-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2020; 9(5): 154-170

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20200905.03

Received: Oct. 12, 2020; Accepted: Nov. 2, 2020; Published: Nov. 28, 2020

Examining Differences in Motivation Factors between Generation X and Generation Y Construction Professionals in Hong Kong’s Registered General Building Contractors

Mang Yam Lee

Independent Researcher, Hong Kong

Correspondence to: Mang Yam Lee, Independent Researcher, Hong Kong.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This research attempts to examine whether motivation factor differences exist across generation X and Y construction professionals in Hong Kong’s registered general building contractors (RGBC). Recent research demonstrated a paucity of studies on motivation factors of construction professionals of different generations. A thorough literature review was conducted to identify the motivation factors of construction professionals. The findings of the literature review form the base for the constitution of a survey questionnaire used to gather attitudes of both generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals towards the identified motivation factors. 44 generation X and 65 generation Y RGBC’s construction professionals returned the survey. The motivation factors of both generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals are prioritised. By utilising Spearman’s rank correlation, this research found that a weak correlation in the rankings of motivation factors exist across generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals ( ). The hypothesis of this research was thus accepted, concluding that generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals perceive motivation factors differently.

). The hypothesis of this research was thus accepted, concluding that generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals perceive motivation factors differently.

Keywords: Motivation, Generation X, Generation Y, Construction Professionals

Cite this paper: Mang Yam Lee, Examining Differences in Motivation Factors between Generation X and Generation Y Construction Professionals in Hong Kong’s Registered General Building Contractors, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 9 No. 5, 2020, pp. 154-170. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20200905.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

- General building contractor is a people-reliant business. It manages thousands of in-house as well as outsourced workers on site for execution of a building development project, so successful operation of general building contractors is dramatically based on efficient people management [1]. One of the critical elements that composes efficient people management is motivation. With booming Hong Kong’s construction industry over the past few years, general building contractors have a strong demand for construction professionals. Numerous new generation construction professionals have joined general building contractors. This generation is commonly referred to generation Y. With the generation Y workforce joining the general building contractors as construction professionals, the workplace has become multigenerational since three generations, namely, baby boomer, generation X and generation Y, have converged in the workplace at the same time. Public and private sectors typically set age 60-65 as the retirement age, according to Tong et al. [2], so the majority of baby boomer construction professionals will retire from work in the coming years. After the retirement of baby boomer construction professionals, both Generation X and Y construction professionals will become the major part of the construction professionals. Generation Y employees, different from other generation employees, have their own distinctive expectations and view on the corporate workplace [3]. Van Eck and Burger [4] believe the generation Y construction professionals have higher potential productivity since their levels of education are generally higher than that of generation X construction professionals. If the generation Y construction professionals can be adequately motivated, the organisational productivity will be significantly enhanced. A question of whether the factors that motivate generation X to work hard are the same with the factors that motivate generation Y to work hard arises. This question is crucial because high potential productivity can be unleashed if employers are able to recognise what factors can motivate generation Y construction professionals. However, limited research has been conducted on this topic; therefore, research in this regard is needed. General building contractors (RGBC) refer to the contractors that are registered as general building contractors in accordance with Building Ordinance (Chapter 123) in Hong Kong. RGBC is a major employer of construction professionals in Hong Kong. This research concentrates the motivation of generation X and Y construction professionals working in RGBC.

1.2. Aim and Objectives

- The aim of this research is to examine whether motivation factor differences exist between generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals. The research objectives are to:1. Define motivation and generational cohorts, including generation X and Y2. Review motivation theories and generational theories and evaluate their applications in the construction industry or the workplace3. Identify and prioritise motivation factors of both generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals4. Analyse the priorities to find out whether there are differences between them5. Discuss why there are differences or no differences between them

1.3. Hypothesis

- The hypothesis of this research is that motivation factor differences exist across generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivation of Construction Professionals

2.1.1. Background and Definition of Motivation

- Delery and Roumpi [5] state that human resource, which is able to enhance the competitive advantage of organization, is the most valuable organizational resources. Its quality is remarkably affected by motivation since the relationship between job performance and motivation is positive. Aiyetan and Olotuah [6] define motivation as an inner driver that pushes employees towards taking the initiative, continuously modifying solutions to problems and even inspiring others to perform better; Griffin and Moorhead [7], however, prefers describing motivation as an energy to describing it as an inner driver because each human, like a machine, requires fuel to function, but does not require the same type of fuel. Similarly, not every employee is motivated in the same way. Shurrab et al. [8] classify motivation into two types, namely, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Both can influence employee in parallel. Intrinsic motivation refers to an individuals’ need to pride in something and feel competency, such as enjoyment and curiosity while extrinsic motivation refers to a desire to perform an activity in an effort to obtain explicit rewards, such as money and status, or avoid any punishment.

2.1.2. Motivation Theories in the Construction Industry

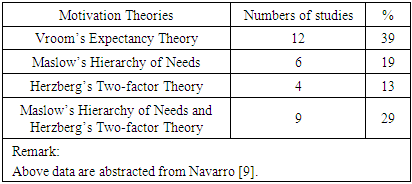

- Navarro [9] searched various international peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings about construction, engineering or project management between 1984 and 2009 and found 31 studies related to testing motivation theories in the construction industries of various countries. Navarro’s [9] result is summarised in Table 1, which supports that Vroom’s Expectancy Theory, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory and Herzberg’s Two-factor Theory are the mainstream of the studies on examination of motivation theories in the construction industry [10,11] and that Vroom’s theory is the most influential process theory in motivation research [12].

|

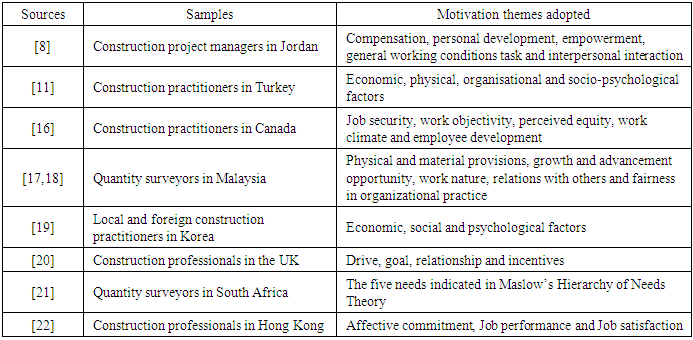

2.1.3. Motivation Themes for Classification of Motivation Factors

- Motivation themes, which are composed of the motivation factors that have similar characteristics or nature, are commonly used to classify the motivation factors to be analysed in studies about the motivation of employees [16]. Table 2 summarises the motivation themes adopted in nine studies published in the past twelve years about the motivation of construction professionals. Among these studies, the motivation themes adopted by Herman and Poon [17] and Herman et al. [18] are the latest and well explained and have the most themes, so this research mainly bases on these motivation themes and also refers the motivation themes adopted in other eight studies to develop the motivation themes to be used in this research for classifying the motivation factors to be explored. The motivation themes developed in this research are physical and material provisions, growth and advancement opportunity, work nature, relations with others and fairness in organizational practices.

|

2.1.4. Motivation Factors of Construction Professionals

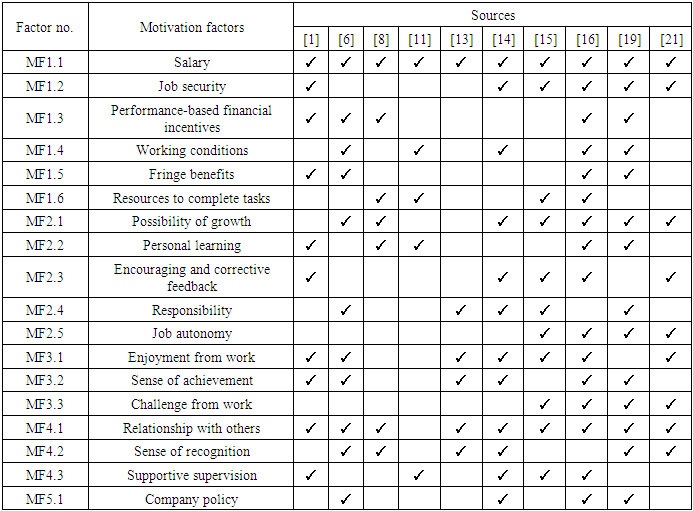

- Motivation factors are the factors that are able to motivate an individual to work harder [23]. The motivation factors of construction professionals vary with their experience [8,13] and culture [19]. For example, sense of achievement become more motivational to the project managers in Jordan when their levels of experience increase [8]. Herman and Poon [17] even point out the motivation factors of construction professionals vary with project stage as different project stages have different natures of work. Therefore, Al-Abbadi and Agyekum-Mensah [15] believe that not every construction professional is motivated in the same way. Nonetheless, the nationality of construction professionals does not affect their motivation factors because no major differences in motivation factors were found between local and foreign construction practitioners in Korea [19] and local and Chinese construction practitioners in Algeria [24]. Also, the gender of construction professionals in Melbourne does not impact their motivation and demotivation level [25]. Moreover, there is no relationship between working hours and motivational levels of construction professionals in Melbourne but a positive relationship between working hours and demotivation levels of construction professionals in Melbourne [1,25]. Through reviewing ten studies concerning investigating the motivation factors of construction professionals in different regions and countries, eighteen motivation factors of construction professionals are identified. In Table 3, these identified motivation factors and their sources are listed. A factor number is assigned to each motivation factor in Table 3 for easy reference.

|

2.2. Generation X and Y RGBC’s Construction Professionals

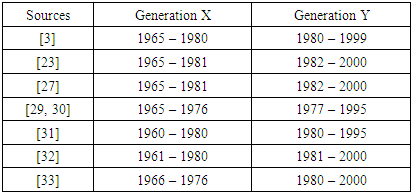

- Haeberle et al. [26] state different generational cohorts have their own group of aspirations, characteristics and perceptions on work, including job satisfaction, the effectiveness of recognition and of reward systems, job expectations and work value, which in turn influence their perception on motivation factors. Similarly, different generational cohorts of RGBC’s construction professionals have different employee perceptions in the workplace. Only little research about different generational cohorts of RGBC’s construction professionals has been conducted. Thus, most of the literature review of generational cohorts in the workplace and generation X and Y in particular are of a general nature. According to Mannheim’s Theory of Generations, generation is defined as an identifiable group of people growing up in the same period and thus shares influential life and historical events at critical developmental stages [23]. It is common to divide employees into five generational cohorts, namely, veterans, baby boomers, generation X, generation Y and generation Z, but there is no unanimous view in the existing literature concerning the birth years that constitute generations X and Y. Despite various ranges of birth years of generation X and Y in eight studies as shown in Table 4, majority of the studies accept generation X was born from around 1965 to 1980 (i.e. 55-40 years old as of year 2020), and generation Y was born from around 1980 to 2000 (i.e. 40-20 years old as of year 2020) [3,23,27]. Therefore, this research also defines generation X as those born from 1965 to 1980 and generation Y as those born from 1980 to 2000. Based on these definitions, Hong Kong’s population of generation X and Y are approximately 1.74 million and 2.07 million respectively as in mid-2019 [28].

|

2.2.1. Differences between Generation X and Generation Y Employees

- As previously mentioned, generation X and Y have their own generational perspectives on work. These unique generational perspectives, including perspectives on motivation, are based on their unique characteristics. Moreover, their unique characteristics are dramatically influenced by historical events at their developmental stages, according to Mannheim’s Theory of Generations. Before looking at how generation X and Y’s perspectives on motivation is shaped by their unique characteristics, it is important to note their unique characteristics as well as significant historical events in Hong Kong.

2.2.2. Characteristics of Generation X and Y Employees

- Although Sir MacLehose, the Governor of Hong Kong, launched a serial of social reforms from 1971 to 1982, these reforms did not have an immediate effect [34]. Generation X lived stressful lives and experienced instability during a series of large-scale riots in 1967. Generation X was grown up as latchkey kids since their living conditions were poor and their parents had to leave their children at home to earn a living [3,27,30,32]. Generation X was used to live independently, which is considered by Bejtkovsky [30] as the most influential experience in the development stage of generation X. This experience develops their independence and self-reliance in the workplace. They prefer working independently to working in a group or team and are not good at interpersonal skills [3]. Kapoor and Solomon [3] also believe generation X is acquainted with multi-tasking and is willing to work on simultaneous tasks as long as the management authorises autonomy to them. Apart from growing up independently, generation X is grown up in a state of instability as mentioned. They prefer status quo rather than a change. Therefore, they resist the change in company policy and job-hopping.According to Yep and Lui [34], the living conditions of generation Y in Hong Kong had been gradually improved because MacLehose’s reforms have taken effect and China has opened its door to the world in the 1980s although they experienced a serial of unstable and uncertain historical events and milestones: Sino-British Negotiations over Hong Kong between 1982 and 1984, Mass Migration Wave between 1980s and 1990s, Handover of Hong Kong from Britain to China and Asian Financial Crisis in 1997. Generation Y is described as a global generation as people from generation Y under the influence of globalisation have similar attributes and characteristics no matter where they come from [30]. In particular, the generation Y in Hong Kong, an international city, absorbs cultures from the world [35]. Utterly different from generation X, generation Y is raised by helicopter parents, paying overwhelming attention to problems, needs and experiences of their children [30], and is used to have group assignments and activities in school [33], so generation Y develops we-oriented and team-oriented characteristics. In the workplace, they have high favour in teamwork but lack work independence [33]. Generation Y was raised with advanced technology [3,23,27,33]. As technology advances rapidly, they are familiar with acceptance and adaption of changes. They feel comfortable with change in company policy and job-hopping [3] and even pursue job challenges and new opportunities [23]. According to Ho [35], generation Y grew up with instant messaging and social networking and hence is also named as the net generation. They expect instant acknowledgement and feedback in the workplace [3].

2.2.3. Motivation Factors of Generation X and Y Employees

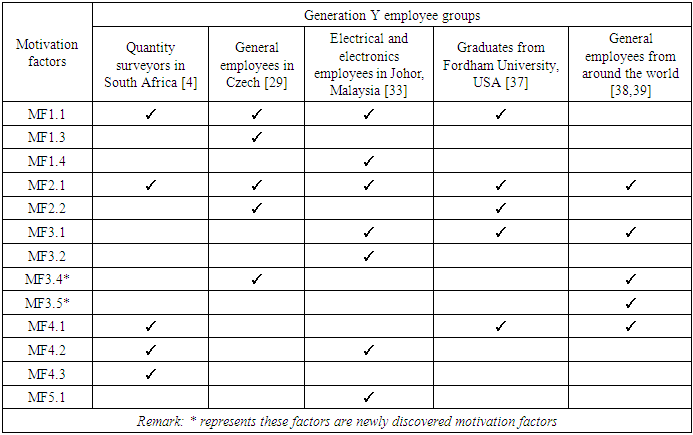

- From the above review of characteristics of generation X and Y employees, it is noted that characteristics of generation X and Y employees are by no means similar as they grew up with different socio-economic conditions. Hence, Smola and Sutton [36] believe the motivation factors of generation X and Y employees are also different. However, Wong et al. [23], Murray et al. [27], Bejtkovsky [29] and Montana and Petit [37] found generation X and Y employees have more similarities than differences in term of motivation factors. For example, Wong et al. [23] found no notable difference in three motivation factors occurs between generation X and Y employees: ease and security, immersion and personal growth while generation Y employees are less motivated by power than generation X employees. Bejtkovsky [29] lists five key motivation factors of both generation X and Y employees and four of them are the same, viz, attractive salary, opportunities for growth, flexible modes of work and self-development and improvement. Montana and Petit [37] lists six key motivation factors of both generation X and Y employees and five of them are the same, viz, attractive salary, opportunities for growth, self-development and improvement, respect from co-workers and opportunity to do exciting work. The only difference is that generation Y is motivated by working well with others, which matches with the generation Y characteristic. Van Eck and Burger [4] researched motivation factors of generation Y quantity surveyors in South Africa. Bejtkovsky [29], Yusoff and Kian [33], Montana and Petit [37], Kultalahti and Viitala [38] and Kultalahti and Viitala [39] also conducted researches on motivation factors of other generation Y employee groups. Table 5 compares the results of all these researches. In general, some factors motivating generation Y quantity surveyors in South Africa correspond with the motivation factors of the other generation Y employee groups, namely, salary (MF1.1), possibility of growth (MF2.1) and relationship with others (MF4.1). Both generation Y quantity surveyors in South Africa and electrical and electronics employees in Johor, Malaysia are motivated by a sense of recognition (MF4.2). Only generation Y quantity surveyors in South Africa is motivated by supportive supervision (MF4.3). Apart from the motivation factors of construction professionals previously identified, two new motivation factors (MF3.4 and MF3.5) are discovered in this comparison, as shown in Table 5. General generation Y employees are motivated by flexibility at work (MF3.4), which includes flexible modes of work and working hours [38,39,29] and work-life balance (MF3.5) [38,39]. Both motivation factors are classified into ‘work nature’ under the motivation themes developed previously.

|

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Method

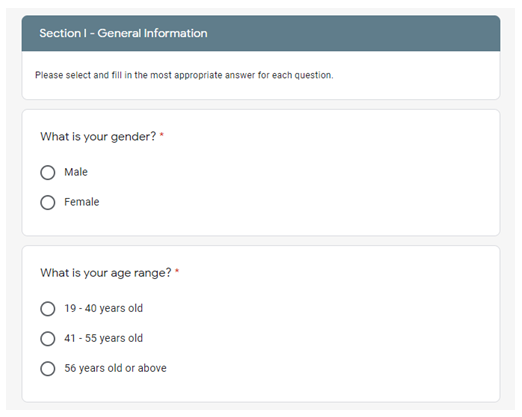

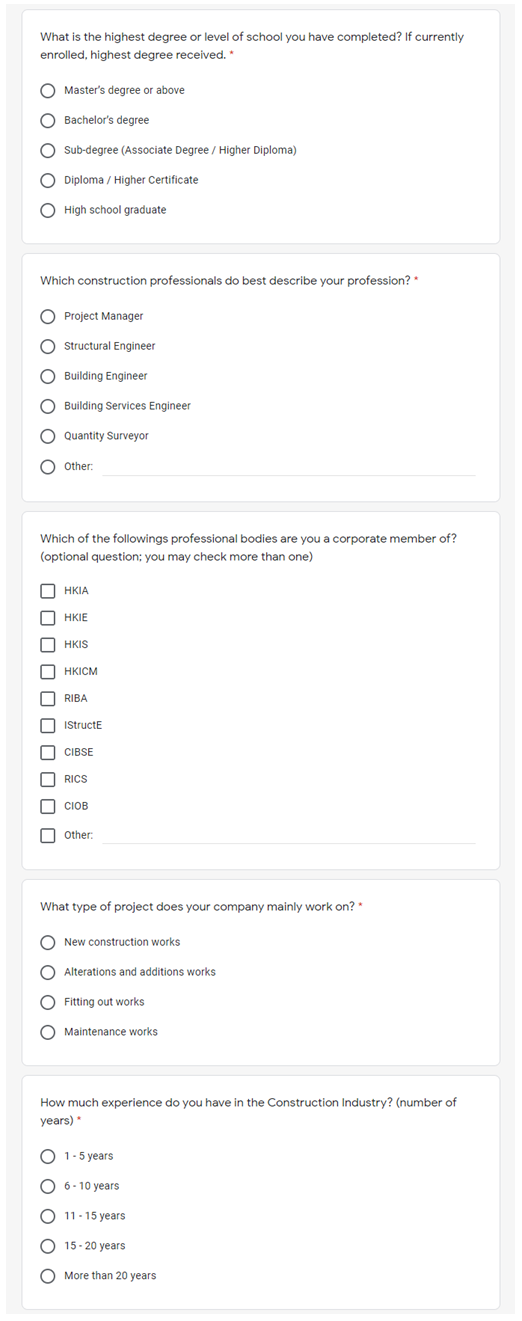

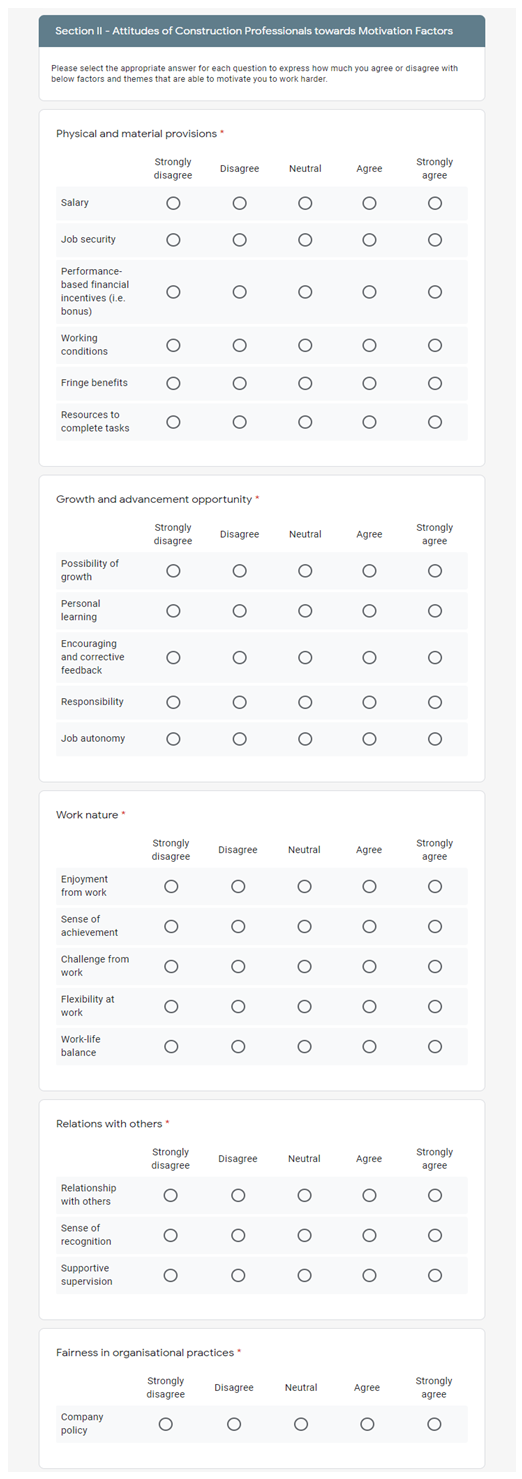

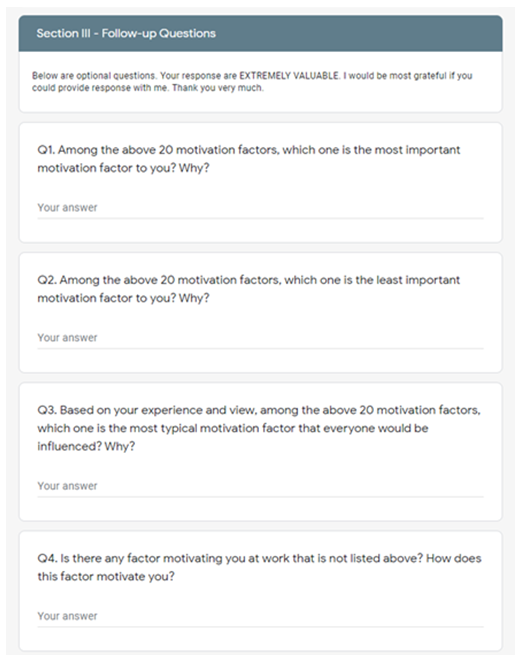

- This research is to examine the motivation factor differences between the generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals, so gathering data about the rankings of motivation factors of both generation X and Y construction professionals is required. This kind of data can be quantified, so questionnaire survey is adopted in this research. A questionnaire is developed from the literature on the motivation of construction professionals and general generation X and Y employees in literature review. The questionnaire comprises three sections. Section I – General Information is to gather demographic data, such as types of construction professionals and age ranges of construction professionals. These nominal data are asked so that the respondents can be classified into either generation X or generation Y RGBC’s construction professionals. Section II – Attitudes of Construction Professionals towards Motivation Factors is to measure attitudes of the RGBC’s construction professionals towards the motivation factors. Eighteen motivation factors of construction professionals (MF1.1 – 3.3 and 4.1 – 5.1) and two motivation factors of general generation Y employees (MF3.4 and 3.5) were previously identified. And, for classifying these total twenty motivation factors, the motivation themes were previously developed. In Section II, the respondents are required to express how much they agree or disagree with these factors and themes motivating them to work harder. Likert scale is used for expression of the level of agreement. The Likert scale for this Section is set as 5-point: Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree and Strongly agree. Section III – Follow-up Questions contain four open-ended questions at the end of the questionnaire requesting respondents to provide the most important, least important, most typical motivation factors with reasons and to provide a motivation factor not mentioned in the questionnaire. To ensure the respondents will find it not complicated to finish the questionnaire, a pilot survey was conducted with two generation X and two generation Y RGBC’s construction professionals before distribution of the questionnaire. All of them expressed the questionnaire is not difficult and time-consuming to rate each of the twenty monition factors. Hence, the questionnaire remains unchanged. The final questionnaire is demonstrated as below.

3.2. Research Population and Sample Size

- The population of this research is all generation X and Y construction professionals employed by RGBC. According to Vocational Training Council [40], building work contractors and decoration, repair and maintenance contractors respectively employed 3,659 and 1,034 construction professionals as in September 2017. These types of firm are considered as RGBC. Hence, the population of generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals is the numbers of construction professionals employed by building work contractors plus the numbers of construction professionals employed by decoration, repair and maintenance contractors. i.e. the population is 4,693. According to Singh and Masuku [41], the sample size for this research population (4,693) is 98 when the population proportion is 0.50, the confidence level is 95% and the precision level is ±10%. Also, random sampling is adopted in this research.

3.3. Questionnaire Distribution

- Most of the RGBC’s construction professionals are able to and are required to use the internet for business operation, so the online survey is adopted in this research. The questionnaire was published on Google Form. The online survey was conducted from 7 December 2019 to 20 December 2019. No comprehensive contact list is available for the RGBC’s construction professionals. Even if some qualified construction professionals can be found on the online directories of professional bodies or registration boards, their contacts are not provided on these online directories. Therefore, the hyperlink for the questionnaire was spread out via email and Instant messaging to the researcher’s classmates, friends and colleagues, and they were invited to forward the hyperlink for the questionnaire to those appropriate people they know.

3.4. Method of Data Analysis

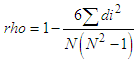

- After the data was gathered, statistical analysis is conducted for analysis of the collected data. Descriptive statistics is applied for the demographic data collected in Section I. A comparative analysis is applied to the questions in Section II. To generate the rankings of motivation factors of both generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals, the collected data are firstly separated into two sets of data, according to the generations of the respondents that are asked in Section I. One set is the motivation factors of generation X respondents. Another set is the motivation factors of generation Y respondents. Both sets of data are then processed in the same way to convert the ratings into rakings as follows. 1. The respondents’ level of agreement on each motivation factor is scored as below: +1 = Strongly disagree; +2 = Disagree; +3 = Neutral; +4 = Agree; and +5 = Strongly agree. 2. For each factor, a mean was calculated based on weightings from (+1) being ‘Strongly disagree’ to (+5) being ‘Strongly agree’.3. Each motivation factor is ranked according to their means.4. Priority is achieved by giving the priority ‘1’ to the motivation factor with the largest mean, ‘2’ to the motivation factor with the second-largest mean and so on. The rankings of twenty motivation factors of generation X and Y respondents are generated. To discover whether the difference in the rankings of motivation factors exists between the generation X and Y respondents, the rankings of the motivation factors between the generation X and Y respondents are tested by using Spearman's rank correlation (

) because this non-parametric test is to measure the difference in rankings between two groups of respondents’ scoring a number of factors [42]. Spearman's rank correlation is presented mathematically as below:

) because this non-parametric test is to measure the difference in rankings between two groups of respondents’ scoring a number of factors [42]. Spearman's rank correlation is presented mathematically as below:  | (1) |

= the difference in ranking between each pair of factors

= the difference in ranking between each pair of factors = number of factorsThe research hypothesis is that motivation factor differences exist across generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals. By implication, the null hypothesis is that motivation factor differences do not exist across generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals. The coefficient (

= number of factorsThe research hypothesis is that motivation factor differences exist across generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals. By implication, the null hypothesis is that motivation factor differences do not exist across generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals. The coefficient ( ) always is between 1.0 and -1.0. The closer

) always is between 1.0 and -1.0. The closer  is to ±1, the stronger the likely correlation. A perfect positive correlation is +1, and a perfect negative correlation is -1. Saunders et al. [43] specify the absolute values of

is to ±1, the stronger the likely correlation. A perfect positive correlation is +1, and a perfect negative correlation is -1. Saunders et al. [43] specify the absolute values of  as: ±0.00-0.19: very weak correlation; ±0.20-0.39: weak correlation; ±0.40-0.59: moderate correlation; ±0.60-0.79: strong correlation; and ±0.80-1.00: very strong correlation. Thus, if the resulted

as: ±0.00-0.19: very weak correlation; ±0.20-0.39: weak correlation; ±0.40-0.59: moderate correlation; ±0.60-0.79: strong correlation; and ±0.80-1.00: very strong correlation. Thus, if the resulted  is equal to or less than ±0.39, the hypothesis will be accepted, and the null hypothesis will be rejected.

is equal to or less than ±0.39, the hypothesis will be accepted, and the null hypothesis will be rejected.4. Data Analysis

4.1. Return of Questionnaire

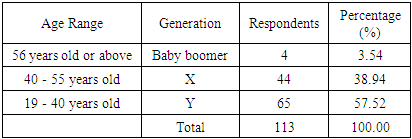

- After the two-week-response period of the online survey, a total of 158 RGBC’s construction professionals were invited to participate in the survey. 113 of them completed the online survey. The response rate is 71.52%. Because all questions in the online survey were set as compulsory, no incomplete questionnaire was received. The proportion of generation X and Y respondents is a critical aspect that was considered for statistical analysis as this research attempts to compare the generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals. Table 6 demonstrates the respondents’ age group and also classifies their respective generations. As the number of baby boomer respondents (only four respondents) is not representative, so the data from baby boomer respondents are not considered in this research.

|

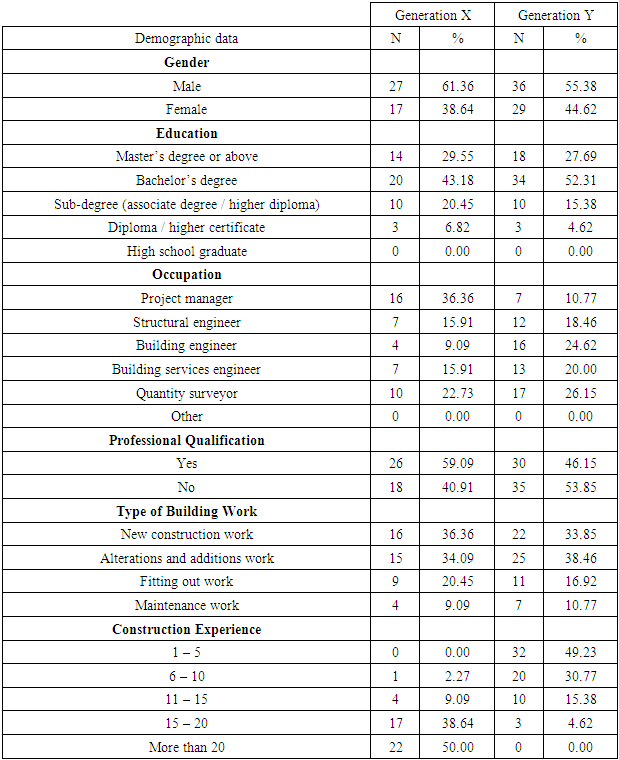

4.2. Demographic Data of the Respondents

- This section presents the findings from Section I of the questionnaire survey, which attempts to collect the demographic information of the respondents. This information is critical in providing readers with a basic understanding of the respondents. This research attempts to compare the generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals, so the collected data including demographic data are separated into two sets of data, according to their generations, for comparison and analysis. One set of data is from the respondents of generation X RGBC’s construction professionals (40 - 55 years old). Another set of data is from the respondents of generation Y RGBC’s construction professionals (19 - 40 years old). Accordingly, the following demographic data of the generation X and Y respondents are separately presented in Table 7.

|

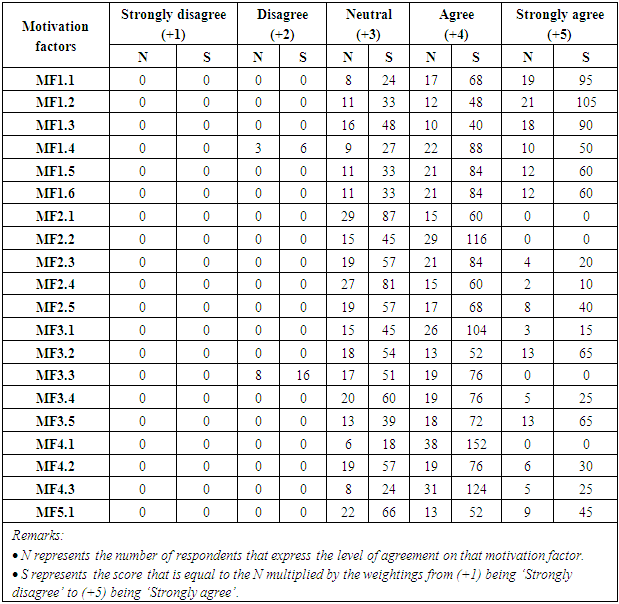

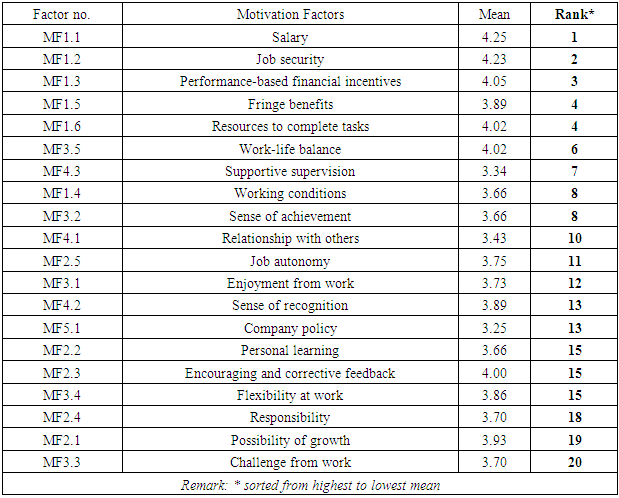

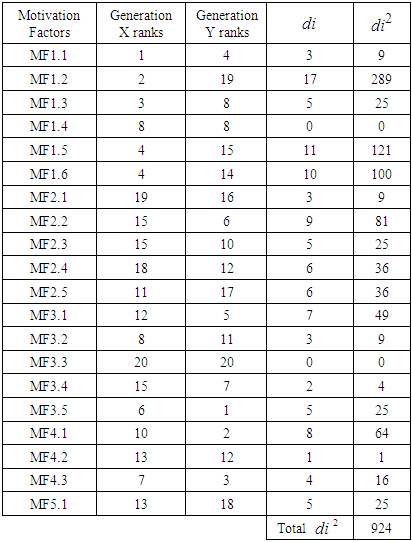

4.3. Factors Motivating the Generation X Respondents

- The data gathered from Section II of the questionnaire survey regarding the level of agreement on the factors that are able to motivate the generation X respondents to work hard are presented in Table 8. Based on the data in Table 8, mean is calculated and demonstrated in Table 9. The motivation factors are prioritized from highest to lowest mean in Table 9.

|

|

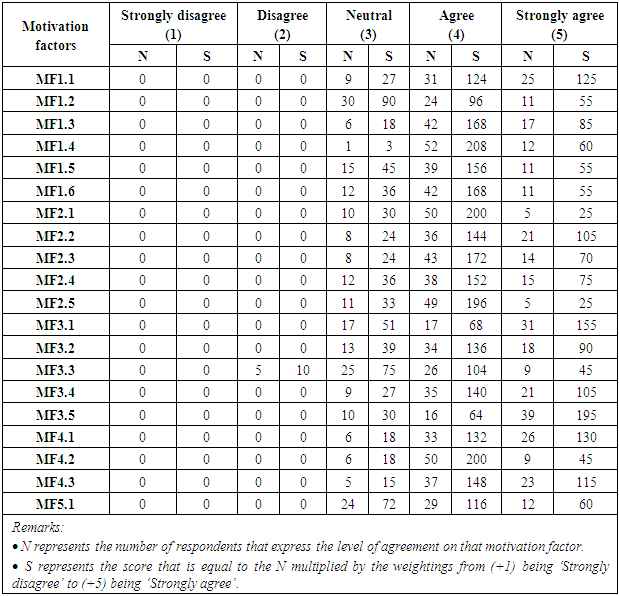

4.4. Factors Motivating the Generation Y Respondents

- The data gathered from Section II of the questionnaire survey regarding the level of agreement on the factors that are able to motivate the generation Y respondents to work hard are presented in Table 10. Based on the data in Table 10, mean is calculated and demonstrated in Table 11. The motivation factors are prioritized from highest to lowest mean in Table 11.

|

|

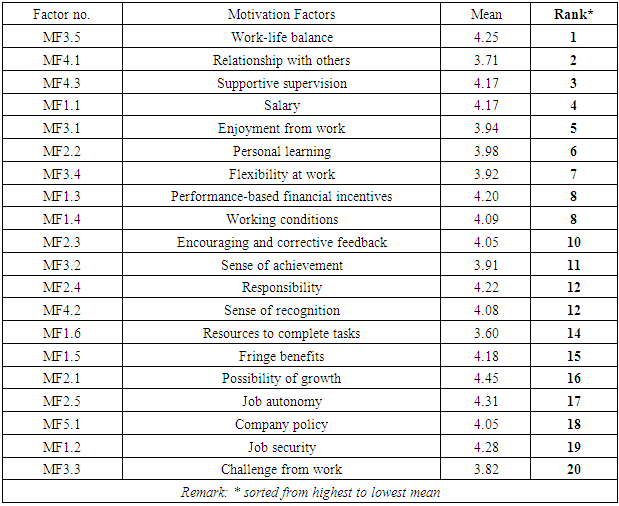

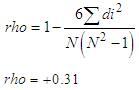

) is used to test whether the difference in the ranking of motivation factors exists between the generation X and Y respondents. Put 924 from Table 12 into

) is used to test whether the difference in the ranking of motivation factors exists between the generation X and Y respondents. Put 924 from Table 12 into  and 20 into

and 20 into  ,

, | (2) |

is +0.31, indicating that there is a weak correlation in the ranking between the motivation factors of the generation X and Y respondents, according to the absolute values of

is +0.31, indicating that there is a weak correlation in the ranking between the motivation factors of the generation X and Y respondents, according to the absolute values of  mentioned in the Methodology. High ranking by the generation X respondents to the motivation factors does not correspond to high ranking by the generation Y respondents to the same factors. Thus, the hypothesis can be accepted, concluding that generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals perceive motivation factors differently.

mentioned in the Methodology. High ranking by the generation X respondents to the motivation factors does not correspond to high ranking by the generation Y respondents to the same factors. Thus, the hypothesis can be accepted, concluding that generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals perceive motivation factors differently.

|

5. Conclusions

- Through the literature review, eighteen factors motivating construction professionals were identified in the studies related to investigating the motivation factors of construction professionals, as presented in Table 3. Furthermore, the additional two factors motivating general generation Y employees are also identified in the studies in respect to exploration of the motivation factors of general generation Y employees, as demonstrated in Table 5. These total twenty motivation factors were categorized into five motivation themes according to their natures. 113 RGBC’s construction professionals returned the questionnaires. 38.94% of them are generation X while 57.52% of them are generation Y. And, the rest of the respondents are baby boomers. The rankings in motivation factors of generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals are presented in Table 9 and 11 representatively. A general observation indicated that no respondent expressed disagreement or strong disagreement on those twenty motivation factors, except working conditions (MF1.4) and challenge from work (MF3.3). In other words, almost all motivation factors have an influence on the respondents to a certain extent. For generation X respondents, salary (MF1.1) is the most influential motivation factor. Seven generation X respondents expressed salary is an indispensable element for living. For generation Y respondents, work-life balance (MF3.5) is the most influential motivation factor. Three generation Y respondents emphasized that work is just a part of life. Challenge from work (MF3.3) is the least influent motivational factor for both generation X and Y respondents. Both generation X and Y respondents expressed that no award can be received for overcoming challenges from work. By using Spearman's rank correlation to test the hypothesis that there are differences in motivation factors of both generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals, this research found that a weak correlation in the rankings of motivation factors exists across generation X and Y RGBC’s construction professionals because the

is +0.31. Thus, the hypothesis can be accepted, concluding that generation X and generation Y RGBC’s construction professionals perceive motivation factors differently.

is +0.31. Thus, the hypothesis can be accepted, concluding that generation X and generation Y RGBC’s construction professionals perceive motivation factors differently.  Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML