-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

2015; 3(1): 1-5

doi:10.5923/j.ijcp.20150301.01

Prevalence of Depression among Resident Doctors in a Teaching Hospital, South East Nigeria

Aguocha Gu1, Onyeama GM2, Bakare MO3, Igwe MN4

1Mental Health Unit, Federal Medical Centre Umuahia, Abia State Nigeria

2Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu State Nigeria

3Child & Adolescent unit, Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Upper Chime, New Haven Enugu, Enugu State Nigeria

4Department of Psychological Medicine, Federal Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State Nigeria

Correspondence to: Aguocha Gu, Mental Health Unit, Federal Medical Centre Umuahia, Abia State Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

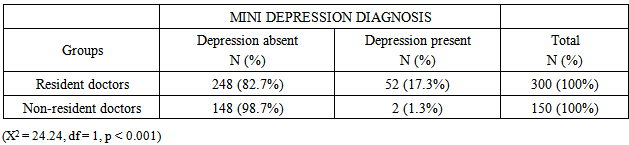

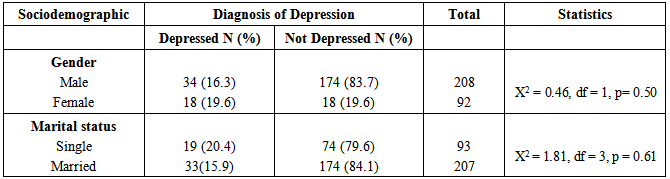

Introduction: The period of residency training is very stressful. Significant among the psychological problems of resident doctors emanating from this high level of stress is depression.Objective: This study determined the prevalence of depression among resident doctors in a training tertiary health institution in Nigeria. Methods: The study was a cross sectional survey of 300 consenting resident doctors at a tertiary training health institution and 150 non-resident doctors working in 3 states, all in south east Nigeria. The participants were interviewed with the socio-demographic questionnaire and depressive module of Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I). Results: The prevalence of depression was 17.3% in resident doctors and 1.3% in non-resident doctors (p < 0.001). Eighteen (19.6%) out of 92 female resident doctors experienced depression compared to 34 (16.3%) out of 208 male resident doctors who had depression (p = 0.44). When marital status was considered 33 (15.9%) out of the 207 married and 19 (20.4%) out of 93 single resident doctors had diagnosis of depression (p = 0.61). Conclusions: There was high prevalence of depression among resident doctors. There were no gender and marital status significant variations in depression among the resident doctors.

Keywords: Depression, Resident doctors, Teaching hospital

Cite this paper: Aguocha Gu, Onyeama GM, Bakare MO, Igwe MN, Prevalence of Depression among Resident Doctors in a Teaching Hospital, South East Nigeria, International Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2015, pp. 1-5. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcp.20150301.01.

1. Introduction

- Medical training has been reported as being stressful [1]. The stress is further increased during the residency training. This is so because of increased expectations and responsibilities [2] and the fact that residents are expected to be proficient clinicians, educators, researchers and administrators at the end of their training [1]. Furthermore, physicians in training experience high level of stress following increase in workload with low control over the job [3]. Significant among the psychological problems of residents doctors include depression, anxiety, fatigue, irritability, substance abuse and sleep deprivation [4, 5].Depression is reported to be common among resident doctors. Depression may seriously affect resident doctors’ professional function and may lead to serious impacts on health behavior of the community in general. A study conducted to determine the rate of depression among resident doctors in Tehran, Iran reported that 31.2% of the total study population had symptoms of depression (26% of the males and 39% of the females). Symptoms of depression were 2.3 times more frequent in females. Unfortunately most of the depressed resident doctors had no history of psychiatric visit or treatment [6].Depression has been reported to be more prevalent in women, including women physicians [7]. Elliot and Girard [8] had posited that the high prevalence of depression and loneliness that female residents experienced was as a result of having to function in a male-dominated profession, having few role models, and being out of synchrony with female peers in general as they pursue the training and delay child bearing. One hundred physicians were compared with 50 lawyers in the State of New York and it was found that 20% of physicians reported depressive illness when inquiry was made regarding their history of illness. Physicians reported more depressive feelings in response to both personal and professional stressors compared to lawyers [9].Thirty percent of medical interns retrospectively reported the experience of significant depression during their internship. Twenty-five percent of these depressed interns reported suicidal ideation; and many had plans to commit suicide [10]. This finding was confirmed by Reuben [11] who reported a 29% rate of depression during the internship year with prevalence as high as 34% during particularly stressful rotations.Furthermore, Schneider and Phillips [12] reported a 35% prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in a cohort of medical, surgical, and pediatric interns. Resident doctors who study or practice medicine in developing countries encounter additional challenges including shortage of health sector budget, low income and disparities in health care distribution. Moreover, the need to study and work simultaneously make them more susceptible to psychological problems such as depression [6].Studies conducted among medical students and residents revealed variable prevalence rates for depression ranging from 2% to 35%; with the higher rates among residents [12, 13-19]. Depression in physicians not only affects their own personal and family lives, but also may have serious impact on health behaviour of the community in general [6]. It may seriously affect physicians’ professional function.Although, residency training programme can be a source of depression in trainees, a study which looked at prevalence of depression among trainee doctors in Ziauddin Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan using the Beck’s Depression Inventory on the contrary, has shown statistically insignificant results regarding depression in trainees. There were no gender based and training level variances (mean ±SD = 9.37 ±10.52 and 8.52 ±7.55 respectively). The authors argued that these results could be indicative of positive reflection of structured training programs resulting in overall wellbeing of the trainees [20].Considering the enormity of depression in studies among resident doctors in developed countries, it is important to find out the prevalence of depression among resident doctors in a developing country. Therefore, this study determined the prevalence of depression and the effect of sex and marital status on depression among resident doctors at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH), Enugu Nigeria. The control group for the study was medical officers (non-resident doctors) of all cadres at the various districts/hospitals of the Hospitals’ Management Boards in Enugu, Imo, and Abia States in South East Nigeria.

2. Methods

- Study settingThis study was conducted among resident doctors at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Ituku-Ozalla. The hospital began early in the 20th century as a general hospital in Ogbete area of Enugu metropolis. At the end of Nigerian civil war in 1970, the then government of East Central State converted it to a specialist hospital. The Federal Military Government in 1974 took over the hospital and constructed a new complex at Ituku-Ozalla. This is located 21 kilometers from Enugu, along Enugu-Port Harcourt express way. The hospital site covers an area of 747 acres. There are 41 main departments with bed capacity of 702. The hospital has about 300 resident doctors.Ethical issuesThe approval to conduct this study was obtained from the ethical committee of University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu State. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants and they were assured of confidentiality and the safety of the data collected.ParticipantsThe participants were all resident doctors undergoing specialist training at University of Nigeria teaching Hospital Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu State Nigeria. Medical doctors who were not in training but were employees of the Hospitals’ Management Boards in Abia, Imo, and Enugu states respectively were used as control. At these various Hospitals’ Management Boards, the no-resident doctors were distributed to the general, cottage and dental hospitals. Twenty medical officers were recruited from Abia state, 65 from Enugu state and 65 from Imo state, making a total of 150 doctors. Instruments for the studySocio-demographic QuestionnaireA socio-demographic questionnaire was used to elicit such variables as age, sex, marital status, religion and ethnic group.The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I) 5.0.0This is a short structured questionnaire that was developed for assessing psychiatric disorders based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10) criteria. It was designed to meet the need for a short but accurate structured psychiatric interview for multicentre clinical trials and epidemiology studies [21]. The Major depressive episode module of M.I.N.I was used for this study.Sample selection and procedureThe list of resident doctors in training and their mobile phone numbers were collected from the office of the president of the Association of Resident Doctors (ARD). Subsequently, contacts were made with each resident doctor to schedule convenient time for interview. Informed consent was obtained followed by administration of the study instruments - Socio-demographic questionnaire and M.I.N.I. by the researchers. The lists of non-resident doctors (control group) and their distribution to various general hospitals were also collected from the directors of Abia, Imo, and Enugu states Hospitals’ Management Boards respectively. The non-resident doctors were also approached on individual basis for informed consent and administration of the study instruments.The interview with each respondent was conducted in a convenient time and place, within the hospital environment. The duration of interview for a respondent was about 20 minutes. Data collection lasted for 9 months.Data analysisThe data analysis was done with SPSS version 16.0. Simple frequency tables were made and Chi-square test, independent sample t-test and logistic regression were used in the analysis of the data. All statistical significance was tested at the 5% level of significance.

3. Results

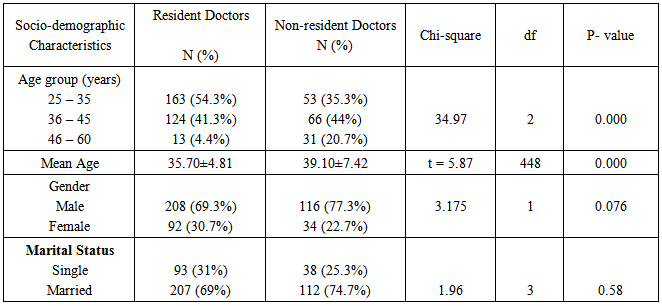

- A total of four hundred and fifty medical doctors were studied. Three hundred (66.7%) of them were resident doctors working at University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Ituku-Ozalla in Enugu State Nigeria. The remaining 150 (33.3%) were non-resident doctors working in hospitals under Hospitals’ Management Boards of Abia, Enugu, and Imo States, all in south east Nigeria.Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants AgeThe age range of the resident doctors was 25-60 years, and the mean age was 35.7 (SD = 4.8). Majority of the resident doctors, 163 (54.3%) were aged between 25-35 years. Those aged between 36-45 years were 124 (41.3%) and 46-60 years were 13 (4.4%). On the other hand, the age range of the non-resident doctors was also 25-60 years with a mean age of 39.1 (SD = 7.4). The age group 36-45 years constituted the majority, 66 (44.0%). Those aged 25-35years were 53 (35.3%), while 46-60 years were 31 (20.7%). There was significant difference in the mean age of the resident doctors and non-resident doctors (t = 5.87, df = 448, p < 0.001).GenderThe resident doctors were made of 208 (69.3%) males and 92 (30.7%) females. The non-resident doctors had 116 (77.3%) males and 34 (22.7%) females (X2 = 3.175, df = 1, p = 0.08).Marital statusTwo hundred and seven (69%) resident doctors were married, while 90 (30%) were never married. Three (1%) resident doctors were either divorced/separated or widowed. One hundred and twelve (74.7%) non-resident doctors were married while 37 (24.7%) never married. Only 1 (0.7%) of them was divorced/separated (X2 = 1.961, df = 3, p = 0.58). Table 1 shows the distribution of the socio-demographic characteristics of the resident and non-resident doctors.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Prevalence of depression among resident and non-resident doctorsThe prevalence of depression among resident doctors was 17.3%. This compares with a previous study conducted in a training hospital in Istanbul by Demir et al [22] who reported the prevalence of probable depression among residents to be 16.0%. However, Goebert et al [23] reported variable prevalence rates for depression among medical students and residents [from all programs/specialties located at six sites (Hawaii, Iowa, California, Cincinnati, Texas and Washington)], to range from 2% to 35%, with the highest rates among residents. Using the center for Epidemiological Studies Scale, Reuben [13] in a longitudinal study in USA showed a peak of 29% of depression in the first year medical postgraduates. Prevalence rates fell with each successive year of training [11].Furthermore, the comparative studies were however, longitudinal and prospective while the present study was cross-sectional assessing point prevalence of depression among resident doctors and the control (non-resident doctors). In the control, the experience of depression was found to be 1.3%. This finding among non- resident doctors was lower than that of the resident doctors. The low prevalence of depression among non-resident doctors could be accounted for by reduced hours of study since there are no professional examinations in view for them, and/or reduced work pressure for the non-resident doctors. The resident doctors on the other hand, are constantly exposed to increased work load and continuous need for reading as examinations are part of the training.Contrary to findings in this study with respect to non-resident doctors, Chambers and Campbell [24] reported 10 percent of depression among the non-resident doctors. Depression ‘caseness’ was associated with having little time from practice work, being single-handed, and working in a non-training practice.Socio-demographic correlates of depression among the resident doctorsThis study showed statistically insignificant results in prevalence of depression between male and female resident doctors. This is in keeping with a study which looked at the prevalence of depression among trainee doctors in Ziauddin Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan which had documented that there was no gender based and training level variations in prevalence of depression among resident doctors [20]. However, this is contrast with other findings showing that depression is more frequent among women (6, 25, 26). The finding in this study with respect to gender may be accounted for by the small sample size of women who were resident doctors (92 female vs 208 male).Also in this study, married resident doctors were not more significantly depressed than single ones. This is in contrast to a study done among resident doctors at Tehran, Iran which documented that married physicians were significantly more depressed than single ones. The authors had attributed this difference to financial pressures and additional responsibilities usually associated with marriage [6]. The finding in this study with respect to marital status may also be accounted for by the small sample size of resident doctors who were single (93 single vs 207 married).

5. Conclusions

- The results of this study indicate that depression is a public mental health problem among the resident doctors.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML