Etefa Guyassa , Antony Joseph Raj , Kidane Gidey , Alemayehu Tadesse

Department of Land Resource Management and Environmental Protection, College of Dryland Agriculture and Natural Resources, P.O. Box 231, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Antony Joseph Raj , Department of Land Resource Management and Environmental Protection, College of Dryland Agriculture and Natural Resources, P.O. Box 231, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Foods from wild or farmland trees/shrubs in drylands constitute an important component of food supply in the form of fruits, seeds and other edible parts which are essential for food security. Indigenous trees/shrubs are good source of fodder as grasses dry out quickly due to short rainy season. The domestication of important indigenous trees/shrubs (fruits and fodder species) and their integration in agroforestry practices have been one of the most important forms of biodiversity conservation. The selection, retention or deliberate planting and management of trees by farmers can be considered as the beginning of the domestication process of the species. The study was carried out in Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia to assess the domestication process of indigenous fruit and fodder trees/shrubs and to analyze their potential in contribution to food security. Line transect method was employed and systematically laid plots along transects were used to make an inventory of trees in cropland, pasture and backyards. The diversity and population of fruit and fodder species in forests were assessed for comparison with data collected from the agricultural landscapes. The species diversity (richness and evenness) was estimated using different biodiversity indices. The results showed that forest sites have highest fruit and fodder tree/shrub species diversity as compared to other land uses which suggest that domestication process of fruit and fodder trees has been slow with focus on only few trees. A focused questionnaire survey revealed that Opuntia ficus-indica, Ziziphus spina-christi, Mimusops kummel and Prunus persica are the species intentionally retained/planted for their fruit while Faidherbia albida, Acacia nilotica, Ziziphus spina-christi and Becium grandiflorum are maintained for their fodder.

Keywords:

Domestication, Food security, Biodiversity, Species diversity, Agroforestry

Cite this paper: Etefa Guyassa , Antony Joseph Raj , Kidane Gidey , Alemayehu Tadesse , Domestication of Indigenous Fruit and Fodder Trees/Shrubs in Dryland Agroforestry and Its Implication on Food Security, International Journal of Ecosystem, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 83-88. doi: 10.5923/j.ije.20140402.06.

1. Introduction

In dryland areas, there is a frequent failure of agricultural crops and grasses due to low rainfall and lack of moisture. Indigenous trees and shrubs which yield fruit and fodder are an alternative that can support the livelihood of the people. Food from wild or farmland trees/shrubs in drylands constitutes an important component of food supply which is essential for food security. Trees and shrubs contribute to food security directly in the form of fruits, seeds and other edible parts or indirectly by maintaining and restoring soil fertility and water resource which subsequently increase agricultural production [1]. Indigenous trees/shrubs are good source of fodder in dryland areas as grasses dry out in a short period of time due to short rainy season [2]. There are many indigenous trees and shrubs that could be integrated into dryland farming system in dryland regions to support income and nutritional security [3]. Despite the variety, importance and richness of foods from indigenous trees and shrubs in Africa, progress has been very slow in designing and implementing measures to increase the contribution of wild plants to food production and food security [1]. Several investigations indicated that most of the indigenous fruits in Africa are harvested from wild sources (forest, woodland, riverine) [3-4]. Tree domestication is the naturalization or cultivation of tree species to improve their use by people that involves selection of desired trees or genes and converting those trees or genes into the growing trees, which are harvested as a renewable resource [5]. Domesticating agroforestry trees involves accelerated and human-induced evolution to bring species into wider cultivation through a farmer-driven or market-led process.In 1992, modern agriculture’s rejection of the traditionally important tree species was recognized by a most significant IUFRO conference held in 1992 “Tropical trees: The Potential for Domestication and the Rebuilding of Forest Resources” at Edinburgh, UK [6]. Out of that meeting came a global research initiative to domesticate some important tree species as new cash crops for poor, smallholder farmers in the tropics. The initiative was led by the International Centre for Research in Agroforestry (now known as the World Agroforestry Centre) and the tree domestication program (TDP) was begun in 1995 [7]. This programme aimed at improving the quality and yield of products from traditionally important species that used to be gathered from forests and woodlands. In addition to meeting the everyday needs of local people, these products are widely traded in local and regional markets. Underutilized crops and trees therefore have the potential to become new cash crops for income generation and to counter malnutrition and disease by diversifying staple food/ food energy sources and dietary uptake of micro-nutrients that boost the immune system among others. These indigenous tree species also play an important role in enhancing agro-ecological functions and can help to counter climate change through carbon sequestration.The domestication of important indigenous trees/shrubs (fruits and fodder species) and integration in agroforestry system have several benefits beside their food and fodder supply. However, studies on the domestication process (the species locally selected, the level of domestication) of the indigenous fruit and fodder tree/shrub species are lacking in Tigray region of Ethiopia specifically in the study area. The overall objective of this study is to assess domestication process of indigenous fruit and fodder trees/shrubs species and to analyze their potential in contribution to food security. The result of this study will provide a baseline data and records for researchers to conduct a further study on the site requirements, genetic variability, propagation methods, nutritional properties and utilization, and commercial potential of the species. As this study helps to indicate the potential of fruit and fodder trees/shrubs in the contribution of food security, it lays a foundation for foresters and food security organization to take action in the conservation and production of the species; promote local people in the management and utilization of the species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site Description

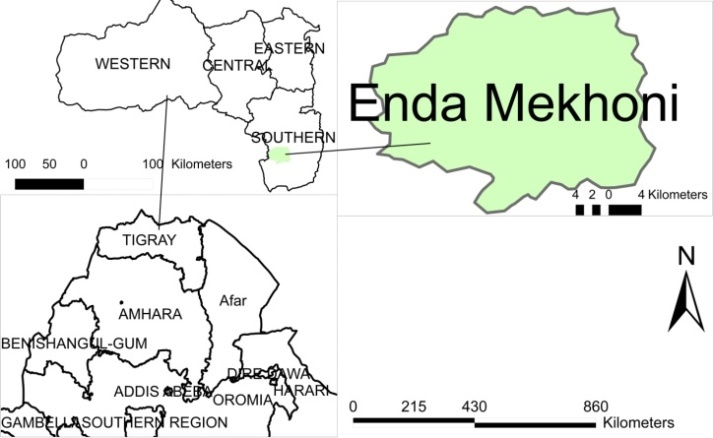

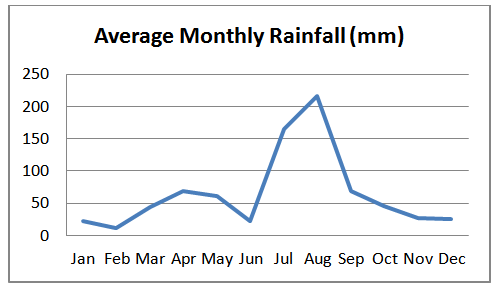

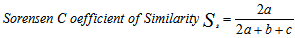

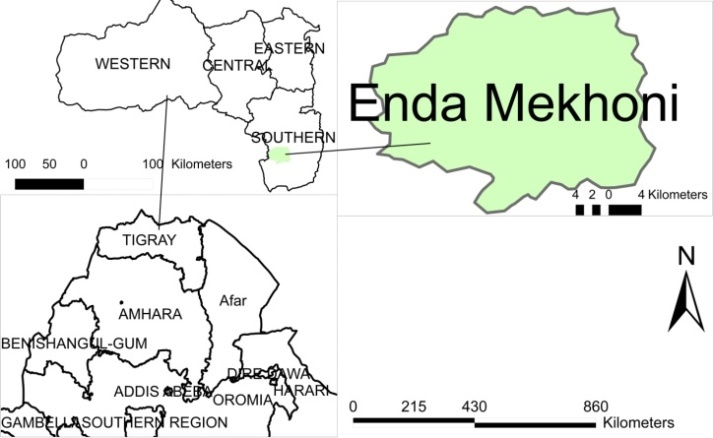

The study was carried out at Enda Mekhoni Woreda, southern zone of Tigray region, northern Ethiopia (Fig.1). The site was selected based on frequent occurrence of drought in the area. The study area is geographically located between latitude 12042’13” to 12046’21’’ N and longitude 39030’20’’ to 39038’47’’ E and at an elevation ranging from 1200 to 1800 masl. The mean minimum and maximum annual rain fall of the study area are 642 and 987 mm, respectively. The rainfall of the area is bimodal with the small rain (short rain season) occurs mainly between March to May, and main rain (long rain season) covering the whole area and occurs from June to September (Fig.2). This pattern, however, is extremely variable with sometime of no rain fall during the short rain fall season. | Figure 1. Study Site: Enda Mekhoni Wordea, Tigray Region, North Ethiopia |

| Figure 2. Average Monthly Rainfall (mm) of Study Area in the past 20 Years |

2.2. Sampling

Two-stage sampling was used to select the sample households, forest land use and agricultural land use. First two adjacent Tabias were purposely selected from a total of 22 available Tabias in the woreda due to availability of forest land use adjacent to agricultural land uses in the Tabias. The Tabias are: Genet and Tsiga’a. In the next stage, households and plots of agricultural land uses and forest land uses were sampled.

2.3. Fruit and Fodder Tree/ Shrub Species Assessments

An inventory was carried out in different landscapes to assess the indigenous fruit and fodder tree/ shrub species diversity and their population. Transect lines were laid out in the Tabias to assess the fruit and fodder tree/shrub species growing on cropland, and backyards (homegarden). Three transect line with 1 km interval were laid out in which 20 plots of cropland and 16 plots of homegardens were used along transects. On average, the size of each cropland plot was 440 m2 while each homegarden plot was 240 m2. The diversity and population of fruit and fodder tree/ shrub species in forests were assessed for comparison with data collected from the agricultural landscapes. The forests used in this study are patch of forests found around church, along rivers, and exclosures. Data was collected from 22 plots of 100 m2 size in forest land that was systematically laid out along transects. The distance between the sample plots and transect lines were 150 m apart (exclosure). Species whose fruits are edible and those consumed by animals were identified by local people (key informants) and recorded. It is less likely to get woody species from small plots of agricultural land uses of similar size as that of the natural forest. Similar approach was also adopted by Nikiema [8] for the comparison of woody species diversity between crop fields and protected forest in Burkina Faso. Most species were identified in the field. When identification was difficult in the field, vernacular names were recorded and identification was carried out using literatures. Nomenclature follows Flora of Ethiopia (Volume 3, 4 part 1, and volume 5). The vernacular name was used in cases where it was difficult to identify the species.

2.4. Tree and Shrub Diversity

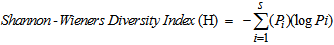

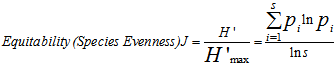

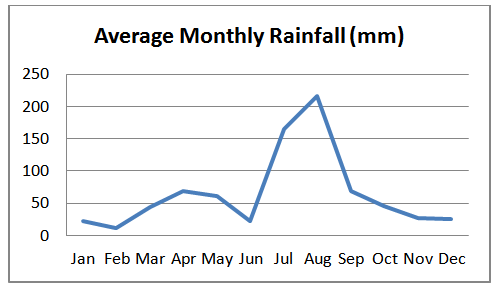

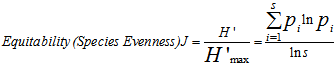

The species diversity (richness and evenness) was estimated using different indices: species richness(S), Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index (H), and equitability index. Species richness is the total number of species in the community [9]. This index does not indicate the relative proportion or abundance of a particular species on the farm. Therefore, the Shannon-Wiener Diversity index [10] and Measure of Evenness (J) were used. | (1) |

Where, s = number of species; Pi = proportion of species i in the communityUsually, Shannon diversity index place most weight on the rare species in the sample [9]. It is also moderately sensitive to sample sizes [11]. Values of the diversity index (H) usually lie between 1.5 and 3.5, although in exceptional cases, the value can exceed 4.5 [12]. Although as a heterogeneity measure, Shannon diversity indices take into account the evenness of abundance of species, it is possible to calculate a separate additional measure of evenness. The ratio of observed Shannon index to maximum diversity (Hmax = ln S) can be taken as a measure of evenness (J) [9], [11-12]. | (2) |

Where S = Number of species found when all sample plots are pooledThe higher the value of J, the more even the species is in their distribution within the sample [12].

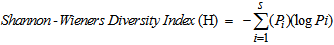

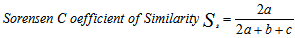

2.5. Similarity Index

Similarity indices measure the degree to which the species composition of different systems is alike. Sorensen similarity coefficient is applied to qualitative data and is widely used because it gives more weight to the species that are common to the samples rather than to those that only occur in either sample [12].  | (3) |

Where a = number of species common to both samples, b = number of species in sample 1, c = number of species in sample 2, The coefficient is multiplied by 100 to give a percentage.

2.6. Socio-Economic Survey

A focused questionnaire survey was administered to a sample of randomly selected 60 senior people (age ≥ 45) from the Tabias comprising 53 males and 7 females. The aim of the interview with older people is to obtain feasible and primary data on the uses, collectors, consumers, time of collection, and the most widely used species and the managements of the species for indigenous fruit and fodder tree/shrub species. Data from socio-economic survey were interpreted, synthesized and presented in Tables and Figures.

3. Results

3.1. Fruit and Fodder Trees/Shrub Species Diversity

In the study area, a total of 35 indigenous fruit and fodder trees/shrub species were identified representing 18 families in which 2 species are only used as most common edible fruits while 11 species are used for animal feed only. Majority of the species (62.9%) recorded by the help of key informants are commonly consumed by human and animals. The total number of fruit/fodder species recorded (i.e., species richness) on agro-ecosystem and forest land of the study sites are indicated in the Table 1. | Table 1. Species Compositions at different Landuse and Species Richness pattern: Common Species Number at different Landuse |

| | Site | Cropland | Homegarden | Forest Land | | Cropland | 21 | 15 | 19 | | Homegarden | | 21 | 18 | | Forest Land | | | 32 |

|

|

The Shannon-Weiner diversity index was high in the natural forest followed by cropland, which is associated with the high evenness in the abundance of species in the natural forest as compared to the cropland and homegarden (Table 2). Simpson diversity index exhibited similar trend as that of Shannon-Weiner diversity index.| Table 2. Diversity Indices of Woody Species at Enda Mekhoni, Tigray, North Ethiopia |

| | Landuse | Shannon-WienerDiversity Index | SpeciesEvenness | | Cropland | 2.35 | 0.773 | | Homegarden | 2.093 | 0.687 | | Forest Land | 2.793 | 0.806 |

|

|

3.2. Similarity in Species Composition

The result of current study showed that 71.4% of the species recorded from homegarden also found in cropland, 90.5% of species found in cropland also found in forest land and 85.7% of the species recorded in homegarden also observed in forest land (Table 1).The Sorensen coefficients of similarity showed highest similarity in fruit and fodder tree/shrub species composition between crop field and forest land followed by between cropland and homegarden (Table 3).| Table 3. Sorensen Similarity Percentage in Woody Species Composition at Enda Mekhoni, Tigray, North Ethiopia |

| | Site | Cropland | Homegarden | Forest Land | | Cropland | 100 | 71 | 72 | | Homegarden | | 100 | 68 | | Forest Land | | | 100 |

|

|

3.3. Species Abundance

Opuntia ficus-indica is an abundant fruit and fodder species in crop land, home garden and forest land use (Table 4). It is also frequent species in crop field while Euphorbia tirucalli and Acacia etbaica are frequent in home garden and forest land use respectively (Table 5).| Table 4. Abundance of fruit/fodder tree/shrub species by rank |

| | Rank | Cropland | % | Homegarden | % | | 1 | Opuntia ficus-indica | 26.70 | Opuntia ficus-indica | 40.00 | | 2 | Euphorbia tirucalli | 22.62 | Euphorbia tirucalli | 22.11 | | 3 | Faidherbia albida (Acacia albida) | 10.41 | Faidherbia albida (Acacia albida) | 5.79 | | 4 | Acacia nilotica | 6.79 | Cordia africana | 4.74 | | 5 | Acacia abyssinica | 5.88 | Acacia abyssinica | 3.68 | | Rank | Forest Land | % | | | 1 | Opuntia ficus-indica | 22.75 | | 2 | Acacia etbaica | 13.03 | | 3 | Faidherbia albida (Acacia albida) | 8.53 | | 4 | Acacia nilotica | 6.87 | | 5 | Acacia abyssinica | 5.21 |

|

|

| Table 5. Species frequently observed at different land use in Enda Mekhoni, Tigray, North Ethiopia |

| | Rank | Cropland | % | Homegarden | % | | 1 | Opuntia ficus-indica | 14.95 | Euphorbia tirucalli | 18.82 | | 2 | Faidherbia albida (Acacia albida) | 14.02 | Opuntia ficus-indica | 16.47 | | 3 | Euphorbia tirucalli | 11.21 | Acacia etbaica | 9.41 | | 4 | Acacia nilotica | 9.345 | Faidherbia albida (Acacia albida) | 8.23 | | 5 | Acacia abyssinica | 8.41 | Acacia abyssinica | 5.88 | | Rank | Forest Land | % | | | 1 | Acacia etbaica | 10.09 | | 2 | Faidherbia albida (Acacia albida) | 9.17 | | 3 | Acacia nilotica | 8.72 | | 4 | Opuntia ficus-indica | 7.80 | | 5 | Acacia abyssinica | 7.34 |

|

|

3.4. Species Preference

Based on the species preference of the respondents, top fruit and fodder tree/shrub species are identified and indicated in Table 6.| Table 6. Fruit and fodder tree/shrub species preferred at Enda Mekhoni, Tigray, North Ethiopia |

| | Rank | Fruit Species Preferred | Fodder Species Preferred | | 1 | Opuntia ficus-indica | Faidherbia albida (Acacia albida) | | 2 | Ziziphus spina-christi | Acacia nilotica | | 3 | Mimusops kummel | Ziziphus spina-christi | | 4 | Prunus persica | Becium grandiflorum | | 5 | Balanites aegyptiaca | Acacia seyal | | 6 | Ximenia americana | Grewia bicolor | | 7 | Cordia africana | Balanites aegyptiaca |

|

|

3.5. Collectors and Users

According to the respondents about 79.2 % of fruits are exclusively collected by children from their sources and 20.8% of fruits are collected by adults. Among the fruit tree/shrub species identified only about 33.3% are consumed by all age group.

3.6. Domestication Process of Fruit/fodder trees/shrubs

The selection, retention or deliberately planting and management of trees by farmers can be considered as the beginning of the domestication process of the species. Out of the fruit/fodder trees/shrubs identified in the area only few of them are managed by the farmers for fruit/fodder. According to the respondents (91.67), Opuntia ficus-indica, Ziziphus spina-christi, Mimusops kummel and Prunus persica are the species intentionally retained/planted for their fruit. The same proportion of the respondents explained that Faidherbia albida, Acacia nilotica, Ziziphus spina-christi and Becium grandiflorum are maintained for their fodder.According to the explanation of farmers they do not retain/plant trees from forest origin due to several reasons viz. lack of water, shortage of land, low income, slow growth and lack of availability of seedlings (Fig. 3).  | Figure 3. Factors that affect tree retention/planting by farmers |

4. Discussion

Highest diversity of fruit and fodder tree/shrub species recorded in Enda Mekhoni woreda. This can be explained as local people have the knowledge of the uses of indigenous tree/shrubs. Although large number of fruit and fodder tree/shrub species is mentioned through the present study, only few species are highly preferred by all age group while majority of the fruits are exclusively collected and consumed by children. They have ranked these species for their multipurpose function. Opuntia ficus-indica, Ziziphus spina-christi, Mimusops kummel and Prunus persica are the species intentionally retained/planted for their fruit while Faidherbia albida, Acacia nilotica, Ziziphus spina-christi and Becium grandiflorum are maintained for their fodder. The reason for planting or maintaining highest diversity of fruit and fodder tree/shrub species might be mainly to support income and nutritional security. Farmers consider trees of forest origin as slow growing and low income yielding, so they are not willing to share the resources viz. land, water, etc. for these trees and show less interest to retain/plant these trees. Farmers consider different attributes as criteria when deciding to retain/plant a specific tree species. These attributes or purposes include income contribution, food, fodder, fuelwood production, construction materials (for fencing, housing and making household utensil and farm implements), watershed benefits (e.g., soil conservation), and shelter for animals. Farm households will also plant tree species on the basis of specific attributes such as fast growth, ability to protect against winds, and so on. For instance, several study showed that Faidherbia albida (Acacia albida) is retained or planted by farmers for its fodder and environmental purposes [13-14]. Fruit/fodder resources are widely distributed in forests lands than the off-forest habitats suggest that domestication of fruit and fodder is still lacking in the study area. Many potential trees/shrubs are present in nearby forest area but not yet domesticated. This reveals the scope for the domestication of these underutilized species in the study area. Even few trees on crop land and homegarden are not intentionally managed to improve or use the products for fruit and fodder sustainably which imply that proper domestication of fruit/fodder species is lacking. It is well known that farmers need understanding and skills to domesticate and integrate fruit and fodder trees/shrubs in to their farming systems [15]. Although not quantified exactly, trees/shrubs of the study area contribute to food security by their fruit and fodder. Children and women make money (hundreds of Birr a year) by selling fruits of some tree/shrub species from wild source and agricultural landscapes. The fodder species from trees/shrubs are consumed by animals during dry season suggests that trees/shrub species supplement animal feed otherwise animals are sold with cheap price or suffer from scarcity of grasses. Trees and shrubs fodder are the important component of animal feed in dryland areas compared with grasses [16] though many of them are not cultivated [17]. According to WAC [15] indigenous fruit trees have always been important to the rural people. A survey in Malawi, Mozambique and Zambia indicated that half of rural households relied on indigenous fruits to sustain them during critical period.

5. Conclusions

The result of the present study depicts that forest site has highest fruit and fodder tree/shrub species diversity as compared to other land uses. However, only few species are managed for their fruit and fodder purpose. Farmers consider different attributes as criteria when deciding to retain/plant a specific tree species. Opuntia ficus-indica, Ziziphus spina-christi, Mimusops kummel and Prunus persica are the species intentionally retained/planted for their fruit while Faidherbia albida, Acacia nilotica, Ziziphus spina-christi and Becium grandiflorum are maintained for their fodder. Many fruit/fodder tree and shrub resources are widely distributed in forests lands than non-forest habitats which suggests that there is a potential for domestication of fruit and fodder trees or shrub species in the study area. The fact that the lack of deliberate planting /retaining of fruit and fodder shrubs/trees by farmers in the area may have been caused by a lack of information on the economics of production and the long term benefits to the overall farming systems. Based on the present findings the following points are recommended: ● Fodder and fruit tree are recommended to be incorporated with farming in different approach, on pocket of land such as farm boundary and hedgerow in crop land to for nutritional security and for improved animal production. ● Researches on nutritional value, propagation, and interaction of fruit and fodder species with annual crops and qualitative economic analysis of the species are highly recommended for the study area.● Intervention on management and seedling production in nursery is essential to accelerate the domestication process in the study area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by research and publication office (RPO) of Mekelle University, Ethiopia. We would like to thank College of Dryland Agriculture and Natural Resource for facilitating financial matters and other support. We also would like to thank Mr. Redae Taddess, Mr. Yigzaw Tadelle, and Mr. Muez Kasay for their field assistance.

References

| [1] | Sene, E.H., Forests and food security in Africa: the place of forestry in FAO's Special Programme for Food Security, Rome, Italy, 2000. |

| [2] | FAO, Non-Wood Forest Products. Proceedings, Arusha, Tanzania, 17-22 October 1993, Agriculture Programme, 1993. |

| [3] | Jama, B.A., Mohamed, A.M., Mulaty, J. and Njui, A.N., “Big Five”: A framework for the sustainable management of indigenous fruit trees in the drylands of East and Central Africa, Ecological indicator 8(2): 170-171, 2008. |

| [4] | Styger, E., Rakotoarimanana, M.E.J., Rabevohitra, R. and Fernandes, E.C.M., Indigenous management of tropical forest ecosystem: the case of the kayapo Indians of the Brazilian Amazone, Agroforestry system 3(2):139-158, 1985. |

| [5] | Libby, W.J., Domestication strategies for forest trees, Canadian Journal of Forest Research 3: 265-276, 1973. |

| [6] | Leakey, R.R.B. and Newton, A.C. (eds), Tropical Trees: The potential for Domestication and the Rebuilding of Forest Resources, The proceedings of a Conference organized by the Edinburgh Center of Tropical Forests held at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh on 23-28 August-1992, 1994. |

| [7] | ICRAF, Annual Report 1995, ICRAF, Nairobi, 1995. |

| [8] | Nikiema, A., Agroforestry parkland species diversity: Uses and Management in Semi-Arid West Africa (Burkina Faso), PhD thesis Wageningen University, Wageningen ISBN 90-8504-168-6. 102 pp, 2005. |

| [9] | Krebs, C.J., Ecological Methodology (2nd ed), Addison Wesley Longman, inc. Menlo Park, California. 454 pp, 1999. |

| [10] | Shannon, C.E. and Wiener, W., The mathematical theory of communication, The University of Illinois Press, 1949. |

| [11] | Magurran, A.E., Ecological Diversity and Its Measurements, Chapman & Hall, London.179 pp, 1988. |

| [12] | Kent, M. and Coker, P., Vegetation Description and Analysis: A practical approach, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester. 363 pp, 1992. |

| [13] | Wood, P.J., Faidherbia albida - A monograph, Center Technique Forestier Tropical Division of Cirad. Oxford forestry institute, England, 1989. |

| [14] | World Agroforestry Center (WAC), Creating an evergreen Agriculture in Africa for food security and environmental resilience, World Agroforesty Center. Nairobi, Kenya. 24 pp, 2009. |

| [15] | World Agroforestry Center (WAC), Annual report 2007-2008, Agroforestry for food security and healthy ecosystem. Nairobi, Kenya: World Agroforesty Center, 2008. |

| [16] | Chen, C.P., Halim, R.A. and Chin, F.Y., Fodder trees and fodder shrub in range and farming systems of Asian and Pacific region, In: Legume trees and other fodder trees as protein sources for livestock. Proceedings of the FAO Expert Consultation, Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14–18 October-1991, 1992. |

| [17] | Raghavan, G.V., Availablity and use of shrubs and tree fodder in India, In: Devendra, C.(ed.), Shrubs and tree fodders for farm animals. Proceedings of a workshop in Denpasar, Indonesia, 24-29 July 1989. IDRC-276e, Ottawa, Ontario, pp. 196-210, 1990. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML