-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2020; 9(5): 135-141

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20200905.01

Received: Sep. 10, 2020; Accepted: Oct. 2, 2020; Published: Oct. 26, 2020

Differential Pricing of Concrete Products within the Ghanaian Construction Industry

E. K. Nyantakyi1, N. K. Obeng-Ahenkora1, A. Obiri-Yeboah2, G. A. Mohammed2, M. K. Domfeh1, R. K. Osei3

1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Energy and Natural Resources, Sunyani, Ghana

2Department of Civil Engineering, Kumasi Technical University, Ghana

3Department of Construction and Wood Technology, University of Education Winneba, Kumasi, Ghana

Correspondence to: E. K. Nyantakyi, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Energy and Natural Resources, Sunyani, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Concrete is an essential widely used material in the construction industry worldwide. Notable concrete products used in Ghana’s construction industry are precast septic tanks, box and pipe culverts, fence posts, concrete poles, roof tiles, precast beams and columns, pavement blocks and slabs etc. Though the variety is large, there exists significant price disparities for the same materials across markets in Ghana. This study assessed differential pricing of concrete products on the Ghanaian construction market with the objective of ascertaining the determinants and causes of differential pricings, and the effects of these differentials on the construction industry in three major cities (Accra, Kumasi and Sunyani) in Ghana. Price data was collected, collated and analyzed from the three cities and the determinants, causes and effects of differential pricings were assessed and ranked based on existing literature. An overall assessment indicated that the main determinant of differential pricings was material input, whereas cost of production was the highest ranked cause of differential pricing. Uncertainties during project estimation which include taxes was also seen to be the highest ranked effect of differential pricing. It is recommended that drastic steps be taken by Government to reduce the uncertainties such as subsidizing some taxes on the importation of raw materials and the use of other inputs in producing concrete products.

Keywords: Ghanaian construction industry, Concrete, Accra Metropolis, Kumasi Metropolis, Sunyani Municipality, Differential pricings

Cite this paper: E. K. Nyantakyi, N. K. Obeng-Ahenkora, A. Obiri-Yeboah, G. A. Mohammed, M. K. Domfeh, R. K. Osei, Differential Pricing of Concrete Products within the Ghanaian Construction Industry, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 9 No. 5, 2020, pp. 135-141. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20200905.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Concrete plays a vital part in our daily lives in any functioning society. It’s benefits to society are immense; they are used to build schools, hospitals, apartment blocks, bridges, tunnels, dams, sewerage systems, pavements, runways, roads and many more (Baikerikar, 2018). Twice as much concrete is used around the world than the total of all other building materials, including wood, steel, plastic and aluminum (Petkar, 2014). Few people realize that concrete is in fact the most widely used fabricated material in the world, with nearly three tons used annually for each man, woman and child (Morsali, 2019). No other material can replace concrete in terms of its effectiveness, price and performance. To put it simply, Banthia et al, (2014) wrote “concrete is the material mostly used in the construction industry and is one of the foremost strong building materials”. It gives predominant fire resistance compared with wooden structures and picks up quality over time. Concrete is a blend of smashed stone, sand, cement and water that solidifies as a result of chemical responses between the cement and water (Kumar, 2009). Additionally, it is the basis of an expansive commercial industry, with all its positive and negative properties. Within the United States alone, concrete generation may be a $30 billion per year industry, considering, as it were, the esteem of the ready-mixed concrete sold each year (Syverson, 2008). Designers from around the globe incorporate concrete products in construction projects ranging from commercial and educational through to residential. Concrete products used in the construction industry could be precast concrete beams, pavement slabs, wall copings, precast columns, concrete curbs, concrete pavement blocks, prestressed concrete pressure pipes (PCCP) and concrete hollow and solid blocks (Lopez-Mesa et al. 2009). Given the measure of the concrete industry, and the basic way concrete is utilized to shape the foundations of the construction world, it is troubling to underrate the part this fabric plays nowadays. Most developing countries including Ghana, face acute housing problems, especially in the larger cities (Atiemo, 2013). The degree of housing shortage varies from location to location and has indirectly contributed to the varying prices of concrete products and components. In marketing, a product is anything that can be offered to a market that might satisfy a want or need (Kotler and Amstrong, 2011). Prices of concrete products are dictated by components of the economy other than components that trigger prices of these products in the construction industry. Field and Ofori (1988) stated that construction makes a clear contribution to the economic output of a country; it generates employment and incomes for the people. Relatively, the effects of changes within the housing industry on the economy occur in the least levels and in virtually all aspects of life (Chen, 1998; Rameezdeen et al, 2006). Most contractors in the industry are victims of various price differences on individual concrete products. Difference in prices in various cities affects contractors tendering processes for different localities. Today, most construction works have been abandoned due to rapid and varying prices of concrete products. The initial perception fails to take into account the negative impact of the variation in prices throughout the construction process. Different prices will result in delays of consumers’ plan to build houses, add more rooms and renovate (Dipasquale, 1999). Shekhar (2013) discovered various factors responsible for pricing building materials such as cost of production, competition, product substitution, exchange rate and demographics. Cost of product or service is an important consideration for pricing decisions. Total cost includes cost of raw materials, labour, transportation cost, fixed cost and variable cost among others. For the short term, recovery cost may be ignored in order to capture maximum market share. In case of monopoly or less competition, international companies could set high prices. However, in case of intense competitions, lower prices may be set. Non-availability of substitute products will obviously lead to high pricing. Nevertheless, if there are better and cheaper substitute products, prices will be forced downward. Different currency exchange rates result in different values at different times thereby affecting product pricing. Demographics of targeted customers will indisputably influence pricing of products. Demographic factors to consider before product pricing include targeted age bracket of customers, business location and educational status among others. Differential pricing allows retailers to gain sales and profits (Yuan-shuh and Erin, 2009). According to Carrol and Coates (1999), most industries and companies adopt this technique of varying prices of the same product based on customer location. This is purposely aimed at gaining higher rates of profit from the market. Differential pricing is used in solving production issues. Prices of products are set to aid in establishing sales ratios which may subsequently reflect production ratios (Odlyzko, 2003). Differential pricing is the strategy of selling the same product to different customers within different locations at different prices. It can also mean charging relatively higher rates to customers who have fewer competitive options than to customers with more competitive options (A.A.R, 2013). The most straightforward form of differential pricing consists of charging different consumers different prices to access the same good or service. A more subtle form consists of charging different consumers different prices for different versions of the same good or service when the price gap is greater than can be explained by differences in the cost of the versions (Huan and Jianhua, 2013). The immediate impact is that it increases the bid prices (Miti and Chanda, 2013) and creates competitions among contractors and suppliers. The essence of this research is to investigate and determine the various derivatives affecting differences in concrete product pricing in the Ghanaian construction industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Study Sites

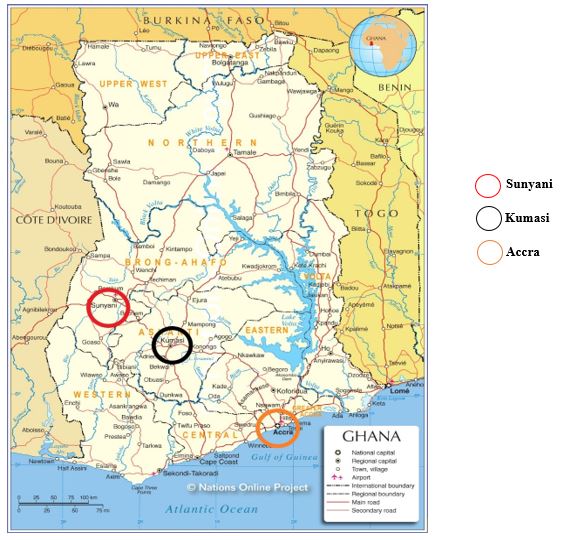

- Accra, Kumasi and Sunyani (see Figure 1) were cities in Ghana selected for the study. These study areas were chosen due to their active participation in the construction industry in Ghana. Accra and Kumasi, the two most populous cities, have hosted a lot of high profited construction projects in the country which demanded the use of huge volumes of concrete and concrete products. Differential pricing has either created positive or negative impacts on construction projects undertaken in these cities. Also, Sunyani has turned out to be one of the areas now encountering a lift in the construction industry with a great deal of progressive developmental works. It has already encountered some overwhelming development works such as the Ultra-Modern Regional Hospital, the Sunyani Coronation Park, the Jubilee Park, the Cocoa Board Building and Queen of Peace Building among others. Sunyani was also chosen because of its current involvement as a new player in the construction industry so as to keep a proper balance while removing all bias.

| Figure 1. Map of Ghana showing the study areas used for the study |

2.2. Methods of Data Collection

- Questionnaires were administered to stakeholders and designers in the construction industry in the three cities (Accra, Kumasi, and Sunyani) studied. Respondent selection was stratified based on study area population. Due to the inability to determine the actual sample size for the research, purposive sampling method was adopted. Questionnaires were designed to gather information on respondent demographics, determinants, causes, effects and prices of concrete products on the construction industry market.

2.3. Data Analysis

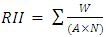

- A total of 475 questionnaires were distributed to concrete product sellers and 394 were retrieved representing a response rate of 82.95%. This was considered adequate for the analysis based on the assertion by Moser and Kalton (1971) that the result of a survey could be considered as biased and of little value if the return rate was lower than 30-40%. Data retrieved were then analyzed using Relative Importance Index (RII) and correlation.

| (1) |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Socio-demographic and Work-related Characteristics of Respondents

- The considerations were age and experience in the construction industry, career and occupation. These were chosen because they were deemed to have influence on peoples’ perception.

3.1.1. Experience in the Construction Industry

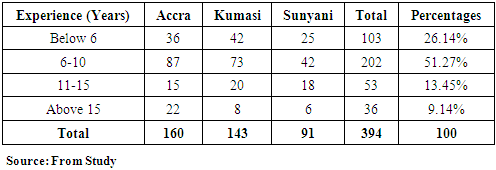

- The study conducted in the three cities showed the following results, presented in Table 1.

|

3.1.2. Career or Occupation

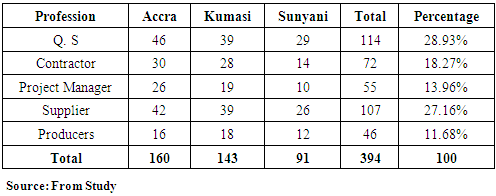

- The study was conducted in three demographical areas and Table 2 depicts the profession of the respondents.

|

3.2. Determinants of Differential Pricing of Concrete Products

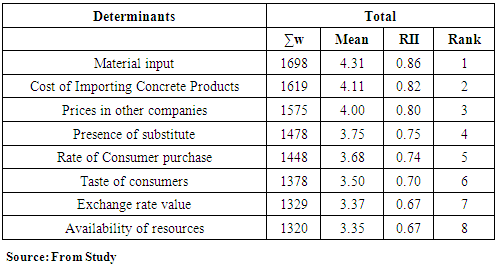

- Respondents were asked to rank possible factors based on frequency of occurrence according to their own judgment and experience in the Ghanaian construction in the three cities. RII was computed as shown in Table 3. Respondents were required to rank each determinant on a scale of 1-5, where 1 = Highly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree and 5 = Highly agree. With an RII of 0.80, the three determinants of differential pricing in order of importance are material input, cost of importing concrete products and prices of products in other companies.

|

3.3. Causes of Differential Pricing

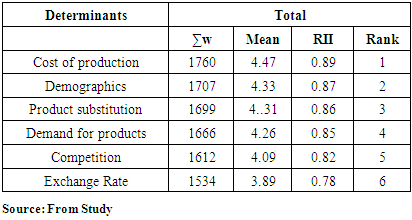

- The respondents were asked to rank factors based on frequency of occurrence according to their own judgment and the experience in the construction industry. The results are shown in Table 4.

|

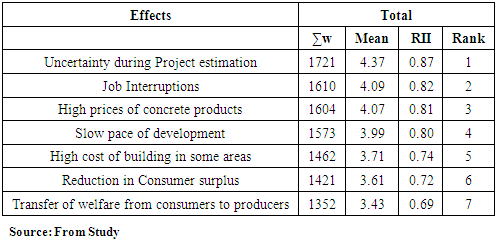

3.4. Effects of Differential Pricings of Concrete Products

- Respondents were asked to rank factors based on frequency of occurrence according to their own judgment and experience. Results is shown in Table 5.

|

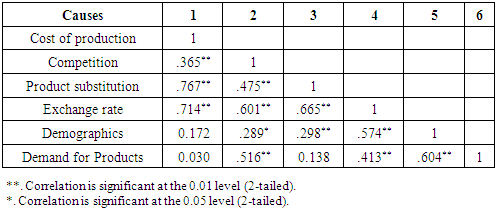

3.5. Relationship between Causes of Differential Pricing of Concrete Products

- The causes of differential pricing of concrete products were subsequently analyzed using a simple bivariate correlation to determine the level of relationship and their impact on one another. Table 6 displays the results of a two tailed spearman correlation matrix to determine the direction of the relationship.

|

4. Conclusions

- Concrete products are widely used in the construction industry. Respondents (with more than six years industry experience) are all building professionals in the industry and have reliable knowledge on the products. Majority of respondents are of the view that material input largely determines prices of concrete products. None of the respondents gave any critical factors under determinants, causes and effects apart from what has already been established in literature. The main impact of concrete differential pricing is uncertainty in project estimation. It could also be concluded that there are various price determinants of concrete products, which in turn adversely affect the construction industry.

5. Recommendations

- It is recommended that steps should be taken by Government to control the factors that determine prices of concrete products in Ghana by setting up legislations to control pricing of these products. Government should subsidize some taxes on the importation of raw materials and the use of other inputs in the production of concrete products so as not to overburden the end user of the product and also reduce the rate at which prices of concrete products fluctuate and escalate.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML