-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

p-ISSN: 2332-8355 e-ISSN: 2332-8371

2019; 7(1): 8-17

doi:10.5923/j.ijcp.20190701.02

Predicting Students’ Psychological Well-Being through Different Types of Loneliness

Mehrdad Shahidi1, 2, Frederick French3, Mahnaz Shojaee4, Gloria Bellido Zanin5

1Department of Psychology, Tehran Central Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

2Nova Scotia Inter-University Doctoral Program in Educational Studies, MSVU, Canada

3Department of Education, Mount Saint Vincent University, Canada

4Centre for Research in Applied Measurement and Evaluation, University of Alberta, Canada

5Mataró Hospital, Mental Health Service, Barcelona, Spain

Correspondence to: Mehrdad Shahidi, Department of Psychology, Tehran Central Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background/Objectives: Previous studies demonstrated that loneliness can predict psychological well-being (PWB). Nevertheless, loneliness in different areas of relationships (e.g., family, romantic/sexual, friendship, and group relationships) may affect PWB differently. Method: One hundred and eighty-two university students aged between 19 and 30 years old participated in this study. Ryff’s 42-item PWB Scale, Differential Loneliness Scale - Student Version, and a Demographic Questionnaire were used. To differentiate the levels of PWB in terms of four types of loneliness, the means analysis was used. Also, the power of four types of loneliness in predicting the components of PWB was examined by the multiple linear regression - stepwise procedure. Results: The findings revealed that loneliness in romantic/sexual and friendship relationships can significantly predict all components of PWB in students. Compared with the other types of loneliness, students suffered more from loneliness in romantic/sexual and friendship relationships. Also, students who were living with their partners and had one sibling suffered less from loneliness in the area of romantic/sextual relationship. Conclusion/Implication: The study indicated that loneliness in romantic/sexual and friendship relationships could affect different aspects of PWB negatively. Therefore, mental health professionals can lead their intervention programs toward the romantic/sexual and friendship relationships to enhance students’ psychological well-being.

Keywords: Loneliness, Psychological Well-being, Romantic Relationship, Friendship Relationship

Cite this paper: Mehrdad Shahidi, Frederick French, Mahnaz Shojaee, Gloria Bellido Zanin, Predicting Students’ Psychological Well-Being through Different Types of Loneliness, International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2019, pp. 8-17. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcp.20190701.02.

1. Introduction

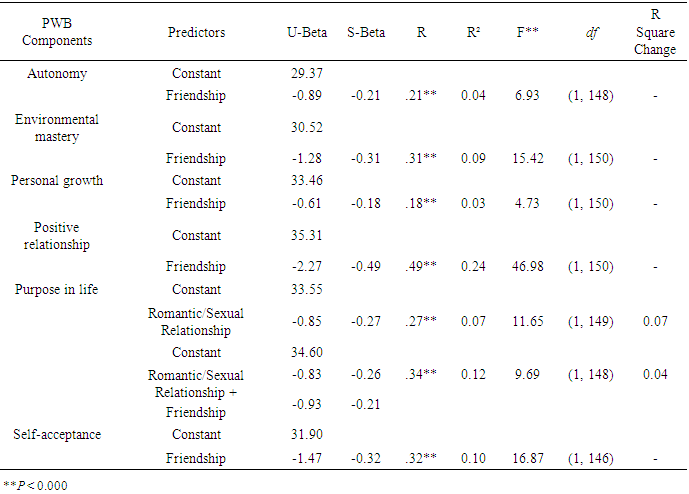

- Psychological well-being (PWB) reflects a worldwide utopia about what is ‘good’ for an individual. To inform and to make this utopia attainable, Ryff’s theory of psychological well-being has emerged and developed through four conceptual, instrumental, causal, and interventional orientations historically. Although these trends have progressed parallel to each other, they can be explained separately. The conceptual orientation was focused on understanding, justifying, and theorizing the meaning and the characteristics of psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989; Ryff, 2013; Ryff, 2017). Following this trend, Ryff has scrutinized the features of psychological well-being in various perspectives and theories. Being influenced by the perspective of ancient Greek philosophers (e.g., Aristotle's) about happiness, eudaimonia, hedonia, and satisfaction, Ryff introduced six major aspects of PWB from nine fundamental psychological theories (Figure 1) (Crisp, 2008; Raibley, 2010; Beecher, 2009; Bloodworth; 2005; Ryff, 1989; Ryff, 2013; Ryff, 2014; Ryff, 2017). These components are purpose in life, personal growth, self-acceptance, positive relations with others, environmental mastery, and autonomy (Ryff, 1989, Ryff, 2013, Ryff, 2014, Ryff, 2017).

| Figure 1. Core Dimensions of Psychological Well-being and their Theoretical Foundations (Adapted from Ryff, 2014, p. 11) |

2. Method

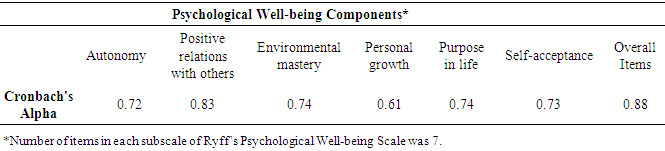

- Sample One hundred and eighty-five students who enrolled in psychology and sociology programs at Islamic Azad University-Tehran Central Branch (IAU-TCB) participated in this study. All participants were selected randomly and were informed about the ethics and confidentiality in this research before receiving the questionnaires. After collecting and exploring data, three responses were excluded from the study. Of 182 remained participants, 32% were aged between 19 and 21 years old, 40% were between 22 and 26, and 28% were between 26 and 30 years old. Similar to the characteristics of the student population, 78% of participants were female and 22% male. The proportional discrepancy between female and male students in Iranian universities is mostly based on women’s cultural preferences and universities’ admission policy by which female students are remarkably more than male students (Rezai-Rashti, 2012; World Bank Middle East and North Africa Social and Economic Development Group, 2009). More than half of participants were single (70%), and 15% were married and the rest did not specify their marriage status.InstrumentsPWB Scale: Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale was used to measure six components of PWB including self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life and personal growth (Ryff, 1989, 2013, 2017; Van Dierendonck, 2005; Cheng, & Chan, 2005; McDowell, 2010). This scale is constructed based on clinical and life span developmental theories related to mental health (Van Dierendonck, 2005). From different versions, the 42-item scale was used in this study. The scale had reasonable validity and reliability examined by several researchers in different societies (Van Dierendonck, 2005; Ryff, 1989; Ryff, & Singer, 2008; McDowell, 2010; Shahidi, 2013). In the target population (IAU-TCB), two primary psychometric studies were done on the 42-item version of Ryff’s PWB scale demonstrating Cronbach’s Alpha 0.88 (Fattahi, 2016) and 0.87 (Rezaghan, 2018). As Table 1 displays, in the current study, the internal consistency for each subscale and the total items of the scale is acceptable.

|

|

3. Results

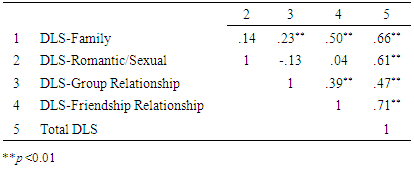

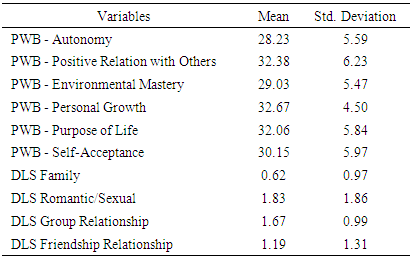

- The results of descriptive indexes are shown in Table 3. Descriptive indexes were explored to find missing data and were checked for the assumption of normality. Exploring variables showed that a few of responses in all major scales were missing. That is, the respondents did not answer from 2% to 8% of questions in a few subscales. Since the missing data was less and because the number of samples for each independent variable is more than 1/15 for statistical analysis (e.g., T-test, MANOVA, and linear regression- Beshlideh, 2012), the different valid N did not violate fundamental assumptions of used statistical methods and then the missing data were not replaced with means. However, the valid N was different in each variable resulted different df in statistical procedures.

|

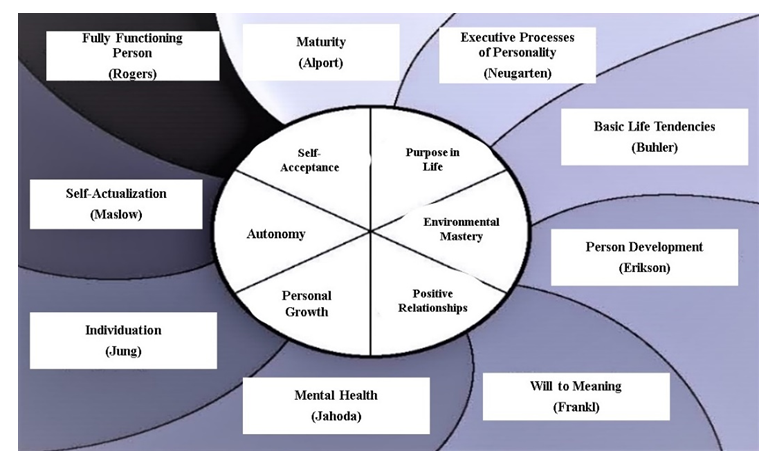

| Figure 2. Students’ Mean Scores in Four Types of Loneliness |

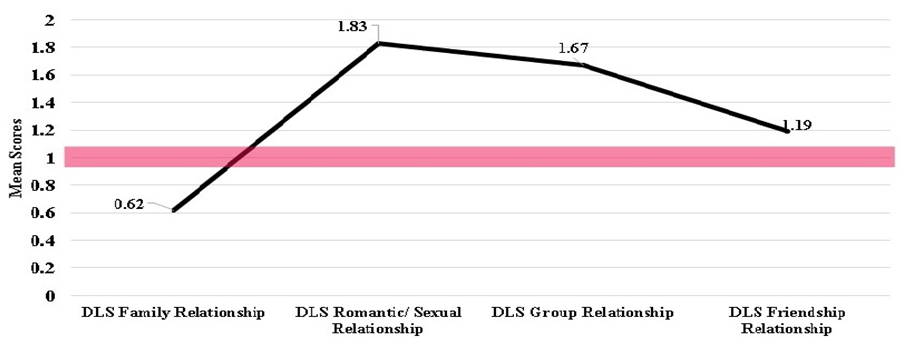

| Figure 3. Students’ Mean Scores in PWB Components |

|

|

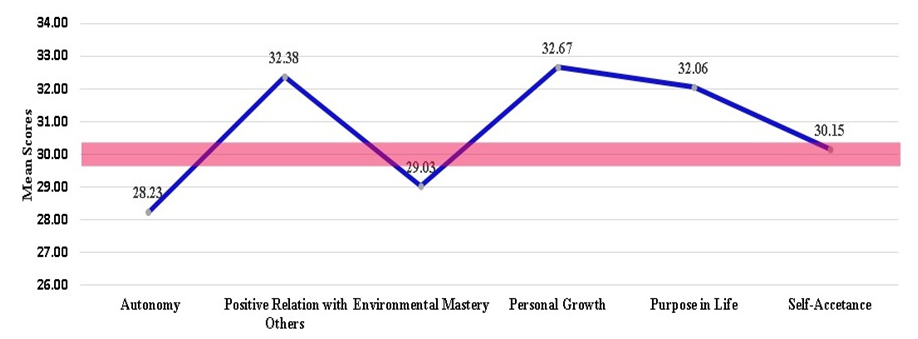

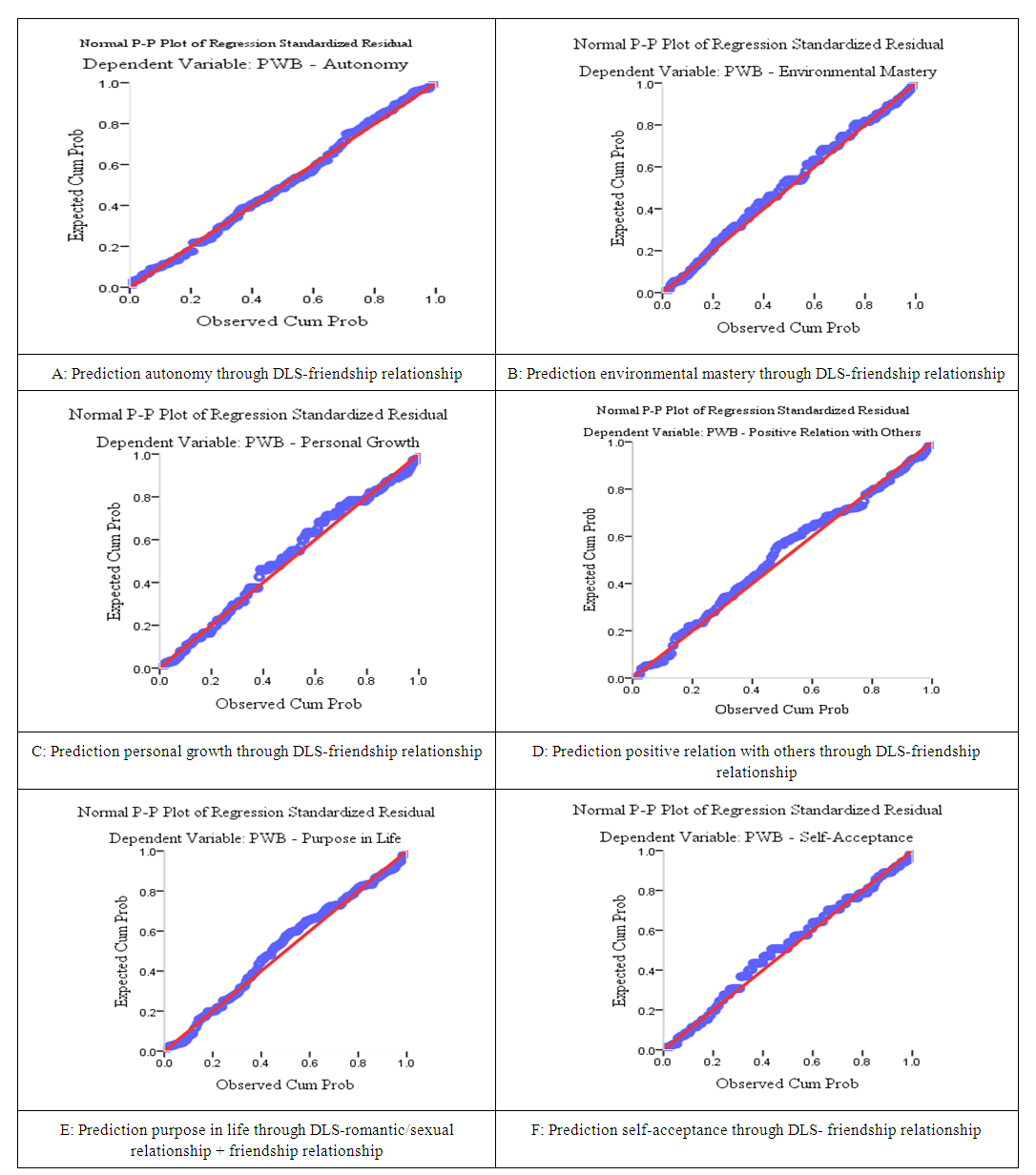

| Figure 4. Scatterplots of Regression in Predicting PWB Components through Four Types of Loneliness |

4. Discussion and Implication

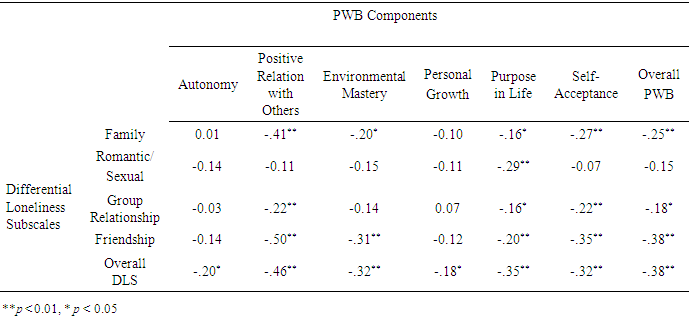

- Adequate functioning in PWB components can strengthen positive mental health for young adults. However, there are many factors that may limit the chance of achieving PWB. These factors sometimes increase the risk of mental health problems in adolescents and young adults (Santrock et al., 2005; Michaud & Fombonne, 2005). Unfortunately, these influential factors, which differ in type, effect size, and predictive value, were less studied. Among these factors, the impact of loneliness on PWB was studied based on the theory of unidimentionality (Shahidi, 2013). However, there is another view in which loneliness often occurs in the different types and levels of relationships (Firmin et al., 2014; Russell, Cutrona, Mcrae, & Gomez 2012). Accordingly, loneliness in such relationships may have different impacts on individuals' PWB. To examine this hypothesis, the level of loneliness and PWB in students, the association between four types of loneliness with PWB components, the predictive role of four types of loneliness in PWB, and the role of some demographic variables in four types of loneliness were analyzed. As the results of this study showed, students at the age between19 and 26 years old were more suffering from loneliness in romantic/sexual relationships compared with the other types of their relationships (Figure 1). Using cut-score based on students’ mean scores in PWB, the results revealed that their autonomy and environmental mastery are lower than baseline compared with the other PWB components. The association between PWB components and loneliness in four types of relationship revealed that the increase of loneliness in three types of relationships including family, group, and friendship is negatively associated with all PWB components. This aligns with previous studies in which loneliness was associated with PWB negatively (Shahidi, 2013). However, loneliness in romantic/sexual relationship was only associated with the component of purpose in life in Ryff’s PWB scale negatively. This finding supported the previous research in developmental psychology that indicated adolescents and young adults are more seeking romantic relationship as a major purpose in their lives (Santrock et al., 2005; Demetriou, Doise, & Van Lieshout, 1998), and romantic frustration makes them more vulnerable to loneliness (Seepersad, Choi, & Shin, 2008). In addition to significant effect size in predicting the component of purpose in life (Table 5), loneliness in the areas of friendship and romantic/sexual relationships could predict the other components of PWB. One of the justifications of this result refers to emotional development during 19-26 years of age. Since adolescents’ and young adults’ relationships are romantic, sexual, and friendship-oriented developmentally (Santrock et al., 2005; Håkansson, 2010; Gillibrand, Lam, & O’Donnell, 2011), and because they are vulnerable to negative changes in such relationships (Pedersen & Pithey, 2018; Seepersad et al., 2008), it can be concluded that loneliness in the area of romantic/sexual relationships is more effective in reducing their psychological well-being, particularly their purpose in life.In relation to demographic factors, the results showed that students who live with their partners and have one sibling were less suffering from loneliness in the area of romantic/sextual relationship. This finding supports Stronge, Overall, and Sibley’s (2019) research that indicated having romantic partner increases subjective well-being. There are some implications of such results. Mental health professionals should direct their interventional programs toward two major factors, romantic/sexual relationship and friendship relationship, for individuals whose age is in the range of 19 to 26 years old and suffer from loneliness. Particularly, when they use interventional programs for enhancing PWB in adolescents it may be necessary to assess adolescents’ and young adults’ levels of loneliness. Also. these findings should direct the attention of families, educational policy makers, and universities governors toward the effect of friendship relationship in enhancing adolescents’ self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life and personal growth.

5. Conclusions

- Generally, the current research indicated that the sense of loneliness in university students, which mostly was attributed to romantic relationships, was higher than other types of loneliness. Also, this type of loneliness, which may happen due to the lack of or failure in romantic relationships, was negatively associated with PWB-purpose in life. Having significant effect size in predicting the components of PWB, students’ loneliness in friendship relationship and romantic relationship were interpreted through the hedonic and eudaimonic approaches of well-being that was postulated in Ryff’s perspective of well-being. However, the lack of gender comparison and the lack of large sample size were major limitations the research faced. Accordingly, to interpret and generalize the findings of the current research, these limitations along with the cultural context of university students should be considered. The future studies may be directed toward the gender comparison and cultural differences in PWB and four types of loneliness through using large sample size.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML