-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2020; 9(2): 63-80

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20200902.03

Barriers of the Recognition of Informal Construction Workers towards Improving Their Skills; The Case of Recognizing Prior Learning (RPL) Programme in Tanzania

Upendo P. Mbunda, Didas S. Lello, Dennis N. G. A. K. Tesha

School of Architecture Construction Economics and Management (SACEM), Department of Building Economics, ARDHI University (ARU), Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania

Correspondence to: Dennis N. G. A. K. Tesha, School of Architecture Construction Economics and Management (SACEM), Department of Building Economics, ARDHI University (ARU), Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The study aimed at assessing the barriers of recognition of informal construction workers through RPL programme towards skills development; specifically, by identifying the stumbling blocks on recognition of informal construction workers in the rules and procedures of RPL programme; examining barriers towards skills development of informal construction workers to be recognized under the RPL programme, and proposing strategies towards improving the recognition of informal construction workers, through RPL programme. This descriptive research strategy used both qualitative and quantitative approach. Its research design based on random sampling techniques and the questionnaire survey. The targeted population sample included 68 randomly selected informal construction workers, drawn from currently enrolled candidates under the RPL programme, and is subdivided into two occupations by stratified sampling techniques i.e. Masonry/Bricklaying (MB) and Carpentry/Joinery (CJ), out of which 46 (68%), responses were obtained. Based on the ranking of factors with Relative Importance Index (RII), the study revealed the general barriers of recognition of informal construction workers, which included; worker’s perception of wastage of time, unstructured cooperation with private sector, poor knowledge of benefits of RPL certificates, lack of RPL awareness, and lack of adequate VETA centres. It concludes that; the awareness of the RPL programme is not well established; qualification standards (class standards) set, do not match the occupational standards (field standards) acquired by workers; complex process; and minimum age requirement being too high. The study recommends that; general awareness and recognition processes should be improved; information about the portfolio evidence for works which are not specified in the module should be clear, and generated to reduce the time and expenses during the enrolment; knowledge about the benefits of RPL certificates should be provided; VETA should help the workers to find a job through a dual apprenticeship program; have national target for number of informal construction workers to access recognition opportunities; contractors should use informal construction workers with RPL certificates; promotion of knowledge management and sharing; and an increase in VETA centres, especially in rural areas, must be done.

Keywords: Informal Construction Workers, Skills, Recognition, Prior Learning, Programme, Tanzania

Cite this paper: Upendo P. Mbunda, Didas S. Lello, Dennis N. G. A. K. Tesha, Barriers of the Recognition of Informal Construction Workers towards Improving Their Skills; The Case of Recognizing Prior Learning (RPL) Programme in Tanzania, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 9 No. 2, 2020, pp. 63-80. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20200902.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

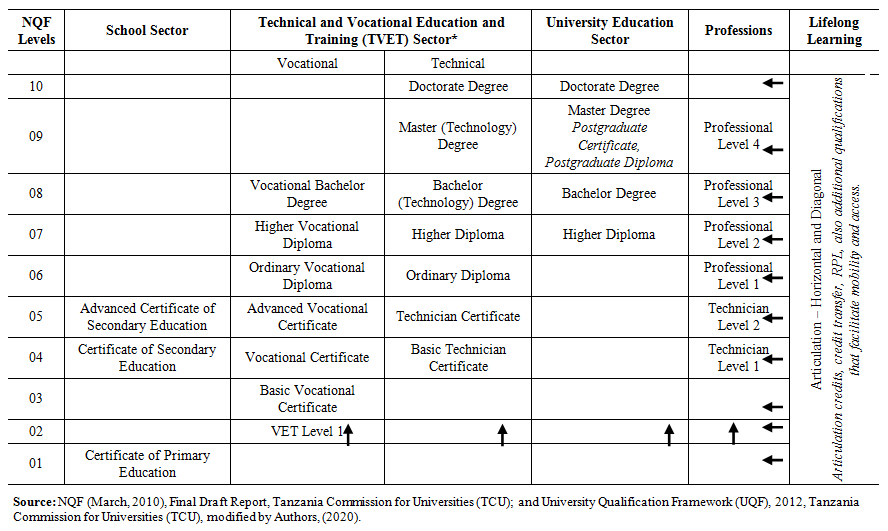

- The term informal construction sector, is used as reference to employment situation, with little or no regulation and protection, to informal construction sector workers and their jobs. In recent decades, it has gained popularity in developing countries such as South Africa, Nepal, India, Kenya and Tanzania [21]. Basically, the urban informal sector, apart from being the main source of job growth in most countries in Africa, it employs 66% of the labour force, which is the largest workforce, that contributes 60% of the Tanzanian economy [36]. Moreover, the Tanzania’s construction sector has been experiencing unprecedented growth, caused by; an increase in government budget allocation to infrastructure development; the increase in private investment in real estate and cement production; as well as an increase or growth on informality in construction activities attributed by; failure in land delivery systems and rapid urbanization the leads to informal settlements, informal construction system, informal labour and employees not directly protected by labour laws, and informal sector enterprises [17]. Furthermore, [17,18,21,22] assert that; the informal construction sector in Tanzania comprises of; large number of unorganized, unregistered and unregulated contractors, whom mostly are trained informally and paid low salaries; high rates of accidents; unprotected individuals and small enterprises that supply labour and contribute in various other ways to the output of the construction sector. Besides, the construction industry faces serious challenges related to its workforce, which includes; lack of proper training as well as limited technical vocational and managerial skills to informal construction workers, employability and skill mismatch (skill paradox) [1].All these issues can be solved if they are formalised, trained, registered and regulated, given the fact that; construction is one of the primary provider of work in urban areas [22]. Several initiatives have been taken to address these concerns, though still facing barriers, to support the solution. [8] asserts that; Tanzania’s Vocational Education and Training Authority (VETA), through the project of social dialogue process, developed a programme of formalizing informal construction workers, where informalities on skills are formalized in order to improve the quality of informal construction workers and their product in the construction industry. This was achieved by; Tanzania initiating a Recognition Prior Learning (RPL) programme, as a result of a 2010 research, on ensuring the formalization and upgrading of informal construction workers. RPL, is basically a process of assessing and certifying, the skills and knowledge of a person, in order to meet standards of the formal construction industry. [16,26] have also defined it as a process of evaluation of those skills and knowledge acquired through life experience, allowing them to be formally recognized by the qualification systems. It is a central aspect of lifelong learning.The standards to be met are as specified in the National Qualification Frameworks(NQF), which is a national instrument for development and classification of qualification, according to a set of criteria level of learning and skills.

| Table 1.1. National Qualification Framework (NQF) and associated qualification titles |

1.1. Problem Statement

- In many developing countries like Tanzania, construction works or activities make use of three main resources, i.e. materials, equipment and/or plant and labour (e.g. informal construction workers), which engage a variety of skills ranging from specialized professionals to operatives, who translate drawings into a physical object i.e. a building, a roads etc. at a define duality and quantity [10], with informal construction workers making a good contribution. The contribution of informal workers has been growing at a higher rate, due to the increase in demand for public and private development; and these workers are highly important in the construction industry, because it is a labourer oriented industry due its nature of works [10], and it affects a number of expectations, and quality of works [8]. Despite the growth of informal workers, who basically have varying informality skills [10], their balance against formal workers must be established, so as to suppress the problems of informality in the economy. Thus, basing on this view, the Government of United Republic of Tanzania, through VETA, which is a self-governing government agency, decided to formalize the informal construction workers under RPL programme, in order to achieve the balance in the construction industry. But, still, the RPL programme output has not been highly achieved, as per the expectation, due to the fact that; the number of informal construction workers formalized per year, is small compared to the approximate number of informal workers joining the industry each year [11]. Hence, this study focuses on assessing the barriers on recognition of informal construction workers through RPL programme towards skills development; specifically, by identifying the stumbling blocks on recognition of informal construction workers in the rules and procedures of RPL programme; examining barriers towards skills development of informal construction workers to be recognized under the RPL programme, and proposing strategies towards improving the recognition of informal construction workers, through RPL programme.

2. Literature Review

- Apart from being used for academic references; the study findings are vital in proving awareness on the objective itself, and an overview from workers of the rules and procedure for eligibility to be recognized through RPL programme. Also, its knowledge is significant to the government on recognizing strategies that may be employed, in order to improve the programme under VETA, while proceeding to add other occupations under the programme. The ultimate goal, is to improve the existing framework, towards improving trade skills for informal construction workers. The study covered the informal construction workers working on Masonry/Bricklaying (MB) and Carpentry/Joinery (CJ), located in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania. MB and CJ are the only occupations/ trades related to construction industry, covered by the programme currently, and it is anticipated that; success of these selected trades, will establish a base for future expansion of other building trades. The study was conducted in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania, due to availability of a large and reasonable number of construction projects; informal construction workers; as well as Dar-Es-Salaam being the first region to host the programme.

2.1. Construction Industry in Tanzania

- Construction industry in Tanzania as per [5, 6, 17, 25,]; is an economic investment which includes real estate, transport, infrastructure, and other civil works such as water supply. The industry comprises of the regulated and unregulated parts, termed as a formal and informal sectors. This informal sector plays a large role on labourer provisions since the industry is labour intensive industry; whereas the sector as grown in size contributing between 60% - 80% of employment opportunity and to the economy.

2.2. Informal Sector

- The term informal sector is defined basing on the employment situation, and on economic enterprises. Basing on employment situation; the informal sector is used on describing employment or livelihood generation, within the developing country. Meanwhile, basing on economic enterprises; the informal sector is defined as small enterprises, which are not registered according to national, and local government regulation; while operating with little capital, using mostly local resources, simple technology and buying and selling in an unregulated and competitive market. [19] asserts that; in the construction industry, the term informal sector, refers to not only unprotected and unregulated individual and enterprises engaged in construction activities, but also informality of contract between building owners, and workers, as some building in the informal system, may have planning permission.

2.3. Informal Construction Workers

- Writing by [17,22], enlighten that; informal construction workers in the Tanzania context, are any individuals or groups who are not registered, or officially recognized by the government, characteristically unprotected and unregulated with no formal contracts working on verbal agreements. Moreover, they assert that; the mode of payment of the informal construction workers is mostly on basis of piecework, their social securities are minimum, with no legal framework, and sometimes no health benefits/facilities provided under given assignment or formal contract of employment. In this system, building owners procures materials and hire them to construct, or repair the whole or part of the building. They are cheaper, hence helping the construction firms, in cutting down the cost, given the fact that; most of the construction works is seasonal, and keeping workers on a permanent basis when there are no works is costful. According to [22], informal construction workers, move around to active construction sites, and are hired by the owner or gang leaders (foremen) in charge of the construction on casual basis. Employment on a particular site may last from one day to one month or more depending on the amount of work, availability of material and funding. In some cases, work stalls and the workers have to move around different construction sites with anticipation of getting a job as they wait for activity to start again on the previous site. Moreover, [17] expounds that; in most cases, they informally acquire skills through imitating from their family and friends, and they do not acquire official recognition to enable them to proceed with formal education from higher institution learning, to secure jobs and be regulated by national and local government regulation with full protection from employment and labour related Acts.

2.4. VETA and the RPL Programme

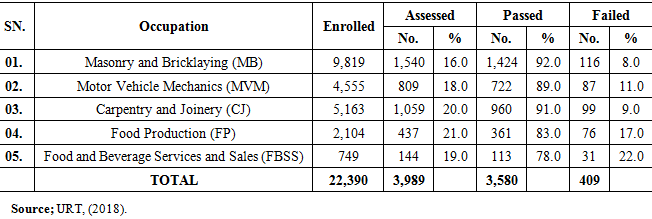

- The Vocational Education and Training Authority (VETA1) is an autonomous government agency established an Act of Parliament in 1994 (Cap 82 revised edition 2016) with its function as specified in section 4 (1) of the Act. Its main objective is to oversee The Vocational Education and Training system in Tanzania by coordinating, regulating, financing and providing of Vocational Education and Training in Tanzania. VETA, focuses on improvement of the VET system in order to support national social economic development through improvement of equitable access to VET, quality VET provision, employability of VET graduates, and enhancement of VET management capacity and financing. Skills development has been a major policy agenda in several countries and there is a lot of emphasis on the promotion of vocational education and training (VET) programs [1], due to the fact that driving a national economy depends on sufficient and skilled labors, and skilled labors are improved through the training of vocational-skills, [35]. [20], asserts that; in the improvement of quality and access to VET, VETA has taken various efforts including the establishment of Regional Vocation Training and Service Centres (RVTSC), Kipawa ICT, VETA Hostel and tourism training institution and district vocational training centres (DVTC). In Dar-Es-Salaam for example, these efforts enable an increased enrolment of trainees from 77,051 in 2005 to 189,687 in 2017 but there were limited chances in VET centres to meet the increased demand. It can be noted that; only a few were assessed and certified as depicted in Table 2.1 below. Moreover, in establishing itself firmly, VETA decided to establish various programmes to increase access so as to meet growing demand. These programmes were; a) Dual apprenticeship, b) Skills Enhancement Program (SEP), c) Integrated Training for Entrepreneurship Promotion (INTEP), and d) Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL).Dual apprenticeship programme is a training system at workplace running with collaboration with industries through an exchange of students between training centre and industries. It was initiated to help youths to easily get employment through vocational training at a workplace, whereas occupations involved are motor vehicles, electronics and hotel management. The need to incorporate other trades such as Carpentry and Masonry is necessary. Skills Enhancement Program (SEP), provide training to employees from different companies by updating and upgrading skills due to change in technology. Integrated Training for Entrepreneurship Promotion (INTEP), is an employment-oriented program which focuses on training people who are unemployed, underemployed and those who are working in the informal sector.RPL is the only programme for assessment and recognition of skills acquired informally at the workplace, whereby skills are assessed, the gaps are identified, and training programme is organized to fill the gaps, [20]. The first research conducted in 2010 by VETA for initial initiation processes of the RPL programme, managed to establish standard tools and guidelines to run the programme [11]. Two (2) occupations from the construction industry certified under RPL during the first phase of RPL, were Masonry/Bricklaying (MB) and Carpentry/Joinery (CJ). These research paper is therefore based on these two occupations. Other occupations were Motor Vehicle Mechanics (MVM), Food Preparation (FP) as well as Food, Beverage Services and Sales (FBSS). The second phase is yet to be rolled-out, and it includes; Electrical Installation (EL), Design Sewing and Clothing Technology (DSCT), Plumbing and Pipe Fitting (PPF), and Welding and Metal Fabrication (WF). From February, 2017 to November, 2018 with support from the Prime Minister’s Office(PMO), VETA managed to conduct a Recognition of Prior Learning Assessment to all regions of Tanzania mainland (A total of 3989 candidates were assessed). Details of this phase’ assessments are as indicated in Table 2.1, hereunder;VETA, is expecting to add new fields, after rolling out of the occupations mentioned under Table 2.1 below. In relation to construction industry, VETA is also planning to develop RPL assessment tools for Information Communication Technology (ICT), Refrigeration and Air Conditioning (RAC), Renewable Energy (RE).

|

2.5. Benefits of RPL

- RPL as the programme offers many benefits to both formal and informal groups of workers, employers, government, training agencies and society in general. Some of the benefits of the RPL programme as discussed by [7,11,29] includes;- For Individuals:- Gives opportunity to get formal education and training programmes which give them legal status for lifelong learning like joining in higher institution learning. § The workers get great access to job mobility and employment,§ It helps in the formalization of the economy and gives better job opportunity since workers acquire qualified professional,§ Eligibility or access to apply for government tenders and financial services for businesses, thus improving business potential,§ Improved security in operating environment through self-worth, confidence and respect,§ Improved technical and commercial in skills and knowledge as many individuals may require upgrading of their skills and knowledge in order to meet the standards,§ Duplication learning on what they already knew is minimized, hence RPL saves workers time and resources,§ It motivates students to continue with their studies,§ It improves worker’s confidence self-esteem and motivation to learn, and § It develops workers independent study skills through evidence gathering.For Employers:- Having qualified and certified workers, this helps any organization to meet the demand of its market in the competitive economy.§ RPL offers employers an opportunity to convert the investment they made in training programmes into credit for their employees,§ Workers with upgraded skills and knowledge would be more productive and innovative due to change in technology, and It improves worker’s self-esteem and promotes a positive learning culture,§ Employer’s cost of identifying training needs is reduced,§ The employer is easily determined if the employees need additional training, and § RPL simplify training needs to companies.For Educational Institutions;-§ It brings the opportunity of work and learning together,§ Its offer staff development within the institution, RPL requires professionals to act as teachers, facilitators, assessor and moderators,§ RPL can act as a marketing tool to educational institutions since many workers with informal skills and knowledge will be attracted and convinced to join the programme for recognition purpose,§ It brings together academic and VETA together, and § It attracts more experienced workers to higher education hence it providing flexible learning opportunities.For Society;-§ It promotes equity and social inclusion as it provides a second chance to disadvantaged persons (who are informally acquire their skills) to acquire formal qualifications.

2.6. Eligibility Condition for RPL

- Any informal workers with a minimum of 17 years are eligible for RPL, if and only if he/she has at least three years of training, or working experience in the relevant fields such as; masonry and bricklaying (MB) and carpentry and joinery(CJ). Some occupations require more years in work experience than others depending on the complexity of the competency of the tasks. VETA will provide specific entry requirement for each occupation [29]. Even if a candidate does not qualify or do not meet the minimum requirement, it is still beneficial to seek advice from RPL facilitator who can advise on how and what you need to do to qualify for RPL in future.

2.7. Quality Assurance

- This is a mechanism to ensure credibility, transparency and consistency in policy, legal and regulatory framework, institution framework for RPL, active engagement of employer and workers, RPL guidelines, development of standards and assessment tools and methods. It further safeguards portfolio evidence, credibility of RPL centres, training of facilitators, assessors and moderators, grading skills of candidates, moderation of assessment, RPL information, provision of skills upgrading, internal cooperation and research monitoring evaluation.

2.7.1. Assessment Tools and Methods

- VETA is responsible for the development and implementation of the RPL guidelines, tools and methods. These should meet formal and informal economy and VETA curricular to ensure quality in the PRL processes, and to avoid inferior consideration of certificates provided under the programme. According to [29], the assessment tools and methods should be; § Valid to assess the desired competencies to candidates,§ Reliable and consistent such that, if various assessors use the same assessment tools and methods should get the same results,§ Transparent on assessment tools, methods and standards to candidates, assessors and moderators,§ Equitable and flexible in term of time, place and method,§ Manageable and achievable in term of time and resources available and § Fair enough to allow for an appeal.

2.7.2. Portfolio of Evidence

- Where candidates are required to provide evidence, evidence gathering needs to comply with the rules of evidence [29], which are;§ Valid to covers key competencies of a qualification,§ Sufficient to allows for assessors to make decisions on the level of competency,§ Contemporary, and Real (candidates own work).The evidence in the portfolio, may consist some or more of the information as per the general guidelines [29]; job/work descriptions, skills logbooks, videos and/or photographs of work activities, formal statements of results and certificates sample of work produced, written testimonials from managers, owner, employers or worker’s associations or any other evidence that is valid, sufficient, authentic and current.

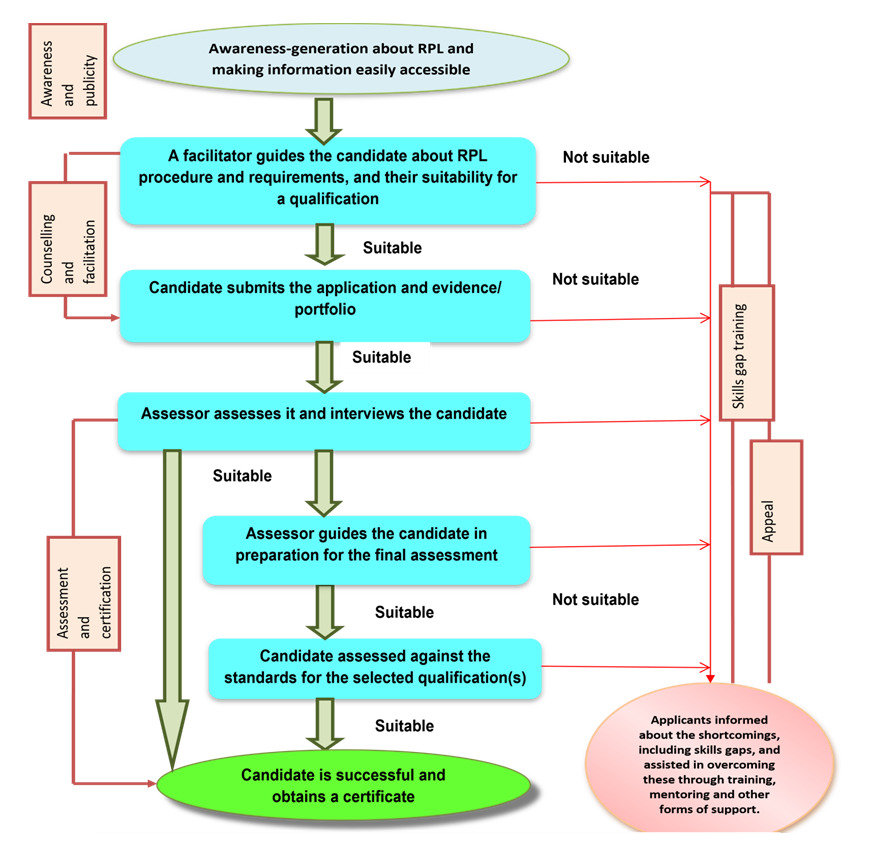

2.8. RPL Processes

- These are the processes for candidates to follow in order to be certified although these processes and organizations vary among the countries. The core of RPL involves two key processes which are counselling and facilitation and assessment and certification, but these key processes are supported by some mechanisms results to five(5) processes,a) Awareness Generation, b) Facilitation, c) Screening of an Application, d) Final Assessment, and e) Certification and Feedbacks.Henceforth, this study has also shed some light and concerns that hinder of influences the RPL processes.

2.8.1. Awareness Generation

- This is the process of publicity on the information about RPL to the potential candidates, employer and other stakeholders. Publicity and awareness are promoted by VETA using different models such as; websites, social networking, group information meetings conducted at workplaces and education institution, brochures, other publicity materials, and media. They publish information about what is RPL, what its benefits are, whom to contact, as well as the process, estimated costs, timeframe, eligibility requirements and assistance available.

2.8.2. Facilitation

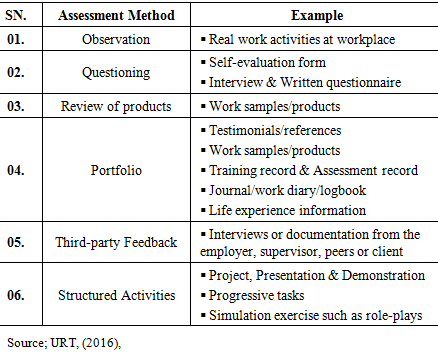

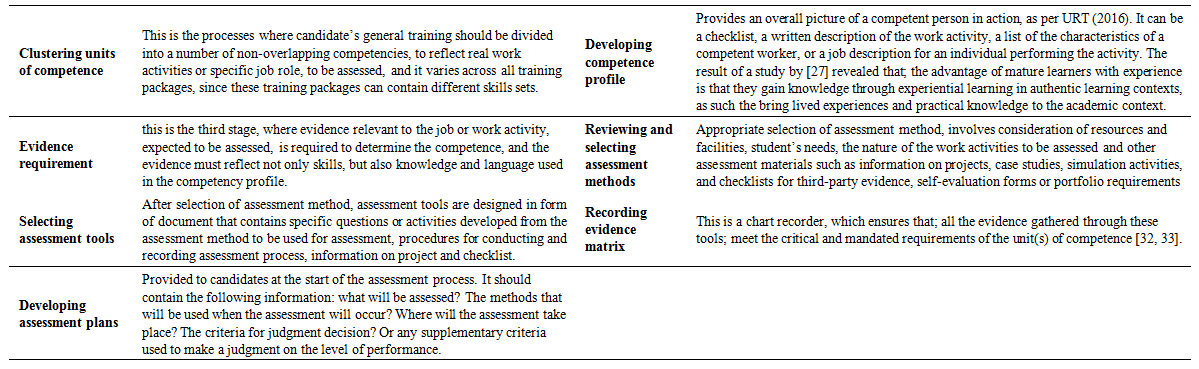

- This is sometimes referred to as counselling and facilitation, whereby in this processes, the candidates interested in the RPL, obtain detailed information and orientation from the facilitator at a VETA centres [2]. The facilitator is responsible for the initial assessment of the candidate’s eligibility and guides them in complete RPL procedures particularly on a collection of evidence, that helps a candidate in deciding for application and qualification to apply for RPL. The Candidates are provided with information such as; application form, competency standards for the occupations (modules of employable skills), eligibility condition for the occupations and nature of evidence required for the portfolio if the assessors use evidence that confirms the individual’s claims to recognize skills and competency. Forms of evidence appropriate for RPL are;a) Direct evidence which involves direct observation; oral questioning; and demonstration of specific skills, b) Indirect evidence which involves assessment of qualities of a final product; review of previous work undertaken; and written tests of underpinning knowledge, and c) Supplementary evidence which involves third party, such as testimonials from employers; reports from supervisors; work diary or logbook; and examples of reports or work documents.There are many assessment methods and techniques for gathering evidence [2]. Some of them are explained in Table 2.2 below;

|

| Table 2.3. The key stages adopted for the Recognizing Prior Learning (RPL) programme |

2.8.3. Screening Application

- This is the selection of candidates for final assessments. Firstly, candidates should submit the application form, and the prescribed fee to facilitator, at VETA Centre. Then the facilitator will send the application form, and evidence to the assessor in a specific occupation, to find out the suitability of the candidate for the applied occupation and units. Later, the candidate is called for an interview and clarifications. In case of satisfaction of portfolio, knowledge and experience of a candidate, he or she will be advised about the nature of final assessments, grading system and other relevant information, but if an assessor is not satisfied with the collected evidence then candidates will be required to collect additional evidence or upgrading skills in some area before applying.Grading of Skills of Candidates:- workers who have received training through a non-formal system are recognized into three grades under this programme;a) Grade A; 91% to 100%b) Grade B; 81% to 90% andc) Grade C; 75% to 80%.This means that; the lowest grade for candidates to be considered pass or successful, is 75%. Below that; a candidate is not considered successful, and they will not be legible for recognition.

2.8.4. Final Assessment and Feedbacks

- The final assessment is done to candidates, and the suitable time and place for assessment will be informed as summarized in a process shown in figure 2.1.

| Figure 2.1. The RPL programme flow chat, (Source; Adopted from by VETA, (2014).) |

2.8.5. Appeal Processes

- Refers to a process which allows candidates to challenge an assessment decision reported to them, as well as enabling them to be re-assessed. Candidates have to pay a reasonable non-refundable fee which discourages playful appeals, but it should not prohibit appeals altogether. The assessor should provide clearly time period for complaining and appeal (which is within thirty (30) days of the release of results), and a fair timeline for them to have complaints and appeals resolved.

2.9. Candidate’s Guide Towards RPL

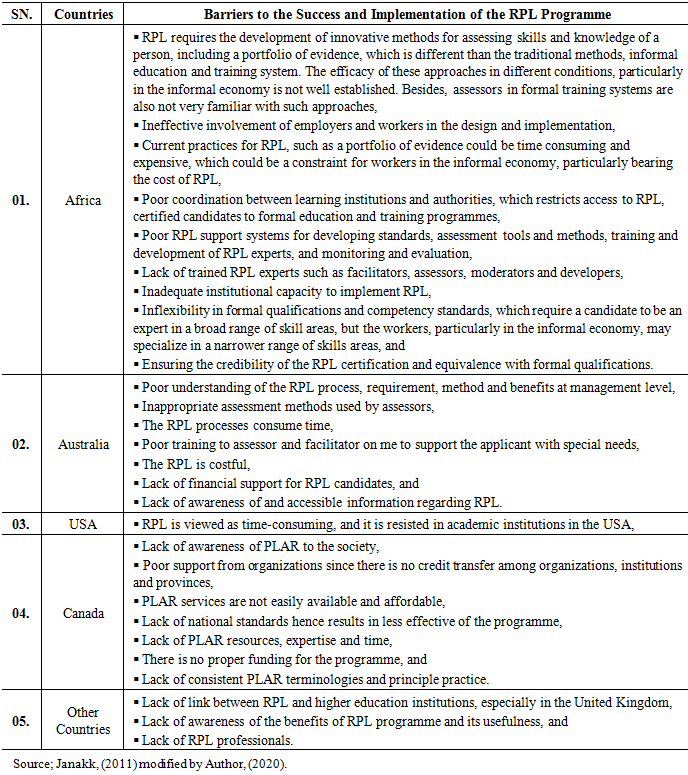

- This is the standard qualification document for RPL candidates only. Apart of RPL general guideline, VETA published another guideline for candidates only, which explains how candidates get skills and competencies recognized. It explains, a place where candidates obtains information about the programme, categories of evidence appropriate for RPL, what should a candidates do to get assessed?, how and what should be prepared by a candidates, steps to be followed, submission time for the application, cost involves, possible time for the RPL processes and advantages of certification. Before filling self-assessment form at VETA, candidates should identify which area of competency knowledge and skills which is suitable for him or her to apply for RPL. One of the steps in the process is to identify learner’s profile. This was ironed in a study by [27] which revealed that; having the learners profile helps to identify specific characteristic of RPL candidates in terms of personal attributes, learning context, knowledge and skills gained through a process of personal development, successful candidates who will be able to provide relevant evidence, confirmed by the third party as competent, and has performed to the required standards on RPL are awarded modular certificate. This gives a candidate respect among peers and customers and/or employees, provides opportunity to get decent employment in formal companies and/or organizations, gives access to contract bids according to his/her levels of competency. It also makes it easier to register a company and provides opportunity to be enrolled in formal trainings of their wish. Table 2.4 highlights general barriers viewed in various parts of the world. These are compared with specific barriers in Tanzania and discussed further in section 4.0.

|

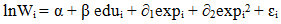

2.10. The Human Capital Econometric Model

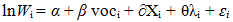

- [1] used the standard Mincer’s earnings/wage function, also known as the human capital earnings function, to estimate the returns. It can be expressed as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

3. Methodology

- In line with [12,13] writings; the methodology used in this designed descriptive research design study, was case study survey. Also, the study used both qualitative and quantitative approach, which made it easier in determining the intended objectives, samples and design of the study, as well as ranking the rules, procedures, barriers and strategies of recognition of informal construction workers through RPL programme.

3.1. Data Collection Methods

- Generally, both primary and secondary data collection, were done using multiple sources of evidence. Questionnaire survey was used to collect primary data from various certified and non-certified construction workers in Masonry/Bricklaying (MB) and Carpentry/Joinery (CJ) occupation trades, under the RPL programme, in which the respondents answered the questions on their own [9]. Some of the questions were close ended and others were open ended to the respondent to attest their own opinion, and give more information regarding barriers and challenges of the RPL programme. Furthermore, secondary data concerning the rules, procedures, barriers and strategies of recognition of informal construction workers through RPL programme, were collected from literature review via published and unpublished books, journals, newsletters, magazine papers, webpages, articles, papers, guidelines and related national qualification frameworks(NQFs). All respondents had different years of experience in the construction industry.The questionnaire was divided into four(04) parts; first part, inquired on general information about respondent; second part, canvassed information on rules and procedures which acted as barriers for informal construction workers to be recognized under VETA through RPL programme; third part, covered other barriers of informal construction workers to be recognized under VETA through RPL programme; and the fourth part, covered strategies on improving the recognition of informal construction workers under RPL programme. Closed-ended questions were used as they are very convenient for collecting factual data and are simpler to analyze because the range of potential answers is limited, [9]. The pilot study was carried out to mark better the quality of the questionnaire and improve reliability of the questions with the use of 5-point likert scale, the respondents were asked to respond to each statements, by indicating which statement is Most Relevant(SR) = 5; More Relevant(MR) = 4; Relevant(R) = 3; Less Relevant(LR) = 2; Not Relevant(NR) = 1, so as to identify rules and procedures, examine barriers and propose strategies of recognition of informal construction workers through RPL programme. This type of scale has been found to be acceptable in other construction management research.

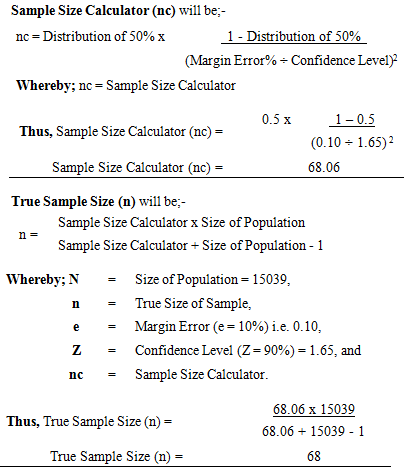

3.2. The Study Population and Sample Size

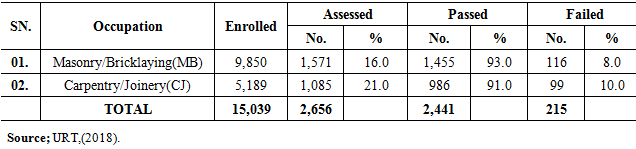

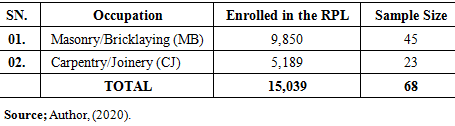

- The study sample population included certified and non-certified construction workers in Masonry/ Bricklaying (MB) and Carpentry/Joinery (CJ) occupations, under the RPL programme, in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania as shown in Table 3.1. The two filed were selected due to the fact that; they are the only trades, the were the first to be certified under the RPL programme.

|

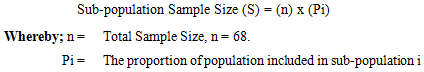

Henceforth, the total sample size for the study was 68 certified and non-certified construction workers in Masonry/Bricklaying (MB) and Carpentry/Joinery (CJ) occupations, under the RPL programme, in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania. Meanwhile, the population was divided into sub-population sample size (S), as depicted in Table 3.2 in which;

Henceforth, the total sample size for the study was 68 certified and non-certified construction workers in Masonry/Bricklaying (MB) and Carpentry/Joinery (CJ) occupations, under the RPL programme, in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania. Meanwhile, the population was divided into sub-population sample size (S), as depicted in Table 3.2 in which;

|

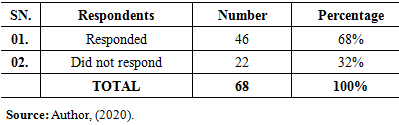

3.3. Respondent’s Response Rate

- The study targeted 68 respondents, whereby a total of 48 response from various construction workers who acquired their skills and knowledge informally were obtained, representing 68% of the response rate as seen in Table 3.3. This is the reliable responses rate for data analysis as per [3] who insists that; any response of 50% and above is adequate for analysis.

|

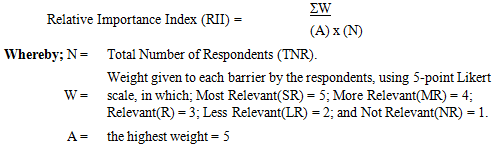

3.4. Data Processing and Analysis

- Both qualitative and quantitative data were analyzed, whereby qualitative data were examined and analyzed manually, through contents analysis, and categorized according to the way they relate to the research objectives and questions. Quantitative data were analyzed and computed by using SPSS, baes on the variables of the study. Relative Importance Index (RII) was then adopted to identify critical stumbling blocks, barriers and strategies for the improvement of the RPL programme, and then finally factors were ranked accordingly. The higher the value of RII, the more important was the barrier of recognition of informal construction workers.

4. Results, Analysis & Discussion

- Main parameters used for investigation in this study were to identify the stumbling blocks on recognition of informal construction workers with regards to the rules and procedures of RPL programme; examining barriers towards skills development of informal construction workers, and proposing strategies towards improving the recognition of informal construction workers, through RPL programme.

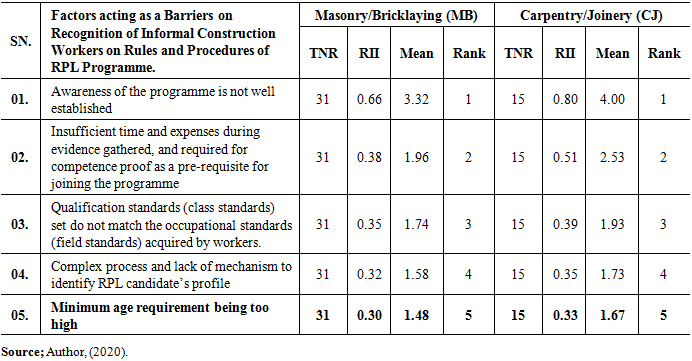

4.1. The Stumbling Blocks on Recognition of Informal Construction Workers in Rules and Procedures of RPL Programme

- This question, aimed at reviewing the rules and procedures for RLP processes, and to find out how these rules and procedures, affect the general recognition process of informal construction workers. The question based on the guidelines for RPL processes including a general guideline for RPLA, assessor’s guideline for RPL, guideline on how to get candidate’s skills and knowledge recognized, in order to review the rules and procedures for RPL processes, and found out its impacts on recognition process of informal construction workers who acquire their skills and knowledge informally. Basically, the study reviewed the following;Firstly, according to the guidelines for RPL programme, any informal construction worker is eligible for recognition, only if he/she has a minimum of 17 years, with 3 years of learning or working experience. The RPL programme, is assessing and certifying skills and knowledge regardless of how they have been acquired. This means that; about 15% of the informal construction workers out of 93.33% of the informal workers have been given a chance to be certified, since their education background is not considered, but also the age criteria set in the guideline is reasonable. It also allows workers with majority age according to the employment and labour relation Act.Secondly, the RPL programme is conducted in sequential processes which are; (a) awareness, (b) facilitation, (c) screening, (d) final assessment and (e) feedbacks and certification. This means that the programme is conducted in a logical order by starting with awareness generation through VETA website, fliers and through media and for those who are ready to join the programme gets more information about the whole RPL process to the facilitator. The eligible applicants are screened at first, to determine in which area, they are competent to be assessed and recognized, the workers are supposed to fill the assessment form with three Modules of Employable Skills (MES) and he/she is advised to gather evidence where necessary for the final assessment (test). Few months after test, the results are published and those who have passed, are awarded the certificate for recognition. What is not clear here is that, the certificate has not been equated to the existing NQF levels.Thirdly; for those applicants/informal workers found not eligible for the recognition, they are informed about the outcome of not being recognized, and the way to overcome it. This means that; even if an informal worker is found not to be eligible for the first time, he/she has another chance of being recognized after, either by learning a short course of his/her area he/she wishes to be competent at VETA, or back to the “street/vijiwe”, to get more experience for him/her to be reconsidered for certification.Fourthly; the gap/skills upgrading course, before certification of any applicant, VETA is providing skills upgrading course on theoretical coverage of specific field/module, crosscutting skills (life skills, sense of quality assurance and contract making), health and safety training, skills on the proper use of materials, tools and equipment. This means that; an informal worker acquires the formal theoretical knowledge, before their certification under the RPL programme.Lastly; appeal process for candidates who are not satisfied with the results, whereby the programme ensures fairness and transparency to its applicants and allow the candidates to be reassessed whenever he/she does not satisfy with the assessment decision. Apart from the processes, the study ventured on how the rules and procedures affect the enrolment or registration of candidates, hence acting as the barriers of recognition of informal construction workers from the rules and procedure of the RPL.Results from Table 4.1 show that; in the rules and procedures of RPL programme, two factors were revealed to act as critical barriers of recognition of informal construction workers on both MB and CJ occupation. The first factor was, awareness of the programme not being well established, ranking first with a RII of 0.66 and 0.80 for MB and CJ, respectively.

|

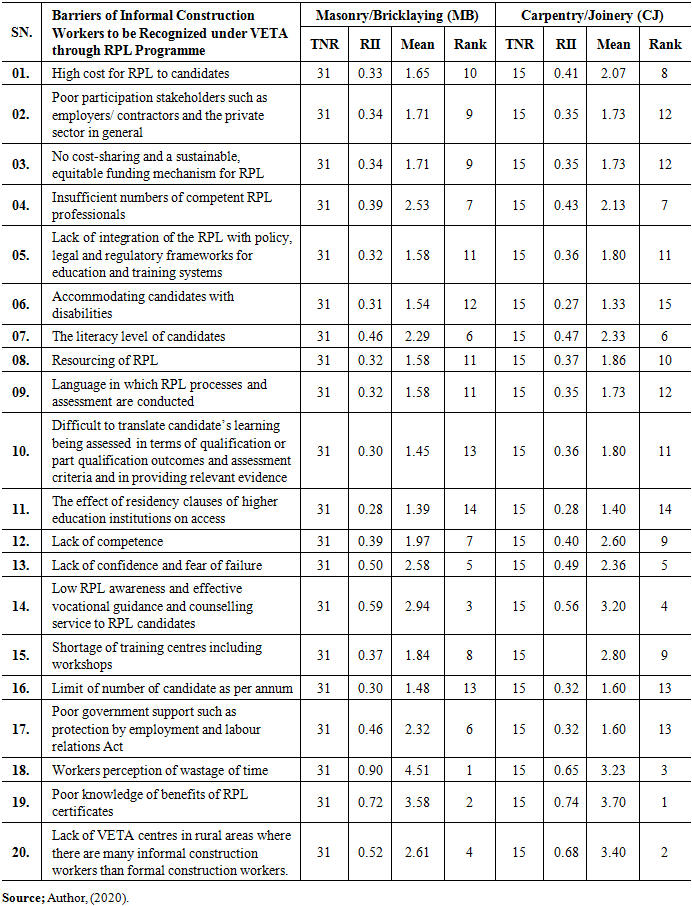

4.2. Barriers towards Skills Development to Informal Construction Workers to be Recognized under VETA through RPL Programme

- Findings as seen in Table 4.1, revealed four most critical barriers on recognizing informal construction workers in relation to skills development, determined from MB and CJ occupations. The critical barriers determined from MB occupation were; workers perception of wastage of time which was ranked first with RII of 0.90; poor knowledge of benefits of RPL certificates, which was ranked second with RII of 0.72; low RPL awareness and effective vocational guidance and counselling service to RPL candidates, ranked third with RII of 0.59; and lack of VETA centres in rural areas where there are many informal construction workers than formal construction workers which was ranked fourth with RII of 0.52. For the CJ occupation, the critical barriers included; poor knowledge of benefits of RPL certificates, which was ranked first with RII of 0.74; lack of VETA centres in rural areas where there are many informal construction workers than formal construction workers, which was ranked second with RII of 0.68; workers perception of wastage of time, which was ranked third with RII of 0.65; and low RPL awareness and effective vocational guidance and counselling services to RPL candidates, which was ranked fourth with RII of 0.56.Furthermore, more comments were made by respondents from MB and CJ in open-ended questions, on the four most critical barriers on recognizing informal construction workers in relation to skills, as follows§ Complex process and lack of mechanism to identify RPL candidate’s profile;- tracing candidates who have not undergone formal process, poses the need to understand specific characteristics of RPL candidates, thus requiring some sort of screening. Understanding candidates’ personal attributes, knowledge, skills gained informally during the process of personal development prior to admission to the RPL programme matters. This is because, they have different needs and responsibilities than students who have just completed formal education [27]. All respondents showed to have peculiar profile in their CV’s and have experienced different challenges.§ Workers perception of wastage of time;- 88% of the respondents claimed that; informal construction workers, decide not to enrol under the RPL programme because, they feel like it is a wastage their time in relation to their family responsibilities. This is in accordance with the study by [27] that established similar scenario, where participants had mentioned a variety of emotions because of dysfunctional relationship and context, reflecting negative experiences. Moreover, they availed that; sometimes when the announcements on the new phase of RPL programme enrolment are made, they found themselves having construction works/tenders to do, and they cannot sacrifice their works/tenders which is the source of their income/earning for the sake of certification, given the fact that they are the bread earners. Thus, the time for enrolment lapsed without most of them being registered for recognition. Additionally, some of the enrolled applicants failed to be assessed for recognition and certification because, during the time of assessment, they found themselves having the works/tender to do.§ Poor knowledge of benefits of RPL certificates;- 73% of the construction workers showed to believe that, a certificate is for life learning purpose only, and since they do not have dreams to continue with learning, they ignored the importance of being certified, while claiming that; their employment circulation is a self-employment, and there is very rare chance of meeting a client who wants a certified worker to do his/her job. In fact the PRL certificates awarded to these informal workers, give an equal chance as formal workers to proceed up to highest education level, since the National skills qualification frameworks (NQF) for vocation and technical education, the RPL certificate is considered an articulation for these informal workers to be awarded certificates of competence up to level III under VETA, where the VETA awarding system has been merged with that of the National Council for Technical Education (NACTE) to form a single system of vocational and technical awards. What is still not clear is the credit system. According to [23] in Tanzania, credits are sued to reward the incremental progress of learners, facilitating student transfer, recognizing prior learning and contributing of the definition TZQF qualification standards. Absence of the Tanzania Qualification Authority is also one of the barriers toward recognition of prior learning. § Awareness of the RPL programme is not well established;- The study revealed that; 84% of the were affected by the lack of awareness on the RPL programme, due to the mode of advertisement used. In most cases, the RPL programme advertisement are made through VETA website, fliers, newspapers such as The Citizen2, etc. This means of advertisement, as the way to create awareness is not friendly to informal construction workers, since their perception is dominated by job seeking ideology, and not skills learning, as well as certification issues. Thus, they spend little/no time browsing on education/vocational training websites, or reading educational issue on newspapers, although some of the respondents, revealed that; they have heard about the programme regardless of the means of advertisement, but they do not know if the programme intends to give them the formal education through the skills qualification framework set by the government under vocation an technical education where for those workers who do not have any formal education background have been given a chance of prior assessment, and if these workers seem to qualify, their skills are recognized through RPL certification. These RPL certificates give the workers eligibility for them to acquire the certificates of competence under VETA, where the competency certificates are awarded under three levels, and the level III is the highest level of education under VETA. If a person has been successfully awarded the level 3 certificate of competence (NQF level 4), he/she is considered the same as a person with a form 4 certificate of ordinary secondary education, which is a minimum entry requirement for Basic Technician Certificate or Technician level 1, which may even leads them to Doctorate Degree or level 10 of education. In accordance with the NQF final draft of March 2010, and UQF of August 2012, and Quality Assurance Internal Guidelines & Minimum Standards for Provision of University education in Tanzania, Second Edition of June 2014, the two lower levels are basic vocational certificates (level 2) i.e. NQF level 3 and VET level 1 (i.e. NQF level 2). § Lack of adequate VETA centres in rural areas where there are many informal construction workers than formal workers;- 91% of the respondents, reported on that; the programme is under VETA and other authorized vocational institutions like DONBOSCO, and these vocational centers are few compared to demand of people, which is in line with [29]. Thus, some informal workers wishing to be recognized, do fail to achieve their target, due to the either; absence of these vocational institutions in their locality, or being located far away from their home/job place, hence becoming time-consuming and expensive for them to go for RPL registration and recognition processes. § Non-realization of benefits Skills Development Levy (SDL);- Various charge SDL which is collect by a Tax Authority (TRA for Tanzania) under the Vocational Education Act and Income Tax Act. The aim of this levy is to increase investment in education and training for the workforce. Various Skill Development Levies Acts revealed that; the levy grant scheme initiative intends to encourage a planned and structured approach to learning and to increase employment prospects to job seekers. The levy rate differs from country to country. In Tanzania, the rate applicable of SDL is 4.5%, of total emoluments paid to employees monthly, [28]. Mutual benefits between employers/contractors and VETA on the use of SDL will increase morale for collaborations toward recognition of RPL to informal construction workers. As pointed in previous section 2.9, the authors made effort to review previous barriers in various parts of the world as summarized in Table 2.4. A number of additional barriers have been noted as summarise in Table 4.2. Barriers that reappeared to be common included; lack of innovative methods for assessment criteria, such as portfolio of evidence, poor collaboration between various stakeholders (employers and workers in the design and implementation process). Others include time and cost constrains in the overall RPL programme which should have been bearable, as it is subsidized by the SDL. Other barriers were revealed to be the current challenges especially those ranked 1 to 4, and considered to be critical affecting the RPL programme.

|

5. Conclusions & Recommendations

5.1. Conclusion

- The study concludes basing on specific objectives, that; the awareness of the RPL programme being not well established; qualification standards (class standards) set, not matching with the occupational standards (field standards) acquired by workers; process being complex, with insufficient time and expenses during gathering evidences required for competence proof as a pre-requisite for joining the RPL programme; perception; RPL programme being not well established as well as lack of VETA centres in rural areas; and minimum age requirement being too high, continues to be the barriers on the recognition of informal construction workers through RPL programme.

5.2. Recommendations

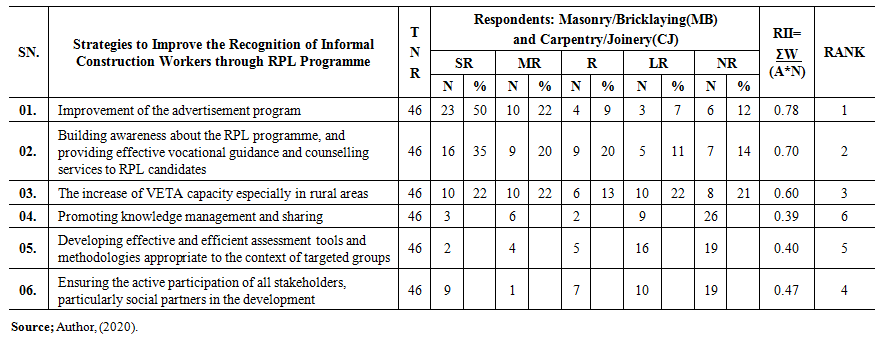

- Basing on the conclusion drawn, the study recommends basing on the strategies proposed to improve the recognition of informal construction workers under the RPL programme as seen in Table 5.1.

| Table 5.1. Strategies to be taken to improve the recognition of the informal workers under the RPL programme |

Notes

- 1. www.veta.go.tz. (accessed on Thursday, January 23, 2020).2. on Friday, May 22,2015, they reported on RPL programme initiation process; on Tuesday February 02,2016 they reported on the development of guidelines and RPL plan; and on 2017, they reported on the workers who succeeded under the RPL programme and were certified. 3. “Vijiwe” or “Magenge”; - are spots or a specified areas within a community in an urban or rural centre, where of most informal construction workers spend their time daily, waiting for any paying construction day work, e.g. masonry, carperntry, welding, paiting, earthworks, concrete works, etc.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML