-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Ecosystem

p-ISSN: 2165-8889 e-ISSN: 2165-8919

2013; 3(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.ije.20130301.01

Drought Related Impacts on Local People’s Socioeconomic Life and Biodiversity Conservation at Kuku Group Ranch, Southern Kenya

Peter Wangai 1, Joseph K. Muriithi 2, Andreas Koenig 3

1Department of Environmental Studies and Community Development, Kenyatta University, (Mombasa Campus) PO Box 16778-80100, Mombasa, Kenya

2Department of Environmental Studies and Community Development, Kenyatta University, (Main Campus-Nairobi) PO Box 43844-00100 Nairobi, GPO

3Institute of Animal Ecology, University of Technology, Munich Hans-Carls-Von-Carlowitz-Platz, 2 85354, Freising, Germany

Correspondence to: Joseph K. Muriithi , Department of Environmental Studies and Community Development, Kenyatta University, (Main Campus-Nairobi) PO Box 43844-00100 Nairobi, GPO.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The 2009 drought invokes painful memories to pastoralists and conservationists living and working in southern Kenya. The livestock economy predominant in the region was severely affected and wildlife was lost in large numbers. Death of livestock caused meat prices to increase rapidly while nature based tourism revenues decreased significantly due to wildlife deaths. This paper assesses the actual losses of both livestock and wildlife species at Kuku Group Ranch (KGR) during the 2009 drought and the subsequent homegrown socio-economic alternatives to adapt to the drought. The study conducted between late 2009 and early 2010 shows the actual losses for cattle, goats and sheep were significantly high at 84%, 77.8% and 72.8% respectively resulting into huge monetary losses. Key wildlife species central to nature-based tourism such as Zebra (Equus burchelli) and wildebeest (conochaetes taurinus) were severely affected by the drought where they died more than any other wildlife species in the area. The drought increased the livestock and herbivorous depredations by carnivores in the area. The study concludes that despite re-stocking in the case of livestock and re-introduction strategies in the case of wildlife, other sustainable alternatives for adaptation to droughts needed to be integrated to replenish the livestock and wildlife numbers to levels that can ensure stabilizing Maasai people’s livelihoods and also incomes from nature based tourism ecotourism.

Keywords: Drought, Re-stocking, Safety-net, Bio-diversity Conservation, Depredation, Kuku Group Ranch, Southern Kenya

Cite this paper: Peter Wangai , Joseph K. Muriithi , Andreas Koenig , Drought Related Impacts on Local People’s Socioeconomic Life and Biodiversity Conservation at Kuku Group Ranch, Southern Kenya, International Journal of Ecosystem, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2013, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.ije.20130301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Over the last few decades, goats and sheep have formed the largest proportion of Maasai people’s livestock. However, the populations of these domestic animals among the Maasai people of eastern Africa have been declining. Available studies do not explain the reasons for this declining trend in a community whose pastoral and herding culture has survived the influences of 21st C[1]. Over the years, pastoralism has offered a means of livelihoods to 6-10 million people and contributes approximately $10 million to the gross domestic product (GDP) in Kenya[2]. Furthermore, pastoralism contributes to stored wealth in form of livestock in the Arid and Semi-arid Lands (ASALs) at an estimated worth of (USD) $1 billion[3].It has been observed that the formerly predominantly pastoral Maasai community is quickly adoptingagro-pastoral practices[4]. This socio-cultural and economic change has partly been due to encouragement of the community by the government to adopt sedentary lifestyles and also as response to the ecological challenges these regions have been facing. Although recent droughts have played a major role in the dramatic changes in livelihoods of the Maasai people[5], the reactions to these droughts have been totally different to droughts of early 1970s[3]. Over the last two decades, conservation based economic activities such as ecotourism in southern Kenya have also grown significantly[6, 2] but the performance of Maasai pastoralism as a social and an economic system has been on a decline. On the other hand, over the same period, the Maasai people have in various wetlands especially in areas adjacent protected areas such as national parks and game reserves have been adopting agro-practices. This presents a scenario of two competing modes of earning a livelihood and their impacts on Maasai land. Logically, the Maasai should have embraced eco-pastoralism (conservation pastoralism) which is more compatible to the ecological set up of their areas instead of agro-practices such as farming. However, despite adoption of agro-pastoral practices, sustainable food security and sufficiency remains far from being realized. Agro-pastoralism itself remain unreliable as a source of food security due to its susceptibility to ecological challenges such as droughts. The gap between the rich and poor has thus continued to increase among Maasai pastoralists[2] and the government continues to provide relief food to the community during the drought periods. It has been explained that the Maasai are adopting agriculture because of its immediate and direct economic benefits, ready market and low cost of production[4]. It has nothing to do with sustainable production of the crops or better use of land. In the Maasai arid and semi arid lands (ASALs), agriculture in most areas could cause conflicts over water, pasture and space among humans, livestock and wildlife[6, 4]. Documented evidence shows that the cost of converting one hectare of land in ASALs for agriculture is far much greater than the lost pasture because of multiplied and edge effect, blockage of wildlife migratory corridors, fragmentation of habitats, separation of population into sub-populations and degraded soils, hence making it economically non-viable and unsustainable[7].Studies have pointed out that widespread agriculture or more intensive or sedentary forms of animal husbandry are not suited for arid and semi-arid lands[6, 4, 2]. Instead, pastoralism is the most cost-effective venture with minimal ecological effects on ASAL areas and thus best suited to coexist with wildlife conservation. Besides the economic and social parameters playing out in Maasailand, climatic factors like droughts have been a great challenge in the management of pastoralism, wildlife conservation as well as other natural resources in the area[5]. Between 1971 and 2006, the number of people affected by droughts in ASALs has increased from 16,000 to 3.5 million [3]. In the 2009 drought in Kenya, 75% of the total migratory species population and 81% of livestock numbers from pastoralists were lost[8]. Due to the drastic reduction in wildlife populations, revenue from tourism in Kenya was predicted to decline due to strained efforts by tourists to view wildlife attractions in parks. This is due to the fact that, additional time is needed to look and encounter such animals as buffalos as well as increasing fuel consumption within the parks in attempts to look for wildlife. In 2009, 95% of the wildebeest population perished due to drought and by 2010, only 5% was distributed in the Maasai Mara ecosystem and the extended Amboseli-Tsavo-ecosystem[8]. The collapse of the socio-economic base of Maasai livelihood of cattle and the potential threat to endangered wildlife species have been accelerated at the onset of droughts in the area[9]. Most on the areas do not adequately address the ecological based problems that threaten both domestic animals and wildlife that the Maasai people have in the past relied on for livelihoods. Furthermore, coping mechanism to droughts that have been applied fail to meet the new challenges of increased frequency in drought occurrences, rapid socio-economic and long-term climate change impacts[3]. Although the government responds to the ASALs food crisis by distributing relief food, it is only a temporary solution that never makes the communities better economically. Moreover, neither does the adoption of farming in ASALs improve capacity in food sufficiency in the area.This far, few studies have been done to assess the significance of drought on both livelihoods and biodiversity costs among the Maasai people living in southern Kenya. This paper assesses the actual losses of both livestock and wildlife species at Kuku Group Ranch (KGR) in Maasailand, southern Kenya during the 2009 drought and the subsequent socio-economic initiatives undertaken to adapt to the drought. More specifically four issues addressed are: assessment of economic loss livestock through the drought, restocking decisions preferences by the Maasai community at the KGR, economic loss of wildlife in the 2009 drought and alternative sources of incomes available to pastoralists at KGR.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geography and Ecological Character of Study Area

- Kuku Group Ranch (KGR) is found in Kajiado County, southern Kenya and is part of the larger Tsavo Ecosystem. KGR lies between 2-4° South, and 37.2-38.5° East[9]. The total area of KGR is approximated at 1000 square kilometres. However, KGR has an area of 959, 8 km2. 234, 2 km2 (24, 4%) is under human settlements while 725, 6 km2 (75, 6%) comprised of wildlife habitats and grasslands[10]. This land is characterized by alternating flatlands and hills that progressively increase in height as one approach the main Chyullu Hills on the North, and Kilimanjaro on the South.KGR falls under the extensive Tsavo ecosystem that covers an area of 40,000-44,000 square kilometres[9, 8]. The protected area of the ecosystem is 22,000 square kilometres, whereas the rest part is under community and private ranches with diversified economic activities such as farming, pastoralism, ranching and private wildlife sanctuaries. KGR has a share of the extensive volcanic larva rock, famously known as Shetani larva. The eruption that gave rise to the Shetani larva occurred about 200 year ago at Chyullu Hills in the KGR neighbourhood. Nolturesh and Kikarankot rivers traverse through KGR and are the only known permanent rivers in KGR[4]. Other seasonal river include Eeyata, Rombo, Inkisanjani, Naremoru, Masuati, Msangairo and Mokoini. Several springs (Ilchorroi) and wetlands in the area include Meibuko, Chala, Orpakai, Oltinka, Orung'arua and Oltanki Lemasarie. KGR is also characterized by boreholes drilled at strategic places to supplement water demand during the dry seasons. Boreholes are dug mainly for domestic water use but livestock also drink from them in times of drought.In terms of the flora and fauna of the areas, the ecosystem is mainly dominated by Acacia and Commiphora tree species[9]. There are also other common and conspicuous herbs, shrubs and trees in the area. The species include “Grewia spp., Lannea spp., Newtonia hildebrandtii, Premna resinosa, Salvadora persica, Terminalia ssp. and members of the Capparidaceae family, such as Boscia ssp., Cadaba ss. and Maerua. There are also scattered large trees including Adansonia digitata, Balanites aegyptica, Delonix elata, Kigelia africana and Melia volkensii”[9]. Vegetation per se alternates among “wooded-bushland,bushed-grassland and open grassland”[4]. KGR is inhabited by a variety of fauna species. These include the big cat family such as Panthera leo leo, panthera pardus and Acinonyx jubatus. Other common carnivores included Crocuta crocuta, Lycaon pictus, Canis adustus and the rare caracal (Felis caracal). Herbivores occupy the savanna, bush and aquatic habitats of KGR. Examples for savanna herbivore Coke's hartebeest, common wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), bufallo and elands. Bush herbivores include African elephant (Loxodonta africana), giraffe and gerenuk (Litocranius walleri). Hippopotamus are common in the wetlands.

2.2. Sampling, Data Collection and Analysis

- The human population in KGR was not evenly distributed. First, the KGR was divided into eleven zones for easier sampling. Sampling for the eleven zones in KGR was done independently given their uniqueness, variations and discontinuities. Some areas had high population while others were sparsely populated, or without people at all. Where population showed a clustered mode of settlements, random sampling was used to pick interviewees. However, snow-balling method was used to pick samples in cases where population distribution showed high skewness. The sample size for all of the questions ranged between 60 and 124. The differences occurred as a result of the respondent’s “unwillingness to answer” or were unaware of the answer required. Within the total sample size of the area, the proportion of sub-populations in the zones also varied. Data was collected largely through interview schedules: Open-ended and closed questions were set to collect both quantitative and qualitative data about economic status of the Maasai community at KGR, impacts of 2009 drought and the alternative economic activities that the Maasai people were adopting. The interview schedule wastranslated from English to Swahili (the regional linqua franca) and into Maasai language to ease data collection across the different categories of people with different language capabilities. Since most people were not fluent Swahili speakers, the interviews were conducted in Maasai language to capture their most important experiences. Observations and informal group discussions were used to capture the routine life of the Maasai people as well as the community social structure and biodiversity distribution in the area. The discussions were mainly held with Murrans (Maasai youth), Maasai elders/ community chiefs and the Maasai farmers. Informal discussions were aimed at creating friendly relations, which could motivate the target groups to giving out vital information voluntarily. The discussions elicited crucial information on the changing economic behaviour of Maasai. Data analysis was done by categorizing it into quantitative and qualitative data. Descriptive statistics for quantitative data were conducted using MS EXCEL and EVIEWS6.

3. Results and Discussion

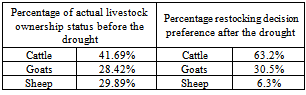

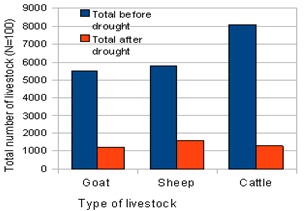

3.1. Economic Loss of Livestock in the 2009 Drought

- The study focused on three types of livestock; goats, sheep, and cattle. There was high disparity in responses collected from the Maasai community and most of the figures provided by them were largely estimates. Therefore, actual numerical values of livestock could not be known because livestock type was taken holistically without categorizing into young ones, mature and the sick. Some respondents could have excluded the young livestock and the sick animals from their proclaimed figures. Hence the total figures given could only be taken as the minimum numbers.

| Figure 1(a). Mean number of livestock per person |

| Figure 1(b). Total number of livestock |

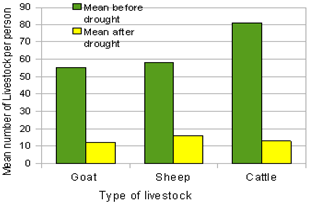

3.2. Livestock Re-stocking Decisions by the Maasai People at KGR

- Restocking is very useful amongst pastoralists after a drought. It helps replenish the livestock lost thus contributing to enhancement of people livelihoods after a period of adversity. In the large Kajiado area, two types of restocking arrangements were observed: internal restocking by the Maasai people themselves and external restocking efforts such as the Kajiado Goats Restocking project of the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), ahumanitarian relief group. In the Kuku Group Ranch, restocking efforts were driven by local efforts. The following table 1 summarises comparativeperspectives relating to actual livestock ownership status before the drought and restocking decision preference after the drought.

|

3.3. Economic Loss of Wildlife in the 2009 Drought

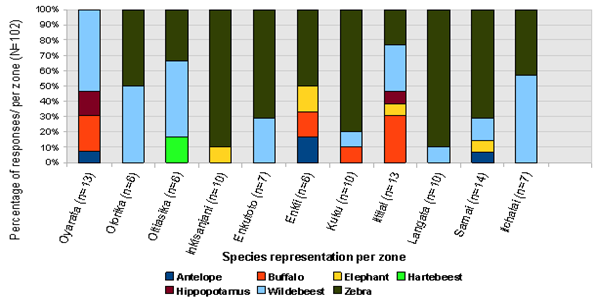

- During the drought, herbivorous species registered the highest death casualty across all zones at the KGR. The figure 2 below shows that zebras were the most affected with a score of 53.9 % of the total responses. In other words, zebra died more than any other species in the area. Wildebeest were the second most affected species by the drought at 26.5 %. These high numbers of herbivores death was also attributed to predation from carnivores. Their combined death rate was massive and occurred to huge economic losses for the ecotourism sub-sector in the area since these are some of the tourist attractions in group ranches. The losses had subsequent livelihoods and other social economic impacts on the community for much of this area since they could not derive tourism benefits especially through the different tourism benefit sharing arrangements such as land lease mechanisms from tourist operators and wildlife viewing as well as direct final benefits from the business of tourism taking place in their ranches. Overall, such multiplied pressure leads to increased resistance from the community in setting conservancies and migratory corridors for wildlife species.

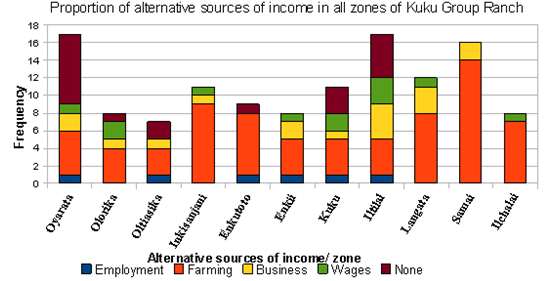

3.4. Alternative Source of Income from the Predominant Pastoralism at Kuku Group Ranch

- With impacts of drought taking a toll on the core livelihood means of pastoralism as well as on tourism, the Maasai people remained constrained on alternatives to earn incomes to help overcome the socio-economic impacts of the drought. Therefore, few residents (respondents) gave more than one alternative source of income. Farming was the most mentioned alternative source of income at 55%. This is well over half of the residents of the ranch and it points at the general trend in terms of preference of alternative to pastoralism in the area. Actually, over the last two or so decades, more and more Maasai pastoralist in the larger Kajiado zones have been adopting farming[4], especially with more interactions with farming communities like the Kamba and Kikuyu who have migrated and settled in the area[11, 12]. A significant number (16%) had no alternative source of income. It means they purely relied on pastoral herding in eking their livelihoods. 14% of the residents were engaged in business opportunities. Part of the business entailed selling the livestock that had managed to overcome drought especially to the Kenya Meat Commission (KMC) near Nairobi. Wage employment capturing 15% of the suggested alternative source of income was significant and it came from assorted activities such as business, farming as well as wage employment in various towns in the region. In sum, there is high overall dependence on farming compared to other alternatives to pastoralism. In ecological terms, there is no sustainability of farming activities in the area. This is due to the average diurnal and annual humidity, soil quality and temperature variability. Sustainable resource management in the area should aim at more investments on ecological businesses. Projects in bee-keeping,ethno-botany and trade seemed socially and ecologically viable in the area. Figure 3 indicates disparity in the alternative sources of income in the eleven zones of KGR. The reasons for the zonal disparity included but not limited to proximity to urban centres, proximity to National parks, distribution of social amenities and natural water bodies.

| Figure 2. Herbivorous species reported to have died in 11 zones at KGR during the 2009 drought |

| Figure 3. Proportion of existing alternative sources of income in each zone of Kuku Group Ranch (N=124) |

4. Conclusions

- Droughts remain a major threat to socio-economic stability of the Maasai pastoralists. The increasing adoption of farming activities by Maasai at KGR is an attempt to fill the livelihood gaps and options caused by the frequently occurring droughts. With high drought frequency and limited mitigation and adaptation measures to the impacts of climate change, diversifying sources of income and livelihood sources aims at reducing the risk factor to the Maasai pastoralists at KGR. As competition for resources between livestock and wildlife become stiff, it will be easier for wildlife to be viewed as a liability rather that an asset. This has implications on attempts especially by the government to convince the pastoral Maasai to adopt such activities as ecotourism which are locally thought to be difficult to undertake especially due to the high capital outlays required for initial investments as well as lack of capacity to run successful tourism businesses. This study reveals two reasons for this likelihood. First it’s due to perceived low economic benefits from ecotourism and, secondly due tonon-responsive management strategies of both livestock and wildlife resources in the area. Therefore, this analysis is in agreement with other studies such as Okello[4] that Maasai pastoralists would continue striving to attain food security and poverty alleviation by adopting locally and less costly measures available to them. Furthermore, to this community, keeping large herds of livestock and subsistence agriculture is meant to distribute risk, offer safety nets, insurances, and to cushion them against the frequent severe droughts and livestock disease and climate variability[1]. This study proposes establishment of an appropriate ecological economic system in the area that goes beyond mare re-stocking and re-introduction of livestock and wildlife respectively. Further research is needed to ascertain the seemingly high potential for apiculture, ethno-medicine, education, culture and heritage as ecological economic projects in the area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to acknowledge the following institutions for various kind of support. The Katholischer Akademischer Ausländer Dienst (KAAD) for major funding of this study and Techniche Universität Munchen (University of Technology Munich) in Germany for minor funding. The Maasai Wilderness Conservation Trust (MWCT) and the Maasai community at Kuku Group Ranch, Kenya for providing logistical support during field work.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML