-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2020; 9(1): 20-32

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20200901.03

Towards Sustainable Use of Existing Knowledge to Control Risks in Ethiopian Construction Industry – An Overview

Bezawork Beljige Bitane1, Bantayehu Uba Uge2

1Yohannes Haile Construction PLC, Ethiopia

2Hawassa University, Hawassa University

Correspondence to: Bezawork Beljige Bitane, Yohannes Haile Construction PLC, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Utilizing previous lessons gained from past construction activities shall not be the task limited to project managers alone. Engineers involved in a certain project from the conception to implementation shall be well aware of similar projects performed in the same context. Literature indicates consistent appearance of akin factors causing cost overruns and schedule delays attributed to the complex nature of construction industry even if every project experiences different challenges. The Ethiopian construction industry is just a subset of the broad global engineering projects where stakeholders are required to enhance construction project performance through conceptualized experiential reusable knowledge in a sustainable manner. In the framework of reusable knowledge management, the Ethiopian construction industry is not observed to fully transpire organized lesson learned collection methods and the obtained knowledge sharing approach. Not applying existing knowledge in new or progressing constructions has both time and cost implications. Therefore, systematic way of knowledge flow and experience sharing both at individual and company level has to grow well in order to offer ameliorated guiding principles to manage construction risks without repeating past mistakes. This work by itself will ignite initiation at least towards in-house proper documentation and utilization of prior experiences within construction companies and/or at large to nationwide accessible database (with appropriate security level) of socio-technical interactions among stakeholders.

Keywords: Risk control, Existing knowledge, Construction industry, Project management

Cite this paper: Bezawork Beljige Bitane, Bantayehu Uba Uge, Towards Sustainable Use of Existing Knowledge to Control Risks in Ethiopian Construction Industry – An Overview, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 9 No. 1, 2020, pp. 20-32. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20200901.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Civil engineers are entrusted globally in making the future to bring aspirational sustainable green environment by enhancing the quality of life that calls for preparing the coming engineers through training and early practice, i.e. “attainment of a body of knowledge (BOK) for entry into the practice of civil engineering at the professional level” [1,2]. This sustainability may require the civil engineering practice to align with the increasing advancement to technology as well as the design and construction problems’ complexity spurred by the burgeoning urbanization and industrialization [3]. Moreover, among the challenges encountered in reality is lack of ability to predict accurately uncertainties arising from available data based information, which in turn brings associated risks – be it accident risk, causality, business risk and reward or whatever [4,5]. The mettle for risk assessment and management demands continual improvement in existing risk control approaches and tactics to reduce and/or eliminate both project-specific and enterprise-wide emerging incidents. No signal has been seen on the possibility for future reduction in paying attention to risks [6] rather a tremendous need for appropriate information for reliability-based credible risk analysis pertinent to knowledge based decision making. The importance of previous lessons gained has been well recognized globally by many construction organizations through a lesson learned program (LLP) [7–9]. Critics on contractors’ performance to failure in achieving the lower clients’ satisfaction level in cost, quality, and time can be minimized by selecting a suitable construction method that would eliminate the possible negative consequences for the project [10]. For timely delivery of construction projects, implicitly all involved stakeholders must participate in collaboration with one another [11]. Effective management of knowledge with proper transferring channel from one project to the other capacitates the stakeholders whom may be disbanded and might not be gathered as a group after completion of the specified project [12]. This unique characteristic of construction projects makes the industry to be highly risky and complex [13]. In the race towards sustainable development, assessing the sustainability of the construction industry is worthwhile deserving prestigious attention [14,15]. Knowledge and absence of effective communication are reported to be among the main contributors for construction delay [16]. It is also indicated that “knowledge based advisory system” has great contribution in deciding appropriate procurement method by offering suggestions to control variables related to non-procurement [17]. The way of knowledge dissemination, people’s interaction and learning affects the performance of the project. It increases the technical breadth of the teamwork [18]. The positive or negative attributes to the project success or failure might be repeatable. A reusable knowledge with rich communication will significantly reduce the deficit through experiential learning interrelated human capital either individually or company level since no reported project exists in literature to have been completed without rework [19,20]. Eldukair and Ayyub [21] studied construction and structural failures resulted from variations in normal construction practices rather than the consequences from solely natural phenomenon during the period 1975-1986. They suggested regularity in techniques for assessing safety and construction operation evaluation after finding out the main reason for failures was limited control and integration of resources as manifested by inadequate technical communication and shortages in evaluation procedure during the stage of construction. Similar finding was early reported by Hadipriono and Wang [22]. Extending the same effort, Wardhana and Hadipriono [23] considered the record from 1989-2000 to investigate building failures in the United States. Among the reported construction deficiencies about built facilities’ failure exists unsuitable repair method and poor workmanship. In the Netherlands, while studying reasons of failure costs for claims on 50 deep excavation projects executed from 1995-2012, Korff and Tol [24] have found about 60% preventable failure resulted from the absence of regular lessons among projects while somewhere the necessary knowledge being available. They argued the possibility of preventing about 87% of failure by a risk management process deploying technical knowledge highlighting the unlikely repetition of identical mistakes by the same person flaws who might have been involved in more than one of the considered projects. Extending the same, Korff [25] indicated cost overruns and schedule delay due to flaws in accessing and utilizing existing information and knowledge; stating learning as a mind-set apart from partaking existing factual methods. Organizational memories from recorded information on circumstances, causes, and potential relations to failure events can be used to suggest knowledge driven risk management to evolving construction risks [26]. Ortega [27] encourages failure investigation with strong argument on the capability with the outcomes of the investigations to direct the gap in the current theory or practice so that an effective prevention mechanism could be forwarded for similar cases. An interesting observation can be noted from the case study made on bridge projects by Sibly et al. [28] where failure reappearance occurred in a long period of time such as 40 years. Many authors also discussed about the lessons from construction failures [20,29–31]. Even if knowledge and experience sharing in project-based organizations (predominant characteristics of the construction sector) is not a new topic, an increasing interest still exists towards knowledge governance in project environment [32,33]. The reflection made on the knowledge acquired as a data in one situation can be used as a knowledge to put into practice in different scenario. Proper evaluation of the learning process through which knowledge is shared plays an important role in avoiding the threat of knowledge loss. Structured documentation about the experiences from the project in terms of the flaws, problem encountered and decisions made contributes to a rapid knowledge based decision-making to future projects having comparable characteristics. Informal learnings through project internal meetings and/or external formal evaluations brings exchange of experiences with personal interactions for an optimal project performance. Such studies will minimize the blind use of specific code of practice mostly dictating but lacking clarification (off course being mindful about the fact that cods are revised); and suggest the need for detail knowledge apart from reporting failure causes. A need also arises to capture the possibly diminishing experiential lessons in people’s “mind” from being lost as the project managers resign the company [34]. Meaning, a systematic retrieval approach for active intellectual asset management for both successful and failure experiences shall be created for organizational competitive advantage embracing the continual developments in the industry. As the level of professional knowledge, skill and work methodology are often considered dependent on country’s development, the present potential problems experienced by developed countries are unlikely to be similar to those in developing countries [35–37]. As time goes, the demand to relief the need for housing and transportation due to unprecedented boom in urbanization will call the current developing countries to adopt infrastructure construction projects at least to some extent similar to those experienced by the developed ones. Even though construction projects are well known to be unique in nature so unable to just “copy-paste”, similar risk features could appear and the knowledge gained from previous information could be utilized to projects at hand. If, for example, an essential deep excavation project is to be executed in one of Ethiopia’s metropolitan, the lessons from the experience of the 50 deep exaction projects in Amsterdam reported by Korff [25] and Korff and Tol [24] may be adopted to avoid the recurrence of similar problems. Therefore, the Ethiopian construction can be taken as a tiny part of the world’s knowledge full construction industry to adopt previous experience in addition to the lesson from its own. Like the projects in developed countries, no matter how good the project is planned, risk will normally arise in Ethiopian construction as well. Consequently, risk assessment, control and management from stakeholder’s perspective has still been the focus of research in construction technology and management studies as about 40-60% of the country’s construction projects bore the risk of schedule delay and many cost overruns [38–42]. Those studies identified various risk events and risk allocation norms attributed to the poor performance of construction projects in Ethiopia’s context among which is reluctance in bringing past lessons into play in project performance evaluation. However, very little attention is given to the organizations’ practice in capturing both good and failure organizational tacit and explicit past knowledge, information germane to encoding in databases and transferring the lessons learned to following projects as well as the barriers to do so. This paper aims to elevate the very low concern in Ethiopian construction industry in this regard since knowledge is a vital asset. The authors gained the initiation after termination of the public building construction due to excessive addition and omissions in which they have been involved at project level from the contractor side. The project lagged almost more than 50% design construction period but extension of time for the contractor was easily granted due to the sufficiency of the reasons to claim such as consultant’s belated response to contractor’s request, frequent variation orders affecting the master schedule and delays in interim payment settlement, to mention some. The second author being the project manager had ordered the other to document the lesson gained on the project as “knowledge-as-practice” to be the baseline for the company’s internal structured knowledge transferring platform to save the time consuming generation of such kind of knowledge anew for use in concurrent as well as future projects. The contractor has a good experience in collecting and properly file internal and external correspondences, work orders, work progress approval certificates, and progress reports from mobilization until project handover, however, a matured practice to a clear knowledge data management was not apparent. Caldas et al. [8] express such collections as a simple “best-kept secrets” unless the lesson learned is implemented. Therefore, it demands enhancement through intensified post-project reviews in the same direction to escalate effectiveness and innovation by experience reuse. The perspective forwarded in this paper, however, has been tried to be made not limited to contractor’s side alone.

2. Construction Performance Control

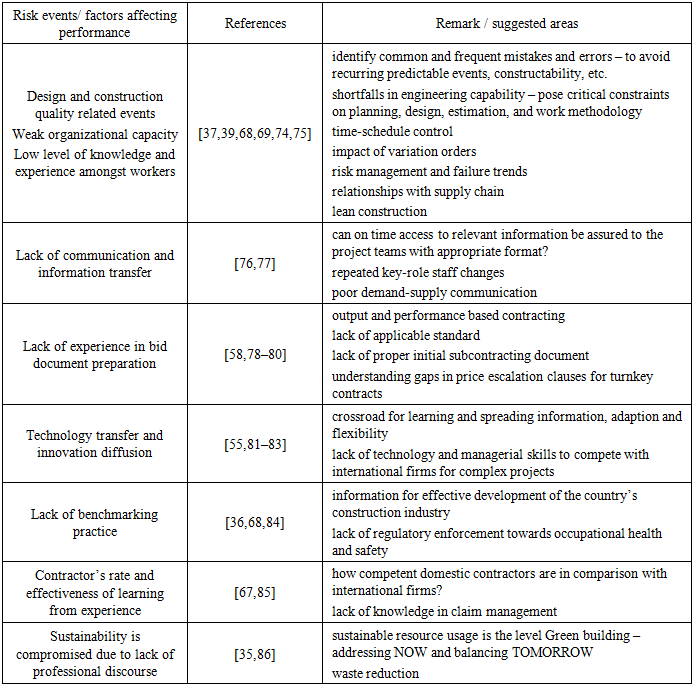

- The success of a given construction project can be assessed by its completion on time under the stipulated budget meeting the client’s level of satisfaction. Nonetheless, due to involvement of many stakeholders such as the client, the engineer, the consultant, the contractor, the supplier, the end-user, and the community, its performance is highly affected [43,44]. The construction company’s ability to understand its current performance influences how competitively it will sustain in the future. Be it inadequate scheduling or mismanagement, staffing, delays not attributed to Contractor’s fault, and/or any other concurrent delays happened either by internal causes (by the project entities) or external causes (by the government, material supply chain, or climate) have to be properly identified and minimized for successful completion of the project within prescribed cost [11]. Performance measurement is, therefore, important at various levels of the project, nevertheless, the traditional looking at time and cost performance alone is not enough [45]. Nassar [45] proposed performance indices in terms of time, cost, cash flow, safety, quality, profitability, team satisfaction, and client satisfaction. Examples could be avoiding continuous rework [46]. An attempt to improve safety performance can be made by knowledgeable company safety representative who is able to identify significant event factors and develop strategies [47]. Inadequate communication has been found the main supply chain risk factor in construction industry [48]. Currently, the Building Information Modelling (BIM) approach has got great popularity in global construction industry owing to its simulation capability in visualized progress information sharing [49–51]. Nonetheless, the use of BIM in Ethiopia is not mature [52–55]. The Ethiopian construction projects are often accused of poor performance being challenged by time, cost and risk management [38,56]. The government expressed by its Ministry of Urban Development and Construction (MUDC) has pointed out performance constraints attributed to these poor performances among which are inadequate experience of local contractors and erratic work opportunities favouring foreign companies in projects funded by donors [57]. Either management performance levels or operational performance levels could be set to achieve a specific level of performance indicator or service outputs. An attempt for implementation of output performance based road contracting (OPRC) by the Ethiopian Roads Authority (ERA) on some maintenance and improvement projects outsourced to state owned construction companies has been found to face many problems among which is lack of experience and knowledge on OPRC that resulted in ambiguities in contract document [58]. Sinesilassie et al. [59] showed that project manager’s lack of knowledge has undesirable influence on cost performance. Even though it is considered indistinct and unreliable, future performances can be predicted from observed performance [5]. To suggest future act in such situation, reflective skill of professional participants is important to fill the gap by making adjustments so that things are done right. Professional reflections on project evaluations made at its progress or end can interestingly be linked to organizational learning process as expressed by “reflection-on/in-action” [60]. A reflection that is more useful incorporates enablers and barriers of lesson sharing, experienced mistakes and remedial measures implemented along the project period. In this regard, professionals’ exercise of engineering judgment in construction projects is essentially communicated to various stakeholders and hence offer some elixir to foresee consequences [61–63]. It is to be noted and acknowledged in knowledge transfer that background career brings different areas and level of competence in individual project members that gradually improves with experience. Continual assessment of employee’s knowledge according to the need and project requirement to spot skill shortfalls and deliver essential information to fill the gap promotes the project productivity through expertise teamwork – as a cooperative colleagues instead of subordinates [64]. For space brevity, only some selected risk events affecting construction performance in Ethiopia attributed to experiential knowledge are listed in Table 1.

|

3. Lesson from Own Challenges

- As the amount of projects being managed by a company increases, the value of stored knowledge and dissemination of knowledge from preceding to following projects becomes higher to deal with optimization of the growing intricacy of project work under time pressure [34]. Contractors usually want to win many bids and have multiple projects yet facing difficulty in completing the project in the allocated time and cost [65]. The construction industry is found to be engaged in moneymaking rather than sustainability [35]. The same is reported in Nigerian construction industry characterized by employing inexperienced supervisors to escape high professional’s salary compromising the quality of work [66]. In the lesson gained from problem assessment made by ERA, the local contractor’s capacity and competency has significantly contributed to the poor performance. Regarding project delivery system, the experience of the authority is bringing preference to Design-Build approach instead of the former inclination towards Design-Bid-Build system [56]. The discussion of Zawdie and Langford [67] on the lessons to learn from community infrastructure development highlighted the importance of narrowing the mismatch between provision and need. Mengistu and Mahesh [68] indicated poor project performance depends on organizations’ capacity; and poor knowledge and risk management was among the top improvement dimension sat. Yadeta [69] showed augmentation of variation orders on public projects affects the construction progress and brings project cost increment. Shiferaw Belachew [70] and Zinabu Tebeje [71] reported Ethiopian construction is mainly suffering cost overruns from the level of project time control technique followed by price escalation. Henok Asfaw [72] argues managing construction projects from the perspective of any of the tripartite project entities (stockholders such as the owner, consultant, and contractor) to be different and with his other book [73] tries to technically equip fresh graduates to construction site practices in Ethiopian context.Even though sound research could not be found on human resource turnover rate, the Ethiopian construction industry faces fast turnover in skilled and non-skilled personnel. The people jump from one contractor to the other based on salary negotiation. Thus, the project will be started by some project manager and completed by the other without appropriate channel to handover among intermediate successors. Such kind of sudden project key-role playing staff changes has been reported to cause problems in project progress and planning process [37,87]. The same is observed in consultants’ side as the resident engineer frequently either resigns or works surprisingly intermittent leaving responsibility to assistant residents that result in lack of immediate response from the consultant to the contractor’s request. Late instruction given by the design and supervision group is among the factors that contribute to construction project delay [88]. Likewise, even though the contract document mandates the consultant and the contractor to deploy safety engineer, reluctance is seen to some extent on some projects in enforcing the continuity of the said staff throughout the project life. The face-to-face interaction of key personnel towards quick and informative performance reviews and early feedbacks usually reduces the consequence of cost and time implications from the beginning when the undesirable performance situation appears manifesting itself. Thus, the client could have carefully observed both the consultants’ and the contractors’ staff deployed onsite on a regular bases if the history of main staff overturn rate on delay and associated risk could have progressively been accessible. The apparent attitude towards “commercial privacy is significant than circulating the truth”, however, is cloaking the truth under permissible constraints [89]. In addition, it is reported that contracts create an interface between organizations and individuals contributing as the root source of failure. The extent of retaining and attracting experienced project managers and skilled professionals could either improve or be an obstacle to the efficiency of the company, however, limitation on research findings in this direction led the authors to abstain from forwarding sound inferences. Interested one may follow the work of Kale and Arditi [90] and Mofokeng [91] to address the issue how progressively it can be reflected on failing construction companies in parallel with organizational lack of lesson learning and professional cooperation. Another interesting lesson to adopt is the “Observational Method” mostly practiced in geotechnical engineering because of the associated multiple uncertainties in the field. The observational method is being successfully used to manage construction risks by incorporating new knowledge as the construction progresses since Peck [92] formally introduced Terzaghi’s “Learn-As-You-Go method” [63,93]. Even though proven to its ability to permit both economy and safety more specifically in deep excavation projects in urban dwellings, observational method is not recommended if the designer not plans prior countermeasures for disclosed unfavourable phenomenon [92,94,95]. In a developing country like Ethiopia, the approach could also be implemented broadly to the extent of attracting smoothly the young talented digital native succession engineers with mentorship strategy to equip them to be well-experienced expertise for the future construction industry. By doing so as the construction advances, it goes creating smooth leadership transition between the so-called “baby boomers” – those soon going to be retired and the rising younger generation – the “millennial” construction professionals. Limited report on development of accessible (to some extent based on the security level choice) and digitalized national statistical database system exists for construction-related accidents to assist risk analysers to be able to update the frequentist probability and/or judgmental information. Availability of such data system brings forth research outcomes highlighting areas of special consideration like the assessment done by Dong [96] based on the US datasets that showed younger immigrant construction workers to be more prone to high-risk activities and their death rate being higher than the native. Moreover, online comprehensive failure information made available by concerned stakeholder (at least for in-house organizational level) will enable the knowledge grasped to be retained instead of evaporating as their senior engineers retire. The same is suggested to integrate failure lessons (be it structural failure, material defect, construction and design error, failure to meet budget, or any other performance problems) as professional capacity development both in academic curricula and practice for graduate engineers; since failure information normally leads the research aiding design improvement for evolution of the current success in good engineering practice [89,97,98]. A remarkable move in this direction could be the introduction of labour-based technology into curricula by the Addis Ababa University in collaboration with ILO [99]. Similar recommendation was forwarded by some authors to underpin the contribution of academic and research institutions’ active participation [24,100]. Public and private training institutions specialized in construction risk assessment through collecting claim cases from legal dispute resolutions can be encouraged to prepare more refined database to offer practical training upon request by companies under need. Another way of contribution to the delivery of ideas to construction industry is establishing civil engineering specific public libraries akin to the recent “Ethiopian Construction Centre of Excellence library” in the capital Addis Ababa that has been found helpful to postgraduate civil engineering students in doing their research. The government has assisted the initiators by providing space to the library. Tendency to expect unrealistically much relative to the supplied resources (human, material, equipment, and others) by headquarters from the project team is the other observed common feature [72]. Albeit the project team reminds repeatedly for the supply of requests from headquarters until the resources are delivered, there still exists the need to crosscheck operational efficiency and the performance of the project to avoid the slow progress – the problem often considered as common in projects managed from the top [37]. Expected barriers and/or challenges in implementing knowledge management process, but not limited to them: • perception to consider documenting failure cases as a reflection of poor project management resulting in managers’ loss of interest to share it • competition among project managers of concurrent projects for project-level performance measurement matrices – some companies may collect data but don’t share it with competitors • lack of organizational culture for lesson learned and willingness to disseminate • time constraint to devote to lesson learnt under the pressure from project schedule • lack of interoperable technologies to improve use of best practice electronically to assess competitive positions and minimize rework• lack of practice for research oriented prioritization towards potential improvement of company’s efficiency and coordination for productivity • inclination to workforce employment rather than retaining experienced human resources • immature habit of submitting early notice of intent of future claim attributed to lack of knowledge of contractual right• contractors inclination to focus only on time extension claims yet not issuing financial claims• developing strong linkage between research infrastructures and the construction industry

4. Lesson from Foreign Construction Companies

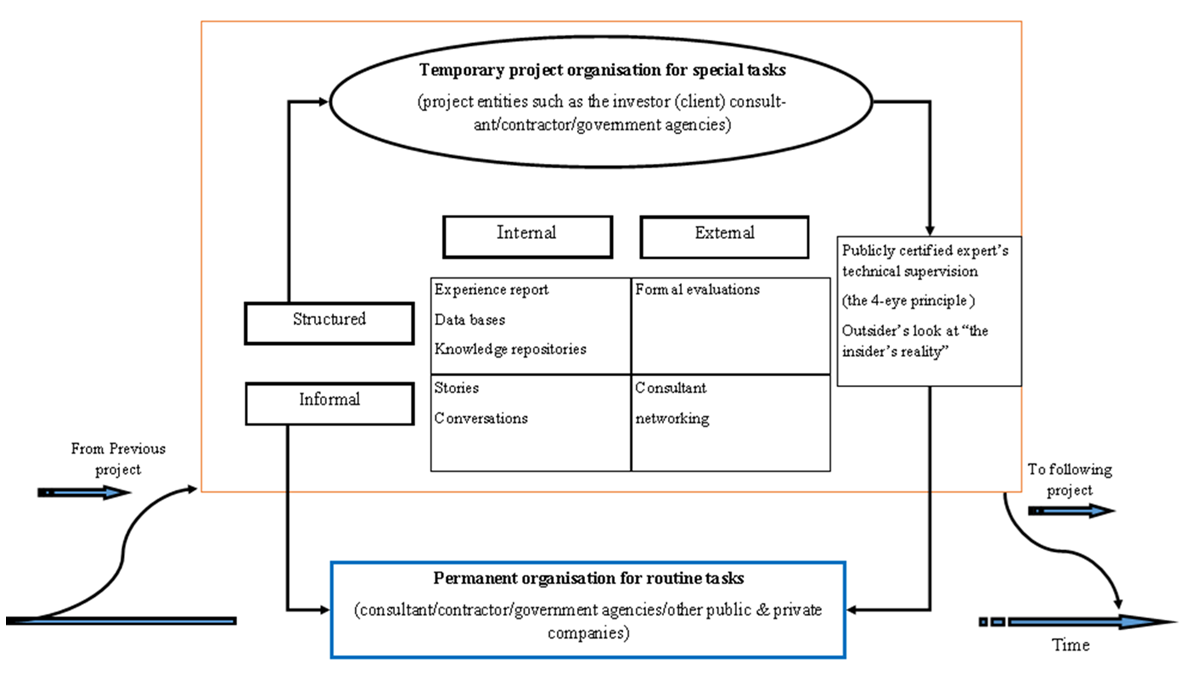

- The Ethiopian construction has become a huge international construction business opportunity owning to the country’s rapid economic growth to revivify massive infrastructure development attracting foreign entrepreneurs to participate from conducting feasibility studies to undertaking specific construction work. The industry has been seen to consume enormous imported construction material and machineries pertinent to extensive construction projects [101]. Special support has also been given to foreign companies inaugurating large-scale projects. Internationalization of construction projects obviously widens the competitive advantage nevertheless many international construction firms working in developing countries have been seen "to hide behind a political association" and not to prefer joint venturing with local firms regardless of the national government insistence [102].There are many foreign construction companies in the country such as the Chinese and western firms involved in major construction projects offered through competitive international bidding. An example of commercial construction projects underway with the Chinese company “China State Construction and Engineering Corporation Ltd” is the inspiring East Africa’s tallest high-rise building owned by the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia in the country’s capital city – Addis Ababa and is expected to have a height of 198 meters upon completion [103]. The Chinese companies also hold significant road, bridge, stadium and railway construction projects [77,104]. Italian contractors such as Salini Costruttori are involved in hydropower projects like Gilgel Gibe II, Gilgel Gibe III, Tana Beles and the Africa’s largest Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) [105]. Other companies such Techniplan International Consulting (Italy), UNIMPRESA PLC (Italy), Elmi Olindo Construction (Italy), The Solel Boneh Planning and Consulting Co. (Israel), IL&FS Transportation Networks Limited (Indian), Elsamex S.A ILFS (Spain/India), Keangnam Enterprises Ltd. (South Korea), The Arab Contractors (Egypt) are the few among the foreign companies, just to mention.Having many such global construction companies in the country through international tendering creates a good knowledge and technology-sharing hub to reap a benefit for lesson learnt practice from their experience in different cross-cultural and supply chain background. More variety on design and construction from the experience of different countries can be caught. Apart from this, creating conducive environment and convenient knowledge transfer channel is required for the successful technology and lesson leaned transfer from foreign companies. Meanwhile, as the technical competitiveness (capabilities and skills gained through dynamic technology transferor-transferee relationship) gets developing by leaning and close assistance from international joint ventures, dependency on foreign construction companies in design and construction of essential infrastructure projects will gradually be moderated. This brings emergence of internationally competent construction companies, to be discussed in detail later. To learn from the experience of the expatriates, one alternative is development of co-operative strategic learning environment through international joint ventures to acquire knowledge resources for company’s efficiency via a process of “learning by doing” [106]. We do suggest the concept of learning to co-operate instead of “learning the other partner’s skills” for attaining understanding of the process while developing competencies of domestic companies, i.e. a competitive strategy in collaborative network [7]. At this point, there may be a need to set standardized obligatory requirements and forcing its implementation to assure technology transfer through subcontracting to local firms and allowing domestic professional to participate on projects. Yet, observations still show existence of conflict of interest between the local companies and the ever-increasing cost down by the Chinese in bidding process drawing the perception that the major contracts are given to Chinese because of the economic and technical aid from the Chinese government. The authors suggest the knowledge exploration and dissemination approaches depicted in Figure 1 for the companies to learn lessons from either in-house project experiences or international joint ventures.

| Figure 1. Knowledge exploration and dissemination approaches between parent organization and projects (modified after [12,33,34,107]) |

5. Construction Industry Development

- Unsatisfactory progress in construction work performance with respect to cost overrun and schedule delay has been reported in Ethiopia’s building construction demanding for improvement in construction management practice [38,68,75,108,109]. Among the four improvement dimensions forwarded by Mengistu and Mahesha [68], the second priority area is the use of performance experiential lessons through knowledge dissemination improving lesson learned management. The first improvement dimension being Project management following by Knowledge and risk management, Project development and contract management, and Organization management respectively. The headache from time and cost overrun thus can be minimized with implementation of proper project management process [110].The number of private domestic construction companies joining the fastest growing construction industry of the country is escalating [75]. Moreover, the housing development program created opportunity for building enterprises to emerge in small and medium scale [38,111]. With initial technical (training on design guides, professional development) and financial (assistance by supplying credit terms, project offers) support, the government office responsible for development of these small and medium scale enterprises gives recognition so that they get into project works such as condominium construction in different cities. Similarly, the government has established a capacity-building program in the road sector through the Ethiopian Roads Authority. The Universal Rural Road Access Program (URRAP) launched in 2011 by ERA to construct all-weather low volume gravel-surfaced roads is one its kind in creating employment opportunities throughout the country by providing a comprehensive labour-based technology training to local entrepreneur consultants and contractors. Apart from ensuring ease of rural access and connectivity to fuel up to the contribution of road network development, this program is acclaimed for its potential for intensive employment generation in poverty reduction by consuming huge amount of unskilled labour transformed soon technically [99,112–115]. Although the availability of ample human resources in the industry is leading construction enterprises to prefer practices of casual recruits, much attention shall be given to the development of human resource for the industry to operate efficiently regardless of the low labour costs. The government has also plans to promote the small-scale URRAP consultants and contractors to middle class enterprises by offering maintenance and rehabilitation projects of gravel roads that are mostly done by the on-force branch of the Ethiopian Roads Authority regional districts. Such promotions by creating access to projects through policies in favour of small construction firms has been a consensus among many domestic construction capacity development strategist [116]. When planning training to provide technical assistance for performance improvement and company growth, it is required to consider the level of contractors and consultants to avoid participants’ perception of the training as a mare orientation program [111]. Moreover, developing the capacity of local contractors to meet the unprecedented infrastructure demand will cut the foreign currency the country demands to spend in international bidding for bringing foreign construction companies. The substantial reliance on imported construction materials added on transaction costs from hiring foreign companies puts pressure on the country’s available hard currency that needs to be reduced by minimizing the contribution from either of the two. In addition to that, the study on claim management by Abdissa [85] shows foreign companies mostly end up claiming more than the projects’ total cost. Obviously, it could not be an overnight activity rather requires a couple of time to effect new knowledge and reforms to support the construction industry development to fill the domestic companies’ technical and financial capability gap to limit the immersion of international firms in local construction market. The other knowledge gap appears in the quest for construction industry sustainability in delivering sustainable development embracing holistic construction and administration of the assets to the satisfaction level of stakeholders, which is the challenge seen even in the developed world [117]. Researchers mentioned that the capacity and skill level of the local construction industry influences the link between project management and sustainable human development [118]. In this regard, even though Ethiopia has officially launched construction industry transformation counsel in 2017 to tackle major challenges disturbing the sector’s sustainable development, the overall performance of the construction industry is still confronting problems arising from the weak capacity and lack of professionalism among consultants and contractors [36]. Experience has shown that the country is adopting the Japanese Kaizen philosophy to reduce project costs by implementing efficient construction project management system tools [101,119]. This provides a means to easily locate materials, tools and equipment, avoid over-crowdedness of work area, and improves the quality by considerably cutting waste in terms of resources and more importantly time. For heavily interdependent project team members, team-based rather than individual reward and recognition can support the project team performance management, since reward strategy is one of the success factors in knowledge management process [64,68]. Promote international partnerships and networking both through individual professionals studied abroad and joint ventures. Human resource development can also be facilitated through strong university-industry linkage building research progress in technical and scientific technology transfer to generate and apply knowledge [120]. The involvement of the Chinese and Korean construction firms in international practice, for instance, has grown by both capacity developed through partners to learn and use the acquired knowledge along with company’s reputation enhanced from collaboration and the lesson from the intensive research [121,122]. It is to be boldly mentioned that the previous domestic contractor’s capacity development program has successfully produced some internationally competitive companies such as Flintstone Engineering running projects overseas (Tanzania). Other Ethiopian construction companies that are working abroad in different African countries include Ethiopian Construction Works Corporation, Alemayehu Ketema, Tekleberhan Ambaye, Beza Consulting Engineers and SABA Engineering, just to mention few of them to show how the industry is also trading to be competent in overseas work.

6. Conclusions

- The Ethiopian construction industry is burgeoning at a terrific pace with expertise contribution from international companies and the country’s dedication towards comprehensive sustainable construction industry development. Through the long way to this stage, the industry has gotten multiple success and failure lessons. So has been in each domestic companies, even though the performance of the construction industry is still poor. The knowledge acquired through experience germane to capacity building in every construction company as well as the companies’ experience from different projects can be used to reap practical lesson beneficial to apply in future project trends. However, the trend in utilizing previous knowledge is not mature and/or even not been the habit in some construction companies. Knowing how to use information from previous project files and post project evaluations as a stepping-stone to fill existing gaps has to gain attention for future company’s competitiveness. The review indicates that some potential risk events could have been minimized if successful exploitation of previous knowledge had been implemented during project execution. An internal structured reporting on experience gained from each project is sought as a lesson-learning tool, not the mere project completion report. Conducting further investigative surveys on the socio-technical interactions taking place during knowledge generation, codification and dissemination is suggested to deliver strategic lessons learnt management to bridge gaps in risk control practice.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML