-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

p-ISSN: 2332-8355 e-ISSN: 2332-8371

2019; 7(1): 23-34

doi:10.5923/j.ijcp.20190701.04

Attitude of Second Year Medical Students towards Psychiatry Studying in a Private Medical College in Western Uttar Pradesh

1Post Graduate Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad

2Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad

Correspondence to: Gupta Prerana, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

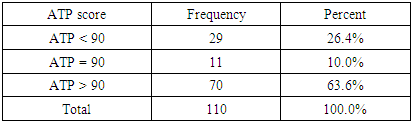

Context: Both psychiatry as a specialty and mental illnesses carry a lot of stigmatizing attitudes. Even medical professionals are not immune to prevailing stigma. Psychiatrists are perceived to have less scientific attitude, earn less money, to be less respected, and to have less prestige. Aims: The present study was designed to know the attitude of medical students with exposure to medical education, toward psychiatry as a specialty. Settings and Design: The study was conducted at Teerthanker mahaveer medical college, Moradabad. The study was done among 110 second year medical students. Materials and Methods: Self-administered sociodemographic and Attitude Toward Psychiatry-30 items questionnaire were given to the second-year medical students after a psychiatry lecture. Consent was taken individually from all the 2nd year medical students (total=150), out of which 40 students refused to give the consent. The questionnaire was explained in detail to the rest of the 110 students and the scores were analyzed using appropriate statistical tools. Statistical Analysis Used: unpaired t-test, one-way ANOVA test with post-hoc bonferroni test, Chi- square test using SPSS version 21. Results: nearly 63.6% of second year medical students had positive attitude toward psychiatry (chi-square value = 0.313, p=0.855). Only 22.7% second-year students affirmatively indicated to choose psychiatry as a career choice while 24.5% denied choosing psychiatry as a speciality and 52.7% had neutral attitude toward choosing psychiatry. Conclusions: There was no significant difference in distribution of ATP score between males and females. Despite all the stigma towards psychiatry our students had more positive attitude toward psychiatry. The most positive responses were received in the items such as “ psychiatric illness deserve at least as much attention as physical illness”, “psychiatry is a respected branch of medicine”, psychiatric hospitals have a specific contribution to make to the treatment of the mentally ill “, “in recent years psychiatric treatment has become quite effective”, psychiatry is the most important part of the curriculum in medical schools” and “ if we listen to them psychiatric patients are just as human as other people”.

Keywords: Attitude, Psychiatric hospital, Psychiatric illness, Psychiatrist, Stigma

Cite this paper: Singh Shweta, Gupta Prerana, Attitude of Second Year Medical Students towards Psychiatry Studying in a Private Medical College in Western Uttar Pradesh, International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2019, pp. 23-34. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcp.20190701.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- For two decades, there has been growing worldwide concern that psychiatry as a profession, its identity, and image is in crisis [1–4]. Moreover, there is an imbalance between the high numbers affected by mental disorders [5–7], the high and increasing worldwide burden attributable to mental disorders in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), years of life lost to premature mortality (YLL) and years lived with disability (YLD) [8], and the declining numbers of young academics choosing psychiatry as a career [4,9–13].In order to learn more about medical students’ views of psychiatry, numerous studies have focused on their attitudes toward psychiatry and their intended or de nite career choice in order to obtain a deeper insight into the factors which might contribute to a better standing [14–25]. Most studies indicate a discrepancy between positive attitudes toward psychiatry and low willingness to work in the field [14,17,18].In particular, medical students acknowledge the value of psychotherapy [17], view psychiatry as intellectually challenging and personally rewarding, but are reported to entertain a certain skepticism toward factors such as scientific standing, status, prestige and financial prospects, psychiatrists, patients, and treatment [14].As a specialization of choice, psychiatry has not been looked up to in the same breath as that of other clinical subjects. It continues to struggle with its negative image which results in reduced postgraduate recruitment rates in developed and developing countries. [26,27]Existing stigma and negative attitude affects not the patient care only but choosing psychiatry as career option by medical students as well. Most medical students consider psychiatry an unrewarding and a stressful specialty [28]. Stigma attached to psychiatric illnesses is also reflected by the fact that very few among the doctors prefer to specialize in psychiatry and even familial pressure against the psychiatry as a career choice has been reported [29].India with its developing background is no immune to it where the problem is magnified by the fact that less scientific, more religious, magical, and supernatural etiological and treatment approaches for mental illness exist in the society, particularly conspicuous in rural areas. With limited availability of mental health workforce (0.07 psychiatrists/100,000 population and 0.12 psychiatric nurses/100,000 population) [30], India is facing an acute shortage of professionals with either zero or insufficient training, supervision, and support to recognize, refer, and follow-up those with mental illness [30].According to one of the studies, the teaching of psychiatry at the UG level was either disorganized or not done properly [18]. Other studies have reported that compared to other specialists, psychiatrists are perceived to earn less money, to be less respected, and to have less prestige [31-34], social stigma, disapproving attitude of non psychiatric faculty and assumed higher rate of psychiatric morbidity in psychiatrists are other factors enumerated. [35,36].The attitudes to psychiatry among medical undergraduates have been regarded as key factors in determining the choice of psychiatry as a career and willingness to deal with psychiatric disorders in general practice [37]. Most part of attitude building toward specialty subjects takes place during UG training. Therefore, attitude of medical students is of utmost importance. Thus, an understanding of the attitudes of medical students toward psychiatry is important, asthey are the potential trainees in psychiatry. The study was planned to know the perception, knowledge, and attitude toward psychiatry as a discipline and as a career option among undergraduates of different years of medical education.

2. Aims and Objectives

- The inability to attract medical graduates to specialize in psychiatry has always been a serious challenge to psychiatry training programs. Therefore, this study was undertaken to assess the attitude of second year medical students, toward psychiatry as a subject of speciality, patients with mental illness, treatment modalities offered in psychiatry, and their wishes to take up psychiatry as a career.

3. Materials and Methods

- A cross-sectional study was conducted among 110 second year medical students of Teerthanker Mahaveer university.The attitude of medical students towards psychiatry was measured by Attitude toward psychiatry -30 (ATP-30) [38]. Consent was taken individually from all the 2nd year medical students (total=140), out of which 30 students refused to give the consent. The questionnaire was explained in detail to the rest of the 110 students.The collected data was analyzed by SPSS version -20 using independent samples t-test plus bivariate and multivariate logistic regression.

4. Study Design and Sample

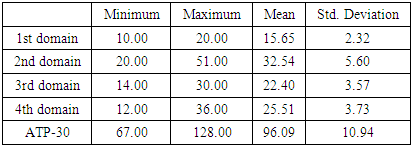

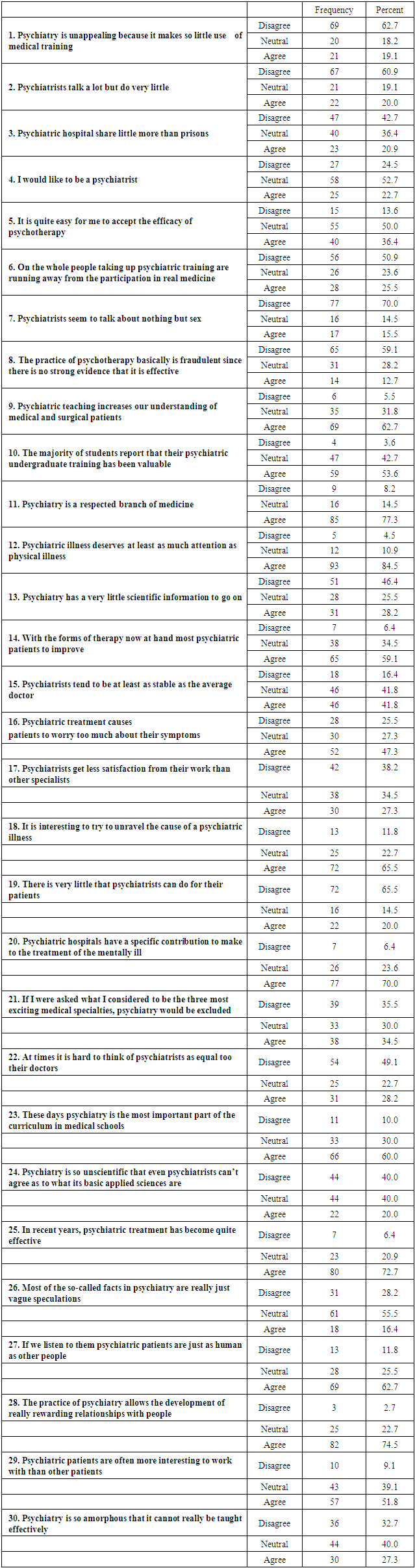

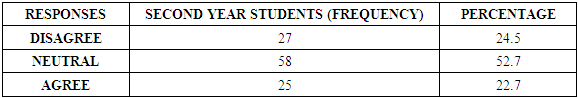

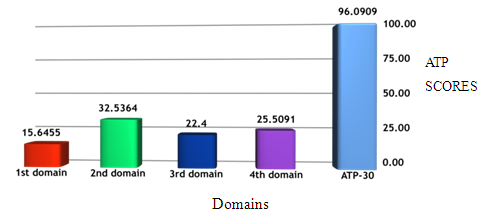

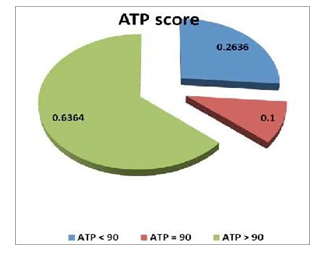

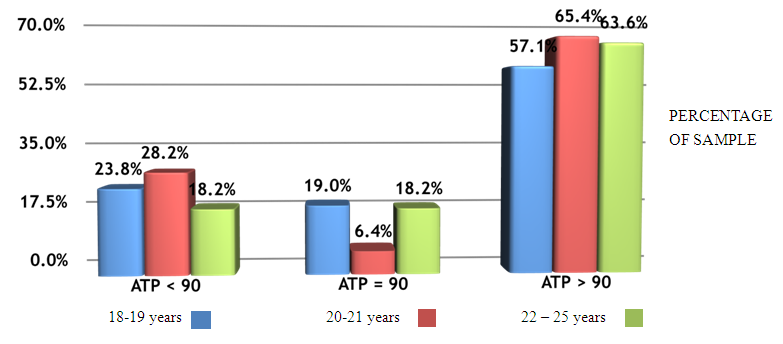

- This cross sectional study was conducted at a tertiary care teaching medical college of Moradabad. All of 150 second year students were approached to be part of the study. Anonymity was maintained and the students were explained about the objectives of the study,and were requested to fill the ATP-30 questionnaire after taking informed consent. Out of all the second year students approached 110 consented to take part and filled and returned complete questionnaires.The ATP-30 scale is a 5-point likert scale designed and validated by Burra et al. on a group of Canadian students38. This scale has been used in multiple surveys across different countries all over the world in English form and has proven validity. Thescale consists of 30 positively and negatively phrased items that measure the strength of respondent’s attitude to various aspects of psychiatry. A score of 1 denotes a highly positive attitude, 5 denote a highly negative attitude, and 3 denotes a neutral response. The score of each positively phrased item was converted by subtracting it from 6. The global scores range from 30 to 150. Global score of <90 (scores of 1 and 2 combined) suggests a negative attitude to psychiatry, a score of >90 (scores of 4 and 5 combined) denotes an overall positive attitude, while a global score of 90 (average score of 3) is considered to represent a neutral attitude. Each of the thirty questions were analyzed independently and thematically with group of questions together.The questionnaire was administered in English as the students were expected to be proficient in English as it was the language in which they were taught the curriculum.The components of the scale were grouped into four subgroups. (1) Psychiatric patients and psychiatric illness (2) psychiatrists and psychiatry career choice (3) psychiatric knowledge and teaching (4) psychiatric treatment and hospitals for analysis as done in previous studies [39,40].

5. Stastical Analysis

- Descriptive statistics was performed by calculating mean and standard deviation for the continuous variables. Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentage. Nominal categorical data between the groups were compared using chi-square goodness-to-fit test.The software used for the statistical analysis were SPSS (statistical package for social sciences) version 25.0 and MedCalc software.The statistical tests used were:❖ One-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) test for comparison of difference between mean values of more than 2 groups when the data follows normal distribution.❖ Post-hoc tests are run to confirm where the differences occurred between groups, or they are used for the inter-group comparisons. Post hoc tests attempt to control the experimentwise error rate (usually alpha = 0.05) in the same manner that the one-way ANOVA is used instead of multiple t-tests.❖ Unpaired or Independent t-test is used for comparison of mean value between 2 groups when the data follows normal distribution.❖ Chi-square test is used to investigate whether distributions of categorical variables differ from one another.❖ The p-value was taken significant when less than 0.05 (p<0.05) and Confidence interval of 95% was taken.

6. Results

|

| Figure 1. ATP scores of the 4 domains |

|

|

|

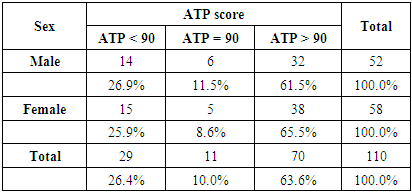

| Figure 2. ATP scores distribution across the sample |

|

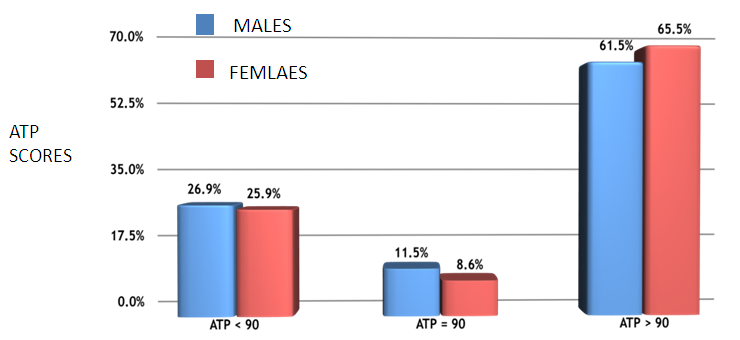

| Figure 3. Distribution Of Atp Scores According To Gender |

|

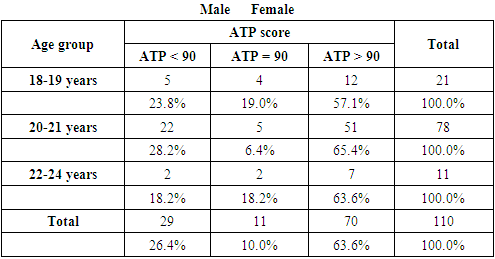

| Figure 4. Distribution of ATP Scores According to Age |

|

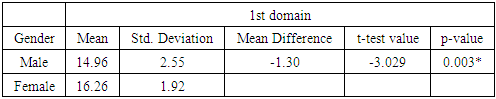

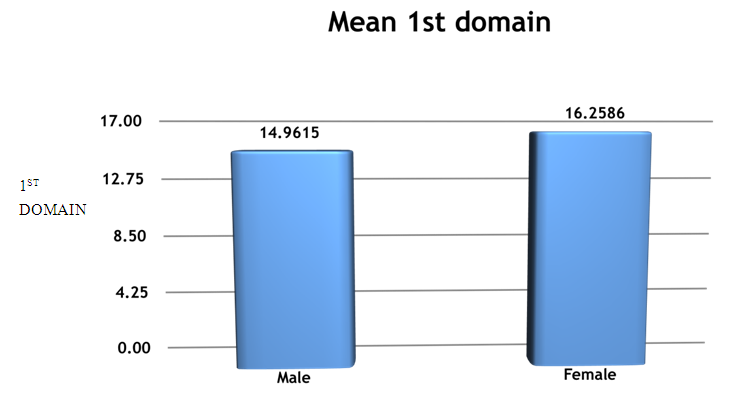

| Figure 5. Mean Distribution of 1st Domain Scores as Per Gender |

|

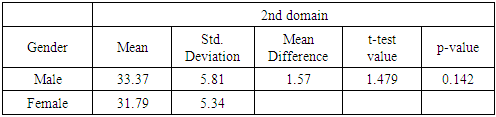

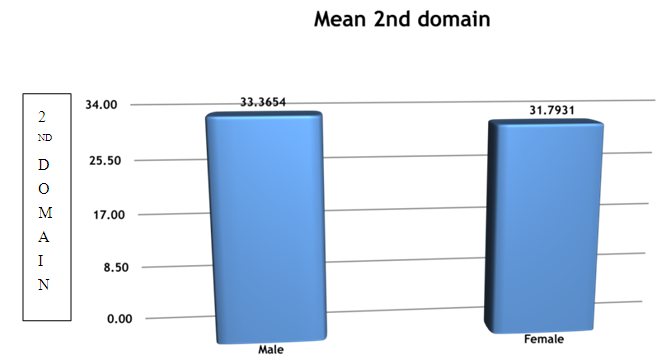

| Figure 6. Distribution of Second Domain Scores as Per Gender |

|

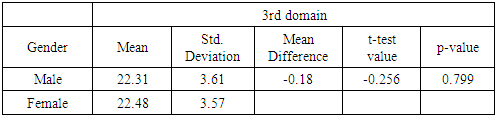

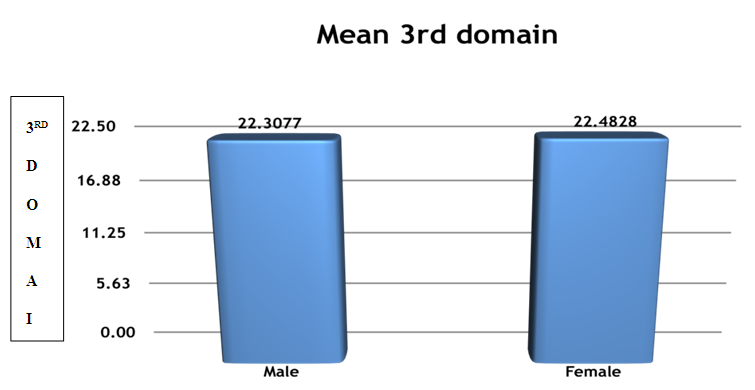

| Figure 7. Distribution of 3rd Domain Scores as Per Gender |

|

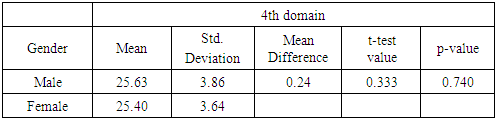

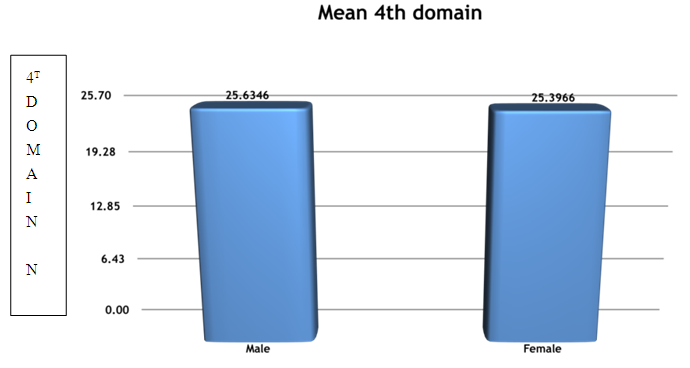

| Figure 8. Distribution of 4th Domain Scores as Per Gender |

|

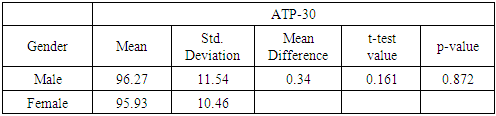

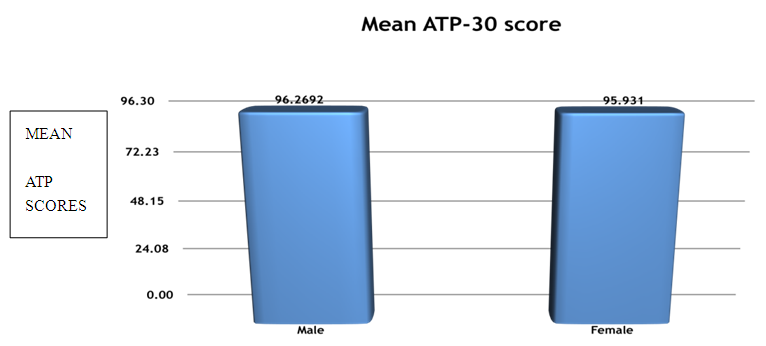

| Figure 9. Distribution of ATP Scores According to Gender |

|

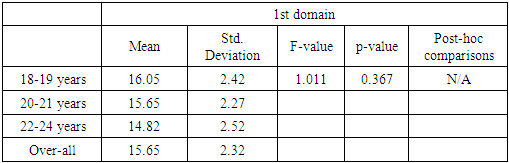

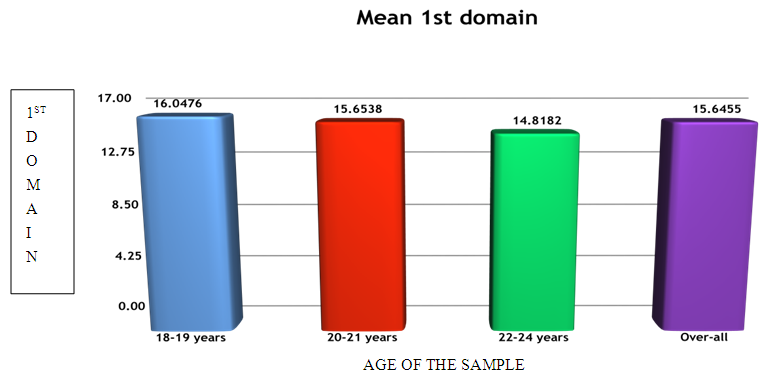

| Figure 10. Distribution of first domain scores as per age |

|

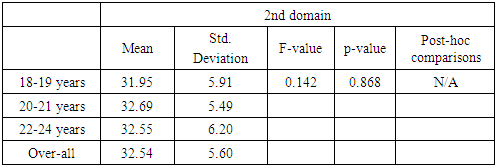

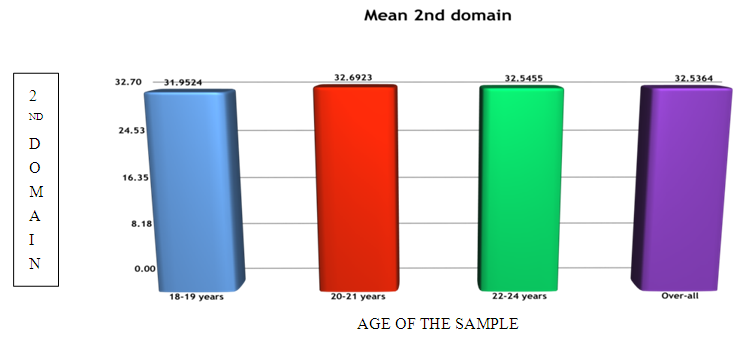

| Figure 11. Distribution of ATP scores on second domain as per age |

|

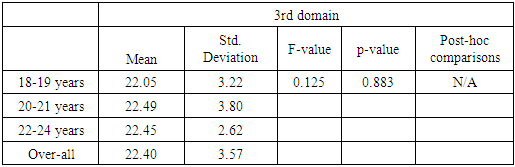

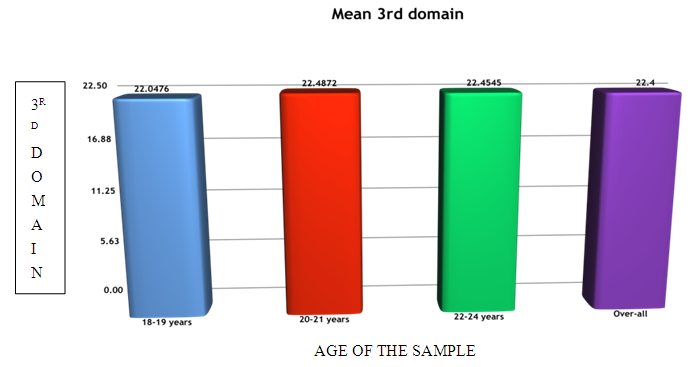

| Figure 12. Distribution of 3rd domain scores as per age |

|

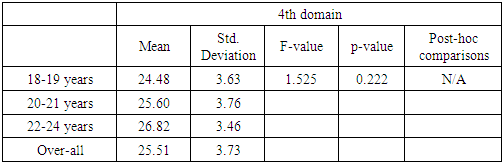

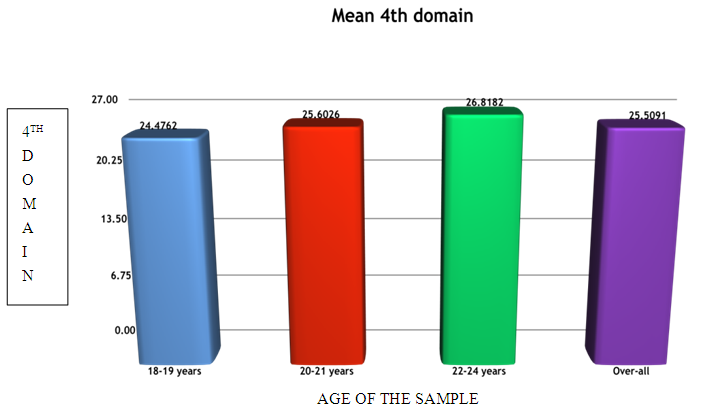

| Figure 13. Distribution of 4th domain ATP scores as per age |

7. Discussion

- The present study was designed to know the attitude of second-year medical students toward psychiatry as a specialty and career option. Nearly 63.6% of second year medical students had positive attitude toward psychiatry (chi-square value = 0.313, p=0.855).Only 22.7% second-year students affirmatively indicated to choose psychiatry as a career choice while 24.5% denied choosing psychiatry as a speciality and 52.7% had neutral attitude toward choosing psychiatry [table 2]. The students agree that psychiatry is a respected branch of medicine and that the practice of psychiatry allows the development of really rewarding relationships with people.We found that the students showed positive attitude toward psychiatric patients and psychiatric illness and they all agree that psychiatric patients are just as human as other people and they deserve atleast as much attention as physical illness. Moreover, the positive attitude was significantly more among females compared to males. [table 7]In the area of psychiatric knowledge and teaching, the students agree that psychiatry is the most important part of the curriculum in medical college, it helps them better understanding the medical and surgical patients and that their psychiatric undergraduate training has been valuable.Further in the area of psychiatric treatment and hospitals for analysis, the students showed positive attitude and agreed that psychiatric hospitals have a specific contribution to make to the treatment of the mentally ill, psychiatric treatment has become quite effective now and psychotherapy is effective. The students disagreed that the practice of psychotherapy is fraudulent.Despite all the stigma towards psychiatry our students had more positive attitude toward psychiatry. A good number of students gave “neutral” response to most of the items of ATP-30. This is expected to happen when the respondents have little knowledge about the topic of interest. This is likely the case with our students who have not been exposed to any psychiatric lecture and posting yet. It is likely that the students may be ambivalent to the various domains of the ATP-30.Like any other study, there are some limitations of this study including small sample size and it included medical students of single institution only. The study participants were aware of our area of interest, which could have influenced some of the responses.

8. Conclusions

- The study sheds light on the positive attitude towards Psychiatry by second year medical students. the domains for acceptance of psychiatric illness as a medical disorder and treating it likewise was found significantly more in the female students.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML