-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

p-ISSN: 2332-8355 e-ISSN: 2332-8371

2017; 5(1): 1-9

doi:10.5923/j.ijcp.20170501.01

Influence of Coping Strategies and Perceived Social Support on Depression among Elderly People in Kajola Local Government Area of Oyo State, Nigeria

Okhakhume Aide Sylvester, Aroniyiaso Oladipupo Tosin

Department of Psychology, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Okhakhume Aide Sylvester, Department of Psychology, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Health related issues like Dysphoric mood or loss of interest or pleasure in life and in free time activities, poor appetite, insomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, feelings of excessive guilt, lack of concentration, inability to think, withdrawn, despondent, disturbed sleep and reduced appetite observed among elderly people attracted the attention of this study to examine the influence of coping strategies and perceived social support on depression among elderly people. This study adopted cross sectional research design to examine the influence of coping strategies and perceived social support on depression among elderly people who are 60 years and above in kajola local government area of Oyo state, Nigeria. Purposive sampling technique was used systematically to select 200 elderly people that participated in the study. The result of the finding revealed that elderly people with low perceived social support reported higher depression than their counterpart with high perceived social support at [t(198)=-12.41, p<.05] and it was also discovered that elderly people with low coping strategies reported higher depression than their counterpart with high coping strategies among elderly people at [t(198)=-12.41, p<.05]. More so, the result of the findings depicted that, there was significant joint influence of coping strategies and perceived social support on depression [F(2,197)=43.86; p<0.05; R2=0.29] and further analysis revealed that coping strategies and perceived social support made significant independent contribution to depression among elderly people in kajola local government area of Oyo state, Nigeria [β=-0.15; t = -2.40; p<0.05 & β=1.24; t = 9.31; p<0.05].This study concluded with discussion of findings and recommend that family, relative, neighbour and government should provide adequate support to the elderly people in order to reduce depressive symptoms and mortality rate among them.

Keywords: Coping strategies, Perceived social support, Depression, Elderly people

Cite this paper: Okhakhume Aide Sylvester, Aroniyiaso Oladipupo Tosin, Influence of Coping Strategies and Perceived Social Support on Depression among Elderly People in Kajola Local Government Area of Oyo State, Nigeria, International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-9. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcp.20170501.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Prevalence rates of major depression have steadily increased during the past 60 years (Dishman, Washburn, & Heath, 2004), and the World Health Organization has predicted that by the year 2020 depression will be second only to cardiovascular disease as the leading cause of disability and death worldwide (Murray & Lopez, 1996). For older adults, depression might thus be viewed as a severe threat. The U.S. Consensus Development Panel of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (2003) stated that although safe and efficacious treatments exist, depression in particular remain a significant health care issue for older adults. For example, depressive disorder has been found to be a strong risk factor for suicide in the elderly (Wærn et al., 2002). Moreover, natural occurrences and changes associated with the process of aging, such as bereavement, increased loneliness, increased general and physical disability (Bruce, 2001), and declines in cognitive functioning (Boone et al., 1994) are linked to an increased risk of depression. Although there are contradictions in the literature (Blazer, 2003), recent incidence studies in Sweden support the notion that both the prevalence and the incidence of depression increase with age (Pálsson, 2000). It was some illnesses that can influence every aspect of a person’s life, including appetite, sleep, levels of energy and fatigue, and interest in relationships, work, hobbies, and social activities. Of course, everyone feels blue or low sometimes, but a depressive illness is not just a passing blue mood. It involves serious symptoms that last for at least several weeks and make it hard to function normally. Studies has shown that emotional stress or loss of function can sometimes trigger depression, although it can also develop without a clear precipitant. Strength of character or previous accomplishments in life do not prevent depression. Depression is not a sign of weakness or a problem that can just be willed away. People who have a depressive disorder cannot just “snap out of it.” without proper treatment. Their depressive symptoms can last for months or even years and can worsen. Research suggests that depressive disorders are medical illnesses related to changes and imbalances in brain chemicals called neurotransmitters that help regulate mood and can be trigger by psychological influence. Depression is the most common diagnosis in older adults who commit suicide, so it is critical that depression be recognized and treated as soon as possible. Depression is a psychological disorder that affects millions of people worldwide (WHO, 2001). In addition to causing both emotional and physical distress, depression is also cited as one of the leading causes of disability (WHO, 2001). Depressive symptoms may include mood disturbances, anhedonia, changes in weight, appetite or sleep patterns, low energy, psychomotor disturbances, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, poor concentration and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide (NIMH, 2011). Symptoms of depression can range from mild to severe, have varying impacts on daily functioning and have different temporal characteristics. A depressive state can occur in reaction to an acute stressor, multiple stressors, or no apparent cause, producing a brief disturbance in mood, cognitions and behavior. However, a mood disturbance may be classified as a disorder if it remains unresolved over time and is coupled with multiple depressive symptoms. The etiology of depression is complex, varied and not yet fully understood. Biological and psychosocial factors are both implicated in the development of depression, yet these factors may vary between individuals and types of depression. Many theories of depression propose a diathesis-stress model, in which a stressor interacts with an individual's biological or cognitive vulnerability to produce a depressive reaction. The severity and temporal characteristics of the stressor(s), as well as the individual's biological and genetic makeup (Caspi et al., 2003), use of coping skills (Matheson & Anisman, 2003), cognitive style (Alloy et al., 2000; Scher, Ingram, & Segal, 2005), and degree of social support (George, Blazer, Hughes, & Fowler, 1989; Gladstone, Parker, Malhi, & Wilhelm, 2007), may contribute to the development of depression. Several psychosocial factors have been associated with a higher risk of depression, including gender, socioeconomic status, marital status, social support and age. Interpersonal theories of depression suggest that some individuals are more prone to create more stressors in their lives (Hermanns et al, 2006). This stress generation process is hypothesized to occur because individuals, due to stable characteristics (e.g., personality traits) or temporary state (e.g., dysphoria), interact socially with others in ways that increase the likelihood of their experiencing further negative life events.Theory of coping strategies by Duangdao & Roesch, (2008) postulated Coping strategy as an individual’s cognitive and/or behavioral attempts to tolerate and manage situations that are perceived as stressful. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) were the first researchers to extensively study coping strategies, define it as ‘constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person. From this definition, they derived two primary categories of coping: emotion-focused coping and problem-focused coping. These categories described ways that individuals attempt to either change their emotional response to a stressor or change the source of stress directly. Emotion-focused coping, or “regulating emotional responses to the problem,” involved the use of such coping strategies as: seeking emotional support, cognitive reappraisal, avoidance and minimization. Conversely, problem-focused coping, or “coping that is aimed at managing or altering the problem,” involves the use of coping strategies such as making a plan of action (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In addition to the problem-focused and emotion-focused coping dichotomy, other higher-order categories of coping were developed that examined the focus or orientation of the coping strategy (Duangdao & Roesch, 2008; Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood, 2003). For example: approach versus avoidance (Roth & Cohen, 1986), vigilance versus nonvigilance (Averill & Rosen, 1972); vigilance versus avoidance (Cohen & Lazarus, 1973); alloplastic versus autoplastic (Perrez & Reicherts, 1992); attention versus inattention (Kahneman, 1973); intrusion versus denial (Horowitz, 1976), and direct versus indirect (Barrett & Campos, 1991).There are many ways to categorize coping strategies. One of the most commonly used categories is active coping versus passive or avoidant coping (Carrico et al., 2006). Active coping efforts are aimed at facing a problem directly and determining possible viable solutions to reduce the effect of a given stressor. Meanwhile, passive or avoidant coping refers to behaviors that seek to escape the source of distress without confronting it (Folkman & Lazarus, 1984). Setting aside the nature of individual patients or specific external conditions, there have been consistent findings that the use of active coping strategies produce more favourable outcomes compared to passive coping strategies, such as less pain as well as depression, and better quality of life (e.g. Holmes & Stevenson, 1990). On the other hand, relying on passive or avoidant coping strategies is associated with increased depression and anxiety (e.g. Clement & Schonnesson, 1998). According to Lazarus and Folkman (1984), people usually resort to a combination of problem-focused and emotion-focused coping in stressful encounters. Problem-focused coping concentrates on dealing with the stressor itself, whereas emotion focused coping tries to deal with the emotional response to a stressor (Bouchard et al. 2004). There is, however, no clear consensus as to which coping styles are most effective in terms of resolving problems or preventing future difficulties (Folkman & Moskowitz 2004). Lazarus (1991) asserts a close connection between the choice of coping strategies and the emotional experience. He suggests that self-blaming and avoidant strategies, such as behavioural disengagement, are related to negative emotions, whereas more approach oriented coping strategies and seeking social support are associated with positive emotions. Research has also shown that emotion-oriented and avoidant coping may, in the long run, be less adaptive than problem-focused coping, although the impact of these coping styles appears to depend on the specific constraints imposed by the stressful situation (de Ridder & Schreurs 2001). Research has suggested that problem-focused coping (such as problem solving, planning and seeking social support) may be particularly important for adjusting positively to diabetes (Cox & Gonder-Frederick 1992). In contrast, as shown in an earlier study by Karlsen et al. (2004), emotion-focused styles, avoidant coping and self-blaming predict impaired well-being and increased emotional distress among elderly people. Social support refers to support received (e.g. informative, emotional, or instrumental) or the sources of the support (e.g. family or friends) that enhance recipients’ self-esteem or provide stress-related interpersonal aid (Dumont & Provost, 1999). Social support has been known to offset or moderate the impact of stress caused by illness (e.g. Aro, Hanninen, & Paronene, 1989). Support from family has been recognized as vital for elderly people, because it enhances the patient’s physical and emotional functioning (Taylor 2006). In this study, social support will be understood to include perceived support from close relatives or others living with aged person. The family may provide assistance with the day-to-day management and encouragement and support in decision-making (Ford et al. 1998). However, family relationships are not necessarily supportive. Non-supportive family behaviour such as nagging and criticism can reduce people’s perceptions of autonomy, which in turn could make them less motivated to cope with the problems induced by the disease, resulting in increased emotional distress (Deci et al. 1991). Research studies have also shown the importance of social support on the health of the elderly (Rodriguez-Laso, Zunzunegui & Otero, 2007). Different forms of social support exist in facilities where the elderly live. It can be in the form of informal and formal support. Formal support was defined by Litwak (1985) as formal medical services, physician advice and other forms of help from health care personnel, while informal was defined as support given by family members, friends and other close associates. Social support can be in various forms. For this study, emphasis will be on the types of informal support and how it affects depression.There has been a growing interest in the role of informal support in older person’s psychological well-being in both western and Asian societies (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1995). Informal support generally refers to unpaid help given by family, friends, and neighbours (Novak, 1997). However, it is clear that informal support is extensive and can take many forms, including advice, affection, companionship, helping older family members with transportation and nursing care (Kane & Penrod, 1995). Informal support has been held to play a significant role in providing instrumental support (e.g. communications of affection) to older persons, which can involve increasing an older person’s self-esteem, competency, and/or autonomy. The informal support networks of older persons are very important as these networks give residents a sense of belonging. These networks provide older persons with the opportunity to spend time and share activities, with others and the absence of these can contribute to loneliness and depression as previously stated. However, a growing number of studies have documented the beneficial effect of social support on various health outcomes, including survival. This beneficial effect has been confirmed not only in relation to all cause mortality, but also in relation to several causes of death, including cancer, coronary heart disease, and other cardiovascular diseases (Avlund, Damsgaard, & Holstein, 1998; Berkman & Syme, 1979; Blazer, 1982; Brummett et al., 2005; Ceria et al., 2001; Kaplan et al., 1988; Maier & Smith, 1999; Murberg, 2004; Seeman et al., 1993; Seeman, Kaplan, Knudsen, Cohen, & Guralnik, 1987; Temkin-Greener et al., 2004). Although the evidence for the protective effects of social support on health outcomes is growing, the important question of the relevant mechanisms and pathways remains unclear. In addition, it has proved difficult to determine exactly which aspects of social support have been responsible for the beneficial effects on mortality (Walter-Ginzburg, Blumstein, Chetrit, & Modan, 2002). More so, issues of Dysphoric mood or loss of interest or pleasure in life and in free time activities, poor appetite, insomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, feelings of excessive guilt, lack of concentration, inability to think, withdrawn, despondent, disturbed sleep and reduced appetite among elderly people remain concern of psychologist in the field of clinical and health psychology. Past some years, prevalence rates of major depression have steadily increased and the World Health Organization has predicted that by the year 2020 depression will be second only to cardiovascular disease as the leading cause of disability and death worldwide (Murray & Lopez, 1996). Depression might thus be viewed as a severe threat to both “adding years to life” and “adding life to years.” The U.S. Consensus Development Panel of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (2003) recently stated that although safe and efficacious treatments exist, depression still remain a significant health-care issue for older adults. For example, depressive disorder has been found to be a strong risk factor for suicide in the elderly (Wærn et al., 2002). Moreover, natural occurrences and changes associated with the process of aging, such as bereavement, increased loneliness, increased general and physical disability (Bruce, 2001), and declines in cognitive functioning (Boone et al., 1994) are linked to an increased risk of depression.There are many reasons for older adults’ depression. Risk factors for depression stem from multiple sources including death of a spouse or friend, physical impairment, loss of in-dependence, and lack of purpose in life. There is some evidence that depression is a genetic disorder; however, some have argued that a genetic disposition is accompanied by environmental interaction. Worthy to mention are recent incidence studies in Sweden which support the notion that both the prevalence and the incidence of depression increase with age (Pálsson, 2000). Regular physical activity has been recognized by researchers, governing bodies, and organizations such as the World Health Organization (e.g., WHO, 1997) as a way to prevent and treat general illnesses and mental disorders among the elderly. All these studies was conducted in Western and Asian part of the world while little or no studies has being conducted to examine psychological factors as a predictor of depression among elderly people in Nigeria. Therefore, this present study set to examine the influence of coping strategies and social support on depression among elderly people in okeho, kajola local government are of Oyo state, Nigeria.Purpose of the Study The main purpose of this research is to investigates the influence of coping strategies and social support on depression among elderly people in kajola local government are of Oyo state, Nigeria.Research Hypothesis i. Elderly people with low coping strategies will report higher depression compare to elderly people with high coping strategies among elderly people in kajola local governmant area of Oyo state, Nigeria.ii. Elderly people with low social support will report higher depression compare to elderly people with high social support among elderly people in kajola local governmant area of Oyo state, Nigeria.iii. coping strategies and social support will significant independently and jointly influence depression among elderly people in kajola local governmant area of Oyo state, Nigeria.

2. Methodology

- Research DesignThis study utilized cross sectional research design with the use of structured questionnaires. This is because these variables of interest (coping strategies, social support and depression) had already happened or occurred in nature prior to the commencement of the study. The independent variables were coping strategies and social support while the dependent variable is depression.Research SettingThe researchers conducted the study in year 2016 among Elderly people who are 60 (sixty) years old and above, and reside in Okeho, kajola Local Government Area of Oyo State, Nigeria. Okeho settlers came from many directions such as Illaro, Oyo, Tapa, Ondo and Ife to mention but few. They were not originally related beyond the fact of their common Yoruba society. Each had its own customs and they are together to promote their common interest. The history reflects how the settlers found that ancient town in the mid- 18th century, as they were looking for peace and security during the Fulani slave raiders and Jihadists and Idahomey marauders. They found their new home and named Okeho. Farming is their major work. Okeho started as Okeho/Iganna district council in 1955 with thirty six wards in the defunct western region of Nigeria. It became Kajola Local government in 1976 as a result of the local government reforms. Presently, Kajola Local Government has 11 wards. It is about 5,472 sq.km and was divided into two local governments in 1981 thus: kajola west with headquarters at Iganna and Kajola East with Okeho as its headquarters. These two local government areas were remerged in 1983 during the military regime of General Mohammed Buhari. The local government has an estimate landmass of about 4,320 square kilometers. It has 17 towns and numerous villages, which are divided into 11 wards. The 1990 population census provisionally puts the figure of this local government area at 168,260 people. It is bounded in the south by Ibarapa Local Government and Ogun State; in the east by Iseyin Local Government, in the west by Iwajowa local government and Republic of Benin; in the north by Ifesowapo Local Government and in the northwest by Itesiwaju Local Government Area. Study ParticipantsThe participants of the study were elderly people in Kajola Local Government Area of Oyo state, Nigeria. A total number of 200 (two hundred) elderly people were selected using purposive sampling technique which cut across different five geographical locations. A total of 128 (64%) were male while 72 (36%) of them were female. Research InstrumentsQuestionnaires were used to collect relevant information from the participants of the study. The questionnaire was divided into four segments with each of the segments tapping information based on the identified variables of interest. It comprised of four sections; A, B, C and D. The structure of the questionnaire is outlined below;Section A: Socio-demographic VariablesIn this section of the questionnaire, demographic information of the participants were captured ranging from age to their. This section consisted of variables such as age, gender, marital status, and educational status.Section B: Major Depression InventoryThe 10 items version of Major Depression Inventory was extracted from the work Bech P, Rasmussen N-A, Olsen LR, Noerholm V, Abildgaard W (The sensitivity and specificity of the Major Depression Inventory, using the Present State Examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J Affect 2001; 66: 159-164), MDI was used to measure depression among the respondents, it was anchored on 6-point Likert format with response option ranging from All the time (5) to At no time (0). High scores on the scale suggest severe depression. The alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.81. In this study, the researcher reported reliability coefficient of .73 as cronbach alpha for the entire scale.Section C: Perceived Social Support ScalePerceived Social Support Scale was 12-item designed to measure individual perceptions of social support. This scale was extracted shortened version of the original ISEL 40 items developed by Cohen & Hoberman (1983). The scale has three different subscales designed to measure three dimensions of perceived social support. These dimensions are: 1.) Appraisal Support, 2.) Belonging Support, 3.) Tangible Support. Each dimension is measured by 4 items on a 4-point scale ranging from “Definitely True” to “Definitely False”. The alpha coefficient of this scale was 0.72. In this study, the researcher reported reliability coefficient of .69 as cronbach alpha for the entire scale.Coping Strategies Inventory This section of the questionnaire measures coping strategies of elderly people, developed by David L Tobin (1995). The 32 items short version of the coping strategies inventory predicted on 5-point format ranging from; not at all, sometimes, moderately often, often and all the time. This scale was selected because it has been widely used and shown good reliability and validity. In this study, the researcher reported reliability coefficient of .83 as Cronbach alpha for the scale.Procedure for Data CollectionPermission was sought from each of participant by the researchers before the administration of the questionnaires. The purpose of the research work was explained, the researchers then gave copies of the questionnaires to the respondents after explaining the instruction on how to fill the questionnaire. Confidential treatment of information was assured. In all, two hundred questionnaires were distributed (100%), two hundred questionnaires were retrieved (100%), number of questionnaire not use is 0 (0%), No of questionnaires used for data analysis was 200 (100%).Statistical DesignDescriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentage were used to analyze the demographic c haracteristics of the participants. Inferential statistics were used to test hypotheses stated in the study. T-test for independent samples was used to test the first, second and multiple regression was used to test the third hypothesis.

3. Results

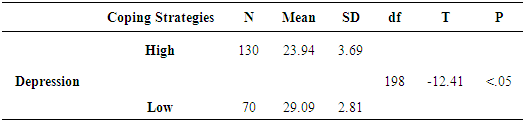

- Hypothesis one which stated that elderly people with low coping strategies will report higher depression compare to elderly people with high coping strategies among elderly people in Okeho, Kajola Local Government Area of Oyo state, Nigeria was tested using t-test for independent measure. The result is presented in Table 1 below;

|

|

|

4. Discussion

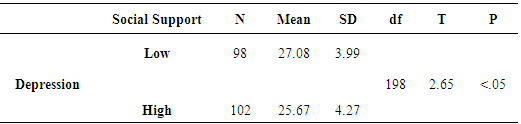

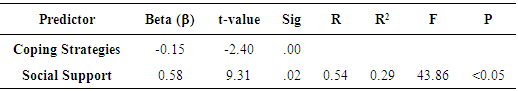

- Depression is another major symptom among the elderly people in Nigeria which can be as a result of many factors. In a cross-sectional study by Barg and colleagues (2006) it was found that in persons 65 years and older, the perceived adequacy of emotional and tangible support was clearly associated with depressive symptoms 3 years later. The greater the adequacy of social support, the lower the depressive scores. This is consistent with the finding of this study as the study tested the predicted hypothesis one which stated that elderly people with low coping strategies will report higher depression compare to elderly people with high coping strategies among elderly people in Okeho, Kajola Local Governmant Area of Oyo state and the result revealed that elderly people with low coping strategies reported higher depression than their counterpart with high coping strategies among elderly [p<.05]. From the result, it was observed that elderly people with low coping strategies had a mean score of 29.09 on depression, while elderly people with high coping strategies had a mean score of 23.94 with a mean difference of 5.15. Therefore, the predicted hypothesis was confirmed. Moreover, this finding was supported by finding of Litwak (1985) who found that both formal and informal support had significant influence on depression among elderly people, when the researcher asked the elderly to describe a depressed person or themselves when depressed. Participants viewed neglect, loneliness as a precursors to depression, as self-imposed withdrawal, or as an expectation of aging. Other studies have substantiated this claim, making lack of social support as one of the strongest predictors of depressed effect. Base on the finding of this study, it appears that older adults who do not have enough quantity and quality of social relations become lonely and this invariably lead to depression and other various forms of health-related issues. Research studies have also shown the importance of social support on the health of the elderly (Rodriguez-Laso, Zunzunegui & Otero, 2007) which supported the finding of this study.One reason that coping strategies contributed to greater functional independence is that a proactive individual is more likely to regard performance of daily activities as a challenge rather than a stressor. This was observed in the result of the finding of this study when tested the predicted hypothesis two which stated that elderly people with low coping strategies will report higher depression compare to elderly people with high coping strategies. The result shows that elderly people with low coping strategies reported higher depression than their counterpart with high coping strategies among elderly people [p<.05]. From the result presented Table 1, it was also observed that elderly people with low coping strategies had a mean score of 29.09 on depression, while elderly people with high coping strategies had a mean score of 23.94 with a mean difference of 5.15. This was consistent with findings Holmes & Stevenson, (1990) that the use of coping strategies produce more favourable outcomes, such as less pain as well as depression, and better quality of life. Also, relying on passive or avoidant coping strategies is associated with increased depression and anxiety (Clement & Schonnesson, 1998). According to Folkman and Moskowitz (2004). There is no clear consensus as to which coping styles are most effective in terms of resolving problems or preventing future difficulties but Lazarus (1991) asserts a close connection between coping strategies and emotional experience. He suggests that self-blaming and avoidant strategies, such as behavioural disengagement, are related to negative emotions depression, whereas more approach oriented coping strategies and seeking social support are associated with positive emotions. Hypothesis three predicted that there will be significant joint and independent influence of coping strategies and social support on depression among elderly people in Okeho, Kajola Local Governmant Area of Oyo state, Nigeria was tested using multiple regression analysis and the result shows that coping strategies and social support yielded a coefficient of multiple correlations (R) of 0.54 and multiple correlations square of 0.29. This shows that about 29% of the total variance of depression was accounted for by the linear combination of coping strategies and social support. The result also indicated that the two independent variables had significant joint influence on depression [p<0.05]. Further analysis revealed that coping strategies and social support made significant independent contribution to depression among elderly people in Okeho, Kajola Local Governmant Area of Oyo State, Nigeria [p<0.05]. This findings was partially supported by an earlier study of Karlsen et al. (2004), who found that emotion-focused styles, coping strategies predict well-being and decreased emotional distress among elderly people. The present finding partially parallel with observations by Carstensen (1992) that selection of emotionally meaningful social relationships may be necessary to elicit the resilience needed for successful adjustment to the difficulties associated with aging. Present findings also coincide with previous research examining social support and coping in relation to depression among the elderly, where it is suggested that coping in the elderly is a key adaptive mechanism through which social support operates (Holahan, Moos, & Bonin, 1997). Additional findings suggest that social support led to lower depression, an expected finding given research supporting this relationship in the elderly (Antonucci & Jackson, 1987). Empirical research has shown that older adults who are embedded in active social networks tend to enjoy better physical and mental health, including lower incidence of depression, than those who do not maintain strong ties with others. The association between depression, social support and coping strategies has been reported as well in longitudinal studies. For example, Holahan & Moos (1986, 1987) found that family support and coping strategies predicted lower levels of depression over 1 year, controlling for previous depression. In a study of 400 patients with chronic cardiac illness, higher levels of social support at baseline were significantly related to fewer depressive symptoms at 1 and 4 year follow ups (Holahan, Moos, Holahan, & Bennan, 1995; Holahan, Moos, & Schaefer, 1996; Holahan et al., 1997). Similarly, findings from a study with outpatients who had rheumatoid arthritis showed that coping strategies and an extended social network predicted a decrease in psychological distress after 1 year (Evers, Kraaimaat, Geenen, & Bijlsma, 1998).

5. Recommendations and Limitation

- The present research has examined the influence of social support and coping strategies on depression among elderly people and has make viable contribution to the understanding of the elderly and their functional ability. Based on this study, the following recommendations are made:It is recommend that family, relative, neighbour and government should provide adequate support to the elderly people in order to reduce depression and mortality among the elderly people as the result of the finding revealed that elderly people with low social support reported higher depression than their counterpart with high social support.Also, It is recommend that family, relative, neighbour and government should empower elderly people to take greater control of their own quality of life because when ask; they said they don't have enough money to eat, government did not provide anything for them and their children are not sending anything to them to put body and soul together. Government and non government organisation should come to assist the elderly people by organise educative and awareness programme to educate and enlighten them on different coping strategies to adopt in order to reduce depression and mortality among the elderly people as the result of the finding revealed that elderly people with low coping strategies reported higher depression than their counterpart with high coping strategies.More so, the present study has made important contribution to the body of knowledge on predictors of depression among elderly people and certain limitation of the study needed to be considered is the study sample. The study considered 200 elderly people in one local governments and one city in Nigeria, so a wider generalization is hindered. Future studies should consider larger sample.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML