-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Ecosystem

p-ISSN: 2165-8889 e-ISSN: 2165-8919

2014; 4(2): 53-59

doi:10.5923/j.ije.20140402.02

Climate Change Adaptation in Semi-Arid Areas: A Gender Perspective

Venance Kalumanga1, Mark M. Msaki2, Fadhili Bwagalilo3

1Institute of Development Studies, St John’s University of Tanzania (SJUT), P.O. Box 47, Dodoma Tanzania

2Department of Rural Development and Regional Planning, The Institute of Rural Development Planning (IRDP), P.O. Box 138, Dodoma, Tanzania

3Department of Geography, St John’s University of Tanzania (SJUT), P.O. Box 47, Dodoma, Tanzania

Correspondence to: Venance Kalumanga, Institute of Development Studies, St John’s University of Tanzania (SJUT), P.O. Box 47, Dodoma Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

At current, the world is struggling to mitigate the impacts of Climate Change to the involved communities. Due to their climatic behaviours, Semi-Arids are among the most vulnerable areas to Climate Change. Adaption to Climate Change has been suggested to lessen the impacts in different areas. However, the adaption is relative to a specific area’s social-economic, physical as well as cultural set up. For this fact, it is a matter that in some areas, culture happens to side-line women in decision making and implementation while adapting for Climate Change. Therefore, the study was carried out at Chololo Eco - Village, in Dodoma Municipality. The aim of the study was to assess the existing climate change adaptation strategies or technologies and the involvement of Gender in Addressing Climate Change Adaptation Technologies. A total of 110 respondents were interviewed. The research revealed that among the proportion 36%, 29%, 35%, 32%, and 59% of female respondents attended transfer of innovation sessions for Agriculture, Water Management and Conservation, Afforestation, Food Security and Economic Adaptation. More men attended sessions for transfer of innovations as compared to women. Tradition, culture and household chores impended women not to involve much in such sessions. Fortunately, women not attending in such session did not connote not adapting to Climate Change. Roles occupied in the community and household chores had been the factor for women to decide whether to participate or not participate in the training sessions. Women struggled to attend transfer sessions which seemed to be critical such as Economic Adaptation. Fruitfully women were found to be more involved in Income Generating Activities (IGAs) introduced by Chololo Eco – Village. Deliberate efforts should be carried to ensure that women attend technology transfer sessions to become the first beneficiaries of such innovations.

Keywords: Climate Change, Adaptation, Innovation, Gender Involvement

Cite this paper: Venance Kalumanga, Mark M. Msaki, Fadhili Bwagalilo, Climate Change Adaptation in Semi-Arid Areas: A Gender Perspective, International Journal of Ecosystem, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 53-59. doi: 10.5923/j.ije.20140402.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Climate change is now a global issue posing challenge to the survival of humankind and sustainable development. The adverse impacts of climate change are now evident almost everywhere. In Tanzania climate change is manifested in various ways, the extreme drop of water levels of Lake Victoria, Lake Tanganyika and Lake Jipe in recent years and the dramatic recession of 7km of Lake Rukwa in about 50 years, are associated, at least in part, with climate change, and are threatening economic and social activities. Eighty per cent of the glacier on Mount Kilimanjaro has been lost since 1912 and it is projected that the entire glacier will be gone by 2025. According to the National Adaptation Programme of Action, semi-arid areas are the most vulnerable to climate change impacts. Predictions show that the mean daily temperature will rise by 3℃ – 5℃ throughout the country and the mean annual temperature by 2℃ – 4℃. There will also be an increase in rainfall in some parts while other parts will experience decreased rainfall. Predictions further show that areas with bimodal rainfall pattern will experience increased rainfall of 5% – 45% and those with uni-modal rainfall pattern will experience decreased rainfall of 5%– 15%.Gender refers to different social roles that women and men play, and the power relations between them [1]. These social roles also determine the magnitude of impact of Climate Change to a particular group. The changes of the climate and its impacts are already occurring and touching the lives of poor people all around the world, especially in developing countries [2]. Climate change affects men and women differently because men and women play different roles and have different responsibilities in the societies. These differences define inequalities between men and women hence setting vulnerability magnitude to climate change [3]. Limited access to resources and decision making, as well as limitation to mobility places women in developing countries in a position to be mostly affected by Climate Changes. Rural women are engaged in most Climate Changes related activities than what is reported, documented or recognized by the public [13]. Concurrently, the effects of Climate Changes are significantly impacting on poor people, particularly women. Women have been carrying the major responsibility for household such as water supply, energy for cooking and heating and are responsible for household food security [4, 14]. While 80% of the household food is grown by female in sub-Saharan Africa [4], women and children comprise an estimated 70% of the world’s poor [22]. Experience in Thailand showed that women, who are the mostly affected to Climate Change, are also the one’s pronounced to heavy activities contributing to Climate Change occurrences [5]. In both Namibia and South Africa it is believed that men and women are faced with different vulnerabilities to climate change impacts due to the existing inequalities, such as their roles and positions in the society [6, 31). Climate change is exacerbating the problems and inequities that women are already facing. Women’s livelihoods are highly dependent on natural resources which are heavily threatened by climate change. Widely, experience shows that women are the ones severely affected by climate change [7, 8].Similarly, women in Tanzania are not only victims of climate change but are also effective agents of change in relation to adaptation, and disaster reduction strategies [15]. Their responsibilities in households and communities as guardians of natural resources have prepared them well for livelihood strategies adapted to changing environmental realities. Given their roles in society, (production and reproduction) women have important knowledge, skills and experiences for shaping the adaptation process and the search for better and safer communities [15].Tanzania’s economy is prone to Climate Change as it is having its large proportion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) associated with climate sensitive activities such as smallholder agriculture [16]. Rainfall seasons have become shorter and more irregular thus affecting the potential growth period for both food and cash crops grown in semi-arid areas [17]. Such climatic shifts also affect regeneration of rangelands leading to insufficient pastures in semi-arid areas [18]. Extreme events such as droughts and floods are reported to be blowing Tanzanian economy. Individual annual events have economic costs in excess of 1% of GDP, and occur regularly, reducing long-term economic growth, while affecting millions of people and livelihoods, women being most severe [19]. Future Climate Change could lead to large economic costs while uncertain, aggregate models indicate that net economic costs could be equivalent to a further 1 to 2% of the GDP year by 2030 [20]. Tanzania is not adequately adapting to the current climate change. The country therefore has a large existing adaptation deficit which requires urgent action, and to be specific in semi-arid areas [21]. As mentioned earlier, women have vital role in agriculture production but the poorest. Gender roles are surely affected by the Changing Climate and not in favour of women. Understanding gender differentiated impacts are important to formulate an effective and sustainable adaptive response to climate change. Adaptation to climate change is important to make human societies well suited to climates they live in [10]. Developing activities to adapt climate change must systematically and effectively address gender-specific impacts of climate change [10; 11; 12]. Dodoma region is semi – arid, with erratic rainfalls averaging at 570 mm annually [23, 24]. Rainfall pattern is uni-modal where 85% of the rains do fall in the months between December and April [23]. Such rainfall pattern in Dodoma makes it impossible to maintain agricultural societies through unstable and capricious rainfall [23; 24]. Dodoma is pronounced to have frequent famines caused by semi-arid natural conditions[24]. Current research conducted in Makoja village shows about half of villagers are chronically food insecure [28]. Chololo village is among of the poorest and food insecure semi-arid villages in Dodoma municipality. The situation prevailed at Chololo Village called six agencies from Dodoma Regional to work together to transform Chololo village into an Eco – Village. The consortium working under the leading of the Institute of Rural Development Planning is supporting and empowering the community to test, evaluate and take up new innovations in agriculture, livestock, water, energy, and forestry. The European Union have been providing 90% of funds to support the project. However, while various agencies do address Climate Change adaptation in Tanzania, they have not been providing adequate attention to the role of women in adapting climate changes. Either, no enough information is yet provided to show the response of women towards such initiatives. As mentioned earlier, women occupy the significance importance in reaching success to adapt the impacts of Climate Change in the country [25]. Therefor this paper aims at, 1.1. Briefly highlight climate change adaptation strategies in semi-arid Dodoma. 1.2. Examining the involvement of women in addressing climate change adaptation technologies in semi-arid area with particular focus on Chololo Eco-village.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. The Study Area

- The study was conducted at Chololo Village in Dodoma Municipality. The village is located about 46 km outside of Dodoma town 15 km from the Dar es Salaam road. It is found at latitudes -6.2428 and longitudes 36.0003.The village is have six hamlets namely: - Kawawa, Lusinde, Jamhuri, Muungano, Siasa, and Kizota. During 2012 census, the total population and total number of the households at the village was 7,500 people and 1,111 respectively [32]. This village was selected for the study since there has been an on-going effort to transform Chololo village into an Eco-village.

2.2. Data Collection Methods

- Both primary and a secondary data were collected and used to explain on the involvement of women in adapting to Climate Change. Primary data were collected by using direct observation method, face to face interview and telephone interviews. Direct observation method involved visiting the village and observed the natural settings of the village projects like, farms, water harvesting project, skin turning project, bee farm project, fish production project and other projects. Face to face interview involved structured questions which were related to the study. Both closed and open ended questions were administered to the head of the household both women and men.Secondary data were collected through the reviews of documentaries, relevant journals, text books, articles, published papers, and electronic libraries. Documentary review method involves deriving information by careful studying written documents [26). Documentary review was geared towards obtaining data related to statutory and policy issues like the consideration of women’s to the issues of addressing climate change adaptations [27]. Furthermore, content analysis was used to analyse data from focus Group Discussion while Special Package for Social Science was used to analyse all quantitative data.

3. Results and Discussion

- Involvement of women in development projects has been a challenge in many parts of Africa and Tanzania in particular. While there is a wide range of issues where women are seriously supposed to be part of decision making as well as implementation, this paper only highlights on women involvement in climate change adaptation strategies. These strategies are termed as technologies and are as follows; - Agriculture adaptation technology, Water adaptation technology, Energy adaptation technology, Food security adaptation technology, and Economic adaptation technology. As all of the five innovations have been well addressed in Chololo Eco- village, the understanding the involvement of women will provide a benchmark of success for such initiatives.

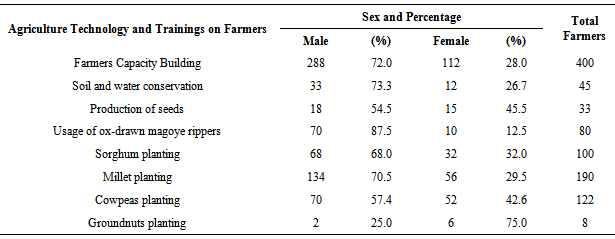

3.1. Gender Involvement on Agriculture Technology Innovation

- Women appeared to have relatively low participation in all innovations but not to groundnut planting (see Table 1). Traditionally, there has been low emphasis in growing groundnuts in Chololo village. Relatively higher proportion of women in growing groundnuts can explain that groundnut is a crop important to females. Although females were relatively low engaged in various other activities they turned up in production of seeds and planting cowpeas. The current findings relate various studies showing that although most crops are grown by both men and women, there are still patterns of cropping by gender [29, 30]. Some crops have a greater proportion of women growing them and some are more likely to be grown by women than by men. The majority of the respondents (55%) admitted that the task for fertilizers application was done by the women. The proportion 31% reported that men contributed in fertilizer application. Fewer respondents (14%) reported that both male and female participate in farm fertilizer applications.On average, while the participation of males in Agriculture Technology Transfer was 64%, the participation of women was relatively low (36%). More men were engaged in the implementation of the new technology transfers of agriculture.The above data also agreed from the most researchers who wrote some information on the participation of women and men on farm tasks. Lots of women can do and are already participating to adapt to climate change. The findings relate to the 1998-99 study in Malawi attempting to determine socioeconomic characteristics of the farmers collaborating with the extension service, and to assess farmer opinions regarding the cropping systems being promoted. The study revealed that male farmers had significantly greater experience as head of household, used more fertilizer, and devoted a greater area to cash crops [30].

|

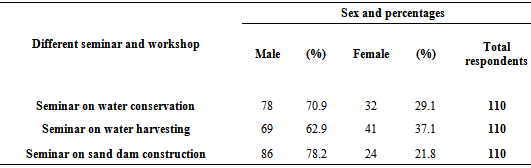

3.2. Gender Involvement in Water Adaptation Technology

- The participation of the women and men in different seminars and workshop of addressing water was assessed. Water conservation, water harvesting and dam construction was introduced as the means to solve the problem of water in the village. Results showed that on average, the majority of the respondents (71%) who participated in both seminars were men and only 29% were women (Table 2). Men showed positive participations to all seminars compared to women. Relatively

|

3.3. Gender Involvement in Energy Adaptation Technology

- Household energy was earlier noted as the problem in Chololo village. The majority of surveyed households (92.7%) admitted that they were using firewood as the source of cooking energy in the year of 2010. However, the start of the Eco-village project reduced the proportion using firewood for cooking from 92.7% in 2010 to 71% in the year 2012. Although the number of the people who still use firewood as the source of energy is large, planting of trees become important in stabilizing the environment. Data showed that the majority of participants in the afforestation training at Chololo village were male (65%).Although not many women did attend the afforestation training program, they have been in frontline in planting of trees in the community. Firewood collection has been the responsibility of women; women have been at the forefront of initiating tree nurseries and planting activities around their homes and in farms in order to restore the loss of trees being cut for firewood and charcoal. Culture and other household chores were reported to make their participation low. The current findings resemble the study in Malawi which revealed that although women did not show up in extension programs, the yields at their households portrayed that they equally used fertilisers [30]. The findings suggested that women who did not attend the trainings sought to know what was trained through the women who attended the sessions or their male counterparts.

3.4. Gender Involvement in Food Security Adaptation Technology

- Data revealed that the majority 68% of the farmers who were involved in the food security adaptation technology were men and only 32% were female. The data was contradicting to the emphasis and arguments of many researches who argued on the involvement of female to be high percentage than male. It has been argued that women in most communities have the responsibility to care for the household food security including the production, collection and storage of food [28). Women know the food required for the family in a week, a month as well as a year. In Chololo village women use local knowledge to prepare, process and store vegetables and fruits during the growing season in order to use them in the dry season when vegetables and fruits are not available (see Plate 1).

| Plate 1. Women in Chololo village preparing vegetable for future use |

3.5. Gender Involvement in Economic Adaptation Technology

- Women have been engaging more pro-actively in initiating and running small economic activities such as keeping and sale of small-stock poultry, piggery, goat, pigeon peas, dairy cows [33]. Growing and selling of surplus vegetables, particularly during the dry season, mushroom production and fishing. Traditions and culture have been impeding women from engaging in economic activities. After the start of the project women become active to participate in many of the economic activities so to raise their economic status. In 2012, the majority of participants (59%) who participated in economic activities implemented by the Cholol Eco-Village were females. Women at Chololo village have been in front line to support the economic projects which address the issues of climate change adaptation. Among of the economic projects introduced were chicken keeping, fish keeping, bee keeping, and milk cow keeping and tanning of cattle skin. Most of the women in Chololo village have been proud with the tanning of skin project as it is among of the brilliant and high paying project where women do generate enough money to curb their basic required needs (see Plate 2).

| Plate 2. Goat skin processed into productive leather |

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

4.1. Conclusions

- As compared to females, males were found to be more participating in sessions for transferring technologies for Climate Change. Tradition, culture set ups and household chores have been the reasons for the poor involvement of the women in such sessions. Roles occupied in the community and household chores had been the factor for deciding to participate or not participate in the training sessions. Women had been the majority who attended training in processing skin. Women, were also been found actively involved in Income Generation Activities (IGA’s) introduced by the Chololo Eco Village project. Not largely attending the sessions did not connote that technology had not been transferred and utilised by women in Chololo Eco Village. Either it did not connote that males have been replaced women in their Climatic roles. Innovations introduced and facilitated by Chololo Eco-Village has been important to assist such poor and vulnerable communities adapt to climate change and improve their livelihoods.

4.2. Recommendations

- Scaling up of initiatives such as the one carried at Chololo Eco-Village is commended to assist various communities to adapt to climate change and improve their livelihood. Although tradition, culture and household chores have impended women not to fully participate, there is a need to reorganise the programs to involve more women at first hand as they most impacted by climate change compared to men. Direct involvement of women in transfer of climate change adaptation activities or technologies is of paramount importance to realise fast progress. More studies aimed at promotion of women participation in such activities are suggested.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- At first and foremost, the authors acknowledge the Chololo community to agree to participate in the study. The Authors are also grateful to the Research and Post - Graduate committee of the St John University of Tanzania (SJUT) to approve for the study to take place. The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the Chololo Eco-Village Project Team for according cooperation when required. As the outputs were based on data obtained from survey, the authors team declares that the findings obtained in this study not necessarily that of the Chololo Eco - Village Project.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML