-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

p-ISSN: 2332-8355 e-ISSN: 2332-8371

2021; 8(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.ijcp.20210801.01

Received: Jan. 17, 2021; Accepted: Feb. 5, 2021; Published: Feb. 26, 2021

Risk Factors Associated with Psychiatric Comorbidities Among Suicide Attempters

Yadav Tarun1, Gupta Prerana2, Nagendran S.2, Puri Arnav1

1Post Graduate Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College & Research Centre Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India

2M.D, Professor in Department of Psychiatry, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College & Research Centre Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India

Correspondence to: Gupta Prerana, M.D, Professor in Department of Psychiatry, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College & Research Centre Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

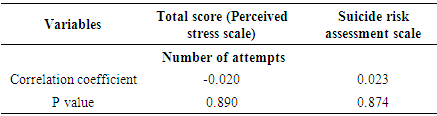

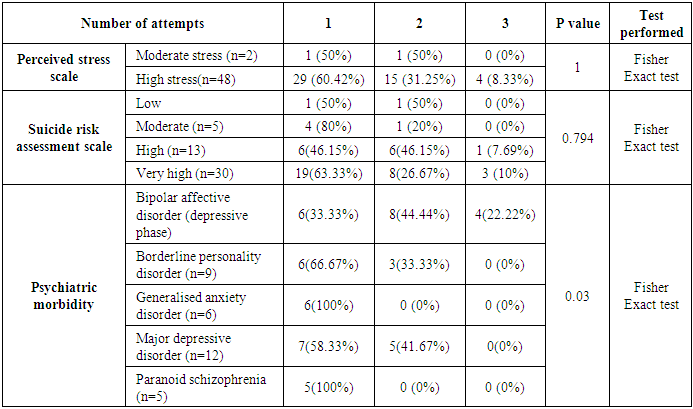

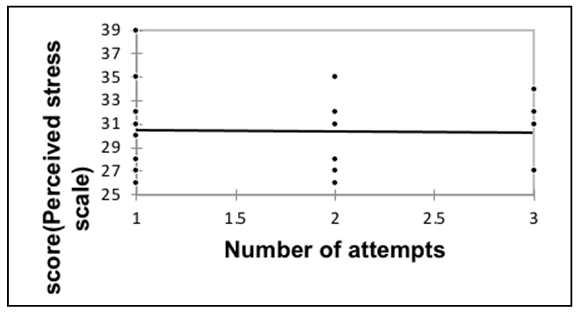

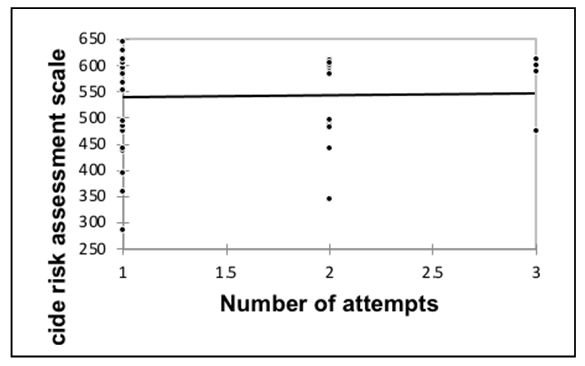

Context: Suicide is one of the leading causes of mortality in developed world with loss of more than one lakh lives in India. The suicidal behavior of an individual remains complex and challenging to be predicted, with few established risk factors. Aims: We aimed to describe socio-demographic characteristics and identify associative risk factors and psychiatric comorbidities among suicide attempters. Settings and Design: The present study was an observational cross-sectional study on 50 patients who presented to the psychiatry department with suicide attempts. Materials and Methods: Socio-demographic details and suicide specific details were recorded using a self-structured Performa and risk for suicide was calculated using the California Risk Assessment for suicide Scale (CRAS). Level of stress in the patients were evaluated using Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and Psychiatric comorbidity was assessed using Standard Diagnostic interview as per ICD 10. Statistical analysis: The comparison of quantitative variables was done through Independent t Test (for two groups) and ANOVA (for more than two groups) and for qualitative variables was done by using Fisher’s Exact test. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation of total score and suicide risk assessment scale with number of attempts. For statistical significance, p value of less than 0.05 was considered as significant. Results: The mean age of study patients was 23.76 ± 6.8 years with M:F of 0.94:1. Majority were Hindu by religion (70%), residing in rural areas (70%) were unmarried (54%) well educated (>70%), unemployed (70%), living in nuclear family (68%) with a socio-economic status of I in 72% cases. None of the socio-demographic factors showed a significant association with suicide risk. The suicide risk was very high, high, moderate and low in 60%, 26%, 10% and 4% respectively; with 60% being first time attempters and 40% re-attempters. Number of suicide attempts was significantly higher (>1) in Bipolar affective disorder as compared to other psychiatric morbidity (p<0.05). The type of attempt was hanging (52%) with significant association with high risk suicide and organo Phosphate Poisoning (32.00%) which was associated with low-moderate suicide risk with others such as cutting arm with sharp objects and drug overdose in 4 cases of moderately perceived stress (p<.05). Conclusion: In conclusion, suicide attempts are common in young population with female predominance. The persons committing suicide attempts are predominantly less educated, belong to a lower socio-economic class, reside mainly in rural areas and have a less monthly income. The family structure of such individuals show that both single or married and varied family size are prone to suicide risk. The birth order of second or more carry an additional chances of suicide attempts. The suicide attempters have plethora of psychiatric comorbidities which may be the underlying cause of their increased attempts, however this association needs to be explored in the future studies. Hanging as a mode of suicide attempt is significantly associated with a high risk behavior of suicide attempt.

Keywords: Bipolar affective disorder, Psychiatric comorbidity, Suicide attempt

Cite this paper: Yadav Tarun, Gupta Prerana, Nagendran S., Puri Arnav, Risk Factors Associated with Psychiatric Comorbidities Among Suicide Attempters, International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2021, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcp.20210801.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Suicide attempt, a “self-harm behavior with an intent to die” is a recurring problem and is more frequent than completed suicides. The suicidal behavior of an individual remains complex and challenging to be predicted [1].Suicide is a cause of concern in the emerging phenomenon of new era where new methods for suicide are on rise and contributing to overall increase [2]. Around 793824 deaths occurred globally in the year 2017 with rate of 10.4 per 1,00,000 by suicide [3]. Suicide is the leading cause of death among the age group of 15-29 years. Deaths due to suicide are maximum (75.5%) in low and middle income groups (LMIC), in countries around the world. India’s contribution towards suicide deaths occurring globally is 26.6% [3,4]. In all state groups of India suicide was one of the leading cause for the loss of life [5]. In India during 1990 – 2016 suicide also played its role among disease burden [5]. Rate of suicide increased from 25.3% to 36.6% from 1990- 2016 among women, and among men from 18.7% to 24.3% [6]. India’s role in achieving the sustainable development goals (SDG’s) that target a reduction in premature mortality by third from non-communicable diseases by 2030 with suicide mortality rate as one of the key indicators leading to global implication for suicide due to its huge population [7].The suicidal act is personal and private, still a wide range exits across different places. A bigger picture of understanding for region -specific suicide is needed to enable prevention strategies that would be culturally specific [8,9]. WHO recommended that understanding and identifying about suicide is a key component for all the strategies that are inclusive for the prevention of suicide [4]. The history of attempted suicide is one of the important estimator for the future suicide risk [10-12]. Lethality of the suicide attempt tends to increase with the recurrence of the attempt [13]. Within 5 years of duration of the last attempt almost half the patients tend to do the repetition [14], making risk of completion of suicide much higher than the general population. Thus monitoring of suicide attempters becomes much essential to restrict suicide behaviors [15].Other lifestyle factors such as unemployment, marital status (divorce, single), and education also holds importance in predicting the suicidal behaviour. In addition, many people who commit suicide have experienced major depression [16]. Large community studies have evidenced association of multiple lifetime mental disorders and psychiatric comorbidities among suicide attempters [17,18]. There is a dearth of studies focusing on suicidal behavior, risk factors, association of suicidal risk with psychiatric comorbidity and future suicidal risk in such patients, in this part of the country. Keeping in mind the vast number of psychiatric referrals to the psychiatry OPD from medical, surgical and burn Intensive care units and other departments for suicidal attempts, the following study is planned.

2. Aims and Objectives

- The present study was conducted with an aim to evaluate the socio-demographic characteristics of the suicide attempters and identify associative factors and psychiatric comorbidities among them.

3. Materials and Methods

- An observational cross-sectional study was conducted on 50 patients aged 18 years and above of either gender, who presented to the psychiatry department with suicide attempts from the period of January 2019 to June 2020. We excluded the patients (1) who were unstable, unco-operative, unresponsive, or on ventilator (2) giving history of deliberate self-harm but with no specific intention for suicide and (3) suffering from Mental Retardation or any organic brain disease. A written informed consent was obtained from the patients before enrolling them into the study. The study was formally approved by the institutional ethical committee.The sample size was based on the study of Subramanian K, et al [19] who observed that depression was significant risk factor of suicide attempt with odds ratio of 6.88. Taking these values as reference, the minimum required sample size with 80% power of study and 5% level of significance is 45 patients. To reduce margin of error, total sample size taken is 50.Socio-demographic details and suicide specific details were recorded using a self-structured Performa and risk for suicide was calculated using the California Risk Assessment for suicide Scale (CRAS). Level of stress in the patients were evaluated using Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and Psychiatric comorbidity was assessed using Standard Diagnostic interview as per ICD 10. The association between various socio-demographic factors, number of attempts, type of attempts, psychiatric comorbidities and risk of suicide was determined. P<0.05 was considered as significant.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

- The collected data was entered in Microsoft EXCEL spreadsheet and analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software ver 21.0.The comparison of quantitative variables was done through Independent t Test (for two groups) and ANOVA (for more than two groups) and for qualitative variables was done by using Fisher’s Exact test. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation of total score and suicide risk assessment scale with number of attempts. For statistical significance, p value of less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

4. Results

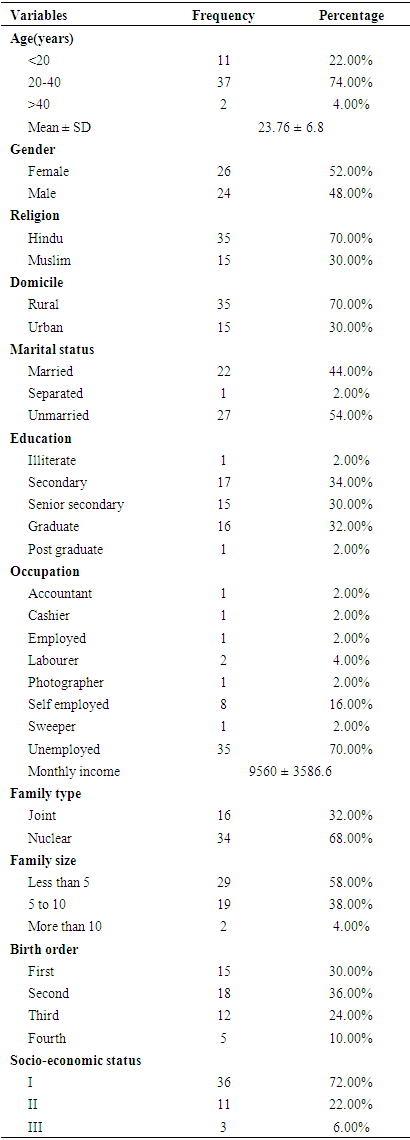

- Mean value of age (years) of study subjects was 23.76 ± 6.8 years with M:F of 0.94:1. Majority were Hindu by religion (70%), residing in rural areas (70%) and were unmarried (54%). The education levels showed that 34% studied till secondary and 32% were graduates, however most of them were unemployed (70%) with a mean monthly income of Rs 9560 ± 3586.6. The family type was nuclear in 68% cases with a socio-economic status of I in 72% cases. The family size was less than 5 in 58% subjects. Around 66% of the patients had first or second birth order. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of study subjects.

|

| Figure 1.1. Correlation of number of attempts with total score (Perceived stress scale) |

| Figure 1.2. Correlation of number of attempts with suicide risk assessment scale |

|

|

5. Discussion

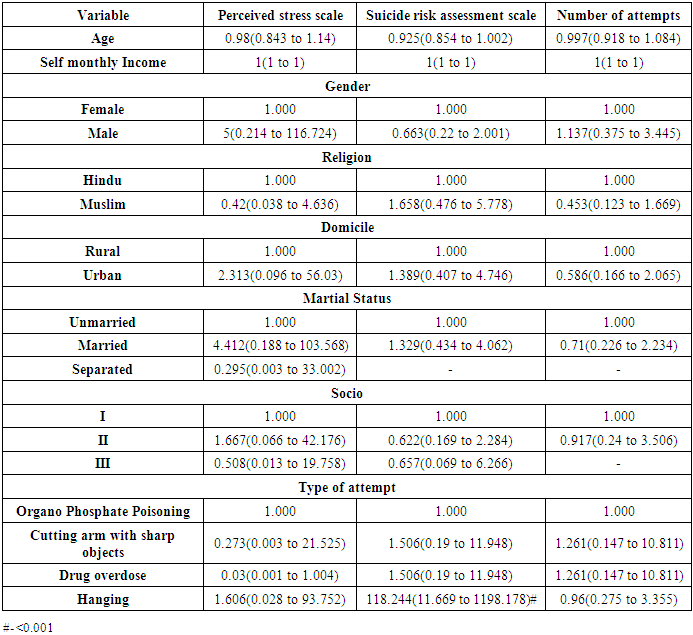

- This is one of the first large Indian studies to report psychiatric comorbidities among suicide attempters. In our study, 36% had bipolar affective disorder (depressive phase) followed by major depressive disorder (24.00%), borderline personality disorder (18.00%), generalized anxiety disorder (12.00%) and paranoid schizophrenia (10%). This was in line with the study by Sahoo MK et al [1], where the percent of psychiatric diagnosis in Suicide attempters was around 70% with depressive disorders being the most common and least common being adjustment disorder, substance abuse and anxiety disorder. The association with bipolar disorder was reinstated in a study conducted on 102 BPD patients (males = 49 and females = 53) which showed that presence of an index depressive episode (OR: 6.88, 95% CI: 1.70–27.91, p = 0.007) was associated with suicide attempts as was seen in the present study [19].We found that patients with BPD (depressive phase) had significantly higher number of attempts as compared to those with other psychiatric disorders. In comparison to this, Park S et al [20], (2018) found that in OCD, Anxiety disorders, depressive disorders the relative risk was significantly higher as compared to moderate and low risk attempters. Depression and hopelessness were also found to be precipitating factors in the study by Salman S et al [21]; the reason being the person may want some attention and this also corroborates with high female suicide attempts as they have more depression. In a case-control study by Bhatt M et al, [22] which determined the risk profile of Suicide attempts in psychiatric patients, it was seen that impulsivity (odds ratio [OR] = 1.15, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.03–1.30) and borderline personality symptoms (OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 1.01–1.13) were significantly associated with attempted suicide. Parra-Uribe I et al, [23] further showed that cluster B personality disorders (36.8% vs. 16. 6%; p < 0.001), and alcohol use disorders (19.8 vs. 13.9; p = 0.02) are significantly associated with increasing suicide attempts. Besides, it has been observed in studies that medically unexplained physical pain and somatoform disorder are significantly related to suicidal behaviour and suicidal ideation [24,25]. Although they have gained relatively less attention, individuals with this disorder (somatoform ) have believed that physical pain would not improve and so may attempt suicide to get relieve from distress associated with physical concern and hopelessness [25].An interesting observation in our study was that hanging was the commonest method of suicide attempt and it associated with an increased risk of suicide attempts (OR=118.244, p<0.05). One of the reason for more cases of hanging in our study could be because of more rural population where the residence providing easy availability of ropes, trees and fans for hanging [26]. This also suggests that once the stress levels are high and risk of suicide is high, one searches for the easiest, quickest and affordable way of suicide, which is hanging where the material requires is rope and a roof to hang. Besides, Suicide is a private and personal act and the use of ropes, sharp objects and drugs in personal space of home without anybody’s help increases the use of these methods in most of the suicide attempts. Studies corroborate with the fact that in rural areas the readily available ropes and agricultural pesticides make it easy for attempting suicide by hanging and consumption of pesticides respectively as was seen in our country [27]. However in the urban areas, the mode of Suicide attempts is mainly consumption of toxins such as phenyl consumption and general medication lying at home [1]. Overall this association has not been explored much in the previous studies and may need future validation in larger subset of suicide attempters.In present study, 60% were first attempters and 40% were re-attempters among which 32% did their second attempt and 8% had their third attempt. The re-attempts showed significant association with psychiatric co-morbidities. The findings were in line with the study by Parra-Uribe I et al, [23] where alcoholism and personality disorders were significant risk factors for reattempts. They also showed that increasing age is a protective factor for re-attempts but that association was not seen in the present study. Follow up studies have shown that the increasing number of attempts are more in the initial 2 years of the first attempt, [23] an association that could not be determined in our study owing to the cross-sectional study design. The fact needs to be stressed here that the high risk attempters become habitual with each repeated process of suicide attempt and their suicidal behaviour becomes chronic with increase tolerance and decreased fear of death, thereby necessitating the need to counsel such suicide attempters to prevent future attempts [28].Even the underlying socio-demographic factors affect the suicide attempts. Literature reports that Suicide attempts shows a preponderance in the younger age groups [29]. In the present study, majority (74%) of the suicide attempters belonged to age group 20-40 years and 22% were <20 years of age, with a mean age of 23.76 ± 6.8 years. Our findings were in line with the study by Sahoo MK et al [1] where 61% of attempters belonged to the age group between 20 and 40 years and 32% were <20 years of age. In the study by Salman S et al, [21] 23.3±10.2 years (n=45) was the mean age group which was comparable to our study. Majority of the suicides in these age groups denote that the most productive age groups is being at risk and imposes a huge social, emotional, and economic burden on society [1]. This may be indicative of increasing stress levels in the young age group at the level of society on various aspects such as income, employment and social status [20].The index study showed slight female preponderance (52% females and 48% males) with a M:F of 0.94:1. This was comparable with another study done in Tata hospital Jamshedpur, India where there were 42 males and 59 females with a M:F of 1:1.4.59 The findings were also similar to a study done in Pakistan on 45 cases where 25 were females and 20 were males; 61 and Sharma B et al, [30] study which was done on school going students in Peru who reported 53.6% girls among the total sample of 916 students [30]. This corroborates with the reports at global level which shows that cases of completed suicide is more in Men whereas attempted suicide is more in Women [31]. Increase number of cases of depression in women could be one reason [23]. Another reason for increased Suicide attempts among females is staying in abusive marriages. Further, the study population mainly resided in rural areas where such practices are more prevalent, amounting for increased Suicide attempts among females.Persons living alone are at particular risk [32]. However, in our study, it was common to find a larger number of attempters being married as well. This was similar in line with the reports of Sahoo MK et al, [1] where married attempters constituted around 43% and singles constituted to be 52.5%; and Salman S et al, 61 where 33.3% were married and 66.7% were single. The increased Suicide attempts among separated or widowed has been well proven in Western studies [33]. however the increasing Suicide attempts in married individuals may be subjected to the role of various other risk factors like perceived stress in the life and accompanying psychiatric co-morbidities. This can be said because recently, a study conducted in Canada [23] also found high proportion of married individuals in stable relationships had attempted suicide; however the figures did not reach statistical significance (p>0.05).In the present study, the education levels showed that 34% studied till secondary and 32% were graduates, however most of them were unemployed (70%) with a mean monthly income of Rs 9560 ± 3586.6. The overall socio-economic status of study population was I in majority (72%) of the cases. Current study results and literature review shows that education and employment holds no statistical association with Suicide attempts or reattempts [23].With changing world, The individuals are preferring for a nuclear family because most of them are away from their parents for employment or education.In our study, majority of the participants were from nuclear family (68%) with few from joint family (32%). The findings were comparable to the study by Sahoo MK et al, [1] where 60% were from nuclear family and 40% were from joint family. The decreasing social support in nuclear families may form one of the factors causing stress among the individuals. Also the financial stature of the family is lowered as the earning members of the family are decreased. One of the study by DeVille et al, [34] reinforced that family factors, such as family conflict and low parental monitoring may increase the suicidal ideation and attempts since early childhood making them more prone to reattempts in the adulthood. All these factors suggest that family type and parental relations in the family carry a major role in the person’s ideation and Suicide attempts.It has been observed that birth order has an association with increased risk of suicide as is seen in varying cultures and family size and design with every increase in birth order an increase of 18-46% of risk is seen [35]. Theoretically it has been noted that if the risk associated with later birth order could be removed, then there is potentially 24% of chance to prevent suicide. It has been observed that (PAF=0. 24) that is Population Attributable Factor is high for the contribution of birth order [36].Even in our study we found that only 30% of the Suicide attempters were first born and rest of the 70% were second or more in birth order. (36% second, 24% third and 10% fourth in birth order) suggesting that Suicide attempts were more with >1 birth order. The findings were in line with the study by Easey et al, [37] (n = 2571), who directly showed that increase risk of suicide attempts would increase with high birth orders (OR = 1.42, CI = 1.10–1.84). However, the increased risk of suicide with birth order must be weighed against the confounding factors which include gender, age, education, family size and parent’s mental health. Even in our study we found that family size was upto 5 in 58% cases and >5 in 42% cases indicating large family’s despite being nuclear, thus adding to the increased stress levels for the managing parents and creating a disharmony in the family. Further, paternal absence and psychiatric co-morbidities such as maternal depression may also partially mediate the associations between birth order, and suicidal behavior [37]. Future studies should investigate these confounding factors and alternative mediating pathways involved in the risk associated with family size, birth order and Suicide attempts.The strengths of the study were that it was restricted to the serious suicide attempts which needed hospital admission and thus the results add to the data of the socio-demographic profile and associating factors in this subset of population. The study helps provide additional data about the associated psychiatric comorbidities and its association with suicide attempts. However, the study was limited by the fact that the suicide risk assessment was on a subjective basis which may cause a bias while determining the association of suicidal risk and socio-demographic factors.

6. Conclusions

- In conclusion, suicide attempts are common in young population with female predominance. The persons committing suicide attempts are predominantly less educated, belong to a lower socio-economic class, reside mainly in rural areas and have a less monthly income. The family structure of such individuals show that both single or married and varied family size are prone to suicide risk. The birth order of second or more carry an additional chances of suicide attempts. The suicide attempters have plethora of psychiatric comorbidities which may be the underlying cause of their increased attempts, however this association needs to be explored in the future studies. Hanging as a mode of suicide attempt is significantly associated with a high risk behavior of suicide attempt.Practical recommendations based on results: Suicide attempters must be counselled and assessed for the stress levels in their daily life and the concurrent psychiatric disorders. It must be taken care by the family members that they avoid any nearby use of ropes or other hanging materialas and unprescribed purchase of medications and drugs. Patients with Borderline personality disorders must be closely monitored as they carry a significantly high risk of subsequent suicide attempts.

References

| [1] | Sahoo MK, Biswas H, Agarwal SK. Risk factors of suicide among patients admitted with suicide attempt in Tata main hospital, Jamshedpur. Indian Journal of Public Health (2016) 60:260–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-557X.195853. |

| [2] | Rajagopal S. Suicide pacts and the internet. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) (2004) 329: 1298–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7478.1298. |

| [3] | Institute for health metrics and evaluation. GBD results tool. Global health data exchange. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool (accessed February 26, 2019). |

| [4] | Saxena S, Krug E C. Preventing suicide: A global imperative. 2014. |

| [5] | Dandona L, Dandona R, Kumar GA, Shukla DK, Paul VK, Balakrishnan K, et al. Nations within a nation: variations in epidemiological transition across the states of India, 1990–2016 in the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet (2017) 390: 2437–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32804-0. |

| [6] | India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Suicide Collaborators: Rakhi Dandona, G Anil Kumar, R S Dhaliwal, Mohsen Naghavi, Theo Vos, D K Shukla, Lakshmi Vijayakumar, G Gururaj, J S Thakur, Atul Ambekar, Rajesh Sagar, Megha Arora, Deeksha Bhardwaj, Joy LD. Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2016. The Lancet Public Health (2018) 3:e478–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30138-5. |

| [7] | No TiUN Department of economic and social affairs. Sustainable development Goal 3: ensure healthy lives and promote well – being for all at ages. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3 (accessed February 4, 2019). |

| [8] | Birbal R, Maharajh HD, Birbal R, Clapperton M, Jarvis J, Ragoonath A, et al. Cybersuicide and the adolescent population: challenges of the future? International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health (2009) 21:151–9. |

| [9] | Thomas K, Chang S Sen, Gunnell D. Suicide epidemics: The impact of newly emerging methods on overall suicide rates - A time trends study. BMC Public Health (2011) 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-314. |

| [10] | Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: a 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (2000) 68: 371—377. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.68.3.371. |

| [11] | Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science (1997) 170: 205–28. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.170.3.205. |

| [12] | Gururaj G, Isaac MK, Subbakrishna DK, Ranjani R. Risk factors for completed suicides: a case-control study from Bangalore, India. Injury Control and Safety Promotion (2004) 11: 183–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/156609704/233/289706. |

| [13] | Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TEJ. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review (2010) 117: 575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697. |

| [14] | Beautrais AL. Further suicidal behavior among medically serious suicide attempters. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior (2004) 34: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.34.1.1.27772. |

| [15] | Tidemalm D, Långström N, Lichtenstein P, Runeson B. Risk of suicide after suicide attempt according to coexisting psychiatric disorder: Swedish cohort study with long term follow-up. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) (2008) 337:a2205. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a2205. |

| [16] | Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, Herrmann JH, Forbes NT, Caine ED. Relationships of age and axis I diagnoses in victims of completed suicide: a psychological autopsy study. The American Journal of Psychiatry (1996) 153: 1001–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.153.8.1001. |

| [17] | Gili M, Castellví P, Vives M, de la Torre-Luque A, Almenara J, Blasco MJ, et al. Mental disorders as risk factors for suicidal behavior in young people: A meta-analysis and systematic review of longitudinal studies. Journal of Affective Disorders (2019) 245: 152–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.115. |

| [18] | World Health Organisation and others. National suicide prevention strategies: progress, examples and indicators 2018. |

| [19] | Subramanian K, Menon V, Sarkar S, Chandrasekaran V, Selvakumar N. Study of Risk Factors Associated with Suicide Attempt in Patients with Bipolar Disorder Type I. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice (2020) 11: 291–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1709347. |

| [20] | Park S, Lee Y, Youn T, Kim BS, Park JI, Kim H, et al. Association between level of suicide risk, characteristics of suicide attempts, and mental disorders among suicide attempters. BMC Public Health (2018) 18: 477. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5387-8. |

| [21] | Salman S, Idrees J, Hassan F, Idrees F, Arifullah M, Badshah S. Predictive Factors of Suicide Attempt and Non-Suicidal Self-Harm in Emergency Department. Emergency (Tehran, Iran) 2014; 2: 166–9. |

| [22] | Bhatt M, Perera S, Zielinski L, Eisen RB, Yeung S, El-Sheikh W, et al. Profile of suicide attempts and risk factors among psychiatric patients: A case-control study. PloS One (2018) 13:e0192998. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192998. |

| [23] | Parra-Uribe I, Blasco-Fontecilla H, Garcia-Parés G, Martínez-Naval L, Valero-Coppin O, Cebrià-Meca A, et al. Risk of re-attempts and suicide death after a suicide attempt: A survival analysis. BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17: 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1317-z. |

| [24] | Park S, Cho MJ, Seong S, Shin SY, Sohn J, Hahm B-J, et al. Psychiatric morbidities, sleep disturbances, suicidality, and quality-of-life in a community population with medically unexplained pain in Korea. Psychiatry Research (2012) 198: 509–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.01.028. |

| [25] | Wiborg JF, Gieseler D, Fabisch AB, Voigt K, Lautenbach A, Löwe B. Suicidality in primary care patients with somatoform disorders. Psychosomatic Medicine (2013) 75: 800–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000013. |

| [26] | Radhakrishnan R, Andrade C. Suicide: An Indian perspective. Indian Journal of Psychiatry (2012) 54: 304–19. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.104793. |

| [27] | Srivastava MK, Sahoo RN, Ghotekar LH, Dutta S, Danabalan M, Dutta TK, et al. Risk factors associated with attempted suicide: a case control study. Indian Journal of Psychiatry (2004) 46: 33–8. |

| [28] | Joiner T. Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press; 2007. |

| [29] | Arun M and Yoganarasimha, K and Palimar, Vikram and Kar, Nilamadhab and Mohanty MK. No TitlePara suicide - An approach to the profile of victims. Journal of Indian Academy of Forensic Medicine (2004) 26: 58–61. |

| [30] | Sharma B, Nam EW, Kim HY, Kim JK. Factors Associated with Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt among School-Going Urban Adolescents in Peru. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (2015) 12: 14842–56. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121114842. |

| [31] | Phillips MR, Yang G, Li S, Li Y. Suicide and the unique prevalence pattern of schizophrenia in mainland China: a retrospective observational study. Lancet (London, England) (2004) 364: 1062–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17061-X. |

| [32] | Schmidtke A, Bille-Brahe U, DeLeo D, Kerkhof A, Bjerke T, Crepet P, et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989-1992. Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica (1996) 93:327–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10656.x. |

| [33] | Vijayakumar L, John S, Pirkis J, Whiteford H. Suicide in developing countries (2): risk factors. Crisis (2005) 26:112–9. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.26.3.112. |

| [34] | DeVille DC, Whalen D, Breslin FJ, Morris AS, Khalsa SS, Paulus MP, et al. Prevalence and Family-Related Factors Associated With Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Attempts, and Self-injury in Children Aged 9 to 10 Years. JAMA Network Open (2020) 3: e1920956. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20956. |

| [35] | Bjørngaard JH, Bjerkeset O, Vatten L, Janszky I, Gunnell D, Romundstad P. Maternal age at child birth, birth order, and suicide at a young age: a sibling comparison. American Journal of Epidemiology (2013) 177: 638–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt014. |

| [36] | Riordan D V, Selvaraj S, Stark C, Gilbert JSE. Perinatal circumstances and risk of offspring suicide. Birth cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science (2006) 189: 502–7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.015974. |

| [37] | Easey KE, Mars B, Pearson R, Heron J, Gunnell D. Association of birth order with adolescent mental health and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2019) 28:1079–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1266-1. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML