allowing mussel density to approach the carrying capacity of 400 mussels / m2. In Figure 6, the vertical trajectory going up along the vertical n-axis is a branch of the stable manifold of the saddle point (S*, n*) = (0 cm, 400 mussels / m2), and it confirms the fact that in the absence of a keystone predator such as the ochre sea star, mussels are able to colonize the entire substrate and are capable of excluding other species from the area.

cm, which means that no sea stars capable of preying on mussels are present, allowing mussel density to approach the carrying capacity of 400 mussels / m2. In Figure 6, the vertical trajectory going up along the vertical n-axis is a branch of the stable manifold of the saddle point (S*, n*) = (0 cm, 400 mussels / m2), and it confirms the fact that in the absence of a keystone predator such as the ochre sea star, mussels are able to colonize the entire substrate and are capable of excluding other species from the area.3.1.5. Case 5: N = 5 sea stars / m2

- In this scenario, predator density was increased to N = 5 sea stars / m2. Figure 7 shows that sea stars and mussels can still coexist in spite of the increased sea star competition for mussels. The model predicts an average terminal sea star size of 8 cm and a smaller mussel density of 172.5 mussels / m2, thus simulating the regulatory effect of sea stars on the mussel population. Large sea stars will shrink due to increased competition, and the faster depletion of prey due to the developmental response of large sea stars. The trajectories shown in the phase portrait illustrates the capability of sea stars of growing, or shrinking, to a size that will maximize their net energy gain while still allowing them to keep the mussel density in check. The unstable equilibrium (saddle) corresponds to an average sea star size of

cm (no sea stars capable of preying on mussels are present), in which case mussel density will increase to the carrying capacity along the stable manifold of the saddle point.

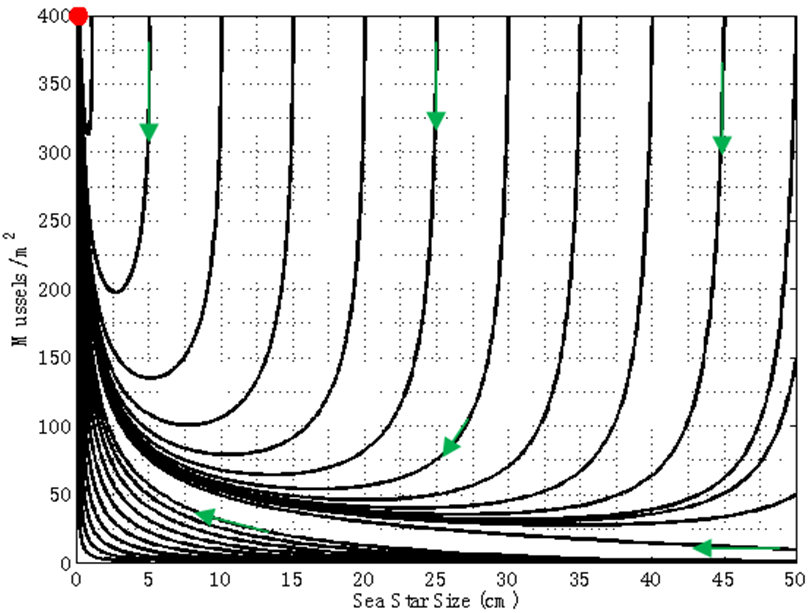

cm (no sea stars capable of preying on mussels are present), in which case mussel density will increase to the carrying capacity along the stable manifold of the saddle point.3.1.6. Case 6: N = 11.68 sea stars / m2

- Increasing predator density to N = 11.68 sea stars / m2 produced a bifurcation of the equilibrium points into a single globally stable equilibrium point (S*, n*) = (0 cm, 400 mussels / m2). The decrease in average sea star size to

cm is due to intraspecific competition for prey. The trajectories of the phase portrait in Figure 8 show that as mussel density decreases, sea stars experience an increase in predation cost due to competition for prey. This energy cost outweighs any energy gains made by sea stars while foraging, and will result in a net reduction in average sea star size to a very small size

cm is due to intraspecific competition for prey. The trajectories of the phase portrait in Figure 8 show that as mussel density decreases, sea stars experience an increase in predation cost due to competition for prey. This energy cost outweighs any energy gains made by sea stars while foraging, and will result in a net reduction in average sea star size to a very small size  cm. Consequently, there will be an increase in mussel density up to the mussel carrying capacity. A group of sea stars that is initially large is able to reduce mussel density to a greater extent than a group of small sea stars. In both cases sea star size approaches zero due in part to competition for prey when sea stars are large, and due to small sea stars being unable to prey on mussels that are 10 cm long.

cm. Consequently, there will be an increase in mussel density up to the mussel carrying capacity. A group of sea stars that is initially large is able to reduce mussel density to a greater extent than a group of small sea stars. In both cases sea star size approaches zero due in part to competition for prey when sea stars are large, and due to small sea stars being unable to prey on mussels that are 10 cm long. cm. At N = 11.68 the two equilibria coalesce. For N > 11.68 the only stable equilibrium is

cm. At N = 11.68 the two equilibria coalesce. For N > 11.68 the only stable equilibrium is  cm, in which case sea stars of any size will shrink to reduce the direct competition for prey, and to decrease the metabolic cost incurred when a sea star has a large body size. In an actual intertidal setting, tiny sea stars may feed on alternate prey or stop foraging altogether and remain small.

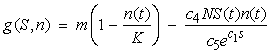

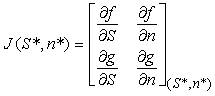

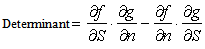

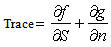

cm, in which case sea stars of any size will shrink to reduce the direct competition for prey, and to decrease the metabolic cost incurred when a sea star has a large body size. In an actual intertidal setting, tiny sea stars may feed on alternate prey or stop foraging altogether and remain small.3.2. Analytical Stability Analysis

- An analytical stability analysis was conducted to verify the results of Cases 4 – 6. The equilibrium points (S*, n*) were computed by setting

and

and  in equations (11) and (12) and solving the following system of nonlinear algebraic equations for S(t) and n(t) simultaneously:

in equations (11) and (12) and solving the following system of nonlinear algebraic equations for S(t) and n(t) simultaneously: | (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

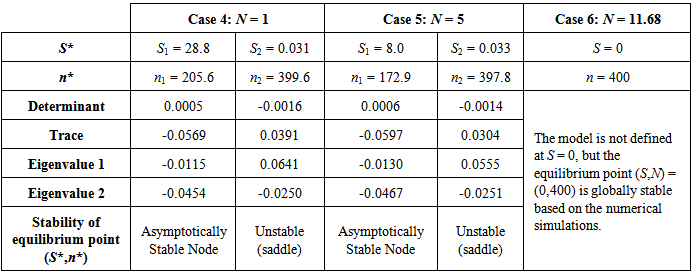

(S2, n2) = (0.031, 399.6)

(S2, n2) = (0.031, 399.6) Case 5: N = 5 sea stars / m2(S1, n1) = (8.0, 172.9)

Case 5: N = 5 sea stars / m2(S1, n1) = (8.0, 172.9) (S2, n2) = (0.033, 397.8)

(S2, n2) = (0.033, 397.8) Case 6: N = 11.68 sea stars / m2(S, n ) = (0, 400)

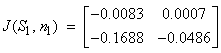

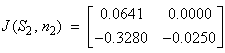

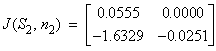

Case 6: N = 11.68 sea stars / m2(S, n ) = (0, 400) Table 2 shows that when sea star density equals 1 sea star / m2 and mussel density is allowed to vary over time (Case 4), the equilibrium point (S1, n1) = (28.8 cm, 205.6 mussels/m2) in Figure 6 is an asymptotically stable node, since the determinant is positive and both eigenvalues are real negative numbers. This stable equilibrium point represents coexistence of predator and prey. The equilibrium point (S2, n2) = (0.031 cm, 399.6 mussels/m2) is a saddle because the determinant is negative. This means that in nature, mussel density will approach the environmental carrying capacity via the stable manifold (the n-axis) in the absence of predatory sea stars, or in the presence of sea stars that are too small to kill any mussels. A small perturbation about the point (0.031 cm, 399.6 mussels/m2) represented by the presence of predatory sea stars, will reduce the mussel density to the asymptotic value of 205.6 mussels / m2. In Case 5, when sea star density was fixed at 5 sea stars / m2 and mussel density is allowed to vary over time, the equilibrium point (S1, n1) = (8.0 cm, 172.9 mussels/m2) in Figure 7 is an asymptotically stable node because both eigenvalues are real, negative numbers. On the other hand, the equilibrium point (S2, n2) = (0.033 cm, 397.8 mussels/m2) is unstable.

Table 2 shows that when sea star density equals 1 sea star / m2 and mussel density is allowed to vary over time (Case 4), the equilibrium point (S1, n1) = (28.8 cm, 205.6 mussels/m2) in Figure 6 is an asymptotically stable node, since the determinant is positive and both eigenvalues are real negative numbers. This stable equilibrium point represents coexistence of predator and prey. The equilibrium point (S2, n2) = (0.031 cm, 399.6 mussels/m2) is a saddle because the determinant is negative. This means that in nature, mussel density will approach the environmental carrying capacity via the stable manifold (the n-axis) in the absence of predatory sea stars, or in the presence of sea stars that are too small to kill any mussels. A small perturbation about the point (0.031 cm, 399.6 mussels/m2) represented by the presence of predatory sea stars, will reduce the mussel density to the asymptotic value of 205.6 mussels / m2. In Case 5, when sea star density was fixed at 5 sea stars / m2 and mussel density is allowed to vary over time, the equilibrium point (S1, n1) = (8.0 cm, 172.9 mussels/m2) in Figure 7 is an asymptotically stable node because both eigenvalues are real, negative numbers. On the other hand, the equilibrium point (S2, n2) = (0.033 cm, 397.8 mussels/m2) is unstable.

|

as

as  and the average sea star size will become so small that these tiny sea stars will be unable to prey on mussels. This, in turn, leads to an asymptotic mussel density of 400 mussels / m2. Based on the results of the graphical and analytical stability analyses, the model predictions correspond to what is expected to occur in nature.

and the average sea star size will become so small that these tiny sea stars will be unable to prey on mussels. This, in turn, leads to an asymptotic mussel density of 400 mussels / m2. Based on the results of the graphical and analytical stability analyses, the model predictions correspond to what is expected to occur in nature.4. Discussion

- The analysis of the model presented in this article yielded information on conditions leading to predator-prey coexistence when the predator is capable of a developmental response to changes in prey density. It was also shown that the stabilizing effect of an increase in sea star density N is possible only for a particular N range. However, the stabilizing effect of sea stars on the mussel population can persist in spite of a very large density, if characteristics of the mussel population change (e.g an increase in average mussel size). The key factor that seems to determine coexistence is whether a keystone predator such as Pisaster ochraceus can obtain sufficient energy from the mussel biomass to achieve a terminal size that will allow it to kill prey efficiently. The availability of energy in the environment changes over time whenever mussel recruitment, mussel density or mussel size change. Since the present model assumed a constant mussel recruitment rate m and a constant mussel size s, it will be useful to reformulate the model by redefining these constant parameters as variables of the model. This modification to the model will lead to a more realistic prediction of the changes in mussel biomass n(t)s(t) and average sea star size S(t) over time. Although three different responses by sea stars to changes in mussel biomass are possible (numerical, functional and developmental), the analysis of this model focused only on how predator competition for prey affects the developmental response and the resulting system dynamics. Introducing an equation that simulates the change over time of the predator population P(t) will make it possible to investigate the effect of a numerical response by predators on the stability of predator-prey dynamics. Keeping track of changes in mussel killing rates by sea stars will make it possible to study the effect of a functional response on the sea star - mussel interaction. The objective of future work will be to incorporate the three predatory responses to simulate their synergistic effect, as has been done in [5], to determine the conditions under which this synergism of predatory responses can overcome, or can contribute to, the destabilizing effect of predator competition for prey.Mussel populations are affected by stochastic fluctuations in mussel recruitment [18] and environmental effects that lead to dislodgement of mussels from a patch [19, 20]. Cooperative aggregation and anti-predator defenses by mussels also play a role on the stability of mussel beds [21, 22]. The ODE model presented in this article did not consider these aspects of the mussel population. A stochastic model that considers spatial neighborhood effects could be formulated to incorporate key aspects of mussel population dynamics together with spatial predator foraging and competition for prey. The stochastic model can then be used to investigate the extent to which mussel intraspecific cooperativity can lead to stable predator-prey coexistence, and the extent to which stochastic recruitment can destabilize sea star-mussel interactions.

5. Conclusions

- A deterministic model of sea star growth based on energy flow mechanisms predicted the asymptotic average sea star size as a function of sea star density, mussel recruitment rate and mussel size. These parameters determined the intensity of competition that predators experience and the energy (via prey biomass) available in the environment. The graphical and analytical stability analyses confirmed the existence of an asymptotically stable equilibrium for sea star size and mussel density in which both predator and prey can coexist, demonstrating the capability of a stabilizing response by sea stars. The predictions of this model were consistent with experimental evidence showing that predatory sea stars have the capability of a developmental response, characterized by an increase in feeding rate, as a result of an increase in size, which allows them to stabilize a mussel population. The model also predicted that intense competition for prey between sea stars can hinder their developmental response to the point of rendering them unable to control a mussel population. A bifurcation value for predator density was identified, below which the system exhibits multiple equilibria and predator-prey coexistence is possible, and above which the system exhibits a single equilibrium point that is globally stable. In the latter scenario, predator-prey coexistence disappears, with mussels populating the entire substrate and attaining a density equal to the environmental carrying capacity.

Conflict of Interests

- The author declares that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this article.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML