-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

p-ISSN: 2332-8355 e-ISSN: 2332-8371

2017; 5(2): 39-49

doi:10.5923/j.ijcp.20170502.03

Effect of Delayed Consultation Liaison Psychiatry Service to the Improvement of Functional Disability and Psychiatric Symptom and to the Length of Hospital Stay

Ireine Suantika Cornelia Roosdy, Sonny Teddy Lisal, Muhammad Faisal Idrus, Saidah Syamsuddin, Andi Jayalangkara Tanra

Department of Psychiatry, Medical Faculty, University of Hasanuddin, Makassar, Indonesia

Correspondence to: Ireine Suantika Cornelia Roosdy, Department of Psychiatry, Medical Faculty, University of Hasanuddin, Makassar, Indonesia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

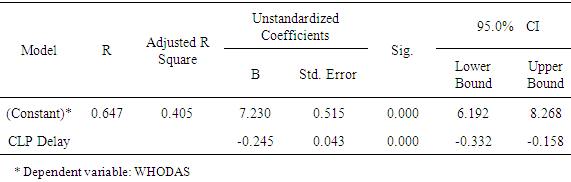

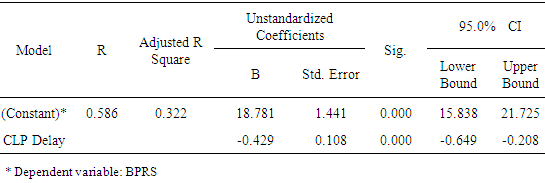

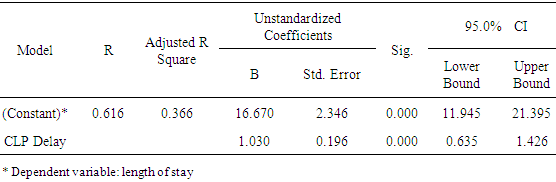

Observing morbidity in its time-related progression is important to prevent worsening of a disease or disorder. Nevertheless such prevention on psychiatric disorders is complicated due to its multifactorial etiology, but still can be prevented in the course of the disease by early detection and intervention. A significant association between general medical conditions and comorbidities of psychiatric disorders has long been recognized. But most psychiatric disorders are less recognizable and underdiagnosed by non-psychiatric physicians, leading to the possibility of many cases of psychiatric disorder comorbidities failed to be diagnosed at the early stage, which leads to deterioration and prolonged length of hospital stay. This study was conducted in prospectively cohort fashion on 47 inpatients with general medical problems consulted to Psychiatric Unit of Wahidin Sudirohusodo Hospital and treated with consultation liaison psychiatry (CLP) service. The purpose of this study is to find out the correlation between delayed CLP service initiation and the improvement of functional disability, psychiatric symptoms, and length of hospital stay. This study found that the longer the delay for initiating CLP service, the less improvements in functional disabilities and psychiatric symptoms achieved, and the longer is the length of hospital stay. Regression analysis indicates a potential decrease of WHODAS score of 6.985 points and decrease of BPRS score of 18.352 points per day delay of CLP service initiation. Delaying CLP service initiation for one day also potentially adds 17.7 days of hospital day care. Nevertheless, with sufficient correlation strength (r = 0.425) and predictive value 0.366, the assumption of the prolonged on length of hospital stay is still strongly influenced by other contributing factors up to 63.4% apart from time delay of CLP service.

Keywords: Time delay, Consultation liaison psychiatry, Functional disability, Length of stay, Psychiatric disorders comorbidity

Cite this paper: Ireine Suantika Cornelia Roosdy, Sonny Teddy Lisal, Muhammad Faisal Idrus, Saidah Syamsuddin, Andi Jayalangkara Tanra, Effect of Delayed Consultation Liaison Psychiatry Service to the Improvement of Functional Disability and Psychiatric Symptom and to the Length of Hospital Stay, International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2017, pp. 39-49. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcp.20170502.03.

1. Introduction

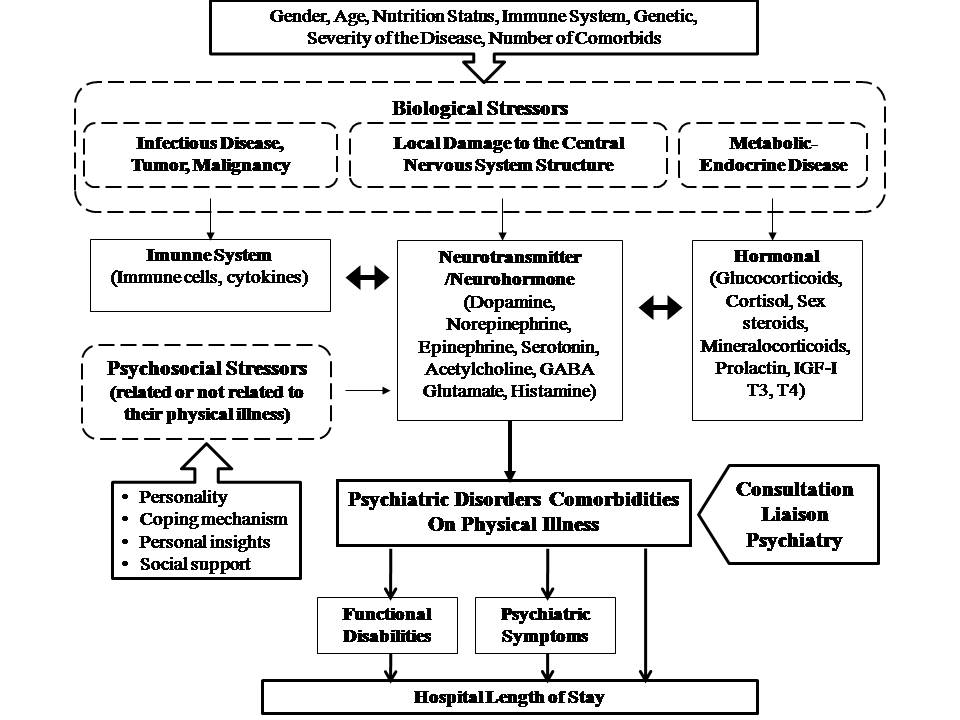

- Analysis of time factor and its effect on the incidence and progression of a disease or disorder is very important in epidemiological investigations. Viewed on the basis of time spectrum of illness or disease, i.e. the sequence of events presented from the exposure to etiologic agents to the occurrence of disability or death, only small portion were immediately recognized by physician at the time it fully developed. The incubation period of a disease and the early stages of the disorder are as important as the full manifestation of the disease itself. Studying time-based morbidity is important to prevent disease progression or disruption to deterioration [1].Traditionally disease prevention is divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. Primary prevention seeks to prevent the occurrence of a disease in the population by taking action to propagate health information and increase awareness of healthy lifestyles. Secondary prevention attempts to reduce the rate of disease or its incidence within the population through early detection and immediate intervention of the diagnosed disease. Tertiary prevention aims to inhibit the progression of the disease to avoid disability [2].The prevention of psychiatric disorders has not been well defined as the prevention of infectious diseases, screening for psychiatric disorders has no clear limits as screening for breast or colon cancer. Prevention of psychiatric disorders is made more complex by the nature of its multifactorial etiology, such as life stressors, genetic factors, and neurochemical changes in the body. However difficult it is to control all of these factors in order to prevent psychiatric disorders, the progress can be interupted by early identification and intervention. Early detection and intervention can shorten the duration of psychiatric disorders as soon as symptoms were detected. Early treatment can also prevent complications and deterioration, i.e. severe disability, increased recurrence of episodic disorders such as bipolar disorder, death due to suicide, and overutilization of health resources [3, 4].Mrazek and Haggerty (1994) propose a different preventive approach to psychiatric disorders, i.e. universal prevention, selective prevention, and indicated prevention.Universal prevention is defined as an intervention targeted at general population or to an entire population group that has not been identified sick but have an increased risk. Selective prevention targets individuals or subgroups of populations with significantly higher risk of mental disorders than average, as given evidence by biological, psychological or social risk factors. Indicated prevention targets high-risk individuals who are identified as having minimal signs or symptoms of mental illness but who do not meet the diagnostic criteria for the disorder at that time [5].A report written by the World Health Organization states that the prevention of psychiatric disorders is directed at determinants of various causal influence, which predisposes to the occurrence of disorders. In various studies it is known that there is a connection between physical and mental health, for example, cardiovascular disease can cause depression and vice versa. The presence of risk factor is associated with increased onset probability, greater severity, and longer duration of health problems [2].It had long been recognized that there was a significant association between general medical conditions and comorbidities of psychiatric disorders [6]. Saravay and Iavin conducted a meta-analysis of the effects of psychiatric comorbidities in 26 studies conducted on inpatients in the United States and several other countries, and found a significant association between comorbidities of psychiatric disorders and prolonged length of hospital stay. [7]One of the factors affecting treatment outcomes of inpatients is the case complexity. Kathol et al (2009) put forward the term "medical complex patient", to describe patients with large amount of medical resources use and has various complications of physical, mental, social and health problems, and has a higher mortality rate than patients without comorbid [8]. De Jonge et al (2006) previously called this concept the term "complex case" to describe a condition of multiple diagnoses of comorbid and interacting diseases that complicate one another, and in its management requires the involvement of various systems and expertise through effective interdisciplinary communication [9].

2. Methods

- This study is a longitudinal analytic study with a prospective cohort approach. Data were taken from the patient and his family as a direct source and from the patient's medical records as an indirect source. The study was conducted in Wahidin Sudirohusodo Hospital in Makassar within 6 months of observation from November 2016 to April 2017. The population of this study were all patients with general medical disorder who were hospitalized in Wahidin Sudirohusodo Hospital in Makassar and experienced symptoms of psychiatric disorders that were consulted to Psychiatric Unit of Wahidin Sudirohusodo Hospital for evaluation, management, and treated with consultation liaison psychiatry (CLP) approach during hospitalization. Samples were taken by consecutive sampling method that met inclusion and exclusion criteria.The inclusion criteria of this study were 17-70 years old at CLP initial assessment, diagnosed with mental disorders with International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10 diagnostic criteria, and were willing to contribute to the study. Patients were excluded if they meet any of the following criterias: (1) jointly administered by more than 3 other specialistic services for the diagnosis of different general medical illness; (2) the patient and / or his family were unable to provide sufficient information to complete WHODAS and BPRS scoring, and (3) to be in a life-threatening critical condition. The dropout criteria of this study were (1) the patient or the patient's family refused to continue the psychiatric management; (2) the patient has worsening, or suffered additional complications of other illnesses, or died as a result of the clinical course of the general medical disorder he suffered; and (3) the patient is discharged by the physician in charge or by his / her own request before reaching 7 days of CLP treatment.All patients eligible for inclusion in the study were assessed for functional disability using the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS version 2.0) instrument and the severity of psychiatric disorder symptoms was measured using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) instrument, both before CLP management began (DAS1 and initial BPRS [iBPRS]) and on the seventh day of CLP treatment (DAS7 and on treatment BPRS [tBPRS]). Data of initiation of CLP service delay (in days) and length of stay (in days) were also taken. CLP service delay were the number of days counted in two ways: (1) if the onset of psychiatric symptoms were before admission, the CLP delay were the number of days counted from the admission date until the date the Psychiatric Unit was consulted for the patients; or (2) if the onset of psychiatric complaints were during hospital stay for any physical illness, the number of CLP service initiation delay days were counted from the date when the psychiatric symptoms occured until the date of consultation request sent to Psychiatric Unit to initiate the CLP service. The data collected was processed and analyzed with SPSS© version 17.

3. Results

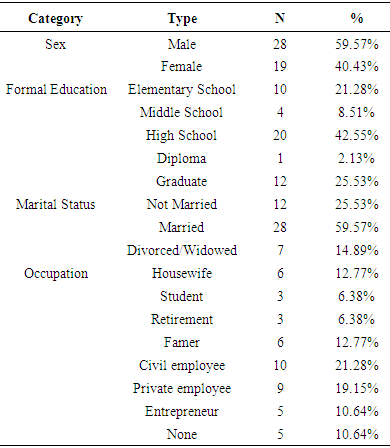

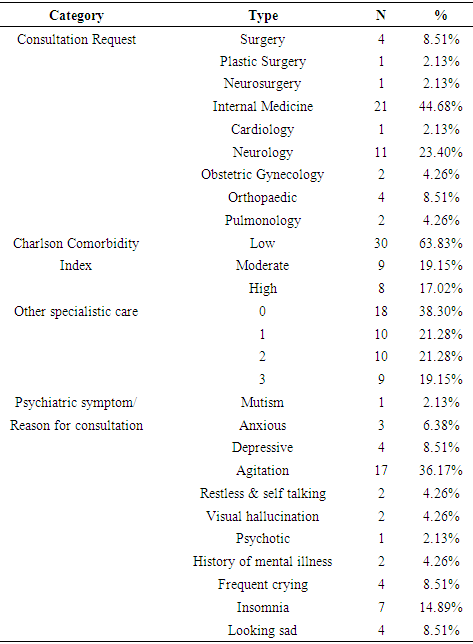

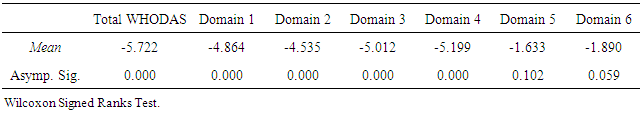

- A total of 87 in-patient consultation requests were recorded into Psychiatry Unit of RS Wahidin Sudirohusodo throughout the period of this study, and were given services with the approach of consultation liaison psychiatry. Subjects matching inclusion criteria were recruited consecutively and those who met exclusion criteria were excluded from the research data. Fifty six patients who met inclusion criterias were assessed using WHODAS 2.0 instrument (DAS1) for their degree of functional disabilities at the initial interview, and the severity level of psychiatric symptoms were assessed with BPRS (iBPRS).All subjects were treated in accordance with the standard procedure of consultation liaison psychiatry (CLP) service. In the observation period, nine subjects dropped out of the study, six were discharged by the primary responsible physician before the seventh day of CLP treatment, two returned home at their own request, and one patient died during tratment due to physical illness. At the end of the study, there were only 47 subjects left for statistical analyses with an average age of 42.04 years (SD + 13.01163), ranged from 17 to 70 years old. The forty-seven inpatients included in this study received 7 days CLP services for the evaluation of psychiatric disorders and integrated management of major physical disease therapy and mental disorder management. On the seventh day of patient care with CLP approach, the patients’ functional disability score were re-assessed with WHODAS instrument to evaluate the improvements in patients (DAS7) and psychiatric symptoms re-assessed with BPRS (tBPRS). The overall sample consisted of 28 male subjects (59.57%) and 19 female subjects (40.43%), more than half were married (59.57%), and most patients had formal education level until senior high school (42.55%) (Table 1).

|

|

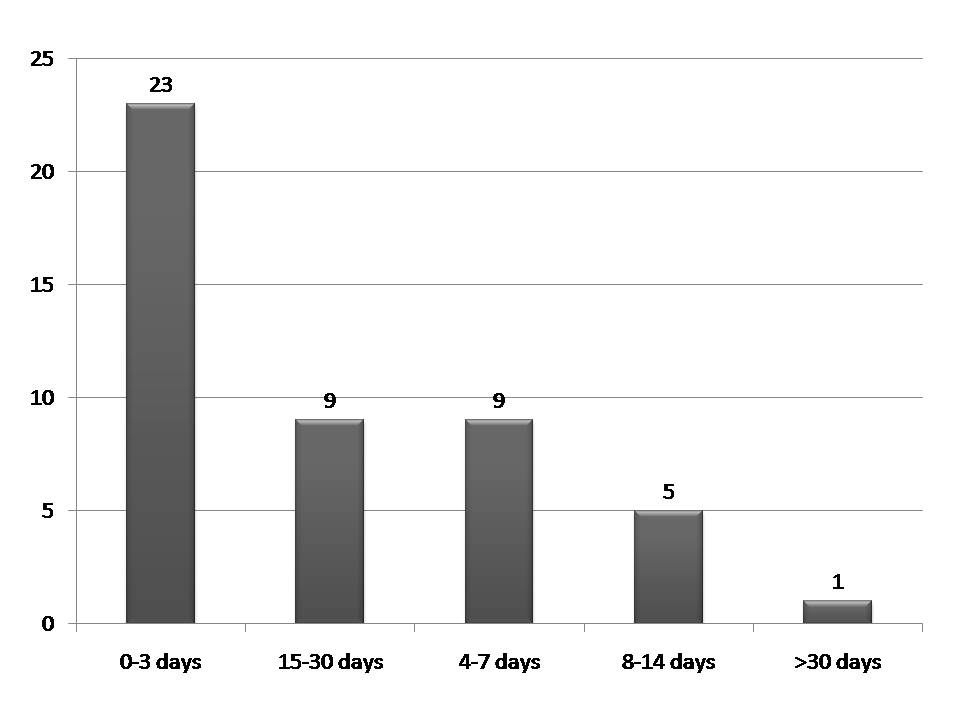

| Figure 2. Delay of CLP service initiation within the terminology of disease progression |

|

|

|

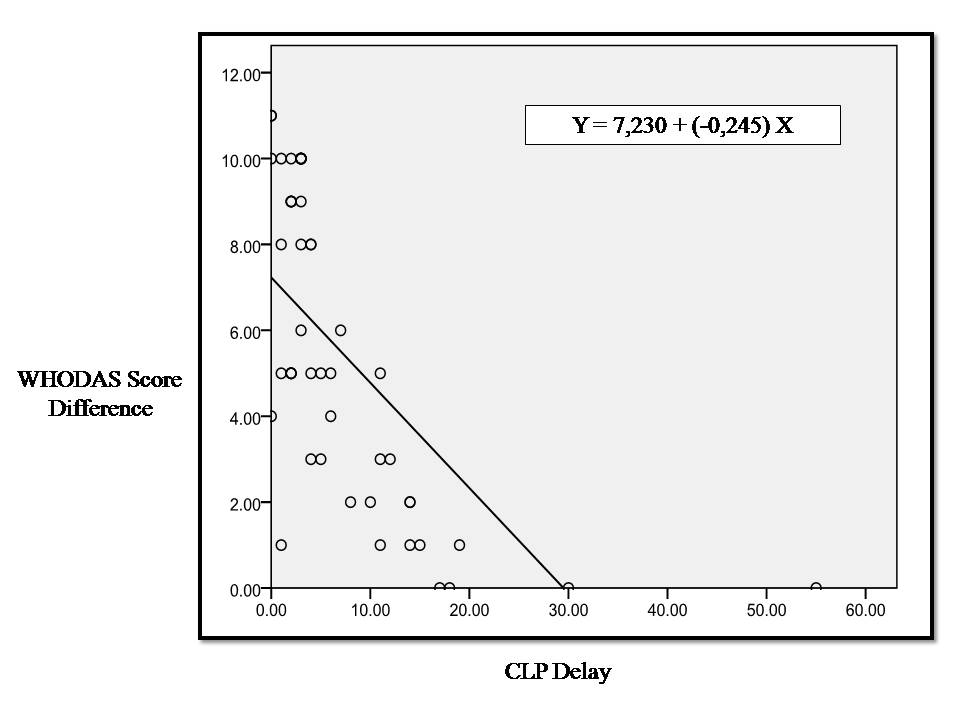

| Figure 3. Linear correlation between CLP initiation delay and improvement of functional disability represented by WHODAS score difference |

|

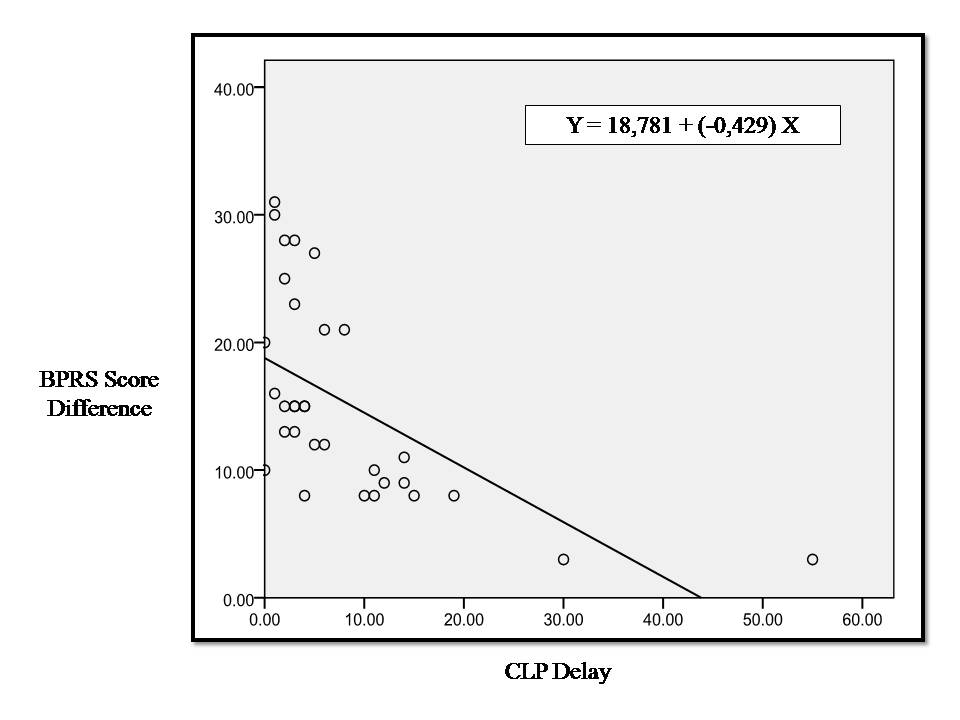

| Figure 4. Linear correlation between CLP delay and improvement of psychiatric symptoms represented by BPRS score |

|

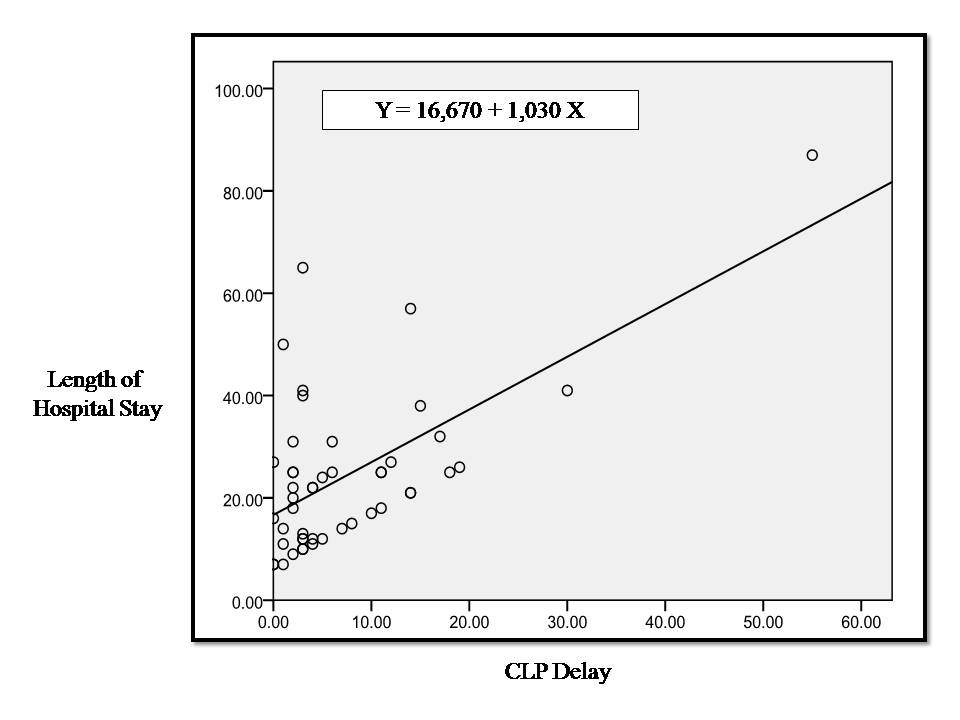

| Figure 5. Linear correlation between CLP initiation delay and the length of hospital stay |

4. Discussion

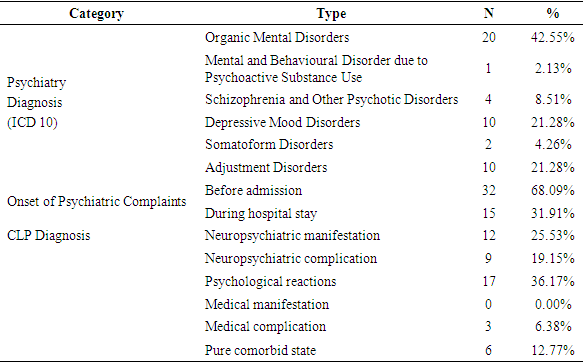

- Comorbidity of mental and physical disorders is a major challenge of medical treatment in the 21st century. This problem is often overlooked or even ignored by public health care providers as well as educators in the medical field, but actually has severe consequences, including worsening of the prognosis of physical illness and increased likelihood of complications and other related conditions, increased maintenance costs, and prolonged or permanent functional impairments [12, 19].We found in this study 86 consultation requests from various specialities of suspected psychiatry comorbid cases during the 6 months of study. This number is apparently still far from the expected number of cases of psychiatric disorders comorbidities on general medical illness in general hospital settings. The collaborative study conducted by the European Consultation-Liaison Workgroup as reported by Huyse et al [20] on CLP services in 56 healthcare providers from 11 European countries within 1 year, found an average of consultation request of only 1% of the total potential cases. This means that there is still a wide gap between the epidemiology and the services provided. The reluctance of non psychiatric physicians in charge to request for psychiatric assessment for their patients may be caused by various considerations. In this study we didn’t explore the reasons of other non psychiatric physicians for postponing consultations to Psychiatric Unit, nor exploring the difficulties or hindrance in being aware of any psychiatric problems early in the process of patient’s care.Goldberg concluded five reasons for inability to provide early detection of psychiatric disorders in general hospital settings. First, most patients like this do not show symptoms that indicate a psychological problem, but may express complaints of psychiatric disorder if asked directly. Secondly, patients have often mentioned some symptoms of depression or anxiety in the initial history taking along with their somatic complaints, but usually only the somatic complaints received more attention and were discussed further. Thirdly, clinical interviews or anamnesis are often conducted in conditions or places with less privacy so that most patients may deny the psychological problems when being interviewed in the open wards. Fourthly, the organic cause of all the symptoms complained by patients does not exclude the comorbidity of psychiatric disorders because in some cases it might be responsible for exacerbating the patient's complaint. Lastly, eventhough the doctor in charge had suspected a psychiatric disorder, most doctors were not confident in their ability to detect and assess symptoms of psychiatric disorders resulting in delayed referral [21].Booth et al study excluded female patients on the basis of previous studies that had shown female patients having various prevalence of psychiatric disorders compared to male [22]. Sayers et al studied inpatients with heart failure and comorbidities of psychiatric disorders suggests that female patients are more likely to experience comorbid than male (p <0.001) [23]. Proportion of subjects in this study were 28 male (59.57%) to 19 female (40.43%). Unlike previous studies done on CLP, in this study we didn’t limit subjects to specific general medical condition or any specific diagnosis group but all patients consulted to Psychiatric Unit were included consecutively, respectivelly this study showed that prevalence of male patients with physical illness consulted to Psychiatric Unit in overall CLP cases were slightly higher than female patients.This study found that majority of consultation requests were due to symptoms of agitation, followed by symptoms of insomnia, which were consistent with the findings that most cases consulted to psychiatry were diagnosed as organic mental disorders. Usually organic cause of psychiatric symptoms were consulted to psychiatry for their agitative behavior and were contributed to treatment non compliance and self-harming risks [22]. Huyse et al studied that the most common psychiatric diagnosis was mood disorder and organic mental disorder, followed by somatoform disorder and dissociative disorders [20]. These findings were similar to the prevalence of symptoms and diagnosis in this study.Seltzer's study on early detection as well as pattern of comorbidity psychiatric disorders in general medical illness suggests that the majority of patients referred to psychiatry were under severe condition of psychiatric disorders probably due to undetectable psychiatric disorder on early admission [11]. In this study we found that majority of psychiatric symptoms in general medical cases had onset before hospital admission (N = 32, 68.09%), and should have been detected early and had CLP services initiate before symptoms worsen, functional ability declined, and prolonged days of hospital care.A comprehensive approach to each of the psychopathologic symptoms were of great importance in CLP service. CLP plays an important role in discovering and determining pathologic interaction between current general medical conditions and psychiatric disorders resulting in the emergence of symptoms of psychiatric disorders [17, 24, 25]. The CLP diagnosis became important besides the main medical illness and the comorbid psychiatric disorder diagnosis because knowing the interaction pattern between these two sides of diagnosis was crucial in planing CLP approach and management for each case. In this study we only found five types of CLP diagnosis, and no case of “medical manifestations of psychiatric disorders”. Most cases were “psychological reaction to physical illness”, which actually proven the main important role of CLP in treating these types of patients. Prognosis for impovements in cases of “psychological reaction to physical illness” is good and should be much better if CLP intervention delivered earlier.Delays in the role of CLP in patients’ management may lead to delayed recovery of general medical conditions. Booth et al study showed that comorbid psychiatric disorders associated with substantial and significant reductions (p <0.001) in all dimensions of life function, with the greatest decrease seen in physical and emotional role functions [22]. Anxiety disorders and mood disorders are associated with significantly reduced functional capacity. Genetic and biomolecular findings related to the pathophysiology of mental disorders further confirm the relationship between body and soul, between physical manifestations and psychological disorders [16, 26]. Respectively, this study confirms a significant improvement after initiation of CLP service in all functional domains possible in hospitalized patients.A prospective study conducted by Fulop et al as a preliminary study of the effect of comorbidity of psychiatric disorders to the length of day of care of elderly medical / surgical patients was performed by analyzing functional disability, severity of the disease (using the Diagnosis Related Group [DRG] calculation), tribe, sex, age, and type of health insurance [27]. Fulop et al found no association between the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders and the length of stay, but initial functional status and severity of the disease were significant in determining prediction on days of hospital care [27]. In this study we first analyze the effect of delayed CLP initiation to the severity of functional disability and symptoms of psychiatric condition, and we found a significantly strong correlation. We then analyze the time factor of CLP service initiation directly to the length of hospital stay and found only moderate correlation occur, yet still significant enough (p = 0.003). We further analyze the effect of improvement of functional status and psychiatric symptoms to hospital length of stay and found less significancy level for both (p = 0.029 and p = 0.026, respectively). These findings indicates that better patients outcomes can be achieved with early assessments and interventions of psychiatric care to minimize overutilization and greater burden of care, such observations were also seen in several other studies regarding timeliness of CLP services [28-32]. However we further proven the important contribution of other factors besides time factor to the elongation of hospitalization days, which in this study are the functional status and severity of psychiatric symptoms.Several other factors were thought to contribute to the improvement of functional status and psychiatric symptoms as well as the length of hospital stay, namely age, sex, education level, marital status, occupation, type of disease, number of diagnosis, comorbidity index, onset, diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, and CLP diagnosis [15-17]. The limitation of this study as it serve as preliminary study was it analyze all cases regardless of other contributing factors. The result of this study as it showed that there was a low- moderate predictive value of CLP delay for each variables measured indicates the vast contributing factors other than CLP initiation delay to the improvement of life function, psychiatric symptoms, and length of stay.The advantages of this study was to provide predictions of potential improvements in functional disabilities, psychiatric symptoms, and length of stay. The disadvantages of this study were the diversity of data and variables which might influence in the analysis of data covering all CLP hospitalized patients without grouping per diagnosis of physical illness or per particular specialization. A more directed analysis of one type of physical diagnosis by calculating the severity of the disease per type of diagnosis and with the management variables might further sharpen the results obtained in this study.

5. Conclusions

- This study found a significant correlation between delay of consultation liaison psychiatry (CLP) service with the improvement on functional disability and symptoms of psychiatric disorders as well as length of treatment days. We found that the longer the delay of CLP service initiation, the less improvement on functional disability and psychiatric symptoms achieved, and the longer was the hospitalization days. Regression analysis conducted on the data showed a decrease in functional disability potency of 6.985 and also potentially added days of hospital care as much as 17.7 days for every one day delay of CLP service initiation. Regression analysis also indicates a decrease in potential BPRS score of 18.352.The results of this study could be used as basis for consideration to increase the awareness of non-psychiatric physicians upon the presence of symptoms of psychiatric disorders comorbid to physical illness. It is necessary to improve the ability of non-psychiatric physicians for early detection of psychiatric disorder to prevent worsening of symptoms and elongation in days of hospital care. On the other hand, the ability of a CLP service provider physician needs to be maintained and enhanced, especially in terms of the accuracy of diagnosis and the skill of interspesialistic communication.As a results of this study we recommend for training and mini symposia on early detection of psychiatric disorders to non-psychiatric physicians in public hospitals, especially triage doctors at emergency departments as the front guard for hospital services. A simple history-taking for symptoms and past episodes of psychiatric disorders should be a screening routine in the admission of new patients, to minimize the potential use of resources which can burden the hospital from the early stages of admission.A retrospective study that compares the severity of symptoms of diagnosis of certain psychiatric disorders in patients with a general medical illness between a group of patients receiving and not receiving CLP services is needed to provide more insights upon the relationship between CLP services and the improvement of symptoms of psychiatric disorders in hospitalized patients in public hospitals. Research by screening method can be done subsequently to patients treated by the Internal Medicine Departement because it was obvious in this study that most request for psychiatric consultation came from Internal Medicine, to examine the relationship between CLP service initiation according to each characteristics of internal medicine diagnosis.Further research is also needed in the field of hospital administration to compare the cost of care of inpatients who are consulted to the Psychiatric Unit for CLP services and who do not receive CLP services but have extended length of stay, and by assessing recurrence or re-admission rates associated with improvement symptoms of psychiatric disorders, quality of life, and functional abilities of patients receiving CLP services.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors declare no potential conflict of interest in writing this original article. The authors would like to acknowledge the important support and contributions of Jumraini Tammasse, M.D. (Neurologist) and R. Satriono, M.D. (Pediatrician; Clinical Nutrician; Research Methodology).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML