-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2021; 10(3): 80-88

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20211003.03

Received: Jun. 28, 2021; Accepted: Jul. 19, 2021; Published: Jul. 26, 2021

Alternative Dispute Resolution in the Construction Industry: A Case Study of Uganda

Albert Bahemuka

School of Business and Management, Uganda Technology and Management University, Kampala, Uganda

Correspondence to: Albert Bahemuka, School of Business and Management, Uganda Technology and Management University, Kampala, Uganda.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In the real world of the construction industry, disputes are inevitable despite the best endeavors of the contracting parties to avoid them. Matters are not helped by the ill-suited nature of the orthodox legal system toward the resolution of construction industry disputes. It is, thus, imperative that effective dispute resolution mechanisms are in place for the proper functioning of the construction industry. This has added impetus to growing interest in Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). While contemporary literature from other jurisdictions suggested that ADR is most suited to the nature of construction disputes, the effectiveness of ADR in the construction industry in Uganda lacked lucidity in literature. This birthed the need for a research study of this nature. To distinguish facts from anecdotes, this study empirically assessed the real-world effectiveness of ADR in the construction industry in Uganda through a cross-sectional research design, using the quantitative research approach. A questionnaire survey was conducted among 202 respondents drawn from professionally registered construction firms, architectural firms, quantity surveying firms, consulting engineering firms, and reputable client organizations in Uganda. To preclude subjectivity and imprecision, this study measured the effectiveness of ADR against multiple indicators, speed, cost, fairness, preservation of business relations, flexibility, and confidentiality. The study concluded that ADR is an effective mechanism for resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda. Specifically, negotiation was ranked as the most effective ADR technique (d=0.48), followed by mediation (d=0.21) and arbitration (d=0.16). Of significance, this study found that informal ADR is considered more effective than formal ADR. The study recommends the consistent import of ADR provisions into construction contracts, a review of the institutional framework guiding the practice of arbitration in Uganda, and that disputing parties should always explore negotiation options before escalating their disputes.

Keywords: ADR, Arbitration, Mediation, Negotiation, Dispute, Construction

Cite this paper: Albert Bahemuka, Alternative Dispute Resolution in the Construction Industry: A Case Study of Uganda, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 10 No. 3, 2021, pp. 80-88. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20211003.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Construction is a major industry in every country (Saar, Chuing, Hai, & Yusof, 2017, p. 1; Barkai, 2009, p. 1). Uganda is no exception, with conservative estimates from UBOS(a) (2018, p. 104) suggesting the construction sector directly contributed 7.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017/2018. However, as Pena-Mora, Sosa, and McCone (2003, p. 1) offered, the construction industry is unlike any other industry in the world. The typical construction project is complex and lengthy, and given these variables, disputes among parties often occur, expounded AAA(b) (2015, p. 4). Barkai estimated that significant disputes arise in 10% to 30% of all construction projects. There would be no disputes in a perfect construction world, but there is no perfect construction world, Aryal & Dahal (2018, p. 1) concluded.Construction disputes vary in nature, size, and complexity, but they all have a common thread; they are costly both in terms of time and money and are often accompanied by the destruction of individual and good working relationships (Aryal & Dahal, p. 1). The ability to resolve construction disputes quickly and effectively makes the difference between a successful construction project and a failed one, as Mulolo, Alinaitwe, and Mwakali (2015, p. 28) observed. On any construction project, instituting effective mechanisms to resolve disputes is a necessity, not an option.Yiu and Cheung (2007, p. 1) optimistically noted that disputes are, in fact, problems that can be solved if pragmatic and sensible approaches are taken instead of the entrenched confrontational attitude. Formal litigation is thought to be anathema to the goal of most construction participants: to do the most amount of work in the shortest amount of time possible (Gregory & Berg, 2013, p. 17). Rather than truth and justice, adversary litigation produces obfuscation and strategic manipulation (Kruse, 2004, p. 391). Salem (2015, p. 16) observed that the increasing costs, delay, and risk of litigation in construction disputes had pressed the construction industry to search for more innovative and effective means to settle disputes outside the courts. [In lieu of litigation], the global construction industry, today as in past generations, demands efficient, cost-effective, and innovative ADR (Bruner, 2011, p. 9).[Alternative] dispute resolution processes defy neat classification (Riekert, 1990, p. 25). However, many credible authors like USAID, Arcadis (2018), Aryal and Dahal, Idowu and Hungbo (2017), Nkusi (2017), Elziny et al. (2016), Lekkas (2015), EC-Harris (2013), Taylor and Carn (2010), Sternlight (2007), Gould(a) (2004) and Riekert concur with Faris (1995, p. 49) that ADR is founded upon three primary processes: negotiation, mediation, and arbitration constituted into a three-tier dispute resolution system—which Green and Mackie (1995; cited in Gould(b), 2007, p. 3) termed as “the three pillars of dispute resolution.” To be a suitable replacement for litigation, ADR must be effective. Consensus still eludes scholars regarding the measures of the effectiveness of ADR. Mainstream authors like AAA(a) (2018), Khan (2018), Mulolo, Alinaitwe, and Mwakali, Lekkas, Maritz (cited in Raji, Mohamed, & Oseni, 2015), Abdullah (2015), Barough, Shoubi, and Preece (2013), Sayed-Gharib, Lord and Price (2011), Andoh (2010) and Gould(a) have attempted to classify the parameters of ADR effectiveness. Analysis of literature from the previous and various other credible authors informed the deduction in this study that the key measures of the effectiveness of any ADR system could be generalized as cost, speed, fairness, preservation of relationships, confidentiality, and flexibility. Given the movement away from litigation and towards less combative ADR techniques, it is necessary to develop a system to analyze both the quantitative and qualitative impacts of varying dispute resolution selections, recommended Gibson and Gebken (2015, p. 10). To this end, Gibson and Gebken lamented that while there is a significant amount of literature on the qualitative reasons for selecting ADR tools, little quantitative information exists. “The main rationale for ADR was to create a process that was faster and less expensive than litigation…However, there is little empirical evidence to support the effectiveness of ADR”, Harmon (2003, p. 189) equally observed. ADR is a widely discussed discipline within the jurisprudence of construction disputes…[though] few writers venture beyond the normative to consider the reality of ADR, Gould(b) (p. 5) affirmed. Sanford Jaffe (cited in Pincock & Hedeen, 2016, pp. 434-435) concluded that: "Dispute resolution is a field in which research is hurrying to catch up with practice. Developments ... [are] occurring faster than the research can advance to offer guidance and direction."This paucity of empirical evidence warranted a study of this nature. This study sought to assess the real-world effectiveness of ADR in resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda. Whereas previous studies on ADR in the construction industry broadly focused on factors influencing the choice of suitable ADR technique during a dispute, such a comprehensive study on the effectiveness of each ADR technique extends the understanding of how ADR can be efficaciously deployed and therefore is of both academic and practical value.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design and Sampling

- This study was conducted through the cross-sectional research design, using the quantitative research approach. The cross-sectional field survey research design was selected for this study since it is ideal for studies involving a wide population and enables rapid data collection under time and economic constraints. The target population comprises registered construction firms, architectural firms, quantity surveying firms, consulting engineering firms, and client organizations in Uganda. This target population was deemed to have a broad firsthand perspective of the ADR practice in the construction industry. In addition, the target population was anticipated to hold impartial views as these are mere “consumers” of ADR and, apart from utilizing ADR to resolve disputes in which they are disputants, do not derive any other benefits from ADR would introduce bias. Geographically, respondents for this study were drawn from the Kampala region. This accessible population was deemed representative since UBOS(a) reported that, at fifty-five (55) percent, the highest number of construction establishments in Uganda is based in Kampala. To determine the optimum sample size under probability sampling, this study adopted the statistical method postulated by Yamane (1967; cited in Israel, p. 4), which is widely accepted for determining the representative sample size in research. A 95% significance level was adopted for this study; hence, a 0.05 margin of error was considered in sample size computation. Construction dispute resolution is quite a specialist area, with only a small population of potential respondents with sufficient knowledge and experience that can provide authoritative answers (Gill, Gray, Skitmore, & Callaghan, 2015, p. 5). Therefore, only professionally registered firms and reputable client organizations were surveyed to ensure that only credible subjects participated in this study and ensured the findings' validity. Simple random sampling and purposive sampling techniques were deployed to draw the total sample for this study from each stratum.Study respondents from the construction firms, quantity surveying firms, and consulting engineering firms’ subgroups were purposively selected from the accessible population basing on the current registers of the respective professional associations, namely, Uganda National Association of Building and Civil Engineering Contractors (UNABCEC), Institution of Surveyors of Uganda (ISU) and Uganda Association of Consulting Engineers (UACE). From the accessible population of construction firms, only firms registered under class A-1 (Annual turnover above UGX 15 billion), class A-2 (Annual turnover between UGX 15 billion to UGX 10 billion), class A-3 (Annual turnover between UGX 10 billion to UGX 5 billion) and class A-4 (Annual turnover between UGX 5 billion to UGX 1 billion), according to the UNABCEC register of contractors, were selected for this study. This is because firms in the higher turnover ranges execute the more complex projects and are likely the most experienced in ADR use. This was intended to increase the validity of the study findings. The sample of client organizations comprises a selection of government Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs). According to Colonnelli and Ntungire (2018, p. 3), in Uganda, the government is the largest construction client accounting for more than 70% of the total volume of a construction business. Colonnelli and Ntungire further found that central government MDAs in the central region of Uganda [Kampala] account for 94.3% of the total value of government construction contracts. Therefore, a sample comprising of government MDAs in Kampala was sufficiently representative of client organizations in Uganda. Six MDAs with the largest budget allocation for construction, according to Kasaija (2019), were targeted for this survey, namely, Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA), National Water and Sewerage Corporation (NWSC), Electricity Regulatory Authority (ERA), Rural Electrification Agency (REA), Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) and Ministry of Works and Transport (MOWT). Three (3) credible respondents from the relevant department in each target MDAs were requested to participate in this study. In this way, focused information was collected for the study. A sample size of 202 respondents out of the target population of 222 was deemed suitable for this study.

2.2. Data Collection

- Data for this study was collected through structured self-administered questionnaires comprised of close-ended questions. Pre-testing was done to ascertain whether the questionnaires were clear, unambiguous, and relevant through a pilot study of five randomly selected respondents from each stratum of the target population to trial the questions, identify where accuracy could be improved and test the validity of the questions, before mass dissemination of the questionnaires. A content validity index (CVI) of at least 0.70 was considered acceptable, as proposed by Kathuri and Pals (cited in Oso & Onen, 2016, p. 97). After pre-testing, all the items in the survey instrument were found valid, representing CVI=1.00. To further ensure validity, responses from informants who indicated that they are not personally involved in dispute resolution or organizations that responded that they never encounter disputes in their projects were discarded during hypothesis testing on account of being unrepresentative of the phenomenon under study. In this study, the reliability of data was assessed using the internal consistency technique. A reliability coefficient of 0.70 was considered acceptable, as proposed by Kathuri and Pals. All the variables scored alpha values above 0.70, demonstrating that all the constructs in the study instrument were consistent and, thus, reliable.

2.3. Data Analysis

- The data collected using questionnaires were compiled and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), a specialist computer program for analyzing such data. Generalization of the results of this study was then performed using inferential statistics. To test whether the results are statistically significant, a significance level of 0.05 was used. The hypotheses were tested using a one-sample t-test. The one-sample t-test is suitable for hypothesis testing in studies where the independent variable is measured against different indicators, such as the study by Alinaitwe, Mwakali, and Hansson (2009). This study adopted a hypothetical mean value of 3.0 corresponding to the mid-point (neutral) 5-point Likert scale. A p-value <0.05 implied a significant difference between the test value and the population mean. A significant p-value with a positive mean difference implied rejection of the null hypothesis, whereas a negative mean difference implied acceptance of the null hypothesis.Conversely, p-value>0.05 implied indecision among the test population. “Hypothesis testing identifies whether an effect exists in a population. Hypothesis testing does not, however, inform us of how big the effect is…To determine the size of an effect, we compute effect size” (Omebratu, n.d., p. 21). That effect can be assessed by many measures, one of which is Cohen’s d (Skidmore, p. 4). Skidmore elaborated that a value of d between 0 and 0.2 is considered a small effect, between 0.2 and 0.8 is considered a medium effect, and a value of d greater than 0.8 is considered a large effect. According to the values of d obtained, this study drew meaningful conclusions from hypothesis tests.In this study, occurrences and agreement were recorded on a 5-Point Likert scale. Occurrences were measured as; 1-never, 2-rarely, 3-sometimes, 4-most of the time, and 5-all the time. The agreement was measured as; 1-strongly disagree, 2-disagree, 3-not sure/neutral, 4-agree, and 5-strongly agree. Using the appropriate Likert scales, the researcher analyzed the respondents’ opinions, knowledge, and implementation regarding the variables under study. The Likert scale was favored for this study as it allows for more finely tuned responses.

3. Analysis, Results, and Discussion

3.1. Response Rate

- Out of the total 202 questionnaires disseminated, 166 questionnaires were returned, representing a response rate of 82.2%. The response rate per stratum of the sample was: construction firms (80.4%), architectural firms (73.8%), quantity surveying firms (73.1%), consulting engineering firms (93.8%), client organizations (88.9%). Mugenda and Mugenda (Revised, 2003, p. 83) opined that [in scientific research] a response rate of 70% and over is very good and ensures a representative sample for meaningful generalizations. On his part, Etyang (2018, p. 184) recommended a response rate threshold of 67% to guarantee the generalizability of study findings. Hence, it is apt to conclude that, at an 82.2% response rate, the findings of this study are statistically generalizable. Out of the returned questionnaires, no. Three were found unusable and, thus, were not coded for further analysis.

3.2. General Information about Respondents

- Out of the total 163 valid responses received in this study, 50 (30.7%) of the respondents were female, whereas 113 (69.3%) were male. This demonstrates that the sample representation was skewed in favor of males. However, this gender disparity mirrors the norm in the formal sector employment in Uganda, according to UBOS(b) (2018, p. 75). It is, therefore, apt to assert that the sample for this study was representative in terms of gender. Most of the respondents (51.6%) were 36 years old and above. Still, a bigger majority of respondents (96.9%) were 26 years of age and above. This suggests a high likelihood that seasoned industry practitioners participated in this study. A wide majority of the respondents (94.5%) had at least a bachelor’s degree. This is way above the average minimum education requirement for permanent employment in formal sector establishments in Uganda basing on UBOS(b) (p. 56). It is, therefore, appropriate to deduce that very high caliber respondents participated in this study. Most of the respondents in this study possessed significant general experience in the construction industry; 30.7% had over 15 years’ experience, 55.8% had at least 10 years’ experience, and 87.7% had at least five years’ experience. This confirms that seasoned industry practitioners participated in this study. To varying degrees, 96.9% of the informants confirmed that they are involved in dispute resolution. Conversely, (3.1%) of the respondents indicated that they are never involved in dispute resolution. Since this study targeted only respondents with experience in dispute resolution, respondents who possessed no specific experience in dispute resolution were deemed invalid for this study. Hence, data collected from them was not considered for hypothesis testing.

3.3. Disputes in the Ugandan Construction Industry

- To accurately understand the magnitude of the challenge of disputes in the construction industry in Uganda, respondents were asked to provide information such as the prevalence of disputes in construction projects, preference of dispute resolution mechanism, the prevalence of ADR clause in construction contracts, and prevalence of the individual ADR techniques. 98.2% of the organizations surveyed in this study encounter disputes in their projects through varying prevalence rates. It is, therefore, safe to assert that disputes are a normal occurrence in construction projects in Uganda. Since this study targeted respondents with dispute resolution experience, data collected from respondents who indicated that their organizations never encounter disputes was deemed invalid and, thus, not considered for hypothesis testing.98.8% of the respondents indicated that they prefer ADR to litigation in resolving disputes, with none categorically stating they prefer litigation to ADR. This demonstrates that construction industry practitioners in Uganda unanimously favor ADR over litigation in resolving their disputes. 32.7% of respondents indicated that construction contracts include the ADR clause on all projects handled by their organization, 49.4% indicated ‘most of the time,’ 14.2% indicated ‘sometimes,’ and 3.7% indicated ‘rarely.’ It was observed that none of the respondents indicated that all their construction contracts never include an ADR clause. This, therefore, could inform the deduction that providing the ADR clause in construction contracts is a normal practice in Uganda, though not consistent. At 77.3%, most construction industry practitioners in Uganda opt to resolve their disputes by negotiation either ‘all the time or ‘most of the time.’ This suggests that negotiation is the default option in most dispute situations. To varying degrees, a total of 99.4% of the practitioners use negotiation to resolve their disputes. It can, thus, be inferred that construction industry practitioners ordinarily opt to negotiate settlements whenever disputes arise.At a combined 85.9%, most construction industry practitioners in Uganda refer their disputes for mediation either ‘sometimes,’ ‘rarely’ or ‘never.’ This indicates that mediation is an alternative option in most dispute situations. It is observed that, at 1.2%, a drastically lower proportion of construction industry practitioners use mediation in all dispute situations, compared to 34.4% who favor negotiation to resolve all their disputes. Equally, it is observed that, at 4.9%, a considerably higher proportion of practitioners do not establish the need for mediation when resolving their disputes, compared to only 0.6% who disregard negotiation. This strongly suggests that disputes are referred to mediation after exhausting the option of negotiation, as characteristic of a tiered dispute resolution process.At a combined 86.9%, most construction industry practitioners escalate their disputes to arbitration ‘sometimes,’ ‘rarely’ or ‘never.’ Though comparable to the 1.2% who favor mediation ‘all the time,’ at 0.6%, a drastically lower proportion of respondents refer all their disputes to arbitration compared to the 34.4% that opt for negotiation in all dispute situations. Conversely, at 16.1%, a wider proportion of practitioners do not find arbitration an option in resolving their disputes than 4.9% who establish no necessity for mediation and only 0.6% who never engage in negotiation. This trend indicates that arbitration is a second alternative option to negotiation after mediation. In a dispute situation, normally, negotiation is the first option, failure of which the dispute is referred to mediation, and arbitration ultimately. This points to the presence of a three-tier dispute resolution process in the construction industry in Uganda.

3.4. Negotiation and Resolution of Construction Disputes in Uganda

- The first objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of negotiation in resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda. The study employed a six-item instrument to assess the effectiveness of negotiation. Respondents were asked to assess on a 5-point Likert scale the influence of each of the six (6) indicators of effective negotiation on the decision to resolve disputes by negotiation technique. To draw meaningful conclusions from the collected data, statistical analysis was performed in item mean analysis and one-sample t-test.All the items recorded mean values above the ‘neutral’ value of 3.0 on the 5-point Likert scale from the results. Among the parameters of effectiveness, negotiation technique, scored highest on Cost (M=4.53, SD=0.514), followed by Speed (M=4.49, SD=0.552), Preservation of Relationships (M=4.24, SD=0.596), Fairness (M=4.22, SD=0.651), Confidentiality (M=4.15, SD=0.696) and Flexibility (M=4.11, SD=0.703). It is observed that all the parameters recorded mean values above 4.0, which falls between ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ on the 5-point Likert scale. Correspondingly, grand mean value of 4.29 was recorded. This indicates that negotiation was assessed as a very effective approach to resolving disputes in Uganda's construction industry. Moreover, all items recorded standard deviation values below 1.000, which signifies a high level of consensus between respondents.One sample t-test was performed to test the significance level of the items used to assess negotiation effectiveness. The neutral value of 3.0 on the Likert scale was adopted as the test mean. Against all the parameters, at significance level of 0.05, negotiation scored p-value = 0.000<0.05. This showed that there are significant differences between the item mean scores and the test mean. Because the mean differences from the test mean for all the items are positive, the negotiation was, thus, assessed as effective on all the metrics. Hence, the null hypothesis (negotiation is not an effective approach to resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda) was rejected at α=0.05 and 95% significance level.

3.5. Mediation and Resolution of Construction Disputes in Uganda

- The second objective of this study was to establish the effectiveness of mediation in resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda. This was accomplished by asking the respondents to score on a 5-point Likert scale the influence of each of the six (6) indicators of effective mediation on resolving disputes by mediation technique. To draw meaningful conclusions from the collected data, statistical analysis was performed in item mean analysis and one-sample t-test. From the findings of the mean analysis, all the items recorded mean values above the ‘neutral’ value of 3.0 on the 5-point Likert scale. Mean values above 4.0 (‘agree’) were recorded on the parameters of Speed (M=4.25, SD=0.687) and Cost (M=4.24, SD=0.701). The parameters of Flexibility (M=3.54, SD=0.845), Confidentiality (M=3.45, SD=0.925), Preservation of Relationships (M=3.44, SD=0.844) and Fairness (M=3.30, SD=0.986) all recorded mean values between 4.0 (‘agree’) and 3.0 (‘neutral’). A grand mean value of 3.70 was recorded, which tends toward ‘agree’ on the Likert scale. This indicates that mediation is an effective technique of dispute resolution in the construction industry in Uganda. It ought to be noted that standard deviation values below 1.000 were recorded on all items, pointing to strong consensus between respondents.Testing the significance of the items used to establish the effectiveness of the mediation technique in resolving construction disputes in Uganda was achieved by performing a one-sample t-test. The ‘neutral’ value of 3.0 on the 5-point Likert scale was adopted as the test mean to determine the statistical difference between the sample mean and the midpoint of the test instrument. According to the results, for all the test items, at the significance level of 0.05, p-value = 0.000<0.05 was obtained. This confirmed that there are significant differences between the item mean scores and the test mean. Since the mean differences from the test mean for all the items are positive, mediation was, thus, assessed as effective on all the parameters. Hence the null hypothesis (mediation is not an effective method of resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda) was rejected at α=0.05 and 95% significance level.

3.6. Arbitration and Resolution of Construction Disputes in Uganda

- The third objective of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of arbitration in resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda. To achieve this objective, respondents were asked to rank the effectiveness of arbitration based on six parameters on a 5-point Likert scale. To draw meaningful conclusions from the collected data, statistical analysis was performed in item mean analysis and one-sample t-test.Mean analysis shows that the parameters of Cost (M=4.26, SD=0.818) and Speed (M=4.24, SD=0.833) scored mean values between 5.0 (‘strongly agree’) and 4.0 (‘agree’) on the 5-point Likert scale. Confidentiality (M=3.41, SD=0.884), Flexibility (M=3.38, SD=0.888), Preservation of Relationships (M=3.36, SD=0.833) and Fairness (M=3.01, SD=1.053) attained mean values between 4.0 (‘agree’) and 3.0 (‘neutral’). A grand mean value of 3.61 was recorded, which tends towards ‘agree.’ This suggests that arbitration is an effective technique for resolving construction disputes in Uganda. Five of the six items recorded standard deviation values below 1.000, which points to a consensus among the respondents on these items. However, the item on ‘Fairness’ recorded a standard deviation value beyond 1.000, which points to a lack of consensus among respondents on whether ‘arbitration achieves fairness.’To determine the significance of the items used to investigate the effectiveness of arbitration techniques in resolving construction disputes in Uganda, a one-sample t-test was performed. The ‘neutral’ value of 3.0 on the Likert scale was adopted as the test mean to determine the statistical difference between the sample mean and the midpoint of the test instrument. From the results of statistical analysis, five out of the six test items, at a significance level of 0.05, recorded p-value = 0.000<0.05, which confirmed that there are significant differences between the item mean scores and the test mean, at α=0.05, and 95% level of significance. Since the mean differences from the test mean for these five items are positive, arbitration was, thus, assessed as effective on these parameters. Hence, the null hypothesis (arbitration is not an effective technique of resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda) was rejected for the five items. One test item (‘arbitration achieves fairness’) recorded p-value =0.940>0.05, implying no significant differences between the item mean and the test means, at α=0.05, and 95% significance level. This implies the research population is undecided about whether ‘arbitration achieves fairness.’ To confirm whether arbitration was assessed as effective on the aggregate of all parameters, it was necessary to compute the Cohen’s d value since the one-sample t-test did not return p-value = 0.000<0.05 on all test items.

3.7. Cohen’s d Test for the Variables

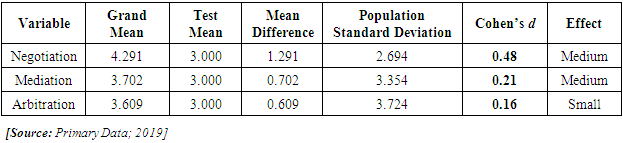

- Cohen’s d test was performed to assess the magnitude of each variable's effectiveness more precisely in this study. From the results, all the variables attained Cohen’s d > 0.00, which confirms that all the ADR techniques assessed in this study ranked as effective. Specifically, negotiation attained Cohen’s d = 0.48. Since 0.2 < d < 0.8, the magnitude of the effectiveness of negotiation was ranked as ‘medium’ according to Cohen’s size effect conventions. Mediation attained Cohen’s d = 0.21. Since, 0.2 < d < 0.8, mediation scored an effectiveness rank of ‘medium’. Arbitration attained Cohen’s d = 0.16. Since, 0 < d < 0.2, the effectiveness of arbitration ranked as ‘small’. The results are presented in Table 1 below:

|

4. Conclusions

4.1. Negotiation and Resolution of Construction Disputes in Uganda

- This study found that negotiation is considered an effective approach to resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda. Negotiation was ranked as the most effective ADR technique. This concurs with the assertion by Taylor and Carn (p. 6) that negotiating disputes is the best course of action. Particularly, negotiation attained the highest rankings on the parameters of cost, speed, and preservation of relationships, in line with Pickavance and Coyne's (2015, p. 10) emphasis that negotiation results in high cost and time savings preserve future working relationships. Unsurprisingly, the negotiation was ranked as the most prevalent technique of ADR in the construction industry in Uganda. Corroborating findings were recorded in contemporary studies conducted in other jurisdictions, as; Khan (p. 82) in UAE, Ansary, and Balogun (2017, p. 5) in Gauteng Province of South Africa, Getahun, Macarubbo, and Mosisa (2016, p. 288) in Ethiopia, as well as Saidu and Gandu (2016, p. 14) in Nigeria. Based on the findings presented herein, this study concluded that negotiation is the mainstream mode of resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda. The study further demonstrated that, as earlier reported by Arcadis (p. 11) and EC-Harris (p. 3), in Uganda, informal ADR (negotiation) is considered more effective than formal ADR (mediation, arbitration) in resolving disputes in the construction industry. This study, thus, concludes that dispute resolution in the construction industry in Uganda is still largely informal.

4.2. Mediation and Resolution of Construction Disputes in Uganda

- The findings of this study informed the conclusion that mediation is an effective method of resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda. Mediation is considered the next most effective form of ADR after negotiation. However, mediation is considered significantly less effective than negotiation and, correspondingly, less preferred in resolving construction industry disputes in Uganda. This is a strong indicator of a tiered dispute resolution mechanism in the construction industry in Uganda. Contrariwise, in South Africa, Bvumbwe and Thwala (2011, p. 35) found that mediation is the most frequently used method in resolving disputes in the construction industry. Likewise, Hogan-Lovells (2016), Andoh, and Love et al. (2007) assert that mediation is the most widely used ADR technique.The low uptake of mediation compared to negotiation is attributed to inefficiencies in the formal institutional framework guiding the practice of mediation, as exemplified by the inconsistent use of ADR provisions in construction contracts in Uganda. Bareebe (2016) similarly observed that the formal institutional framework guiding the practice of ADR in resolving commercial disputes in Uganda is plagued by inefficiencies, accounting for the low traction towards formal ADR techniques.

4.3. Arbitration and Resolution of Construction Disputes in Uganda

- Based on the findings of this study, it was concluded that arbitration is an effective technique for resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda. However, the effectiveness of the arbitration technique was only ranked as “small,” according to the Cohen’s d size effect conventions. In this regard, the findings of this study differ from the conclusion by Agapiou (2011, p. 22) that binding forms of dispute resolution such as arbitration remain the most effective means of resolving construction disputes in the study conducted in Scotland. Equally, the findings of this study contrast with the findings of a study by Mashwama, Aigbovboa, and Thwala (2015, pp. 10-11), in Swaziland, that arbitration is the most effective technique of resolving construction disputes. Similarly, the findings of this study are at variance with the assertion by Eilenberg (2003; cited in Love et al., p. 28) that arbitration is the most widely accepted form of alternative dispute resolution outside the courts. Particularly, construction practitioners were unconvinced that arbitration achieves fair outcomes to disputes. The cause of this construction industry's distrust towards arbitration should attract interest in more focused research and policy intervention. A feasible explanation could be that disputants who escalate their disputes to arbitration evolve a cascading build-up of adversarial attitudes leading to gradual loss of faith in the ADR process. Plausibly still, disputants who reach the arbitration stage will probably be those with innate misgivings about the entire ADR system that is only compelled by contractual obligation to exhaust the ADR process before seeking litigation. Thus, look to arbitration as only a rite of passage to litigation. This line of argument is backed by the observation by RICS (2012, p. 14-18) that many of the standard form contracts contain arbitration provisions which must first be exhausted before proceeding to litigation lest the courts stay litigation proceedings. On his part, Bruner (p. 4) attributes the construction industry’s recent dissatisfaction with the arbitration, in no small part, to the perceived ‘judicialization’ of arbitration. Arbitration has taken on the trappings of litigation, Stipanowich et al. (2010, p. 1) added their voices.On the other hand, the fact that progressively more respondents do not establish the need for arbitration (16.1%), compared to those who do not exhaust the option of mediation (4.9%) in a dispute situation, and those who eschew negotiation (0.6%), further suggests that arbitration is the ADR option of last resort. This confirms the presence of a three-tier dispute resolution system in the construction industry in Uganda, modeled along the stepped dispute resolution process advocated by Stipanowich et al. (p. 44); from negotiation to mediation and, ultimately, arbitration. Furthermore, it concurs with Moustafa's (2012, p. 18) observation that an increasing number of contracts are moving towards the multi-tier dispute resolution system.

4.4. Recommendations

- Based on the conclusion that negotiation is deemed more effective than the formal ADR techniques in resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda, this study recommends that construction industry stakeholders always explore negotiation options before escalating their disputes. Basing on the fact that construction contracts in Uganda do not regularly provide for ADR—deduced from the finding that only 32.7% of construction practitioners indicated that all their contracts include the ADR clause—the researcher recommends that the import of vibrant ADR clauses into construction contracts should be a consistent practice. This will go a long way towards guiding the effective practice of ADR in resolving disputes in the construction industry in Uganda. From the conclusion that, unlike in other countries, construction practitioners in Uganda do not perceive arbitration to achieve fairness in dispute resolution, this study recommends that future researchers and policymakers in the province of construction ADR review the institutional framework guiding the practice of arbitration in Uganda with the view of understanding and alleviating this inefficiency. This will go a long way toward facilitating the effective utilization of arbitration techniques in resolving disputes in the Ugandan construction industry like in other countries.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML