-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Ecosystem

p-ISSN: 2165-8889 e-ISSN: 2165-8919

2013; 3(6): 177-184

doi:10.5923/j.ije.20130306.03

Integrating Geospatial Decision Support Systems with Indigenous Knowledge in Natural Resource Management

Bwagalilo Fadhili1, Evarist Liwa2, Riziki Shemdoe3

1Department of Geography, St John’s University of Tanzania, P.O.Box 47, Dodoma, Tanzania

2School of Geospatial Science and Technology, Ardhi University, P.O.Box 35124, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

3Institute of Human Settlement Studies, Ardhi University, P.O.Box 35124, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Correspondence to: Bwagalilo Fadhili, Department of Geography, St John’s University of Tanzania, P.O.Box 47, Dodoma, Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Management of natural resources in Tanzania reflects prevailing policies of the various institutions involved. These policies are the result of decisions made to manage either countrywide or specific area resources. The fact is that, geospatial decisions are associated with considerable information coupled with the improvement of human understanding of the natural resource base increases the complexity of the natural resource management decision making process. This has required the development of new skills to aid managers in their decision making. One of these skills is referred to as Geospatial Decision Support System (GDSS). Despite the development and use of GDSS in natural resource management the degradation rate of natural resources is on the increase. Along with that there is a worry that GDSS leads into top down decision making because it overlooks the significance of indigenous knowledge. Indigenous knowledge is essential as part of information gathering and natural resource management decision making. Overlooking these factors have led to an increased degradation of natural resources despite the use of GDSS. The problem is the lack of integration of the two systems. Therefore this paper will discuss and highlight theoretical advantage of integrating GDSS and indigenous knowledge for improved and informed decisions on natural resources management. Specifically it identifies the importance of indigenous knowledge together with GDSS in natural resource management. It also highlights the potential danger of overlooking the importance of indigenous knowledge in natural resource management. Finally this paper recommends the integration of the two for rational objective decisions on natural resource management with particular focus on forest management

Keywords: Decision Support Systems, Indigenous Knowledge, Natural Resource Management

Cite this paper: Bwagalilo Fadhili, Evarist Liwa, Riziki Shemdoe, Integrating Geospatial Decision Support Systems with Indigenous Knowledge in Natural Resource Management, International Journal of Ecosystem, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 177-184. doi: 10.5923/j.ije.20130306.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Natural resources provide the basis of living and survival of humans on earth[1]. Because of this there is a concern to manage the resources that is growing every day and has resulted in the establishment of national and international institutions to manage natural resources. They operate within the framework of plans, policies and programs, their decisions depend on information made available to them relative to that development era. Currently science and technology era applies to almost every aspect of decision making and therefore seems to replace traditions which were in place and previously used by the decision making bodies. For instance the adoption of geospatial information technology has enabled decision makers to work and make decisions on natural resources with minimal attention to indigenous knowledge (IK). The technology abides what is known as Geospatial Decision Support Systems (Remote Sensing and Geographical Information Systems). The GDSS has Minimized reliance on indigenous knowledge in decision making therefore signifying the possibility of a top down management approach, which[2] criticises it as an approach which does not favour community wellbeing.IK has for decades been used in decision making at the local level mainly focusing on the welfare of concerned social organisations with minimal consideration to the technical aspect as provided by geospatial information. Besides, both GDSS and IK ought to manage natural resources. Regardless of the possible outputs of either of these tools in decision making concerning natural resource management, comparing the effectiveness of the two and finding a way to integrate the two systems is significant for the wellbeing of the community and the ecosystem. GDSS has made NR information management easier in all aspects collecting, storing, processing, manipulating and communicating information to support decision making. It helps natural resource managers and workers analyse problems, visualize complex subjects and create new products. In spite of these, still, it does not have significant reasons to overlook IK in decision making.Unlike GDSS, roles of IK have received a minimum attention as an aspect which can also assist decision making. These set of perceptions, information and behaviours known as IK are very important because they guide the local community member’s uses of the land and natural resources. These perceptions are unique, traditional, local knowledge existing within and developed around the specific condition of a particular area in a particular locality. It is therefore important information to aid decision making, the knowledge has shaped thinking in management of NR for decades in the Southern African Countries. For this reason IK needs to be validated, reinforced, disseminated, innovated and preserved through practice. In the current era, it is significant by integrating it with GDSS. The argument in place is that GDSS is generally a top down approach to decision making, from expert to target group rarely incorporating indigenous IK.This paper therefore, calls for an in-depth consideration of IK in different aspects of management decision making particularly in this era of advanced proliferation of science and technology of information related to natural resource management decision making by making a model that will include IK in GDSS. A decade ago, it was acknowledged by[3] that geospatial information can be used with other databases and models at the various decision making stages. It’s therefore, high time that this is implemented in developing countries NRM. This will ensure Quality decisions concerning natural resources which will form a very significant link between natural resources and socio economic wellbeing of human population. With that concern this paper aims at;1. Highlighting countries’ forest governance, economy an forest dependency 2. Describing GDSS and indigenous knowledge in Forest Management3. Assessing and suggesting possible integration of the various approaches to FM

2. Methods

- Socio Ecological Systems Model and Turban’s framework for planning and decision making were used as basis of argument in decision making. Literature survey was used as a main data collection method. The two methods were also used for analysing the content collected from various sources of literatures.

3. Results

3.1. Natural Resource Policy, Legal and Institutional Framework

- In any nation the economic development is very closely linked to the proper management of the country’s Natural resources. At the national level, government policy and legal frameworks provide the basis of governing these natural resources. In Tanzania there are different institutions managing natural resources. However, three institutions can be explicitly singled out responsible for natural resource management, Particularly in forest resources;1. The Ministry of Natural Resource and Tourism;2. The Division of Environment under the supervision of the Vice President; and3. The National Environmental Management Council.These institutions are led by policies, strategies and legal frameworks. Policies and legal frameworks are specific to a particular type of resource but must also take into account the intermingling characteristics of the natural resources, [4]. The relevant policies and legal acts affecting the forest are:1. The Forest Policy (1998);2. The Forest Act (2002); 3. The National Irrigation Policy (2009);4. The National Water Policy (2002; 5. The National Water Sector Development Strategy (2006);6. The Water Resources Management Act n 11 (2009); 7. The National Environmental Management Act (2004);8. The Village Land Act (1999);9. The National Population Policy (1996);10. The National Agricultural and Livestock Policy; and 11. The National Strategy for Growth and Poverty Reduction[4].By definition under the Tanzania Forest Act (2002) and its Regulations (2004); Tanzania possesses several different forms of forest management. About 13 million hectares have been gazetted as forest reserves. Of this over 80,000 hectares is under plantation forest and approximately 1.6 million hectares is under water catchment management. Both the policies and legal frameworks of this Act and its Regulations insist on participation of local communities in managing resources. However in practice this management leaves much to be desired. The community’s participation is either taken for granted or used as a rubber stamp to win funds and justify decisions already made on natural resource management.

3.1.1. Tanzania Economy and Natural Resources (Forest) Governance Relationship

- Tanzania is among the developing countries. About 80% of Tanzanian households depend on agriculture as their primary economic activity. Most individuals in rural areas depend directly on natural resources for their livelihood. Agriculture contributes largely to the country's economy as also does tourism that has recently posted a solid growth rate in economic development. About 89 percent of the population lives below the $1.25/day (USD) poverty line[5]. Poverty in Tanzania is mainly a rural phenomenon, 83% of the low income people live in rural areas and depend on agriculture and natural resources as their main source of income[6]. This demonstrates the country’s dependence on natural resources. Tanzania has a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of USD 22.43 billion and a recent growth rate of 5-7% relative to current World Bank records. It is a natural resource rich country with a high diversity of land resources, water resources (both surface and ground water), forests, minerals and wildlife. These resources form an important base for the national economy and local livelihoods. Natural resources are estimated to contribute to about 34% to the GDP for the period 2001 to 2009[7]. According to the Ministry of Natural Resource and Tourism[8], the forest sector provides about 3 million person/years of employment. In Tanzania the forests provide both wood products and ecosystems services, offering varying benefits at international, national and local level. These include wildlife habitat, unique natural ecosystems and biological diversity, water catchments and climate regulation[9]. Concerns about economic development relate directly to the development of natural resources and particularly the management of these resources. Therefore decisions made about resource use needs to be reliable and sustainable. However, GDP calculations do not include aspects of indirect value of ecosystem service such as aesthetic value, optional values, preservation value, carbon sink et cetera. Therefore GDP by itself does not reflect the total economic value of the forest resources. Using technical based GDSS only includes direct use value alone in expense of indirect use value. Integration of indigenous knowledge is hypothesized to result in to green GDP.

3.2. Geospatial Decision Support Systems Tools

- In different literatures GDSS is treated as a separate entity, actually is an extension of GIS and RS. It is defined as an Interactive computer systems designed to support a user or a group of users in achieving a higher effectiveness of decision making while solving a semi-structured spatial decision problem”[10, in 11]. They are extension of GIS and remote sensing characterized with the following features 1. having an explicit geographic component2. supporting rather than replacing the user’s decision making skills3. facilitate the use of data, models and structured decision processes in decision makingGDSS does beyond what RS & GIS, however the two are significant pillars to GDSS, they provide input and aid in analysis to decision making supported by GDSS, below is a brief description of RS and GIS relative to NRM

3.2.1. Remote Sensing and Natural Resource Management

- Remotely sensed data analysed in a vacuum without the benefit of other collaborating information (such as soils, hydrology, topography, weather, etc.) is meaningless. This collaboration is what makes the use of remote sensing to a particular field advantageous, it can be used in numerous ways including aiding the analysis of the earth resources. RS plays a vital role not only in monitoring and mapping natural resources but it also provides near real-time information[12] see also, (Simonnet et al, 1983, Ehlers, 1996, Walter et al, 1996, and Taylor and Francis, 2005)Since the start of remote sensing technology there has been a proliferation of different satellites with different temporal and spectral resolution as well as different functions. Satellites that acquire images of the earth belong to two broad classes, earth resources satellites and environmental resources satellites. LANDSAT, for example, is the prototype for earth resources satellites designed to map renewable and non-renewable resources. Earth resources satellites are significantly used in managing NR in various ways, mainly by providing data and information to decision makers.

3.2.2. Geographical Information Systems and Natural Resources Management

- GIS technology has been used in public policy-making for environmental and forest planning and decision making over the past three decades,[13]. Geographical information systems and related technologies provide resource managers with powerful tools for record keeping, analysis and decision making. These systems can be established to provide crucial information about resources that can make planning and management of resources easier, e.g., recording and updating resource inventories, harvest estimation and planning, ecosystem management, and landscape and habitat planning. Nowadays, with improved access to computers and modern technologies, geographical information systems are becoming increasingly popular for resource management. Taking examples from forest management, forestry professionals have to understand the interconnectedness of, and the need to balance, the environmental and economic benefits that forest ecosystems provide[14]. Organizing, analysing, and presenting relevant information to policymakers, planners and managers are also some of the responsibilities of modern foresters[15]. It is these managers who need to address the interests and priorities of local communities and involve them in decision making[16]. Therefore forest resource management in today’s ever-changing world is becoming more complex and demanding to forest managers[17]. The challenge manifests the need for the application of geospatial information and technology to assist forest managers in making decision over the resources.

3.2.3. Indigenous Knowledge

- Herbal Medicine, which has benefited the lives of people around the globe, is a good example of IK. Literature on IK does not provide a single definition on it. Never the less several traits distinguish IK from other knowledge. Indigenous knowledge is unique to a particular culture and society. It is the basis for local decision-making in many different fields including agriculture, health, natural resource management and other activities. Indigenous knowledge is embedded in community practices, institutions, relationships and rituals.[18] Illustrated indigenous knowledge as the root, something natural or innate (to), it is an integral part of the culture. Indigenous knowledge contains an aspect of the community way of living which has long been the basis of justice, leadership, and among other items, management of the natural resources. In many developing countries, and Tanzania in particular, indigenous knowledge has been rapidly eroded by globalization, science and technology. It has for long been brushed aside and in many aspects has not been considered as part and parcel of decision making. However it has attracted the attention of many people in both developed and developing countries. As policies and legislative frameworks are developed the importance of both identifying and protecting indigenous knowledge is receiving increased attention from policy makers the world over. Incorporating indigenous knowledge into conservation and development activities is believed to be an important mechanism for ensuring the most efficient and productive use of natural resources in the short term without jeopardizing the long-term capacity of nature to continue producing these resources. One of the threats to sustainability of natural resources is the erosion of people’s indigenous knowledge. The basic reason for the erosion of this knowledge is the low value attached to it. Indigenous people have a considerable knowledge of their natural resources[18]. Integrating indigenous knowledge with geospatial information is a way to improving natural resources management as it will support decisions embedding local knowledge and scientific knowledge.

3.2.4. Indigenous Knowledge and Decision Making

- The respect of indigenous knowledge is one of the key aspects of good management and decision making. Indigenous knowledge is a positive measure of local community capability with potential to set community members on an equal status with outside experts. Indigenous knowledge may be the only resource of which the local group, especially those who are resources marginalised, have unhindered ownership. Ignoring indigenous knowledge in decision making leads to top down decision making based on technological expertise only. Often technology fails to supply sufficient information of the activity in question when it comes to implementation of the decision. Indigenous knowledge has the capacity to meet the pleased needs, answer the questions raised by the technological expertise derived from geospatial information, and address and satisfy the local stakeholders underlying interests. Therefore, for any developed decision support system, e.g. geographical information systems, the sustainability of the decision reached will greatly depend on the involvement of all stakeholders democratically and pro actively assuming decision making responsibilities. This must be done by their taking charge of their fate and that of the future generations, and in spite of a decision environment prone to faulty assumptions and lacking incentives for personal integrity. Sometimes indigenous knowledge is considered unimportant leading to conflicts and misunderstandings. In accordance with the Tanzania National Forestry Policy (1998), the Forest Act (2002) provides the legal framework to implement the National Forest Policy. Together with other objectives stipulated in the Act, the Forest Act (2002) aims to “encourage and facilitate the active participation of the citizen in the sustainable planning, management, use and conservation of forest resources through the development of individual and community rights, whether derived from customary law or under this Act, to use and manage forest resources.”

3.3. Natural Resource Management and Decision Making1

- The management of natural resources involves making decisions of about the, who, when, why and how of the resource use. These decisions need to integrate the needs of both of user and nature because without that the danger of resource degradation is high. This danger is demonstrated by the world ecological footprint2 versus its ecological capacity. According to Global Footprint Network, the world footprint is now 1.5 times the earth’s capability to generate the resource we use and absorb the waste. Tanzania particularly has a footprint of between 1.5 and 2 against its bio capacity of 3. The country’s footprint is still positive. However, the pressures of the ongoing global trade and global interaction put this status on threat. Only making of rational decisions on the resource management may save this nation from the major resource degradation being suffered by others.This degradation is already occurring however, Taking as an example; the forest resource depletion rate from 1990-2005, about 37.4% of Tanzania forest and woodland habitat have been degraded. This reflects on past decisions made on natural resource management. These decisions are influenced by the Policies, Acts, and Strategies of the various institutions in managing this resource. These decisions control resource management and so they need to be significantly put in a way that the results in a balance of the bio capacity of the nations and their footprint. Technical expertise based solely on information from GDSS results into expansion into protected areas, displacement of villages and restriction of forest accessibility. Decisions of this kind remove a sense of ownership of the resource from the community. This lack of ownership removes any inhibitions of the local community in removing forest resources. Had the community’s way of living and interaction with the resources been considered the likelihood of minimizing this degradation is significant? Technical support (GDSS) integrated with non-technical support i.e. indigenous knowledge, is likely to result in best objective decisions of natural resource management.

4. Discussion

- Literature has provided an insight into natural resource management, GDSS and IK. All these areas of expertise need to be interconnected to support decision making. The question now arising is; what should be the right way to integrate them? A theory developed by Ludwing Von bertalaffy (1901-1972) highlights aspects of a system theory as an appropriate way to integrate different complex entities to support decision making. According to Von bertallaffny , decision making as a process should not be done by treating individual elements of decision making separately, elements should be treated in a holistic and integrated way. Elements leading to a certain decision should not be treated in isolation rather they should be treated as a collection of elements. GDSS and IK together can be integrated to support decisions of natural resources management that will balance the needs of the ecosystems and also the needs of the community. See also in Tripathy and Bhattarya, (2004), Barton et al, (2005), and Mbilinyi et al (N.d). Different theories guides on how things should be done, we have many theories in decision making too, for this paper the reference is on bertallaffny theory and decision making, game theory, and socio ecological model by olstrom.The aforementioned guides the way on making important decisions that affect the human society and community, for example, important social demographic and infrastructural matters or any other issues. The subject is not very unified. Most of the time decision making is preceded by a process of participation procedure which GDSS may overlook.Decision-making is an accepted part of everyday human life. Individuals make decisions on the spur of the moment or after much thought and deliberation, or at some point between these two extremes. The managerial roles within organizations and/or institutions are expected to make decisions as an important part of their responsibilities. Decisions may be influenced by emotions or reasoning or by combination of both[19].Consider the Game Theory and the Socio Ecological Theory described below. The two theories insist on perfect and multi criteria integration to support decisions. In game theory a decision depends on information gathered by decision maker against the opponent. Similarly with Socio Ecological Theory, that calls for considerations of the community’s social needs and ecological balance before deciding on the natural resource use. This again is significantly possible when GDSS is integrated with indigenous knowledge for a perfect information meld hence objective decision making.In Game Theory, decision making is explained through a set of games. These games give an individual or organisation and nature as players’ choices to affect the outcome. Decision making in an organization responsible for natural resource management hence has to respond to nature’s situation. As an example a decision on harvesting logs for timber must consider the nature of the place of harvesting. Is it a water catchment area? The decision to harvest logs in a water catchment area will affect the water quality of that water. Therefore it is important to consider multiple criteria in making decisions. The task of a decision maker is to design the right combination of the components. To successfully do that the decision maker should either be normative-descriptive or objective-heuristic. Since the nature of the decision to be taken is socio ecological, consider the socio ecological theory belowThis theory places emphasise the close interrelation between biophysical environment and social set up in a human community. The interrelation provides an insight on the consideration of social and ecological interdependency when making decisions to conserve the environment. SES is an old and popular term although still not widely used. The term has grown with the realization that the ecosystems that we may want to protect are embedded in different levels of social organisations and their historical practise. This concern serves to balance the ecological management needs with the welfare of the community. In this case the indigenous knowledge systems which are part of the social organisation should be given attention and be incorporated in the decision making to satisfy the needs of the community. Ostrom argued against the panacea of resource management that neglects the social aspects and focuses on imposing private or government property ownership as a means to conserve resources. Ostrom’s argument insists on the diagnosis of specific problems in the ecological and social context in which they are nested in order to make a management decision. In a nutshell SES calls for the integration of ecology and social context in making decisions on conservation. This aspect of social context can be achieved via the analysis of indigenous knowledge. Analysis of ecosystems can be obtained via geospatial decision support systems. The integration of the two can make a significant platform for decision making in natural resource management.

4.1. Empirical Results from Decision Making Theory

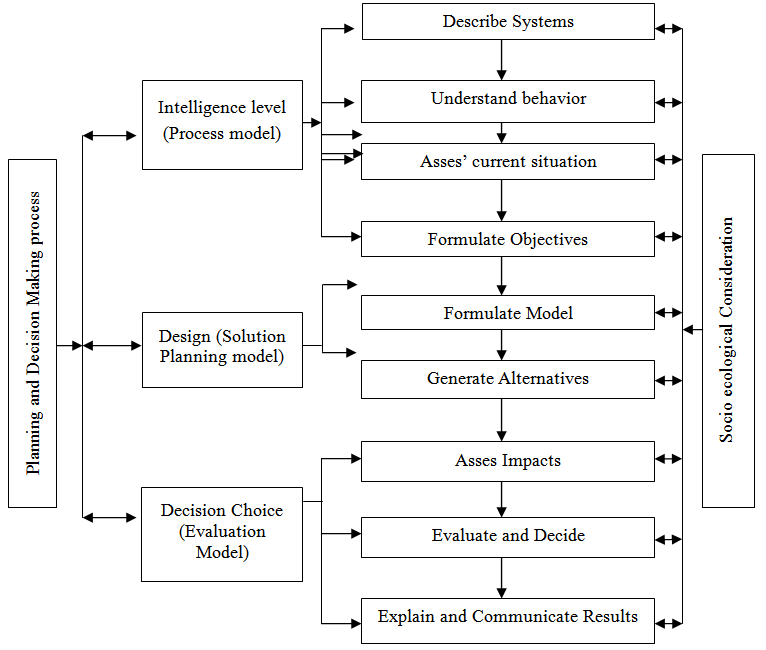

- All these theories have one common end, which contains two aspects, information and alternatives which results from the information. This means that for a decision to be made decision makers have to be informed on the subject matter and the information should be enough to provide decision makers with alternatives. However availability of information alone does not guarantee us with an informed decision; there needs to be a high integration capacity of that information. Human beings lack that capacity hence introducing the need for a support system. It is the requirement of having such information in order to make a decision that calls for the application of remote sensing and geographical information systems capable of capturing, storing, analysing and retrieving data or information to assist decision making. The application of remote sensing and geographical information systems is a result of wanting to undo the uncertainty which decision makers face when trying to choose the best alternative. According to[20] remote sensing and geographical information systems have the capability of aiding decision makers with alternatives which best fits and minimizes the uncertainty. Geographical information systems and remote sensing are not complete in themselves to support decision making but they can form a class of systems within the management information system that supports analysts, planners, and managers in the decision making process termed as GDSS .The central argument of this paper is however not on the capability of GDSS but on integration of GDSS results with IK.This important argument is derived from Social Ecological System (SES) theory wherein IK is the information gained from social organisation. Based on SES theory the integration of geospatial information and indigenous knowledge will make a rational decision making platform for natural resource management. A framework by Turban, which is suggested by this paper as a significant compliment to the suggested integration, provides three major phases important in decision making. Consider the pairing of social ecological system theory in aiding natural resources management decision making with relative reference to[21] framework for planning and decision making. Turban’s framework insists on three phases of decision making process, namely1. Intelligence level (Process model);2. Design (Solution Planning model); and 3. Decision Choice (Evaluation model)

| Figure 1. Turban’s Decision making model/framework Adopted and Modified from: Turban (1995). Modifications to include Socio Ecological Aspects in natural resources decision making |

5. Conclusions and Recomendations

- The need to formulate good regulations for the management of natural resources and to enforce those regulations is strongly reflected in the conclusions of:1. The UN Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Jeneiro, 1992), and;2. The reality that human ecological footprint is exceeding the ecological capacity of the environment.The two have resulted in different natural resources management strategies in the World, Africa and Tanzania in particular. However in practice and in society these strategies have been facing challenges in their implementation. A serious challenge is in the area of decision making. although the use of geospatial information tools makes data manipulation easier hence greatly aiding decision making, decisions on natural resource management are not only dependent on technical geospatial data but other information such as indigenous knowledge is also important. Evidence shows However, indigenous knowledge is rarely incorporated with geospatial data when using geospatial information in the decision making process. A challenge arising from this argument is the possibility of making decisions which do not take into account community needs concerning the resource. Therefore there is a need to integrate indigenous knowledge with geospatial data to aid making decisions in favour of both the local community and the ecosystem. The two arguments uncover the pressing need to improve and regulate management of natural resources particularly at the higher level of decision making. These arguments also serve to improve the appreciation of these two decision making aid tools by comparing and integrating them in order to mitigate the cost of poor natural resource management decisions based on one of the tools only. Geospatial information is more scientific while indigenous knowledge is missing scientific analysed facts. The integration of the two will improve and balance management decisions on the Natural Resource. It will accommodate qualitative dimensions that statistical approaches failed to capture from the community[22]. Moreover, the effective inclusion of indigenous knowledge in planning encourages and facilitates effective community involvement in local decision making. Although the concept of participation and inclusion of indigenous knowledge in planning and decision making manifest itself in urban issues it can also manifest itself in natural resources management issues. The inclusion of indigenous knowledge along with GDSS must be used to improve natural resources management[23].

Notes

- 1. Decision Making is a process of evaluating alternatives and choosing a course of action to solve a problem2. The is a resource accounting tool that helps countries understand their ecological balance sheet and gives them the data necessary to manage their resources and secure their future.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML