-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2020; 9(3): 99-106

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20200903.03

Received: July 21, 2020; Accepted: August 3, 2020; Published: August 15, 2020

A Strategic Model for Mitigating Construction Workforce Shortages in South Western Nigeria

Oluwole Joseph Oni

Department of Quantity Surveying, Federal Polytechnic, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Oluwole Joseph Oni , Department of Quantity Surveying, Federal Polytechnic, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Nigeria grapples with enormous housing and infrastructure deficit and efforts to bridge the gap have been constrained by the acute shortages of construction workforce. This study addresses the shortages of construction operatives in the Nigerian construction sector. The study area for this research is South Western Nigeria. Questionnaire survey was adopted for this study and simple random sampling techniques were employed. The mean score was employed as a tool for analysis. Findings indicate that there is need for significant improvement with respect to integration, industry participation, funding, recruitment and policy interventions. It was also found that building synergies among key stakeholders and adopting best practices is germane to mitigating the current workforce challenge. The study develops a strategic model to mitigate the current workforce shortages in the sector. The model serves as an enabler towards effective synergies among key stakeholders; reforming key policies; reviewing priorities; reassessing roles; reallocating resources and building stronger collaboration across traditional boundaries to resolve the workforce challenge.

Keywords: Construction workforce, Mitigation, Shortages, South Western Nigerian, Strategic model

Cite this paper: Oluwole Joseph Oni , A Strategic Model for Mitigating Construction Workforce Shortages in South Western Nigeria, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 9 No. 3, 2020, pp. 99-106. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20200903.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The workforce shortages confronting the Nigerian construction sector poses an impending danger to the sector if urgent steps are not taken to mitigate the problem. Construction employers and developers face difficulties in sourcing skilled workmen needed for construction projects. This workmen shortages has necessitated outsourcing the services of the construction artisans from neighbouring nations such as Republic of Benin.This development has exacerbated the socio-economic problems of the nation especially unemployment. As the nation continues to struggle with rapid population growth, housing and infrastructure problem become more acute especially as the supply cannot match with the demand. Essentially, construction operations are still heavily dependent on manual labour (Sanni and Alabi, 2008). Therefore, adequate mechanisms for training and supply of the required workforce are crucial for effective housing and infrastructure delivery. Adeloye (2008) submits that there is a lack of properly structured recruitment and training scheme for the construction workmen and the system of remunerating them is not attractive to new entrants. There is therefore an urgent need to address the workforce challenges in the nation’s construction industry. Olaoye (2007) asserts that the training and supply mechanisms for construction workmen are largely underperforming. Therefore, the objective of this study is to collect and synthesise relevant data on the construction workforce challenges in South Western Nigeria in order to develop a strategic model for resolving the identified challenges.

2. Workforce Shortages in the Construction Sector

- Sanni and Alabi (2008) argue that persistent neglect of the artisan training system by government has led to drastic fall in enrolment of new intakes into building trades. Consequently, it created a gap between demand and supply of construction workmen. This gap became wider with increased investment in shelter provision especially by individuals and families due to fast rising housing rents caused by pressure for accommodation especially in the urban centres (Agbola, 2005). Dainty, Root and Ison, (2004) contend that employers’ indifference to investment in artisan training negatively impacts the supply of the required workforce for construction work. In Nigeria, employers’ participation in artisan training is almost nonexistent, which further widens the gap between demand and supply of skilled artisans. The fallout of this is manifest in the difficulties faced by developers in sourcing suitably qualified and experienced artisans for house construction projects. Adeloye, (2008) laments that there is lack of trained artisans in the country, and that there is an urgent need to sort out a unified building construction training scheme that trains artisans and rewards those skills appropriately. Nworah, (2008) reports that there is an upsurge of migrant artisans and craftsmen from Togo, Benin Republic and Ghana in the recent time to Nigeria attracted by building contracting firms to fill the gap created by shortages in artisans trained locally.

3. Methodology

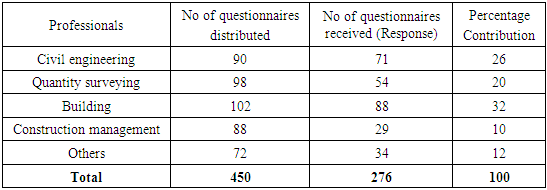

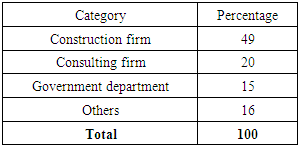

- Questionnaire survey, a quantitative research technique was adopted for this research. This was complimented with a thorough review of extant literature. Simple random sampling technique was employed in the questionnaire administration. South Western Nigeria is characteristically divided into three major sections namely Lagos-Ogun; Oyo-Osun and Ondo-Ekiti sections. Each of the three sections is homogeneous. For proper representation, the study focuses on three states; one from each section of the zone is included for analysis. A five-point Likert scale was used for the study and multiple target groups of key stakeholders were adopted for the purpose of obtaining a robust data that would provide a comprehensive understanding of the problem which would aid in the development of appropriate model for mitigating the challenge.Fellows and Liu (2015) posit that random sampling technique is a pragmatic way of collecting research data and it also ensures that the sample provides a fair representation of the population. In the event of the non-availability of the databases of the target groups in the study area as it is for this study, Leedy and Ormrod (2019) suggest a basic rule for determining a sufficient sample from a population as “the larger the sample, the better”. More specific guidelines were provided by Gay et al. (2009); Leedy and Ormrod (2019) for obtaining a sufficient and representative sample from a population while employing simple random sampling technique using N to represent the population and Where N= about 5000 or more, the sample size of 400 is adequate, the population size notwithstanding (Leedy & Ormrod, 2019). 450 questionnaires were distributed to employers and professionals. The employers included building contractors, government departments and institutions. While the professionals included architects, civil engineers, quantity surveyors, builders and construction managers in South Western Nigeria.

4. Results and Discussion

- Table 1 indicates the responses of the professionals. Builders have 32%, they are followed by civil engineers with 26%, then the quantity surveyors which have 20%, and lastly the others with 12%. The lowest response is from construction managers (10%).

|

|

5. Summary of the Main Research Findings

- The key research findings are discussed under appropriate subheadings as follows:• Training ModelsFindings indicate that two models are adopted in the study area, the college-based model and the traditional apprenticeship (informal training) model. While the informal model involves an on-the job learning approach with the master artisans as the key trainer, offering training to apprentices usually under an informal contractual arrangement for a period of three to four years. The college-based model operates normal school style with theories in classes and practicals in workshops; three terms in a session sand witched with short breaks.• Policy IssuesFindings indicate that education policy framework is inadequate with regards to recognition of prior learning achievements and provision for lifelong learning for people in vocational learning pathway. There exist a dichotomy between the general education and vocational education / training pathways; making the latter to become a dead end and repulsive for people to toll. This is one of the crucial factors that negatively impact artisan training. It was found that there is an awkward philosophy of vocational education as learning option for the less endowed and meant for the children of the economically disadvantaged. It was found also that government employment policies discriminate against vocational graduates giving preference to general education certificates over vocational equivalent in remunerations and appointments.• Regulation and coordinationFindings indicate that artisan training is largely uncoordinated and lacks proper government regulation and interventions; this is partly attributable to operation inefficiencies of NBTE. Programme accreditations in many technical colleges have been long overdue and the standard of training has fallen below the acceptable benchmark. This might be due to too large scope of operation of the NBTE as it is responsible for all polytechnics, monotechnics and technical colleges. Consequently, the policy framework establishing NBTE is due for reform. Findings indicate that there is no any government agency responsible for the regulation and coordination of the traditional apprenticeship training; no standardised training curriculum, assessment and certification process.• FundingIt was found that funding for artisan training is grossly inadequate; annual budgetary allocation for vocational education is not fair as compared with the general education. Little on nothing is provided for infrastructure and training facilities. There is limited funding for scholarships to attract trainees and other sources apart from government is virtually none existing.• RecruitmentFindings indicate that recruitment efforts are weak and ineffective and consequently, enrolment remains far below the carrying capacities of most of the technical training colleges. • Employers’ participation in trainingIt was found that there is poor participation of employers in the training; this is attributable to lack of incentives from government to motivate the employers. The situation is exacerbated by the absence of an appropriate public institution like the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) to drive the training in the construction industry and encourage industry engagement in training.

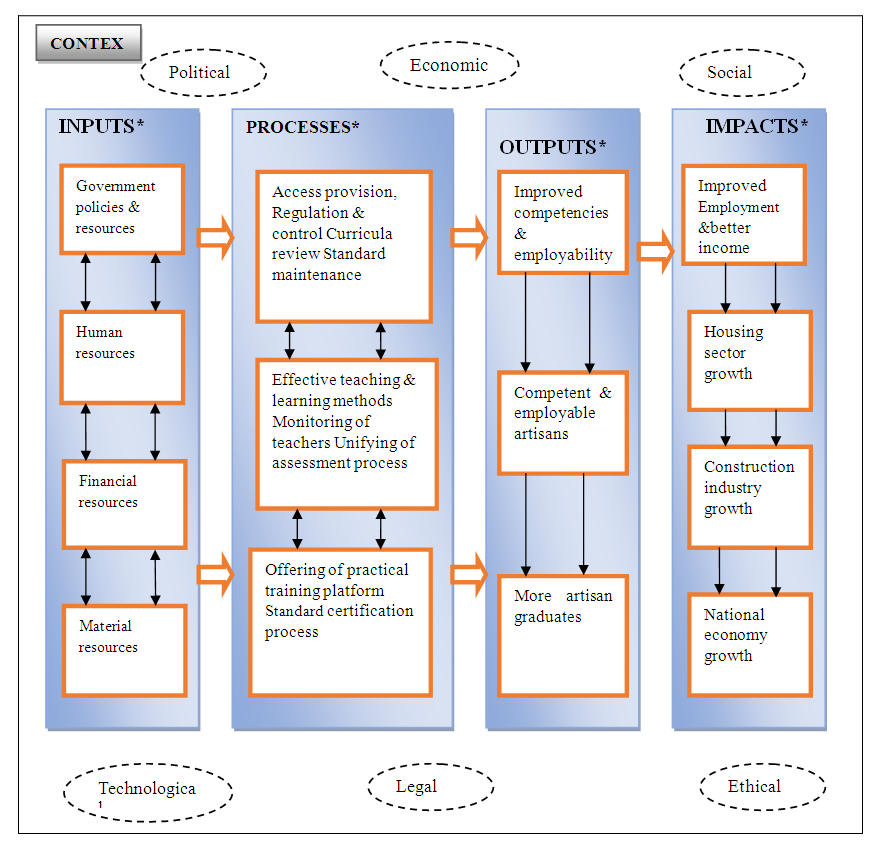

6. The Proposed Model

- Global evidence indicates that systems improvement is actualised and sustained through integrated approach by combining specific measures and processes. One of the objectives of this study was to develop strategies that would incorporate best practices for improving the artisan training system in South Western Nigeria. The proposed model is termed the Artisan Training Model, which is a system that identifies critical aspects of artisan training and allocates essential tasks and measures to key the stakeholders in the system in order to achieve the desired outputs and impacts. The IPO model of a general education system provides the clues for the development of the artisan training model.The Basis for the Artisan Training ModelThe model of a general education system provides the background and clues for the development of the artisan training model. According to Scheerens (2011), the model of a general education system captures education as a productive system whereby inputs are transformed into outputs. The model of a general education system provides the basis for understanding the artisan training system (European Commission, 2006; CEDEFOP, 2008b; Onwuakpa and Anyanwu, 2009; Necesito et al., 2010; Scheerens, 2011; UNESCO, 2011). The proposed model for the artisan training system in Nigeria in this research took clues from the model of a general education system as well as further review of literature and measures obtained from empirical findings.The Motivation for the Artisan Training ModelGiven the Nigeria population of over 180 million (World Bank, 2018) and an estimated growth rate of 3.2% (NPC, 2006) consequently, Nigeria has an enormous housing and infrastructure deficit.. The current situation in the house construction sector reveals that there is an acute shortage of house construction artisans both quantitatively and qualitatively. The shortage is a result of the poor performance of the artisan training system. The poor performance of the artisan training system has constrained the productive capacity of the sector and exacerbated the nation’s housing problem. Past policies have largely failed to address the realities of the skills crisis. The skill challenge is caused by a weak and neglected traditional apprenticeship and a poorly developed vocational college systems. Insufficient research efforts directed towards skills concerns, non-participation of employers in training, lack of recruitment strategies and a faulty and rigid National Qualification Framework have negatively impacted on the artisan training system. The current practice of outsourcing house construction artisans from neighbouring countries, for instance, Benin Republic, is completely unacceptable. This situation continues to exacerbate the unemployment rate in Nigeria which has moved from 12.3% in 2006 to 23.9% in 2013 and to 24.8% in 2019 (World Economic Outlook, 2013 & 2019). Articulating an appropriate blueprint to mitigate the poor performance of the artisan training system in the Nigerian construction sector is a serious challenge that necessitates critical attention and urgent responses. Artisan Training Best PracticesThe development of research instruments for this study was based on improvement measures and artisan training best practices across the world identified from the reviewed literature. A best practice is a technique or approach that has consistently shown successful results. It could also mean a strategy or technique that has shown through experience to deliver desired results (Measham et al., 2007). Clues were taken from the UK, the USA, Germany, New Zealand, Malaysia, and South Africa. The findings of this study have identified salient factors that have had a huge impact on the artisan training system in South Western Nigeria. The findings also indicated that there is room for significant improvement with respect to integration, industry participation, funding, employability, recruitment and policy interventions. The key message suggests that building synergies among key stakeholders and adopting best practices in training can achieve lasting improvement of the artisan training system. The prime goal of this study is underpinned by the need to investigate the dynamics that have seemingly impacted on the poor performance of artisan training system in the South Western Nigeria. The model is therefore introduced to accommodate the various argument and components in order to meet the objectives of the research. The Artisan Training Model is an enabler to mitigate the challenge of inadequate artisan training.The construction of the modelA graphical logic model illustrates the pathway or roadmap by depicting the steps to be followed in order reach a specified destination or achieve the desired change. A model specifies the connection between systems inputs and activities with the systems outputs and impacts. It also harnesses stakeholders to articulate strategies and approaches that would facilitate the realisation of the stated goal for the system (Taylor-Powell and Henert, 2008). The model serves as a point of reference and a unifying language for the participants in the system. The vision or the goal of a model must be clearly stated. The goal of a model refers to the motivation for it; the problem that the model stands to address. The goal of the proposed model in this study has been clearly outlined under the motivation for the artisan training model. The construction process follows the sound principles of logic. This suggests a reasonable arrangement of elements, and the interdependence between them in order to perform a specific task. The construction is usually done with the use of graphics or schematics (Taylor-Powell and Henert, 2008). Provision is made for the clear indication of the relationships among the components of the system. That is, the indication of how the procedures and activities in the system connect and the path that leads to the accomplishment of the goal. It also includes the measures that would help to check whether the system is meeting its set goals. In the construction process of the proposed model, clues were taken from the IPO model of a general education. However, some modifications were made in the proposed model. These modifications and the rationale behind them are discussed in the next sections.Context: The contextual factors in the proposed model are enclosed in dotted circles and positioned around all other elements of the system. This is done for the purpose of clarity and to show at a glance what exactly the contextual factors are and to inform the readers that they are impacting upon all the other elements of the system namely inputs, processes, outputs and impacts. Inputs: This assembles the resource inputs that go into the system; human, financial, material and policies. Upward and downward arrows are introduced to the proposed model to show the interconnectivity among the sub-components within the input component. Each of the sub-components cannot work in isolation but rather in collaboration with one another. The inputs component links with the processes.Processes: This captures the series of value-adding activities that take place between the resource inputs that transform into results of the system in terms of outputs and impacts. In the proposed model, the processes allocate prescribed solution-oriented activities suggested from the findings of the study to stakeholders in the system. These include for instance, the government role of widening access and providing improved funding; employers’ role of offering training platforms for artisans and that of training providers which include balancing of theory with practicals in the training process. A number of other activities and measures are brought under this component in the proposed model from the results of the study for the purpose of resolving the artisan training challenges. Product: In the proposed model, the product component encompasses short term results of the system, while the long term results are captured in a newly introduced separate component (impacts) discussed below. The downward arrows are introduced to link the sub-components within products component. The reason for the introduction of the downward arrows is to show the logical relationship between the sub-components as one leads to the other. For instance, the immediate results of adequate artisan training will lead to improved skills and competencies. These would in turn lead to production of competent and employable artisans from the system. With this kind of training offered by all the training providers, the result would be a greater number of capable artisans coming out of the system and becoming available to service the industry.Impact: This is an additional component introduced to the proposed model for the long term results of the system. The main purpose of its introduction is to clearly differentiate between the outputs component as short term results and the impacts component as long term results of the artisan training system. The long term effects of adequate training of artisans are beyond those outlined under outputs components. These have broader implications on the construction industry, the general employment outlook and the national economy at large. With more competent and employable artisans produced from the system, more citizens are empowered through skills acquisition. This would reduce unemployment and provide better income. It will also lead to increased outputs of the construction industry and ultimately aid the growth of the national economy. The downward arrows are introduced to depict the logical relationship between the sub-components within the impacts component.The details of the artisan training modelThe artisan training model provides an integrated approach to improving artisan training performance in Nigeria as well as assessing the current performance standard against the benchmarks or best practice criteria. Taking clues from the model of a general education system, the proposed model is based on guidelines, global best practice, standards and the findings of the study. The artisan training model seeks to maximise the goal of the strategies which is to improve the artisan training system in Nigeria through driving effective synergies among major stakeholders in the system; reforming key policies; reviewing priorities; reassessing roles; reallocating resources and building stronger collaboration across traditional boundaries to pursue common goals of an improved and sustained artisan training system. The model requires all stakeholders to have in place a number of training improvement activities or measures within their improvement plans. The model is an enabler of the strategies as it helps to identify and prioritise roles and specific areas in need of improvement. The proposed model for improving the artisan training system in Nigeria is shown in Figure 1 below.

| Figure 1. The Proposed Artisan Training Model |

7. How to Apply the Model

- The model describes the relationship between the various components of the artisan training system based on the IPO model of a general education. This approach employs best practices identified from the study and when adopted it would be capable of transforming the current position of the artisan training system to an attractive training system with a high degree of relevance to the needs of construction labour market. The model shows how the current artisan training could be improved. The present approaches and practices of handling the artisan training must change. To achieve success in this area, the leadership at the national level must subscribe to the change process. This has to start by a way of adopting a change in the philosophy of vocational education and training. This must be followed with the creation of enabling environment. Context (Enabling environment): There is a need for ethical politics and values as well as the political will in the leadership to lay appropriate emphasis on vocational education and training among the youth. As argued by Oketch (2007) vocational education is designed to develop the skills for entry into the world-of-work. It is therefore essential that this philosophy be fully understood and entrenched into the policies and programmes of the political leadership in Nigeria. The discrimination against vocational qualifications must stop while the basic infrastructure such as electricity and internet services need to be made available in order to facilitate the realisation of the vision. Inputs: This concerns the identification of the various stakeholders and the resources that they should harness for the artisan training system. These stakeholders include government, training providers, employers, parents and trainees. Building effective synergies between the stakeholders in the artisan training system is very essential to realising the desired change in the system. On the part of government there should be adequate policies reforms on artisan training, sufficient financial allocation, infrastructure provision and provision of adequate training facilities. The involvement of the industry partners in the design and delivery of training, especially in the provision of training platforms for industrial exposure is vital to avoiding skills mismatch. On the part of training providers, there should be in place qualified teachers, capable management team, experienced master artisans, balanced curricula and adequate textbooks. While the parents would have to provide moral and financial support and the trainees themselves would need to demonstrate commitment to learning and dedication of adequate time to study and skills acquisition.Processes: This component concerns the value-adding procedures, measures and activities of different stakeholders in the artisan training model and how the activities are inter-related to each other. This ensures that non-productive activities identified through the study are not repeated and are replaced with productive and value adding measures. For instance, regular review of training curricula; accreditation of master artisans before engaging in training; and sponsoring of media campaigns to attract young people to training. The model provides a reference point for all the role players in the training system to ensure success.Products: The products component of the model concerns the identification of specific results of the artisan training system arising from the interaction between the inputs and the processes on a short-term perspective. This includes improved knowledge, skills and ability; better competencies; improved employability and more artisan graduates. The model serves as a measuring instrument to monitor the performance of the artisan training system. The list of results expected on a short-term range would serve as the performance indicators at the product stage for the system.Impact: The impact component captures the long-term results of the interplay between input resources, value-adding measures in the processes component and the outputs. It describes the socio-economic returns of the training as they impact on the labour market, unemployment, poverty, the construction industry and the national economy at large. The model would provide a means of measuring the performance of the artisan training system at the impact stage through the use of the indicators. The indicators under the impact component include increased employment in construction, rise in income level of construction artisans, construction industry growth, reduction in poverty and growth in the national economy.

8. Conclusions

- The primary concern of this study is to collate and analyse relevant data on the shortages of construction workforce in order to develop a strategic model for mitigating the challenge in Nigerian construction sector. The study has revealed a complex array of factors responsible for the shortages. Clearly, there is a crucial need for an intervention in order to forestall aggravation of the situation and to make proper provision for future workforce demand. In response to the complex nature of the problem, this study has developed a strategic model that offers a holistic approach for resolving the matter. The focal point of the model is enabling synergies between key stakeholders in the industry. These synergies would go beyond traditional boundaries. The strategic model is supported up with a well articulated implementation plan. Evidently, it is hoped that the construction workforce challenge could be addressed. This is largely dependent on the timely appropriation and implementation of the model proposed in this study. This would help to mitigate the problem and reasonably improve the workforce situation in the nation’s construction sector.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML