-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

p-ISSN: 2326-1080 e-ISSN: 2326-1102

2019; 8(4): 122-126

doi:10.5923/j.ijcem.20190804.03

Road to For-profit: Observation from the Case of a Believer-centered Chinese Folk Temple Reformation Project

Kuo-Yan Wang

Guangdong University of Petrochemical Technology, Maoming, Guangdong, China

Correspondence to: Kuo-Yan Wang, Guangdong University of Petrochemical Technology, Maoming, Guangdong, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The main objective in brand development is to strengthen equity by enhancing the satisfaction of customers. This study presents the bold assumption that in a folk temple in Taiwan, the committee members are actively engaged in brand development through the nurturing of loyalty among followers. This empirical research revealed that a service decoration project in the temple was aimed at increasing funds obtained through donations. The provision of activities (lighting butter lamps, for example) is viewed as a cost saving measure and a means to streamline worship. This article also surveyed followers to reveal their perceptions of the temple decorations and ascertain the implications of integrating marketing concepts with the operations of a folklore temple.

Keywords: Chinese folklore temple, Lighting lamp, Brand development, Religious service

Cite this paper: Kuo-Yan Wang, Road to For-profit: Observation from the Case of a Believer-centered Chinese Folk Temple Reformation Project, International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management , Vol. 8 No. 4, 2019, pp. 122-126. doi: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20190804.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Religion is a growth industry (Kuzma et al. 2009) and religious organizations have long used modern marketing techniques to expand the number of followers in order to increase donations (Dobocan, 2015). As a result, previous articles have highlighted public views regarding advertising in churches (Newman and Benchener, 2008), the utilization of social media to manage the “brand” image of churches (Waters and Tindall, 2010), advertising with Islamic overtones (De Run et al. 2010), marketing strategies for religion-related peripheral products (McGraw et al, 2012), and the activities of religious organizations operating promotions via TV (Iyer et al. 2014) or social media (Wang, 2015a). Despite the differentiation orientation of organization operations between for-profit enterprise and non-profit religious organization, their objectives, however, can be shifted in much the same way: to increase revenue. These surveys tended to focus on the basic attitudes of respondents, while the details of how religious organizations create a profitable “business” are seldom discussed. The term “business” must be defined in order to more comprehensively present the marketing perspective of the major religions. So et al. (2017), Nam et al. (2011), Pappu and Quester (2006), and Jones and Suh (2000) claimed that a critical factor in the success of an enterprise is ensuring customer satisfaction. This case study investigated a project involving the decoration of services in a Chinese Taoist temple. These decorations were established on a profit-based view of working within cost, scope, and time constraints provided by project management (Hietajärvi and Kirsi, 2018; Sense and Fernando, 2011; Schwalbe, 2009; Williams 2005). Our work also examined the attitudes of followers toward the marketing approaches used to promote the added “product items” of the temple, and gives some managerial implications for the existing Chinese-style management discussion.This study is divided into four parts. First, the article briefly introduces the characteristics and functions of lamp lighting services in Chinese folklore temples as well as the emerging phenomenon of religious consumerism. Then examine questionnaire results obtained from followers of the folklore temple throughout the decoration project. Subsequently, investigate the implications of religious organizations engaging in marketing-oriented activities. Conclusions are drawn in the final section.

2. Lamp Lighting Service in Folklore Temples

- “Many seek illumination by lighting a lamp, but true light shines within our hearts.”

-Cheng YenBuddhist bhikkhuni, founder of Tzu Chi Foundation Unlike monotheism (Christianity, Islam and Judaism), folklore beliefs in Taiwan are syncretized and pantheistic (Chang et al. 2012; Chang, 2009), and have been an established part of Taiwanese society for over a thousand years. Temples were established to honor the Taoist deities and Buddha, such as the Jade Emperor, Imperial Sovereign Saint Kuan, Sea Goddess Mazu and Avalokiteśvara (adopted from Buddhism). Temples, churches, mosques, and synagogues, provide places for people to worship. However, the high degree homogeneity in folklore belief has led many temples to separate from community-based patterns to expand their follower base and donations by increasing the range of religious services. Wang (2015b) claimed that lamp lighting is the most common service provided by ordinary folklore temples in Taiwan. In all spiritual beliefs, it might be said that lighting a candle is derived from a yearning for light and inner peace. Wong (2011) mentioned that in Taoism, lamp lighting is usually performed at an altar in front of the patron deity of the temple or the deity being honored in the ceremony. The lamp lighting symbolizes the original spirit, which is the light of the Tao within. In Chinese folk belief, believer attitudes toward lamp lighting are based on “risk prevention” in an ever-changing world (DeBernardi, 2008). The follower enters a temple and registers lamp stands before Chinese New Year, with the aim of seeking a deity’s grace in the coming year. Crowds must even cue up for lamp lighting at many well-known Taoist temples, such as Long Shan Temple in Taipei (The Apple Daily, 2015; Figure 1). Figure 2 presents a light-emitting diode (LED) lamp located at a folklore temple, which has recently replaced traditional lamps.

-Cheng YenBuddhist bhikkhuni, founder of Tzu Chi Foundation Unlike monotheism (Christianity, Islam and Judaism), folklore beliefs in Taiwan are syncretized and pantheistic (Chang et al. 2012; Chang, 2009), and have been an established part of Taiwanese society for over a thousand years. Temples were established to honor the Taoist deities and Buddha, such as the Jade Emperor, Imperial Sovereign Saint Kuan, Sea Goddess Mazu and Avalokiteśvara (adopted from Buddhism). Temples, churches, mosques, and synagogues, provide places for people to worship. However, the high degree homogeneity in folklore belief has led many temples to separate from community-based patterns to expand their follower base and donations by increasing the range of religious services. Wang (2015b) claimed that lamp lighting is the most common service provided by ordinary folklore temples in Taiwan. In all spiritual beliefs, it might be said that lighting a candle is derived from a yearning for light and inner peace. Wong (2011) mentioned that in Taoism, lamp lighting is usually performed at an altar in front of the patron deity of the temple or the deity being honored in the ceremony. The lamp lighting symbolizes the original spirit, which is the light of the Tao within. In Chinese folk belief, believer attitudes toward lamp lighting are based on “risk prevention” in an ever-changing world (DeBernardi, 2008). The follower enters a temple and registers lamp stands before Chinese New Year, with the aim of seeking a deity’s grace in the coming year. Crowds must even cue up for lamp lighting at many well-known Taoist temples, such as Long Shan Temple in Taipei (The Apple Daily, 2015; Figure 1). Figure 2 presents a light-emitting diode (LED) lamp located at a folklore temple, which has recently replaced traditional lamps. | Figure 1. Crowds waiting in line to register for lamp lighting (The Apple Daily, 2015) |

| Figure 2. Lamp stands inside a Taoist temple in Taiwan (Photo retrieved from http://goo.gl/TQs4lz. Assessed 4 December 2015) |

3. “Enterprise” Folklore Temples-Increasing Secularization and/or Bringing Happiness?

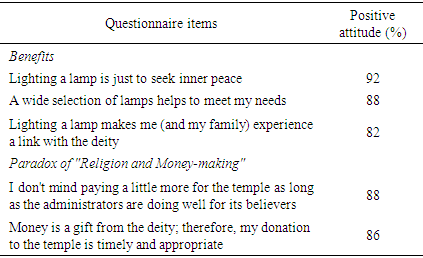

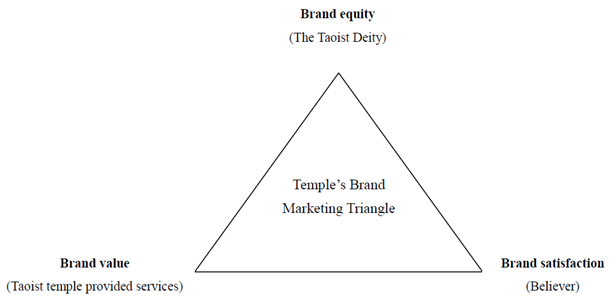

- Bourdieu (1998) proposed the notion of “religious enterprises”, claiming that the worshipped deity is being dedicated as a commodity in this kind of religious organization due to its characteristics of ritual and mystery. Since ancient times, Taoist priests and believers have provided rich offerings to gain blessings from their deities. Today, the trends ruling social interactions between priests and followers are reflected in simplified religious ceremonies, peripheral merchandise representing anthropomorphic deities, and popular religious publications (Wang, 2015b). Simultaneously, the operating environment of Taoist temples is gradually taking the form of a horizontal competition due to a high degree of homogeneity. Temples are switching from religious organizations to “brand” businesses. The number of religious rituals has been increasing to meet the demands of followers seeking the help of deities, particularly during the 2008 world economic crisis. Temple administrators are racking their brains to find ways to compete for profits, resulting in various new business practices. Argyle (2001) found that religion and beliefs play an important role in happiness, and Nam et al. (2011) found that brand equity and loyalty, which both are based on people’s subjective feelings, are the most important factors related to customer satisfaction. In accordance with these findings, this study proposes that Taoist deities are a temple’s brand equity, religious services are a reflection of brand value, and brand satisfaction can be determined according feelings of happiness as perceived by believers. This raises the question of whether the marketing of religious services will undermine a sense of spirituality or adversely affect the contentment of followers. To answer this question, this study aimed to ascertain the feelings of those frequenting a folk temple in Taiwan, and intends to express the followers’ attitude towards whether such profit-oriented project harmed the purity of characteristics of their beliefs.

4. Illustrative Example

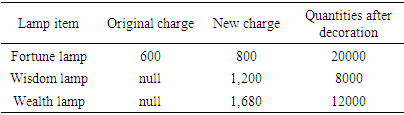

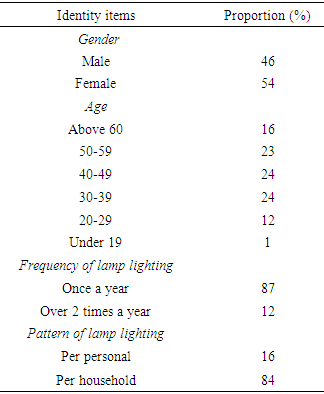

- Taoist temple M is located in an emerging city in northern Taiwan with over twelve thousand regular worshipers. It widely believed that worshipping the deities can be efficacious at providing peace, prosperity and stability for their people. In Taiwan, a popular deity is Mazu-the sea goddess in Taoism, Avalokiteśvara- a bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas, Lord Emperor Wenchang-the god in charge of success in examinations, as well as good fortune and reputation in literature, and Gods of wealth. For nearly two hundred years, temple M has been attracting believers from all walks of life; everyone from the general public to political figures visits the temple for worship. As a result, Temple M has long been a center of local religious beliefs. The new executive committee members of Temple M were officially instated on August 1, 2018. Following careful observation of the donation structure, the committee noted that the economic recession had not affected the amount of donations, citing the fact that the 40,000 lamp stands for ‘Fortune lamp lighting’ were nearly full. At present, the charge for Fortune lamp lighting is 600 New Taiwan Dollars (NTD; approximately 20.10 USD) for each lamp each year. Many other Taoist temples of similar size offer several kinds of lamps, such as Medicine Buddha lamps for good health, wisdom lamps for luck in study and examination, and wealth lamps to ensure smooth business transactions. In contrast, temple M provides only one type of lamp, a fact which may have been curtailing the profits raised by donations. To improve the current situation, the new management chose to include Wisdom and Wealth lamps in addition to the original Fortune lamp. They chose this course of action because all specific lamps have their own guardian, such as Lord Emperor Wenchang, who is associated with the wisdom lamp, and the Gods of wealth who protect the holders of Wealth lamps, both of which are worshipped at temple M. The annual charges for the new lamp lighting services are as follows: Fortune lamp (800 NTD; 26.7 USD), Wisdom lamp (1,200 NTD; 40.16 USD), and Wealth lamp (1,680 NTD; 56.23 USD). The decoration budget totaled 19,200,000 NTD (646,240 USD), paid by the temple organization (25%), donations (60%) and government grants (15%). Table 1 presents the updated lamp and service charges. At present, all of the lamps are fully booked, resulting in an estimated increase in donations of 45,760,000 NTD (1,523,400 USD), compared with the 24,000,000 NTD (801,190 USD) prior to these changes, which is largely the result of a 90.6% increase in donations.

|

|

|

5. Discussions

- Taoist-Buddhist based Chinese folklore temples are intermediaries connecting the deity with followers. However, from the perspective of marketing, the existence and historical development of a Taoist temple is usually limited by the scale of the community, because each community has its own temple. This makes it difficult to expand the “market size”. Thus, in this study, the Taoist deities were treated as a “developed equity” of the temple. Temples provide religious services with high degree of niche overlap, and the butter lamp ritual is no exception. The lamp stand decoration project at Temple M resulted in the cutting of operational expenses to increase profit margins. At the same time, updating the choice of lamp items increased revenues, so the temple could reduce its reliance on donations and public funds. Believers at this temple did not mind paying more for religious services, because to them, the most important thing is obtaining spiritual well-being for themselves and their loved ones. According to our observations, the relationship between the Taoist deity, the temple itself, and the believer is an equilateral triangle, which maintains brand equity, reveals brand value and customer satisfaction, and attains a win-win situation between the temple and its followers (Figure 3).

| Figure 3. Triangular marketing strategy for a belief center development |

6. Conclusions

- This study introduced a service decoration project in a Taoist temple and surveyed the perceptions of follower about profit-oriented operations. We also examined the reasons for follower perceptions as well as attitudes toward religious marketing. These results may prove valuable for Taoist temples considering the adoption of modern marketing techniques to strengthen revenues. These results also help to address the future research directions of religious services, particularly in East Asia.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML